Significance

Many of the world’s major chronic diseases are driven by inflammation. The most abundant inflammatory cells in these diseases are myeloid cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils. Both cell types show remarkable phenotypic diversity among tissues. Defining molecular factors that control this diversity provides abundant scope for the generation of more specific and effective therapeutics, as the lack of specificity of the current most widely used antiinflammatory approaches, such as glucocorticoids and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory molecules, leads to widespread problems if used long term, even at relatively low doses. In this study we demonstrate that a transcription factor called IFN regulatory factor 5 controls macrophage and neutrophil aspects of inflammation, and thus its blockade might be an effective therapeutic strategy for multiple indications.

Keywords: macrophages, neutrophils, IRF5, acute inflammation, arthritis

Abstract

Whereas the importance of macrophages in chronic inflammatory diseases is well recognized, there is an increasing awareness that neutrophils may also play an important role. In addition to the well-documented heterogeneity of macrophage phenotypes and functions, neutrophils also show remarkable phenotypic diversity among tissues. Understanding the molecular pathways that control this heterogeneity should provide abundant scope for the generation of more specific and effective therapeutics. We have shown that the transcription factor IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) polarizes macrophages toward an inflammatory phenotype. IRF5 is also expressed in other myeloid cells, including neutrophils, where it was linked to neutrophil function. In this study we explored the role of IRF5 in models of acute inflammation, including antigen-induced inflammatory arthritis and lung injury, both involving an extensive influx of neutrophils. Mice lacking IRF5 accumulate far fewer neutrophils at the site of inflammation due to the reduced levels of chemokines important for neutrophil recruitment, such as the chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1. Furthermore we found that neutrophils express little IRF5 in the joints and that their migratory properties are not affected by the IRF5 deficiency. These studies extend prior ones suggesting that inhibiting IRF5 might be useful for chronic macrophage-induced inflammation and suggest that IRF5 blockade would ameliorate more acute forms of inflammation, including lung injury.

Myeloid cells are critical components of host defense. Macrophages (MPHs) and neutrophils are the two major types of myeloid cells involved in inflammatory disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which is a chronic degenerative disease characterized by joint inflammation and bone destruction affecting up to 1% of the population (1). The molecular pathogenesis of RA has been extensively studied, and some aspects have been understood. Excess TNF is pathogenic, as witnessed by the extensive use of TNF inhibitors, which in 2014 were the world’s best-selling medicines. Most of the TNF in RA is produced by synovial macrophages. The increase in the number of sublining macrophages is an early hallmark of active rheumatic disease (2), with augmented numbers of macrophages being a prominent feature of inflammatory lesions (3). The degree of synovial macrophage infiltration correlates with the degree of joint erosion (4), and their depletion from inflamed tissue has a profound therapeutic benefit (5). Neutrophils also play an important but less understood role in RA pathogenesis (6). The potential importance of neutrophils is suggested not only by their abundance, e.g., in synovial fluid of RA patients and within the pannus in patients with active RA (7, 8), but also by the neutrophil formation of extracellular traps (NETs), which can provide a source of destructive enzymes as well as autoantigens (9).

In recent years there has been a growing understanding of the heterogeneity of macrophages (10, 11) and, more recently, awareness that neutrophils may also form distinct subsets (12, 13). The exact nature of the myeloid cells in various inflammatory diseases is thus a topic of major interest, as it will not only provide clues about pathogenesis, but also contribute toward more effective therapeutics. In a mouse model of sterile inflammatory arthritis (K/BxN serum transfer induced arthritis) modeling only the effector part of the disease, nonclassical (Ly6C−) monocytes enter the joint and differentiate into classical inflammatory macrophages that drive joint pathology (14). During resolution, macrophages are “alternatively activated” and promote resolution and repair. The situation in models of RA, which involve induction as well as effector phases, or more importantly, in human RA, is not yet clear.

We have documented the importance of the transcription factor IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) in defining the classical inflammatory phenotype of macrophages (15, 16). IRF5 has also recently been reported to be expressed in neutrophils, specifically in neutrophils from synovial fluid of arthritic mice (13). Therefore, here we test the role of IRF5-expressing cells in antigen-induced arthritis (AIA), and document the importance of IRF5 in neutrophil joint accumulation. We find that neutrophils express little IRF5 while in the joints and that their migratory properties are not affected by the IRF5 deficiency. However, we observed a significant reduction in secretion of a major neutrophil chemoattractant, the chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 2 (CXCR2) binding chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL) 1. Neutrophil-dependent acute lung injury is also markedly reduced in the IRF5-deficient mice, indicating the importance of IRF5 in neutrophil recruitment beyond the joints. These results also document that IRF5 blockade would have a major impact on inflammation by altering both macrophage phenotypes and neutrophil recruitment, and hence defining IRF5 as a very interesting potential therapeutic target.

Results

IRF5 Ablation Limits Neutrophil Influx in the Inflamed Joint.

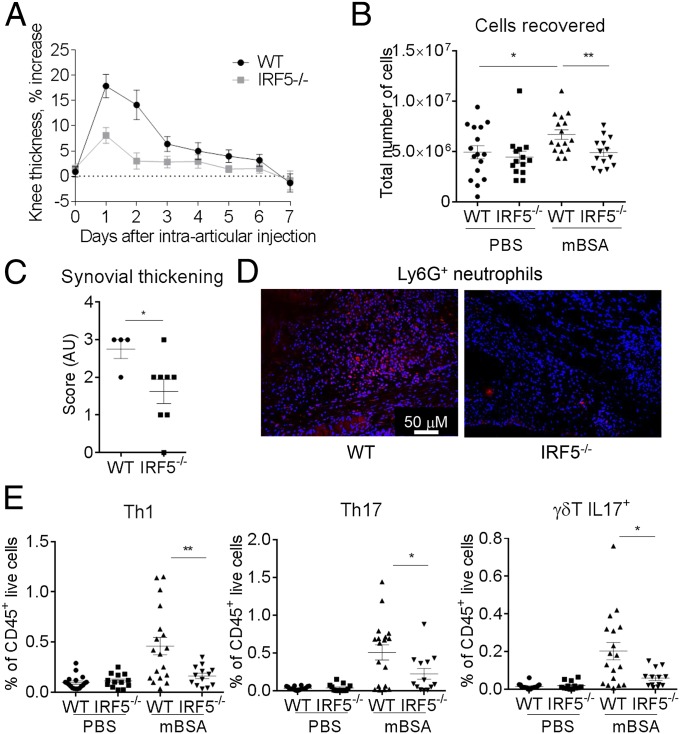

The murine model of antigen-induced arthritis relies on s.c. immunization with methylated BSA (mBSA) plus complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), followed by intraarticular injection of mBSA into the knee joint (17). The model is characterized by infiltration of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells, pannus formation, and erosion of bone and cartilage (17), and is Th17 dependent (18). We have previously reported that synovial macrophages from the AIA-affected joints are characterized by high levels of IRF5 (16). Here, we aimed to determine the role that IRF5 plays in synovial physiology and function in both naïve joints and during inflammatory arthritis. IRF5 deficient mice (IRF5−/−) and their littermate wild-type controls (WT) were immunized with mBSA in CFA and 7 d later, knees were either challenged with mBSA or PBS control (Fig. S1A). Knee swelling of WT mice was induced rapidly and peaked at day 2, after which time swelling decreased. IRF5−/− mice showed significantly less swelling at day 2 in comparison with WT controls (Fig. 1A). Reduced swelling corresponded to a decreased number of cells recovered from excised knee joints at that point (Fig. 1B). Knee pathology at day 2 was further assessed histologically for the degree of inflammatory infiltrate into the synovium and joint cavity, synovial capsule and synovial membrane thickness and bone erosion, respectively (Fig. S1B). IRF5 knockout mice displayed a significantly lower synovial membrane thickening score in the mBSA-challenged knees than WT mice (Fig. 1C). Consistent with resolved knee swelling at the later stages, we observed reduced synovial membrane thickening at day 7 (Fig. S1B).

