Abstract

Gingival enlargement is one of the frequent features of gingival diseases. However due to their varied presentations, the diagnosis of these entities becomes challenging for the clinician. They can be categorized based on their etiopathogenesis, location, size, extent, etc. Based on the existing knowledge and clinical experience, a differential diagnosis can be formulated. Subsequently, after detailed investigation, clinician makes a final diagnosis or diagnosis of exclusion. A perfect diagnosis is critically important, since the management of these lesions and prevention of their recurrence is completely dependent on it. Furthermore, in some cases where gingival enlargement could be the primary sign of potentially lethal systemic diseases, a correct diagnosis of these enlargements could prove life saving for the patient or at least initiate early treatment and improve the quality of life. The purpose of this review article is to highlight significant findings of different types of gingival enlargement which would help clinician to differentiate between them. A detailed decision tree is also designed for the practitioners, which will help them arrive at a diagnosis in a systematic manner. There still could be some lesions which may present in an unusual manner and make the diagnosis challenging. By knowing the existence of common and rare presentations of gingival enlargement, one can keep a broad view when formulating a differential diagnosis of localized (isolated, discrete, regional) or generalized gingival enlargement.

Keywords: Differential diagnosis, Gingival hyperplasia, Gingival overgrowth, Gingival diseases, Decision tree

Core tip: In clinical dentistry, patients frequently report with isolated/regional or generalized gingival enlargements, which could fall under varied presentations. The diagnosis of these lesions is essential for their successful management and of the patient as a whole. This article revises the existing knowledge of different types of enlargements and highlights some important diagnostic features. A customized decision tree is designed, which will help clinicians to keep a broad view when formulating a differential diagnosis of localized (isolated, discrete, regional) or generalized gingival enlargement and arrive at a particular diagnosis is an easy and systematic manner.

INTRODUCTION

Gingival enlargement or gingival overgrowth, a common trait of gingival disease, is characterized by an increase in the size of gingiva. Pertinent management depends on precisely diagnosing the origin of enlargement. However, the skills of a clinician is put to test when arriving at a particular diagnosis among the myriad of gingival enlargements that can be classified according to etiologic factors and pathologic changes, according to location and distribution and/or according to the degree of enlargement. Based on etiopathogenesis, enlargements could be inflammatory, drug influenced, those associated with systemic conditions or diseases, neoplastic or false enlargements. According to location, enlargements could be marginal, papillary or diffuse. Based on distribution they can be localized or generalized. Localized enlargements could be further divided into three sub-types, viz., “isolated, discrete” or “regional”. “Isolated” enlargements are those limited to gingiva adjacent to single or two teeth (e.g., gingival/periodontal abscess). “Discrete” lesions are isolated sessile or pedunculated, tumor-like enlargements (e.g., fibroma/pyogenic granuloma). “Regional” enlargements refer to involvement of gingiva around three or more teeth in one or multiple areas of the mouth (e.g., inflammatory enlargement associated with mouth breathing in maxillary and mandibular anterior region). “Generalized” enlargement refers to involvement of gingiva adjacent to almost all the teeth present (e.g., drug influenced gingival overgrowth). Inglés et al[1] summarized different methods and presented their clinical index to measure the degree of gingival enlargements.

The purpose of this article is to highlight significant findings of different types of gingival enlargement which would help clinician to differentiate between them. For the purpose of clinical diagnosis, enlargements mentioned in this review are grossly are divided into isolated lesions (epulis) and regional or generalized gingival enlargements. Among these, diagnostic points are discussed for the more commonly occurring lesions and the very rare and unusual presentation are listed as per the category to which they belong.

ISOLATED REACTIVE LESIONS OF THE GINGIVA

Localized enlargement of gingiva, historically termed as edulis[2], refers to any solitary/discrete, pedunculated or sessile swellings of the gingiva with no histologic characterization of a particular lesion. A corrective term “reactive lesion of the gingiva”[3], seems to be more appropriate for these category of swellings. Frequent diagnosis in this category is inflammatory rather than neoplastic and may fall in one of the following group of reactive lesions: fibrous epulis/peripheral fibroma, angiogranuloma/pyogenic granuloma and the peripheral giant cell lesion/granuloma.

