Significance

Subpopulations of cells in a primary melanoma sometimes disseminate and establish metastases, which usually cause mortality. By sequencing tumor samples from patients with metastatic melanoma never subjected to targeted therapies, we were able to trace the genetic evolution of cells in the primary that seed metastases. We show that distinct cells in the primary depart multiple times in parallel to seed metastases, often after evolving from a common, parental cell subpopulation. Intriguingly, we also determine that single metastases can be founded by more than one cell population found in the primary cancer. These mechanisms show how profound genetic diversity arises naturally among multiple metastases, driving growth and drug resistance, but also indicate that certain mutations may distinguish cells destined to metastasize.

Keywords: metastasis, melanoma, genetics

Abstract

Melanoma is difficult to treat once it becomes metastatic. However, the precise ancestral relationship between primary tumors and their metastases is not well understood. We performed whole-exome sequencing of primary melanomas and multiple matched metastases from eight patients to elucidate their phylogenetic relationships. In six of eight patients, we found that genetically distinct cell populations in the primary tumor metastasized in parallel to different anatomic sites, rather than sequentially from one site to the next. In five of these six patients, the metastasizing cells had themselves arisen from a common parental subpopulation in the primary, indicating that the ability to establish metastases is a late-evolving trait. Interestingly, we discovered that individual metastases were sometimes founded by multiple cell populations of the primary that were genetically distinct. Such establishment of metastases by multiple tumor subpopulations could help explain why identical resistance variants are identified in different sites after initial response to systemic therapy. One primary tumor harbored two subclones with different oncogenic mutations in CTNNB1, which were both propagated to the same metastasis, raising the possibility that activation of wingless-type mouse mammary tumor virus integration site (WNT) signaling may be involved, as has been suggested by experimental models.

As in many other solid tumors, melanoma metastases often first present in lymph nodes in the draining area of the primary, whereas distant metastases tend to appear later (1). The conclusion that melanoma follows a linear progression from primary tumor to regional to distant metastases has supported preemptive surgical removal of regional lymph nodes with curative intent (2). However, several observations suggest that distant metastases are seeded early, contemporaneously with regional metastases. Patients who undergo resection of lymph node basins harboring metastasis do not experience a significantly extended life expectancy (3, 4). Furthermore, circulating melanoma cells were detected in the blood of 26% of patients who only have metastases detected regionally (5, 6).

Melanoma, like other cancers, arises and evolves through the accumulation of genetic alterations within tumor cells (7–9). Comparing somatic mutations in primary tumor and regional and distant metastases from the same patient can provide insight into the phylogenetic relationships between these distinct tumor cell populations and the order of metastatic dissemination (8, 10). These analyses may also establish whether cells in the primary tumor that metastasize acquired this ability to disseminate and seed other anatomic sites by a newly acquired genetic alteration, or whether metastatic colonization is simply a stochastic process of which all cells in the primary are capable but few succeed.

Using whole-exome sequencing (for discovery) and targeted sequencing (for validation), we analyzed mutation patterns of primary melanomas and two or more metastases in each of eight patients (Datasets S1–S8) to determine their phylogenetic relationships.

Results

Mutational Landscape of Metastatic Melanoma.

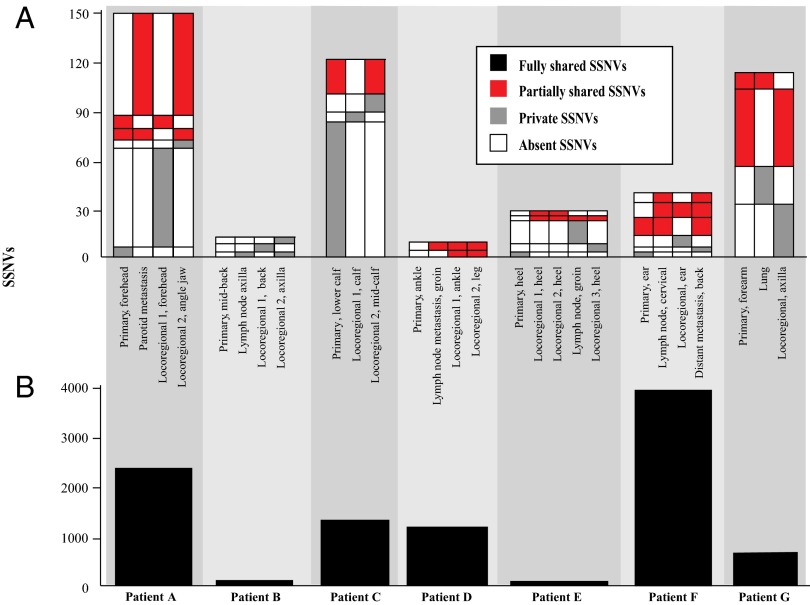

The number of somatic single nucleotide variants (SSNVs) detected varied from 96 to 115 per exome in primary melanomas from acral or intermittently exposed skin (patient E: heel, patient B: back) to more than 4,900 in primary melanomas from chronically sun-exposed sites, corresponding to 4,800–245,000 mutations per genome (seven of eight patients with high-confidence copy number estimates for all tumors are shown in Fig. 1). SSNVs detected at any allele frequency (AF) in the primary melanomas and all corresponding metastatic tissues were considered fully shared (Fig. 1, bottom black tier), including known oncogenic mutations in melanoma such as BRAFV600E (11), CTNNB1S33P (12), and in the TERT promoter (13). Fully shared variants detected at fully clonal AFs (i.e., ∼100%) in the primary were considered “ancestral”—they occurred early during population expansion of the cells comprising the primary, before any metastases had formed. In contrast, SSNVs not fully shared between primary and metastatic tumors revealed distinct evolutionary histories and are shown in the upper portion of Fig. 1 as partially shared (red) and private (gray).

Fig. 1.

Patterns of somatic mutations (SSNVs) in primary and metastases illustrate evolutionary divergence during metastatic dissemination. For the seven of eight patients also yielding high-confidence copy number estimates, the number of SSNVs in each tumor tissue is shown. (A) The number of fully shared SSNVs present in all tumors is displayed in Lower (black). (B) The number of SSNVs not present in all samples is shown in the upper column graph. The SSNVs not present in all samples are further subdivided for each sample into tiers of SSNVs: those that are partially shared with other tumors (red), those that are private to the sample (present only in one tumor of a patient, gray), and those not detected in the sample (white). Tiers with fewer than three SSNVs are not displayed. The SSNVs within each tier are listed in Dataset S3 and their interpretation is annotated in Dataset S7.

Using DNA extracted from additional tissue sections of tumors of patients A, C, E, F, and G, we validated with ion semiconductor sequencing at an average depth of 953 reads the AFs of 72 representative SSNVs originally discovered by exome sequencing. All SSNVs detected in metastases by exome sequencing were also detected by targeted sequencing. In several instances, SSNVs were only detected in some of multiple, independent tissue sections of the primary, probably reflecting tumor heterogeneity of these variants (Datasets S6 and S8).

Metastatic Dissemination Occurs in Parallel from Cell Populations in the Primary Tumor to Regional and Distant Sites.

There is controversy whether melanoma sometimes disseminates widely without an interim regional stage. If metastatic dissemination cascaded from locoregional to distant locations, one would expect regional and distant metastases to reside on a common phylogenetic branch.

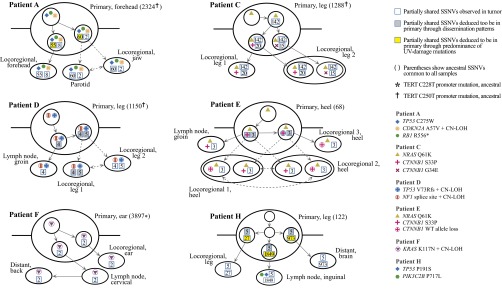

SSNVs partially shared between the primary and some, but not all metastases, revealed instances in which different subpopulations of the primary seeded independent metastases in parallel rather than in series. In these cases, cells in the primary both before and after acquisition of the partially shared variants must have established metastases. Exome sequencing in patients A, C, and F each clearly revealed two such distinct parental subpopulations in primaries shared only with some metastases (Fig. 2 and Dataset S7). Therefore, their metastases most likely arose from independent cells in the primary, rather than evolving from other metastases.

Fig. 2.

