Abstract

The differentiation and survival of autoreactive B cells is normally limited by a variety of self-tolerance mechanisms including clonal deletion, anergy and clonal ignorance. The transcription factor c-ets-1 (encoded by the Ets1 gene) has B cell-intrinsic roles in regulating formation of antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) by controlling the activity of Blimp1 and Pax5 and may be required for B cell tolerance to self-antigen. To test this, we crossed Ets1−/− mice to two different transgenic models of B cell self-reactivity, the anti-hen egg lysozyme BCR transgenic strain and the AM14 rheumatoid factor transgenic strain. BCR transgenic Ets1−/− mice were subsequently crossed to mice either carrying or lacking relevant autoantigens. We found that B cells lacking c-ets-1 are generally hyper-responsive in terms of antibody secretion and form large numbers of ASCs even in the absence of cognate antigens. When in the presence of cognate antigen, different responses were noted depending on the physical characteristics of the antigen. We found that clonal deletion of highly autoreactive B cells in the bone marrow was intact in the absence of c-ets1. However, peripheral B cells lacking c-ets-1 failed to become tolerant in response to stimuli that normally induce B cell anergy or B cell clonal ignorance. Interestingly, high affinity soluble self-antigen did cause B cells to adopt many of the classical features of anergic B cells, although such cells still secreted antibody. Therefore, maintenance of appropriate c-ets-1 levels is essential to prevent loss of self-tolerance in the B cell compartment.

Keywords: plasma cell, ignorance, anergy, clonal deletion, Ets1

Introduction

Many B cells produced in the bone marrow rearrange immunoglobulin heavy and light chains that combine to recognize self-antigens, thereby yielding autoreactive B cell receptors (BCRs) (1–3). Several mechanisms exist to eliminate or control the activation of such B cells to minimize the secretion of autoreactive antibodies. Insight into these tolerance processes has been obtained from various BCR transgenic mouse strains that allow analysis of B cell responses to self-antigens under different conditions. Using such strains, it was found that newly-formed autoreactive B cells in the bone marrow can undergo receptor editing in which the immunoglobulin light chain is replaced with a new rearrangement, thus altering the BCR specificity (4–7). If receptor editing is unsuccessful and the BCR retains high affinity and avidity to self-antigen, B cells will undergo apoptosis in the bone marrow (clonal deletion) (8–10). B cells carrying BCRs that recognize lower affinity or lower avidity ligands or ligands not found in the bone marrow may escape these central tolerance programs and be exported to the periphery. These cells can be further tolerized by induction of a non-responsive state (anergy) if continuously stimulated by high-affinity self-antigen. Anergy is characterized by exclusion from the B cell follicle, developmental arrest and shortened life-span (11–15). Alternatively, if the ligand is of lower affinity, is sequestered, or is at too low a concentration, B cells may fail to become overtly activated by the antigen (clonal ignorance) (16–20). Additional checkpoints also exist in the germinal center and in the differentiation pathway to antibody-secreting cells (ASC) (21–25). Furthermore, several non B cell-intrinsic mechanisms exist that restrain the activation of auto-reactive B cells including the limiting availability of the B cell survival factor BAFF and the absence of cognate T cell help.

In mice prone to autoimmunity, B cell tolerance mechanisms are frequently disrupted with the exact outcomes dependent on the particular autoimmune strain and the experimental system chosen. A large number of different genes are thought to affect B cell-intrinsic tolerance mechanisms and the specific roles of some of these genes have been explored by crossing mice deficient in these genes to mice carrying BCR transgenes that allow B cell tolerance responses to be assessed. However, relatively few studies have addressed the need for specific transcription factors in establishing B cell tolerance to self-antigens.