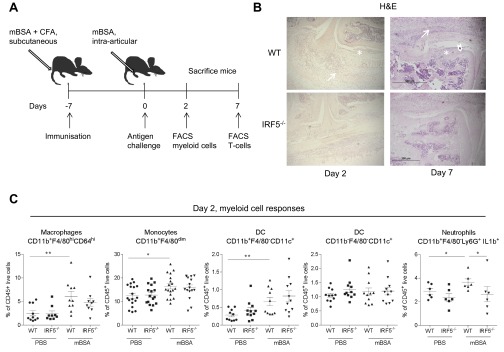

Fig. S1.

AIA model in IRF5−/− mice, innate immune responses. (A) Schematic diagram showing treatment and harvest time points in the antigen-induced arthritis model. (B) Representative images of the knee showing areas of bone erosion (arrowhead), synovial thickening (asterisk), and leukocyte infiltration into joint space (arrows). (C) Total number of macrophages, monocytes, DCs, and pro-IL-1β+ neutrophils recovered from excised knee joints of IRF5−/− and WT animals at day 2 of AIA, expressed as a percentage of live CD45+ cells. Data shown are the mean and SEM derived from 10–20 mice from three to four independent AIA experiments. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Statistical analysis was performed by one-tailed Mann–Whitney u test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. 1.

IRF5 ablation limits neutrophil influx in the inflamed knee. (A) Comparison of knee swelling between inflamed knees of the IRF5−/− and WT animals, expressed as a percentage of swelling of the mBSA-challenged knee compared with the PBS knee. (B) Total number of cells recovered from excised knee joints of the IRF5−/− and WT animals at day 2 of the AIA. (C) Synovial thickness of inflamed knees at day 2 post intraarticular injection of mBSA based on examination of histology slides (Fig. S1B). (D) Ly6G+ cells detected within the synovial capsule of inflamed knees in the IRF5−/− and WT animals, analyzed by immunohistochemical staining and confocal microscopy. Cell nuclei are marked by DAPI staining in blue and Ly6G+ cells are shown in red. Compare 52 ± 17 and 14 ± 3 Ly6G+ cells per field for WT and IRF5−/− (P = 0.0045). (E) Number of Th1, Th17, and γδ T IL17+ cells in the joints of mice at day 7 of AIA, expressed as a percentage of live CD45+ cells. Data show the mean and SEM derived from 10 to 20 mice from three to four independent AIA experiments. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Statistical analysis was performed by one-tailed Mann–Whitney u test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The observed difference in the number of leukocytes recovered from mBSA-challenged knees at day 2 compared with the PBS controls (Fig. 1B) was mirrored by the increase in myeloid cell numbers, i.e., CD11b+F4/80hiCD64hi macrophages, CD11b+F4/80dim monocytes, CD11b+F4/80+CD11c+ dendritic cells (DCs), and neutrophils (Fig. S1C). There was no change in the number of CD11b−F4/80−CD11c+ dendritic cells (Fig. S1C). Due to the likelihood of substantial influx into the neutrophil pool from the bone marrow (BM) when harvesting knees, we used pro-IL1β as a marker for activated neutrophils (19) and focused on synovial-activated neutrophils CD11b+F4/80−Ly6G+pro-IL1β+. The number of synovial-activated neutrophils was significantly reduced in inflamed knees of IRF5−/− mice (Fig. S1C), whereas the numbers of synovial monocytes, macrophages, and DCs were unaffected (Fig. S1C). This was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining of slides for Ly6G+ cells and cell counting, which demonstrated a clear reduction in synovial neutrophil infiltrate in the IRF5−/− animals (Fig. 1D). Neutrophils are thus the only myeloid cells, whose influx or propagation depends on IRF5 during early stages of AIA.

IL-17 produced by CD4+ (Th17) cells or γδ T cells plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AIA (18). Thus, we analyzed the number of IL-17 producing Th17 and γδ T cells in the joints of mice at days 2 and 7 of the disease. Minimal CD4+ and no γδ T-cell populations were detected at day 2, whereas by day 7, the T-cell response in WT mBSA knees was increased compared with day 2 (Fig. S2A). However, in IRF5−/− animals the T-cell response at day 7 was significantly reduced, affecting both Th17 and γδ T IL17+ cells, as well as IFNγ-producing Th1 cells (Fig. 1E). We also observed a reduction in the levels of IFNγ and IL-17A mRNA and of cytokines facilitating generation of Th1/Th17 cells, e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p40, and IL-23p19 (Fig. S2B).

Fig. S2.

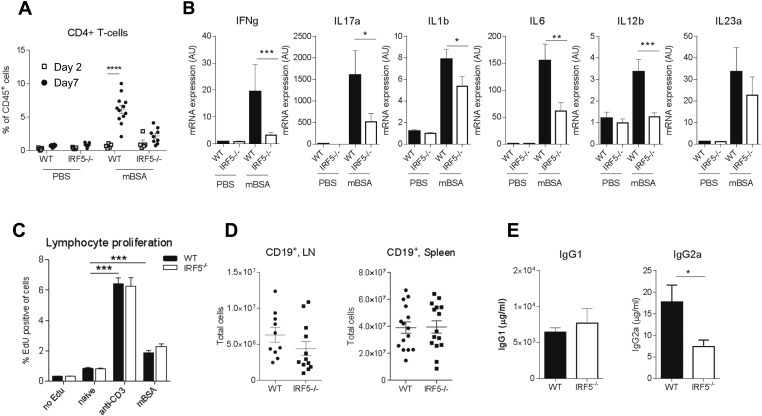

AIA model in IRF5−/− mice, adaptive immune responses. (A) IRF5 WT and KO were immunized with mBSA and challenged with mBSA or PBS control 7 d later. Knees were excised on day 2 or 7 of disease and analyzed using flow cytometry. Cell suspensions obtained from knees were stained for CD45+ live and CD4 expression to identify CD4+ T cells. Statistical analysis performed by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni‘s multiple comparison. (B) IL17, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p40, and IL-23p19 mRNA in whole joint extracts from arthritic mice at day 2 of AIA. Data shown are the mean and SEM derived from 10–20 mice from three to four independent AIA experiments. (C) Proliferation of lymphocytes after 48-h stimulation with αCD3 or mBSA. The data are mean and SEM derived from six independent lymphocyte cultures from lymph nodes (LNs) of IRF5−/− and WT arthritic mice. Statistical analysis was performed by one-tailed paired t test. (D) Total number of B cells in the lymph nodes and spleen. The data are mean and SEM derived from 10 to 15 independent cell preparations from LNs and spleens of the IRF5−/− and WT immunized mice. Each dot represents an individual mouse. (E) Levels of total IgG1 and IgG2a in the serum. The data are mean and SEM using 3–5 mice treated from a representative AIA experiment. Statistical analysis was performed by two-tailed unpaired t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001.