Metastases depart the primary melanoma in parallel, from genetically divergent cell subpopulations. For patients A, C, D, E, F, and H, phylogenetic history of the metastasizing cells is reconstructed based on sequencing of fresh and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) portions of each tumor (Datasets S3, S6, and S8). Solid arrows denote probable dissemination routes, and dotted arrows denote multiple possible paths. Numbers in squares denote partially shared SSNVs. Instances of SSNVs deduced to be in the primary, but not detected directly by sequencing, are color coded by line of reasoning. The patterns of dissemination demonstrate that metastases in each patient derived from distinct cells in the primary, which often demonstrate extensive genetic divergence from each other.

In patient F, validation sequencing confirmed that at least two SSNVs were present subclonally in the primary, absent in the locoregional metastasis, yet detected in the lymph node and distant skin metastasis (TBC1D1 and ABCA8; Datasets S3 and S7; class 5). Conversely, at least two SSNVs were present subclonally in the primary, absent in the lymph node and distant metastases, yet present in the locoregional tumor (ZNF165 and BPTF; Datasets S3 and S7; class 7). Thus, we can conclude that the locoregional tumor arose from a cell population in the primary distinct from the one generating the lymph node and distant metastasis.

In patient H, deletion of one copy of chromosome 4 was seen in the primary and the brain metastasis, yet absent in the lymph node and locoregional skin metastases (Dataset S5), showing that the latter tumors could not have given rise to the brain metastasis. Furthermore, the private mutations from both the lymph node and brain metastasis harbored a predominance of C > T substitutions (1725/1849 and 804/973 SSNVs, respectively), suggesting that these metastases also arose from different cells in the primary (Fig. 2). It is unlikely that these UV-driven mutations were acquired in a tumor other than the primary.

In patient D, where the primary was found in the right leg, four SSNVs were partially shared by the groin lymph node and in transit right leg locoregional metastases, and five additional SSNVs were partially shared by only the two locoregional metastases (Datasets S1 and S7). The anatomic relationship makes it unlikely that cells in the groin lymph node returned to found multiple locoregional metastases only in one foot, close to the primary. Therefore, we posit that the five partially shared SSNVs were acquired in distinct cells of the primary, some of which disseminated and formed two distinct subpopulations in the locoregional metastases.

In patient E, a cell population harboring an interstitial deletion of the wild-type copy of CTNNB1 was detected at subclonal proportions in two separate metastases (Datasets S5 and S9), strongly suggesting that they were founded by a single, undetected cell subpopulation in the primary. Overall, six of eight of our patients showed clear evidence of parallel dissemination of metastases from the primary tumor.

Metastases Can Be Founded by Multiple, Genetically Distinct Cell Populations.

Copy number aberrations (CNAs) with read counts from exome sequencing significantly below the expected threshold for full clonality were considered subclonal (14) (detailed methods in Supporting Information). Each patient had at least one tumor with such subclonal CNAs (range 1–10 per patient, with a maximum of 6 per tumor; Supporting Information and Datasets S5 and S9). Subclonal CNAs in the primary must have arisen after the lesion was founded. Any metastasis founded from cells of such a subclone should harbor that new aberration in every cell.

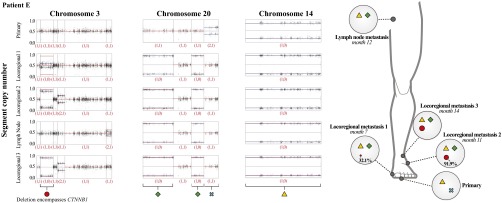

Unexpectedly, in patient E, the identical 34-Mb interstitial deletions on chromosome 3 deleting CTNNB1 were observed in both locoregional metastases 1 and 2 at subclonal levels (Fig. 3). Given the identical flanking breakpoints shared by the deletions, it is unlikely that they arose independently in these two metastases. We conclude that these metastases must each have been founded by at least two cell populations: one harboring the deletion and one without. In no other patients were we able to identify identical, unique, subclonal CNAs in more than one metastasis.

Fig. 3.

Identical subclonal deletions in different metastases reveal multiple founding populations during metastatic dissemination. The scatter graphs chart show on the y axis, for tumors of patient E, the allelic fraction of heterozygous SNPs along chromosomes 3, 20, and 14. Shown are the primary tumor, three locoregional metastases, and a lymph node metastasis, ordered from top to bottom according to time of clinical presentation. Divergence of the allelic fractions from 0.5 indicates a copy number change. The resulting allelic states are shown in the red numbers underneath each segment. The red lines depict the expected allelic fraction, if the CNA were present in all cells of the tumor, taking into account the normal cell contamination. Blue lines indicate the observed average copy number level for each CNA. The 33.9-Mb region on chromosome 3 represented by the red circle shows a subclonal deletion in locoregional metastases 1 (TVP = 32.1%, 99%CI = 28.0–35.6%) and 2 (TVP = 91.9%, 99%CI = 90.4–93.2%) and fully clonal deletion in metastasis 3 (TVP = 100%) (Supporting Information and Datasets S5 and S9). Chromosome 20 shows two separate deletions reaching from 0–25.53 Mb and from 40.39–50.93 Mb, respectively, represented by the green diamond, which are present at fully clonal levels in all metastases but absent in the primary tumor. One entire copy of chromosome 14 is deleted at fully clonal levels in all tumors and is thus considered fully shared (yellow triangle). The presence of the deletion from 9.72–43.6 Mb of chromosome 3 at subclonal levels in locoregional metastases 1 and 2 suggests at least one of these tumors was founded by two distinct cell populations: one harboring the chromosome 3 deletion and one without.

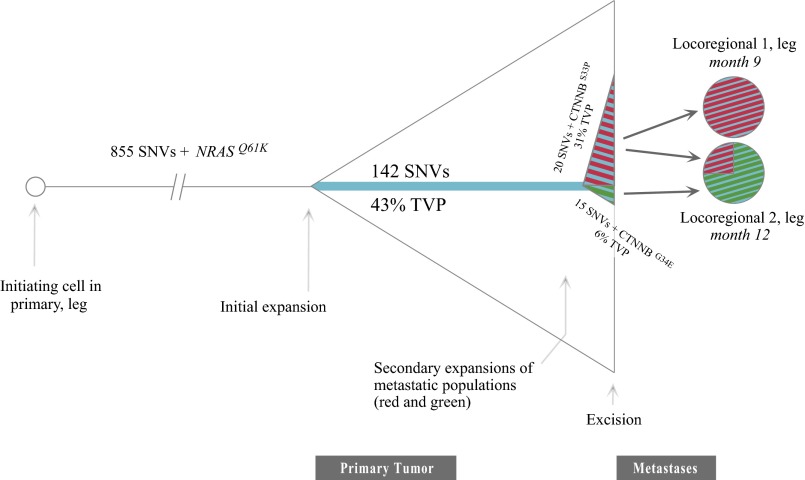

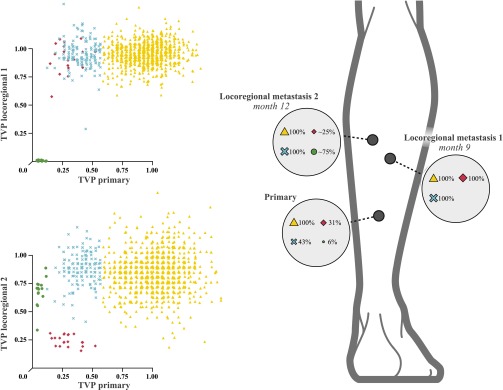

We were interested to learn if our SSNV data could also reveal multiple cell populations founding single metastases. Because individual SSNVs provide insufficient power to identify subclones definitively, we searched for clusters of partially or fully shared SSNVs with similar subclonal AFs, indicative of subpopulations. We estimated the percentage of tumor cells carrying each individual SSNV in diploid regions, taking into account the normal cell contamination and copy number at the locus harboring the SSNV. In only patient C, four such clusters of SSNVs were discerned, using a grouping algorithm, in the primary and both metastases. Each of these four clusters of SSNVs showed coordinate changes in tumor variant percentage (TVP) between the primary tumor and two metastases (Fig. 4 and Dataset S10).

Fig. 4.

Identical subclones in different metastases, as defined by SSNVs, reveal multiple founding populations during metastatic dissemination. The scatter graphs show, for patient C, the TVPs for all SSNVs in genomic regions not affected by copy number changes (Dataset S10). Shown are the TVPs for the primary tumor on the x axes and the locoregional metastases 1 (upper graph) and 2 (lower graph) on the respective y axes. Fully shared SSNVs are depicted as yellow triangles and are present in all tumors at fully clonal levels. A subclone present in ∼30% of the cells of the primary tumor (blue ×) is present at close to fully clonal levels (TVP = 100%) in both metastases. A second subclone with TVP of 25% in the primary (red diamonds) is fully clonal in metastasis 1 but at a TVP of 25% in metastasis 2, suggesting that metastasis 2 was seeded by at least two genetically distinct founding cells, one containing the SSNVs depicted as red diamonds and one without. A third subclone present at 3% in the primary melanoma, (green circles) is absent in metastasis 1 but present at ∼75% abundance in metastasis 2, indicating that it has contributed partly, but not entirely, to the cells of metastasis 2. This third subclone therefore also indicates that metastasis 2 was founded by two genetically distinct populations.

