Abstract

Previous studies reported that characteristic lens opacities were present in Alzheimer Disease (AD) patients postmortem. We therefore determined whether cataract grade or lens opacity is related to the risk of Alzheimer dementia in participants who have biomarkers that predict a high risk of developing the disease. AD biomarker status was determined by positron emission tomography-Pittsburgh compound B (PET-PiB) imaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ42. Cognitively normal participants with a clinical dementia rating of zero (CDR=0; N=40) or with slight evidence of dementia (CDR=0.5; N=2) were recruited from longitudinal studies of memory and aging at the Washington University Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. The age, sex, race, cataract type and cataract grade of all participants were recorded and an objective measure of lens light scattering was obtained for each eye using a Scheimpflug camera. Twenty-seven participants had no biomarkers of Alzheimer dementia and were CDR=0. Fifteen participants had biomarkers indicating increased risk of AD, two of which were CDR=0.5. Participants who were biomarker positive were older than those who were biomarker negative. Biomarker positive participants had more advanced cataracts and increased cortical light scattering, none of which reached statistical significance after adjustment for age. We conclude that cataract grade or lens opacity is unlikely to provide a non-invasive measure of the risk of developing Alzheimer dementia. Key Words: Lens opacity, cataract, Scheimpflug imaging, Alzheimer disease biomarkers, preclinical Alzheimer disease

Keywords: Lens opacity, cataract, Scheimpflug imaging, Alzheimer disease biomarkers, preclinical Alzheimer disease

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by the deposition of extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides and intracellular tau protein aggregates or neurofibrillary tangles. Beta amyloid is derived by proteolytic cleavage of the β-amyloid precursor protein (β-APP) with peptides ranging from 39–43 amino acid residues. Aβ has been shown at low physiologic concentrations to be neuroprotective through vasoconstrictive effects that decrease oxygen demand and facilitate cell membrane function (Suo et al., 1998). However, it is believed that accumulation of Aβ aggregates results in synaptic damage and neuronal cell death.

The human lens also undergoes degenerative changes with deposition of insoluble proteins during the formation of cataracts. Studies have shown that β-APP and Aβ are present in oxidative stress-induced cataracts in cultured animal lenses (Frederikse et al., 1996b). These findings motivated research to identify changes in lens morphology as a diagnostic marker for AD. In an analysis of lenses from nine participants who died with Alzheimer dementia, Goldstein et al. identified lens opacities and Aβ in a supranuclear distribution using slit lamp photomicroscopy, mass spectrometry, and immunohistochemical analysis (Goldstein et al., 2003). A follow-up study using similar techniques confirmed the presence of Aβ in postmortem lenses from Down’s Syndrome patients, in whom a third copy of chromosome 21 coding for β-APP often results in early-onset AD (Moncaster et al., 2010). In contrast, other studies did not detect supranuclear cataracts or Aβ deposits in lenses from clinically- and neuro-pathologically-confirmed AD participants (Ho et al., 2014; Michael et al., 2014; Michael et al., 2013).

Cataract type and location and the degree of opacification can be detected relatively easily using non-invasive techniques, suggesting that changes in the eye could be used as a screening tool to predict the future development of AD dementia or as a surrogate marker to monitor participants with existing disease. This study is unique in its use of a well-characterized living cohort of participants who have been risk stratified for development of AD dementia but who are non-symptomatic or demonstrate very mild cognitive impairment.

The supranuclear cataracts observed by Goldstein et al. are noteworthy because, if they occurred due to increased protein aggregation, the proteins involved must have been synthesized many years before death. The human lens grows at a linear rate from soon after birth until death and proteins are only synthesized in the most superficial cortical fiber cells (Augusteyn, 2007; Bassnett, 1997; Bassnett, 2002). The adult lens nucleus is comprised of the lens fiber cells that were present at the time of birth. This means that proteins in supranuclear (deep cortical) cataracts must have been synthesized in childhood or adolescence. If cataracts in this region were caused by protein aggregation, it is likely that increased protein aggregation would also be detectable in more superficial cortical fiber cells. The possibility of detecting cortical opacities and increased light scattering from protein aggregation in the lens cortex in pre-clinical AD provided the rationale for the present study.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board at Washington University in Saint Louis School of Medicine and the University’s Human Research Protection Office. Participants and their informants, individuals who know the participant well, provided informed consent. Participants were recruited by the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center of the Department of Neurology of Washington University in Saint Louis School of Medicine.

