Abstract

Purpose

Glaucoma medications can reduce intraocular pressure and improve clinical outcomes when patients adhere to their medication regimen. Providers often ask glaucoma patients to self-report their adherence, but the accuracy of this self-report method has received little scientific attention. Our purpose was to compare a self-report medication adherence measure with adherence data collected from Medication Event Monitoring Systems (MEMS) electronic monitors. Additionally, we sought to identify which patient characteristics were associated with over-reporting adherence on the self-reported measure.

Methods

English-speaking adult glaucoma patients were recruited for this observational cohort study from six ophthalmology practices. Patients were interviewed immediately after a baseline medical visit and were given MEMS containers, which were used to record adherence over a 60-day period. MEMS data were used to calculate percent adherence, which measured the percentage of the prescribed number of doses taken, and timing adherence, which assessed the percent doses taken on time. Patients self-reported adherence to their glaucoma medications on a visual analog scale (VAS) approximately 60 days following the baseline visit. Bivariate analyses and logistic regressions were used to analyze the data. Self-reported medication adherence on the VAS was plotted against MEMS adherence to illustrate the level of discrepancy between self-reported and electronically-monitored adherence.

Findings

The analyses included 240 patients who returned their MEMS containers and who self-reported medication adherence at the 60-day follow-up visit. When compared with MEMS-measured percent adherence, 31% of patients (n=75) over-estimated their adherence on the VAS. When compared with MEMS-measured timing adherence, 74% (n=177) of patients over-estimated their adherence on the VAS. For the MEMS-measured percent adherence, logistic regression revealed that patients who were newly prescribed glaucoma medications were significantly more likely to over-report adherence on the VAS (OR=3.07, 95% CI: 1.22, 7.75). For the MEMS–measured timing adherence, being male (chi-square=6.78, p=0.009) and being prescribed glaucoma medications dosed multiple times daily (chi-square =4.02, p=0.045) were significantly associated with patients over-reporting adherence on the VAS. However, only male gender remained a significant predictor of over-reporting adherence in the logistic regression, (OR=4.05, 95% CI: 1.73, 9.47).

Implications

Many glaucoma patients, especially new patients, over-estimated their medication adherence. Because patients were likely to over-report percent doses taken and timing adherence, providers may want to ask patients additional questions about when they take their glaucoma medications in order to potentially detect issues with taking glaucoma medications on time.

Keywords: glaucoma, self-reported medication adherence, electronically-monitored medication adherence

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide affecting over 60 million people.1,2 As the global population ages, it is projected that glaucoma will affect approximately 110 million by 2040.2 Glaucoma is often detected late, usually after patients have already experienced extensive and irreversible damage3. Subsequent glaucoma management is vital to preserve vision.3,4 Topical medications, which lower intraocular pressure (IOP), are used to delay the progression of glaucoma; however, patients may not notice the benefits of using these medications because glaucoma is an asymptomatic, slowly progressive chronic disease.5–7 Additionally, approximately one-half of those who start therapy on IOP-lowering medications discontinue them within six months.8,9 Patients who are nonadherent to their IOP-lowering medications risk being prescribed additional glaucoma medications or hastening the progression of glaucoma. Therefore, regular and accurate assessment of medication adherence in clinical practice is essential.

Pharmacy refill methods10–12, electronic monitoring13–19, and self-report measures15,18,20 have all been used to assess the medication adherence of glaucoma patients. Estimates of adherence vary based on the method being used; pharmacy refill records have produced the lowest estimates of glaucoma medication adherence while self-report measures have yielded the highest adherence estimates.15 Refill records are limited in that they may contain missing information21, are restricted in the types of adherence that can be assessed (e.g., interdose intervals cannot be calculated), and may be too cumbersome for providers to incorporate into practice. Although electronic monitors have been referred to as the “gold standard” for adherence measurement22–24, their cost makes them impractical for monitoring adherence in clinical settings. Furthermore, certain electronic monitors can only be used with specific medications (e.g., Travatan Dosing Aid).16,17,25,26 Neither pharmacy refill records nor electronic monitoring can verify whether the patient actually instilled their eye drops.

Self-reported adherence measures may be the most cost-effective and feasible way for providers to assess the adherence of glaucoma patients, although their validity is often called into question. A few studies have examined the validity of self-reported measures against objective measures (e.g., pharmacy records or electronic monitors) in glaucoma patients.15,18 Both studies found that patients with glaucoma tended to over-estimate their adherence to glaucoma medications.15,18 Furthermore, Cook et al15 found that the correlation between MEMS and self-report was only 0.31. These previous examinations of self-report versus objective measures have been limited in several respects. The Cate et al study18 was limited to a single study site, a single medication (travoprost), and only had 88 participants. Cook15 examined a single type of MEMS-measured adherence (percentage of days with correct adherence) and was also restricted to patients taking a single glaucoma medication.