The clusters generated by this algorithm make it clear that some fully clonal SSNVs in the primary are also fully clonal in both metastases (Fig. 4, yellow triangles). Some subclonal SSNVs in the primary are fully clonal in both metastases (blue ✖’s). Two other clusters of subclonal SSNVs present in the primary at lower abundance (red diamonds and green circles) do not cosegregate in locoregional metastasis 1, indicating that each must reside in a different cell population. Surprisingly, however, both of these distinct subpopulations are detected in locoregional metastasis 2 in patient C. Therefore, the sequencing data in both patients C and E suggest that their metastases were seeded not by single cells, but by at least two cells with distinct genetic identities.

Intriguingly, in both patients, the defining subclonal populations also included alterations in CTNNB1. In patient E, the interstitial deletion on chromosome 3 removed a wild-type copy of CTNNB1, leaving a hemizygous S33P mutation. In patient C, two different known oncogenic CTNNB1 variants were detected that appeared to have arisen in distinct tumor subpopulations, evidenced by their location within distinct clusters of SSNVs (Fig. 4). The G34E variant, part of the SSNV cluster annotated with green circles, was estimated to be present in 6% of the cells in the primary, absent in locoregional metastasis 1, and present in 75% of cells in locoregional metastasis 2. By contrast, the S33P variant, in the SSNV cluster denoted by red diamonds, was present in 31% of cells in the primary, fully clonal in locoregional metastasis 1, and present in 25% of the cells of locoregional metastasis 2. Both subpopulations must have disseminated independently to locoregional metastasis 2. It is remarkable that known activating mutations in β-catenin emerged multiple times among these late-arising variants associated with metastases. Activation of the wingless-type mouse mammary tumor virus integration site (WNT) signaling pathway (e.g., by β-catenin mutations) has also been implicating in promoting metastatic potential in mouse models of melanoma (15, 16). The reconstructed evolution of metastatic dissemination in patient C is depicted in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

An integrated portrait of metastatic subclone formation, departure, and arrival for patient C. The ancestral cell harboring 855 SSNVs proliferated, generating the primary tumor. During expansion into the primary, a specific cell acquired 142 more SSNVs and then two cells from that subpopulation subsequently acquired 15 more (red) and 20 more (green) SSNVs. Intriguingly, each of these later-evolving subpopulations (red and green, identical to those seen in metastases) each acquires a different known oncogenic CTNNB1 mutation. Both subclones are seen in locoregional metastasis 2, suggesting that once the ability to metastasize is acquired, the competent subclone can either reach existing metastases or travel with other metastatic subclones simultaneously.

Metastases Are Founded by Common, Parental Cell Subpopulations in the Primary Melanoma.

As discussed above, in patients C and D, we found evidence of stepwise evolution of the metastatic subpopulations in the primary melanoma, supporting a common progenitor of metastases that arose over time in the primaries.

A distinct line of evidence supporting descent of metastatic cell populations from specific, subclonal populations in the primary is the presence of SSNVs partially shared among all metastases but not detected in the primary. In such cases, the population of cells in the primary that spawned the metastases must either have: (i) resided in the unsequenced portion, (ii) resided at undetectable (<1%) subclonal levels in the sequenced portion, or (iii) originated from a separate metastasis not analyzed in our study. Three such SSNVs were detected in patient E (class 3; Datasets S3 and S7) and five such SSNVs were detected in patient H (class 5; Datasets S3 and S7).

In patient F, four SSNVs partially shared between the primary and specific metastases were not detected in tissue representing at least 10% of the primary tumor used for exome and validation sequencing (classes 5 and 7; Dataset S8), indicating origin in a subclonal population in the remainder of the primary. Therefore, in five of six patients (C, D, E, F, and H) in whom metastases originated from at least two distinct subclonal populations in the primary, these subclonal populations themselves descended from a common, parental subclonal population.

Discussion

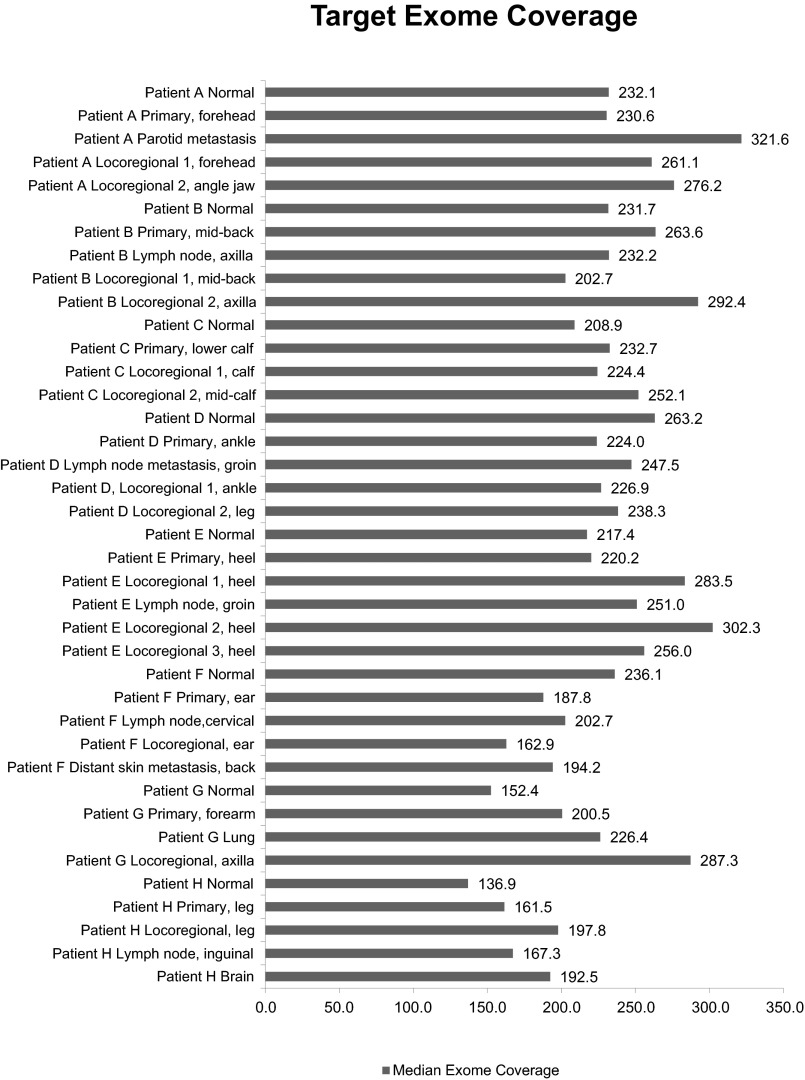

Our study reframes current models of metastatic dissemination. Although our cohort consists of only eight patients, the difficulty in collecting frozen tissues from samples of primaries and multiple metastases from patients, in the absence of systemic treatment, presents a substantial challenge to assembling larger series. Our collected materials enabled us to analyze, at high sequence coverage (Fig. S1), distinct regions of both primary melanomas and their matched metastases. The resulting data allowed us to delineate and validate the phylogenetic relationship between tumor populations at different sites. Our study provides evidence that metastatic dissemination occurs from different subpopulations of the primary tumor, which often disseminate in parallel rather than in serial fashion to form regional and distant metastases. The metastasis of genetically distinct cell populations from primary melanomas likely enhances the heterogeneity of tumor tissues, potentially contributing to drug resistance (17, 18).

Fig. S1.

Median exome sequencing coverage. On-target median fold coverage for each sample in each patient.

The sequential concept of metastatic dissemination is based on the clinical observation that regional metastases are often detected earlier than distant metastases (2). Although explanations such as secretion of growth stimulating factors from the primary have been proposed (19, 20), our observation of multiple founding populations in metastases raises the possibility that regional metastases may grow faster because their proximity to the primary increases the probability of repeated seeding events, as has been demonstrated experimentally in breast cancer (21, 22).