The transcription factor c-ets-1 is expressed at high levels in lymphocytes including B cells, T cells, and NK cells and regulates their functions (26, 27). Loss of the Ets1 gene in mice leads to increased B cell differentiation into IgM and IgG secreting plasma cells and high titers of autoantibodies against common self-antigens such as DNA, histones, and IgG (28, 29). Polymorphisms in the human ETS1 gene are also linked with autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (30–35), rheumatoid arthritis (36, 37), psoriasis (38), ankylosing spondylitis (39), uveitis (40) and celiac disease (41). It is possible that these polymorphisms lead to lower c-ets-1 expression. Indeed, c-ets-1 protein and/or mRNA levels are decreased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from lupus patients and multiple sclerosis patients as compared to controls (42, 43). Thus, decreased expression of c-ets-1 appears to promote autoimmune disease in both mice and humans.

In mice lacking Ets1, the number and function of regulatory T cells is impaired and this contributes to the autoimmune phenotype (29). However, we’ve also shown that Ets1−/− B cells are intrinsically hyper-responsive to TLR9 stimulation (28) and that over-expression of c-ets-1 in purified B cells limits their differentiation to antibody-secreting cells (44, 45). Furthermore, bone marrow chimeras where Ets1−/− B cells develop in the same environment as wild-type B cells demonstrated that the Ets1-deficient cells underwent increased differentiation to plasma cells, indicating a B cell-intrinsic role for c-ets-1 (45). C-ets-1 blocks ASC differentiation by inhibiting the activity of the key ASC differentiation factor Blimp1 and by stimulating the expression of the key B cell identity factor Pax5 (44, 46). We have recently shown that Ets1 expression in B cells is downregulated by activation stimuli, but maintained by inhibitory signaling via a pathway involving Lyn, SHP1 (Ptpn6), CD22, and Siglec-G (45). Given these B cell-intrinsic alterations in Ets1−/− mice, we hypothesized that B cell tolerance to self-antigens might be disrupted in the absence of Ets1. To test this hypothesis, we crossed Ets1 knockout mice to mice carrying specific BCR transgenes that allow the analysis of different mechanisms of B cell tolerance. Specifically, we generated Ets1−/− mice carrying the anti-hen egg lysozyme (MD4) BCR and either soluble or membrane-bound forms of hen egg lysozyme (HEL). We also generated Ets1−/− mice carrying the rheumatoid factor (AM14) BCR in the presence or absence of cognate antigen (IgG2a of the “a” allotype). As described herein, we show using these models that Ets1 is dispensable for tolerance mediated by clonal deletion in the bone marrow, but is required for tolerance via induction of anergy or clonal ignorance.

Materials and Methods

Mice Used

All mice were housed in specific pathogen free environments at the University at Buffalo South Campus Laboratory Animal Facility or at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute’s animal facility in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Ets1-deficient mice used in these studies have been previously described (28, 47). They harbor a neomorphic allele of Ets1 in which exons IV and V are deleted (encoding the Pointed domain) leading to production of a very small amount of internally-deleted c-ets-1 protein lacking the Pointed region (28). However, the allele is functionally a null allele and the phenotype of the mice is identical to mice with another targeted null allele of Ets1 (48). We refer to these mice as Ets-1−/− here. Anti-HEL BCR transgenic mice (MD4 transgene), membrane bound HEL transgenic mice (KLK4 transgene) (8), soluble HEL transgenic mice (ML5 transgene) (11), AM14 immunoglobulin heavy chain transgenic mice (18) and Vκ8 immunoglobulin light chain knockin mice (49) have all been described previously. Both the MD4 and AM14 BCR transgenes used in this study are conventional transgenic receptors. The AM14 heavy chain pairs with the Vκ8 light chain or endogenous light chains to generate a rheumatoid factor BCR that recognizes IgG2a of the “a” allotype, but not the “b” allotype. Mice were genotyped for Ets1, BCR transgenes, HEL antigen and the IgH allotype using PCR. Strains carrying the anti-HEL BCR were maintained on a mixed C57BL/6 x 129Sv genetic background and strains carrying the AM14 BCR on a mixed C57BL/6 x 129Sv x Balb/c genetic background. No attempt to backcross these mice to a more homogeneous background was made, since Ets1−/− mice die at birth on a pure C57BL/6 background (50).

Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared from the bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes of mice and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. The anti-idiotype antibody 4-44, which recognizes the AM14 heavy chain in complex with Vκ8 light chains, has been described (18). The HyHEL-5 antibody, which recognizes an epitope on hen egg lysozyme distinct from that recognized by the anti-HEL BCR, was a kind gift of Dr. Robert Brink (Garvan Institute, Australia). Hen egg lysozyme (Sigma) was labeled with either FITC or Alexa-488 for use in some flow cytometry experiments.

ELISPOT

ELISPOT plates were coated with anti-mouse IgM (clone 11/41, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) to detect rheumatoid factor plasma cells or with purified chicken lysozyme to detect anti-hen egg lysozyme (anti-HEL) plasma cells. Detection antibodies were biotinylated versions of anti-mouse IgM (BD Biosciences), anti-mouse IgMa (BD Biosciences) or 4-44 anti-idiotype antibody. ELISPOT was performed as previously described (46).

ELISA

For ELISA analysis of serum anti-HEL and rheumatoid factor levels, plates were coated in a manner similar to that described above for ELISPOT. Biotinylated detection antibodies (4-44 anti-idiotype (for RF) or anti-mouse IgMa (for anti-HEL)) were used with streptavidin-HRP.

Western Blot Analysis

B cells from the spleen and lymph nodes were purified using negative selection with magnetic beads using either a Miltenyi Biotec or Stem Cell Technologies B cell isolation kits. Purified B cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated using a 1:20 dilution of anti-IgD anti-serum (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or 50 μg/ml anti-IgM (Jackson Immuno-Research). Whole cell lysates were prepared and Western blotted for phosphotyrosine (4G10 antibody, Millipore, Billerica, MA) and GAPDH (clone 6C5, Millipore).

Immunofluorescence

Spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes of mice were harvested and embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura-Finetec, Torrance, CA), frozen on dry ice, and then cut into 7 μm sections. Sections were fixed in cold acetone for 10 minutes and stored at −80°C. Sections were blocked and stained with the anti-idiotype antibody 4-44-biotin along with anti-B220 (anti-CD45R, RA3-6B2)-Alexa 488, anti-CD19 (1D3.2)-Alexa 647, anti-F4/80 (BM8)-Alexa 647 (Caltag) and PNA-FITC (Vector). Antibodies were prepared in the Shlomchik laboratory as previously described (18), except for the anti-F4/80 antibody and the PNA-FITC, which were purchased as indicated above. Streptavidin-Alexa 555 (Molecular Probes) was used as a secondary reagent to detect 4-44-biotin. ProLong Gold Anti-Fade Reagent with DAPI (Molecular Probes) was added to each section. Fluorescent images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U microscope and processed in Adobe Photoshop. Images were blindly scored on a scale of 0–4 based on the intensity of the 4-44 response within follicles and also at extrafollicular foci. Images were scored as 0 for no 4-44+ staining, 1 for very few scattered 4-44+ cells, 2 for a moderate number of 4-44+ cells, 3 for a large number of 4-44+ cells, and 4 for an extensively widespread 4-44+ staining pattern. PNA+ germinal centers, with and without the presence of 4-44+ staining, were enumerated.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of differences between Ets1+/+ and Ets1−/− genotypes was analyzed bypaired or unpaired Student’s t tests.

