Abstract

To investigate the association of ethnicity, sex, and parental pain modeling on the evaluation of experienced and imagined painful events, 173 healthy volunteers (96 women) completed the Prior Pain Experience Questionnaire, a 79-question assessment of the intensity of painful events, and a questionnaire regarding exposure to parental pain models. Consistent with existing literature, greater ratings of experienced pain were noted among Black vs. White participants. Parental pain modeling was associated with higher imagined pain ratings, but only when the parent matched the participant’s sex. This effect was greater among White and Asian participants than Black or Hispanic participants, implying ethno-cultural effects may moderate the influence of pain modeling on the evaluation of imagined pain events. The clinical implications of these findings, as well as the predictive ability of imagined pain ratings for determining future experiences of pain, should be investigated in future studies.

Keywords: Pain, ethnicity, sex, pain models, family history

Introduction

A substantial body of research supports that notion that exposure to the pain-related behaviors of parents with chronic pain (i.e., parental pain models) may influence an individual’s pain perception. The bulk of the literature examining the influence of parental pain models consists of studies conducted with children. The results of these studies support the assertion that the presence of a parental pain model can alter an child’s pain behavior through social learning (Evans et al., 2007) and is associated with greater frequency of pain complaints, increased anxiety and depression, and impaired social development (Dura & Beck, 1988; Evans & Keenan, 2007; Evans et al., 2007; Peterson & Palermo, 2004). A smaller body of research in adult samples has demonstrated a positive correlation between exposure to a pain model and frequency of pain complaints among otherwise healthy college age participants (Edwards et al., 1985a; Koutantji et al., 1998). Additionally, studies have also shown the individuals exposed to a parental pain model as children are more likely to suffer from chronic pain in adulthood (Violon & Giurgea, 1984), especially when parenting strategies involve catastrophizing about pain complaints (Evans et al., 2006).

Ethnicity has been shown to influence pain perception. Numerous studies suggest that Black individuals rate experimental painful stimuli as more intense, unpleasant, disabling, and anxiety provoking compared to Whites (Campbell et al., 2005; Edwards et al., 2001; Koutantji et al., 1998; Sheffield et al., 2000; Woodrow et al., 1972), an effect that may be related to ethnic differences in vigilance to bodily sensations and the use of passive pain coping strategies (i.e., prayer and hoping; Campbell et al., 2005). These results from experimental studies are consistent with investigations of patients with chronic pain showing Black participants report their pain as more unpleasant and disabling than Whites, and that Blacks rely more heavily on passive coping skills (Edwards et al., 2005; Riley et al., 2002a). Studies have also demonstrated Hispanics are more likely than Whites to rely on passive coping skills (Campbell et al., 2009; Edwards et al., 2005). Studies have shown Asians report higher laboratory rated intensity for thermal stimuli as compared to whites, but demonstrate no significant difference in anxiety associated with the painful experiences (Edwards et al., 2001; Watson et al., 2005).

Another factor shown to contribute to differences in pain perception is sex. The available literature supports the notion that men and women perceive and experience pain differently (Berkley, 1997; Fillingim & Maixner, 1995; Riley et al., 1998a). Women are more likely to suffer from chronic pain conditions (Fillingim et al., 2009) and report more areas of bodily pain than men (Edwards et al., 2004; Fillingim et al., 1999). Women also exhibit greater sensitivity to static (Fillingim et al., 1999; Myers et al., 2001; Riley et al., 1998c) and dynamic (George et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2004) noxious stimuli when compared with men (for review, see Riley et al., 1998a). Our laboratory has previously reported that men and women differ in the specific types of pain events previously experienced and the intensity of these events (Stutts et al., 2009). Despite our knowledge related to sex differences in pain, critical questions remain regarding the influence of ethnicity and its interaction with sex in the evaluation of painful events. Furthermore, we are unaware of studies examining the interaction of ethnicity and sex with the presence of parental pain models on the evaluation of pain experiences. Simultaneous consideration of sex, ethnicity, and parental pain modeling in analyses allows the determination of whether these factors may interact, a possibility that cannot be investigated when these factors are studied separately. Such interactions could suggest important moderators of the effect of parental pain modeling related to ethno-cultural influences and/or sex.

Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to investigate the relationships of pain models, sex, and ethnicity on the intensity of reported pain scores. On the basis of existing literature, we hypothesized that the presence of a parental pain model would be associated with higher ratings of pain intensity for both imagined and experienced pain and asked as an empirical question whether having a parental pain model of the same sex (i.e., sex-matched) and having a parental pain model of either sex would have differing main and/or interactive effects with ethnicity and sex. We also predicted significantly higher mean pain ratings for African Americans, and asked as an empirical question how the pain ratings of Hispanic and Asian participants would compare to those of White and Black participants.

Methods

Participant Recruitment

Undergraduate students at the University of Florida were recruited by flyers posted around the college campus. Participants were healthy and without a history of chronic pain. The current report is a sub-analysis from previously published data related to sex differences in previous pain experience (see Stutts et al., 2009). Eligibility requirements included being 18 years of age or older and having the capacity to understand and answer the questionnaires and provide informed consent for participation. The University of Florida Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all participants provided informed consent. Participants then completed the electronic questionnaires.

Demographic Questionnaire

Demographic characteristics, including age, years, of education, and ethnicity, were assessed using a brief questionnaire. Participants were asked to choose the ethnic category with which they most strongly identified (White/Caucasian, Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, or Other Race/Multiple Races). Because only a small minority of participants endorsed Other Race/Multiple Races (n=4), this group was not included in subsequent analyses.

Prior Pain Experience Questionnaire (PPEQ)

The PPEQ (Stutts et al., 2009) is a 79-item assessment of the perceived pain severity of commonly experienced painful events (e.g., kidney stone, paper cut, broken limb, athletic injury, bruise, broken nose, stomach cramps, etc.). Participants rated events on a scale from 0 (pain free) to 10 (worst possible pain), indicating whether they had previously experienced each painful event. If they had not previously experienced the pain event, they were asked to rate how painful they would imagine it to be using the same scale. The number of pain types experienced by each participant was noted. The PPEQ was derived rationally by University of Florida pain researchers. Although its psychometric properties have yet to be fully characterized, exploratory factor analysis revealed the best model resulted in a single factor, consistent with its theoretical development (Stutts et al., 2009).

Family Health History Questionnaire (FHHQ)

Participants completed the FHHQ in order to assess an individual’s exposure to familial pain models. Participants reported history of various chronic pain conditions for parents and siblings, including rheumatoid arthritis, persistent and severe menstrual pain, fibromyalgia syndrome, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), arthritis or chronic joint pain, chronic back pain, chronic neck pain, chronic leg pain, chronic dental pain or facial pain, chronic headaches, and irritable bowel syndrome using a checklist. Because of the focus of the current analysis on parental pain modeling, sibling health history was not considered in analyses. Chronic fatigue syndrome, anxiety, depression, and other psychological disorders were also assessed in the FHHQ; however, these pathologies were not considered in the current analysis. University of Florida pain researchers rationally derived the FHHQ.

Statistical Approach

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Ten participants with missing data on various items, especially the FHHQ, were not included in analyses. To examine potential differences in demographic variables (age and years of education) between participant groups (i.e., sex and ethnicity), a series of 1-way ANOVAs was conducted. Where Levene’s test indicated violation of the assumption of homogeneity of variance, Welch’s F-ratio was used, followed by Dunnett’s C post-hoc comparisons.

To test hypotheses and empirical questions, a series of three-way ANOVAs were conducted. The results of Sex (2: male/female) × Ethnicity (4: White/Black/Asian/Hispanic) × Parental Pain Model (2: not present/present) ANOVAs for imagined and experienced pain ratings were compared to otherwise identical ANOVAs where the presence of any parental pain model was substituted with the presence of a sex-matched parental pain model. Significant (p < 0.05) interactions were decomposed using simple main effects analysis. Sidak’s correction was used for post-hoc tests in order to account for inflated Type I error associated with multiple comparisons. The relationship between imagined and experienced ratings was characterized using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient (r). Effect sizes are reported for all hypothesis tests approaching significance (i.e., p < 0.10; η2p, Cohen’s d, and Pearson’s r, as appropriate).

