Abstract

Background:

Spinal cord injury (SCI) can cause psychological consequences that negatively affect quality of life. It is increasingly recognized that factors such as resilience and social support may produce a buffering effect and are associated with improved health outcomes. However the influence of adult attachment style on an individual’s ability to utilize social support after SCI has not been examined.

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to examine relationships between adult romantic attachment perceived social support depression and resilience in individuals with SCI. In addition we evaluated potential mediating effects of social support and adult attachment on resilience and depression.

Methods:

Participants included 106 adults with SCI undergoing inpatient rehabilitation. Individuals completed measures of adult attachment (avoidance and anxiety) social support resilience and depression. Path analysis was performed to assess for presence of mediation effects.

Results:

When accounting for the smaller sample size support was found for the model (comparative fit index = .927 chi square = 7.86 P = .01 β = -0.25 standard error [SE] = -2.93 P < .05). The mediating effect of social support on the association between attachment avoidance and resilience was the only hypothesized mediating effect found to be significant (β = -0.25 SE = -2.93 P < .05).

Conclusion:

Results suggest that individuals with SCI with higher levels of attachment avoidance have lower perceived social support which relates to lower perceived resilience. Assessing attachment patterns during inpatient rehabilitation may allow therapists to intervene to provide greater support.

Keywords: adult attachment, depression, inpatient rehabilitation, resilience, social support, spinal cord injury

It is estimated that there are approximately 12,000 new spinal cord injury (SCI) cases per year, with approximately 270,000 persons living with SCI in the United States.1 Experiencing an SCI is a risk factor for physical (eg, pressure ulcers, neurogenic bowel) and psychological impairments,2 including anxiety3,4 and depression.5–8 Depression is the most common type of psychological distress experienced after SCI.9 Depression in persons with SCI has been associated with a variety of negative health outcomes including reduction in quality of life, less independence in activities of daily living (ADLs), increased frequency of pressure sores and urinary tract infections, greater medical expenses, and higher risk of suicide or requests for terminating life.7,9,10 It is important to investigate factors that influence an individual’s ability to successfully adapt after injury to better understand how to treat and prevent these negative health outcomes. Previous research has identified several variables critical to an individual’s ability to respond positively after an SCI, including resilience, social support, and absence of depression.11–16

Resilience has been defined as the “ability to maintain a stable equilibrium”17(p20) and “how an individual reacts and adapts to a traumatic event.”16(p9) Findings from the literature indicate that resilience is a trait-like quality,11,16,18 which is negatively associated with depression at different stages after injury,12,16,18 and has been linked to reduced psychological distress15 and greater quality of life, self-efficacy, and acceptance of injury.11,13,18

In reviews of the resilience literature, social support is identified as a protective construct,17,19–23 and different models exist to explain how social support is related to management of distress, including the buffer model (increased social support leads to a reduction in association between stressors and subsequent distress) and direct model (increased social support is related to increased well-being, regardless of whether a stressor is present). However, the literature generally supports an understanding that social support is not stagnant20; rather, social support often fluctuates in response to a specific stressor, depending on factors such as the degree of support resources (eg, family and friend support) and personal factors (eg, social skills) that either enhance or impede support from others. Attachment theory is well suited to examine the dynamic process of these personal interactions after an SCI, with its emphasis on developmental relationships and the individual’s ability to regulate emotions and cognition in the face of distress.24,25

Specifically, attachment theory proposes that an individual’s attachment system is driven by his or her motivation to maintain proximity to caregivers for safety and regulation.24 During an individual’s formative years, internal working models are formed on the basis of early relationships with caregivers and are eventually transferred to adult romantic patterns.26–28 Bartholomew and Horowitz29 have identified 2 underlying dimensions of adult attachment that include (1) internal working models about self and (2) internal working models about others (each of which can be either positive or negative). These internal working models of self and others have been examined in the context of how they manifest in distinct behavioral strategies in close relationships, which include attachment anxiety (anxiety over relationship issues) and avoidance (discomfort with closeness and interdependence). Insecure attachment representations contribute to pathways of chronic excitation or inhibition in response to threat, namely hyperactivating (attachment anxiety) and deactivating (attachment avoidance) coping strategies.30 These insecure behavioral strategies reflect an adaptive attempt to maintain closeness with a caregiver or to regulate distress, which are both critical after an SCI.