It is conceivable that in some cases the multiple founding populations in metastases may be the result of disseminating cell clusters, as has been detected recently in both mouse models of melanoma and in patients (23). Interestingly, the circulating clusters in breast cancer also show enhanced signaling through catenin (24), a molecule also activated in several of our metastases. The phenomenon reported here in human melanoma patients may explain certain patterns of disease relapse of patients treated with targeted therapy. For example, if multiple metastases were partially founded by a specific cell population harboring a resistance variant, these metastases may simultaneously resume growth after an initial period of response. Such a pattern has been shown for MAPK/ERK kinase mutations in a patient whose B-Raf proto-oncogene (BRAF) mutant melanoma initially responded to rapidly accelerating fibrosarcoma (RAF) inhibition but then showed striking multifocal relapse (25).

Finally, we demonstrate that the ability of cells to establish metastases can be a trait that emerges from a subclonal parent, suggesting changes are required in addition to the alterations required to establish the primary tumor. It is possible cells founding metastases repeatedly descended from a common parent simply by chance. However, in patients C and E, whose primaries harbored activating NRAS mutations, all six metastases were founded only by subclonal populations of the primary that had acquired activated CTNNB1 (Figs. 4 and 5). Beta-catenin has previously been experimentally associated with metastasis in melanoma (15, 16). Of the two cell populations metastasizing in patient C, each acquired a different, known activating mutation in beta-catenin (S33P and G34E), consistent with a necessity for CTNNB1 activation in forming metastases.

Although later evolution of metastatic cell subpopulations has been reported in some pancreatic cancers (10, 26), it was not detected in single-cell sequencing analysis of breast cancer metastasis (27). A model in which some primary melanomas require additional aberrations to metastasize may explain why their early detection and removal confers a survival benefit, as excision of tumors before the emergence of a clone with enhanced metastatic capability would be expected to be curative (28). If confirmed, these metastasis-enabling mutations could serve as biomarkers to identify primary melanomas at risk for dissemination.

Methods

Patients, Sample Preparation, and Sequencing.

Fresh frozen tissues from primary melanomas, corresponding metastases from lymph nodes, visceral sites, or skin, and matching normal DNA, were obtained from eight patients from Melanoma Institute Australia (MIA) and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) with the approval of their Institutional Review Boards. (Table S1, Dataset S1, and Supporting Information). A 5-μm-thick frozen section was cut and areas containing >80% tumor nuclei and <30% necrosis were dissected. Five micrograms of DNA from dissected tumors and matched DNA from peripheral blood were isolated. About 71 Mb of coding sequence were targeted using Agilent SureSelect Exome Capture kits with the v4 exome + untranslated region (UTR) bait library. Sequencing was performed using an Illumina HiSeq2000 instrument.

Table S1.

Histopathology of metastatic melanomas

| Source | Patient code | Anatomic site | Histopathologic detail | Tumor cell % estimate by histopathology | Tumor cell % from sequence calculation | Date of surgery/blood collection |

| Melanoma Institute Australia | A | Normal (peripheral blood) | 0 | 0 | 2/2008 | |

| Primary, forehead | Breslow 7mm; Clark level V; ulceration absent; 7 mitoses/mm2 | 70 | 76 | 9/2006 | ||

| Parotid metastasis | 70 | 21 | 12/2008 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 1 | 80 | 42 | 2/2009 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 2, angle jaw | 70 | 62 | 7/2009 | |||

| Melanoma Institute Australia | B | Normal (peripheral blood) | 0 | 0 | 7/2009 | |

| Primary, midleft back | Breslow 9 mm; Clark level IV; ulceration present; 4 mitoses/mm2 | 90 | 89 | 8/2009 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis, left axilla | 70 | 23 | 2/2010 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 1, left back | 90 | 88 | 11/2010 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 2, left axilla | 70 | 51 | 6/2011 | |||

| Melanoma Institute Australia | C | Normal (peripheral blood) | 0 | 0 | 11/2010 | |

| Primary, lower right calf | Breslow 4.94 mm; Clark level V; ulceration absent; 7mitoses/mm2 | 80 | 54 | 1/2010 | ||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 1, right calf | 90 | 85 | 10/2010 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 2, right midcalf | 70 | 54 | 1/2011 | |||

| Melanoma Institute Australia | D | Normal (peripheral blood) | 0 | 0 | 6/2010 | |

| Primary, right ankle | Breslow 5.9 mm; Clark level V, ulceration present; 5 mitoses/mm2 | 80 | 52 | 7/2010 | ||

| Lymph node, right groin | 70 | 58 | 3/2011 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 1, right ankle | 90 | 77 | 7/2011 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 2, right leg | 70 | 86 | 7/2011 | |||

| Melanoma Institute Australia | E | Normal (peripheral blood) | 0 | 0 | 11/2010 | |

| Primary, left heel | Breslow 5.5 mm; Clark level V; ulceration absent; 8 mitoses/mm2 | 80 | 80 | 11/2010 | ||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 1, left heel | 80 | 90 | 6/2011 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis 2, left heel | 70 | 90 | 10/2011 | |||

| Lymph node, left groin | 70 | 89 | 11/2011 | |||

| Locoregional metastasis 3, left heel | 80 | 89 | 1/2012 | |||

| Melanoma Institute Australia | F | Normal (peripheral blood) | 0 | 0 | 2/2011 | |

| Primary, left ear | Breslow 12 mm; Clark level V; ulceration absent; 19 mitoses/mm2 | 90 | 66 | 3/2011 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis, left cervical node | 80 | 57 | 3/2011 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis, left ear | 70 | 41 | 5/2011 | |||

| Distant skin metastasis, back | 80 | 56 | 7/2011 | |||

| Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | G | Normal skin | 0 | 0 | 10/2006 | |

| Primary, right forearm | Breslow 12mm; Clark level V; ulceration absent; 11 mitoses/mm2 | 95 tumor, 0 necrosis, 5 collagen | 62 | 10/2006 | ||

| Lung metastasis | 25 tumor, 75 necrosis | 63 | 4/2010 | |||

| Locoregional skin metastasis, axilla | 90 tumor, 10 necrosis | 92 | 3/2009 | |||

| Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | H | Normal skin (right leg) | 0 | 0 | 9/2004 | |

| Primary, right leg | Breslow 35 mm; Clark level V; ulceration present; 4 mitoses/mm2 | 90 tumor, 5 necrosis, 5 collagen; TIL++ | 51 | 1/2002 | ||

| Locoregional skin metastasis, right leg | 85 tumor, 0 necrosis, 15 skin/dermis; TIL++ | 34 | 9/2004 | |||

| Lymph node, right inguinal node | 60 tumor, 40 necrosis | 58 | 10/2004 | |||

| Brain metastasis | 90 tumor, 5 necrosis, 5 collagen | 46 | 11/2005 |

Anatomic site, histopathologic type (as called by a board-certified dermatopathologist), Breslow depth, tumor cell percent by histopathology and sequencing data, and date of first surgical excision are listed for all tumors in all patient series.

Calling Single Nucleotide and Copy Number Variants.

Somatic point mutations, referred to here as single nucleotide variants (SSNVs), were called using a standard pipeline (Supporting Information) and sample identity was verified using genotype information (Dataset S2). In brief, for each patient, any high-confidence SSNV PRESENT in at least one tumor sample was also called PRESENT in any other sample in which supporting reads were found. Copy number variants were identified from exome data using an iterative aggregation method (Supporting Information). To determine the fraction of tumor cells carrying an SSNV or CNA, a tumor variant percentage (TVP) was calculated based on estimates of normal cell contamination, mutant AF (SSNVs), copy number state, and allelic ratio of heterozygous SNPs within CNAs. To reduce stochastic error, further analysis was only performed for SSNVs with a minimum read depth of 42, which on average supported a TVP with 99% confidence interval (CI) < 1 across study patients. If three or more such SSNVs displayed identical PRESENT/ABSENT patterns across samples in a patient, they were classified for closer inspection (Datasets S3 and S7). For CNAs, multiple sources of data bias were identified and corrected for before calculation of both a TVP and a 99% CI where data were sufficient (Datasets S5 and S9 and Supporting Information).

Study Design and Tumor Samples

Tumor samples were obtained from (i) the Melanoma Institute Australia Biospecimen Bank, a prospective collection of fresh-frozen tumors accrued with informed consent and IRB approval since 1996 through MIA (formerly the Sydney Melanoma Unit); and (ii) the Tumor Procurement Service of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), a biospecimen collection of fresh-frozen tumors acquired and managed in accordance with requirements stipulated by the Institutional Review Board and the Human Biospecimen Utilization Committee of MSKCC. Tumors were included from patients for whom primary melanomas and two or more metastases were available. No samples were excluded during the course of the study. There were no additional exclusion criteria.