Results

Participant Characteristics and Demographics

The 173 (96 female) participants with complete data averaged 23.14 (SD 5.36) years of age and 15.79 (SD 2.01) years of education. Of the total sample, 112 (64.7%) identified as White/Caucasian, 22 (12.7%) identified as Black/African American, 22 (12.7%) identified as Asian/Pacific Islander, and 17 (9.8%) identified as Hispanic. Men, on average, were slightly older than women (MMen = 24.16 years, SD = 6.86 vs. MWomen = 22.32 years, SD = 3.58; Welch’s F1,108.72 = 4.51, p = 0.04). There was no effect of sex on years of education (p > 0.21). Post-hoc analysis of a significant effect of ethnicity on age (Welch’s F3,52.92 = 6.82, p = 0.001) suggested Hispanic participants (MHispanic=20.88 years, SD=1.36) were, as a group, significantly younger than White participants (MWhite=23.47 years, SD =5.93; p < 0.05). No other age differences between ethnicities were noted (p > 0.05). Notably, age did not correlate with imagined or experienced pain ratings (p > 0.32). No significant difference in years of education between ethnic groups was noted (p > 0.25). Across participants, mean imagined pain ratings averaged 6.52 (SD 1.16; Range: 3.21 – 9.09) and mean experienced pain ratings averaged 3.54 (SD 1.19; Range: 1.10 – 7.36). Consistent with studies indicating many chronic pain conditions are more common in women (Stutts et al., 2009), significantly more women than men reported the presence of a same-sex parental pain model (Χ2 = 15.31, p < 0.0001; 66% women vs. 36.4% men). When the presence of a parental pain model of either sex was considered, this difference did not reach significance (Χ2 = 3.07, p = 0.08; 74.5% women vs. 62.3% men). 55.4% of White, 40.9% of Black, 59% of Hispanic, and 45.5% of Asian participants reported having a same-sex parental pain model. 70.5% of White, 50% of Black, 82.3% of Hispanic, and 72.7% of Asian participants reported having a pain model of either sex. No differences in the presence of parental pain models between ethnicities were noted (p’s > .15).

No difference between sexes was detected for proportion of pain events previously experienced (p > 0.28). Characterization of a significant effect of ethnicity on proportion of pain events experienced (F3,169 = 15.77; p < 0.0001) revealed White participants reported having experienced a greater proportion of pain events than any other ethnicity (p’s < 0.003), which did not differ from one another (p > 0.15). The proportion of pain events reported as previously experienced, as well as mean experienced and imagined pain ratings, by participant group is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean percentage of pain events reported as previously experienced and mean imagined and experienced pain ratings for the total sample and by group

| Group | n | % Pain Events Experienced Mean (SD) |

Imagined Pain Ratings Mean (SD) |

Experienced Pain Ratings Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | 173 | 54.0 (11.3) | 6.48 (1.23) | 3.52 (1.20) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 77 | 52.9 (12.1) | 6.29 (1.28) | 3.62 (1.24) |

| Female | 96 | 54.8 (10.6) | 6.65 (1.18) | 3.44 (1.16) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 112 | 57.8 (9.1) | 6.54 (1.10) | 3.32 (1.04) |

| Black | 22 | 45.1 (11.9) | 6.55 (1.44) | 4.27 (1.42) |

| Asian | 22 | 49.5 (12.2) | 6.43 (1.70) | 3.98 (1.54) |

| Hispanic | 17 | 46.3 (10.8) | 6.13 (1.14) | 3.39 (0.92) |

| Any Pain Model | ||||

| Has Model | 120 | 55.4 (10.3) | 6.56 (1.21) | 3.45 (1.14) |

| No Model | 53 | 50.7 (12.6) | 6.32 (1.27) | 3.68 (1.33) |

| Same-Sex Pain Model | ||||

| Has Model | 91 | 55.8 (10.8) | 6.76 (1.07) | 3.41 (1.15) |

| No Model | 82 | 52.0 (11.6) | 6.18 (1.33) | 3.55 (1.26) |

Relationship Between Imagined and Experienced Pain

Analyses revealed a significant correlation between imagined and experienced pain ratings (r = 0.66, p < 0.0001), indicating substantial shared variance (R2 = .44) between the two measures.

