Abstract

BACKGROUND

Renal failure is a frequent event after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Hemodynamic alterations during surgery as well as the underlying disease are the predisposing factors. We aimed to study intermittent furosemide therapy in the prevention of renal failure in patients undergoing CABG.

METHODS

In a single-blind randomized controlled trial, 123 elective CABG patients, 18-75 years, entered the study. Clearance of creatinine, urea and water were measured. Patients were randomly assigned into three groups: furosemide in prime (0.3-0.4 mg/kg); intermittent furosemide during CABG (0.2 mg/kg, if there was a decrease in urinary excretion) and control (no furosemide).

RESULTS

There was a significant change in serum urea, sodium and fluid balance in “intermittent furosemide” group; other variables did not change significantly before or after the operation. Post-operative fluid balance was significantly higher in “intermittent furosemide” group (2573 ± 205 ml) compared to control (1574.0 ± 155.0 ml) (P < 0.010); also, fluid balance was higher in “intermittent furosemide” group (2573 ± 205 ml) compared to “furosemide in prime” group (1935.0 ± 169.00 ml) (P < 0.010).

CONCLUSION

The study demonstrated no benefit from intermittent furosemide in elective CABG compared to furosemide in prime volume or even placebo.

Keywords: Renal Failure, Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting, Furosemide

Introduction

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a complex disorder, which is commonly seen in the perioperative period and in the intensive care unit (ICU). This phenomenon occurs in a variety of settings with clinical manifestations ranging from a minimal elevation in serum creatinine to anuric renal failure.1,2 It would be associated with a prolonged hospital stay and high morbidity and mortality.3 ARF after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is an important and independent risk factor of mortality and morbidity.4,5 As a result, the implications of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery are very well-known to cardiac anesthesiologists and intensivists.6-8

Recent studies have focused on the preventive strategies; which could be used for the high risk subsets for ARF.9 Moreover, it has been demonstrated that in high-risk cardiac surgical patients, post-operative furosemide infusion could not improve the clinical outcome of the patients in preventing the occurrence of ARF.10 Here, we aimed to study the possible role of early furosemide administration (as two different modes) compared with control, in the prevention of renal failure in patients undergoing elective CABG. Hence, there are some controversial issues regarding the need for more sophisticated studies to come to a final decision to define which therapeutic option is more effective.

Materials and Methods

This study was a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial; which was performed from January 2009 to November 2010, in a tertiary level, referral university hospital which is only a cardiovascular center. After institutional review board (IRB) approval, Tehran University of Medical Science, Iran, regarding ethical considerations and also, after taking informed written consent, among a total of 250 patients, after considering inclusion and exclusion criteria, 126 patients aged 40-75 entered the study; but among them, 123 could finish the study.

Inclusion criteria were:

Age 40-75

Elective CABG with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB)

Constant surgeon

Informed written consent.

Exclusion criteria were:

· Old age (> 75 years)

· Emergency and high-risk surgery

· Ischemic heart disease

· Diabetes mellitus

· Diabetic ketoacidosis

· Non-kenotic hyperosmolar diabetic coma

· ARF

· Chronic kidney disease causing serum Cr > 2 mg/dl

· Glomerulonephritis

· Hepatic failure causing liver function test failure (> 3 times than normal)

· Off-pump CABG

· Any unwanted complication in the operation period

· Re-starting CPB after weaning from bypass

· Pulmonary artery pressure > 30 before operation

· Ejection fraction < 30 (%)

· Re-operation in the post-operative period

· Congestive heart failure

· Thyroid disorders

· Acute infections

· Stroke

· Pregnancy

· Hospital admission in the recent 3 months.

Sample size calculation is discussed below. Our sampling strategy was a randomized single blind clinical trial; neither the patients nor the directly involved physicians knew who will belong to which group. For randomization of the patients, first, we prepared 126 small sized papers and divided them into three groups: 42 in each; A, B, or C; accordingly; Group A, Group B, or Group C.

All the patients were scheduled for elective CABG. The diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome was confirmed according to the criteria of American College of Cardiology.11 Renal function was assessed by calculating the clearance of creatinine, urea and water.