The objectives of this multi-site study were (1) to compare patients’ self-reported adherence to glaucoma medications via the use of a visual analog scale as compared with MEMS-measured percent adherence and MEMS-measured timing adherence, and (2) to examine the patient characteristics of those who over-reported their adherence on the visual analog scale. The current study builds upon previous studies by examining discrepancies in self-reported adherence by using two measures of electronically-monitored adherence for a sample (n=240) that included glaucoma patients who were taking multiple medications. The study is also the first to examine which patient characteristics are associated with glaucoma patients over-reporting adherence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

From December 2009 through July 2012, English-speaking adults with primary open-angle glaucoma were recruited at six ophthalmology clinics located in four states (Georgia, North Carolina, Maryland, Utah), and were followed for approximately 8 months. At each clinic, providers (e.g., ophthalmologists) gave their written consent. Clinic staff referred potentially eligible patients to a clinic-based research assistant. The research assistant explained the study to the patients and obtained informed consent from the patient before the patient’s baseline medical visit. Eligibility requirements included being at least 18 years of age, being able to speak and read English, being considered either a glaucoma or a glaucoma suspect patient, being mentally competent as determined by the Mental Status Questionnaire27, and being prescribed at least one glaucoma medication. After the medical visit, the research assistant interviewed the patient using a survey. Ineligible patients were thanked and given $5. The research assistant furnished the patient with one MEMS container for each prescribed glaucoma medication, and demonstrated how to place the glaucoma medication inside the MEMS container and how to use the MEMS container. This “bottle within a bottle” system has been used previously to measure glaucoma patient medication adherence.14,15,17

Approximately 60 days after their baseline medical visit, the patients returned to the clinic for a follow-up visit. At that time, the research assistant interviewed the patient using a survey that included the visual analog scale (VAS) and downloaded the data from each MEMS container. Eligible patients enrolled in the study were given $20 at the initial and the follow-up visit.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of North Carolina, Duke University, Emory University, and the University of Utah.

Patient Characteristics

The research assistant gathered data regarding patient age, race, gender, years of education, household income, and whether the patient was newly prescribed a glaucoma medication from the patient during the patient interview after the patient’s medical visit. Self-reported patient race was measured as a categorical variable (White, African American, Asian, Native American, and Hispanic), and then recoded into African American and non-African American. Annual household income was measured as a categorical variable, and then recoded into a dichotomous variable (< $20,000 versus ≥ $20,000); $20,000 is the approximate federal poverty level for a family of three.28 Whether the patient was newly prescribed glaucoma medications was measured as a dichotomous variable (new to medication or already using medication).

Information about the patient’s glaucoma severity was extracted from the patient’s medical record. Specifically, the research assistant recorded the patient’s mean deviation, in decibels (dB), from the patient’s most recent reliable visual field test for each eye. We classified the severity of glaucoma using the mean deviation of the worse eye, and recoded it as mild (≥ −6 dB), moderate (between −12 dB and −6 dB), or severe (≤ −12 dB).29

The research assistant extracted the number of prescribed glaucoma medications and the corresponding dosing regimen from the patient’s medical record. The number of glaucoma medications was measured as a continuous variable, and then recoded into a dichotomous variable (one versus more than one). The medication dosing regimen was measured as a dichotomous variable (once daily versus more than once daily).

Self efficacy

During the initial interview, patients completed a 10-item, validated, glaucoma medication self-efficacy questionnaire.19,30 This glaucoma medication adherence self-efficacy questionnaire assesses patients’ confidence in medication adherence and has been strongly correlated with medication adherence as measured with electronic monitoring.30 Responses for each item are “not at all confident” (coded as 1), “somewhat confident” (coded as 2), and “very confident” (coded as 3). Items were summed, with scores ranging from 10 to 30. Higher scores indicating greater glaucoma medication self-efficacy. The internal consistency of the self-efficacy questionnaire in this study was α =0.94.

Medication Adherence

The visual analog scale (VAS), a self-report measure of adherence, has been validated against prescription medication refills for chronic disease patients.31–34 As part of the follow-up visit interview, the research assistant asked the patient “All things considered, how much of the time do you use ALL of your glaucoma medications EXACTLY as directed?” and instructed the patient to place a mark through the 100 mm line to indicate their answer (range is 0 mm = None of the time, 100 mm = All of the time).31–35 This question can be seen in Figure 1. Using a metric ruler, placing the 0 mm portion of the ruler on the left-most portion of the VAS line, the data entry person measured the placement of the patient-placed mark in millimeters. In order to facilitate comparisons between the VAS and MEMS, we converted the measurement on the VAS from 100 mm to 100%.35

Figure 1.

