Abstract

Background

Behr’s syndrome is a classical phenotypic description of childhood-onset optic atrophy combined with various neurological symptoms, including ophthalmoparesis, nystagmus, spastic paraparesis, ataxia, peripheral neuropathy and learning difficulties.

Objective

Here we describe 4 patients with the classical Behr’s syndrome phenotype from 3 unrelated families who carry homozygous nonsense mutations in the C12orf65 gene encoding a protein involved in mitochondrial translation.

Methods

Whole exome sequencing was performed in genomic DNA and oxygen consumption was measured in patient cell lines.

Results

We detected 2 different homozygous C12orf65 nonsense mutations in 4 patients with a homogeneous clinical presentation matching the historical description of Behr’s syndrome. The first symptom in all patients was childhood-onset optic atrophy, followed by spastic paraparesis, distal weakness, motor neuropathy and ophthalmoparesis.

Conclusions

We think that C12orf65 mutations are more frequent than previously suggested and screening of this gene should be considered not only in patients with mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiencies, but also in inherited peripheral neuropathies, spastic paraplegias and ataxias, especially with pre-existing optic atrophy.

Keywords: Behr’s syndrome, mitochondrial translation, optic atrophy, spastic paraplegia, peripheral neuropathy, ataxia

INTRODUCTION

First described by Carl Behr in 1909, classical Behr’s syndrome (MIM 210000) comprises childhood-onset optic atrophy combined with various neurological symptoms including ophthalmoparesis, nystagmus, spastic paraparesis, ataxia, peripheral neuropathy and a variable degree of learning difficulties [1, 2]. While the optic atrophy in these patients remains stable, other neurological signs progress during childhood becoming more prominent in the second or third decade. The majority of early cases are sporadic or show autosomal recessive inheritance, but some families have an autosomal dominant disorder, suggesting genetic heterogeneity [3].

Autosomal recessive OPA3 mutations have been identified in Iraqi Jews presenting with Behr’s syndrome and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (Costeff syndrome) [4, 5] and more recently autosomal dominant OPA1 mutations were shown in Behr’s syndrome without metabolic abnormalities [6]. However the classical phenotype reported by Behr was most likely due to a different genetic cause.

Here, we describe 4 patients from 3 families with classical Behr’s syndrome and autosomal recessive mutations in the C12orf65 gene, encoding a mitochondrial protein involved in mitochondrial translation [7].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case reports

This study had institutional and ethical review board approval. All of the patients gave informed consent for the study and for showing their photographs.

Patient 1, a 13 year-old (y) boy and patient 2, his 7y sister were born to non-consanguineous Irish parents. Patient 1 had normal early development, and the first symptom was optic atrophy at 5y, followed by initially focal and asymmetric weakness and atrophy of the right arm and leg. These symptoms extended to the other side with spasticity, and he developed mild ataxia and learning difficulties. Currently, at age 13y he attends a special school and is able to walk independently with bilateral splints.

Detailed metabolic work-up (acyl-carnitines, urinary organic acids, 3-methylglutaconic acid, very long chain fatty acids, phytanic acid, vitamins E, A, B12, AFP, serum electrophoresis, lipoproteins, lysosomal enzymes, copper, ceruloplasmin, ferritin, iron) was normal. Electrophysiology detected signs of anterior horn cell lesion localized to the C8/T1 region. MRI showed high signal intensities in the periaqueductal grey matter in the mid brain at age 9 (Fig. 1D), but was normal at 10y.