Secure attachment strategies have been related to the recall of positive memories when negative affect is induced, confidence in handling distress, maintenance of mental health during times of stress, positive views of self and others, acknowledgment and expression of emotion, support seeking, and effective coping.31,32 Conversely, insecure strategies have been related to recall of negative memories when negative affect was induced, global distress, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, substance abuse, conduct disorders, personality disorders, and reduced well-being.31–33

These findings support the notion that insecure attachment styles are related to reduced resilience and increased vulnerability for psychopathology. Thus, understanding attachment styles may be of particular importance for those with SCI, as many individuals require some degree of caregiving, especially in the initial stages of injury. The ability for the newly injured individual to communicate effectively with a loved one who is now in a caregiving role can have an impact on overall health. For example, if individuals need assistance with bowel and bladder management because of limited upper extremity mobility, it is critical that they be able to articulate their needs regarding a very intimate activity. Therefore, an individual’s attachment style may not only affect the quality of relationships post SCI but may also have practical implications for intervention. However, despite the applicability of attachment theory to better understanding of the association between social support, resilience, and depression after SCI, currently no work in this area has been completed.

In summary, an individual’s attachment style has been shown to be related to perceptions and utilization of social support34–36 and resilience against negative outcomes such as depression.37–39 Furthermore, social support has been shown to be related to increased resilience in the general population,21,22 as well as among individuals with acquired disabilities.20 Secure attachment and greater perceived social support have been linked to greater resilience; however, this has not been assessed in individuals with SCI.20,40 Thus, because the exact nature of these relationships differs across settings and populations, it is important to further examine the directionality of the relationship in individuals with SCI. This may be especially true for individuals in the immediate days and weeks after injury, because they have to learn how to function in a body that is dramatically different; this can cause understandable anxiety, frustration, and feelings of isolation. Inpatient rehabilitation requires adjustment to physical changes and a steep learning curve to incorporate comprehensive education about all aspects of SCI (eg, associated medical conditions, self-management of ADLs, equipment needs). Thus, quality social support becomes essential to provide stability and encouragement during this period of significant transition.

Therefore, in this study, we examined the association between social support and attachment in relation to resilience and depression in a population of individuals with SCI undergoing inpatient rehabilitation. Specifically, we tested a path model assessing the mediating effects of social support between attachment (attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance) and resilience and depression.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 106 adults with complete or incomplete SCI undergoing a comprehensive rehabilitation program at a freestanding rehabilitation hospital in the southwestern United States. The mean age of the sample was 43.8 years (SD = 16.4), with 64.2% (n = 68) male and 35.8% (n = 38) female. In regard to race/ethnicity, 81% (n = 86) were Caucasian, 14% (n = 15) were African American, 4% (n = 4) were Hispanic, and 1% (n = 1) were other. Almost half of the participants (47.1%; n = 50) were married, with 36% (n = 38) single, 13% (n = 14) divorced, 2% (n = 2) widowed, and 2% (n = 2) separated. Of the sample, 75 (71%) experienced a traumatic SCI, 22 (21%) experienced a nontraumatic SCI, and 9 (8%) had another type of SCI (eg, caused by Guillain-Barré syndrome, tumor). According to the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS), 39 individuals were AIS A (37%); 15, AIS B (14%); 26, AIS C (25%); and 12, AIS D (11%). (Data for 5 patients were missing.) In addition, 51 participants (48%) experienced a cervical level injury, 31 (29%) thoracic, 10 (9%) lumbar, and 3 (3%) sacral. (Data for 11 patients were missing.) After exclusion of 11 patients who experienced injury more than 1 year previously (mean, 3,898.9 days; range, 26 years), the mean time since injury was 36 days (range, 328 days).

Procedures

The procedures followed protocol in accord with the ethical standards of the responsible institutional review board. Potential subjects were screened based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) experienced a traumatic or nontraumatic SCI, (b) currently undergoing inpatient rehabilitation, and (c) between the ages of 18 and 63 years. Subjects were excluded based on the following criteria: (a) severe cognitive impairment and (b) pre-injury psychiatric illness and/or developmental disability. Individuals who met the inclusion criteria were approached in a private setting and provided information regarding the nature of the study, including a brief explanation of the purpose, time involved, risks and benefits, and confidentiality. After participants provided informed consent, a time was scheduled to complete the study measures with a member of the research team. Measures were completed in the participant’s hospital room, and individuals independently completed the instruments if they were functionally able to do so. Total time of completion was typically less than 30 minutes.

