Through the wonders of fermentation, simple sugars derived from enzymatic degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose in the plant cell wall are converted to the biofuel cellulosic ethanol, an attractive alternative to fossil fuels and grain-derived ethanol (Solomon et al., 2007). Before this fermentation takes place, however, the rigid lignin network in the cell wall must be loosened with hot acids or other vigorous pretreatment methods. Unfortunately, these expensive processes can produce fermentation-inhibiting byproducts. Lignin is a complex, diverse group of polymers formed by the oxidative polymerization of hydroxycinnamyl alcohol (monolignol) derivatives. Lignin contains monomethoxylated guaiacyl (G) subunits derived from coniferyl alcohol (which have the most stable linkages) and dimethoxylated syringyl (S) subunits derived from sinapyl alcohol, as well as small amounts of p-hydroxyphenyl (H) subunits and molecules related to monolignol biosynthesis, such as hydroxycinnamaldehydes and hydroxycinnamic acids. The composition of lignin varies widely based on plant species and subunit availability. Lignin polymerization is a simple chemical process with unparalleled metabolic flexibility, making lignin biosynthesis a promising target for manipulation: Altering lignin composition and content in biofuel crops may increase cell wall digestibility, leading to more efficient cellulosic ethanol production.

Two major strategies have been used to accomplish this task. First, increasing the S-to-G ratio by altering lignin biosynthesis-related gene expression can make the cell wall somewhat easier to degrade. For example, Arabidopsis thaliana plants overexpressing FERULATE 5-HYDROXYLASE (F5H), which functions in the rate-limiting step of syringyl lignin biosynthesis, contain lignin enriched in S subunits, while F5H-deficient ferulic acid hydroxylase1 (fah1) mutants contain high-G lignin. Second, downregulating genes encoding (hydroxy)cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), which catalyzes the last stage in lignin biosynthesis, generates plants with unusual lignin polymers that are sometimes less recalcitrant than standard lignin. However, such changes are often accompanied by dwarfing and, hence, reduced yields (Bonawitz and Chapple, 2013). Understanding why dwarfing occurs and the limitations of these strategies would greatly enhance efforts to overcome cell wall recalcitrance.

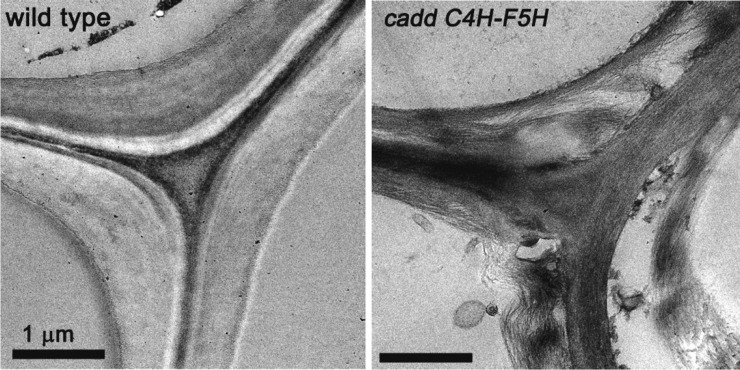

Recently, Anderson et al. (2015) came close to doing just that. First, they crossed the Arabidopsis cadc and cadd mutants, which have drastically altered lignin composition, with the fah1 mutant (high G) and an F5H-overexpressing transgenic line (C4H-F5H; high S). Most resulting mutants displayed wild-type growth, whereas cadd C4H-F5H plants were dwarfed, and cadc cadd C4H-F5H plants were severely dwarfed, even though these plants had similar lignin levels, suggesting that lignin levels and growth defects can be uncoupled. While disrupting CADD only modestly increased S subunit levels in the cell wall, cadd C4H-F5H plants produced lignin highly enriched in S subunits. In addition, the mutants contained lignin primarily derived from hydroxycinnamaldehydes rather than the usual p-hydroxycinnamyl alcohols. The cadd C4H-F5H plants had sparse, incomplete secondary cell walls resembling loose assemblies of cellulose microfibrils (see figure) but lacked the collapsed xylem phenotype typically found in lignin-deficient mutants. Importantly, compared with wild-type, fah1, and C4H-F5H plants, cadd C4H-F5H plants, as well as cadc cadd and fah1 cadc cadd plants, exhibited increased cellulose-to-glucose conversion due to enhanced enzyme-catalyzed cell wall digestibility, which could be attributed to their high levels of aldehyde-rich lignin. Thus, lignin composition appears to be a more important determinant of cell wall digestibility than lignin content, a finding that may ultimately lead to more efficient production of cellulosic ethanol.

Transmission electron microscopy images of 2-month-old inflorescence tissue showing cell wall ultrastructure. Bars = 1 μm. (Reprinted from Anderson et al. [2015], Figure 8.)

References

- Anderson N.A., Tobimatsu Y., Ciesielski P.N., Ximenes E., Ralph J., Donohoe B.S., Ladisch M., Chapple C. (2015). Manipulation of guaiacyl and syringyl monomer biosynthesis in an Arabidopsis cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase mutant results in atypical lignin biosynthesis and modified cell wall structure. Plant Cell 27: 10.1105/tpc.15.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz N.D., Chapple C. (2013). Can genetic engineering of lignin deposition be accomplished without an unacceptable yield penalty? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24: 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon B.D., Barnes J.R., Halvorsen K.E. (2007). Grain and cellulosic ethanol: History, economics, and energy policy. Biomass Bioenergy 31: 416–425. [Google Scholar]