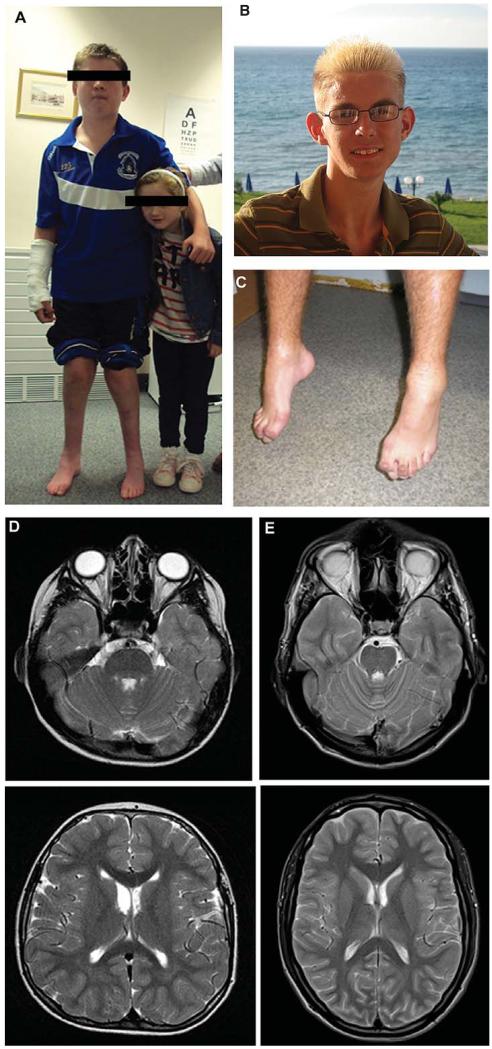

Fig. 1.

Clinical presentation and brain MRI of patients carrying homozygous nonsense mutations in the C12orf65 gene. Patient 1 and 2 (A), patient 3 (B), patient 4 (C), brain MRI of patients 1 (D) and 3 (E) detected bilateral, symmetric hyperintensities in the posterior pons and medullary region.

Muscle biopsy taken at the age of 10y revealed mitochondrial myopathy and deficiencies of multiple respiratory chain (RC) enzymes I, II/III and IV, associated with a low mtDNA copy number (~10% normal values) in this tissue. No mtDNA deletions were detected in muscle DNA. Direct sequencing of the OPA1, TK2, RRM2B and PEO1 genes revealed no candidate pathogenic mutations.

On clinical examination at 13y he had hypertelorism and broad nasal bridge (Fig. 1A). He had bilateral optic atrophy (6/36 on both eyes), ophthalmoparesis, bilateral nystagmus and slow saccades, bilateral facial weakness and a slightly slurred speech. He had significant spasticity and deep tendon reflexes were pathologically increased. There was muscle wasting and weakness in the hands, with bilateral foot drop and deformed feet (Fig. 1A). He had mild dysmetria and a wide-based, slightly ataxic gait.

Patient 2, his younger sister (Fig. 1A) had optic atrophy since 6y, followed by mild foot weakness and balance problems, but attends a mainstream school at 7y. Brain MRI and MRS were normal at 6y. On neurological examination at 7y she had a broad nasal bridge, bilateral optic atrophy, ophthalmoparesis and slow saccades. She had slightly brisk deep tendon reflexes and a very subtle spasticity in the legs. Proximal muscle power was preserved, but she could not walk on heels or tiptoes. She had a slightly ataxic gait.

Patient 3 is a 22 year-old man from Northern England (Fig. 1B), second child of healthy, non-consanguineous parents, born after uneventful pregnancy with normal delivery. Early motor milestones were normal, except for tiptoe walking, and he developed visual problems at 5y. He complained of aches in his legs and of problems with his gait. He also had learning difficulties with poor concentration and memory.

Metabolic studies were normal, CK was slightly increased (379 U/L, normal 40–320). CSF was normal. Brain MRI at age 6y was normal, but detected bilateral, symmetric hyperintensities in the posterior pons and medullary region at 14y and 22y, resembling Leigh’s disease (Fig. 1E). Electrophysiology at age 11y showed widespread lower motor neuron lesion.

Muscle biopsy at the age of 10y revealed several cytochrome c oxidase (COX)-deficient fibers following histochemical analysis and biochemical evidence of complex IV deficiency at 40% of control values; the activities of complexes I, II and III were all normal. Direct sequencing of the OPA1 gene revealed no candidate pathogenic mutations whilst mtDNA rearrangements were also excluded in muscle.

Clinical examination at age 22y revealed bilateral optic atrophy (4/60 bilaterally) but normal eye movements. He had spasticity and bilaterally increased deep tendon reflexes with positive Babinski sign, but absent ankle jerks. He had severely atrophic muscles in the arms and legs with distal predominance and foot drop, and needed bilateral splints. He had no sensory or vegetative symptoms and no ataxia. He had mild intellectual disability.

Patient 4 is a 16 year-old boy, one out of four children of non-consanguineous healthy parents of Hungarian Roma ethnic origin. The other 3 siblings are healthy. His early motor development was normal, however at 1y he started to walk on tiptoes and his gait was clumsy. At 5y he developed visual impairment and increasing clumsiness. He developed bilateral foot drop and foot deformity (Fig. 1C) and his gait became increasingly difficult over the last 11 years. He has slight learning difficulties. Electrophysiology could not detect motor and sensory responses in the legs, EMG showed neurogenic atrophy. Brain MRI was normal at 15y.

