Abstract

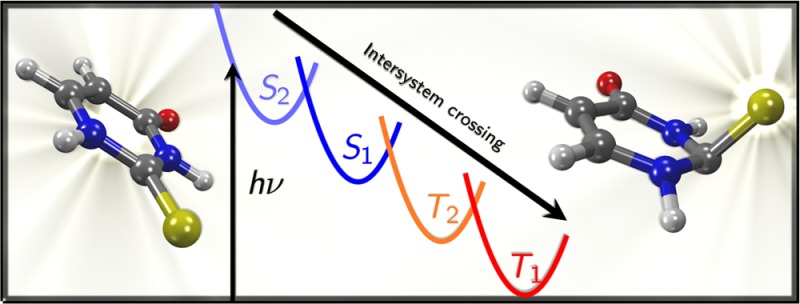

Accurate excited-state quantum chemical calculations on 2-thiouracil, employing large active spaces and up to quadruple-ζ quality basis sets in multistate complete active space perturbation theory calculations, are reported. The results suggest that the main relaxation path for 2-thiouracil after photoexcitation should be S2 → S1 → T2 → T1, and that this relaxation occurs on a subpicosecond time scale. There are two deactivation pathways from the initially excited bright S2 state to S1, one of which is nearly barrierless and should promote ultrafast internal conversion. After relaxation to the S1 minimum, small singlet–triplet energy gaps and spin–orbit couplings of about 130 cm–1 are expected to facilitate intersystem crossing to T2, from where very fast internal conversion to T1 occurs. An important finding is that 2-thiouracil shows strong pyramidalization at the carbon atom of the thiocarbonyl group in several excited states.

Introduction

Nucleobase analogues, which are structurally similar to the canonical nucleobases adenine, guanine, cytosine, uracil, and thymine, play an important role in biochemistry. Many nucleobase analogues are actively used as drugs for chemotherapy1 and various other diseases or as fluorescence markers2−4 in biomolecular research. Oftentimes, the close structural relation to the parent nucleobases is responsible for the usefulness of a given nucleobase analogue. For example, many nucleobase analogues can substitute the canonical nucleobases in DNA and thus affect the properties of DNA. Despite this structural similarity, the photochemical properties of nucleobase analogues can drastically differ from the ones of their parent nucleobases. The canonical nucleobases are known to exhibit ultrafast relaxation to the ground state after irradiation with UV light, which gives DNA a high stability against UV-induced damage.5−7 In contrast, for a large number of nucleobase analogues,8−11 slow internal conversion to the ground state, luminescence, and intersystem crossing is reported. This difference is correlated with the fact that the excited-state potential energy surfaces (PES) are sensitive to the functionalization of the molecule and even small changes in the relative energies of the PES can lead to drastically different excited-state dynamics. For this reason, the incorporation of nucleobase analogues into DNA can severely affect its photostability.

Thiated nucleobases (thiobases), where one or more oxygen atoms of a canonical nucleobase are exchanged for sulfur, are a very good example of the above-described behavior. Thiobases are found in several types of RNA12 but also have been employed as drugs. For example, 6-thioguanine (6TG) is a very important cancer and anti-inflammatory drug, listed as an essential medicine by the WHO.13 Interestingly, a side effect of 6TG treatment is an 100-fold increase in the incidence of skin cancer,14 which has been attributed to its very different photochemistry15−19 in comparison with guanine. Similarly, 2-thiouracil (2TU) has been historically used as an antithyroid drug (6-n-propyl-2-thiouracil20 is currently listed as essential by the WHO13) and has shown some potential for the development of cytostatika,21 heavy-metal antidotes,22 or photosensitizers for photodynamical therapy.23 As with 6TG, the different photophysics and photochemistry of 2TU in comparison with uracil could lead to significant side effects in potential medical applications of 2TU. This relevance has led to an increased interest in the photophysics of thiobases.

The UV absorption spectrum and excited states of 2TU have been studied in detail. The first band of the UV absorption spectrum has a maximum at approximately 270 nm, with the band extending to about 350 nm.24,25 Additionally, this band shows either a shoulder or a second maximum at around 290 nm, depending on solvent.24,26−28 Hence, a large portion of the absorption band lies in the UV–B range. An nπ* state has been observed in the circular dichroism (CD) spectra of 2-thiouridine29 and 2-thiothymidine30 at about 320 nm, but analogous CD spectra for the nonchiral 2TU cannot be measured. Time-resolved spectroscopy of 2TU was reported in the microsecond regime27 and the femtosecond regime.28 For both 2TU and the closely related 2-thiothymine (2TT),28,30−32 all studies report a near-unity quantum yield for intersystem crossing (ISC) and significant phosphorescence. ISC leads to the formation of long-lived and often very reactive triplet states and is therefore responsible for the loss of photostability. Moreover, in the presence of oxygen, reactive oxygen species (e.g., singlet oxygen) can be generated, ultimately leading to DNA damage in a biological environment.

Despite the solid evidence of the high ISC rate of 2TU, the detailed mechanism leading to the population of the harmful triplet states is still not yet understood. Pollum and Crespo-Hernández28 reported ultrafast (subpicosecond resolution) transient absorption spectra of 2TU and found that the first step after excitation to the S2 (ππ*) state, which is mainly responsible for the first absorption band, is an ultrafast (<200 fs) internal conversion to the S1 (nπ*) state, from where ISC occurs with a time constant of 300–400 fs.

From a theoretical point of view, the topology of the excited-state PES of 2TU was investigated in two recent studies. Cui and Fang33 reported a large quantity of excited-state minima and crossings, using the multiconfigurational CASPT2//CASSCF methodology (complete active space perturbation theory//complete active space self-consistent field) and imposing planarity (Cs symmetry) in almost all optimizations. They characterized three (reportedly competing) pathways: S2 → S1 → T1, S2 → T2 → T1, and S2 → T3 → T2 → T1. However, because it can be expected that most stationary points on the excited-state PES exhibit some degree of out-of-plane distortions, the ISC mechanisms reported by these authors are not reliable. Indeed, Gobbo and Borin34 (also using CASPT2//CASSCF) found several nonplanar geometries, among them a ππ* minimum and a conical intersection between ππ* and S0. Even though the structural details were different than in the previous study,33 the latter authors also reported two similar mechanisms, S2 → S1 → T1 and S2 → T2 → T1, as the most likely reaction pathways.

Although ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy28 suggests S2 → S1 → T1 as the most probable pathway, it seems that a complete understanding of the photophysics of 2TU has not been reached yet. A clear identification of the relaxation pathway from theoretical calculations should be obtained by means of dynamical simulations, for example, using the surface hopping nonadiabatic method Sharc(35,36) developed in our group, which allows for a simultaneous description of internal conversion and ISC. As a reference for future excited-state dynamics simulations, in this paper we report a thorough account of all relevant excited-state minima and crossings of 2TU calculated at the highest affordable level of theory, i.e., including electronic correlation by means of CASPT2, not only in the energy calculations but also in the determination of the geometries. This study therefore extends and complements the existing studies of Cui and Fang33 and Gobbo and Borin,34 providing the most accurate energies and geometries reported so far. Moreover, the paths connecting the optimized structures were investigated using large-active-space and large-basis-set calculations to assess the viability of smaller active spaces and smaller basis sets for CASPT2-based excited-state dynamics, which will be reported in an upcoming publication.