The patients with lymph node metastases at time of initial presentation and staging were B, D, E, and F. Where multiple positive lymph nodes were detected, only one was taken for sequencing. These patients were profiled before the advent of targeted therapeutics and were not given interferon or any systemic chemotherapies before the tumors were banked.

Banked fresh-frozen tumor metastasis samples selected for analysis were reviewed by a pathologist and scored for the percentage of tumor cells present and necrosis. Linked pathologic data were obtained for number of nodes involved, largest metastasis size and presence of extranodal spread.

DNA Isolation and Sequencing

At least 5 µg of DNA from dissected tissue and matching DNA from peripheral blood were extracted using the DNeasy kit (Qiagen) and the Flexigene kit (Qiagen), respectively. For sequencing, ∼1.0 µg genomic DNA from tumor and normal tissue was sheared by sonication to an average length of 150 bp on a Covaris E220 acoustic sonicator. About 71 megabases of coding sequence and untranslated regions were targeted using oligonucleotide-based hybrid capture using Agilent SureSelect Exome Capture kits with the v4 exome + UTR bait library. Sequencing-by-synthesis using the Illumina HiSeq2000 systems resulted in more than 85% of targeted regions receiving 150×-fold coverage at >90% of bases (Dataset S2).

SSNV Calling

Raw sequencing data in Illumina's fastq data format was converted into fastq files with base quality scores encoded in the Sanger basecall format. Next, the reads were aligned using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (29). This aligner is based on the Burrows–Wheeler transformation, aligns paired-end reads and handles indels robustly. The output of BWA are the aligned reads in sequence alignment/map (SAM) format. Reads stored in SAM format were then converted to the binary SAM (BAM) format using the samtools software (30). Once reads were in the sorted and indexed BAM file format, position based retrieval of reads was expedited and data storage requirements were minimized. Next, to remove erroneous mutation calls due to PCR duplication, all duplicate reads were removed using MarkDuplicates, an analysis tool included in the Picard software package developed by the Broad Institute (sourceforge.net/projects/picard/). After removal of the duplicate reads, the base quality scores were recalibrated using the CountCovariates and TableRecalibration tools included in the Genome Analysis Toolkit software, also developed by the Broad Institute (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/).

The tumor and matched normal BAM files were analyzed for single nucleotide variants with the following method. Sequenced bases with ≥8 unique (nonduplicate reads) with mapping quality ≥20 in both tumor and matched normal were used to compute the likelihoods of all possible genotypes (AA, AT, AC, etc.) using a mapping quality-based error model (29), available in the samtools source code. If fewer than two reads support any nonreference allele at the current position, then that the position was deemed homozygous reference and no further analysis was performed. The genotype likelihoods were used in a Bayesian model used by the Somatic Sniper method (31–33), incorporating a prior probability on the reference, the fraction of heterozygous positions in the human genome, the probability to convert the normal genotype to the tumor genotype. Each tumor/normal genotype pair was scored using this model. The genotype pair with the highest likelihood given the data was chosen as the most likely tumor and normal genotypes. Any position that was determined to be homozygous for the reference allele in both tumor and normal was not further analyzed.

If tumor and normal genotypes were identical, then the variant was classified as germ line. Instances where the normal genotype was heterozygous and the tumor genotype was homozygous suggest not new point mutations but regions of loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH), and such variants were so classified. For variants classified as either germ line or LOH, the log-likelihood of the paired genotype was used to compute a Phred-scaled quality/confidence of the germ-line variant. All other variants were classified as a somatic mutation and their somatic score (SS) was calculated (31).

For any position where the tumor and/or normal genotype was not homozygous for the reference allele, a number of metrics were computed, including number of total reads, number of allelic reads, average base and mapping quality, number of reads with mapping quality = 0, number and quality sum of mismatches in reads with variant or reference allele, the distance of the variant to the 3′ end of the read, and number of reads aligned to the forward/reverse strand. All putative variants and their associated metrics were converted to the variant call format (VCF) and the following filters (31) applied:

conf: Genotype quality or SS ≥ 100

dp: Total depth (DP of normal + primary) ≥ 8

mq0: # number of mapping quality = 0 reads < 5

sb: Mutant allele strand bias P value > 0.005. (Binomial test)

mmqs: quality sum of mismatches (per read) ≤ 20 (31)

amm: average number of mismatches (per read) ≤ 1.5 (31)

detp: fractional distance to 3′ < 0.2 or > 0.8 (31)

ad: mutant allele depth in tumor ≥ 4

gad: mutant allele depth in normal ≤ 3

ma: Only two alleles at position have read support ≥ 2

Variants that passed all above filters were marked PASS in the filter column of their VCF record. Otherwise, the names of each filter that the variant failed were recorded instead. A single VCF file was produced for each tumor sample, i.e., primary or metastasis.

SSNV Calling Compared with Mutect

A cross-validation of our variant analysis pipeline was performed using the Broad’s Mutect (34) calls for a single series (one primary tumor and three metastases from patient RPA08-0209). Mutect was run in its default configuration using the patient's matched normal as a control. The filtered sets of variant calls made by Mutect for each tumor vs. matched normal were then postprocessed identically to the variant calls made by our caller, classifying each identified variant as FULLY SHARED (present in all samples), PRIVATE (present in only one sample), or otherwise found in more than one, but not all samples. We then compared the categorized sets of variant calls for the RPA08-0209 series made by Mutect and our pipeline.

Overall, 2,301 variants were found in both sets in identical categories. An additional 732 variants were exclusive to Mutect’s set and 229 variants were exclusive to our set. Out of the 732 variants exclusive to Mutect’s set, there were 617 FULLY SHARED variants (84%), 105 PRIVATE variants (14%), and an additional 10 variants present in other sample combinations (1%). Out of the 229 variants exclusive to our set, 208 were classified as FULLY SHARED (91%), 10 were classified as PRIVATE (4%), and 11 were found in other sample combinations (5%). We then investigated why some of the variants found in Mutect’s set were not present in ours. Of the 617 FULLY SHARED variants in Mutect’s set, 611 variants were called by our mutation caller but filtered out. The two filters, MMQS and AMM, were responsible for filtering out the majority of these calls. These filters discard variants located on sequencing reads with a high number of other mismatched bases, attempting to reduce the number of false positives induced by poor quality and/or reads that are aligned incorrectly. Of the 105 PRIVATE variants exclusive to Mutect’s set, 88 were not called by our mutation caller (84%), and 17 were filtered out (16%). As expected, these 88 variants had low alternate allele frequencies, the inclusion of which is a major strength of Mutect’s mutation model. Because PRIVATE variants with low allele frequencies most likely arose late during the development of these tumors postdivergence, they provide limited information the phylogenetic analyses focal to this report.

Indel calling was performed by Strelka using default parameters except with its depth filter turned off as recommended for exome sequencing input data (35). All somatic indels called by Strelka were collected for each sample. The PRESENT/ABSENT status for each indel was then determined for samples in a patient series in a manner identical to how substitution SSNVs were handled, as described above.

Classification of SSNV Detection States in Individual Patients

All variants discovered in any of the samples from a given patient were then combined to determine whether that variant was present in all samples. Variants that failed one or more filters in all samples of the series were removed. For variants that were marked PASS in at least one sample of a series, sample-specific metrics of the variant were collected for all samples in the series, including overall read depth, reference and alternate allele depths, failed filters (if any), as well as general information of the variant such as protein change, variant classification, and the number of samples in the COSMIC database that have a mutations at the same position (Release v55; ref. 36). The filter criterion of ≥8 unique reads listed above allowed for the possibility that variants present in low fraction in one of the samples in a series could be missed. To account for this possibility, the reference and alternate allele read depths for all samples including the matched normal of the series were updated using the raw sequencing data in each sample’s BAM file, tallying the number of reference and alternate alleles with base quality ≥20.

Based on the stringent PASS designation detailed above for individual variants, each somatic variant was then classified as PRESENT or ABSENT for each sample of a patient. A variant was classified as PRESENT if (i) it was called PASS in the sample or (ii) if it was detected at any depth in the sample’s raw sequencing data and called PASS in at least one other sample in the same patient. A variant was classified ABSENT if called PASS in at least one other sample in the same patient, but lacking any evidence in raw sequencing data for the sample in question. Somatic variants classified as PRESENT in all samples of a patient were further classified as FULLY SHARED, if all tumors in that patient shared these variants, indicating that they derived from a common ancestor cell, harboring that variant. All other variants were classified as NON-FULLY SHARED, indicating that they reside on a later-arising evolutionary branch.