Clinical examination at age 16y showed bilateral optic atrophy with visual acuities of 0.2 and 0.5 in the right and left eye, respectively and slight nystagmus. There was a marked spasticity with distal weakness and atrophy on the lower limbs with significant foot deformity (Fig. 1). Deep tendon reflexes were increased, except for absent ankle jerks. He had a spastic-ataxic gait with foot-drop. A diagnostic muscle biopsy was not performed in this case.

Molecular genetics

Whole exome sequencing was performed in genomic DNA of patients 1, 2 and 3 and direct sequencing of C12orf65 was performed in patient 4 based on the clinical phenotype. DNA was isolated from lymphocytes (DNeasy®, Qiagen, Valencia, CA), fragmented and enriched by Illumina TruSeq™ 62 Mb exome capture, and sequenced (Illumina HiSeq 2000, 100 bp paired-end reads). The in-house bioinformatics pipeline included alignment to the human reference genome (UCSC hg19), reformatting, and variant detection (Varscan v2.2, Dindel v1.01), as described previously [8]. On-target variant filtering excluded those with minor allele frequency greater > 0.01 in several databases: dbSNP135, 1000 genomes (February 2012 data release), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI, NIH, Bethesda, MD) Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) 6500 exomes, and 343 unrelated in-house controls. Rare homozygous and compound heterozygous variants were defined, and protein altering and/or putative ‘disease causing’ mutations, along with their functional annotation, were identified using ANNOVAR [9]. Candidate genes were prioritized if previously associated with a disease phenotype [10]. Putative pathogenic variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing using custom-designed primers (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) on an ABI 3130XL (Life Technologies, CA), allowing segregation analyses where possible. The following primers were used for genomic DNA analysis of C12orf65 (NM 152269): exon 2: forward: 5′ GCATAATCTTGAGGGCAGATG-3′, reverse: 5′-GGCCCAAGCCAGAAAAATA-3′, exon 3: forward: 5′-GCGAACAGGTTGAATTTAATGA-3′, reverse: 5′-CACTATAATAATGCTGGTGATGGA-3′.

Direct Sanger sequencing of the cDNA of C12orf65 was performed in patient 4 with the following primers: forward: 5′- GCAACCAACAAAACCAGCAA-3′ and reverse: 5′- CAGGACTGTTTTCACCATTGTAG-3′.

Cell culture

Fibroblast cell cultures of two patients and controls were obtained from the Biobank of the Medical Research Council, Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases, Newcastle. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Fibroblasts were grown in high glucose Dulbeccos modified Eagle’s medium (Sigma, Poole, UK) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum.

Oxygen consumption was measured using Seahorse Bioscience XFe96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA, USA) as previously described [11] with some modifications. Briefly, 3×104 cells/well were seeded in 24 wells per cell line, the day after oxygen consumption rate (OCR), leaking respiration (LR), maximal capacity respiration (MCR) and not electron transport chain respiration (NMR) were determined by adding 1 μM oligomycin (LR), carbonyl cyanide-ptrifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) (MCR: 2 injections of 0.5 μM and 1 μM, respectively) and 1 μM Rotenone/antimycin (NMR), respectively. The data was corrected by the NMR and expressed as pmol of oxygen/min/mg of protein. The quantity of protein was measured by Bradford method.