Risk-Stratification for Development of Alzheimer Dementia

All participants enrolled in this study had 1) completed PET-PiB imaging and had cerebrospinal fluid analysis within 1 year of participation and 2) had at least 1 neuropsychiatric assessment after their baseline assessment and 3) were aged 45 years or older. Participants were risk stratified for development of AD dementia based upon well-established biomarkers for brain Aβ plaque deposition and incipient Alzheimer dementia through 1) cerebrospinal fluids (CSF) analysis of Aβ42 levels and 2) positron emission tomography (PET) fibrillar Aβ binding potential. Low concentrations of CSF Aβ42 levels have been shown to have high correlation to progression to cognitive impairment in AD and presence of Aβ in neuropathology at autopsy (Blennow and Hampel, 2003; Hansson et al., 2006; Strozyk et al., 2003). Amyloid PET imaging measures binding potential of [11C] Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), a modified thioflavin dye for in vivo amyloid imaging, which is injected intravenously during a 60-minute dynamic PET scan. Regions of interest curves (ROIs) were created for regional specific time-activity curves and the slope of each curve reflected PiB binding (Further details can be viewed in (Roe et al., 2013)). Elevated levels of PiB binding have been related to the progression to clinical AD dementia (Morris et al., 2009). Nearly 100% concordance has been demonstrated between those with abnormally low CSF Aβ42 levels and elevated PiB amyloid imaging in participants who have received both tests (Shaw et al., 2009). All participants also underwent annual clinical neuropsychiatric evaluation through semistructured interviews with the participant and separately with a familiar informant. After assessment, including health history, depression inventory, mini-mental state exam, and a neurological exam, clinician judgment was operationalized through assignment of a clinical dementia rating (CDR) ranging from 0, 0.5, 1, 2 and 3, corresponding to no dementia (cognitively normal), very mild, mild, moderate and severe dementia, respectively. A CDR ≥0.5 indicates clinically significant cognitive impairment and is based on evidence of onset and progression of memory and other cognitive difficulties that represent a change from the participant’s previous exam. The use of the CDR has been demonstrated to be reliable (Burke et al., 1988).

Comparisons were made between individuals who were biomarker positive for Alzheimer disease, who were at highest risk for subsequent development of AD dementia, and those who were biomarker negative and therefore at lowest risk of developing AD. Individuals who were AD biomarker positive had CSF Aβ42 <400 pg/ml, and/or PET Aβ fibrillar imaging mean cortical binding potential >0.18 and/or CDR = 0.5. Individuals who were AD biomarker negative had CSF Aβ42 >400 pg/ml, PET Aβ fibrillar imaging mean cortical binding potential <0.18 and CDR = 0. The presence of these amyloid CSF and PET imaging cut-offs have been well-established in the neurology literature to confer greater risk for developing cognitive impairment (Mattsson et al., 2009; Roe et al., 2013; Tarawneh et al., 2011). The presence of these biomarkers therefore designates a preclinical stage of AD in an otherwise cognitively normal individual.

Clinical Exam, Anterior Segment Imaging and Scheimpflug Analysis

Participants received a comprehensive neuro-ophthalmologic evaluation by researchers masked to the individual’s AD biomarker status. Participant’s irises were pharmacologically dilated and research clinicians carefully examined the cataract morphology at the slit lamp using the LOCS III scoring system. A LOCS III score of two or greater was considered to be a cataract. Cross-sectional and retroillumination images of each lens were captured using a Nidek EAS-1000 Scheimpflug anterior segment camera (Nidek Co., Ltd., Aichi, Japan). Scheimpflug photography provides in-focus images from the anterior corneal surface to the posterior surface of the lens to objectively measure the light scattering properties of the lens (Wegener and Laser-Junga, 2009). Use of the Scheimpflug system allows quantification of the extent of lens opacification through densitometric analysis that measures backward light scattering intensity. A standardized orientation in which the slit beam passed through the center of the lens nucleus, with a standard illumination aperture, slit lamp wedge and flash intensity were used for each image. All lens images were taken at the same settings: slit beam length 10 mm, flash power 150 watt-second and at a standard angle from the temporal side of each eye. Retroillumination images were taken with one image focused on the anterior cortical layers to best detect cortical cataracts and another focused on the posterior cortex to detect posterior subcapsular cataracts.