Classes of SSNVs with identical PRESENT/ABSENT status across all samples in a patient were further analyzed regarding phylogenetic relationships between samples. To focus on classes supported by the greatest evidence, we required (i) at least three SSNVs per class and (ii) that each member SSNV had sufficient sequencing coverage to establish a TVP with a 99% confidence interval of <1 (given the mean normal cell contamination across all samples, this threshold was ≥42 reads after elimination of duplicates). We further observed that weakly supported variant calls (i.e., total read depth <42 reads in all tumors and matched normal) tended to be found in poorly captured or off-target regions of the genome, further justifying their exclusion.

The number of SSNVs that met these thresholds and were classified into classes (represented as tiers in Fig. 1 and detailed fully in Datasets S3 and S7) were as follows: patient A 2467/2749 SSNVs; patient B 98/141 SSNVs; patient C 1408/1573 SSNVs; patient D 1159/1332 SSNVs; patient E 96/148 SSNVs; patient F 3936/4968 SSNVs; patient G 760/856 SSNVs; and patient H 3053/3619 SSNVs.

Promoter mutations in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) (13) were manually inspected—the C228T mutation was detected in tumors of patients F and G, and the C250T mutation was found in tumors of patients A, C, and D. The mutations were fully shared among all tumors of all patients, with the exception of the distant back metastasis of patient F, however only 20 reads covered this position, making it likely it was present but insufficiently sampled.

Ion Torrent Validation Sequencing

From each sample, amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts, 10–100 ng were input into the Ion Xpress Plus Fragment Library Kit. Sequencing template was generated using emulsion PCR on the Ion OneTouch 2 using the Ion PGM Template OT2 200 kit. Up to 12 barcoded samples were multiplexed on Ion 318 v2, or Ion 316 v2 chips. Sequencing was performed on a Personal Genome Machine (PGM) sequencer (Ion Torrent) using the Ion PGM 200 v2 sequencing kit. Torrent Suite software version 4.0.2 was used to align reads to hg19. Reads were visualized using IGV v 2.2.32 (Broad Institute) and variant allele frequencies were determined for sites previously identified via Illumina sequencing.

Calling of Copy Number Aberrations

For copy number aberrations/variants, referred to here as CNAs, average tumor vs. matched normal relative coverage and SD were calculated for each captured exon by dividing read depth measured in the tumor by the read depth in the matched normal for each position within the exon. Exons that were insufficiently covered (average read depth <5 reads) in both tumor and matched-normal were removed from the remaining analysis. Average relative coverage was corrected for GC bias using LOWESS regression. The average majority allele fraction in both tumor and matched normal was computed for exons with at least one heterozygous SNP in the normal tissue:

where and are the read depths of the germ-line allele with the greatest read support and and are the total read depths at the position in the tumor and matched normal, respectively. Relative coverage is determined simply by dividing the coverage observed in tumor by the matched-normal’s coverage, i.e., . The SD of estimates was computed for exons featuring at least three heterozygous SNPs.

To determine copy number variants, the exon-level statistics computed above were iteratively aggregated into larger segments in an agglomerative process similar in spirit to hierarchical clustering. In the first round, every pair of neighboring exons was analyzed. Neighboring exons that did not have significantly different relative coverage and (only for exons with heterogeneous SNPs) estimates (P > 0.999, two-sample Student’s t test) were merged into a single segment. The average relative coverage and for the new segment were calculated as the base pair count adjusted averages and SDs of the two individual exons measurements. This procedure was continued with neighboring segments using the same method. When no more segments could be merged, then any segment or exon with fewer than 1,000 reads and/or 10 heterozygous SNPs, were removed as their weak statistics may be impeding their immediate neighbors from being merged together. After culling these segments and exons, another round of iterative merging was performed, combining any newly neighboring segments that were compatible, until no more compatible segments remained. The relative coverage estimates of all segments were centered to the median of the entire genome, which was assigned the value of 1.0, signifying the normal copy number state. A skew in estimates caused when the majority allele’s read support arose from sampling bias instead of an underlying imbalance in allele copy number was corrected by subtracting out the estimated in the matched normal sample. However, because such sampling bias only occurs in regions in which both alleles have roughly equal copy number, the correction was made using the following equation:

The corrected set of segments and exons were then manually reviewed to search for larger regions of contiguous segments that have similar relative coverage and estimates, indicating that all contiguous segments share the same allelic state. For region j, the region’s relative coverage and allele fraction is defined as the average of all segments’ estimates within the region, hereafter referred to as and . Because the samples in a patient series will exhibit copy number events that are shared by all samples or limited to just a subset of samples, the union of unique boundaries determined the final set of curated regions collected in Dataset S5.

Determining Allelic States from Relative Coverage and Allele Fraction

An integral allelic state, such as diploid (1, 1) or single copy gain (2, 1), will have an expected copy number CN (2 and 3 for the two preceding examples), and allele fraction AF (50/50 and 66.6/33.3 for the two preceding examples) for a given allelic state i based on the following equations:

where , are the copy numbers of the majority and minority alleles for the ith allelic state in the tumor, are the copy numbers of each allele in the matched-normal samples (assumed to be diploid, ), and is the fraction of normal contaminant the tumor sample.

To determine the allelic state most likely to produce the observed relative coverage and allele fraction estimates, we determine three parameters that transform the observed data to the expected values of copy number and allele fraction from the set of possible allelic states. The three parameters are as follows: fraction of normal contamination , relative coverage delta , and relative coverage scaling factor . The parameter controls the expected estimates for and , and the latter two parameters transform the observed estimates of relative coverage. The parameters and affect the y axis shift and scale of a segment’s relative coverage estimate from the diploid allelic state (1, 1) according to the following equation:

where is observed relative coverage and is the observed relative copy number of segment j.

The optimal values for these three parameters were discovered using a gradient steepest descent search to find the minimum root mean square deviation (RMSD) across all regions for a tumor sample in Dataset S5. The minimal deviation of region j was determined by comparing and to the expected values of the closest allelic state:

The allelic state i (, that produces the minimal deviation was recorded as the most likely allelic state for region j given the current parameter set. The of all regions was then computed as the square root of the sum of all regions’ minimal deviations weighted by their genomic widths, , to normalize the influence of shorter regions relative to larger regions on the computation: .

The search began with a set of initial values for each parameter (, , and , and a set of increments for each parameter, , , and [ ranged from 0 to 1 in increments of 0.2 (5 steps), ranged from 0.5 to 4 in increments of 0.5 (5 steps), and ranged from 0.1 to 0.9 in increments of 0.2 (4 steps)]. For each parameter, , and parameter increment, , the was calculated for , , and . The parameter value that yields the greatest reduction in was chosen as the new current value for that parameter. The current values of all parameters and their incremented counterparts were used to calculate a new set of s from which the next update to a parameter’s value was selected, and so on. If no reduction in was possible with the current parameter increments (i.e., the current values of the three parameters have the lowest ), then each increment was divided half and the search resumed. After three rounds of such parameter divisions, the search was concluded and the final values of the three parameters were recorded as the best fit parameters. Because gradient descent searches can fall into local minima, the gradient search process was performed multiple times with different initial parameters until a consistent set of fit parameters was converged upon. Then, in a manual process, the expected and observed estimates using the final set of parameters were compared with determine whether or not the gradient search found a good solution.

If a consistent set of fit parameters could not be determined after numerous parameter initializations, or if the best fit parameters failed to properly model the observed data upon manual review, the three parameters were manually adjusted until a reasonable fit was found. A total of 5 × 5 × 4 = 100 starting points were used.

We used an interactive web-based tool that graphs the relative coverage and allele fraction estimates for all segments on a scatter plot, correcting relative coverage using the best fit values for d and s. The position of several allelic states [e.g., (1, 1), (2, 1), (2,0), etc.] were overlaid on this graph after adjusting their positions by the best fit values for alpha. The positions of the allelic states were compared with the clusters of segments to see if large clusters overlap the position of an allelic state. The observed data were “properly” modeled by the fitted parameters when all or most large clusters center around an allelic state. If many large clusters were not found on an allelic state, the interactive tool was used to adjust the parameters , , and to see if a better fit could be determined manually.

The finalized set of parameters was used to determine the closest allelic state for each region j in the manner described above. Regions with observed copy number and allele fraction estimates that place them in between two allelic states indicated that they were “potentially” subclonal based on their relative coverage and allele fraction, which was then verified or nullified via the TVP estimates described in detail in Calculation of TVP and 99% Confidence Intervals for CNAs.