Fibrous epulis/peripheral fibroma

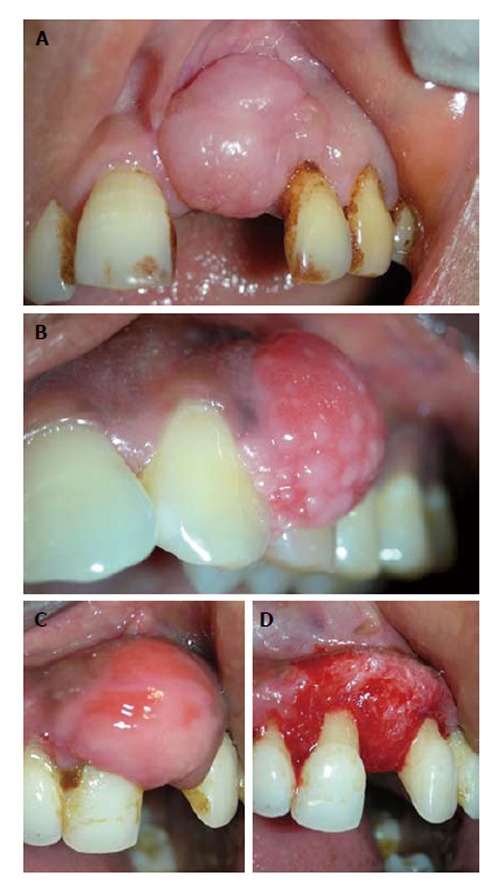

In adults, this lesion frequently represents as firm, pink, un-inflammed mass, and it seems to grow from below the free gingival margin/interdental papilla (Figure 1A). Most often the lesion is painless. Pain may be associated due to secondary traumata via brushing, flossing or chewing. Histologically, the fibroma may show additional focus of calcification (peripheral calcifying fibroma), foci of cementicles (peripheral cementifying fibroma, Figure 1B) or trabeculae of bone (peripheral ossifying fibroma, Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Fibrous epulis and its subtypes. A: Peripheral fibroma, presenting as pink firm, uninflammed mass growing from under the gingiva; B: Peripheral cementifying fibroma, a subcategory of fibroma, shows additional foci of cementicles; C and D: Surgical exposure of the lesion showing extensive bone formation in the core of the lesion. Also presence of bony trabeculae was seen histologically.

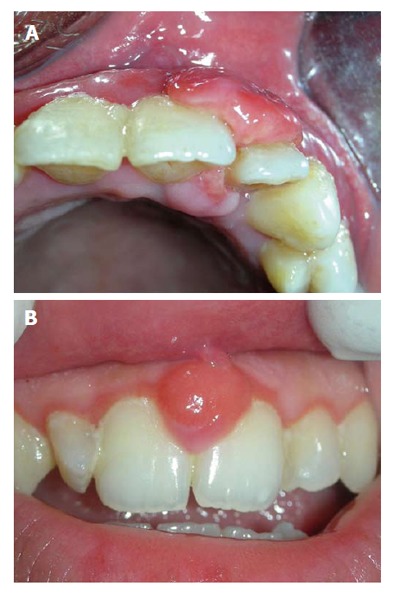

Angiogranuloma/pyogenic granuloma

Presents in adults as smooth surfaced mass, often ulcerated and grows from beneath the gingival margin. These reddish/bluish color mass are highly vascular, compressible and could bleed readily. Typically they grow rapidly within first few weeks and then slowly. The mass may penetrate interdentally and present as bilobular (buccal and lingual) mass connected through the col area, but bone erosion in uncommon (Figure 2A). Angiogranuloma which appears during pregnancy are termed as pregnancy epulis/tumor or granuloma gravidarum (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Angiogranulomas may present as: Pyogenic granuloma, a bilobular mass connected through the col area (A), and similar lesion occurring during pregnancy is termed as “pregnancy epulis” (B).

Histologically, the stratified squamous epithelium is thickened, with prominent rete pegs and some degree of intracellular and extracellular edema, prominent intercellular bridges and leukocytic infiltration.

Peripheral giant cell granuloma

They occur particularly in anterior region in young patients or in posterior mouth during mixed dentition phase and in adults. They are very aggressive lesions with significant growth potential. The high vascularity of these lesions can be understood by their purplish-red color and tendency to bleed. They also tend to penetrate interdentally and erosion of adjacent bone along with separation of adjacent teeth is a common occurrence (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Lesion of peripheral giant cell granuloma. This highly vascular lesion is characterized by purplish red-color and its tendency to bleed.

Gingival cysts

Gingival cysts are unusual cysts of odontogenic source. They are frequently found in females in their 50’s or 60’s. A greater number of these are found on the labial attached gingiva of the mandibular anterior teeth. Presence of fluid may give them a bluish hue and they may lead to resorption of the labial bone due to pressure. Radiographically, its radiolucency may sometimes lead to confusion with lateral periodontal cyst. Excisional biopsy is the best management for these lesions[4].