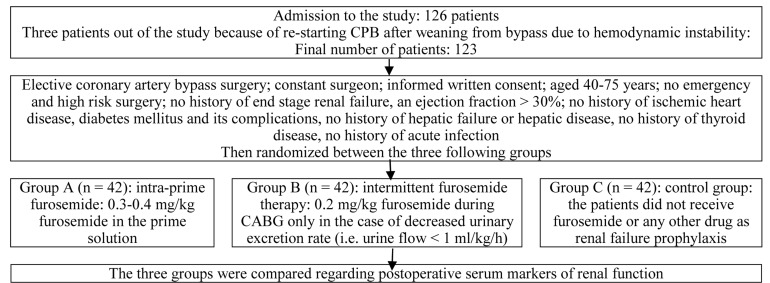

The patients were fully blinded regarding the study group in which they were allocated; also, they were randomly assigned into three groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart CPB: Cardiopulmonary bypass; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting

The first group (Group A): Intra-prime furosemide therapy was performed; i.e., these patients received 0.3-0.4 mg/kg furosemide in the prime solution; it means that furosemide was added to the CPB reservoir and when the bypass was initiated, it was mixed with patients’ blood

The second group (Group B): Intermittent furosemide therapy was done; i.e., patients received 0.2 mg/kg furosemide during CABG only in the case of decreased urinary excretion rate; the method of monitoring intra operation decrease in urinary output was exact control of hourly urinary flow by urine flow meter; if urine flow was < 1 ml/kg/h, it was considered as decreased urinary flow

The third group (Group C): i.e., the control group, the patients did not receive furosemide or any other drug as renal failure prophylaxis.

All the other therapeutic protocols were adjusted the same in the three groups. Also, we hold the diuretics before surgery.

Furthermore, those patients with the previous furosemide administration were excluded since patients who receive pre-operative furosemide may have a different response to diuretic during CABG.

The study variables were measured using one of the three following approaches:

Clinical observation (for pre-operative, intraoperative and post-operative clinical findings)

Laboratory measurements (for measuring the results of blood levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit, serum electrolytes, and serum metabolites)

Patients’ clinical files for assessing and registering their demographic and clinical data.

All the measurements for variables were done by the same person; she was blind to the patients’ group.

Blood samples were collected after almost 12 ho of fasting and, serum creatinine, lactate, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), sodium (Na) and potassium (K) were measured for all the patients before and after CABG. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault formula; which estimated the creatinine clearance rate.12 The patients did not receive any other diuretics except for furosemide during the operation. Although Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease (RIFLE) criteria have been proposed as useful criteria for staging of patients with acute kidney injuries; this criteria focuses mainly on GFR. However, the current study has used many other factors, including GFR and other criteria, including a number of electrolytes, hemoglobin, and fluid balance.

Inside the operating theater, demographic and anthropometric data including age, sex, presence of diabetes and blood pressure in sitting position were recorded. Blood pressure was measured twice after 5 min on average. Also, body mass index was calculated as kg/m2.

All patients underwent catheterization using standard Judkins or Sones techniques. Angiographic scoring was performed by 2 cardiologists. Coronary angiographies were interpreted visually and were always analyzed in 2 orthogonal views. Stenosis of > 50% in any of the main epicardial vessels reflected a significant coronary artery disease. CABG was performed according to the guidelines of American College of Cardiology.13

Sample size was determined after a power analysis (power = 0.8, β = 0.2, α = 0.02); using the power analysis and sample size software: PASS 2005 (NCSS Statistical Software, Utah, USA). The clinical criterion for sample size determination was the observed frequency of “per hour urinary output needing medical intervention;” so, we required 35 patients in each group; equals a total of 105; however, to compensate for possible dropouts, we added 20% to the calculated sample size to have a final sample of 126 (42 in each group).

The statistical package SPSS software for Windows (version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), was used for analysis. Quantitative variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Qualitative variables were presented as number and percentage. Paired sample t-test was employed for the comparison of the pre-operative and post-operative variables in each group. T-test and ANOVA were used for the comparison of the studied variables between groups.

This study has been registered in www.irct.ir, under the number: 201502122804N8.

Results

Of 126, 123 patients could finally finish the trial. Among the study population (123 patients) the majority were men: 87 (70.7%) men versus 35 (28.4%) women. The mean age of the patients was 58 ± 1.2 years. There were 39 (31.7%) patients in intra-prime furosemide group; 42 (34.1%) in intermittent furosemide therapy group and 42 (34.1%) in the control group. Basic demographic data of the participants are presented in table 1. There was no significant difference between the three groups regarding basic variables; including age (years), gender, duration of operation, ejection fraction, pre-operative serum levels of “creatinine, sodium (Na), potassium (K), lactate, GFR, BUN, hemoglobin” and also, pre-operative fluid balance (Table 1). Also, the CPB and aortic cross-clamp times were similar between the three study groups.