To assess a potential effect of IRF5 deficiency on the immunization process preceding the intraarticular challenge, inguinal lymph nodes were harvested 7 d after immunization. Lymph node cell suspensions were stimulated with α-CD3 or mBSA for 48 h and T-cell proliferation was measured. Both stimulations resulted in a significant increase in lymphocyte proliferation, including proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, but proliferative responses were unaffected by IRF5 deficiency (Fig. S2C). As B cells appear to play a critical role in arthritis pathogenesis (20), and express variable levels of IRF5, we examined B-cell numbers and function during the immunization of the IRF5−/− animals. No CD19+ B cells were detected in the joint, whereas the number of CD19+ B cells in the blood, spleen, and lymph node remained unaffected (Fig. S2D). Total B-cell (IgG1 and IgG2a) responses in the serum were assessed at day 2 of AIA and revealed no significant change for IgG1 and a reduction in the levels of IgG2a (Fig. S2E). This is in agreement with the previously documented role for IRF5 in the control of the IgG2a locus (21).

Taken together, the deficiency limits the neutrophil influx into the inflamed joint in the early stages of arthritis and leads to a reduction in the Th1/Th17 and γδT IL-17+ cells in the joint at the later stages.

Synovial Macrophages in the Naïve and Inflamed Knee.

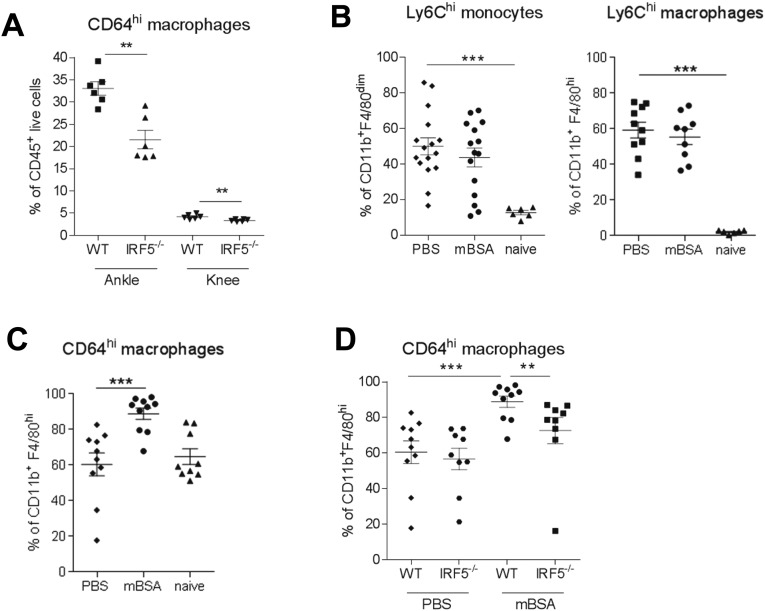

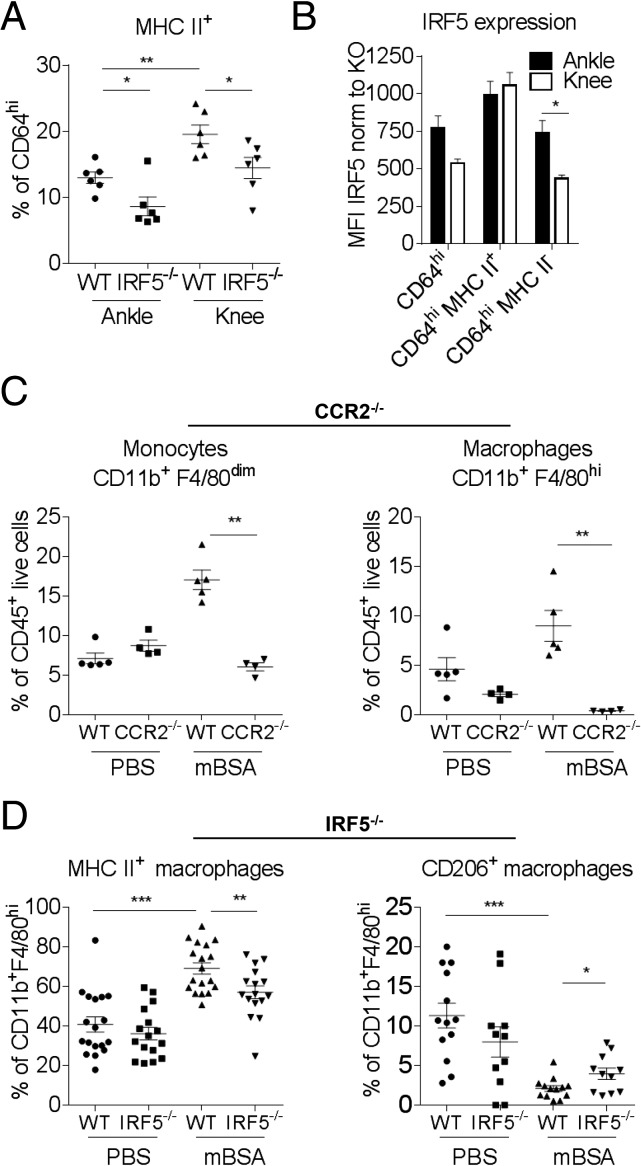

The phenotype and origin of macrophages in the knee joint in the steady state or during inflammatory arthritis are not known. Recent work by Misharin et al. demonstrated that the ankle synovial lining of naïve mice consists of a heterogeneous population of macrophages, with the majority being true tissue-resident cells (CD11b+CD11cintF4/80+CD64+MHCII−) and about a fifth originating from bone marrow (CD11b+CD11cintF4/80+CD64+MHCII+) (14). Applying a similar gating strategy (SI Appendix, FACS Gating Strategy and Representative Plots) we demonstrate that the total number of CD11b+F4/80+CD64+ macrophages in both ankle and knee is reduced in IRF5−/− mice (Fig. S3A). The reduction seemed to be mainly due to the effect on the number of MHCII+ macrophages (Fig. 2A) that display the highest level of IRF5 expression within macrophage populations (Fig. 2B). Of interest, we find a higher representation of MHCII+ macrophages in the knee than in the ankle (Fig. 2A), whereas MHCII− macrophages in the ankle express higher levels of IRF5 than their counterparts in the knee (Fig. 2B). These data highlight differences between the two joints in naïve animals.

Fig. S3.