Theoretical Methods

Level of Theory

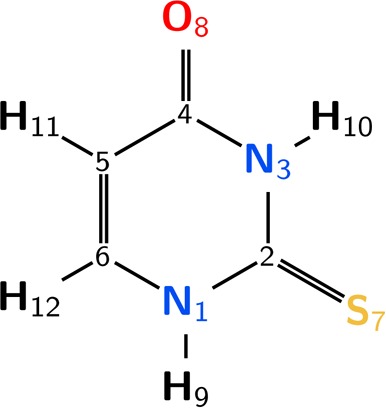

Experimental and theoretical studies confirm that 2TU exists in the gas phase and solution only in one tautomeric form, with a thione and a keto group and the prototropic hydrogens attached to the nitrogen atoms.37−40 Hence, in this study we focus exclusively on this tautomer, whose structure and the numbering of all atoms are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of the most stable tautomer of 2TU and atom numbering.

To find all structures that might be relevant for the excited-state dynamics of 2TU, geometries were optimized at several levels of theory. First, SA(4 + 3)-CASSCF(14,10)/def2-svp (averaging over 4 singlet and 3 triplet states in a single CASSCF41 calculation) was employed, using the Molpro 2012 suite.42,43 Second, using Columbus 7,44,45 we employed MRCIS/cc-pVDZ (multireference configuration interaction including single excitations) with a CAS(6,5) reference space based on SA(4 + 2)-CASSCF(12,9) orbitals. Both methods were used to optimize minima and crossing points between states of the same and of different multiplicity. Third, the minima were additionally optimized using MS(3/3)-CASPT2/cc-pVDZ (multistate CASPT246,47 including 3 singlets or 3 triplets) based on SA(4/3)-CASSCF(12,9) orbitals (state-averaging over 4 singlets or 3 triplets in separate CASSCF calculations). These “MS-CASPT2(12,9)” calculations were performed with Molcas 8.0,48,49 the IPEA shift50 was set to zero and no level shifts were employed. At all levels of theory, the Douglas–Kroll–Hess (DKH) scalar-relativistic Hamiltonian51 was employed. The composition of the various active and reference spaces is described in the next subsection.

Single-point energies were calculated at the same MRCIS and MS-CASPT2 levels of theory as used for optimizations. Additionally, single-point calculations (at geometries optimized with MS-CASPT2(12,9)) were performed using SA(6/4)-CASPT2, with the default IPEA shift, no level shifts, and the DKH Hamiltonian (the complete procedure is abbreviated as “MS-CASPT2(16,12)” in the following). For these calculations, the atomic Cholesky decomposition53 method was employed to speed up the calculations. The energies from the MS-CASPT2(16,12) calculations serve as reference for the computationally much more efficient MRCIS/cc-pVDZ and MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pVDZ computations.

State dipole moments were calculated with single-state CASPT2(16,12)/ano-rcc-vqzp, because they are not available at MS-CASPT2 level of theory.

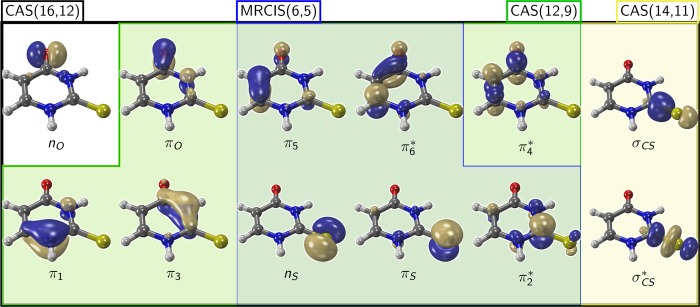

Orbitals

Figure 2 shows the orbitals of the largest active space employed in the CAS(16,12) calculations, together with the composition of the reduced active and reference spaces used in this work. In the largest case, the active space contains all the π and π* orbitals, the nO and nS lone pairs and the σCS, σCS* pair. The indices used in the orbital labels refer to the atom(s) where the orbital is (are) mostly localized. The figure is organized such that in the upper row all orbitals corresponding to the acrolein moiety (plus the σCS) are listed, whereas the lower row collects the orbitals localized on the thiourea moiety.

Figure 2.

Molecular orbitals in the various orbital spaces. The numerical indices of the orbitals refer to the atom where the largest part of the orbital is localized. Except for the σ orbitals on the right, the upper row depicts the acrolein-like orbitals, whereas the lower row depicts the thiourea-like orbitals.

At some geometries, it was not possible to obtain a correct CAS(16,12) active space and thus the active space was reduced to CAS(14,11) by excluding the nO orbital. The reason for this exclusion is that at the affected geometries, the nOπ* state is very high in energy and therefore would necessitate a larger number of states in the state-averaging procedure. However, because such a strategy would deteriorate the description of the more relevant lower states, the nO orbital was eliminated from the active space.

The σCS, σCS* pair is not relevant for the description of planar and almost planar geometries, but in the case of C2 pyramidalization these orbitals mix with the π orbitals and hence should be included in the active space. Yet, and as shown later, a CAS(12,9) active space without the σCS, σCS pair leads to a qualitatively correct description of the PESs.

For the MRCIS level of theory, mainly used for the preliminary optimization of crossing points, a reference space CAS(12,9) is still too large and hence was reduced to CAS(6,5), including the π5, πS, nS, π2* and π6 orbitals.

Results and Discussion

Vertical Excitation

Table 1 presents the excited-state energies calculated at the MS-CASPT2-optimized ground-state geometry. In the following, all numbers mentioned in the discussion are from the most accurate MS-CASPT2(16,12)/ano-rcc-vqzp calculations, unless noted otherwise. CASSCF and SS-CASPT2 results are available in the Supporting Information in Table S1.

Table 1. Vertical Excitation Energies of 2TU in eV (Oscillator Strength in Parentheses), Computed at the MS-CASPT2(12,9)-Optimized Geometry (MRCIS at MRCIS-Optimized Geometry).

| this work |

literature |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| state | PT2(16,12)a | PT2(12,9)b | MRCIS(6,5)c | Gobbo34,d | Cui33,e | exp25,28−30 |

| 1nSπ2* | 3.77 (0.00) | 3.70 (0.00) | 3.85 (0.00) | 3.65 (0.00) | 3.83 | 3.8 |

| 1πSπ6* | 4.25 (0.35) | 4.30 (0.11) | 5.78 (0.11) | 4.09 (0.24) | 4.3 | |

| 1nOπ6* | 4.65 (0.00) | 4.59 (0.00) | 4.76 | |||

| 1πSπ2* | 4.72 (0.15) | 5.11 (0.39) | 4.45 (0.45) | 4.46 | 4.6 | |

| 1nSπ6* | 5.16 (0.00) | 4.89 (0.00) | 5.62 (0.00) | 4.87 (0.00) | ||

| 3πSπ2* | 3.51 | 3.24 | 3.62 | 3.14 | ||

| 3nSπ2* | 3.88 | 3.76 | 3.76 | 3.60 | ||

| 3π5π6* | 4.11 | 3.83 | 4.44 | 3.67 | ||

| 3nOπ6* | 4.85 | 5.62 | 4.57 | |||

SA(6/4)-CASSCF(16,12) + MS(6/4)-CASPT2/ano-rcc-vqzp, IPEA = 0.25 au.