Neoplastic

The localized epulis like lesions can also be classified as being benign or malignant. Benign masses could be, fibroma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, central giant cell granuloma, papilloma, leukoplakia, nevus[5], myoblastoma[6], hemangioma (Figure 4A)[7,8] neurilemoma[9], neurofibroma[10], ameloblastoma[11]. Malignant tumors could be squamous cell carcinoma or melanoma. Among sarcomas, Kaposi’s sarcoma[12] is more common, and fibrosacroma, lymphosarcoma and reticulum cell sarcoma are rarely reported[13]. Other rare lesions (< 2% prevalence) include angioma, osteofibroma, myxoma, fibropapilloma, adenoma and lipoma[14].

Figure 4.

Other uncommon localized gingival enalargements which could be misdiagnosed as epulis. A: Hemangioma located in mandibular right quadrant; B: Mucocele associated with palatal minor salivary gland; C and D: A lateral periodontal cyst projecting labially and causing localized gingival enlargement.

Others

Some other localized chronic lesions that can be misdiagnosed as epulis would be palatal mucocele (Figure 4B), a lateral periodontal cyst projecting on labial/lingual surface (Figure 4C and D), etc.

Acute

The acute form of isolated gingival enlargement could be various abscesses such as gingival, periodontal, periapical or pericoronal. They can be differentiated from their location and vitality of the associated tooth. It could be located near gingival margin or papilla (gingival abscess) (Figure 5A), or may be diffuse and forms significant portion of attached gingiva (periodontal abscess) (Figure 5B). When the associated tooth is non-vital the lesion may be originated from an endodontic problem (periapical abscess/endo-perio lesion) (Figure 5C). Often the pericoronal flap covering distal most mandibular teeth might become inflamed and swollen. Abscess of these pericoronal flaps could eventually develop if the inflammation persists (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Abscess presenting as localized gingival enlargement. A: Gingival abscess, near gingival margin or papilla; B: In periodontal abscess, the swelling is diffuse; C: Periapical abscess, near apex of concerned tooth; D: Abscess of pericoronal flap.

Histopathological examination of gingival/periodontal/pericoronal abscess may present purulent focus in the connective tissue, surrounded by diffuse infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, edematous tissue and vascular engorgement. The surface epithelium has varying degrees of intra- and extracellular edema, invasion by leukocytes, and sometimes ulceration.

CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES OF GENERALIZED GINGIVAL ENLARGEMENT

More commonly, gingival disease manifests as regional or generalized gingival enlargement, which might fall into one of the different types.

Inflammatory gingival enlargement

These are inflammatory response to local irritant associated with gingiva. The irritant could be microbial deposits (plaque and calculus) (Figure 6A), fractured tooth, overhanging restorations, ill-fitting prosthesis (Figure 6B), orthodontic brackets (Figure 6C), etc. The presentation begins as slight ballooning of the papilla or marginal gingiva, depending upon the location of the irritant. The bulge may progressively increase in size and extent to become generalized. Clinical they may appear bluish or deep red. They are frequently friable and soft with a smooth shiny surface and they usually bleed easily. Occasionally, chronic inflammatory enlargement may also present as firm, resilient, pink and fibrotic enlargement which histologically show abundance of fibroblasts and collagen fibers.

Figure 6.

Inflammatory gingival enlargement. A: Plaque and calculus; B: Ill-fitting prosthesis; C: Orthodontic brackets.

Gingival enlargement in mouth breathers

Although considered as inflammatory, the exact mechanism of enlargement in mouth breathers is not clear. It is thought to be due to alternate wetting and drying of the gingival surface. The gingiva appears red and edematous with diffuse shiny surface. A diagnostic feature of this type of enlargement would be presence of significant enlargement in maxillary and mandibular anterior regions and no involvement of posteriors. In a typical bimaxillary protrusion case, the enlargement will be limited to palatal aspect of maxillary anteriors and labial aspect of mandibular anteriors. Patients present with mouth breathing habit that may be due to short upper lip, hyperactive labii superioris, proclined incisors, rhinitis, etc.

Fibrotic

Drug induced gingival enlargement: There are many anticonvulsants, immuno-suppressants and calcium channel blockers that may lead to gingival enlargement in varied presentations (Table 1 and Figure 7). Signs and symptoms related to gingival enlargement are seen within 2-4 mo of initiation of drug intake. Usually at the initial presentation there is no pain. The enlargement starts as beadlike enlargement of the interdental papilla and eventually may involve marginal gingiva. When not involved by secondary inflammation, the enlargement looks like mulberry shape, firm, pink and resilient with minute lobulations and no bleeding on probing. Although it may involve the gingiva around all teeth, it is more prominent in maxillary and mandibular anteriors. It will be absent in edentulous areas and will disappear in areas where teeth are extracted. When infected secondarily, there is increase in the size of existing enlargement and adds characteristic features of inflammatory enlargement. Among commonly encountered drug induced gingival enlargement (DIGO), those due to immunosuppressive agent like cyclosporine, appear more vascularized than phenytoin induced[17].