Results

Ets1 is not required for clonal deletion of autoreactive B cells

Several self-tolerance mechanisms eliminate developing autoreactive B cells in the bone marrow prior to their migration to periphery. These mechanisms include receptor editing and clonal deletion. One classic model of B cell clonal deletion involves mice carrying both a high affinity anti-hen egg lysozyme (anti-HEL) BCR transgene (the MD4 transgene) and a membrane-bound form of ligand (the KLK4 transgene). Because MD4+ B cells cannot undergo receptor editing unless they rearrange endogenous immunoglobulin genes, virtually all B cells are deleted upon their formation in the bone marrow and few B cells are present in the periphery (8). Those B cells that are found in the peripheral tissues fail to bind HEL, indicating that they have rearranged endogenous immunoglobulins. To test whether c-ets-1 is needed for clonal deletion, Ets1−/− mice were crossed to mice carrying the MD4 and KLK4 transgenes

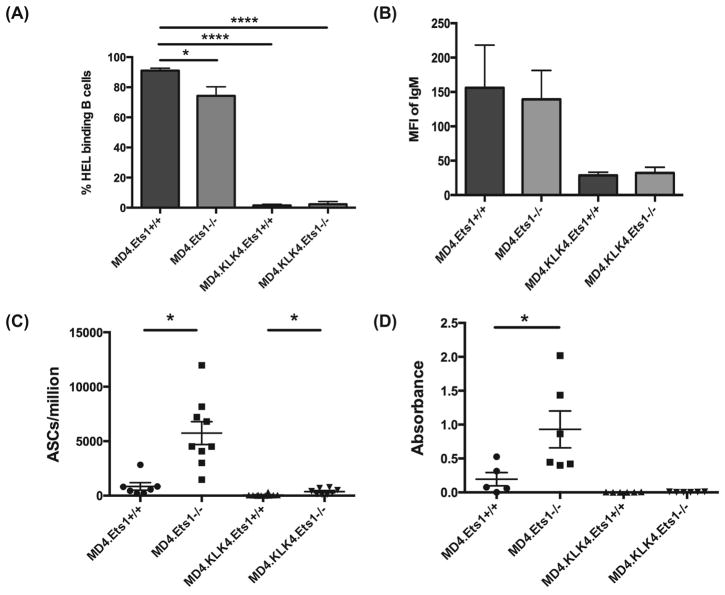

More B220+ B cells were found in the spleens of MD4.KLK4.Ets1−/− mice than MD4.KLK4.Ets1+/+ mice (3.9 ± 1 million for Ets1+/+ versus 12.9 ± 6.6 million for Ets1−/−), although there are still many fewer than in single transgenic MD4+ mice (43 ±18 million for Ets1+/+ versus 95 ± 34 million for Ets1−/−). This potentially could indicate incomplete deletion of HEL-specific immature B cells in the bone marrow in the absence of c-ets-1. However, while most MD4.Ets1+/+ and MD4.Ets1−/− B cells bind HEL, very few MD4.KLK4.Ets1+/+ or MD4.KLK4.Ets1−/− B cells had detectable binding of HEL to their surfaces (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 1A), indicating that the B cells found in the periphery have rearranged endogenous heavy or light chains and are no longer HEL-specific. Examination of surface IgM expression on immature bone marrow B cells where clonal deletion occurs showed that both MD4.KLK4.Ets1+/+ and MD4.KLK4.Ets1−/− immature B cells downregulated surface IgM in response to antigen encounter (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure 1B). Both MD4.KLK4.Ets1+/+ and MD4.KLK4.Ets1−/− mice had very few anti-HEL ASCs in their spleens (Figure 1C). Interestingly, B cells from MD4.Ets1−/− mice were inherently hyperactive in the absence of antigen, because they differentiated to ASCs at much higher rates than MD4.Ets1+/+ mice, even though cognate antigen was absent (Figure 1C). ELISA assay found essentially undetectable levels of anti-HEL antibody in the serum of MD4.KLK4.Ets1−/− mice (Figure 1D). Thus, clonal deletion of B cells with high affinity to a membrane-bound ligand is largely intact in the absence of Ets1.

Figure 1. Clonal deletion is largely intact in mice lacking Ets1.