All of the states listed in Dataset S5 were tested up to a copy number of 5 [i.e., (1, 0), (1, 1), (2, 0), (2, 1), (2, 2), (3, 0), (3, 1), (3, 2), (3, 3), .... (5, 0), (5, 1), (5, 2), (5, 3), (5, 4), (5, 5)]. In addition, we also tested a range of extreme amplification with and without LOH: [(6, 1), (7, 1), (8, 1).... (30, 1), (6, 0), (7, 0), (8, 0).... (30, 0)]. The precise mixture of allelic states was determined with the method described below.

Determining Total Unique Copy Number Variants Found in Each Patient

For each curated segment, a unique set of all copy number states was identified for all tumor samples in the patient. If a region was subclonal in a sample, then the two integral copy number states that can be combined to produce the observed copy number state were added to the set. The unique set of copy number states was then deduced. Because FISH analysis (below) supported a predominantly (1, 1) diploid state in A–G, if a (1, 1) allelic state was detected, we deduced that that region harbored no copy number variants. If all samples shared an identical aberrant state [i.e., other than (1, 1)], that variant was determined to be FULLY SHARED. All other remaining copy number states—those demonstrating copy number aberrations in some but not all samples—were defined as NON-FULLY SHARED. The number of FULLY SHARED, NON-FULLY SHARED states, as well as total number of samples with subclonal allelic states, were tallied for each curated segment and are detailed in Dataset S5.

Calculation of TVP and 99% Confidence Intervals for SSNVs

We sought to calculate proportion of tumor cells in a sample that contained each SSNV (TVP). In contrast, the allele frequency of a mutation is the proportion of all DNA strands that contained each SSNV, with higher copy number and normal contamination affecting that proportion. It is therefore necessary to translate the proportion of DNA strands containing a SSNV into the proportion of tumor cells containing the strand. A principled statistical approach to determine this proportion required an estimate of the normal cell contamination of the sample, the copy number state at the SSNV, and the number of reads of its reference and mutant allele.

To calculate the TVP we assume that there are two populations of tumor cells, A and B, with the proportion of tumor cells coming from population A being the TVP. We assume each population is homogeneous so that for all cells in population A there are strands (or copies) of DNA covering the SSNV location and of these strands contain the SSNV. We similarly define and for the B population. Then with no normal contamination we can write the allele frequency of the SSNV as

With normal contamination, proportion of the cells are normal cells each of which contributes two strands of DNA and, by assumption, do not contain the SSNV. In this case the allele frequency of the SSNV becomes

We invert this equation to solve for the TVP,

However, when searching for subclonal SSNVs, by definition, we were interested only in those mutations that are found in one clone but not the other, so in these specific instances, either or . To simplify the analysis we only considered regions in which the two populations, A and B, have the same total copy number status, so that and we could assume that , i.e., only one copy in the A clone was mutated. This leads to the simplified equation:

For each SSNV, we calculated the allele frequency by dividing the number of variant reads by the number of total reads at the position. We calculated standard 99% binomial CI for the estimate of allele frequency using the binom.test function in R. We then used the formula for TVP above to convert these into estimates and 99% confidence intervals for the TVP.

Distinguishing Groups of SSNVs Defining Tumor Subclones

The large number of SSNVs in our study increases the risk of spurious false positives when identifying a tumor subclone based purely on a single SSNV. We therefore searched for groups of SSNVs demonstrating concordant changes in TVP between samples, which would provide much greater support for existence of a distinct tumor subclone (14). To identify such concordant changes, only for regions of normal copy number, TVPs of all SSNVs from one tumor were mapped against their TVPs in each other tumor from that patient. The resulting graphs were visually examined for evidence of clusters of SSNVs distinct from shared clonal SSNVs (TVP of 1,1). Such a pattern was only detected in patient C. SSNVs from each sample of patient C were split into groups according to a threshold on their TVP value. The threshold was determined by Otsu’s method (37), which uses a brute-force approach that tests every possible threshold that splits a set of values into two groups and then selects the threshold that minimizes the total intragroup variance. The thresholds selected for each sample, t_primary = 0.55, t_locoregional1 = 0.29, and t_locoregional2 = 0.35, were integrated to define a set of SSNV groups for the tumors of patient C, distinguished by color and shape in Fig. 4. A total of six groups were possible by choosing points above and below each threshold in a combinatorial manner, e.g., group 1 is the set of points >t_primary, >t_locoregional1, and >locoregional2; group 2 are the set of points <t_primary, >t_locoregional1, and <t_locoregional2, and so on until every combination of the three thresholds are made. Groups with fewer than two SSNVs were removed. The four remaining groups shown in Fig. 4 are described as follows:

Group 1/yellow (> t_primary, > t_locoregional1, > t_locoregional2) = 855 SSNVs

Group 2/blue (< t_ primary, > t_locoregional1, > t_ locoregional 2) = 142 SSNVs

Group 3/red (< t_ primary, > t_locoregional1, < t_ locoregional 2) = 20 SSNVs

Group 4/green (< t_ primary, < t_locoregional1, > t_ locoregional 2) = 15 SSNVs.

The TVPs for the SSNVs in group 1 extend leftward in Fig. 4, approaching 0.55. It is theoretically possible that some the group 1 SSNVs with the lowest TVPs may actually be at subclonal abundance. However, if this were the case, they would still segregate identically with the blue group 2 SSNVs, reaching fully clonal abundance in both locoregional metastasis 1 and 2, and thus would not alter our conclusions regarding the cell populations founding metastases.

Calculation of TVP and 99% Confidence Intervals for CNAs

We used the bias-corrected estimates of the allele frequency of the majority allele (described in the previous paragraph) to compute TVP for each CNA region, representing the proportion of cells in the tumor containing the CNA. Given the normal cell contamination estimate, , we calculated the percentage of tumor cells with the major allelic state A and minor allelic state B using the following equation:

are the majority allele copy number and the total copy number of the A and B allelic states, respectively, assuming the segment was diploid in the matched normal DNA. If the TVP value was greater than 1.0 or less than 0.0, it was truncated to be within this range. If the estimate of TVP was less than 0.5, the A and B allelic states were swapped so that the allelic state A remained the dominant clone.

The derivation of the equation for the TVP for a CNA region follows that described previously for an SSNV. The difference here is that the allele frequency is now the allele frequency of the majority allele strand, rather than the allele frequency of a mutation at a single nucleotide, and the number of copies of the majority allele () take the place of the number of copies that contain the mutation (). Furthermore, because for CNAs we are interested in comparing populations A and B that have different copy number alterations, we no longer make the simplifying assumptions regarding the values of and that were made in the analysis of SSNVs.

The estimate of TVP was determined by applying the above formula to the estimate of the of the majority allele, as determined by the allele frequencies in the SNPs contained in the region and corrected for bias as described in the next section. The confidence intervals for TVP were calculated by applying the formula to the upper and lower 99% bootstrap confidence intervals of the . If the confidence interval of the TVP was greater than 0.01 and less than 0.99, then the curated region was considered to be a mixture of two allelic states, and therefore deemed subclonal. Only CNAs for which such estimates and confidence intervals of the AF could be reliably calculated, as we describe more fully below, were considered for estimation of TVP.

Correcting Sources of Bias in SNP Allele Frequency in the Calculation of TVP for CNAs

To calculate the TVP of the CNAs, we first estimate the allele frequency of the major allele, defined as the number of strands of DNA in all cells that come from the major allele. To do so, we use the individual SNPs in the region, each of which provides an independent estimate of the major allele frequency, and combine them together to get a single estimate of allele frequency.

As described earlier, the average majority allele fraction is simply calculated for heterozygous SNP in the normal tissue as

where is the read depths of the germ-line allele with the greatest read support and is the total read depths at the position i in the tumor. If it were possible to comprehensively phase SNPs as in whole genome sequencing data, random variation in the allele frequency across SNPs would average to 0.5. However, as phasing is very limited in exome sequencing data, as in this study, we rely on the read depths to phase the SNPs as well as estimate the allele frequency. This generates a small, persistent bias based on misidentification of a “majority” allele as the result of stochastic sampling error (i.e., those values slightly above 50%), with the bias being larger when the true allele frequency is closer to 0.5, namely regions where both alleles have equal copy number. The bias also depends on the sequencing depth, with SNPs with larger depth giving less biased estimates.

In identifying CNA regions and estimating their copy number, we described above that we accounted for this bias in a way that did not require information about their copy number status and relied on using the observed AF for the SNP in the normal to correct for the bias. In calculating the AF for TVP calculation for CNA regions, we assume that the copy number status has been correctly identified, and in this setting we more formally calculated an SNP specific bias correction based on a probabilistic model.