Characterization of synovial macrophages. (A) Number of tissue resident CD64hi macrophages in both the ankles and knees of naïve IRF5−/− mice and WT controls. Data shown are mean and SEM derived from 4 to 7 mice from a representative experiment. (B) Number of Ly6Chi monocytes and macrophages, expressed as a percentage of CD11b+F4/80dim and CD11b+F4/80hi cells, respectively. (C) Number of CD64hi macrophages, expressed as a percentage of CD11b+F4/80dim and CD11b+F4/80hi cells, respectively. (D) Number of CD64hi macrophages in the mBSA-challenged knees or PBS controls of IRF5−/− and WT animals, expressed as a percentage of CD11b+F4/80hi cells. Data shown are mean and SEM derived from 10 to 11 mice from two to three independent AIA experiments. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Statistical analysis was performed by one-tailed Mann–Whitney u test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of synovial macrophages in naïve knees and during AIA. (A) Number of tissue resident MHCII+ macrophages in both ankle and knee joints of naïve IRF5−/− mice and WT controls. (B) IRF5 expression within tissue resident macrophage populations defined by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and normalized to MFI of IRF5-deficient animals. Data shown are the mean and SEM derived from 6 mice from a representative experiment. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05. (C) Number of CD11b+F4/80dim monocytes and CD11b+F4/80hi macrophages in the mBSA-challenged knees or PBS controls of CCR2−/− and WT mice, expressed as a percentage of live CD45+ cells. (D) Number of MHCII+ or CD206+ macrophages in the mBSA-challenged knees or PBS controls of IRF5−/− and WT animals, expressed as a percentage of CD11b+F4/80hi cells. Data shown are mean and SEM derived from 4–7 mice from a representative AIA experiment (A and C) or 10–20 mice from three to four independent AIA experiments (C and D). Each dot represents an individual mouse. Statistical analysis was performed by one-tailed Mann–Whitney u test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To elucidate the source of macrophages infiltrating the knee in response to mBSA challenge, AIA was performed using C-C chemokine receptor 2 deficient mice (CCR2−/−), which lack CCR2 expression on classical Ly6C+ monocytes essential for their trafficking (22). The influx of CD11b+F4/80dim monocytes and CD11b+F4/80hi macrophages was almost completely abolished in the mBSA-challenged joints of CCR2−/− mice (Fig. 2C). Ly6C was expressed on 80–90% of monocytes and macrophages in the knee joints of immunized mice, with 50–60% of those being Ly6Chi (Fig. S3B). This finding represents a drastic increase in the amount of Ly6Chi cells compared with steady-state joints without intraarticular antigen challenge. A total of 60% of macrophages in PBS-treated knees and 90% of macrophages in the mBSA-challenged knees were CD64hi (Fig. S3C). IRF5 deficiency did not affect monocyte, macrophage, or DC infiltrate into the mBSA-challenged knee (Fig. S1B), but expression of CD64 (Fc gamma receptor 1) on macrophages was reduced (Fig. S3D). Consistent with our previously reported observations (15), we observed a shift toward an alternatively activated macrophage phenotype in the IRF5−/− animals, with a lower number of macrophages expressing MHC II and higher numbers expressing CD206 (Fig. 2E).

Taken together, these data suggest that in the antigen-driven arthritis model, Ly6C+ circulating monocytes are preferentially recruited into the inflamed joint and give rise to Ly6C+ inflammatory macrophages. The presence of IRF5 appears to be important for differentiation of monocytes into CD64+ macrophages and for the establishment of the MHCII+ inflammatory macrophage phenotype in the arthritic joint.

IRF5 Controls Neutrophil Influx via Regulation of Chemokine Production Such as CXCL1.