SA(4/3)-CASSCF(12,9) + MS(3/3)-CASPT2/cc-pVDZ, IPEA = 0.0 au.

SA(4+2)-CASSCF(12,9) + MRCIS(6,5)/cc-pVDZ.

SA(6/6)-CASSCF(14,10) + SS-CASPT2/ano-L-vdzp, IPEA = 0.0 au.

SA(4+3)-CASSCF(16,11) + CASPT2/cc-pvdz, IPEA = 0.0 au.

The ground state of 2TU has a closed-shell configuration. Its calculated dipole moment is 4.29 D (SS-CASPT2), which compares very well with the experimental value of 4.21 D.54

The lowest excited singlet state (S1) of 2TU is the 1nSπ2* state, where π2 is the antibonding π* orbital located mostly on the C2 atom. Hence, S1 describes an excitation that is local to the thiourea moiety of the molecule; the dipole moment of this state is very similar to the ground-state dipole moment (4.29 D at SS-CASPT2). The calculated vertical excitation energy is 3.77 eV (the lower-level calculations in Table 1 agree to within 0.1 eV). With an oscillator strength of approximately zero, this state does not contribute to the UV absorption spectrum. However, in the CD spectra of 2-thiouridine29 and 2-thiothymidine30 the nSπ* state appears at 3.8 eV, which fits very well with the calculated energy.

The S2 has 1πSπ6* character and describes an excitation from the πS orbital, localized on the sulfur atom, to the π6 orbital, which is mostly localized on C6. As already noted in the literature,34 this is a charge-transfer state and hence it possesses a large dipole moment, 5.15 D (SS-CASPT2). The energy of the state, 4.25 eV, is in line with the experimental value of 4.3 eV. The calculated oscillator strength is 0.35 and therefore, this state (together with 1πSπ2*, see below) dominates the low-energy side of the first band of the UV absorption spectrum.

The third excited state (S3) has 1nOπ6* character; i.e., it corresponds to an excitation from the oxygen lone pair to the π* orbital mostly localized on C6. Unlike S1 and S2, this state cannot be described by the more economic MS-CASPT2(12,9) and MRCIS calculations because they both exclude the nO orbital from the active/reference spaces. The energy of this state is 4.65 eV, comparable to the values of Gobbo and Borin34 and of Cui and Fang.33 Because the oscillator strength of this state is close to zero, it should not contribute to the absorption spectrum. No experimental data of this state are available. This state shows a comparably small dipole moment of 2.66 D.

The fourth excited state (S4) has 1πSπ2* character and is located at 4.72 eV. Importantly, the values reported in the literature with lower levels of theory33,34 are underestimated and give rise to a different energetic order, where the 1πSπ2 is below 1nOπ6* in these studies. This difference is due to the use of the multistate CASPT2 approach in our work, which allows the correct mixing of the states, in contrast to single-state CASPT2. In the MS-CASPT2 calculations, the interaction of 1πSπ2 with the ground state leads to an increase in energy of 1πSπ2*, whereas 1nOπ6 is down-shifted due to the interaction with 1nSπ6* (S5), leading to the different state ordering. 1πSπ2 carries a significant oscillator strength (0.15, although 0.26 at SS-CASPT2 level) and together with 1πSπ6* is responsible for the double-peak form of the absorption spectrum, as seen in several solvents.25,28,29

The highest computed singlet state (S5) is predicted at 5.16 eV and has 1nSπ6* character. Again, due to the use of MS-CASPT2 (1nSπ6 interacts with 1nOπ6*, leading to a blue shift of 1nSπ6) this state is higher in energy than in the SS-CASPT2 calculations of Gobbo and Borin.34 Because the MS-CASPT2(12,9) calculations do not describe the 1nOπ6* state, no blue-shifting of 1nSπ6 occurs; consequently, the MS-CASPT2(12,9) value is comparable to the SS-CASPT2 value of Gobbo and Borin.34

Table 1 also reports the energies of the lowest triplet states. The lowest triplet state, T1, of 2TU is of 3πSπ2* character at the Franck–Condon geometry; its energy is predicted to be 3.51 eV. This energy is slightly higher than the MS-CASPT2(12,9) result and the value reported by Gobbo and Borin.34 The T2 state is of 3nSπ2 character (and hence the triplet counterpart of S1) and is located at 3.88 eV. The third triplet state T3, with an energy of 4.11 eV, involves an excitation from a π orbital localized on the C5=C6 bond to the antibonding π6*. Finally, the last triplet state calculated, T4, has an energy of 4.85 eV and, being the counterpart of S3, is dominated by 3nOπ6 character. Unlike with the singlet states, all employed methods predict the same energetic ordering of the lowest triplet states.

Compared to the most accurate MS-CASPT2(16,12) results, the MS-CASPT2(12,9) values and the SS ones given by Gobbo and Borin34 systematically predict lower excitation energies, especially for the triplet states. This discrepancy can be largely attributed to the different zero-order Hamiltonian (IPEA shift) used in these calculations. Setting the IPEA shift50 to zero (as in the MS-CASPT2(12,9) calculations and in ref (34)) systematically stabilizes open-shell states and hence predicts excitation energies too low. As shown by some authors,55−57 combining low-quality (double-ζ) basis sets with an IPEA shift of zero can lead to significant error compensation, because small basis sets tend to increase the excitation energy, counteracting the effect of neglecting the IPEA shift. Furthermore, the multistate treatment in our MS-CASPT2(16,12) calculations increases most of the excitation energies, because the ground state is stabilized by the interaction with the 1ππ* states.

Though all the CASPT2 calculations give qualitatively similar results, the MRCIS calculations do not accurately describe the excited states of 2TU, indicating the need of a higher excitation level or a larger reference space. The inclusion of only single excitations is thus not optimal for the excited-state dynamics of 2TU, despite the appealing fact that MRCIS-based dynamics would be much cheaper than CASPT2-based dynamics. One advantage of MRCIS is, though, that it can be used to optimize crossing points including some dynamical correlation (unlike CASSCF), whereas these optimizations are currently not possible with CASPT2.

Notably, the oscillator strength of the ππ* states obtained by the different levels of theory differ considerably. Although MRCIS and ref (34) predict the 1πSπ2* state to be the brightest, the MS-CASPT2(16,12) calculations suggest that the lower-energy 1πSπ6 state is brighter (0.35 for 1πSπ6* vs 0.15 for 1πSπ2). This behavior is due to the MS-CASPT2 treatment, because at SS-CASPT2 the oscillator strengths are approximately equal (0.25 vs 0.26; Table S1 in the Supporting Information). The oscillator strengths were also computed with EOM-CCSD/cc-pvtz using Molpro42,43 (results given in Table S1) and it was found that the lower-energy 1πSπ6* state is also brighter (0.39 vs 0.08), in agreement with the MS-CASPT2(16,12) calculation. Intriguingly, the experimental absorption spectra25,28,29 show two maxima with approximately equal intensity or a band with a shoulder, depending on the solvent. Unfortunately, with the present calculations, it is not possible to distinguish whether the experimental spectrum can be assigned to two states of similar oscillator strengths (and therefore the MS-CASPT2 and EOM-CCSD intensities are incorrect) or due to two states of different oscillator strengths gaining comparable intensity by vibronic effects.