Imagined Pain

Three-way ANOVA (sex × ethnicity × sex-matched pain model) on participants’ mean imagined pain ratings revealed a significant main effect of sex-matched pain model such that the endorsement of a sex-matched pain model was associated with greater imagined pain ratings (F1,157 = 5.02, p = 0.03; Cohen’s d = 0.46). A main effect of participant sex approached, but did not reach, significance (F1,157 = 2.88, p = 0.09; Cohen’s d = 0.34). Significant sex × ethnicity (F3,157 = 5.79, p = 0.006, η2p = 0.08) and ethnicity × sex-matched pain model (F3,157 = 2.84, p = 0.04; η2p = 0.05; Figure 1) interactions were also noted. Subsequent characterization of the sex × ethnicity interaction revealed no significant sex differences among White and Asian participants (p’s > 0.11), but greater imagined pain ratings for Black (p = 0.008; Cohen’s d = 1.13) and Hispanic (p = 0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.12) women than their male counterparts. Examination of the ethnicity × sex-matched pain model interaction indicated that the presence of a sex-matched parental pain model was associated with greater mean imagined pain ratings among White (p = 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.57) and Asian (p = 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.14) participants, but not Black or Hispanic individuals (p’s > 0.38). No other main effects or interactions reached significance (p’s > 0.11). This analysis is summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Imagined pain intensity scores by race and presence of a sex-matched parental pain model. White and Asian participants with sex-matched parental pain models reported greater imaged pain intensity than those without. Error bars represent standard deviation. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.001.

Table 2.

Summary of three-way ANOVA (sex × ethnicity × sex-matched pain model presence) for mean imagined pain ratings.

| Factor | df | F | p | η 2 p | Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1,157 | 2.88 | 0.09 | 0.02 | Women > Men (ns) |

| Ethnicity | 3,157 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.01 | |

| Pain Model (Sex-matched) | 1,157 | 5.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | Sex-matched Pain Model > No Sex- matched Pain Model |

| Sex × Ethnicity | 3,157 | 4.33 | 0.00 6 |

0.08 | Black Women > Black Men Hispanic Women > Hispanic Men |

| Sex × Pain Model (Sex-matched) | 1,157 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.00 | |

| Ethnicity × Pain Model (Sex- matched) |

3,157 | 2.84 | 0.04 | 0.05 | White w/ Sex-matched Pain Model > White w/o Sex-matched Pain Model Asian w/ Sex-matched Pain Model > Asian w/o Sex-matched Pain Model |

| Sex × Ethnicity × Pain Model (Sex- matched) |

3,157 | 2.01 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

Follow-up comparisons are significant (p < 0.05) unless otherwise noted (ns).

A substantially different pattern of results was observed when parental pain models were not sex-matched to the participant. Although similar effects of sex (F1,157 = 3.28, p = 0.07) and sex × ethnicity (F3,157 = 2.69, p = 0.05) were noted, no other significant main effects or interactions were present (p’s > 0.43).