Table 1.

Different drugs known to predispose to gingival enlargements

Figure 7.

Drug influenced gingival overgrowth. A: Superimposed with secondary inflammation; B: Fibrotic and leathery.

When patients are in combination therapy, in which two or more drugs are known to cause gingival enlargement, then, which should be attributed to the diagnosis of DIGO, is a puzzle. One way to arrive at a diagnosis in such cases is to consult the patient’s physician, request him to substitute/stop one drug at a time, starting with the one that would have least effect on patient’s routine schedule. Frequently, patient gives history of related medications (antihypertensives/anticonvulsants/immune-suppressants) since many years but enlargement was noted since few months. In these cases, it becomes difficult to associate duration of occurrence of enlargement with related drug history. Specific query related to recent change in type/dose of drug will help to associate both.

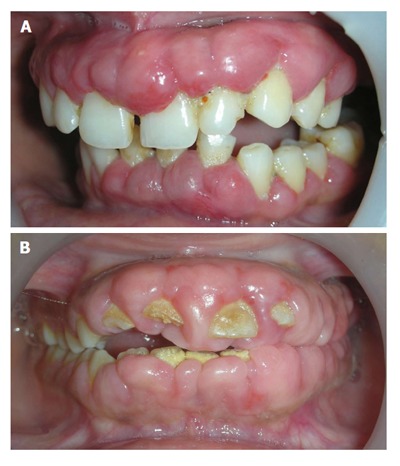

Genetic disorders associated with gingival enlargement: They can be divided into 4 primary categories based on their etiology, clinical features and histology. Namely, idiopathic gingival enlargement, lysosomal storage disorders, vascular disorders and those associated with characteristic dental abnormalities (Table 2). Idiopathic gingival enlargement is also referred to as congenital familial fibromatosis, gingivomatosis, idiopathic fibromatosis, elephantiasis and hereditary gingival hyperplasia. It presents as unusual fibrotic gingival enlargement of localized or generalized extent. It may present as a specific entity or as a part of syndrome. Diagnosis can be made by a positive family history of gingival enlargement. It usually begins with the eruption of the primary or permanent dentition. A frequent finding could be presence of firm bulky enlargement of gingiva restricted to maxillary and mandibular second and third molar areas only. The enlarged mass may be pink or reddish and may be firm/nodular on palpation. Alveolar bone is rarely affected, but presence of pseudo-pockets and difficulty in maintaining oral hygiene may lead to some periodontal problems. Extensive overgrowths can lead to esthetic and functional concerns to the patient (Figure 8).

Table 2.

Gingival enlargement associated with syndromes in different types of genetic disorders

| Syndromes associated with heriditary gingival fibromatosis | |

| Zimmerman-Laband syndrome[18] | Abnormal fingers, nails, nose and ears, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, hyperextensible metacarpophalangeal joints |

| Ramon syndrome[19] | Cherubism, seizures, mental deficiency, hypertrichosis, stunted growth, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis |

| Systemic Hyalinosis[20] | Painful joint contractures, diffuse thickening of the skin with pearly papules and fleshy nodules and failure to thrive |

| Jones syndrome[21] | Progressive sensorineural deafness |

| Rutherford syndrome[22] | Corneal opacity, mental retardation and aggressive behavior, failure of tooth eruption |

| Cross syndrome[23] | Hypopigmentation, mental retardation and writhing movement of hand and legs |

| Schinzel-Giedion syndrome[24] | Severe mid face retraction, severe mental retardation and congenital heart defect, patient usually die under 10 yr of age |

| Costello syndrome[25] | Macrostomia, redundant skin of neck, hands and feet, nasal and perioral papillomas, enlargement within first years of life |

| Syndromes associated with lysosomal storage diseases | |

| Hurler syndrome[26] | Dwarfism, flexion contractures, hernias, corneal clouding, macroglossia, short mandibular rami, peg-shaped teeth |

| Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome[27] | Enlargement of skull, corneal opacities, short peg-shaped poorly formed teeth, hypertrophy of alveolar ridges, anterior open bite |

| Neimann-Pick disease[28] | Thick lips, macroglossia and widely spaced teeth |

| Anderson-Fabry disease[29,30] | Painful crises on extremities and abdomen, angiokeratomas of skin, labial mucosa and buccal mucosa |