The question containing the visual analog scale (VAS) on the survey

Electronic monitoring of medication adherence was assessed over a 60-day period via MEMS (AARDEX, MeadWestvaco Corporation, Richmond, VA, USA). We chose to measure the first 60 days because the most of the follow-up visits occurred between 4 and 12 weeks after the initial visit. This electronic monitor records the date and time of each bottle opening. The model that was used in this study did not have a LCD display on the cap. If a patient was assigned more than one MEMS container, then color-coded labels were placed on the outside of the MEMS bottle so that the patient knew which MEMS bottle contained which glaucoma medication.

We used the data from the MEMS device to examine the percent doses prescribed that were taken during the 60-day period (MEMS-measured percent adherence). For example, if a patient were prescribed a twice daily medication, then the bottle should have been opened 120 times over a 60-day period. If the patient only opened the bottle 80 times, then their percent adherence would be 80 divided by 120, or 75%. We capped the maximum MEMS-measured percent adherence at 100% since the VAS score could not be greater than 100. If the patient was prescribed more than one glaucoma medication, the average of the percent doses prescribed was used since the wording on the VAS question referred to how the patient takes all glaucoma medications instead of a referring to a specific medication.

Additionally, the MEMS-measured timing adherence assessed the percent doses taken on time during the 60-day period. We used the default MEMS measure of on-time – such that if a patient was prescribed a once daily dosing regimen, then taking the medication on time was considered every 24 hours ± 6 hours. If the dosing regimen was twice daily, then taking the medication on time meant taking it every 12 hours ± 3 hours. If the patient was prescribed more than one glaucoma medication, the average of the on-time adherence percentage was used.

Data Analyses

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 (Armonk, NY, USA). We set the a priori level of statistical significance at p < 0.05. First, we used descriptive statistics to characterize the patient demographics. Then, we used t-tests and chi-square tests to determine which patient characteristics (age, gender, race, years of formal education, household income, was newly prescribed glaucoma medications, glaucoma severity, number of prescribed glaucoma medications, glaucoma medication dosing frequency, and glaucoma medication self-efficacy) were associated with over-reporting adherence on the VAS versus MEMS. Also, logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine which patient characteristics predicted whether the patient over-reported adherence on the VAS as compared with that calculated via MEMS. If the VAS medication adherence was greater than the MEMS-measured percent adherence, then the patient over-reported adherence on the corresponding scale; otherwise, the patient did not over-report adherence. Lastly, we plotted the electronically-measured percent adherence against the self-reported adherence for each patient.

RESULTS

Study Population

Eighty-six percent (n=279) of eligible patients participated in this study. Thirty patients (11%) patients did not have either MEMS-measured adherence values because they either did not return a bottle or returned a bottle where the data could not be downloaded (e.g. hardware failure). Patient characteristics are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Patient characteristics (N = 279)

| Characteristic | % (N) |

|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 40.9 (114) |

| Race, African American | 35.5 (99) |

| Patient newly prescribed glaucoma medication at baseline | 18.3 (51) |

| Glaucoma severity in worse eye, Severe | 15.1 (42) |

| Number of glaucoma medications | |

| One | 67.4 (188) |

| Two | 28.3 (79) |

| Three | 3.9 (11) |

| Four | 0.4 (1) |

| Daily dosage of glaucoma medication | |

| Once daily | 59.5 (166) |

| More than once daily | 36.9 (103) |

| Household income | |

| Less than $20,000 | 10.8 (30) |

| $20,000 or more | 65.6 (183) |

| Do not know / Do not want to answer | 23.3 (65) |

| Mean (Standard Deviation); Range | |

| Age | 65.8 (12.8) |

| 21 – 93 | |

| Years of schooling | 15.1 (3.5) |

| 5 – 26 | |

| Self-efficacy glaucoma medications | 27.8 (3.1) |

| 13 – 30 |

Of the 279 patients who participated in the study, 240 had both a VAS score and a 60-day MEMS-measured adherence value for each of their prescribed glaucoma medication. The median self-reported adherence percentage on the VAS was 95.0% (interquartile range: 84.0 – 98.0). The median MEMS-measured percent adherence was 97.5% (interquartile range: 88.1 – 100.0) and the median MEMS-measured timing adherence was 83.7% (interquartile range: 58.4 – 94.9). Included in this data is one patient who did not use any of the prescribed glaucoma medications during the study period. The median MEMS-measured percent adherence did significantly differ from the median self-reported adherence (z=−3.33, p=0.001). The median MEMS-measured timing adherence did significantly differ from the median self-reported adherence (z=−8.78, p<0.0001).

The sensitivity of the VAS adherence being at least 80% was 0.85, but the specificity was 0.38 when compared with the MEM-measured percent adherence. Also, when compared with the MEMS-measured timing adherence, the sensitivity of the VAS adherence being at least 80% was 0.92, but the specificity was 0.32.