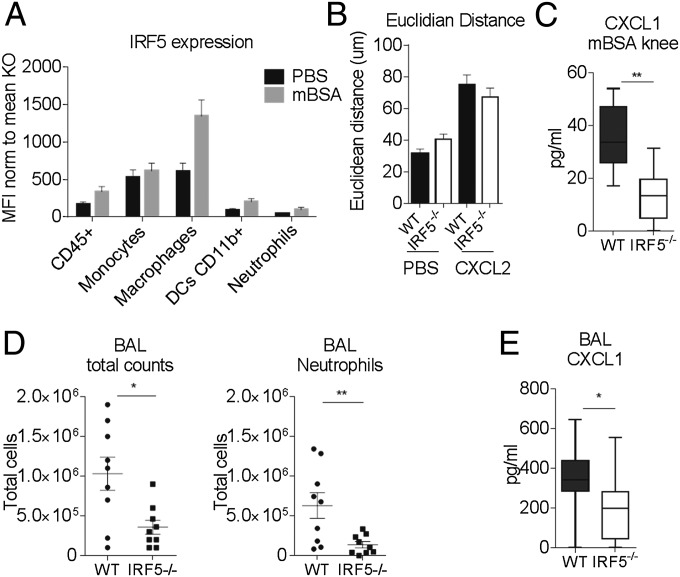

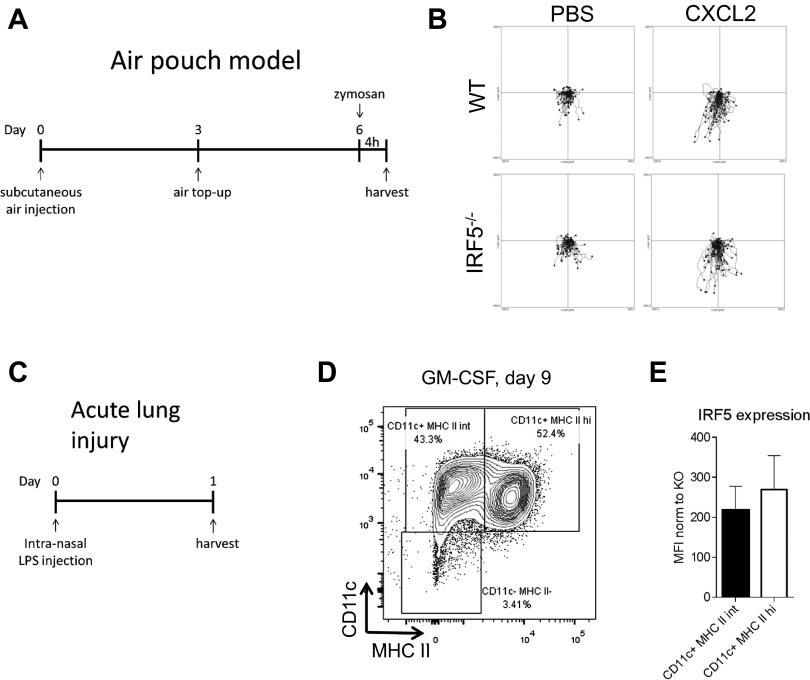

Because the recruitment of neutrophils into the knees of IRF5−/− animals was significantly reduced, we set out to examine whether neutrophils themselves were affected by the loss of IRF5. Firstly, we measured the levels of IRF5 expression in neutrophils in WT mice and found them to be significantly lower compared with monocytes and macrophages in the knee (Fig. 3A). Secondly, we examined the migratory capacity of neutrophils toward the neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL2 using the EZ-Taxiscan system, which allows visualization of cell migration in shallow, linear gradients and provides real-time analysis of neutrophil movement (23). Neutrophils were isolated from the air pouch, created on the dorsal surface of the mice and injected with zymosan (24) (Fig. S4A). Approximately 80% of the recovered cells after injection of 100 μg of zymosan were CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils. The Euclidean distance that neutrophils covered when migrating toward the attractant was comparable in WT and IRF5−/− cells (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4B). Notably, basal neutrophil movement, in the absence of any chemoattractant, was not affected either. Hence, we conclude that lack of IRF5 does not affect the intrinsic capacities of neutrophils to migrate toward a chemokine. To assess whether secretion of neutrophil attracting chemokines was altered in IRF5−/− mice, we analyzed levels of known neutrophil chemoattractants, such as CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL10, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL) 3, CCL4, CCL5, in the supernatants of synovial leukocytes isolated from mBSA-treated knees, by Luminex analysis. We found that the levels of CXCL1 were significantly affected by the loss of IRF5 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Neutrophil recruitment in IRF5−/− mice is limited due to the decrease in CXCL1 secretion. (A) IRF5 expression within cell populations of the inflamed knee defined by MFI. Data shown are the mean and SEM derived from 10–20 mice from three to four independent AIA experiments. (B) The tracks of air pouch neutrophilic infiltrate in an EZ-Taxiscan migrating toward CXCL2 (Fig. S4B) were analyzed to show the Euclidean distance each cell traveled in a 45-min time period. Data shown are the average and SEM of three independent experiments each including 9–20 movies per treatment. (C) Levels of CXCL1 in the supernatants of the synovial leukocytes isolated from the mBSA-treated knees. Data are shown as mean with 95% confidence interval from 6 mice from a representative AIA experiment. (D) Number of infiltrating cells and neutrophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) of the IRF5−/− and WT mice challenged with LPS intranasally. Each dot represents an individual mouse. (E) Levels of CXCL1 in BAL of LPS-challenged animals. Data are shown as mean with 95% confidence interval from 9–10 mice from two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by one-tailed Mann–Whitney u test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. S4.

Models of air pouch and acute lung injury and GM-CSF bone marrow cultures. (A) Schematic time line of the air pouch model showing s.c. air injections and challenge with zymosan. (B) Center-zeroed tracks of air pouch neutrophilic infiltrate in an EZ-Taxiscan migrating toward CXCL2. (Scale in μm.) (C) Schematic diagram showing treatment and harvest time points in the acute lung inflammation model. (D) Bone marrow progenitors were differentiated with GM-CSF for 9 d before samples were taken for flow cytometry. Cells were stained for the surface markers CD11b, CD11c, and MHCII. The depicted population was first gated by size and for CD11b expression. The plot is representative of n = 3. (E) Intracellular IRF5 staining in GM-CSF bone marrow cultures was quantified using MFI normalized to IRF5 KO. Error bars represent the SE for n = 3.

Next, we examined whether the reduction in neutrophil influx in IRF5−/− mice was confined to inflammation in the joint. We considered a model of acute lung injury, which is characterized by a high influx of neutrophils into the challenged lung (25). IRF5−/− and WT mice were administered LPS intranasally at 1 mg/kg body weight and culled 24 h later (Fig. S4C). IRF5−/− mice showed significantly less cellular infiltrate in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) and more specifically displayed a significant reduction in the number of neutrophils recruited into the lung 24 h post challenge (Fig. 3D). The number of other infiltrating myeloid cells such as monocytes and macrophages were not affected in the lung, but the levels of secreted CXCL1 were also significantly reduced once again (Fig. 3E).

In summary, the recruitment of neutrophils to the sites of inflammation is severely affected in the absence of IRF5, due to the deficient production of neutrophil chemoattractants.

IRF5 Orchestrates Expression of Chemokines in Bone-Marrow–Derived Macrophages.

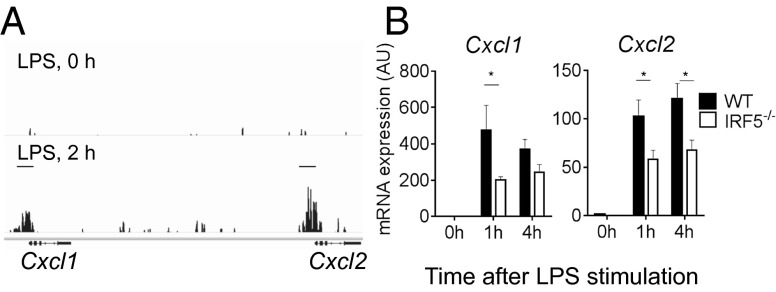

To investigate whether IRF5 is recruited to the chemokine gene control regions and whether the expression of chemokine genes in general is affected by the lack of IRF5, we used GM-CSF mouse bone marrow cultures, which represented a mix of macrophages and dendritic cells (GM-BM-DC/MPHs) (Fig. S4D) (26), both expressing similar levels of IRF5 (Fig. S4E). IRF5 ChIP-Seq datasets were generated in WT and IRF5−/− GM-BM-DC/MPHs and were stimulated with LPS for up to 4 h, as previously described (27). After filtering out false positive IRF5 binding peaks detected in IRF5−/− GM-BM-DC/MPHs, 2,538 bona fide binding peaks were mapped to gene promoter regions (up to 10 kb upstream and 0.5 kb of the transcription start site). The defined genes with IRF5 binding sites in their promoters were then subjected to gene ontology analysis, which produced the following categories of molecular functions: cytokine activity, cytokine receptor binding, chemokine activity, chemokine receptor binding (Hyper false discovery rate q-value <10–1010). Chemokines whose promoters were targeted by IRF5 in GM-BM-DC/MPHs stimulated by LPS for 2 h included CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL10, CXCL16, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL6, CCL9, CCL11, CCL12, CCL17, and CCL22 (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5A).

Fig. 4.

IRF5 controls chemokine network. (A) Representative UCSC (University of California, Santa Cruz) genome browser tracks in the Cxcl1/Cxcl2 loci for IRF5 binding peaks in unstimulated (LPS, 0 h) or LPS-stimulated (LPS, 2 h) GM-BM-DC/MPHs. (B) mRNA expression of selected chemokines in IRF5−/− and WT GM-BM-DC/MPHs stimulated with LPS for 0, 1, and 4 h using quantitative RT-PCR. Data shown are the mean and SEM derived from three mice from a representative experiment. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

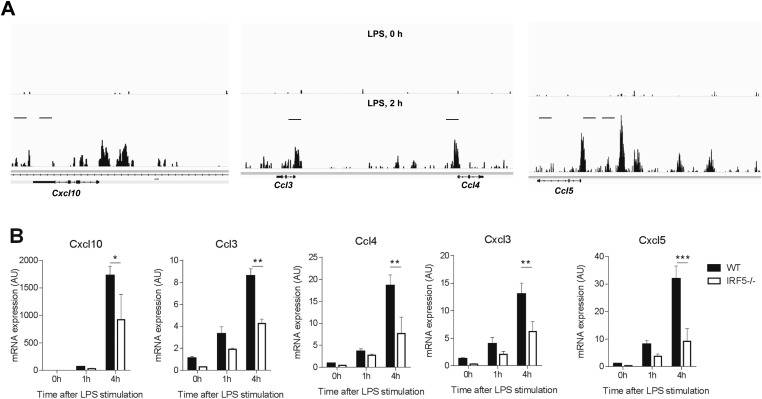

Fig. S5.