| Cowden syndrome[31] | Cobblestone papules of gingiva and buccal mucosa, macrocephaly, multiple hamartomas, learning disabilities, autism |

| Gingival enlargement associated with vascular disorders | |

| Sturge-Weber syndrome[32] | Unilateral cutaneous nevi, unilateral vascular hyperplasia, neurological manifestations and ocular complications |

| Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome[33] | Capillary hemangiomas, increased size of lips, tongue, teeth malformations, delayed exfoliation of teeth, calcified roots |

| Gingival enlargement associated with characteristic dental abnormalities | |

| Wilson syndrome[34] | Enamel hypoplasia, multiple small red papules of lips, early onset periodontitis and repeated oral candidiasis, signs of cirrhosis |

| GoltzGorlin syndrome[35] | Partial anodontia, hypoplastic teeth, atrophy and linear pigmentation of skin, herniation of fat, multiple papillomas, digital anomalies |

Figure 8.

Unusual firm fibrotic gingival enlargements in a patient with hereditary gingival fibromatosis.

Conditioned gingival enlargement

Hormonal: Generalized gingival hyperplasia, during pregnancy and puberty, is influenced by hormonal changes that pretentious the response to local irritants. The interproximal gingiva shows more prominent enlargement than the facial and/or lingual surfaces (Figure 9). The enlarged gingiva usually is soft and friable, bright red or magenta, with a smooth, shiny surface. Bleeding may occur extemporaneously or on mild stimulation. The enlargement may reduce spontaneously after the delivery, but complete elimination may require the removal of all local irritants and additional surgical intervention of any fibrotic remnants.

Figure 9.

Typical multiple interproximal enlargements in a pregnant patient.

Vitamin C deficiency: Deficiency of vitamin C is defined as a serum ascorbic acid level < 2 μg/mL. Diabetes, stress and smoking are the commonly labeled factors leading to mild vitamin C deficiency. The gingiva, of vitamin C deficiency associated enlargement, is bluish red, soft and friable with a smooth, shiny surface. Bleeding may occur spontaneously or on slight irritation. Surface necrosis with pseudomembrane formation are also frequently seen[36]. Kubota et al[37] pointed out that high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels were inversely proportionate with serum vitamin C concentration, and therefore, hs-CRP blood level may be elevated in these patients.

Plasma cell gingivitis: The etiology of this entity is difficult to establish, but it is considered to be a hypersensitivity reaction with affluent plasma cells seen histologically. Usual allergens known to be associated with this lesion could be, e.g., toothpaste, khat, food product particularly cinnamon, chewing gum or unknown origin. It might bleed on provocation. Patients usually complain about burning sensation on eating hot and spicy food. Appearance is reddish in color, involves almost complete attached gingiva, slight granular surface appearance is typical (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Appearance of gingiva in patient with plasma cell gingival enlargement. The color is reddish and involves almost complete attached gingiva and slightly granular appearance.

Gingival enlargement associated with systemic disease

Leukemia: Generalized gingival enlargement associated with leukemia is due to the massive infiltration of leukemic cells in the gingival connective tissue. Clinically it may mimic inflammatory origin. Apart from gingival enlargement other associated features could be oral ulceration, spontaneous gingival bleeding, petechiae, mucosal pallor, herpetic infections and candidiasis. Rarely, uncommon features such numbness in chin and/or tooth pain has been reported[38]. The most serious condition associated with gingival enlargement in this category would be acute myeloid leukemia. It can be associated with signs and symptoms of bone marrow failure, such as ecchymoses, night sweats, recent infections and lethargy. An expeditious diagnosis can be made by a simple full blood count. A rare case of gingival hyperplasia secondary to acute lymphoblastic leukemia has also been reported[39].

Wegener’s Granulomatosis: “Strawberry gingivitis”, formed by reddish-purple exophytic gingival swelling with patechial haemorrhages, is a characteristic sign of Wegener’s granulomatosis. The oral lesions could be of great help in timely diagnosis of this potentially fatal condition, because they persists for a long time before multi-organ involvement occurs (Figure 11)[40,41]. At least two of the following conditions should be fulfilled to diagnose the condition as Wegener’s granulomatosis: (1) ulcerative lesions of oral mucosa or nasal bleeding or inflammation; (2) nodules, fixed infiltrates or cavities in chest radiograph; (3) abnormal urinary sediment; and (4) granulomatous inflammation on biopsy[40].

Figure 11.

Gingival condition in patient with Wegenersgranulomatosis, presents as reddish purple, exophytic gingival overgrowth.