Measures

A brief form was used to obtain demographic (ie, age, gender, ethnicity, relationship status) and injury-related information (ie, location and severity of injury, rehabilitation progress). The data were obtained through medical chart reviews by a study team member.

The Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) was used to assess attachment.41 The measure consists of 2 subscales — Avoidance and Anxiety. The Avoidance subscale assesses discomfort with closeness and discomfort depending on others, whereas the Anxiety subscale assesses fear of rejection or abandonment. The ECR is a 36-item self-report scale that uses a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly), with higher scores indicating stronger attachment. Strong internal consistency and test-retest reliability for anxiety and avoidance dimensions obtained over a 6-month period have been reported.33,41 Similarly, studies have provided evidence of good validity.42 In this study, the 2 ECR scales demonstrated strong reliability, with Cronbach’s alphas of .92 for avoidance and .91 for anxiety.

The Social Provisions Scale (SPS) is a 24-item self-report measure of social support developed by Cutrona and Russell.43 The SPS uses a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Six subscales can be created: Attachment, Social Integration, Reassurance of Worth, Reliable Alliance, Guidance, and Opportunity for Nurturance. However, only the global social support scale was used in this study because of the sample size and analysis completed. Evidence of the reliability and validity of the measure has been established among individuals experiencing significant life distress.44 In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the global social support scale was .90.

The 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) was used to measure the resilience of participants.45 The CD-RISC-10 assesses one latent factor of resilience that “reflects the ability to tolerate experiences such as change, personal problems, illness, pressure, failure, and painful feelings.”45(p1026) The measure uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all of the time), with higher scores indicating greater resilience. The CD-RISC short form has demonstrated good reliability (.85) and construct validity and is highly correlated to the original 25-item CD-RISC (r = .92). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the CD-RISC was .85.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a brief 9-item self-report measure of major depressive disorder.46 The PHQ-9 includes statements about an individual’s affective state over the last 2 weeks (eg, “little interest or pleasure in doing things”), which are scored using a Likert scale with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Scores range from 0 to 27: scores of 0 to 4 indicate no depression; 5 to 9, mild depression; 10 to 14, moderate depression; 15 to 19, moderately severe depression; and 20 to 27, severe depression. In a study of 6,000 patients from 2 separate medical settings (primary care clinics and obstetrics and gynecology clinics), the PHQ-9 was found to have excellent internal reliability and good test-retest reliability. In this study, a Cronbach’s alpha of .79 was found.

Initial data examination

Missing data were analyzed with the statistical software package R.47 A 3-step approach was conducted to use the individual and items scales: (1) single imputation of scales was carried out for temporary use in step 2; (2) scale scores were used as auxiliary variables in multiple imputations of item scores, and then they were discarded; and (3) multiple imputation item scores were used to create 10 multiple imputation scales level datasets to be used in the final analyses.48 Two participants were removed because of a failure to complete the majority of the measures. The remaining missing data were found to be missing at random. Expectation-maximization was used to estimate the missing data and was completed at the individual item level and rounded to the nearest whole number. Shapiro-Wilk’s tests of normality were performed, and all scales were found to be nonnormal. Bootstrap interval estimates are given to address the issues of nonnormality and small sample size. Influence plots from individual regression analyses were examined to help identify outliers. One subject had extreme scores on all scales, but the observed scores were in line with theory and normal at the multivariate level.

Model hypotheses and data analyses

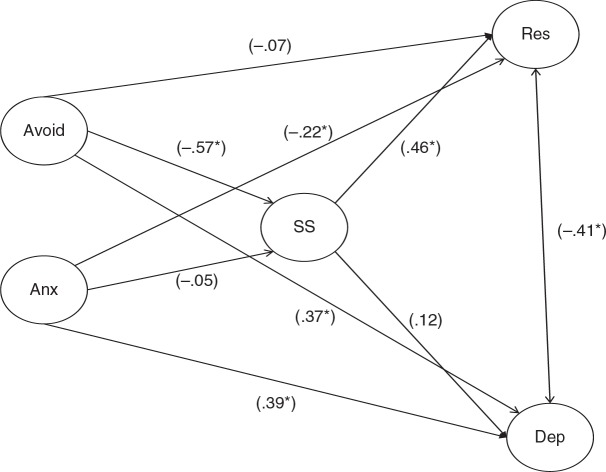

Given that multiple mediators were hypothesized, path analysis was used to test the mediating effects of social support on the relationship between attachment styles (anxiety and avoidance) and resilience or depression (Figure 1). In the model, attachment anxiety and avoidance (ECR) serve as latent exogenous predictor variables, social support (SPS) serves as an intervening latent endogenous variable, and resilience (CD-RISC-10) and depression (PHQ-9) serve as the latent endogenous variables.