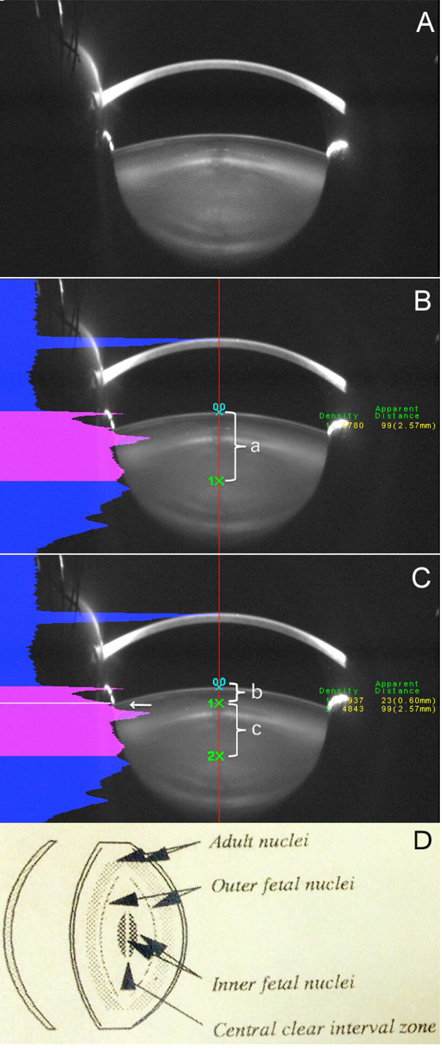

Images were analyzed with the Nidek EAS-1000 software. Image analysis utilizing linear densitometry was performed with a central axis established through the anterior-posterior optical axis of the anterior segment of the eye. The intensity plot of scattered light along the optical axis allowed delineation of the central clear zone of the lens. Lens opacity was quantified as the area under the peak of light scattering through the central line between the anterior lens capsule to the anterior cortical and nuclear area in pixel intensity units (Figure 1). The anterior lens densitometry was divided into cortical and nuclear portions by manually selecting the half-height of the anterior nuclear edge density peak (white arrow in Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Lens light scattering was detected by Scheimpflug imaging.

Figure 1A: original image. Figure 1B: Red line shown is the central lens line automatically established by the software. Points 0,0 : the anterior lens capsule; 1X: the central clear zone. a: distance between anterior lens capsule to the central clear zone, which represents anterior lens thickness. Fig 2C: The total density along the central line is shown as the pink area under the curve. The anterior lens densitometry was divided into cortical (b) and nuclear (c) parts (point 1x and white arrow) by manually selecting the half-height of the anterior nuclear edge density peak (white arrow in Fig. 1C. Fig 2D: This shows the lens layers detected by Scheimpflug imaging, including the central clear zone according to standardized grading methodologies for Scheimpflug images (Sasaki et al., 1997; Thylefors et al., 2002).

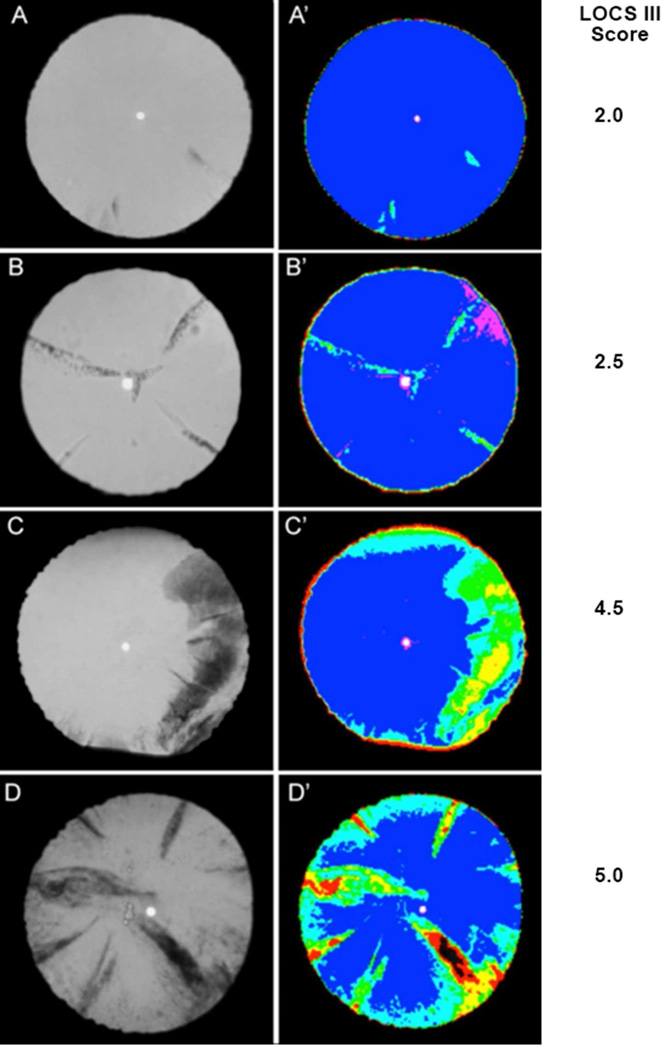

Grading of all cataracts was also performed with EAS-1000 retro-illumination images (Figure 2). Unlike traditional slit lamp photographs used for cataract grading which utilize a single plane of focus and are prone to errors from tear film disturbances, use of EAS-1000 software allowed simultaneous depth of focus throughout the entire image, enhancing nuclear density grading and adding the ability to visualize portions of cortical cataracts, which could be obscured by a poor tear film quality (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Representative EAS-1000 retroillumination images.