Crohn’s disease: The gingiva is pink, firm and almost leathery in consistency, with a characteristic minutely pebbled surface. Signs and symptoms of these conditions must be strenuously trailed in these patients. It is normally associated with swelling of lips, bowel disorders, fever and ulcers. A consultation with gastro-enterologist will prove to be helpful.

Sarcoidosis: Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disorder. The most common presentation consists of pulmonary infiltration and hilar lymphadenopathy, dermal and ocular lesions[42], however oral involvement is uncommon. There are no specific tests for sarcoidosis. Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is mainly based on exclusion of other non-caseating granulomas forming conditions and other laboratory tests[42,43]. Eosinophil count might be significantly increased (normal range 0%-4%), and serum angiotensin converting enzyme levels can also be significantly raised (normal range less than 670 nkat/L). Chest X-ray might show hilar lymphadenopathy[44].

Tuberculous gingival enlargement: Primary oral tuberculous lesions are very rare, but when they occur they are usually seen in younger age. The lesions themselves remain painless in most cases, however associated caseation of the dependent lymph nodes may be seen[45,46]. Furthermore, primary tuberculosis manifesting solely as gingival enlargement is extremely rare which can be diagnosed based on history of fever, weakness, loss of appetite and weight loss[47]. The diagnosis can be confirmed based on histopathology, complete blood count and polymerase chain reaction[47]. In contrast, secondary oral tuberculosis can be seen in 0.05% to 1.5% of cases and the prevalence is more in older adults[48,49].

Unusual presentations: Generalized gingival enlargement has been rarely reported with amelogenesis imperfecta[50], Hashimoto’s thyroiditis[51], I-cell disease[52] and Multiple myeloma[53].

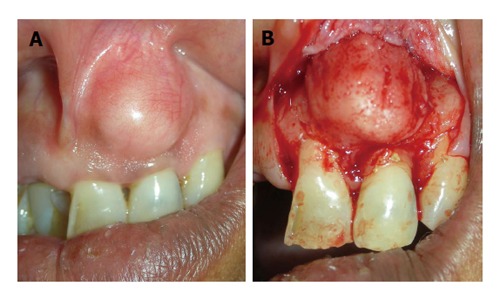

False enlargement: These pseudo-enlargements appears as a result of increase in size of underlying osseous (tori, exostosis, Paget’s disease, cherubism, osteoma, etc.) or dental tissues (during tooth eruption). The overlying gingiva presents with no abnormal clinical features except the massive increase in size of the area (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Case of false enlargement wherein. A: The overlying gingiva presents with no abnormal clinical features except the massive increase in size of the area; B: Formed completely by underlying bone.

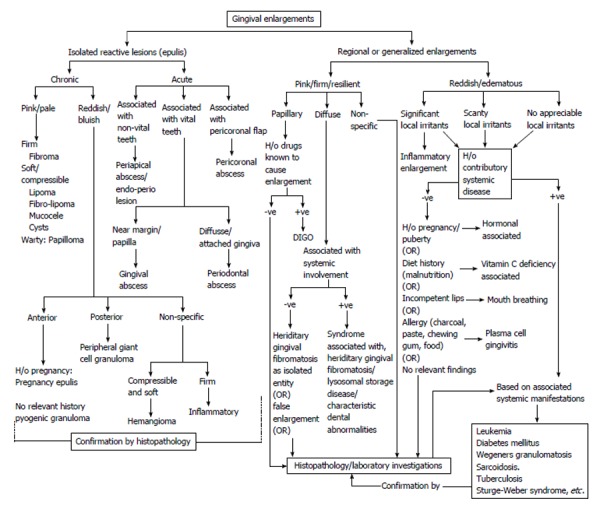

Decision tree: Differential diagnosis of gingival enlargement requires thorough dental and medical history, careful evaluation of the type, nature and extent of enlargement and identification of etiologic or predisposing factors. A decision tree (Figure 13) is specially designed to get a broad overview of different possible diagnosis for localized or generalized gingival enlargements. This systematic presentation would be very helpful for the clinicians to arrive at a particular diagnosis. Furthermore, laboratory investigations and/or biopsy specimens may be required to confirm the diagnosis or make a diagnosis of exclusion.

Figure 13.

Decision tree for differential diagnosis of isolated, regional and generalized gingival enlargement. DIGO: Drug induced gingival enlargement.