We assume for a CNA that we have identified the dominant clone of the region, and that this dominant clone has allele specific copy number , for example (2, 1). implies an allele frequency for the major allele in the dominant clone, adjusted for normal contamination , which we designate as . Then the corrected estimate of allele frequency of an individual SNP is given as

is the expected bias for the allele frequency based on a binomial model and is specific to the sequencing depth of that SNP. is a further bias correction applied to all SNPs in the CNAs with the same dominant clone copy number . We describe in more detail below the determination of and .

We calculate for all SNPs in the CNA region, restricting ourselves to SNPs with sequencing depth , and to those SNPs where the normal tissue had . Furthermore was not able to be reliably estimated for some dominant clone values, as described more fully below. To estimate the allele frequency of the entire CNA region, we took the median of the n individual estimates (where n is the number of SNPs in the CNA region).

We calculated 99% confidence intervals of the allele frequency via a nonparametric bootstrap: resampling of the values and calculating the median, then repeating 5,000 times. The 99% confidence intervals are the 0.025 and 0.975 quantiles of the bootstrap resampling distribution, truncated to be between 0 and 1 (inclusive).

Derivation of

For each SNP if we know the true allele frequency , we can calculate the expected bias of under a binomial distribution, ; in what follows we drop the subscript i for simplicity. Because the sequencing depth, m, is generally large, we used a normal approximation for the expected bias:

where and and are the standard normal density and cumulative distribution functions, respectively. For , is generally negligible. This gives us an initial bias-corrected estimate of the allele frequency,

where is taken to be the allele frequency implied by the allele-specific copy number for the dominant clone in the CNA, adjusted for normal contamination [so that for SNPs in (1, 1) and (2, 2) regions]. Again, only for regions with for the dominant clone will this bias correction be nonnegligible. In such CNA regions, if the region is truly subclonal this estimate will generally be an overestimate of the bias, making our detection of the subclonal region more conservative (because will be pulled closer to 0.5).

Derivation of

A close inspection of our results using this approach indicated that some, but not all, bias was accounted for by this stochastic model [and therefore corrected by subtracting off ]. When we compared our expected bias to the observed values of across the thousands of SNPs that come from regions with , we observed that slightly underestimated the bias in our observed data. Moreover, this difference was different for different samples, and was also different from what we saw if we compared the normal SNPs () to their expected bias. We observed a similar difference between the expected allele frequency and the observed allele frequency in regions with an expected majority allele frequency not equal to 0.5 (and therefore not affected by the bias in calculating the allele frequency). For some samples, there were a sufficient number of regions of a similar allelic copy number to observe that this was a shared bias, not due to subclonality. Because our estimate of subclonality rests on finding differences between the observed and expected allele frequency, this difference could result in falsely detecting subclonality.

There are several understood reasons why such systematic bias may persist. For example, by mapping to a reference genome, SNPs missing from databases or SSNVs will reduce successful mapping and favor an arbitrary allele. To reduce the impact of such other forms of systematic bias, we further corrected the observed allele frequency of each SNP by calculating the median value of this difference across all SNPs with the same allelic copy number [e.g., (1,0)], denoted as . We subtracted from before calculating our final bias-corrected estimate of allele frequency. We only did this for tumor samples with sufficient numbers of regions to be able to do this robustly so that no region unduly influenced our adjustment of the expected value of the allele frequency. Specifically, for calculating we only considered regions that had at least 50 SNPs with sequencing depth greater than 100 and further required the sample to have at least 5 such regions with the same allelic copy number. If a sample had fewer than five regions of a specific allelic copy number or if any single region contained greater than 30% of the total SNPs for a given allelic copy number, then regions with that allelic copy number did not have an estimate of and therefore were not given allele frequency estimates for the purposes of subclonality estimation. The total number of segmented regions per series ranged from 29 to 76 across the seven series. Those that satisfied the criteria and received an allele frequency and thus a TVP estimate ranged from 23 to 49 (60–96% of segments).

FISH

To validate the copy number calls determined in the section Determining Allelic States from Relative Coverage and Allele Fraction, we performed four-color FISH analysis on 5-µm tissue sections as previously described using probes targeting 6p25 (RREB1), centromere 6, 6q23 (MYB), and 11q13 (CCND1)13 for patients A and C. Signals for each probe were enumerated for at least 30 nuclei of each tumor tissue and the averages calculated. The averages for each probe were compared to the copy number state of the corresponding genomic regions, and based on that comparison the dominant copy number state for the entire tumor sample was judged as diploid for these cases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Pinkel for a critical reading of the manuscript and John Constantine and Celeste Bailey for assistance with illustration. This work was supported by the Well Aging Research Center, Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology, under the auspices of Professor Sang Chul Park, the Dermatology Foundation, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Grants K08 CA169865 (to R.J.C.), the Integrative Cancer Biology Program, U54 CA112970, and by the Oregon Health & Science University Knight Cancer Institute (J.W.G. and P.T.S.). R.A.S. is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship program. This work was also supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council program grant. Assistance from colleagues at Melanoma Institute Australia and the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital is also gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The raw sequence reads from this study have been deposited with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession no. phs000941.v1.p1.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1508074112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Faries MB, Steen S, Ye X, Sim M, Morton DL. Late recurrence in melanoma: Clinical implications of lost dormancy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(1):27–34, discussion 34–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reintgen D, et al. The orderly progression of melanoma nodal metastases. Ann Surg. 1994;220(6):759–767. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199412000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch CM, et al. Efficacy of an elective regional lymph node dissection of 1 to 4 mm thick melanomas for patients 60 years of age and younger. Ann Surg. 1996;224(3):255–263, discussion 263–266. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199609000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton DL, et al. MSLT Group Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1307–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulmer A, et al. Immunomagnetic enrichment, genomic characterization, and prognostic impact of circulating melanoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(2):531–537. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0424-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid AL, et al. Markers of circulating tumour cells in the peripheral blood of patients with melanoma correlate with disease recurrence and progression. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(1):85–92. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodis E, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150(2):251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turajlic S, et al. Whole genome sequencing of matched primary and metastatic acral melanomas. Genome Res. 2012;22(2):196–207. doi: 10.1101/gr.125591.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabbarah O, et al. Integrative genome comparison of primary and metastatic melanomas. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell PJ, et al. The patterns and dynamics of genomic instability in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature09460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies H, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinfeld B, et al. Stabilization of beta-catenin by genetic defects in melanoma cell lines. Science. 1997;275(5307):1790–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang FW, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339(6122):957–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1229259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nik-Zainal S, et al. Breast Cancer Working Group of the International Cancer Genome Consortium The life history of 21 breast cancers. Cell. 2012;149(5):994–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damsky WE, et al. β-catenin signaling controls metastasis in Braf-activated Pten-deficient melanomas. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(6):741–754. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallagher SJ, et al. Beta-catenin inhibits melanocyte migration but induces melanoma metastasis. Oncogene. 2013;32(17):2230–2238. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi H, et al. Acquired resistance and clonal evolution in melanoma during BRAF inhibitor therapy. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(1):80–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Allen EM, et al. Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group of Germany (DeCOG) The genetic landscape of clinical resistance to RAF inhibition in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(1):94–109. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan RN, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438(7069):820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAllister SS, et al. Systemic endocrine instigation of indolent tumor growth requires osteopontin. Cell. 2008;133(6):994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comen E, Norton L, Massagué J. Clinical implications of cancer self-seeding. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(6):369–377. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norton L, Massagué J. Is cancer a disease of self-seeding? Nat Med. 2006;12(8):875–878. doi: 10.1038/nm0806-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo X, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of circulating melanoma cells. Cell Reports. 2014;7(3):645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aceto N, et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell. 2014;158(5):1110–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagle N, et al. Dissecting therapeutic resistance to RAF inhibition in melanoma by tumor genomic profiling. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(22):3085–3096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yachida S, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1114–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navin N, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472(7341):90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katalinic A, et al. Does skin cancer screening save lives?: An observational study comparing trends in melanoma mortality in regions with and without screening. Cancer. 2012;118(21):5395–5402. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H, Ruan J, Durbin R. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008;18(11):1851–1858. doi: 10.1101/gr.078212.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, et al. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larson DE, et al. SomaticSniper: Identification of somatic point mutations in whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(3):311–317. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welch JS, et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012;150(2):264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellis MJ, et al. Whole-genome analysis informs breast cancer response to aromatase inhibition. Nature. 2012;486(7403):353–360. doi: 10.1038/nature11143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cibulskis K, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saunders CT, et al. Strelka: Accurate somatic small-variant calling from sequenced tumor–normal sample pairs. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(14):1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forbes SA, et al. COSMIC: Mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D945–D950. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1979;9(1):62–66. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.