Areas of cortical opacification could automatically be detected with software-generated colors. Figure 2A: This shows a minor cortical opacity by retroillumination and was confirmed by software image analysis. Areas of lens opacification appear light blue versus transparent areas as deep blue. Figure 2B: The retroillumination image shows several areas of cortical opacification while 2B’ distinguishes the true opacity in light blue from the tear film in pink. Figures 2C and 2D demonstrate participants with more pronounced cortical cataracts and different degrees of cortical opacification shown as light blue, green, yellow, red to black with increasing opacification. LOCS III scores are shown to the right of the images.

The Lens Opacification Classification System III (LOCS III) was used for cataract grading by one investigator, experienced with the use of this grading system (YBS) (Chylack et al., 1989). In order to avoid bias and reduce subjectivity, EAS images were included for the nuclear cataract grading. Since EAS images were only in black and white, all LOCS III nuclear cataract grading used the classification of nuclear opalescence (NO). For the cortical cataract grading, EAS retroillumination photographs were used in this study because they allowed more accurate identification of the extent of opacification. A LOCS III score of 2 or greater was considered to indicate cataract.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison between AD biomarker positive and negative groups was performed using the t-test with Satterthwaite approximation for unequal variances when evaluating age (Moser et al., 1989). A Χ2 goodness of fit test was used for gender, race analysis and the number of participants with nuclear and cortical grading ≥2.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to determine if AD biomarker status was a predictor of nuclear and cortical lens density and LOCS III grade. GEE analysis is an extension of traditional linear regression techniques within a longitudinal framework where repeated measures are made within every individual (Albert, 1999; Zeger and Liang, 1992). Since an individual who has specific cataract morphology in one eye is more likely to have a similar one in the other eye, it is incorrect to count both eyes as 2 independent observations. Doing so would artificially increase the sample size and can result in biased P values and confidence intervals (Murdoch et al., 1998).

Use of GEE analysis allows increased precision of estimation derived from simultaneous consideration of both eyes by appropriately accounting for the correlation between fellow eyes rather than treating each patient’s eye as independent (Glynn and Rosner, 1992). GEE models were run using the GENMOD procedure in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) to analyze cortical and nuclear density, and LOCS III nuclear and cortical grading. Analysis was not performed on posterior subcapsular cataract grading as this cataract type was noted in only two of the participants. All GEE models were adjusted for age.

Identical analysis was performed using Mixed Effects Models to confirm accuracy. Under mixed effects methods, lens density was modelled as a function of age and biomarker status. The effect of the unmeasurable characteristics of the individual which give rise to the between eye correlation is modelled implicitly. This differs from GEE methods which models lens density as a function of age and biomarker status where the correlation between fellow eyes is modelled separately and explicitly. Both of these approaches give similar results (Murdoch et al., 1998). Random effects models were run using the MIXED procedure in SAS 9.2.

RESULTS

Of the 42 participants, 27 had no biomarkers indicating increased risk of developing Alzheimer dementia. Thirteen had positive AD biomarkers, suggesting increased risk of developing AD. However, none of these individuals had yet displayed any evidence of clinical dementia during detailed neuropsychiatric testing within the year of inclusion into the study. Two individuals had positive biomarkers and clinical dementia scores of 0.5.