Figure 1. Path model of attachment avoidance and anxiety, social support, and resilience and depression. Anx = anxiety; Avoid = avoidance; Dep = depression; Res = resilience; SS = social support.

The statistical software program Mplus49 was used to examine the model, which predicted that social support and depression are negatively related; social support and resilience are positively related; and social support and attachment anxiety and avoidance are negatively related. The model also examines the hypotheses that attachment anxiety and avoidance are negatively related to resilience and positively related to depression. The relationship between resilience and depression is hypothesized to be negative. In regard to mediation effects, the model tested the hypothesis that social support mediates the relationship between the latent exogenous variables attachment anxiety and avoidance and the latent endogenous variables resilience and depression. Multiple fit indices are used to assess the degree of fit for the model, including chi-square model of fit, sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (BIC), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR).

Results

Multiple t tests were conducted between the main variables of interest (attachment anxiety and avoidance, social support, depression, and resilience) and demographic variables (gender, race, injury type, cause of injury). Race was collapsed into “White” and “non-White,” given the small minority distribution. No significant differences were observed across the demographic variables on the main variables. Correlations were also computed for the main variables and age at time of injury, as well as time since injury, with no significant correlations observed. Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients were computed for each scale and are listed in Table 1. The directions of all hypothesized relationships were supported, though not all were statistically significant.

Table 1. Correlations, means, and standard deviations for social support, attachment avoidance and anxiety, resilience and depression.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. | Avoidance (Avd) | 1.00 | ||||

| 2. | Anxiety (Anx) | .29* | 1.00 | |||

| 3. | Social support (SS) | -.57* | -.19 | 1.00 | ||

| 4. | Resilience (Res) | -.35* | -.29* | .48* | 1.00 | |

| 5. | Depression (Dep) | .37* | .40* | -.19 | -.40* | 1.00 |

| Mean | 2.37 | 2.85 | 85.47 | 32.22 | 5.77 | |

| SD | 1.10 | 1.28 | 9.10 | 5.67 | 4.74 |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

P < .01.

Path analyses

The results for the model are shown in Figure 1. The variances accounted for in support of the endogenous variables SPS (R2 = .33), resilience (R2 = .24), and depression (R2 = .17) were significant at the P < .01 level. A significant path was not observed between social support and depression, but the direct path between attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety and depression was significant. Given the lack of association between attachment anxiety and social support, the hypothesis that social support would mediate the relationship between attachment anxiety and resilience and depression was not supported. The mediating effect of social support on the association between attachment avoidance and resilience was the only hypothesized mediating effect that was substantiated for the model (β = -0.25, standard error [SE] = -2.93, P < .05).

The model obtained a BIC value of 2668.7, a CFI value of .927, a chi-square value of 7.86 (P = .01), and an SRMR value of .085. Each of these values suggests a model worthy of further exploration.

Discussion

Significant direct relationships were observed between attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety with depression, as well as attachment anxiety and perceived resilience. In addition, the relationship between attachment avoidance and perceived resilience was mediated by perceived social support, and these results have several clinical implications. The significant direct path between attachment anxiety and depression suggests that individuals with an acquired SCI who have greater attachment anxiety have higher levels of depression. However, the aquirement of SCI in individuals with higher levels of attachment anxiety might only increase their already incompetent view of self and dependency on others, leading to further depression. This model also indicates that attachment avoidance is directly related to lower levels of perceived social support, suggesting that individuals who have higher levels of attachment avoidance expect others to be unavailable and unreliable, so their perception of social support may be negative. Alternatively, because they expect rejection, they may not seek social support and thus receive little. Either way, low perceived social support leads to a more negative perception of the self as less resilient.