Table 1.

Basic variables of the study groups

| Variables | Intra-prime furosemide (Group A) (n = 42) | Intermittent furosemide therapy (Group B) (n = 42) | Control (Group C) (n = 42) | P (for ANOVA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 61.0 ± 1.4 | 62.0 ± 1.8 | 57.0 ± 2.3 | 0.147 |

| BUN | 21.4 ± 2.1 | 24.2 ± 3.3 | 19.6 ± 2.5 | 0.151 |

| Creatinine | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 0.382 |

| Hemoglobin | 15.5 ± 3.1 | 15.6 ± 3.3 | 16.3 ± 3.3 | 0.307 |

| Sodium | 142.0 ± 1.4 | 140.0 ± 1.3 | 140.0 ± 1.2 | 0.391 |

| Lactate | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.223 |

| Fluid balance (intra-operative) | 1833.0 ± 405.0 | 1379.0 ± 292.0 | 1411.0 ± 117.0 | 0.141 |

| Potassium | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 0.092 |

| GFR (ml/min) | 71.0 ± 8.3 | 58.0 ± 3.2 | 63.0 ± 3.9 | 0.079 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD; One-way ANOVA test was used for data analysis; SD: Standard deviation; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; GFR: Glomerular filtration rate

During the post-operative period, the patients were transferred to the cardiac ICU; meanwhile, significant changes in fluid balance, serum levels of BUN and serum levels of sodium (Na) were seen in Group A (P value for ANOVA < 0.010); while there was no significant difference regarding other variables before and after the operation. However, there was a significant positive fluid balance during the early post-operative period in Group B (2573 ± 205 ml) compared to Group C (1574.0 ± 155.0) and Group A (1935.0 ± 169.00); (P value for ANOVA < 0.010).

Also, after performing ANOVA test, we performed the Tukey post-hoc test; this test was done to assess, which group was different from the others in between the three groups; the group, which was different from the two others was indicated with a asterix (*) in table 2; i.e., the group differed significantly from the two other groups (P < 0.050).

Table 2.

Pre-operative and post-operative findings in three study groups

| Data variables | Intra-prime furosemide (Group A) (n = 42) | Intermittent furosemide therapy (Group B) (n = 42) | Control (Group C) (n = 42) | P for ANOVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative blood urea nitrogen | 19.4 ± 3.02 | 19.2 ± 3.3 | 19.6 ± 2.9 | 0.311 |

| Post-operative blood urea nitrogen | 16.1 ± 1.00 | 25.7 ± 3.3* | 15.8 ± 1.2 | 0.002 |

| 1st day post-operative blood urea nitrogen | 18.9 ± 1.35 | 19.9 ± 1.5 | 18.1 ± 1.1 | 0.271 |

| 2nd day post-operative blood urea nitrogen | 20.1 ± 1.50 | 28.3 ± 3.6* | 19.3 ± 1.4 | 0.001 |

| Pre-operative creatinine | 1.5 ± 0.40 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.132 |

| Post-operative creatinine | 1.2 ± 0.10 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.320 |

| 1st day post-operative creatinine | 1.2 ± 0.10 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.211 |

| 2nd day post-operative creatinine | 1.2 ± 0.10 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.103 |

| Pre-operative hemoglobin | 14.5 ± 1.20 | 14.9 ± 1.4 | 14.3 ± 1.3 | 0.111 |

| Post-operative hemoglobin | 10.3 ± 1.30 | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 9.9 ± 1.2 | 0.101 |

| 1st day post-operative hemoglobin | 9.1 ± 1.10 | 9.4 ± 1.2 | 9.1 ± 1.1 | 0.171 |

| 2nd day post-operative hemoglobin | 9.3 ± 1.20 | 9.7 ± 1.1 | 9.7 ± 1.3 | 0.262 |

| Pre-operative sodium | 142.0 ± 1.50 | 140.0 ± 1.6 | 140.0 ± 1.6 | 0.251 |

| Post-operative sodium | 136.0 ± 1.40 | 148.0 ± 3.2* | 139.0 ± 1.1 | 0.004 |

| 1st day post-operative sodium | 140.0 ± 1.00 | 148.0 ± 0.8* | 141.0 ± 1.0 | 0.002 |