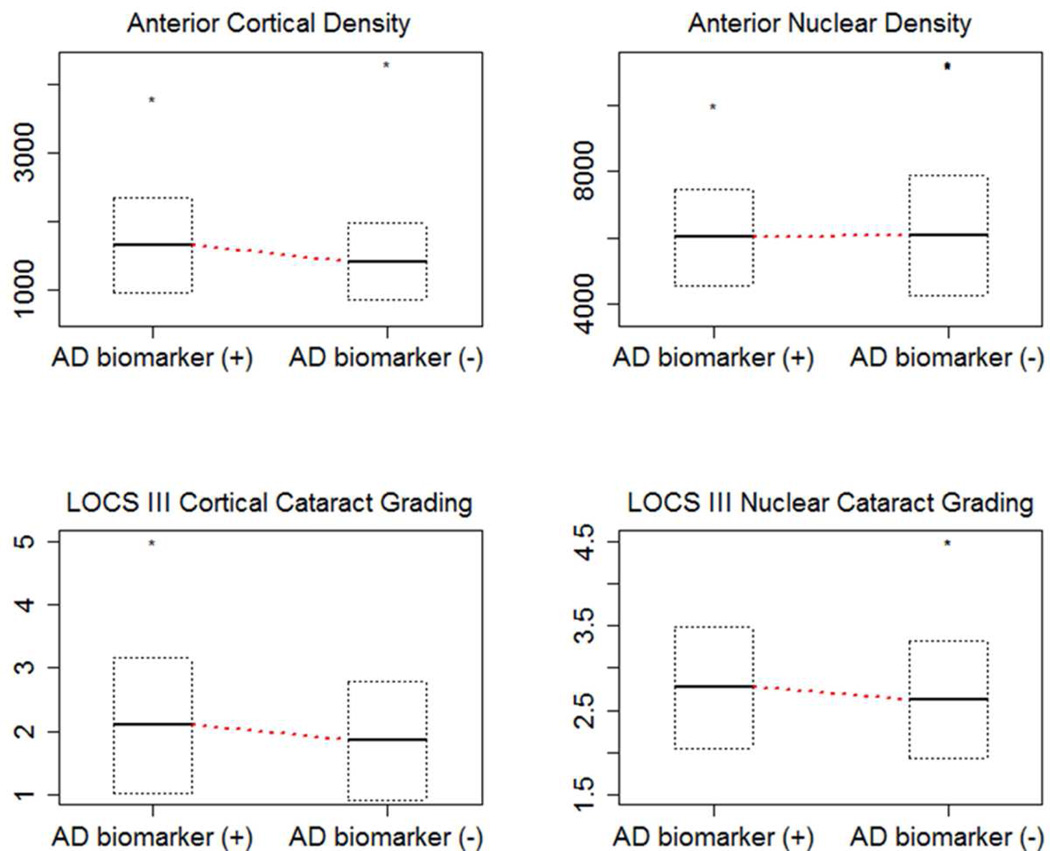

A total of 83 eyes of the 42 participants were analyzed, as 1 eye was pseudophakic. A significant difference in age was noted between the biomarker positive and negative individuals, but no significant difference in race or gender between the two groups (Table 1). All variables examined including lens density and LOCS III grading were adjusted for age in the GEE analysis. A higher proportion of biomarker positive individuals demonstrated cortical and nuclear cataracts (LOCS III score ≥2), but these differences did not reach statistical significance. There was also no significant difference between AD biomarker-positive and -negative individuals in the degree of nuclear or cortical light scattering by Scheimpflug densitometry or by LOCS III cataract grading (Table 2). No supranuclear cataracts were detected in either the AD biomarker-positive or -negative groups. All cortical cataract distributions were consistent with common age-related changes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the two groups of participants

| AD Biomarker (+) | AD Biomarker (−) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=15 | N=27 | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 77.1 ± 4.4 | 74.0 ± 4.5 | 0.003 |

| Gender (% Male) | 16.7 | 23.8 | 0.389 |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 92.6 | 86.7 | 0.397 |

| Cortical Cataract (%)* | 63.3 | 46.3 | 0.181 |

| Nuclear Cataract (%)* | 100.0 | 96.3 | 0.453 |

Cortical or nuclear cataracts are considered to be a LOCS III score ≥2.

Table 2.

Cortical density and LOCS III scores for the two groups of participants

| AD Biomarker (+) Mean ± SD |

AD biomarker (−) Mean ± SD |

GEE p-value* |

Mixed Model p-value* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Density | 1655.8 ± 693.1 | 1414.6 ± 562.8 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Nuclear Density | 6016.9 ± 1450.3 | 6086.0 ± 1816.2 | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| LOCS III Cortical Grading | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 0.66 | 0.65 |

| LOCS III Nuclear Grading | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 0.56 | 0.59 |

Adjusted for age

DISCUSSION

This study benefitted by having access to a unique group of participants who were tested for their likelihood of developing Alzheimer Disease, but had developed no dementia or only very mild dementia (N=2). Those who were “biomarker positive,” with high likelihood of developing AD, had increased binding of Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) in their brains, as determined from PET scans. PiB binds to amyloid plaques and increased binding is an indicator of advanced neurodegeneration (Morris et al., 2009). These participants also had lower levels of Aβ42 in their cerebrospinal fluid, another indicator of increased amyloid plaque formation and the subsequent development of AD (Shaw et al., 2009). Finally, all participants underwent an annual neurological exam from which they were assigned a clinical dementia rating (CDR). Except for two participants who were biomarker positive and with CDR scores of 0.5, all participants were cognitively normal (CDR=0). Therefore, the participants were divided into those with a high risk of developing AD and those with a low risk. Since most participants had a CDR of 0, their biomarker status provided a “preclinical” assessment of AD.