RESULTS

DNA analysis, whole exome sequencing

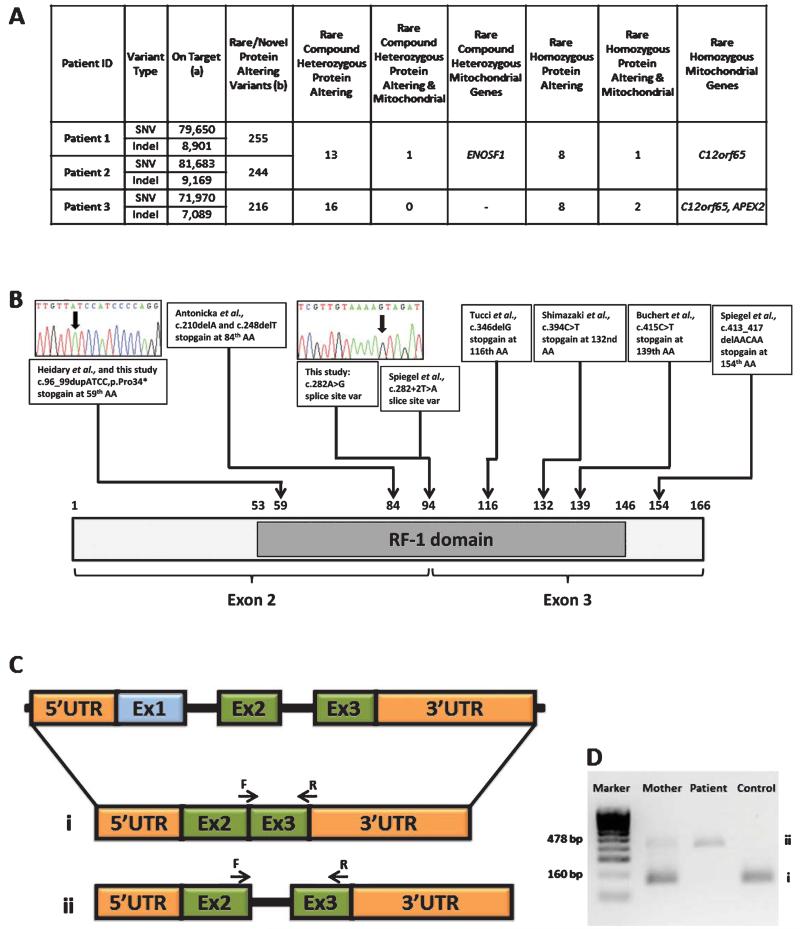

Coverage and depth statistics for the exome sequencing are reported in Fig. 2A and Table 2. The variants in ENOSF1 and APEX2 did not segregate with the disease in the family. The same homozygous truncating mutation in C12orf65 (c.96_99dupATCC predicting p.Pro34Ilefs*25) was detected in Patients 1–3 (Table 1). The mutation segregated with the disease in each family, was not detected in 190 ethnically-matched control alleles, and is predicted to cause a complete loss of the C12orf65 protein. A homozygous c.282 G>A variant (predicting p.Lys94Lys) was detected in Patient 4. This mutation affects the last codon of exon 2, and results in the loss of a splice site with retention of intron 2 (Fig. 2). Unaffected family members were heterozygous for the c.282 G>A variant which was not detected in 200 Hungarian Roma alleles. Additional screening of the C12orf65 gene in 29 patients with optic atrophy and additional neurological symptoms detected no pathogenic mutations.

Fig. 2.

A: Exome coverage and depth statistics. (a) Variants with position within targets (Illumina Truseq 62 Mb)+/−500 bp, seen on both (Forward & Reverse) strands and (SBVs only) variant allele frequency > 24%, (b) Rare/novel variants (homozygous MAF < 0.01, compound heterozygous MAF product < 0.0001 and single heterozygous MAF < 0.001) with exclusion of common variants found to be shared in an in-house panel of 394 individuals, 1000 Genomes and NHLBI-ESP 6500 databases. B: Schematic structure of C12orf65, showing the localisation of the RF-1 domain, position of identified mutations and the exon structure. Exome sequencing identified pathogenic C12orf65 mutations in 4 patients. C: Schematic structure of C12orf65 cDNA showing the splice defect (ii) caused by the c.282 G>A mutation in Patient 4. D: Agarose gel showing the amplification of cDNA in patient 4 and in his mother, i) normal splicing producing a 160 bp product, ii) mutation causing intron 2 to be retained giving a larger band of 478 bp.

Table 2.

Coverage calculated to Consensus Coding Sequence (CCDS) bases (31,935,069 bp) and depth statistics

| ID | Mean per CCDS base depth |

Min Depth |

Max Depth |

Number CCDS bases covered 20-fold |

% CCDS bases covered 20-fold |

Number CCDS bases covered 10-fold |

% CCDS bases covered 10-fold |

Number CCDS bases covered 5-fold |

% CCDS bases covered 5-fold |

Number CCDS bases covered 1-fold |

% CCDS bases covered 1-fold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 101.2 | 0 | 4875 | 29308867 | 91.8 | 30194781 | 94.6 | 30615203 | 95.9 | 31152641 | 97.5 |

| P2 | 113.0 | 0 | 5404 | 29536224 | 92.5 | 30232962 | 94.7 | 30595896 | 95.8 | 31113372 | 97.4 |

| P3 | 80.6 | 0 | 6868 | 28496667 | 89.2 | 30570340 | 95.7 | 31044392 | 97.2 | 31378906 | 98.3 |

Table 1.