Experienced Pain

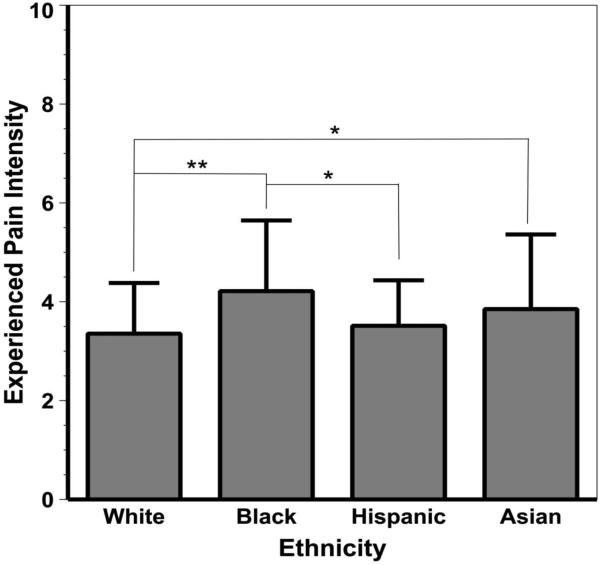

Whether pain models were sex-matched had no effect on the pattern of results for mean experienced pain ratings. In both cases, no effects of sex (p > 0.64) or presence of a parental pain model were noted (p > 0.79). Similarly, presence of parental pain models did not interact with sex (p > 0.15) or ethnicity (p > 0.21). The 3-way interaction was also not significant (p > 0.29). However, a significant main effect of ethnicity (F3,157 = 3.66, p = 0.01; η2p = 0.07) was noted such that White participants reported significantly lower experienced pain ratings than Black (p = <0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.70) and Asian (p = 0.01; Cohen’s d = 0.34) participants. Black participants also reported greater experienced pain ratings than Hispanic participants (p = 0.02; Cohen’s d = 0.63). No other differences between ethnicities were noted (p’s > 0.11). Simple main effects analysis of a significant ethnicity × sex interaction (F3,157 = 3.37, p = 0.02; η2p = 0.06) revealed a pattern of non-significant sex differences of differing directionality among ethnicities. For White (p = 0.09; Cohen’s d = 0.36) and Asian (p = 0.09; Cohen’s d = 0.56) participants, women reported lower mean experienced pain than men. In contrast, Black (p > 0.08; Cohen’s d = 0.66) and Hispanic (p > 0.17) women reported greater mean experienced pain than their male counterparts. This analysis is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of three-way ANOVA (sex × ethnicity × sex-matched pain model presence) for mean experienced pain ratings.

| Factor | df | F | p | η 2 p | Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1,157 | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.00 | |

| Ethnicity | 3,157 | 3.66 | 0.01 | 0.07 | Asian and Black > White Black > Hispanic |

| Pain Model (Sex-matched) | 1,157 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.00 | |

| Sex × Ethnicity | 3,157 | 3.37 | 0.02 | 0.06 | White and Asian Men > White and Asian Women (ns) Black and Hispanic Men < Black and Hispanic Women (ns) |

| Sex × Pain Model (Sex-matched) | 1,157 | 2.00 | 0.16 | 0.01 | |

| Ethnicity × Pain Model (Sex- matched) |

3,157 | 1.51 | 0.21 | 0.03 | |

| Sex × Ethnicity × Pain Model (Sex- matched) |

3,157 | 1.25 | 0.30 | 0.02 |

Follow-up comparisons are significant (p < 0.05) unless otherwise noted (ns).

Discussion

Results revealed the presence of a sex-matched parental pain model was associated with higher ratings of imagined events. These participants may have rated pain intensity for imagined events higher because of their parental models’ displays of pain behaviors, disability, and related psychological sequelae (e.g., catastrophizing, fear avoidance behaviors, etc.). Our data indicate that the presence of familial pain models only influenced participants’ rated intensity of imagined pain events when the pain model was sex-matched with the participant. The existing literature has focused largely on the influence of maternal pain models (Berkley, 1997), or to a lesser extent includes pain models of both sexes (Evans et al., 2007). However, we are unaware of other investigations of the influence of sex-matched parental pain models on the evaluation of painful events in healthy adult offspring.

While the mechanism underlying this effect cannot be elucidated from the current study, it is possible that sex-matched pain models may have a stronger influence on the evaluation of imagined pain events than non-matched models due to greater identification of offspring with their sex-matched parent. This possibility should be directly investigated in future studies. Interestingly, participant ethnicity appeared to moderate the effect of sex-matched pain models on imagined pain ratings, with White and Asian participants with sex-matched pain models having significantly higher ratings of imagined pain than participants of their same ethnicities without such pain models. No such effect was noted for Black and Hispanic participants. We speculate that cultural differences between ethnicities with regard to child-parent interactions may drive this effect, although replication and dissection of this effect in future studies is needed. We also found that ethnicity moderated the effect of sex on imagined pain ratings. No statistically significant differences were observed between men and women who were Asian or White; however, statistically large differences were noted between men and women who were Black or Hispanic, with women having greater ratings than men. Taken together, these results suggest ethno-cultural influences on the effects of parental pain modeling and sex on the evaluation of imagined pain events, and that these factors should be accounted for in future research regarding pain modeling and sex effects. Ethno-cultural constructs are not exclusively first-order biological constructs. Likewise, sex (i.e., being ‘male’ or ‘female’) is also confounded by social constructions (gender). Future research should attempt to disentangle the social, stereotypical, and biological influences of ethnicity, sex, and their interactions on evaluation of pain.