In addition, individuals with higher levels of attachment anxiety do not appear to experience lower levels of perceived social support but are more likely to experience depression and perceive themselves as less resilient. This finding suggests that individuals with higher levels of attachment anxiety are able to maintain adequate levels of social support, at least temporarily, but the need to amplify symptoms of distress to elicit care may result in dysphoric affect, leading to depression. It is also possible that internal factors associated with the inability to self-regulate emotions lead to depression independent of social support, which is consistent with previous research linking attachment anxiety and depression.31,50,51

Our model also demonstrates that the relationship between attachment avoidance and perceived resilience is mediated by perceived social support, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of attachment avoidance perceive less social support available, which in turn relates to lower perceived resilience. This finding, in conjunction with the observed direct relationship between attachment avoidance and depression, is also supported by research linking attachment avoidance with a myriad of psychopathology.41,52–54

Individuals with higher levels of attachment avoidance perceived less social support. Given the negative expectations of others that is common among individuals with higher levels of attachment avoidance,29 it is possible that they defensively perceive less available support. It is also possible that given the tendency of individuals with higher levels of attachment avoidance to deactivate emotional expression or reliance on others,32 they do less to maintain social support or actively reject it, so their perceptions are accurate. However, without a nondisability comparison population, findings cannot be attributed to the acquirement of an SCI.

Another important finding was that individuals with higher levels of attachment anxiety do not report significantly lower levels of perceived social support. According to attachment theory, individuals with higher levels of attachment anxiety actively seek to maintain support from significant others through amplification of emotional distress.32 This hyperactivating strategy might function to obtain the needed support in this injured population. Alternatively, they might also tend to perceive their social network as more supportive than is accurate because of more positive expectations of others.29 Given the recency of the acquired SCI for the current sample, it is possible that those with higher levels of attachment anxiety accurately perceive their current social support but, over time, the constant amplification of their distress might lead to increased caregiver burnout.

A higher level of perceived social support was significantly related to perceived resilience, and resilience was negatively related to depression. The path between resilience and depression was bidirectional, so it is unclear whether a possible moderation effect exists. However, attachment avoidance and anxiety did have significant relationships to increased depression, which is consistent with previous findings.55,56

Contrary to predictions, attachment avoidance did not have a significant negative relationship to resilience. Bartholomew and Horowitz29 report that individuals with levels of attachment avoidance have a defensively positive perception of themselves, which allows them to maintain independence from others. This may explain the current finding that attachment avoidance is unrelated to resilience. In addition, the CD-RISC-10 has high face validity and asks about perceptions of the self, which may trigger a need to defensively rate the self as strong. The tendency for an individual with a higher level of attachment avoidance to perceive himself or herself positively is possibly counterbalanced by an SCI that requires assistance from others, resulting in a nonsignificant relationship with resilience.

Finally, individuals with higher levels of attachment anxiety tend to perceive themselves in a less positive manner,29 so it makes theoretical sense that these individuals in our sample rated themselves as less resilient. The tendency for these individuals to amplify distress to elicit care from others would also explain the relationship with depression that we observed.32 The likelihood of individuals with higher levels of attachment anxiety to “cling” to attachment figures might also be hampered by reduced mobility, which could result in a greater degree of helplessness. The nonsignificant relationship between attachment anxiety and social support and the stronger relationship between attachment anxiety and depression than that which was observed with attachment avoidance and depression (despite less perceived social support with increased attachment avoidance) could reflect the amplification of depressive symptoms.

Clinical implications

The finding that attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety have significant relationships with increased depression suggests that moving patients toward more secure attachment should be a clinical focus in attempts to prevent or treat depression. For persons with SCI, individual psychotherapy may allow for assessment of attachment strategies and focus on awareness of problematic coping styles and the development of a secure therapeutic attachment. Couples and family therapy could also be beneficial for individuals with higher levels of attachment avoidance regardless of whether their perceptions of reduced social support are accurate or defensive. On one hand, if the perception is accurate that others cannot be depended on for support, the intervention with the family would be aimed at helping the family provide needed support to the individual with the disability. On the other hand, if the perception is inaccurate and a result of previous relationship failures, then times of support by the family or a partner that present themselves in session could be pointed out to the individual with a disability. The needs of the family members or partner could also be expressed safely in session, which might reduce the negative effects on the support of individuals with disabilities. A secure attachment with the therapist could allow for discussion of sensitive issues such as changes in sexual functioning, role changes, and the psychological impact of caregiving on the family or partner that might not otherwise be discussed.