In summary, it was shown that our best MS-CASPT2 vertical excited-state calculations are in excellent agreement with experiment. Smaller-scale MS-CASPT2 calculations, employing smaller basis sets and active spaces, can also describe the lowest excited states reasonably well, although it has to be stressed that this accuracy is partly due to error compensation, where smaller basis sets lead to higher excitation energies, whereas setting the IPEA shift to zero results in lower excitation energies. Furthermore, it has been shown that the inclusion of all relevant orbitals within an MS-CASPT2 calculation is necessary to obtain all excited states and the correct energetic ordering.

In the following, we focus on the relaxation of 2TU after excitation to the lowest bright state, 1πSπ6* (S2). Assuming that the excited states above S2 do not play a role in the deactivation path, they are not included in the MS-CASPT2(12,9) calculations. In the MS-CASPT2(16,12) calculations, higher states are still included to scrutinize that this assumption is correct (Table S2 in the Supporting Information).

Excited-State Minima

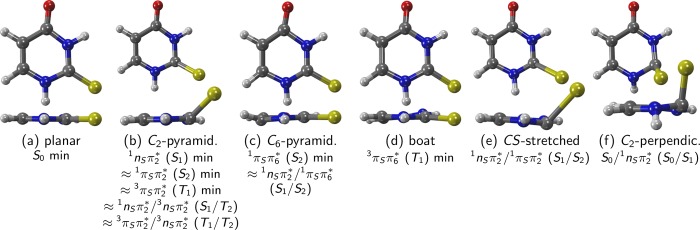

Using MS-CASPT2(12,9), minima for the S0, S1, S2, and T1 states have been optimized. In the case of S2 and T1, two different minima have been found in each state, corresponding to the 1πSπ2* and 1πSπ6, as well as 3πSπ2* and 3πSπ6 characters, hinting at avoided crossings with higher states. The obtained geometries are depicted in Figure 3 and the relevant geometrical parameters are reported in Table 2. To avoid confusion, the columns in the table are labeled according to the wave function character. The energies of all states at all geometries are given in the Supporting Information in Table S2. The optimized geometries are also reported in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Prototypical geometries of the critical points of 2TU. Below the label for each geometry, we list states whose minima/crossings are related to the respective geometry, e.g., the minimum of 1πSπ6* and the 1nSπ2/1πSπ6* crossing have geometries similar to (c).

Table 2. Geometry Parameters for the Excited-State Minima Optimized at the MS-CASPT2(12,9) Level of Theorya.

| exc to π2* |

exc to π6* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | S1 | S2 | T1 | S2 | T1 | |

| 1nSπ2* | 1πSπ2* | 3πSπ2* | 1πSπ6* | 3πSπ6* | ||

| Eb | 0.00 | 3.45 | 3.90 | 3.21 | 3.93 | 3.35 |

| Ec | 0.00 | 3.33 | 3.80 | 2.96 | 3.75 | 2.96 |

| r12 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 1.33 | 1.37 |

| r23 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 1.37 | 1.41 | 1.34 | 1.39 |

| r34 | 1.42 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 1.40 | 1.51 | 1.42 |

| r45 | 1.46 | 1.46 | 1.46 | 1.47 | 1.41 | 1.45 |

| r56 | 1.36 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.38 | 1.43 | 1.45 |

| r61 | 1.38 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.36 | 1.43 | 1.36 |

| r27 | 1.67 | 1.82 | 1.93 | 1.81 | 1.76 | 1.71 |

| r48 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.24 | 1.23 |

| a127 | 122.5 | 117.4 | 110.6 | 110.7 | 120.3 | 120.7 |

| a348 | 120.3 | 120.3 | 120.8 | 121.3 | 114.8 | 120.0 |

| p7213 | –0.1 | 39.1 | 47.3 | 44.5 | –1.9 | 3.0 |

| p8435 | 0.0 | –1.7 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| p10324 | 1.1 | –0.8 | –0.4 | –8.5 | 5.7 | –20.5 |

| p12651 | 0.1 | –0.6 | –0.2 | –0.5 | 26.5 | –5.4 |

| Q | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| B | planar | E2 | E2 | E2 | E6 | B3,6 |

Important parameters are marked in bold. Q is the puckering amplitude;58B is the Boeyens59 symbol for six-membered rings. Energies are in eV, r and Q in Å, and angles a and pyramidalization angles p (defined in the Supporting Information) in degrees. States are labeled according to energetic order (S0, S1, ...) and wavefunction character.

MS(6/4)-CASPT2(16,12)/ano-rcc-vqzp, IPEA = 0.25 au.

MS(4/3)-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pvdz, IPEA = 0.0 au.

We note here that all energies mentioned in the following are from the MS-CASPT2(16,12)/ano-rcc-vqzp calculations, with the MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pvdz energies given in parentheses.

The ground-state geometry (Figure 3a) is nearly planar. The lengths of the C–N bonds (r12, r23, r34, r61, recall Figure 1) are approximately equal, with values from 1.38 to 1.42 Å. The C–C bonds have r45 = 1.46 Å (single bond) and r56 = 1.36 Å (double bond). These and all other bond lengths compare reasonably well to the best-estimate values of ref (40), but our bonds are systematically too long due to the use of a double-ζ basis set in the optimizations.

Compared to the ground-state minimum, the minimum of the 1nSπ2* (S1 state) shows no major differences in the bond lengths, except for the C2=S bond, which is much longer than for S0. The most important geometrical feature of this minimum is the strong pyramidalization at C2, leading to the sulfur atom being strongly displaced out of the molecular plane (Figure 3b). Although the ring itself is still almost planar, a slight puckering of the C2 atom away from the sulfur atom is noticeable (E2 in Boeyens notation59). The S1 energy at its minimum is 3.45 eV (3.33 eV).

The minima of 1πSπ2* (S2) and 3πSπ2 (T1) are structurally very similar to the 1nSπ2* minimum (also Figure 3b), because in all these states the π2 orbital is populated. These minima also feature a mostly planar ring with bond lengths and angles similar to the those of the ground state, a slight puckering and strong pyramidalization at C2 and a strongly enlarged C2=S bond. However, the 1πSπ2* and 3πSπ2 structures show an even larger pyramidalization angle p7213 than the 1nSπ2* minimum. The energies of the 1nSπ2, 1πSπ2*, and 3πSπ2 minima are fairly low (Table 2), and from comparison with the energies of the other minima, it is apparent that C2 pyramidalization is a highly probable process in the deactivation. Surprisingly, however, no C2-pyramidalized geometries were reported in the literature.27,33,34 For completeness, we checked the existence of the C2-pyramidalized minima for T1 and S1 with MRCIS as well as the methods used in ref (34) (SA(6/6)-CASSCF(14,10)/ANO-L-vdzp) and ref (27) (UB3LYP/aug-cc-pvdz, only T1) and found in all cases that the optimizations yielded pyramidalized geometries. One can thus safely assume that C2-pyramidalized minima exist in 2TU, analogous to the ones reported for the related compounds 6-aza-2-thiothymine60 (1nπ*, 3nπ*) and thiourea61 (3nπ*).

We also identified a second minimum on the S2 adiabatic potential energy surface, where the wave function character is 1πSπ6*. This geometry (Figure 3c) features bond inversion (i.e., short bonds become longer and long ones shorter, compared to the ground state) in the ring, an elongated C2=S bond, and puckering and quite notable pyramidalization on C6, due to a weakening of the C=S bond and the increased electron density at C6. The S2 energy at this minimum is 3.93 eV (3.75 eV).