Finally, consistent with existing laboratory and clinical studies (Edwards et al., 1985b; Evans & Keenan, 2007), small-to-moderate ethnic differences in pain ratings for previously experienced events were noted such that White participants reported lower experienced pain ratings than Black participants. Although the current study does not provide evidence regarding a mechanism underlying these effects, ethnic differences may be attributed to a) social and cultural influences on coping style (i.e., passive versus active); b) how pain is expressed, remembered, or reported; c) differences in biological factors underlying pain processing and modulation (Rahim-Williams et al., 2012; Riley et al., 2002b). Although a main effect of sex was not noted, decomposition of a sex by ethnicity interaction for experienced pain revealed a pattern of non-significant sex differences among ethnicities (likely due to insufficient power for follow-up pairwise comparisons), with White and Asian women reporting lower experienced pain than their male counterparts. The opposite pattern was noted for Black and Hispanic participants.

Limitations

While indicative of a potentially important influence of same-sex parental pain models on the evaluation of imagined pain events, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. This study was conducted on healthy, young adults; therefore, the findings may not extend to older populations and patient groups with co-morbidities. Both the PPEQ and FHHQ rely on the reporting of past events and thus may be subject to recall bias. In addition, the exploratory nature of the study implies an elevated risk for producing potentially spurious results, highlighting the need for replication and extension in future studies. Similarly, the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the study prevents firm conclusions regarding the causality or directionality of the relationship between the endorsement of same-sex parental pain models and imagined pain. It is possible, for instance, that individuals with higher imagined pain ratings were more likely to remember parental pain models.

The relatively lower number of the non-White ethnicities included may also be viewed as a limitation. However, a pattern of significant effects of ethnicity, sex, pain modeling, and their interactions were detected, suggesting the sample was sufficient to justify further investigation. Effect sizes for all effects approaching significance (i.e., p < 0.10) are reported for purposes of planning future studies where minority individuals may be oversampled. Similarly, while these data suggest that ethnicity may modulate accepted sex differences in pain experience is potentially interesting (with women experiencing greater pain than men being the common consensus), these findings should not be over-interpreted due to the lack of statistical reliability. Future studies should seek to replicate these results using a larger sample. Finally, the psychometric properties of the PPEQ have yet to be fully explored and should be characterized in future studies. A number of significant findings consistent with both theory and previous empirical literature do show promising validity information for the measures.

Conclusions

Analyses revealed two distinct patterns of effects of sex, ethnicity, and parental pain modeling on the evaluation of experienced and imagined pain events. Findings suggesting a greater influence of sex-matched pain models on the subsequent pain behaviors of offspring have important implications for social learning influences on pain. The lack of an influence of sex-matched parental pain modeling on ratings of experienced pain events is the current analysis is intriguing. We speculate that this differential effect may reflect a particular effect of sex-matched parental modeling on pain-related expectations (as reflected by imagined pain ratings), as opposed to the recall of a pain event that an individual has experienced for her/himself.

It is possible that expectations of more intense pain from previously unexperienced events may contribute to fear and avoidance behaviors, resulting in poor adherence to physical therapy and painful interventional therapies, poorer recovery from injury, and a potentially greater likelihood of developing chronic pain (Campbell et al., 2005; Edwards et al., 2005; Rahim-Williams et al., 2012; Riley et al., 2002b). This possibility should be explicitly examined. Characterization of the predictive ability of imagined pain ratings for determining future experiences of pain (both clinical and experimental) is warranted, especially given their substantial correlation. Finally, future studies of sex-matched parental pain models and their interaction with ethnicity and sex should directly investigate their effects on pain expectations, pain behaviors, treatment acceptance, and outcomes.

Figure 2.