It should be noted that the treatment of individuals during inpatient rehabilitation could differ in several ways from outpatient treatment. Whereas individuals at this specific inpatient hospital would receive biweekly or even daily psychotherapy sessions based on need, outpatients may only be seen once every few weeks or months. The inpatient setting is also inherently supportive, as individuals have a built-in support network, including the multidisciplinary team of physical, occupational, speech, and recreation therapists, nurses, and physicians. Additionally, inpatients usually have the experience of being around others with similar injuries, thus creating a peer support network of individuals who understand their unique experiences. During outpatient treatment, individuals would likely not have the same level of support, either from professionals or peers. These differences could dictate the intensity of treatment as well as the development of a secure attachment with the therapist.

Limitations and future research

It is important to note that there were several limitations with this study. First, the sample only consisted of inpatients from one facility, resulting in a small sample size that is only representative of one setting. With several paths in the model approaching statistical significance, a larger sample size may have resulted in different pathways reaching significance.

Second, the study proposed a one-time assessment of the subject, so no longitudinal data were gathered. As a result, several findings could be a result of the inpatient rehabilitation setting and typically recent nature of the injury. Follow-up measurements after discharge could assess whether a temporary spike in social support is experienced during inpatient rehabilitation but declines after discharge. Future studies could also include assessment of the caregiver’s attachment style to address likely treatment by the caregiver to the individual who acquired the disability.

Finally, data were only collected from the inpatients and did not include family perceptions. Future efforts could involve completing measures with family members to provide a point of comparison and to identify differences to allow for clinical intervention. Issues of caregiver stress and other negative reactions commonly found with support systems could be explored in relation to the individual’s experience.

Conclusions

The findings from this study have implications for the future treatment of individuals who have acquired an SCI. Because attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety appear to increase the risk of depression in individuals who have acquired an SCI, the issue should be addressed through individual, couples, or family therapy modalities. Each modality provides the context for addressing attachment patterns as well as the ability to develop and use a more secure social support network. Identification of an individual’s attachment strategy and treatment could help aid him or her through the difficult time after an acquired SCI by promoting resilience and avoiding negative outcomes such as depression. While sustaining an SCI will likely be perceived as a negative event, it might also provide a sensitive time to intervene with longstanding attachment patterns, leading to greater well-being.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/ Updated 2013. Accessed February27, 2014.