The counterpart on the T1 potential (Figure 3d) with 3πSπ6* character also shows an elongated C5=C6 bond, no bond inversion but pyramidalization at N3, and a slight, boat-like distortion of the ring. The T1 energy at this minimum is 3.35 eV (2.96 eV).

Excited-State Crossing Points

Due to limitations in the existing implementations of the CASPT2 method, it was not possible to optimize crossing points at this level of theory. Instead, crossing points were optimized at CASSCF(14,10)/def2-svp and MRCIS(6,5)/cc-pvdz levels of theory. Because these geometries are not necessarily points of degeneracy at the more accurate CASPT2 level of theory, the crossing geometries were refined with the help of linear interpolation in internal coordinates (LIIC) scans between the CASSCF or MRCIS crossing points and the corresponding CASPT2 minima. Single-point calculations along the LIIC paths were carried out at the MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pVDZ level to locate the geometry with the smallest energy gap between the relevant states. Only at the latter geometries, constituting the best estimate of the crossing point at MS-CASPT2(12,9) level, were the MS-CASPT2(16,12) reference single point calculations performed. Note that we discuss only the MS-CASPT2-refined geometries in the following, but not the geometries optimized at the CASSCF or MRCIS level of theory. The refined geometries are reported in the Supporting Information.

We report first a conical intersection between the 1nSπ2* and 1πSπ6 (S1/S2) states. Because this structure is located close to the 1πSπ6* minimum, it has a very similar geometry, yet featuring a slightly more pronounced pyramidalization at C6 (recall Figure 3c). The geometry was obtained from a LIIC scan between the MS-CASPT2-optimized 1πSπ6 minimum and the CASSCF(14,10)-optimized 1πSπ6*/1nSπ2 crossing point. At the MS-CASPT2(12,9) level of theory, the energies of S1/S2 are 3.79/3.79 eV, which is only 0.04 eV above the 1πSπ6* minimum. Hence, it could be expected that the system very quickly relaxes to S1 after reaching the S2 (1πSπ6) minimum. One should note that the crossing is slightly moved at the more accurate MS-CASPT2(16,12) level of theory, according to the corresponding S1/S2 energies (3.73/3.92 eV).

Another conical intersection between 1nSπ2* and 1πSπ2 (S1/S2) was located on the LIIC between the conical intersection optimized at MRCIS(6,5) level and the MS-CASPT2-optimized 1nSπ2* minimum. The geometry is similar to the ones of the 1nSπ2 and 1πSπ2* minima, featuring strong C2 pyramidalization. However, it is distinguished by a C=S bond length of about 2.3 Å (Figure 3e); at this bond length, the nS and πS orbitals become approximately degenerate, leading to a degeneracy of the 1nSπ2 and 1πSπ2* states. The energies of the involved states are 4.24/4.29 eV (4.07/4.08 eV), making this crossing much less accessible than the previous one. It might, however, be a relaxation pathway for molecules otherwise trapped in the S2 (1πSπ2) minimum.

A conical intersection connecting the 1nSπ2* (S1) with the ground state is depicted in Figure 3f. It was optimized at MRCIS level and shows C2 pyramidalization, but with an even larger pyramidalization angle p7213 of about 56° (α127 is 90°), and also strong pyramidalization at N1. It appears that C2 pyramidalization destabilizes the S0 much more than the S1, which leads to the crossing. This type of perpendicular pyramidalization is also known from other systems, e.g., 6-thioguanine18 or uracil.62 The energies of this S0/S1 crossing are 3.39/3.93 eV (3.56/3.85 eV), showing a significant energy gap between the involved states. However, given the energy of the 1nSπ2 minimum (3.47 eV at MS-CASPT2(16,12), or 3.33 eV at MS-CASPT2(12,9)), this crossing is not expected to be an important relaxation pathway, in agreement with the experimental observation of near-unity ISC yields.28,31,63 In passing, we note that we were not able to reproduce the ethylenic S0/S1 conical intersection described by Gobbo and Borin.34

A minimum energy crossing point between S1 and T2 (3nSπ2*) was found from a LIIC connecting the 1nSπ2 minimum and the S1/T2 crossing optimized at MRCIS level of theory. The energies of S1/T2 are 3.51/3.60 eV (3.42/3.33 eV), which is less than 0.1 eV above the S1 minimum energy. The existence of this singlet–triplet crossing in direct vicinity of the S1 minimum (the geometry is also of C2-pyramidalized type as in Figure 3b and only slightly different from the S1 minimum geometry) is crucial to the very efficient ISC channel in 2TU. At the crossing geometry, the SOC between the involved states is about 130 cm–1, in apparent contradiction to El-Sayed’s rule,64 because both states are of nSπ2* character. However, due to strong nonplanarity, the states involved are not strictly nSπ2, enhancing spin–orbit coupling.

The last crossing found is a conical intersection between 3πSπ2* and 3nSπ2 (T1/T2), which was obtained from a LIIC scan between the MRCIS-optimized T1/T2 crossing and the S1 minimum. This crossing is located at 3.31/3.39 eV (3.21/3.26 eV), slightly below the singlet–triplet crossing described above. Also this geometry is of the C2-pyramidalized type (Figure 3b). This crossing allows for ultrafast internal conversion from 3nSπ2* to 3πSπ2 and subsequent relaxation to the 3πSπ2* minimum. The efficient relaxation to 3πSπ2 and the resulting very small 3nSπ2* population is likely the reason that Pollum and Crespo-Hernández28 did not find any evidence of the 3nSπ2 state.

Reaction Paths

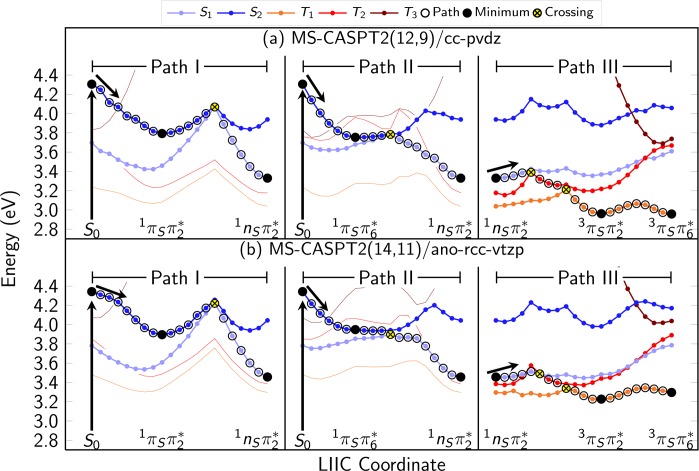

To establish the photodeactivation reaction paths, additional LIIC scans have been carried out to connect the minima and the calculated crossing points. Three chains of LIICs have been constructed: S0 → 1πSπ2* → 1nSπ2/1πSπ2* → 1nSπ2 (Path I); S0 → 1πSπ6* → 1nSπ2/1πSπ6* → 1nSπ2 (Path II), both ending at the S1 minimum; and 1nSπ2* → 1nSπ2/3nSπ2* → 3πSπ2/3nSπ2* → 3πSπ2 → 3πSπ6* (Path III), which leads from the S1 minimum to the T1 minima and hence is the continuation of both Paths I and II. All 59 geometries from the LIIC chains are given in the Supporting Information. The three LIIC chains are depicted side-by-side in Figure 4, together with the assumed relaxation pathway.