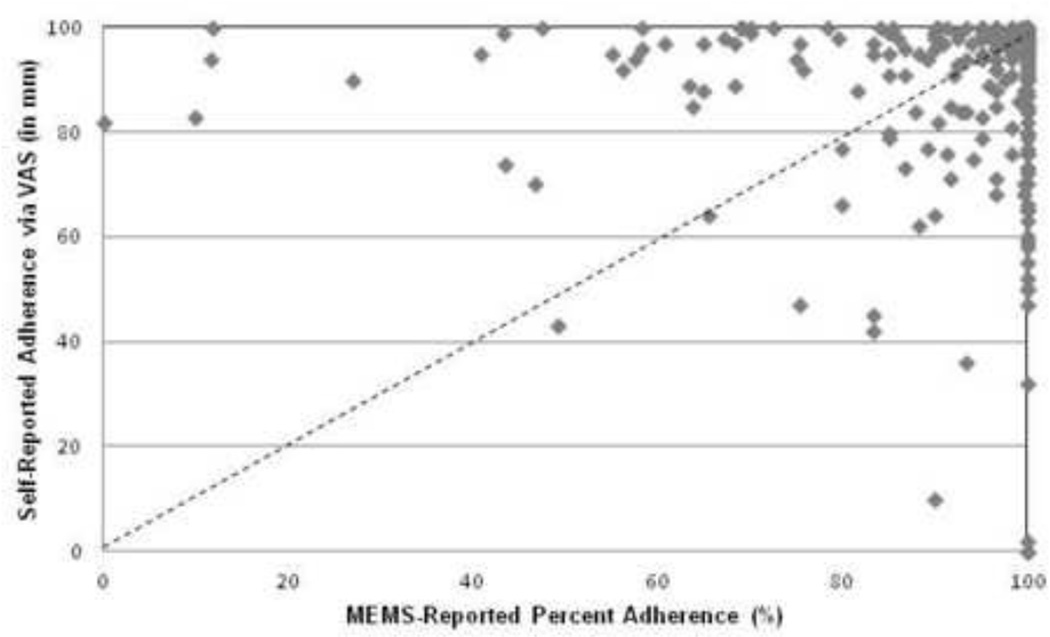

Thirty-one percent (n=75) of patients over-estimated their adherence on the VAS when compared with the MEMS-measured percent adherence and 58% (n=140) under-estimated their adherence. The self-reported adherence on the VAS had a modest relationship with the MEMS-measured percent adherence (r=0.32, p<0.001). Figure 2 illustrates the scatter plot displaying MEMS-measured percent adherence against self-reported medication adherence on the VAS.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the 60-day MEMS-measured adherence and patients’ self-reported adherence assessed by visual analog scale (VAS) at the follow-up visit (N = 240)

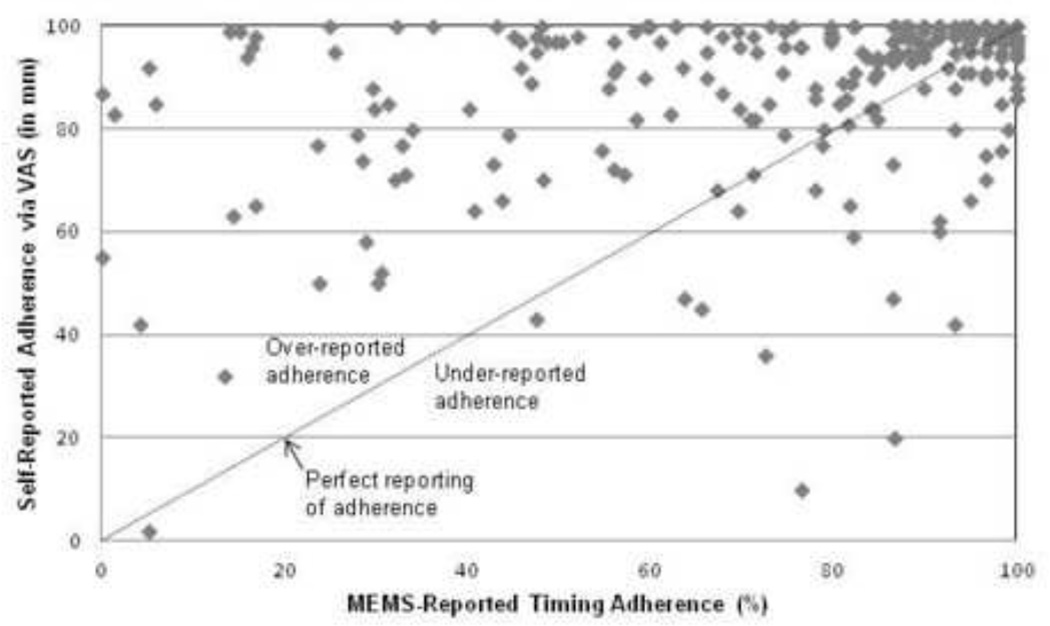

Seventy-four percent (n=177) of patients over-estimated their adherence on the VAS when compared with the 60-day MEMS-measured timing adherence value and 25% (n=59) of patients under-estimated their adherence. There was a modest relationship between the VAS score and the MEMS-measured timing adherence (r=0.38, p<0.001). Figure 3 presents the scatter plot showing MEMS-measured timing adherence against self-reported medication adherence on the VAS.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the 60-day MEMS-measured timing adherence and patients’ self-reported adherence assessed by visual analog scale (VAS) at the follow-up visit (N = 240)