IRF5 controls chemokine network. (A) Representative UCSC (University of California, Santa Cruz) genome browser tracks in the Cxcl10, Ccl3, Ccl4, and Ccl5 loci for IRF5 binding peaks in unstimulated (LPS, 0 h) or LPS-stimulated (LPS, 2 h) GM-bone-marrow–derived macrophages/DCs (GM-BM-DC/MPHs). (B) CXCL10, CCL3, CCL4, CXCL3, and CXCL5 mRNA expression in the IRF5−/− and WT GM-BM-DC/MPHs stimulated with LPS for 0, 1, and 4 h using quantitative RT-PCR. Data shown are the mean and SEM derived from three mice from a representative experiment. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data shown are mean and SEM derived from five to six mice from a representative AIA experiment. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Statistical analysis was performed by one-tailed Mann–Whitney u test. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

We next examined mRNA expression of eight selected chemokines from the list in IRF5−/− and WT GM-BM-DC/MPHs stimulated with LPS for 1 and 4 h using quantitative RT-PCR. Expression of five of them, such as CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL10, CCL3, and CCL4, was significantly reduced in IRF5−/− macrophages (Fig. 4B and Fig. S5B). In addition, expression of two other chemokines known to be important for neutrophil trafficking, CXCL3 and CXCL5, was also significantly reduced (Fig. S5B). Moreover, we have previously shown that the expression of both IL-1α and IL-1β, which are potent chemoattractants for myeloid cells (28), is also under IRF5 control in GM-BM-DC/MPHs (27).

Hence, the combined global profiling of IRF5-bound sites and gene expression analysis in macrophages/DCs deficient in IRF5 have highlighted the direct role for IRF5 in transcriptional regulation of key chemokine genes and specifically, those involved in neutrophil trafficking.

Discussion

Neutrophil recruitment to the sites of infection has long been considered to be a key event in microbial clearance through their release of toxic molecules, including reactive oxygen species and also of cytokines and chemokines, which subsequently orchestrate the course of inflammation. Consequently, their removal from the site of inflammation is vital for maintaining host health. Here, we demonstrate that deficiency in transcription factor IRF5, which has been previously shown to modulate macrophage phenotype, also significantly reduces neutrophil trafficking to the sites of inflammation in various tissues. We unravel a systemic role for IRF5 in regulating chemokine gene expression in macrophages, including the expression of major neutrophil chemoattractants. Moreover, we discover that IRF5 is critical for the establishment of the MHCII+ phenotype in both steady-state macrophages of the knee joint and in monocyte-derived macrophages during antigen-induced arthritis.

Heterogeneity of tissue macrophages has been extensively analyzed in the last few years, with possible coexisting mechanisms of macrophage development from recruited blood monocytes and local self-renewal of tissue-resident macrophages, such as Kupffer cells, lung, peritoneal, and splenic macrophages, being described (11). However, the origin of synovial macrophages remained elusive until recently. Recent work by Misharin et al. using a series of elegant chimera experiments demonstrated that the synovial lining in the naïve mouse ankle joint contains a heterogeneous population of macrophages, with the majority being true tissue-resident cells (MHCII−) but about a fifth originating from the bone marrow (MHCII+) (14). Of interest, expression of CX3CR1 was mainly confined to MHCII− synovial macrophages, further suggesting that these cells originate prenatally. We have extended the characterization of synovial macrophages by demonstrating that in both ankle and knee joints, the population of MHCII+ macrophages is severely compromised in IRF5-deficient animals (Fig. 2). We also noted some differences between macrophage populations in the two joints analyzed. First, there appears to be a higher representation of MHCII+ macrophages in the knee than in the ankle. Second, MHCII− macrophages in the ankle express higher levels of IRF5 than those in the knee. Further detailed analysis, such as fate mapping, will be necessary to ultimately determine the origin of synovial macrophage populations in the knee.

In the K/BxN model of sterile inflammatory arthritis, circulating nonclassical (Ly6C−) blood monocytes are recruited to the joint and differentiate into classically activated inflammatory macrophages, driving joint pathology (14). In contrast, we find that in the AIA model, the majority of the infiltrating monocytes were Ly6Cint or Ly6Chi. Moreover, their recruitment was almost completely abolished in the mBSA-challenged joints of CCR2−/− mice that are deficient in circulating Ly6C+ monocytes (Fig. 2C). Thus, despite somewhat similar joint pathologies and large neutrophil influxes manifested at early stages, the two models clearly differ in the types of circulating monocytes recruited to the joint and hence in their pathogenesis. As demonstrated by a clear shift in Ly6C expression between the naïve and PBS control knees (Fig. 2D), the immunization with CFA composed of inactivated and dried mycobacteria is likely to predispose to preferential recruitment of classical monocytes to the site of inflammation. Of significance, in patients with RA, it is the intermediate CD14++CD16+ (corresponding to Ly6Cint in mouse) blood monocytes that appear to be significantly increased in patients with RA, whereas nonclassical CD14+CD16++ (Ly6C− in mouse) remained the same (29).

Mice lacking IRF5 demonstrate a shift toward type-2 immune response in a diet-induced model of obesity (30) and a pristane-induced model of lupus (31). In addition, in the pristine-induced lupus model, IRF5−/− monocytes show reduced migration and reduced expression of CCR2 and CXCR4 into the peritoneal cavity (32). However, this difference is not observed in the bone marrow, and monocytes egress normally into circulation. Moreover, the influx of Ly6Chi monocytes into the peritoneal cavity upon thioglycollate stimulation remains unaffected. Thus, the observed effect on monocyte migration and receptor expression appears to be specific to pristane injection rather than a general property of monocytes lacking IRF5. Our own data show that the influx of monocytes remains unaffected, both in the knee and in the lung (Fig. S1C).

Blocking neutrophil influx into the joints, either with Ly6G antibodies or by interfering with neutrophil migration e.g., by using a CXCR1/CXCR2 allosteric inhibitor, has been demonstrated to significantly reduce arthritis development in different mouse models of the disease, including AIA (33). Moreover, blockade of CXCL1, a CXCR2 ligand, with antibodies, led to a reduced number of neutrophils in the joint cavity of AIA mice (34), mimicking the effect of the IRF5 deletion observed in this study.

Macrophages, neutrophils, and epithelial cells can all secrete CXCL1 and promote neutrophil entry. However, in the inflamed arthritic knee, macrophages express the highest levels of IRF5, exceeding the IRF5 level detected in neutrophils by more than 10-fold [compare mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 1,344 ± 214 and 95 ± 33, P < 0.0001]. IRF5 expression was not detected in CD45 negative cells (used as a proxy for epithelial cells) of the knee. Moreover, no difference in the secretion of CXCL1 was observed between WT and IRF5−/− bone-marrow–derived neutrophils in response to a range of toll-like receptor agonists (13). We observe a significantly lower mRNA expression of CXCL1 by BM–derived DC/macrophages stimulated with LPS (Fig. 4). Taken together these data suggest that it is macrophage-specific production of CXCL1 and possibly other chemokines not detected by our assay or not tested that is likely to be affected most by the lack of IRF5. Our preliminary data using myeloid deleters, LysM-cre mice crossed with Irf5flox/flox mice, indicate that reduction of IRF5 expression in macrophages is responsible for the observed decrease in CXCL1 secretion. In future studies, we plan to further test this hypothesis by generating more specific ablations of IRF5 in macrophages and neutrophils.