Clinical summary of Patients 1–4 reported in this study and the previously reported patients carrying pathogenic mutations in C12orf65

| Clinical presentation of patients presented in this study |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset/alive or died† |

Optic atrophy |

Neuropathy | Pyramidal signs |

Ophthalmoparesis | Ataxia | Cognitive dysfunction |

Biochemical markers |

Mutation | |

| Patient 1 | 5y/13y | +(5y) | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | Complex I, II/III, IV defect in muscle | Homozygous p.Pro34Ilefs*25 |

| mtDNA depletion(10% of normal) | |||||||||

| Patient 2 | 6y/7y | +(6y) | + | + | + | + | − | n.d. | |

| Patient 3 | 6y/22y | +(6y) | +++ | ++ | − | − | + | Complex IV defect in muscle | Homozygous p.Pro34Ilefs*25 |

| mtDNA depletion(10% of normal) | |||||||||

| Patient 4 | 5y/16y | +(5y) | +++ | ++ | − | + | + | n.d. | Homozygous c.282 G>A (splice site alteration) |

|

| |||||||||

| Clinical presentation of previously reported patients |

|||||||||

| Antonicka et al. P1 | 1y/8y† | ++(5y) | ? | ? | ++ | ++ | + | Complex I, IV, V defect in fibroblasts | Homozygous p.Val83Glyfs*1 |

| Antonicka et al., P2 | 15 m/20y | + | ++ | − | ++ | ? | ? | n.d. | Homozygous p.Gly72Alafs*12 |

| Antonicka et al., P3 | 3y/22y† | +(3y) | ++ | ? | ++ | − | ? | n.d. | |

| Shimazaki et al., P1 | 7y/32y | +(7y) | + | + | − | − | − | Complex I, IV defect in fibroblasts | Homozygous p.Arg132* |

| Shimazaki et al., P2 | 7y/42y | +(7y) | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | n.d. | |

| Buchert et al., P1 | ?/27y | − | +deformed hands, feet | ? | + | ? | + | n.d. | Homozygous p.Gln139* |

| Buchert et al., P2 | ?/24y | − | ? | ? | + | ? | + | n.d. | |

| Tucci et al., P1 | 8y/34y | + | + | + | + | ? | + | n.d. | Homozygous p.Val1 16* mutation |

| Tucci et al., P2 | childhood/53y | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | n.d. | |

| Tucci et al., P3 | childhood/51y | + | + | + | ? | ? | + | Complex V defect in lymphoblasts, mitochondrial membrane potential↓ | |

| Heidary et al., P1 | childhood/8y | + | ? | + | + | + | + | Complex IV defect in muscle | Compound heterozygous p.Pro34Ilefs*25 and p.Gly72Alafs*12 |

| Heidary et al., P2 | childhood/5y† | + | ? | + | + | + | + | Complex IV defect in muscle | |

| Spiegel et al., F1 | childhood/? | + | + | + | − | − | − | n.d. | Homozygous p.Lys138Argfs*16 |

| Spiegel et al., F2 | childhood/? | + | + | + | − | − | + | Complex I and IV deficiency in muscle | Homozygous c.282+ 2T>A (splice site alteration) |