Table II presents the characteristics of the glaucoma patients who over-reported adherence to their medication regimens on the VAS when compared with the MEMS-measured percent adherence. Patients who were newly prescribed medications at the baseline visit were significantly more likely to over-report their adherence on the VAS as compared with patients who were already using medications at the baseline visit (chi-square=15.2, p<0.001). Logistic regression revealed that patients who were newly prescribed glaucoma medications were significantly more likely to over-report adherence on the VAS as compared with those already using medications at the baseline visit (OR=3.07, 95% CI: 1.22, 7.75, p=0.018).

Table II.

Patient characteristics1 of those who over-reported adherence to glaucoma medications on the VAS as compared with MEMS-measured adherence

| Over-reported adherence on the VAS (N = 75) |

P | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 33 / 75 (44%) | 0.501 |

| Race, African American | 28 / 75 (37%) | 0.505 |

| Patient newly prescribed glaucoma medication at baseline | 25 / 75 (33%) | < 0.001 |

| Glaucoma severity in worse eye, Severe | 15 / 71 (21%) | 0.278 |

| Prescribed more than 1 glaucoma medications | 19 / 75 (25%) | 0.052 |

| Glaucoma medication dosed more often than once daily | 24 / 72 (33%) | 0.905 |

| Household income, <$20,000 annually | 6 / 57 (11%) | 0.474 |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | ||

| Age | 65.3 (12.7) | 0.494 |

| Years of schooling | 15.2 (3.8) | 0.351 |

| Self-efficacy glaucoma medications, short form | 27.6 (3.4) | 0.808 |

Patient characteristics as defined in the Methods section (e.g., male patients compared with female patients, African American patients compared with non-African American patients)

Table III presents the characteristics of the patients who over-reported adherence to their medication regimens on the VAS when compared with the MEMS-measured timing adherence. Males (chi-square=6.78, p=0.009) and patients prescribed glaucoma medications more than once daily (chi-square=4.02, p=0.045) were significantly more likely to over-estimate their adherence. Logistic regression revealed that only males (OR=4.05, 95% CI: 1.73, 9.47, p=0.001) were significantly more likely to over-report adherence on the VAS when compared with MEMS-measured timing adherence.

Table III.

Patient characteristics1 of those who over-reported adherence to glaucoma medications on the VAS as compared with MEMS-measured timing adherence

| Over-reported adherence on the VAS (N = 177) |

P | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 81 / 177 (46%) | 0.009 |

| Race, African American | 63 / 177 (36%) | 0.547 |

| Patient newly prescribed glaucoma medication at baseline | 35 / 177 (20%) | 0.321 |

| Glaucoma severity in worse eye, Severe | 33 / 166 (20%) | 0.214 |

| Prescribed more than 1 glaucoma medications | 63 / 177 (36%) | 0.497 |

| Glaucoma medication dosed more often than once daily | 77 / 170 (45%) | 0.045 |

| Household income, <$20,000 annually | 18 / 135 (13%) | 0.973 |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | ||

| Age | 65.4 (12.8) | 0.605 |

| Years of schooling | 14.9 (3.6) | 0.508 |

| Self-efficacy glaucoma medications, short form | 27.8 (3.2) | 0.736 |

Patient characteristics as defined in the Methods section (e.g., male patients compared with female patients, African American patients compared with non-African American patients)

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine whether there are discrepancies between self-reported adherence and two measures of electronically-monitored adherence (percent adherence, timing adherence) in a sample of glaucoma patients that included patients who were taking multiple medications. We found that patients’ self-reported medication adherence as measured with a visual analog scale did not correlate strongly with electronically-measured percentage or timing adherence over a 60-day period. Patients were more likely to over-report timing adherence than percentage adherence, and patients who were new to medications and men were more likely to over-report adherence. This study focused on the over-reporting of medication adherence rather than under-reporting since the consequences of over-reporting may lead to optic nerve degeneration which could ultimately lead to blindness.

When compared with the MEMS-measured percent adherence, nearly one in three patients over-estimated their adherence on the VAS, which is lower than what prior studies36,37 have found in other chronic disease states. However, this was higher than a previous study of glaucoma patients, which found a discrepancy of approximately 15% between MEMS-measured percent adherence and a self-report adherence measure.15 The level of discrepancy we found was more similar to a previous study of 88 glaucoma patients where electronically measured adherence detected approximately 25% more non-adherent patients when compared with selfreport.18 When compared against the MEMS-measured timing adherence, approximately three out of four patients over-reported their adherence on the VAS, which is similar to what studies have found in other chronic diseases.36,37 Taken together, these findings suggest that patients using medications chronically tend to over-estimate adherence to their prescribed dosing schedule.