A main effect of ethnicity on experienced pain intensity scores, with Black participants reporting greater pain intensity than White and Hispanic participants. In addition, Asian participants reported greater pain intensity than White participants. Error bars represent standard deviation. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the participants of the study for their willingness to participate, and thank Dr. Meryl Alappattu for her helpful comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by the Department of Clinical and Health Psychology at the University of Florida. Dr. Boissoneault is supported by NINDS training grant T32NS045551 to the University of Florida Pain Research and Intervention Center of Excellence. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- Berkley KJ. Sex differences in pain. Behav Brain Sci. 1997;20(3):371–380. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x97221485. discussion 435-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain. 2005;113(1-2):20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.013. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LC, Andrews N, Scipio C, Flores B, Feliu MH, Keefe FJ. Pain coping in Latino populations. J Pain. 2009;10(10):1012–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.03.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dura JR, Beck SJ. A comparison of family functioning when mothers have chronic pain. Pain. 1988;35(1):79–89. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CL, Fillingim RB, Keefe F. Race, ethnicity and pain. Pain. 2001;94(2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards PW, O'Neill GW, Zeichner A, Kuczmierczyk AR. Effects of familial pain models on pain complaints and coping strategies. Percept Mot Skills. 1985a;61:1053–1054. doi: 10.2466/pms.1985.61.3f.1053. 3 Pt 2. doi: 10.2466/pms.1985.61.3f.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards PW, Zeichner A, Kuczmierczyk AR, Boczkowski J. Familial pain models: the relationship between family history of pain and current pain experience. Pain. 1985b;21(4):379–384. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Sullivan MJ, Fillingim RB. Catastrophizing as a mediator of sex differences in pain: differential effects for daily pain versus laboratory-induced pain. Pain. 2004;111(3):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.012. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.012 S0304-3959(04)00339-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Moric M, Husfeldt B, Buvanendran A, Ivankovich O. Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: a comparison of african american, Hispanic, and white patients. Pain Med. 2005;6(1):88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05007.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Keenan TR. Parents with chronic pain: are children equally affected by fathers as mothers in pain? A pilot study. J Child Health Care. 2007;11(2):143–157. doi: 10.1177/1367493507076072. doi: 10.1177/1367493507076072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Keenan TR, Shipton EA. Psychosocial adjustment and physical health of children living with maternal chronic pain. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43(4):262–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01057.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Shipton EA, Keenan T. The relationship between maternal chronic pain and child adjustment: the role of parenting as a mediator. J Pain. 2006;7(4):236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.10.010. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim R, Maixner W. Gender differences in the responses to noxious stimuli. Pain Forum. 1995;4(4):209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Edwards RR, Powell T. The relationship of sex and clinical pain to experimental pain responses. Pain. 1999;83(3):419–425. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00128-1. doi: S0304395999001281 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL., 3rd. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10(5):447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SZ, Wittmer VT, Fillingim RB, Robinson ME. Sex and pain-related psychological variables are associated with thermal pain sensitivity for patients with chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2007;8(1):2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.05.009. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutantji M, Pearce SA, Oakley DA. The relationship between gender and family history of pain with current pain experience and awareness of pain in others. Pain. 1998;77(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CD, Robinson ME, Riley JL, 3rd, Sheffield D. Sex, gender, and blood pressure: contributions to experimental pain report. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):545–550. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CC, Palermo TM. Parental reinforcement of recurrent pain: the moderating impact of child depression and anxiety on functional disability. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29(5):331–341. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL, 3rd, Williams AK, Fillingim RB. A quantitative review of ethnic group differences in experimental pain response: do biology, psychology, and culture matter? Pain Med. 2012;13(4):522–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01336.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, 3rd, Gilbert GH, Heft MW. Race/ethnic differences in health care use for orofacial pain among older adults. Pain. 2002a;100(1-2):119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Myers CD, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: a meta-analysis. Pain. 1998a;74(2-3):181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Price DD. A meta-analytic review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle. Pain. 1998c;81:225–235. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, 3rd, Wade JB, Myers CD, Sheffield D, Papas RK, Price DD. Racial/ethnic differences in the experience of chronic pain. Pain. 2002b;100(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson ME, Wise EA, Gagnon C, Fillingim RB, Price DD. Influences of gender role and anxiety on sex differences in temporal summation of pain. J Pain. 2004;5(2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.11.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield D, Biles PL, Orom H, Maixner W, Sheps DS. Race and sex differences in cutaneous pain perception. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(4):517–523. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutts LA, McCulloch RC, Chung K, Robinson ME. Sex differences in prior pain experience. J Pain. 2009;10(12):1226–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.04.016. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violon A, Giurgea D. Familial models for chronic pain. Pain. 1984;18(2):199–203. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90887-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PJ, Latif RK, Rowbotham DJ. Ethnic differences in thermal pain responses: a comparison of South Asian and White British healthy males. Pain. 2005;118(1-2):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.010. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow KM, Friedman GD, Siegelaub AB, Collen MF. Pain tolerance: differences according to age, sex and race. Psychosom Med. 1972;34(6):548–556. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]