Figure 4.

LIIC paths along the critical points of 2-thiouracil. The upper panel (a) shows the MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pvdz energies; the lower panel (b) shows the reference energies from MS-CASPT2(14,11)/ano-rcc-vtzp. Open black circles mark the proposed relaxation pathway, full black circles mark minima discussed in the text, and crosses mark crossing points. The character of the optimized states are given below the fill circles. The black arrows mark the vertical excitation from the ground-state minimum.

The calculations were performed with MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pVDZ and with MS(4/3)-CASPT2(14,11)/ano-rcc-vtzp (with the default IPEA shift). Only the smaller CAS(14,11) active space was used because for C2-pyramidalized geometries the 1nOπ* states are very high in energy and hence the nO orbital could not be kept in the active space along the complete path. For both methods, an imaginary level shift65 of 0.2 au was used to avoid intruder states and to obtain smooth potentials. Figure S2 in the Supporting Information presents the same LIIC paths using single-state CASPT2, showing almost quantitative agreement of SS- and MS-CASPT2. Hence, we are confident that our MS-CASPT2 calculations provide a correct description of the relaxation pathways, without suffering from the possible artifacts of MS-CASPT2 calculations as discussed by Serrano-Andrés et al.66

Due to the presence of two competing minima on the S2 PES—the 1πSπ2* and 1πSπ6 minima—there are two possible relaxation routes (Paths I and II) leading the system away from the Franck–Condon region. Based on static calculations alone, it is not possible to know which S2 minimum is reached after excitation; dynamics simulations are necessary to clarify this issue. However, considering that Path I necessitates the motion of the heavy sulfur atom, it is conceivable that the system will initially follow Path II.

Path II is much more efficient for S2 → S1 internal conversion than Path I. With respect to the 1πSπ6* minimum (Path II), the neighboring S1/S2 conical intersection (1nSπ2/1πSπ6*) is less than 0.1 eV higher in energy, and structurally very similar. Conversely, from the 1πSπ2 minimum (Path I) a barrier of about 0.3 eV needs to be surmounted to reach the S1/S2 crossing point (1nSπ2*/1πSπ2). A slightly smaller barrier separates the two S2 minima; hence it could be possible that trajectories initially following Path I eventually relax through Path II. ISC should not be able to compete with IC at this point in the dynamics because along Path I no triplet states are close in energy to the S2 minimum and relaxation through Path II is expected to be exceptionally fast.

Both Path I and Path II coalesce at the S1 (1nSπ2*) minimum, from where Path III leads to the T1 minima. The S1 PES around the minimum is quite flat and only a very small barrier of 0.05 eV (0.09 eV) needs to be overcome to reach a crossing point with the T2. Because the system should be trapped in the S1 state (the S0/S1 conical intersection is about 0.5 eV above the S1 minimum), it is very likely that 2TU will eventually undergo intersystem crossing to the T2 state. The large SOC and the small energy gap between S1 and T2 support the experimentally observed ISC time scale of 300–400 fs.28

As can be seen in the LIIC scans, from the S1/T2 crossing a barrierless path is available to reach the T1/T2 conical intersection and to immediately decay to T1, followed by relaxation to the T1 (3πSπ2*) minimum. Because both the T1/T2 crossing point and the 3πSπ2 minimum also show C2 pyramidalization, no large atomic motion is necessary to accomplish decay to T1.

However, besides the 3πSπ2* (T1) minimum, a second T1 minimum with 3πSπ6 character and a very similar energy exists. Only a small barrier of about 0.12 eV (0.10 eV) separates the two minima, so that it can be expected that the system will equilibrate between them. Based on quantum chemistry alone, it is not possible to judge how the system will relax to these two minima. The calculated energies of the 3πSπ6* and 3πSπ2 minima are 3.35 and 3.21 eV (2.96 and 2.96 eV) and hence both fit quite well with the value of 3.17 eV of the zero–zero emission of phosphorescence reported by Taherian et al.31 However, the large peak at the zero–zero emission31 of the phosphorescence spectrum might indicate that the geometries of the S0 and the emitting triplet state are not very different, which could be a hint that the emitting triplet is 3πSπ6*. On the contrary, the same authors31 concluded that the T1 minimum is likely to be nonplanar on the basis of the polarization of the phosphorescence emission. Clearly, dynamical simulations are needed to clarify the relative importance of the two T1 minima.

From the computational point of view, it is important to note that the MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pvdz level of theory can reproduce all important features of the excited-state PES, compared to MS-CASPT2(14,11)/ano-rcc-vtzp (Figure 4). Especially the singlet potentials are very similar, whereas the triplet states show slightly larger deviations. For example, around the 1πSπ6* minimum the T2 and T3 states are above the S2 at the MS-CASPT2(14,11) level, whereas they are close to each other at MS-CASPT2(12,9) level. Furthermore, MS-CASPT2(12,9) seems to overstabilize the T1 minima in comparison with the other states, which might be a case where the errors of basis set effect and IPEA shift do not cancel out as it is the case around the Franck–Condon region. In summary, the deviations between MS-CASPT2(12,9) and the larger calculations are acceptable, considering that a MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pvdz single point calculation is about 10 times faster than MS-CASPT2(14,11)/ano-rcc-vtzp and almost 100 times faster than MS-CASPT2(16,12)/ano-rcc-vqzp. One should stress, however, that this close agreement is only due to error compensation in the small calculation, where the increase in excitation energy due to a small basis set (like cc-pvdz) is canceled to a large degree by the effect of setting the IPEA shift to zero. This error compensation is in line with others reported in the literature.55−57

In summary, we then conclude that our calculations indicate S2 → S1 → T2 → T1 to be the primary relaxation pathway for 2TU. We expect direct S2 → S1 → T1 ISC to be only a side channel, because around the S1 minimum the S1–T1 energy gap is always larger than the S1–T2 gap and the S1–T1 SOC is smaller than the S1–T2 SOC (50 and 150 cm–1, respectively). This conclusion is contrary to the findings of Cui and Fang33 and Gobbo and Borin,34 who reported that direct S2 → S1 → T1 ISC should occur. The finding that ISC involves the T2 is not considered by Pollum and Crespo-Hernández,28 who reported S2 → S1 → T1 on the basis of transient absorption spectroscopy. However, the presence of the T1/T2 conical intersection and the small energetic gap between those states allow for ultrafast internal conversion from T2 to T1, with a very low transient T2 population which thus might be hard to observe.

Conclusions

A comprehensive study of the excited-state potential energy surfaces of 2-thiouracil has been reported, employing accurate multireference quantum chemical methods up to MS-CASPT2(16,12), basis sets of up to quadruple-ζ quality and geometries optimized at MS-CASPT2 level. The results show that the lowest S1 minimum is strongly pyramidalized at C2 and that two relaxation paths allow to reach this minimum from the Franck–Condon region. From the S1 minimum, the T2 triplet state can be accessed nearly barrierlessly, and substantial spin–orbit couplings are likely to lead to efficient, subpicosecond ISC. Subsequent relaxation from T2 to T1 is barrierless. The relaxation is expected to ultimately lead to one of two T1 minima, one with a slight boat-like conformation of the pyrimidine ring, the other with C2 pyramidalization. In summary, the photochemical reaction sequence is S2 → S1 → T2 → T1.