When compared with the MEMS-measured percent adherence, patients who were newly prescribed medications at the baseline visit were significantly more likely to over-report their adherence on the VAS as compared with those who were already using glaucoma medications at the baseline visit. Previous research18 did not find any significant differences in electronically-measured adherence rates between those glaucoma and ocular hypertension patients who were new versus established on drops; however, that study had a much smaller patient sample. Patients who are new to drops may have more difficulty integrating a new medication into their daily routine. Additionally, many new glaucoma patients discontinue their medications within the first six months of treatment8,9. Taken together, providers should attempt to accurately assess the medication adherence of new patients at the first follow-up visit following the initiation of glaucoma pharmacotherapy. Because patients were likely to over-report percent doses taken and timing adherence, providers may want to ask patients additional questions about when they take their glaucoma medications in order to potentially detect issues with taking glaucoma medications on time, by starting a conversation such as, “some patients have a hard time remembering to take their glaucoma medications on a consistent schedule, tell me how you remember to take your medications on time”.

Males over-reported their adherence on the VAS as compared to the MEMS-measured timing adherence, which is similar to a study26 involving glaucoma patients self-reporting adherence. Additionally, patients who were prescribed glaucoma medications dosed multiple times per day were significantly more likely to over-report adherence on the VAS, which is similar to what other studies have found.15,26,37 This may be due to complex dosing regimens that may interfere with the patient’s normal activities and is a good reason for providers to simplify medication regimens whenever possible. If a glaucoma medication is to be taken multiple times daily, the provider should help the patient develop a plan (e.g., take before breakfast and after dinner) to incorporate this into the patient’s daily life. Other patient characteristics, such as years of education, household income, and age, were not significantly associated with over-reporting medication adherence on the VAS, contrasting the results of other studies, which may be due, in part, to the differences in the patient populations amongst the studies.15,38

There may be several reasons why patients over-estimate their adherence. First, information on the purpose of using glaucoma eye drops, the importance of adhering to the prescribed regimen, or the frequency with which to administer drops might be inadequately communicated to or misunderstood by the patient.39 As a result, the patient may self-administer their medications less frequently than prescribed while genuinely believing that they are taking their medications as their provider prescribed. Furthermore, some patients may have felt the need to please the research assistant during the interview by stating better adherence than actuality (i.e. social desirability bias). Also, some patients may not have remembered missing doses when self-reporting adherence. Even so, when comparing the average VAS self-reported adherence with the average MEMS electronically-monitored adherence, it was surprising that this was relatively close when comparing 60-day adherence using electronic monitor with a patient-reported adherence measure. In a small study of patients who had been taking at least one antihypertensive medication on a stable medication regimen for at least 3 months, it was found that the VAS medication adherence at 30 days was more closely related to adherence measured by electronic monitors than the VAS medication adherence at either 7 or 14 days.41 However, that study did not evaluate the self-reported medication adherence on the VAS with that measured with electronic monitors for longer than 30 days.

The wording of the VAS questions may have influenced how the patients self-reported adherence in this study. The wording of the question was “All things considered, how much of the time do you use ALL of your glaucoma medications EXACTLY as directed?” with instructions for the patient to place a mark anywhere on the 100 mm line for the patient to indicate their adherence. Even if the written instructions were not clearly understood by the patients, research assistants could clarify the question and answer any questions that the patient had with this particular question. We did not place visual cues on the VAS line to provide general percentage guidance (i.e., every 10%). Furthermore, the instructions did not provide a specific time period for recall, so patients may have been recalling their adherence over the past few days or weeks rather than the past 60 days. Fewer people over-estimated their adherence on the VAS when compared to the MEMS-measured percent adherence and MEMS-measured timing adherence values (31% and 74% respectively). Because the time at which patients take their medications may not be information that is readily accessible cognitively, patients may need additional questions that ask specifically what time of day they take their medications and whether they believe they are taking their medications on time each day in order to accurately recall this information. This might also explain why the VAS had moderate sensitivity and had poor specificity for detecting when a glaucoma patient was at least 80% adherent to their glaucoma medication regimen. Indeed, future research is needed to identify what changes are needed to the VAS to make it more useable in the glaucoma patient population. Additionally, future research should evaluate whether there is a difference in patient adherence across medication classes (e.g., prostaglandin analogs, beta blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, alpha agonists, combination products).

An unexpected result from this study is that the glaucoma medication self-efficacy was not correlated with either MEMS adherence measure. This may be due to the differences in the patient populations between this study and one validating this questionnaire19. This current study had fewer males, more patients who were newly prescribed glaucoma medications, and more patients prescribed a single glaucoma medication than the study which validated the self-efficacy questionnaire.