Neutrophils display marked abnormalities in phenotype and function in autoimmune diseases, including RA, systemic vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (35), complementing macrophage alterations. In these conditions, neutrophils may play a central role in the initiation and perpetuation of aberrant immune responses and organ damage. Here we show that inhibition of IRF5 activity leads to reduction in neutrophil influx at the sites of acute inflammation. Thus, in addition to the previously suggested and recently confirmed role of IRF5 in balancing the arms of Th1/Th17 and Th2 adoptive immune responses (15, 30, 36), IRF5 also plays a direct role in controlling the innate immune responses leading to host tissue damage. These results augment the evidence suggesting that IRF5 blockade might be an effective therapeutic target. How to block IRF5 may not be easy, as transcription factors are often considered “nondruggable,” but perhaps other steps, such as the regulation of IRF5 activation by modifying enzymes might be more tractable. Such therapeutics would likely be useful in a very wide spectrum of diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

IRF5−/− mice were bred on a C57BL/6 background and their generation has been described previously (37). As a recent study identified a spontaneous mutation in some colonies of IRF5−/− mice, experimental animals were genotyped for a mutation in Dock2 (38); all mice used in this study were determined to be free of this homozygous mutation. CCR2−/− mice (B6.129S4-Ccr2tm1Ifc/J, JAX stock number 004999) were also bred on a C57BL/6 background. The experimental animal procedures used in this work were approved by the Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology Ethics Committee and the United Kingdom Home Office.

Antigen-Induced Arthritis.

We induced arthritis as described previously (17, 18). At 9 or 14 d, the mice were killed and the knee joints were excised and subjected to clinical and histological analyses. Spleen, blood, and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested occasionally in addition to knee joints. Single cells of knee, mediastinal lymph nodes, blood, or spleen were subjected to flow cytometry analysis. For further details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Acute Lung Injury.

Following short anesthesia with isofluorane, mice were administered LPS at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight intranasally. Mice were killed 24 h after the challenge, bronchoalveolar lavage was performed, and lavage fluid was collected. Afterward, the whole lung was harvested and both were used for further analyses.

Air Pouch.

Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and 3 mL of air was injected s.c. to create a dorsal air pouch with a top-up of air 3 d later. At 6 d after the creation of the air pouch, mice were challenged with 100 µg zymosan (Sigma) injected directly into the pouch. Animals were killed 4 h later and infiltrating cells were harvested from the air pouch.

In Vitro Bone-Marrow–Derived DC/Macrophages.

Bone marrow progenitors were differentiated into DC/macrophage cultures in vitro in the presence of recombinant murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL; Preprotech). For further details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Cytokine Detection.

Secreted cytokines in the cell supernatants and BAL were quantified using the Luminex bead-based assay (R&D Systems) following manufacturer’s instructions. Measurements were performed using a Luminex 100 analyzer (Luminex).

Neutrophil Migration.

For real-time analysis of migrating neutrophils, a 12-channel TAXIScan (23) was used with a 5-μm chip according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Effector Cell Institute). Sequential image data were generated from individual jpegs processed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health), equipped with the manual tracking and chemotaxis tool plugins (Ibidi). Euclidean distances refer to the total Euclidean distance traveled by individual cells in a particular experiment.

Cell Proliferation Assay.

Inguinal lymph nodes were harvested from immunized mice and cell suspensions were plated at 200,000–300,000 cells per well. Cells were stimulated with either α-CD3 (clone 145–2C11), mBSA antigen (50 µg/mL), or media alone (naïve) for 48 h at 37 °C. To determine proliferation, replicating DNA was stained using an EdU kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies). Briefly, EdU was added 2 h before the end of stimulation. Extracellular staining and flow cytometry were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from joints of mice or in vitro differentiated macrophages with an RNeasy Mini kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen) and cDNA was synthesized from total RNA with a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies). Gene expression was measured by the change-in-threshold (∆∆CT) method based on real-time PCR in an ABI 7900HT or ViiA7 with TaqMan primer sets (Life Technologies).

Statistical Analyses.

Statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad v6.0 (GraphPad Software) using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction (multiple comparisons) or Mann–Whitney tests (comparisons between two groups).

SI Materials and Methods

Antigen-Induced Arthritis.

We induced arthritis as described previously (18, 19). Briefly, at day 0, mice were sedated using inhaled isofluorane anesthesia and subsequently immunized with 100 µg of mBSA (Sigma) emulsified in 100 µL of complete Freund’s adjuvant (BD Difco), administered s.c. at the base of the tail. At day 7, we induced arthritis by means of an intraarticular injection of mBSA (200 µg in 10 µL of sterile PBS), or PBS alone using a sterile 33-gauge microcannula, in sedated animals. At 9 or 14 d, the mice were killed and the knee joints were excised. Spleen, blood, and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested occasionally in addition to knee joints.

Clinical and Histological Methods.

Arthritic knees were fixed in 10% (vol/vol) buffered formalin. Knees were decalcified in 10% (vol/vol) EDTA and dehydrated before embedding in paraffin wax. Coronal sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Joints were scored in a blinded manner for degree of joint space infiltrate, bone erosion, and synovial thickening. The inflammation score was based on joint space infiltrate. For immunohistochemical analysis, paraffin-embedded sections were stained with APC-conjugated Ly6G (clone 1A8; Biolegend) or isotype control and positive cells were viewed under fluorescence microscopy. Total cells/nuclei in the same section were stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, ProLong Gold; Life Technologies). IgG1 and IgG2a paired antibodies (R&D Systems) were used to measure serum antibody levels by ELISA.

Flow Cytometry.

Single cell suspensions of knees, mediastinal lymph nodes, blood, or spleen were suspended in FACS buffer (0.5% BSA, 0.02 N sodium azide in PBS, pH 7.4). To distinguish between live and dead cells, we used a viability dye (Life Technologies), followed by staining with antibodies against CD45 (clone 30-F11), CD11b (clone M1/70), F4/80 (clone BM8), Ly6C (clone AL-21), Ly6G/GR-1 (clone RB6-8C5), GR-1 (clone 1A8-Ly6g), CD64 (clone X54-5/7.1), CD11c (clone N418), MHCII (clone M5/114.15.2), CD206 (clone C068C2), CD19 (eBio1 D3), CD4 (clone RM4-5), and γδ TCR (clone eBioGL3). For intracellular FACS staining, cell suspensions were stimulated with a mixture of PMA (Merck), ionomycin (Merck), and Brefeldin A (Sigma) for T-cell cytokines and with LPS (Alexis Biochemicals), Brefeldin A, and Monensin (BD) for myeloid-derived cytokines. Following extracellular staining as above, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Foxp3 staining set (eBioscience) followed by staining with pro-IL1β (clone NJTEN3), IL17a (clone eBio17B7), and IFNγ (clone XMG1.2) antibodies. FACS analysis was performed using a FACS Canto II or Fortessa X-20 (BD), and the data were analyzed with FlowJo software, version 7.6 (Treestar).