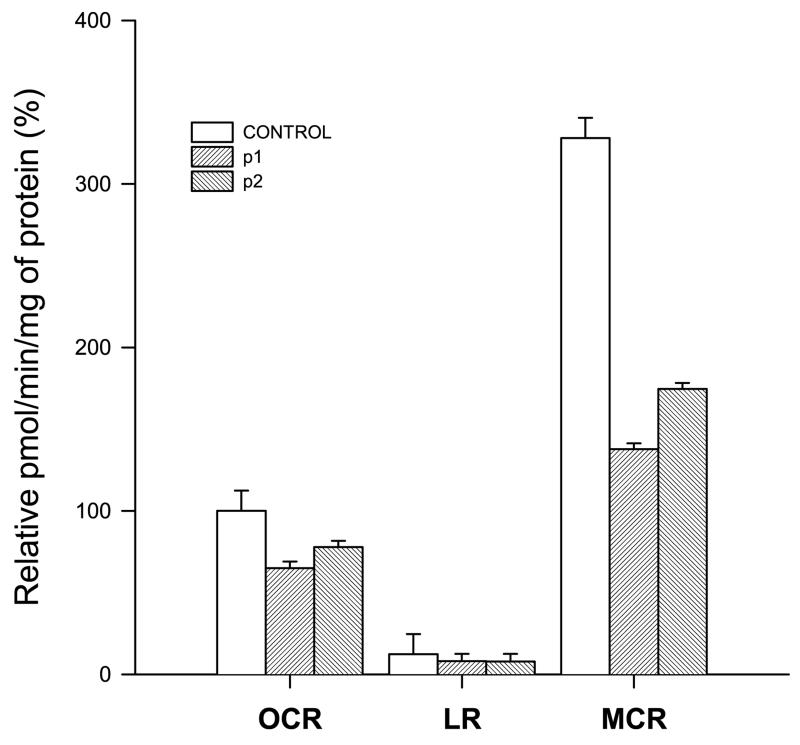

Electron transport chain capacity

The Seahorse XF96 extracellular flux analyzer was used to measure oxygen consumption as a marker of the electron transport chain (ETC) capacity. As shown in Fig. 3, the patient cell lines showed a decrease in OCR when compared to controls. This difference is notably bigger after treating the cells with FCCP, an ETC accelerator which acts as an uncoupling agent transporting hydrogen ions the inner mitochondrial membrane, showing a clear ETC defect in the patient cell lines.

Fig. 3.

Oxygen consumption in fibroblasts, white and stripped bars represent the mean values from controls (C1 and C2) and patients (P1 and P2), respectively. Corrected oxygen consumption by the non mitochondrial respiration and mg of protein is represented as oxygen consumption rate (OCR), leaking respiration (LR) and maximal capacity respiration (MCR), respectively. The mean value for OCR respiration in control fibroblasts has been set to 100%. OCR: Controls, 100.0 ± 3.38% (2); P1, 64.9 ± 7.06% (24); P2, 77.82 ± 12.41% (24) LR: Controls, 12.24 ± 3.54% (2); P1, 8.15 ± 7.66% (24); P2, 12.70 ± 19.54% (24) MCR: Controls, 327.97 ±48.93% (2); P1, 137.70 ± 21.11% (24); P2, 174.63 ± 27.14% (24). p values are shown in the figure.

DISCUSSION

C12orf65 belongs to a family of four mitochondrial class I peptide release factors including mtRF1a, mtRF and ICT1, which are characterized by the presence of a conserved Gly-Gly-Gln (GGQ) motif. From this group of genes only C12orf65 has been associated to date with human disease. However, C12orf65 does not exhibit peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase activity, but may play a role in recycling abortive peptidyl –tRNA species, released from the ribosome during the elongation phase of translation [7]. Down-regulation of C12orf65 resulted in significant changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial mass, indicating that it is essential for cell vitality and mitochondrial function [12].

The first report on mutations in the C12orf65 gene described 3 patients from 2 families with failure to thrive, nystagmus, ophthalmoparesis and psychomotor retardation in the second year of life and optic atrophy from 5–7y [7]. In the following years all 3 patients developed complex neurological symptoms including facial weakness, swallowing difficulties, motor neuropathy, gastrointestinal and respiratory problems, leading to severe disability (at 20y) or death at age 8 and 22y respectively. MRI signs were suggestive of Leigh syndrome, although the progression of symptoms has been slower, than in other forms of Leigh’s disease [7].

Recently some further papers have reported patients with mutations in C12orf65. Two siblings, carrying a p.Arg132* nonsense mutation, presented at age 7y with optic atrophy, followed by leg weakness, foot drop and spasticity. Investigation at 32y and 42y of age showed bilateral optic atrophy, spastic paraparesis and additional signs of motor neuropathy [13]. Another sibling pair with a homozygous p.Gln139* C12orf65 truncating mutation were reported with mild intellectual disability, spastic paraplegia and strabismus with dysmorphic features such as low set eye-brows [14], although the neurological description of these patients was limited. More recently a homozygous p.Val116* truncating mutation has been reported in 3 members of a large consanguineous Indian family with motor neuropathy and optic atrophy as characteristic signs of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) type 6 [15]. Furthermore, compound heterozygous (p.Pro34Ilefs*25 and p.Gly72*) frameshift mutations were present in 2 siblings who presented with optic atrophy and mild developmental delay and developed bilateral, symmetric lesions in the brainstem reminiscent of Leigh syndrome [16]. Two further homozygous mutations (p.Lys138Argfs*16 and c.282 + 2T>A) have been reported very recently in consanguineous families with childhood-onset optic atrophy accompanied by slowly progressive peripheral neuropathy and spastic paraparesis [17]. Most previous reports can conclusively (in hindsight) also be diagnosed as Behr’s syndrome except for the 2 patients in whom no neurological and ophthalmological examinations were noted [14].