There were limitations in our study, and as such, results should be interpreted with caution. First, the patient self-reported adherence to a research assistant and may have given a different estimate of adherence than they would to a provider. Another limitation was that patients were told that the MEMS bottle would be used to monitor their medication-taking behavior, which may have influenced their adherence as well as their estimations of adherence. To minimize this potential adherence-enhancing effect of using the electronic monitors, we evaluated adherence over 60 days. Also, the MEMS bottle only measured whether the patient opened the bottle instead of whether the patient took the dose or instilled the eye drop correctly. As such, patients may have taken into account additional factors when placing the mark on the VAS indicating their adherence to glaucoma medications which may account of the large number of patients who under-reported their adherence. Additionally, selection bias could be another limitation since the ancillary staff did not track the characteristics of the patients who declined to speak with the research assistant to learn more about the study. Also, patients self-reported whether they were newly prescribed a glaucoma medication or were already using a glaucoma medication at the initial visit. However, even with these limitations, this study has found several patient characteristics that were associated with glaucoma patients who over-report adherence.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this study found that many glaucoma patients over-reported their glaucoma medication adherence on the VAS as compared with electronic monitors. Providers should be aware of this as a possible reason for a patient’s non-response to treatment. Because more objective methods of determining adherence, such as pharmacy refill records or electronic monitors, may be too time-consuming or expensive for providers to incorporate into their practices, providers may need to use non-threatening patient interview techniques40 to elicit reports of non-adherence during medical visits until more valid and reliable self-report measures can be developed and tested. Future studies should evaluate whether wording or visual modifications on self-reported adherence measures could elicit more accurate and reliable reports of medication adherence from glaucoma patients.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

This project was supported by grant EY018400 (PI: Betsy Sleath) from the National Eye Institute and by grant UL 1RR02574 7 (PI: Betsy Sleath) from the National Center of Research Resources, NIH. NIH had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Dr. Carpenter’s salary was partially supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR000084. Dr. Hartnett is a consultant for Axikin Pharmaceuticals and receives support from NIH/NEI EY015130, EY017011. Dr. Lawrence does paid lectures for Alcon Laboratories. Dr. Robin has been a consultant for Biolight, Lupin Pharmaceuticals, and Sucampo and he does paid lectures for Merck and Allergan. Also, Dr. Robin has been a consultant for and has stock options in Glaucos, and is on the board of Aerie Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