As a methodological note, the results from MS-CASPT2(16,12)/ano-rcc-vqzp are compared to MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pvdz, where in the latter calculations the IPEA shift50 was set to zero. The two methods show a very good agreement, all relevant parts of the PES are accurately reproduced by the computationally much more efficient MS-CASPT2(12,9) method. One can therefore conclude that nonadiabatic dynamics simulations at this level of theory should produce an accurate picture of the deactivation of 2TU. Work along these lines is planned for the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) through project P25827, as well as the COST actions CM1204 (XLIC) and CM1305 (ECOSTBio). Part of the calculations have been carried out with the help of the Vienna Scientific Cluster (VSC). Antonio Borin is warmly thanked for providing initial geometries and for fruitful discussions. The authors also want to thank Susanne Ullrich, Carlos Crespo-Hernández, and Inés Corral for related scientific discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b06639.

Definition of pyramidalization angles. Vertical excitation energies, dipole moments, and oscillator strength at CASSCF, SS-CASPT2, MS-CASPT2, and EOM-CCSD levels of theory. Relative energies of all states (S1 to S3, T1 to T3) at all critical points. SS-CASPT2 LIIC paths. XYZ coordinates of all critical points and all coordinates used in Figure 4. References (43), (45), (48), and (49) are provided in complete form as part of the references cited in the Supporting Information. (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Périgaud C.; Gosselin G.; Imbach J. L. Nucleoside Analogues as Chemotherapeutic Agents: A Review. Nucleosides Nucleotides 1992, 11, 903–945 10.1080/07328319208021748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Favre A.; Saintomé C.; Fourrey J.-L.; Clivio P.; Laugâa P. Thionucleobases as intrinsic photoaffinity probes of nucleic acid structure and nucleic acid-protein interactions. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 1998, 42, 109–124 10.1016/S1011-1344(97)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson L. M. Fluorescent nucleic acid base analogues. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2010, 43, 159–183 10.1017/S0033583510000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkeldam R. W.; Greco N. J.; Tor Y. Fluorescent Analogs of Biomolecular Building Blocks: Design, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2579–2619 10.1021/cr900301e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Hernández C. E.; Cohen B.; Hare P. M.; Kohler B. Ultrafast Excited-State Dynamics in Nucleic Acids. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1977–2020 10.1021/cr0206770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton C. T.; de La Harpe K.; Su C.; Law Y. K.; Crespo-Hernández C. E.; Kohler B. DNA Excited-State Dynamics: From Single Bases to the Double Helix. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2009, 60, 217–239 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbatti M., Borin A. C., Ullrich S., Eds. Photoinduced Phenomena in Nucleic Acids; Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollum M.; Martínez-Fernández L.; Crespo-Hernández C. E. In Photoinduced Phenomena in Nucleic Acids I; Barbatti M., Borin A. C., Ullrich S., Eds.; Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2014; Vol. 356, pp 245–327. [Google Scholar]

- Matsika S.Photoinduced Phenomena in Nucleic Acids I; Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2014; Vol. 355, pp 209–243. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Hernández C. E.; Martínez-Fernández L.; Rauer C.; Reichardt C.; Mai S.; Pollum M.; Marquetand P.; González L.; Corral I. Electronic and Structural Elements That Regulate the Excited-State Dynamics in Purine Nucleobase Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4368–4381 10.1021/ja512536c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollum M.; Jockusch S.; Crespo-Hernández C. E. 2,4-Dithiothymine as a Potent UVA Chemotherapeutic Agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17930–17933 10.1021/ja510611j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajitkumar P.; Cherayil J. D. Thionucleosides in transfer ribonucleic acid: diversity, structure, biosynthesis, and function. Microbiol. Rev. 1988, 52, 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines. available from http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/ (accessed July 5, 2015).

- Euvrard S.; Kanitakis J.; Claudy A. Skin Cancers after Organ Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1681–1691 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attard N. R.; Karran P. UVA photosensitization of thiopurines and skin cancer in organ transplant recipients. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 62–68 10.1039/C1PP05194F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran P.; Attard N. Thiopurines in current medical practice: molecular mechanisms and contributions to therapy-related cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 24. 10.1038/nrc2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt C.; Guo C.; Crespo-Hernández C. E. Excited-State Dynamics in 6-Thioguanosine from the Femtosecond to Microsecond Time Scale. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 3263–3270 10.1021/jp112018u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fernández L.; González L.; Corral I. An Ab Initio Mechanism for Efficient Population of Triplet States in Cytotoxic Sulfur Substituted DNA Bases: The Case of 6-Thioguanine. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2134–2136 10.1039/c2cc15775f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fernández L.; Corral I.; Granucci G.; Persico M. Competing Ultrafast Intersystem Crossing and Internal Conversion: a Time Resolved Picture for the Deactivation of 6-Thioguanine. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 1336. 10.1039/c3sc52856a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D. S. Antithyroid Drugs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 905–917 10.1056/NEJMra042972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wätjen F.; Buchardt O.; Langvad E. Affinity therapeutics. 1. Selective incorporation of 2-thiouracil derivatives in murine melanomas. Cytostatic activity of 2-thiouracil arotinoids, 2-thiouracil retinoids, arotinoids, and retinoids. J. Med. Chem. 1982, 25, 956–960 10.1021/jm00350a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basinger M. A.; Casas J.; Jones M. M.; Weaver A. D.; Weinstein N. H. Structural requirements for Hg(II) antidotes. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1981, 43, 1419–1425 10.1016/0022-1902(81)80058-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Komeda K.; Iwamoto S.; Kominami S.; Ohnishi T. Induction of Cell Killing, Mutation and umu Gene Expression by 6-Mercaptopurine or 2-Thiouracil with UVA Irradiation. Photochem. Photobiol. 1997, 65, 115–118 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Párkányi C.; Boniface C.; Aaron J.-J.; Gaye M. D.; Ghosh R.; von Szentpály L.; RaghuVeer K. S. Electronic absorption and fluorescence spectra and excited singlet-state dipole moments of biologically important pyrimidines. Struct. Chem. 1992, 3, 277–289 10.1007/BF00672795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khvorostov A.; Lapinski L.; Rostkowska H.; Nowak M. J. UV-Induced Generation of Rare Tautomers of 2-Thiouracils: A Matrix Isolation Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 7700–7707 10.1021/jp051940e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa H.; Shibl M. F.; Hilal R. Electronic Absorption Spectra of Some 2-Thiouracil Derivatives. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2005, 180, 459–478 10.1080/104265090517181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vendrell-Criado V.; Saez J. A.; Lhiaubet-Vallet V.; Cuquerella M. C.; Miranda M. A. Photophysical properties of 5-substituted 2-thiopyrimidines. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013, 12, 1460–1465 10.1039/c3pp50058f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollum M.; Crespo-Hernández C. E. Communication: The dark singlet state as a doorway state in the ultrafast and efficient intersystem crossing dynamics in 2-thiothymine and 2-thiouracil. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 071101. 10.1063/1.4866447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi-Yamamoto N.; Tajiri A.; Hatano M.; Shibuya S.; Ueda T. Ultraviolet absorption, circular dichroism and magnetic circular dichroism studies of sulfur-containing nucleic acid bases and their nucleosides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Nucleic Acids Protein Synth. 1981, 656, 1–15 10.1016/0005-2787(81)90020-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taras-Goślińska K.; Burdziński G.; Wenska G. Relaxation of the T1 excited state of 2-thiothymine, its riboside and deoxyriboside-enhanced nonradiative decay rate induced by sugar substituent. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2014, 275, 89–95 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2013.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taherian M.-R.; Maki A. Optically detected magnetic resonance study of the phosphorescent states of thiouracils. Chem. Phys. 1981, 55, 85–96 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85087-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi H.; Kobayashi T.; Suzuki T.; Ichimura T. Excited-State Dynamics of 6-Aza-2-thiothymine and 2-Thiothymine: Highly Efficient Intersystem Crossing and Singlet Oxygen Photosensitization. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 8782–8789 10.1021/jp102067t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G.; Fang W.-h. State-specific heavy-atom effect on intersystem crossing processes in 2-thiothymine: A potential photodynamic therapy photosensitizer. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 044315. 10.1063/1.4776261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbo J. P.; Borin A. C. 2-Thiouracil deactivation pathways and triplet states population. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014, 1040–1041, 195–201 10.1016/j.comptc.2014.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M.; Marquetand P.; González-Vázquez J.; Sola I.; González L. SHARC: ab Initio Molecular Dynamics with Surface Hopping in the Adiabatic Representation Including Arbitrary Couplings. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 1253–1258 10.1021/ct1007394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai S.; Marquetand P.; González L. A general method to describe intersystem crossing dynamics in trajectory surface hopping. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2015, 115, 1215. 10.1002/qua.24891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Les A.; Adamowicz L. Tautomerism of 2- and 4-thiouracil. Ab initio theoretical study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 1504–1509 10.1021/ja00160a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rostkowska H.; Szczepaniak K.; Nowak M. J.; Leszczynski J.; KuBulat K.; Person W. B. Thiouracils. 2. Tautomerism and infrared spectra of thiouracils. Matrix-isolation and ab initio studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 2147–2160 10.1021/ja00162a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla M. K.; Leszczynski J. Electronic Transitions of Thiouracils in the Gas Phase and in Solutions: Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT) Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 10367–10375 10.1021/jp0468962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puzzarini C.; Biczysko M.; Barone V.; Pena I.; Cabezas C.; Alonso J. L. Accurate molecular structure and spectroscopic properties of nucleobases: A combined computational-microwave investigation of 2-thiouracil as a case study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 16965–16975 10.1039/c3cp52347k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J. The CASSCF method: A perspective and commentary. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2011, 111, 3267–3272 10.1002/qua.23107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.; Knowles P. J.; Knizia G.; Manby F. R.; Schütz M. Molpro: a general-purpose quantum chemistry program package. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 242–253 10.1002/wcms.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Knowles P. J.; Knizia G.; Manby F. R.; Schütz M.; Celani P.; Korona T.; Lindh R.; Mitrushenkov A.; Rauhut G.; et al. MOLPRO, version 2012.1, a package of ab initio programs. 2012; see https://www.molpro.net/.