There is increasing evidence that structural and functional changes in the visual system, and within the eye in particular, may occur in patients with clinically significant AD (Frost et al., 2010; Tzekov and Mullan, 2014). AD patients may have an abnormal pupil response to topical ocular cholinergic or anticholinergic medications and may also show specific patterns of pupil constriction and dilation following exposure to a light flash (Fotiou et al., 2007; Idiaquez et al., 1994; Iijima et al., 2003). Retinal changes seen in AD patients include retinal nerve fiber layer loss, especially in the peripapillary and macular distribution, which can be detected using ocular coherence tomography (Paquet et al., 2007). Retinal cell layer thinning appears to correspond to functional changes detected by electroretinogram studies (Katz et al., 1989; Parisi et al., 2001).

Lens opacity as a biomarker for Alzheimer Disease was suggested by Goldstein et al. after observing deep cortical (supranuclear) cataracts in the lenses of subjects who died from AD (Goldstein et al., 2003). This study and subsequent analysis by Moncaster et al. detected beta-amyloid in lenses of patients with Down Syndrome using immunohistochemistry and mass spectrometry (Goldstein et al., 2003; Moncaster et al., 2010). However, other studies of postmortem human lenses did not detect a difference in the type and location of cataract between postmortem AD participants and dementia-free controls and found no staining in lenses from AD patients with thioflavin, Congo red or antibodies to Aβ (Ho et al., 2014; Michael et al., 2014; Michael et al., 2013).

Aβ has been found in the lenses of rats, monkeys and transgenic mice that express a copy of the human amyloid precursor protein (Tian et al., 2014). The APP over-expressing transgenic mice have increased lens opacification and pathological membrane morphology when compared to wild type mice (Melov et al., 2005). When cultured intact lenses from rats or rhesus monkeys were exposed to oxidative stress, increased levels of APP and Aβ were found in cortical fiber cells (Frederikse et al., 1996a). Microscopic examination showed changes in lens fiber membrane shape with misalignment of fiber cells and irregular fiber arrangements in whorls outside of the fetal nucleus. However, this cataract phenotype was variable in severity, onset and even between the two eyes of the same transgenic mouse (Frederikse and Ren, 2002). A recent human epidemiologic cohort study found a significant correlation between cortical cataract density, later MRI findings of structural brain degeneration and poor function on cognitive testing completed at the time of brain imaging. Use of the same cohort in a genome-wide association study identified single nucleotide polymorphisms in δ-catenin, a gene coding for a cell-junction protein, as a possible link between Alzheimer disease and cataract formation (Jun et al., 2012).

The possible overlap of Aβ pathology in the lens and in the brain suggests that changes in lens opacity could act as a simple diagnostic marker for Alzheimer Disease, particularly in the non-symptomatic, pre-clinical disease phase. This study is unique in its focus on characterizing lens morphology and an objective measure of lens opacity as diagnostic markers in a well-defined population with a pre-determined higher risk of Alzheimer dementia but with no or very mild clinical dementia. By recruiting a longitudinally followed cohort with amyloid PET imaging and CSF markers, well-accepted in the literature to be predictive of cognitive impairment (Morris et al., 2009; Shaw et al., 2009), we examined the feasibility of using lens changes as a marker of increased risk for Alzheimer dementia. This study was also able to objectively measure changes in lens opacity using Scheimpflug anterior segment imaging which has been shown be highly reproducible and correlates with standardized cataract grading systems (Kirkwood et al., 2009; Magno et al., 1994). The fact that we did not detect any significant difference in cataract type or extent of opacity in biomarker-positive or -negative participants suggests that increased lens protein aggregation in AD, if it exists, is not detectable in the earliest, pre-clinical stage of the disease, the time at which it would be most useful for diagnosis. The absence of supranuclear cataracts in this study parallels an ongoing debate about whether Aβ is confirmed in human lens tissue and whether supranuclear cataracts are specific to patients with AD (Ho et al., 2014b; Michael et al., 2014a; Michael et al., 2013).