Drs. Sayner, Blalock, Carpenter, Muir, Giangiacomo, Tudor, and Sleath indicate no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Quigley HA. Glaucoma. Lancet. 2011 Apr 16;377(9774):1367–1377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global Prevalence of Glaucoma and Projections of Glaucoma Burden through 2040: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014 Jun 26; doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013. pii: S0161-6420(14)00433-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heijl A, Bengtsson B, Oskarsdottir SE. Prevalence and severity of undetected manifest glaucoma: results from the early manifest glaucoma trial screening. Ophthalmology. 2013 Aug;120(8):1541–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malihi M, Moura Filho ER, Hodge DO, Sit AJ. Long-term trends in glaucoma-related blindness in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 2014 Jan;121(1):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marquis RE, Whitson JT. Management of glaucoma: focus on pharmacological therapy. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(1):1–21. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522010-00001. PMID: 15663346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The ocular hypertension treatment study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002 Jun;120(6):701–713. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. Discussion 829–30. PMID: 12049574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai JC, McClure CA, Ramos SE, et al. Compliance barriers in glaucoma: a systematic classification. J Glaucoma. 2003;12:393–398. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200310000-00001. PMID: 14520147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordstrom BL, Friedman DS, Mozaffari E, et al. Persistence and adherence with topical glaucoma therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Oct;140(4):598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.051. PMID: 16226511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz GF, Quigley HA. Adherence and persistence with glaucoma therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008 Nov;53(Suppl1):S57–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilensky J, Fiscella RG, Carlson AM, et al. Measurement of persistence and adherence to regimens of IOP-lowering glaucoma medications using pharmacy claims data. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006 Jan;141(1 Suppl):S28–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.09.011. PMID: 16389058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman DS, Quigley HA, Gelb L, et al. Using pharmacy claims data to study adherence to glaucoma medications: methodology and findings of the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study (GAPS) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007 Nov;48(11):5052–5057. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0290. PMID: 17962457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmier JK, Covert DW, Robin AL. First-year treatment patterns among new initiators of topical prostaglandin analogs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:851–858. doi: 10.1185/03007990902791132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vrijens B, Urquhart J. Methods for measuring, enhancing, and accounting for medication adherence in clinical trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jun;95(6):617–626. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boland MV, Ervin AM, Friedman DS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of treatments for open-angle glaucoma: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):271–279. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook PF, Schmiege SJ, Mansberger SL, Kammer J, Fitzgerald T, Kahook MY. Predictors of Adherence to Glaucoma Treatment in a Multisite Study. Ann Behav Med. 2014 Sep 24; doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9641-8. PMID: 25248302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreer LE, Girkin C, Mansberger SL. Determinants of medication adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. J Glaucoma. 2012 Apr-May;21(4):234–240. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31821dac86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robin AL, Novack GD, Covert DW, et al. Adherence in glaucoma: objective measurements of once-daily and adjunctive medication use. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007 Oct;144(4):533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.012. PMID: 17686450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cate H, Bhattacharya D, Clark A, et al. Patterns of adherence behaviour for patients with glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 2013 Apr;27(4):545–553. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sleath B, Blalock S, Covert D, et al. The relationship between glaucoma medication adherence, eye drop technique, and visual field defect severity. Ophthalmology. 2011 Dec;118(12):2398–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleath B, Ballinger R, Covert D, Robin AL, Byrd JE, Tudor G. Self-reported prevalence and factors associated with nonadherence with glaucoma medications in veteran outpatients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009 Apr;7(2):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.04.001. PMID: 19447359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djafari F, Lesk MR, Harasymowycz PJ, et al. Determinants of adherence to glaucoma medical therapy in a long-term patient population. J Glaucoma. 2009 Mar;18(3):238–243. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181815421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vandenbroeck S, De Geest S, Dobbels F, et al. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported nonadherence with eye drop treatment: the Belgian Compliance Study in Ophthalmology (BCSO) J Glaucoma. 2011 Sep;20(7):414–421. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181f7b10e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robin AL, Covert D. Does adjunctive glaucoma therapy affect adherence to the initial primary therapy? Ophthalmology. 2005;112(5):863–868. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.026. PMID: 15878067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reardon G, Kotak S, Schwartz GF. Objective assessment of compliance and persistence among patients treated for glaucoma and ocular hypertension: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:441–463. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S23780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okeke CO, Quigley HA, Jampel HD, et al. Adherence with topical glaucoma medication monitored electronically the Travatan Dosing Aid study. Ophthalmology. 2009 Feb;116(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boland MV, Chang DS, Frazier T, et al. Electronic Monitoring to Assess Adherence With Once-Daily Glaucoma Medications and Risk Factors for Nonadherence: The Automated Dosing Reminder Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 May 15; doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fillenbaum GG, Heyman A, Williams K, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of standardized screens of cognitive impairment and dementia among elderly black and white community residents. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:651–660. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90035-n. PMID: 2370572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.2014 Poverty Guidelines. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Web site. [accessed 12/30/2014]; http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/14poverty.cfm.

- 29.Hodapp E, Parrish RK, Anderson DR. Clinical Decisions in Glaucoma. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book Inc; 1993. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sleath B, Blalock SJ, Covert D, et al. Patient race, reported problems in using glaucoma medications and adherence. ISRN Ophthalmol. 2012;(2012):902819. doi: 10.5402/2012/902819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001 Aug;23(8):1296–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80109-0. PMID: 11558866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nau DP, Steinke DT, Williams LK, et al. Adherence analysis using visual analog scale versus claims-based estimation. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1792–1797. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K264. PMID: 17925497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amico KR, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, et al. Visual analog scale of ART adherence: association with 3-day self-report and adherence barriers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:455–459. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225020.73760.c2. PMID: 16810111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badiee J, Riggs PK, Rooney AS, et al. Approaches to identifying appropriate medication adherence assessments for HIV infected individuals with comorbid bipolar disorder. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012 Jul;26(7):388–394. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0447. Epub 2012 Jun 11. PMID: 22686169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeller A, Ramseier E, Teagtmeyer A, et al. Patients’ self-reported adherence to cardiovascular medication using electronic monitors as comparators. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2037–2043. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroeder K, Fahey T, Hay AD, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive medication assessed by self-report was associated with electronic monitoring compliance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Jun;59(6):650–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.013. PMID: 16713529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi L, Liu J, Koleva Y, et al. Concordance of adherence measurement using self-reported adherence questionnaires and medication monitoring devices. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(12):1097–1107. doi: 10.2165/11537400-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sleath B, Blalock SJ, Carpenter DM, et al. Ophthalmologist-Patient Communication, Self-efficacy, and Glaucoma Medication Adherence. Ophthalmology. 2014 Dec 24; doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.001. pii: S0161-6420(14)01047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hahn SR, Friedman DS, Quigley HA, et al. Effect of patient-centered communication training on discussion and detection of nonadherence in glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2010 Jul;117(7):1339.e6–1347.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.11.026. PMID: 20207417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doró P, Benko R, Czakó A, Matuz M, Thurzó F, Soós G. Optimal recall period in assessing the adherence to antihypertensive therapy: a pilot study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011 Aug;33(4):690–695. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9529-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]