- Lischka H.; Müller T.; Szalay P. G.; Shavitt I.; Pitzer R. M.; Shepard R. Columbus - a program system for advanced multireference theory calculations. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2011, 1, 191–199 10.1002/wcms.25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lischka H.; Shepard R.; Shavitt I.; Pitzer R. M.; Dallos M.; Müller T.; Szalay P. G.; Brown F. B.; Ahlrichs R.; Böhm H. J.; et al. COLUMBUS, an ab initio electronic structure program, release 7.0. 2012.

- Pulay P. A perspective on the CASPT2 method. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2011, 111, 3273–3279 10.1002/qua.23052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finley J.; Malmqvist P.-A.; Roos B. O.; Serrano-Andrés L. The Multi-State CASPT2Method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 288, 299. 10.1016/S0009-2614(98)00252-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilante F.; De Vico L.; Ferré N.; Ghigo G.; Malmqvist P.-Å; Neogrády P.; Pedersen T. B.; Pitoňák M.; Reiher M.; Roos B. O.; et al. MOLCAS 7: The Next Generation. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 224–247 10.1002/jcc.21318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlström G.; Lindh R.; Malmqvist P.-Å; Roos B. O.; Ryde U.; Veryazov V.; Widmark P.-O.; Cossi M.; Schimmelpfennig B.; Neogrady P.; et al. MOLCAS: a program package for computational chemistry. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2003, 28, 222–239 10.1016/S0927-0256(03)00109-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghigo G.; Roos B. O.; Malmqvist P.-A. A modified definition of the zeroth-order Hamiltonian in multiconfigurational perturbation theory (CASPT2). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 396, 142–149 10.1016/j.cplett.2004.08.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reiher M. Relativistic Douglas-Kroll-Hess theory. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 139–149 10.1002/wcms.67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roos B. O.; Lindh R.; Malmqvist P.-Å; Veryazov V.; Widmark P.-O. Main Group Atoms and Dimers Studied with a New Relativistic ANO Basis Set. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 2851–2858 10.1021/jp031064+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilante F.; Lindh R.; Bondo Pedersen T. Unbiased auxiliary basis sets for accurate two-electron integral approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 114107. 10.1063/1.2777146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W. C.; Halverstadt I. F. The Dipole Moments of Thiouracil and Some Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 2626–2631 10.1021/ja01188a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozem S.; Huntress M.; Schapiro I.; Lindh R.; Granovsky A. A.; Angeli C.; Olivucci M. Dynamic Electron Correlation Effects on the Ground State Potential Energy Surface of a Retinal Chromophore Model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 4069–4080 10.1021/ct3003139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbatti M.; Ullrich S. Ionization potentials of adenine along the internal conversion pathways. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 15492–15500 10.1039/c1cp21350d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsson O.; Filippi C. Photoisomerization of Model Retinal Chromophores: Insight from Quantum Monte Carlo and Multiconfigurational Perturbation Theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 1275–1292 10.1021/ct900692y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer D.; Pople J. A. General definition of ring puckering coordinates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 1354–1358 10.1021/ja00839a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boeyens J. C. A. The conformation of six-membered rings. J. Cryst. Mol. Struct. 1978, 8, 317. 10.1007/BF01200485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbo J. a. P.; Borin A. C. On The Population of Triplet Excited States of 6-Aza-2-Thiothymine. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 5589–5596 10.1021/jp403508v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur A.; Steer R. P.; Mezey P. G. Ab initio SCF MO calculations of the potential surfaces of thiocarbonyls. III. Ground state and first excited triplet state of thiourea, (NH2)2CS. J. Chem. Phys. 1979, 71, 588–592 10.1063/1.438409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M.; Mai S.; Marquetand P.; González L. Ultrafast Intersystem Crossing Dynamics in Uracil Unravelled by Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 24423. 10.1039/C4CP04158E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milder S. J.; Kliger D. S. Spectroscopy and photochemistry of thiouracils: implications for the mechanism of photocrosslinking in tRNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 7365–7373 10.1021/ja00311a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed M. A. Spin-Orbit Coupling and the Radiationless Processes in Nitrogen Heterocyclics. J. Chem. Phys. 1963, 38, 2834–2838 10.1063/1.1733610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg N.; Malmqvist P.-A. Multiconfiguration perturbation theory with imaginary level shift. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997, 274, 196–204 10.1016/S0009-2614(97)00669-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Andrés L.; Merchán M.; Lindh R. Computation of conical intersections by using perturbation techniques. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 104107. 10.1063/1.1866096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.