Here we show 2 different homozygous C12orf65 nonsense mutations in 4 patients with a homogeneous clinical presentation matching the original historical description of Behr’s syndrome [1]. The first symptom in all patients was childhood-onset optic atrophy, followed by spastic paraparesis, distal weakness and motor neuropathy. Ophthalmoparesis, facial weakness and mild ataxia were also present, which symptoms could be explained by the periaqueductal brainstem lesion (Fig. 2). These findings show that although C12orf65 was thought to be associated with a “classical” mitochondrial Leigh syndrome, hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG55) or complicated CMT (CMT6), a detailed re-analysis of the phenotypes described in these previous reports revealed that all may be compatible with Behr’s syndrome.

Our study of three independent families with Behr’s syndrome strongly suggests that C12orf65 is an important causative gene that underlies this distinct clinical phenotype.

The clinical presentation of C12orf65 mutations is different from other genetic forms of Behr’s syndrome. Autosomal recessive OPA3 mutations have been identified in patients presenting with 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, optic atrophy and/or choreoathetoid movement disorder with onset before 10 years of age (Costeff syndrome) and spastic paraparesis, mild ataxia and occassional mild cognitive deficit may only develop later in the second decade [4, 5]. Autosomal dominant OPA1 mutations may only occassionally present as Behr’s syndrome [6], and although the optic atrophy is usually the first symptom, other neurological signs may not develop at all or appear only in adult age [18]. We suggest that the classical phenotype reported by Behr was most likely due to mutations in the C12orf65 gene, and this genetic cause is the most frequent cause of Behr’s syndrome in patients of different ethnic origin.

As an unexpected finding we detected low mtDNA copy number, but no mtDNA deletions in skeletal muscle of 1 patient. No data are available about mtDNA copy number analysis in any other previously reported patients. The presence of mtDNA depletion in muscle DNA of patient 1 is intriguing. It may reflect down-regulation of the mitochondrial mass, and it is also possible that the primary molecular defect in C12orf65 causes the combined respiratory chain defect at least in part through an effect on mtDNA copy number. Further studies are required to confirm this observation in additional cases.

In summary, Behr’s syndrome due to C12orf65 mutations is a clinically recognizable disease presentation and should be considered not only in multiple mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiencies, but also in the differential diagnosis of inherited peripheral neuropathies, spastic paraplegias and ataxias, especially with pre-existing optic atrophy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