- 2.Craig A, Tran Y, Middleton J. Psychological morbidity and spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2009;47(2):108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hancock KM, Craig AR, Dickson HG, Chang E, Martin J. Anxiety and depression over the first year of spinal cord injury: A longitudinal study. Paraplegia. 1993;31(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollard C, Kennedy P. A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and posttraumatic psychological growth following spinal cord injury: A 10-year review. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;12:347–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott TR, Frank RG. Depression following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(8):816–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Krause JS, Tulsky D, Tate DG. Symptoms of major depression in people with spinal cord injury: Implications for screening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(11):1749–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dryden DM, Saunders LD, Jacobs P, et al. Direct health care costs after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Trauma. 2005;59(2):443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Tate DG, Wilson CS, Temkin N. Depression after spinal cord injury: Comorbidities, mental health service use, and adequacy of treatment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(3):352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders LL, Krause JS, Focht KL. A longitudinal study of depression in survivors of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(1):72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause JS, Saladin LK, Adkins RH. Disparities in subjective well-being, participation, and health after spinal cord injury: A 6-year longitudinal study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2009;24(1):47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonanno GA, Kennedy P, Galatzer-Levy I, Lude P, Elfström ML. Trajectories of resilience, depression, and anxiety following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2012;57(3):236–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catalano D, Chan F, Wilson L, Chiu C, Muller VR. The buffering effect of resilience on depression among individuals with spinal cord injury: A structural equation model. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(3):200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilic SA, Dorstyn DS, Guiver NG. Examining factors that contribute to the process of resilience following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51(7):553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monden KR, Trost Z, Catalano D, et al. Resilience following spinal cord injury: A phenomenological view. Spinal Cord. 2014;52(3)197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin J, Chae J, Min J, et al. Resilience as a possible predictor for psychological distress in chronic spinal cord injured patients living in the community. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36(6):815–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White B, Driver S, Warren AM. Resilience and indicators of adjustment during rehabilitation from a spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2010;55(1): 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loss Bonanno G., trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely adversive events ? Am Psychol. 2004;59(1):20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driver S, Warren AM, Reynolds M, et al. Identifying predictors of resilience at inpatient and 3-months post spinal cord injury [published online ahead of print October 9, 2014]. J Spinal Cord Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chronister JA, Johnson EK, Berven NL. Measuring social support in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(2):75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chawalisz K, Vaux A. Social support and adjustment to disability. In: Frank R, Elliot T, eds. Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000:537–552. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luthar S. Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, eds. Developmental Psychopathology. Volume 3: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006:739–795. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masten AS. Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutten M. Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for family therapy. J Fam Ther. 1999;21(2):119–144. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Volume 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Volume 2. Separation: Anxiety and Anger. New York: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waters E, Merrick S, Treboux D, Crowell J, Albersheim L. Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):684–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B. Attachment from infancy to early adulthood in a high-risk sample: Continuity, discontinuity, and their correlates. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton C. Continuity and discontinuity of attachment from infancy through adolescence. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):690–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(2):226–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attach Hum Dev. 2002;4(2): 133–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikulincer M, Florian V. Attachment style and affect regulation: Implications for coping with stress and mental health. In: Fletcher G, Clark M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Interpersonal Process. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2001:537–557. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Pereg D. Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motiv Emotion. 2003;27(2):77–102. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez FG, Gormley B. Stability and change in adult attachment style over the first-year college transition: Relations to self-confidence, coping, and distress patterns. J Couns Psychol. 2002;49(3):355–364. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins NL, Feeney BC. Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: Evidence from experimental and observational studies. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87(3):363–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Declercq F, Palmans V. Two subjective factors as moderators between critical incidents and the occurrence of post traumatic stress disorders: Adult attachment and perception of social support. Psychol Psychother. 2006;79:323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Florian V, Mikulincer M, Bucholtz I. Effects of adult attachment style on the perception and search for social support. J Psychol. 1995;129(6):665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreira JM, de Fátima Silva M, Moleiro C, et al. Perceived social support as an offshoot of attachment style. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;34(3):485–501. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodin G, Walsh A, Zimmerman C, et al. The contribution of attachment security and social support to depressive symptoms in patients with metastatic cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16(12):1080–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel DL, Wei M. Adult attachment and help-seeking intent: The mediating roles of psychological distress and perceived social support. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(3):347–357. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment theory and research: Core concepts, basic principles, conceptual bridges. In: Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, eds. Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. 2nd ed. New York,: Guilford Press; 2007:650–677. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21(3):267–283. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, Zakalik RA. Cultural equivalence of adult attachment across four ethnic groups: Factor structure, structured means, and associations with negative mood. J Couns Psychol. 2004;51(4):408–417. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cutrona CE, Russell DW. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In: Jones W, Perlman D, eds. Advances in Personal Relationships. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1987:37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baron RS, Cutrona CE, Hicklin D, Russell DW, Lubaroff DM. Social support and immune function among spouses of cancer patients. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(2):344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su Y, Gelman A, Hill J, Yajima M. Multiple imputations with diagnostics (mi) in R: Opening windows into the black box. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(2):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baraldi AN, Enders CK. An introduction to modern missing data analyses. J Sch Psychol. 2010;48(1): 5–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cole-Detke H, Kobak R. Attachment processes in eating disorder and depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(2):282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M, et al. The relation of attachment status, psychiatric classification, and response to psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(1):22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mikulincer M. Adult attachment style and individual differences in functional versus dysfunctional experiences of anger. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(2):513–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riggs SA, Sahl G, Greenwald E, Atkison H, Paulson A, Ross CA. Family environment and adult attachment as predictors of psychopathology and personality dysfunction among inpatient abuse survivors. Violence Vict. 2007;22(5):577–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zuroff DC, Fitzpatrick DK. Depressive personality styles: Implications for adult attachment. Pers Individ Dif. 1995;18(2):253–365. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dozier M, Stovall-McClough KC, Albus KE. Attachment and psychopathology in adulthood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, eds. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2008:718–744. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams NL, Risking JH. Adult romantic attachment and cognitive vulnerabilities to anxiety and depression: Examining the interpersonal basis of vulnerability models. J Cogn Psychother. 2004;18(1):7–24. [Google Scholar]