CONCLUSION

Inspite of a myriad of etiology, gingival enlargements can often be diagnosed by a careful history (e.g., drug influenced or hormonal influenced gingival enlargement), by location (e.g., mouth-breathing enlargement around anterior teeth) or by the clinical presentation (e.g., strawberry gingivitis). Presence of local irritants (plaque and calculus) could be primary or associated cause of gingival enlargements. Hence, plaque control is an essential aspect of management in all the patients. An excisional/incisional biopsy and/or hematologic/histologic examination may be needed occasionally to correctly diagnose the uncommon cases of gingival enlargement. The clinician should have an open mind and consider all possibilities before coming to the final diagnosis of the condition at hand.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Cho SY, Kai K, Vij M S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Conflict-of-interest statement: None.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: February 2, 2015

First decision: May 13, 2015

Article in press: August 3, 2015

References

- 1.Inglés E, Rossmann JA, Caffesse RG. New clinical index for drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Quintessence Int. 1999;30:467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee KW. The fibrous epulis and related lesions. Granuloma pyogenicum, ‘Pregnancy tumour’, fibro-epithelial polyp and calcifying fibroblastic granuloma. A clinico-pathological study. Periodontics. 1968;6:277–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kfir Y, Buchner A, Hansen LS. Reactive lesions of the gingiva. A clinicopathological study of 741 cases. J Periodontol. 1980;51:655–661. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.11.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giunta JL. Gingival cysts in the adult. J Periodontol. 2002;73:827–831. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.7.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen RR, Bruce KW. Nevus of the gingiva; report of case. J Oral Surg (Chic) 1954;12:254–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagen JO, Soule EH, Gores RJ. Granular-cell myoblastoma of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1961;14:454–466. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(61)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sznajder N, Dominguez FV, Carraro JJ, Lis G. Hemorrhagic hemangioma of gingiva: report of a case. J Periodontol. 1973;44:579–582. doi: 10.1902/jop.1973.44.9.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rashmi MS, Alka KD, Seema C. Oral hobnail hemangioma--a case report. Quintessence Int. 2008;39:507–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler CB. Benign and malignant neoplasms of the periodontium. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:33–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollack RP. Neurofibroma of the palatal mucosa. A case report. J Periodontol. 1990;61:456–458. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.7.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevenson AR, Austin BW. A case of ameloblastoma presenting as an exophytic gingival lesion. J Periodontol. 1990;61:378–381. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.6.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lager I, Altini M, Coleman H, Ali H. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study from South Africa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:701–710. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponnam SR, Srivastava G, Jampani N, Kamath VV. A fatal case of rapid gingival enlargement: Case report with brief review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:121–126. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.131938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernick S. Growths of the gingiva and palate; connective tissue tumors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1948;1:1098–1108. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(48)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallmon WW, Rossmann JA. The role of drugs in the pathogenesis of gingival overgrowth. A collective review of current concepts. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:176–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors . Dermatology. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seymour RA, Smith DG, Rogers SR. The comparative effects of azathioprine and cyclosporin on some gingival health parameters of renal transplant patients. A longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:610–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoogendijk CF, Marx J, Honey EM, Pretorius E, Christianson AL. Ultrastructural investigation of Zimmermann-Laband syndrome. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:423–426. doi: 10.1080/01913120601042245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suhanya J, Aggarwal C, Mohideen K, Jayachandran S, Ponniah I. Cherubism combined with epilepsy, mental retardation and gingival fibromatosis (Ramon syndrome): a case report. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:126–131. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0155-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Kamah GY, Fong K, El-Ruby M, Afifi HH, Clements SE, Lai-Cheong JE, Amr K, El-Darouti M, McGrath JA. Spectrum of mutations in the ANTXR2 (CMG2) gene in infantile systemic hyalinosis and juvenile hyaline fibromatosis. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:213–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasaboğlu O, Tümer C, Balci S. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis and sensorineural hearing loss in a 42-year-old man with Jones syndrome. Genet Couns. 2004;15:213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raja TA, Albadri S, Hood C. Case report: Rutherfurd syndrome associated with Marfan syndrome. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9:138–141. doi: 10.1007/BF03262625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witkop CJ. Heterogeneity in gingival fibromatosis. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1971;7:210–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondoh T, Kamimura N, Tsuru A, Matsumoto T, Matsuzaka T, Moriuchi H. A case of Schinzel-Giedion syndrome complicated with progressive severe gingival hyperplasia and progressive brain atrophy. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:181–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2001.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Digilio MC, Sarkozy A, Capolino R, Chiarini Testa MB, Esposito G, de Zorzi A, Cutrera R, Marino B, Dallapiccola B. Costello syndrome: clinical diagnosis in the first year of life. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:621–628. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas S, Tandon S. Hurler syndrome: a case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2000;24:335–338. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.24.4.ku653u75nv5vt735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guimarães Mdo C, de Farias SM, Costa AM, de Amorim RF. Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome: orofacial features after treatment by bone marrow transplant. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaisare S. Gingival enlargement in Niemann-Pick disease: a coincidence or link? Report of a unique case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:e35–e39. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young WG, Sauk JJ, Pihlstrom B, Fish AJ. Histopathology and electron and immunofluorescence microscopy of gingivitis granulomatosa associated with glossitis and cheilitis in a case of Anderson-Fabry disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;46:540–554. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young WG, Pihlstrom BL, Sauk JJ. Granulomatous gingivitis in Anderson-Fabry disease. J Periodontol. 1980;51:95–101. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan MH, Mester J, Peterson C, Yang Y, Chen JL, Rybicki LA, Milas K, Pederson H, Remzi B, Orloff MS, et al. A clinical scoring system for selection of patients for PTEN mutation testing is proposed on the basis of a prospective study of 3042 probands. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhansali RS, Yeltiwar RK, Agrawal AA. Periodontal management of gingival enlargement associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Periodontol. 2008;79:549–555. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.060478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira de Godoy JM, Fett-Conte AC. Dominant inheritance and intra-familial variations in the association of Sturge-Weber and Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndromes. Indian J Hum Genet. 2010;16:26–27. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.64943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tovaru S, Parlatescu I, Dumitriu AS, Bucur A, Kaplan I. Oral complications associated with D-penicillamine treatment for Wilson disease: a clinicopathologic report. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1231–1236. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maas SM, Lombardi MP, van Essen AJ, Wakeling EL, Castle B, Temple IK, Kumar VK, Writzl K, Hennekam RC. Phenotype and genotype in 17 patients with Goltz-Gorlin syndrome. J Med Genet. 2009;46:716–720. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.068403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omori K, Hanayama Y, Naruishi K, Akiyama K, Maeda H, Otsuka F, Takashiba S. Gingival overgrowth caused by vitamin C deficiency associated with metabolic syndrome and severe periodontal infection: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2014;2:286–295. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubota Y, Moriyama Y, Yamagishi K, Tanigawa T, Noda H, Yokota K, Harada M, Inagawa M, Oshima M, Sato S, et al. Serum vitamin C concentration and hs-CRP level in middle-aged Japanese men and women. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cetiner S, Alpaslan C, Gungor N and Kocak U. Tooth pain and numb chin as the initial presentation of systemic malignancy. Turk J Med Sci. 1999;29:719–722. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patil S, Kalla N, Ramesh DNSV, Kalla AR. Leukemic gingival enlargement: a report of two cases. Arch OrofacSci. 2010;5:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart C, Cohen D, Bhattacharyya I, Scheitler L, Riley S, Calamia K, Migliorati C, Baughman R, Langford P, Katz J. Oral manifestations of Wegener’s granulomatosis: a report of three cases and a literature review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:338–348; quiz 396, 398. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiboski CH, Regezi JA, Sanchez HC, Silverman S. Oral lesions as the first clinical sign of microscopic polyangiitis: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:707–711. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.129178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samtsov AV. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:385–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1224–1234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704243361706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kadiwala SA, Dixit MB. Gingival enlargement unveiling sarcoidosis: Report of a rare case. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:551–555. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.123087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nwoku LA, Kekere-Ekun TA, Sawyer DR, Olude OO. Primary tuberculous osteomyelitis of the mandible. J Maxillofac Surg. 1983;11:46–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(83)80011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith WH, Davies D, Mason KD, Onions JP. Intraoral and pulmonary tuberculosis following dental treatment. Lancet. 1982;1:842–844. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91886-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karthikeyan BV, Pradeep AR, Sharma CG. Primary tuberculous gingival enlargement: a rare entity. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72:645–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weaver RA. Tuberculosis of the tongue. JAMA. 1976;235:2418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woolfe M. Secondary tuberculous ulceration of the tongue. A case report. Br Dent J. 1968;125:270–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Connell S, Davies J, Smallridge J, Vaidyanathan M. Amelogenesis imperfecta associated with dental follicular-like hamartomas and generalised gingival enlargement. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;15:361–368. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fisekcioglu E, Dolekoglu S, Ilguy D. Idiopathic gingival hyperplasia: clinical features and differential diagnosis. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee W, O’Donnell D. Severe gingival hyperplasia in a child with I-cell disease. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:41–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jain S, Kaur H, Kansal G, Gupta P. Multiple myeloma presenting as gingival hyperplasia. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:391–393. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.115652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]