| 2nd day post-operative sodium | 142.0 ± 1.90 | 148.0 ± 1.4* | 139.0 ± 1.0 | 0.001 |

| Pre-operative lactate level | 1.9 ± 1.150 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 0.320 |

| Intra-operative lactate | 4.0 ± 1.40 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 0.162 |

| Pre-operative fluid balance | 1333.0 ± 405.00 | 1379.0 ± 392.0 | 1411.0 ± 417.0 | 0.120 |

| Postoperative fluid balance | 1908.0 ± 381.00 | 2514.0 ± 662.0* | 1717.0 ± 295.0 | 0.003 |

| Post-operative fluid balance in first day of ICU | 2798.0 ± 194.00 | 2849.0 ± 171.0 | 2717.0 ± 150.0 | 0.114 |

| Post-operative fluid balance in second day of ICU | 1935.0 ± 169.00 | 2573.0 ± 205.0* | 1574.0 ± 155.0 | 0.005 |

| Intra-operative urine output | 543.0 ± 280.00 | 583.0 ± 246.0 | 550.0 ± 296.0 | 0.211 |

| Post-operative urine output | 298.0 ± 23.00 | 280.0 ± 29.0 | 298.0 ± 27.0 | 0.130 |

| Preoperative glomerular filtration rate | 71.5 ± 4.30 | 58.0 ± 3.8 | 63.0 ± 3.9 | 0.120 |

| Post-operative glomerular filtration rate | 70.6 ± 3.70 | 59.5 ± 4.1 | 65.6 ± 3.9 | 0.121 |

| Preoperative potassium | 4.2 ± 1.00 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 0.222 |

| Postoperative potassium | 4.4 ± 1.00 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 0.271 |

| First day post op potassium | 4.2 ± 1.00 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 0.232 |

| Second day post-operative potassium | 4.2 ± 1.00 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 0.221 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD; There was no difference within the two other groups, one-way ANOVA test was used for data analysis;

The results of this test demonstrated that the group indicated by asterix (*) differed significantly from the two other groups (P < 0.050);

SD: Standard deviation; ICU: Intensive care unit

Discussion

This study demonstrated that intermittent furosemide therapy does not significantly improve the renal outcome of the patients undergoing elective CABG compared with the patients receiving either an intra-prime dose or the patients in the control group.

However, the findings indicated that patients receiving intermittent furosemide therapy had the greatest positive fluid balance (i.e., extra fluid remaining in the body) compared to the other patient groups. The question here is why patients with positive fluid balance had decreased urine production during the operation; this finding could possibly be due to hypotension during the operation.

Besides, the patients receiving intra prime furosemide had significantly improved serum levels of BUN and Na, and also, improved fluid balance status.

Based on other studies, renal function is an important determinant of post-operative clinical outcome.14 also, ARF after cardiac surgery is a significant predictor of hospital mortality.15

On the other hand, some studies have demonstrated different independent risk factors, including old age, previous renal failure, emergency and high risk surgery, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart disease, and the need for inotropic drugs for ARF in CABG patients.6-8 ARF is also independently associated with early mortality following cardiac surgery, even after adjustment for comorbidities and post-operative complications.16

These findings are of great clinical importance. Inconsistent with our findings, many other studies have questioned the role of intermittent furosemide therapy in the prevention of ARF.17 In a recent randomized clinical trial by Mahesh et al.,10 and Faritous et al.18 furosemide-infusion did not showed any benefit in high-risk cardiac surgical patients and despite an increase in urinary output with furosemide, there was no decrease in renal injury, and no decrease in incidence of renal dysfunction. It could be concluded that the intermittent furosemide therapy, only increases urinary output and is not effective in the prevention of ARF. Moreover, we showed that in some parameters, intermittent furosemide therapy might deteriorate some of the renal function test indices in patients undergoing CABG with CPB.

Could we conclude that intermittent furosemide therapy is not effective in the prevention of ARF? We are not reaching to this final conclusion in this research; however, there are studies demonstrating that in cardiac surgery patients, perioperative furosemide administration could not reduce the patients’ need for renal replacement therapy.19,20 Hence, other studies have failed to demonstrate any benefit from administration of perioperative furosemide in patients undergoing cardiac surgery; our study demonstrated that perioperative furosemide in cardiac surgery patients has no superiority even compared with placebo.