The small differences in cortical opacity and LOCS III score for cortical cataracts could be influenced by the greater patient age in the biomarker-positive group, since both values tend to increase with age. One limitation of this study is its relatively small sample size. Increasing the number of participants could result in a significant difference in LOCS III score or cortical opacity value for the biomarker-positive participants, although these findings would be unlikely to provide sufficient sensitivity or specificity for use in the preclinical diagnosis of AD.

Figure 3. Comparison of AD biomarker positive and negative cortical and nuclear density in pixel intensity units by Scheimpflug analysis and LOCS III grading.

Horizontal lines in the box plots indicate the mean and the box represents the standard deviation.

Highlights.

This study used a unique group of participants with biomarkers that predicted their risk of developing Alzheimer Disease (AD)

Lens opacity were graded by the LOCS III scoring system and by measuring backscattered light with a Scheimpflug camera

No significant difference was detected between those at risk of developing AD (biomarker +) and those who were biomarker negative

Lens opacity is unlikely to provide a sufficiently sensitive prediction of those at risk for developing AD

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by pilot grant 29.1 from NIH grant P50 AG05681 to the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University. Participant testing was also supported by NIH grant P01 AG03991. Support was also provided by unrestricted funding to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Albert PS. Longitudinal data analysis (repeated measures) in clinical trials. Statistics in medicine. 1999;18:1707–1732. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990715)18:13<1707::aid-sim138>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augusteyn RC. Growth of the human eye lens. Molecular vision. 2007;13:252–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassnett S. Fiber cell denucleation in the primate lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1678–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassnett S. Lens Organelle Degradation. Experimental Eye Research. 2002;74:1–6. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, Hampel H. CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer's disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2003;2:605–613. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, Miller J, Rubin EH, et al. REliability of the washington university clinical dementia rating. Archives of Neurology. 1988;45:31–32. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520250037015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chylack LT, Leske MC, McCarthy D, Khu P, Kashiwagi T, Sperduto R. Lens opacities classification system II (LOCS II) Archives of ophthalmology. 1989;107:991–997. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020053028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotiou DF, Brozou CG, Haidich AB, Tsiptsios D, Nakou M, Kabitsi A, Giantselidis C, Fotiou F. Pupil reaction to light in Alzheimer's disease: evaluation of pupil size changes and mobility. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19:364–371. doi: 10.1007/BF03324716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederikse PH, Garland D, Zigler JS, Jr, Piatigorsky J. Oxidative stress increases production of beta-amyloid precursor protein and beta-amyloid (Abeta) in mammalian lenses, and Abeta has toxic effects on lens epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1996a;271:10169–10174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederikse PH, Garland D, Zigler JS, Piatigorsky J. Oxidative Stress Increases Production of -Amyloid Precursor Protein and -Amyloid (A) in Mammalian Lenses, and A Has Toxic Effects on Lens Epithelial Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996b;271:10169–10174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederikse PH, Ren XO. Lens defects and age-related fiber cell degeneration in a mouse model of increased AbetaPP gene dosage in Down syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1985–1990. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost S, Martins RN, Kanagasingam Y. Ocular biomarkers for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:1–16. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn RJ, Rosner B. Accounting for the correlation between fellow eyes in regression analysis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:381–387. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080150079033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LE, Muffat JA, Cherny RA, Moir RD, Ericsson MH, Huang X, Mavros C, Coccia JA, Faget KY, Fitch KA, Masters CL, Tanzi RE, Chylack LT, Bush AI. Cytosolic β-amyloid deposition and supranuclear cataracts in lenses from people with Alzheimer's disease. The Lancet. 2003;361:1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12981-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Londos E, Blennow K, Minthon L. Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer's disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5:228–234. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C-Y, Troncoso JC, Knox D, Stark W, Eberhart CG. Beta-Amyloid, Phospho-Tau and Alpha-Synuclein Deposits Similar to Those in the Brain Are Not Identified in the Eyes of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Disease Patients. Brain Pathology. 2014a;24:25–32. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idiaquez J, Alvarez G, Villagra R, San Martin RA. Cholinergic supersensitivity of the iris in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1544–1545. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.12.1544-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima A, Haida M, Ishikawa N, Ueno A, Minamitani H, Shinohara Y. Re-evaluation of tropicamide in the pupillary response test for Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:789–796. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun G, Moncaster JA, Koutras C, Seshadri S, Buros J, McKee AC, Levesque G, Wolf PA, St George-Hyslop P, Goldstein LE, Farrer LA. delta-Catenin is genetically and biologically associated with cortical cataract and future Alzheimer-related structural and functional brain changes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Rimmer S, Iragui V, Katzman R. Abnormal pattern electroretinogram in Alzheimer's disease: Evidence for retinal ganglion cell degeneration? Annals of Neurology. 1989;26:221–225. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood BJ, Hendicott PL, Read SA, Pesudovs K. Repeatability and validity of lens densitometry measured with Scheimpflug imaging. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:1210–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magno BV, Freidlin V, Datiles MB., 3rd Reproducibility of the NEI Scheimpflug Cataract Imaging System. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3078–3084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Hansson O, Andreasen N, Parnetti L, Jonsson M, Herukka SK, van der Flier WM, Blankenstein MA, Ewers M, Rich K, Kaiser E, Verbeek M, Tsolaki M, Mulugeta E, Rosen E, Aarsland D, Visser PJ, Schroder J, Marcusson J, de Leon M, Hampel H, Scheltens P, Pirttila T, Wallin A, Jonhagen ME, Minthon L, Winblad B, Blennow K. CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2009;302:385–393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S, Wolf N, Strozyk D, Doctrow SR, Bush AI. Mice transgenic for Alzheimer disease beta-amyloid develop lens cataracts that are rescued by antioxidant treatment. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:258–261. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael R, Otto C, Lenferink A, Gelpi E, Montenegro GA, Rosandić J, Tresserra F, Barraquer RI, Vrensen GFJM. Absence of amyloid-beta in lenses of Alzheimer patients: A confocal Raman microspectroscopic study. Experimental Eye Research. 2014b;119:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael R, Rosandic J, Montenegro GA, Lobato E, Tresserra F, Barraquer RI, Vrensen GF. Absence of beta-amyloid in cortical cataracts of donors with and without Alzheimer's disease. Exp Eye Res. 2013;106:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncaster JA, Pineda R, Moir RD, Lu S, Burton MA, Ghosh JG, Ericsson M, Soscia SJ, Mocofanescu A, Folkerth RD, Robb RM, Kuszak JR, Clark JI, Tanzi RE, Hunter DG, Goldstein LE. Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta links lens and brain pathology in Down syndrome. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser BK, Stevens GR, Watts CL. The two-sample t test versus Satterthwaite's approximate F test. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods. 1989;18:3963–3975. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch IE, Morris SS, Cousens SN. People and eyes: statistical approaches in ophthalmology. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:971–973. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.8.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquet C, Boissonnot M, Roger F, Dighiero P, Gil R, Hugon J. Abnormal retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420:97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi V, Restuccia R, Fattapposta F, Mina C, Bucci MG, Pierelli F. Morphological and functional retinal impairment in Alzheimer's disease patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1860–1867. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe CM, Fagan AM, Grant EA, Hassenstab J, Moulder KL, Maue Dreyfus D, Sutphen CL, Benzinger TLS, Mintun MA, Holtzman DM, Morris JC. Amyloid imaging and CSF biomarkers in predicting cognitive impairment up to 7.5 years later. Neurology. 2013;80:1784–1791. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918ca6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K, Sakamoto Y, Fujisawa K, Kojima M, Shibata T. A new grading system for nuclear cataracts--an alternative to the Japanese Cooperative Cataract Epidemiology Study Group's grading system. Dev Ophthalmol. 1997;27:42–49. doi: 10.1159/000425648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, Dean R, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:403–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strozyk D, Blennow K, White L, Launer L. CSF Aβ 42 levels correlate with amyloid-neuropathology in a population-based autopsy study. Neurology. 2003;60:652–656. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000046581.81650.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo Z, Humphrey J, Kundtz A, Sethi F, Placzek A, Crawford F, Mullan M. Soluble Alzheimers beta-amyloid constricts the cerebral vasculature in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 1998;257:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00814-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarawneh R, D'Angelo G, Macy E, Xiong C, Carter D, Cairns NJ, Fagan AM, Head D, Mintun MA, Ladenson JH, Lee JM, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Visinin-like protein-1: diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:274–285. doi: 10.1002/ana.22448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thylefors B, Chylack L, Jr, Konyama K, Sasaki K, Sperduto R, Taylor H, West4 S. A simplified cataract grading system The WHO Cataract Grading Group. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2002;9:83–95. doi: 10.1076/opep.9.2.83.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T, Zhang B, Jia Y, Li Z. Promise and challenge: the lens model as a biomarker for early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Dis Markers. 2014;2014:826503. doi: 10.1155/2014/826503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzekov R, Mullan M. Vision function abnormalities in Alzheimer disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59:414–433. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener A, Laser-Junga H. Photography of the anterior eye segment according to Scheimpflug's principle: options and limitations - a review. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37:144–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY. An overview of methods for the analysis of longitudinal data. Statistics in medicine. 1992;11:1825–1839. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]