In Vitro Bone-Marrow–Derived DC/Macrophages.

To generate in vitro differentiated DC/macrophages, bone marrow progenitors from wild-type and knockout mice were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with l-glutamine (PAA Laboratories) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 0.01% 2-mercaptoethanol, and with recombinant murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL; Preprotech). On day 3 of culture, fresh medium with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF was added to the plates. On day 6, half of the medium was removed from each plate and spun down. Cell pellets were then resuspended in fresh medium containing GM-CSF and added back to the culture plate. After 8 d, adherent and nonadherent cells were harvested, washed with PBS, replated, and then stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL; Alexis Biochemicals).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Fiona McCann and Kay McNamee for help with animal models. This work was supported by the Kennedy Institute Trustees Research Fund (M.W. and K.B.), American Asthma Foundation Early Excellence Award AAF 11-0105 (to I.A.U. and A.J.B.) and MRC Project Grant MR/J001899/1 (to I.A.U. and D.G.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1506254112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Helmick CG, et al. National Arthritis Data Workgroup Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tak PP, Bresnihan B. The pathogenesis and prevention of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis: Advances from synovial biopsy and tissue analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(12):2619–2633. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2619::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smeets TJ, et al. Analysis of the cell infiltrate and expression of matrix metalloproteinases and granzyme B in paired synovial biopsy specimens from the cartilage-pannus junction in patients with RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(6):561–565. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.6.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulherin D, Fitzgerald O, Bresnihan B. Synovial tissue macrophage populations and articular damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(1):115–124. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrera P, et al. Synovial macrophage depletion with clodronate-containing liposomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(9):1951–1959. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1951::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright HL, Moots RJ, Edwards SW. The multifactorial role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(10):593–601. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohr W, Westerhellweg H, Wessinghage D. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes in rheumatic tissue destruction. III. an electron microscopic study of PMNs at the pannus-cartilage junction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1981;40(4):396–399. doi: 10.1136/ard.40.4.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittkowski H, et al. Effects of intra-articular corticosteroids and anti-TNF therapy on neutrophil activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(8):1020–1025. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.061507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khandpur R, et al. NETs are a source of citrullinated autoantigens and stimulate inflammatory responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(178):178ra40. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray PJ, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: Nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41(1):14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sieweke MH, Allen JE. Beyond stem cells: Self-renewal of differentiated macrophages. Science. 2013;342(6161):1242974. doi: 10.1126/science.1242974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becher B, et al. High-dimensional analysis of the murine myeloid cell system. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(12):1181–1189. doi: 10.1038/ni.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ericson JA, et al. ImmGen Consortium Gene expression during the generation and activation of mouse neutrophils: Implication of novel functional and regulatory pathways. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e108553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misharin AV, et al. Nonclassical Ly6C(-) monocytes drive the development of inflammatory arthritis in mice. Cell Reports. 2014;9(2):591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krausgruber T, et al. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1-TH17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(3):231–238. doi: 10.1038/ni.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss M, Blazek K, Byrne AJ, Perocheau DP, Udalova IA. IRF5 is a specific marker of inflammatory macrophages in vivo. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:245804. doi: 10.1155/2013/245804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asquith DL, Miller AM, McInnes IB, Liew FY. Animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(8):2040–2044. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egan PJ, van Nieuwenhuijze A, Campbell IK, Wicks IP. Promotion of the local differentiation of murine Th17 cells by synovial macrophages during acute inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(12):3720–3729. doi: 10.1002/art.24075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsey MV, Tuder RM, Abraham E. Neutrophils are major contributors to intraparenchymal lung IL-1 beta expression after hemorrhage and endotoxemia. J Immunol. 1998;160(2):1007–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorner T, Lipsky PE. B cells: Depletion or functional modulation in rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(2):228–236. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savitsky DA, Yanai H, Tamura T, Taniguchi T, Honda K. Contribution of IRF5 in B cells to the development of murine SLE-like disease through its transcriptional control of the IgG2a locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(22):10154–10159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005599107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boring L, et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(10):2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nitta N, Tsuchiya T, Yamauchi A, Tamatani T, Kanegasaki S. Quantitative analysis of eosinophil chemotaxis tracked using a novel optical device: TAXIScan. J Immunol Methods. 2007;320(1-2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colville-Nash P, Lawrence T. Air-pouch models of inflammation and modifications for the study of granuloma-mediated cartilage degradation. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;225:181–189. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-374-7:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295(3):L379–L399. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helft J, et al. GM-CSF mouse bone marrow cultures comprise a heterogeneous population of CD11c(+)MHCII(+) macrophages and dendritic cells. Immunity. 2015;42(6):1197–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saliba DG, et al. IRF5:RelA interaction targets inflammatory genes in macrophages. Cell Reports. 2014;8(5):1308–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rider P, et al. IL-1α and IL-1β recruit different myeloid cells and promote different stages of sterile inflammation. J Immunol. 2011;187(9):4835–4843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossol M, Kraus S, Pierer M, Baerwald C, Wagner U. The CD14(bright) CD16+ monocyte subset is expanded in rheumatoid arthritis and promotes expansion of the Th17 cell population. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):671–677. doi: 10.1002/art.33418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalmas E, et al. Irf5 deficiency in macrophages promotes beneficial adipose tissue expansion and insulin sensitivity during obesity. Nat Med. 2015;21(6):610–618. doi: 10.1038/nm.3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y, et al. Pleiotropic IFN-dependent and -independent effects of IRF5 on the pathogenesis of experimental lupus. J Immunol. 2012;188(8):4113–4121. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Feng D, Bi X, Stone RC, Barnes BJ. Monocytes from Irf5-/- mice have an intrinsic defect in their response to pristane-induced lupus. J Immunol. 2012;189(7):3741–3750. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coelho FM, et al. The chemokine receptors CXCR1/CXCR2 modulate antigen-induced arthritis by regulating adhesion of neutrophils to the synovial microvasculature. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(8):2329–2337. doi: 10.1002/art.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grespan R, et al. CXCR2-specific chemokines mediate leukotriene B4-dependent recruitment of neutrophils to inflamed joints in mice with antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(7):2030–2040. doi: 10.1002/art.23597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan MJ. Role of neutrophils in systemic autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):219. doi: 10.1186/ar4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng D, et al. Irf5-deficient mice are protected from pristane-induced lupus via increased Th2 cytokines and altered IgG class switching. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(6):1477–1487. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takaoka A, et al. Integral role of IRF-5 in the gene induction programme activated by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;434(7030):243–249. doi: 10.1038/nature03308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purtha WE, Swiecki M, Colonna M, Diamond MS, Bhattacharya D. Spontaneous mutation of the Dock2 gene in Irf5-/- mice complicates interpretation of type I interferon production and antibody responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(15):E898–E904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118155109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.