Finally, this study demonstrated that in patients undergoing CABG with CPB, intermittent furosemide administration has no documented benefit regarding kidney protection; even, adding furosemide to the intra-prime volume or intermittent doses of furosemide administered during CPB should be regarded cautiously, especially in patients with decreased urinary output; this finding which is a novel finding from the current study may be controversial with some of the routine practice that anesthesiologists do during daily CABG cases.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is its short term follow up. However we took advantage of a relatively large sample size and the close similarity between groups in most of the potentially confounding variables. Also, we did not perform post-hoc analysis for ANOVA; so we had limitations regarding the completion of ANOVA analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the kind cooperation of physicians and nurses in cardiac surgery operating room and cardiac ICU, Shahid Rajaei Heart Center, Tehran, Iran, for their kind cooperation and support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guo HW, Chang Q, Xu JP, Song YH, Sun HS, Hu SS. Coronary artery bypass grafting for Kawasaki disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123(12):1533–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin CC, Wu MY, Tsai FC, Chu JJ, Chang YS, Haung YK, et al. Prediction of major complications after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting: the CGMH experience. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33(4):370–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigues AJ, Evora PR, Bassetto S, Alves JL, Scorzoni FA, Araujo WF, et al. Risk factors for acute renal failure after heart surgery. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2009;24(4):441–6. doi: 10.1590/s0102-76382009000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabbagh A, Rajaei S, Shamsolahrar MH. The effect of intravenous magnesium sulfate on acute postoperative bleeding in elective coronary artery bypass surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 2010;25(5):290–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferasatkish R, Dabbagh A, Alavi M, Mollasadeghi G, Hydarpur E, Moghadam AA, et al. Effect of magnesium sulfate on extubation time and acute pain in coronary artery bypass surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(10):1348–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos FO, Silveira MA, Maia RB, Monteiro MD, Martinelli R. Acute renal failure after coronary artery bypass surgery with extracorporeal circulation-incidence, risk factors, and mortality. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2004;83(2):150–4. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2004001400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlon PJ, Stafford-Smith M, White WD, Newman MF, King S, Winn MP, et al. Acute renal failure following cardiac surgery. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(5):1158–62. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.5.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abelha FJ, Botelho M, Fernandes V, Barros H. Determinants of postoperative acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2009;13(3):R79. doi: 10.1186/cc7894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangos GJ, Brown MA, Chan WY, Horton D, Trew P, Whitworth JA. Acute renal failure following cardiac surgery: incidence, outcomes and risk factors. Aust N Z J Med. 1995;25(4):284–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1995.tb01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahesh B, Yim B, Robson D, Pillai R, Ratnatunga C, Pigott D. Does furosemide prevent renal dysfunction in high-risk cardiac surgical patients? Results of a double-blinded prospective randomised trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33(3):370–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollack CV, Braunwald E. 2007 update to the ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: implications for emergency department practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(5):591–606. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terkelsen CJ, Sorensen JT, Nielsen TT. Is there any time left for primary percutaneous coronary intervention according to the 2007 updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction guidelines and the D2B alliance? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(15):1211–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanardo G, Michielon P, Paccagnella A, Rosi P, Calo M, Salandin V, et al. Acute renal failure in the patient undergoing cardiac operation. Prevalence, mortality rate, and main risk factors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107(6):1489–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Duca D, Iqbal S, Rahme E, Goldberg P, de Varennes B. Renal failure after cardiac surgery: timing of cardiac catheterization and other perioperative risk factors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84(4):1264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chertow GM, Levy EM, Hammermeister KE, Grover F, Daley J. Independent association between acute renal failure and mortality following cardiac surgery. Am J Med. 1998;104(4):343–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy EM, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI. The effect of acute renal failure on mortality. A cohort analysis. JAMA. 1996;275(19):1489–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faritous ZS, Aghdaie N, Yazdanian F, Azarfarin R, Dabbagh A. Perioperative risk factors for prolonged mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy in women undergoing coronary artery bypass graft with cardiopulmonary bypass. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5(2):167–9. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.82786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi A, Husain M, Salhiyyah K, Raja SG. Does perioperative furosemide usage reduce the need for renal replacement therapy in cardiac surgery patients? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15(4):750–5. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassnigg A, Donner E, Grubhofer G, Presterl E, Druml W, Hiesmayr M. Lack of renoprotective effects of dopamine and furosemide during cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(1):97–104. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]