RH was supported by the Medical Research Council (UK) (G1000848) and the European Research Council (309548). PFC is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Clinical Science and an NIHR Senior Investigator who also receives funding from the Medical Research Council (UK), the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society, and the UK NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ageing and Age-related disease award to the Newcastle upon Tyne Foundation Hospitals NHS Trust. PYWM is an MRC Clinician Scientist. RWT receives support from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Mitochondrial Research (096919Z/11/Z) and the UK NHS Highly Specialised “Rare Mitochondrial Disorders of Adults and Children” Service. We are grateful to the Medical Research Council (MRC) Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases Biobank Newcastle for supporting this project. This work made use of data and samples generated by the 1958 Birth Cohort (NCDS). Access to these resources was enabled via the 58READIE Project funded by Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council (grant numbers WT095219MA and G1001799). A full list of the financial, institutional and personal contributions to the development of the 1958 Birth Cohort Biomedical resource is available at http://www2.le.ac.uk/projects/birthcohort.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- [1].Behr C. Die komplizierte, hereditär-familiäre Optikusatrophie des Kindesalters: Ein bisher nicht beschriebener Symptomkompleks. Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde. 1909;47:138–160. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thomas PK, Workman JM, Thage O. Behr’s syndrome. A family exhibiting pseudodominant inheritance. J Neurol Sci. 1984;64:137–148. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(84)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Felicio AC, Godeiro-Junior C, Alberto LG, Pinto AP, Sallum JM, Teive HG, Barsottini OG. Familial Behr syndrome-like phenotype with autosomal dominant inheritance. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008;14:370–372. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sheffer RN, Zlotogora J, Elpeleg ON, Raz J, Ben-Ezra D. Behr’s syndrome and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:494–497. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71864-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Anikster Y, Kleta R, Shaag A, Gahl WA, Elpeleg O. Type III 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (optic atrophy plus syndrome, or Costeff optic atrophy syndrome): Identification of the OPA3 gene and its founder mutation in Iraqi Jews. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1218–1224. doi: 10.1086/324651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Marelli C, Amati-Bonneau P, Reynier P, Layet V, Layet A, Stevanin G, Brissaud E, Bonneau D, Durr A, Brice A. Heterozygous OPA1 mutations in Behr syndrome. Brain. 2011;134:e169. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq306. author reply e170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Antonicka H, Ostergaard E, Sasarman F, Weraarpachai W, Wibrand F, Pedersen AM, Rodenburg RJ, van der Knaap MS, Smeitink JA, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM, Shoubridge EA. Mutations in C12orf65 in patients with encephalomyopathy and a mitochondrial translation defect. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Horvath R, Holinski-Feder E, Neeve VC, Pyle A, Griffin H, Ashok D, Foley C, Hudson G, Rautenstrauss B, Nürnberg G, Nürnberg P, Kortler J, Neitzel B, Bäassmann I, Rahman T, Keavney B, Loughlin J, Hambleton S, Schoser B, Lochmüller H, Santibanez-Koref M, Chinnery PF. A new phenotype of brain iron accumulation with dystonia, optic atrophy, and peripheral neuropathy. Mov Disord. 2012;27:789–793. doi: 10.1002/mds.24980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from next-generation sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lieber DS, Calvo SE, Shanahan K, Slate NG, Liu S, Hershman SG, Gold NB, Chapman BA, Thorburn DR, Berry GT, Schmahmann JD, Borowsky ML, Mueller DM, Sims KB, Mootha VK. Targeted exome sequencing of suspected mitochondrial disorders. Neurology. 2013;80:1762–1770. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918c40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Invernizzi F, D’Amato I, Jensen PB, Ravaglia S, Zeviani M, Tiranti V. Microscale oxygraphy reveals OXPHOS impairment in MRC mutant cells. Mitochondrion. 2012;12:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kogure H, Hikawa Y, Hagihara M, Tochio N, Koshiba S, Inoue Y, Güntert P, Kigawa T, Yokoyama S, Nameki N. Solution structure and siRNA-mediated knockdown analysis of the mitochondrial disease-related protein C12orf65. Proteins. 2012;80:2629–2642. doi: 10.1002/prot.24152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shimazaki H, Takiyama Y, Ishiura H, Sakai C, Matsushima Y, Hatakeyama H, Honda J, Sakoe K, Naoi T, Namekawa M, Fukuda Y, Takahashi Y, Goto J, Tsuji S, Goto Y, Nakano I. A homozygous mutation of C12orf65 causes spastic paraplegia with optic atrophy and neuropathy (SPG55) J Med Genet. 2012;49:777–784. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Buchert R, Uebe S, Radwan F, Tawamie H, Issa S, Shimazaki H, Henneke M, Ekici AB, Reis A, Abou Jamra R. Mutations in the mitochondrial gene C12ORF65 lead to syndromic autosomal recessive intellectual disability and show genotype phenotype correlation. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56:599–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tucci A, Liu YT, Preza E, Pitceathly RD, Chalasani A, Plagnol V, Land JM, Trabzuni D, Ryten M, on behalf of UKBEC. Jaunmuktane Z, Reilly MM, Brandner S, Hargreaves I, Hardy J, Singleton AB, Abramov AY, Houlden H. Novel C12orf65 mutations in patients with axonal neuropathy and optic atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013 Nov 6; doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306387. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Heidary G, Calderwood L, Cox GF, Robson CD, Teot LA, Mullon J, Anselm I. Optic Atrophy and a Leigh-Like Syndrome Due to Mutations in the C12orf65 Gene: Report of a Novel Mutation and Review of the Literature. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34:39–43. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Spiegel R, Mandel H, Saada A, Lerer I, Burger A, Shaag A, Shalev SA, Jabaly-Habib H, Goldsher D, Gomori JM, Lossos A, Elpeleg O, Meiner V. Delineation of C12orf65-related phenotypes: A genotype-phenotype relationship. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014 Jan 15; doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.284. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths PG, Gorman GS, Lourenco CM, Wright AF, Auer-Grumbach M, Toscano A, Musumeci O, Valentino ML, Caporali L, Lamperti C, Tallaksen CM, Duffey P, Miller J, Whittaker RG, Baker MR, Jackson MJ, Clarke MP, Dhillon B, Czermin B, Stewart JD, Hudson G, Reynier P, Bonneau D, Marques W, Jr, Lenaers G, McFarland R, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM, Votruba M, Zeviani M, Carelli V, Bindoff LA, Horvath R, Amati-Bonneau P, Chinnery PF. Multi-system neurological disease is common in patients with OPA1 mutations. Brain. 2010;133:771–86. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]