(A) Percent of B220+ splenic B cells from MD4 single and MD4.KLK4 double transgenic mice that have detectable binding of fluorescently-labeled HEL to their surfaces (n= 6–7 mice of each genotype). (B) Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of IgM on the surface of B220lo IgM+ immature B cells from the bone marrow of the genotypes indicated (n=4 mice of each genotype). (C) ELISPOT analysis of anti-HEL antibody-secreting cells in MD4 and MD4.KLK4 mice (n=7–10 mice of each genotype). (D) ELISA analysis of serum anti-HEL antibody in MD4 and MD4.KLK4 mice (n=6 mice of each genotype). * p<0.05

Ets1-deficient B cells show properties of anergic B cells, but secrete autoantibody

When MD4 transgenic B cells develop in the presence of soluble rather than membrane-bound HEL they do not undergo deletion, but instead are tolerized by induction of clonal anergy. Anergy is dependent on the continuous binding of antigen and results in a non-responsive state. Anergic B cells are characterized by downregulation of surface IgM levels, impaired BCR signaling and, when in competition with other non-anergic B cells, exhibit a shortened life-span and exclusion from the B cell follicle (11, 51–53). To test whether c-ets-1 is needed for induction of an anergic state, MD4.Ets1−/− mice were crossed to mice carrying the soluble HEL transgene (ML5).

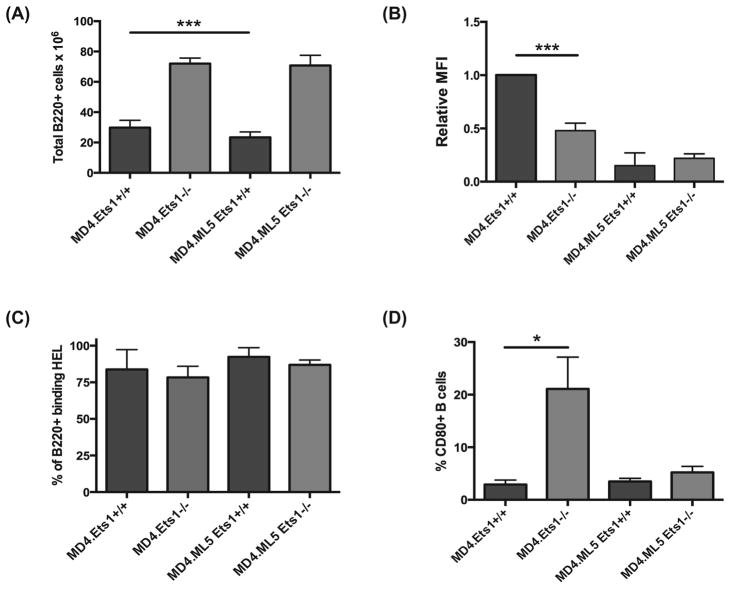

As previously reported, MD4.ML5.Ets1+/+ mice had a reduction in splenic B cells when compared to MD4.Ets1+/+ mice (Figure 2A). MD4.Ets1−/− mice had approximately twice as many B cells in their spleens as did MD4.Ets1+/+ mice. Furthermore, there was no difference in the numbers of B cells in the spleens of MD4.Ets1−/− versus MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− mice (Figure 2A). Anergic B cells have low levels of surface IgM (11). We’ve shown that non-transgenic Ets1−/− splenic B cells also have low surface IgM (28). Consistent with this MD4.Ets1−/− splenic B cells expressed lower levels of surface IgM than MD4.Ets1+/+ B cells (Figure 2B, Supplemental Figure 1C). Both MD4.ML5.Ets1+/+ and MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− B cells also showed low levels of surface IgM expression (Figure 2B). Levels of surface IgD were similar or higher in MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− B cells as compared to control B cells (Supplemental Figure 2B). Virtually all splenic B cells from each genotype bind HEL (Figure 2C, Supplemental Figure 1D), showing that the self-reactive B cells are not deleted nor is there a strong accumulation of B cells with endogenous rearrangements. CD80 is not expressed on anergic B cells of wild-type mice (54), but expression of CD80 is upregulated on non-transgenic Ets1−/− B cells (28). A high percentage of MD4.Ets1−/− B cells expressed surface CD80 (21.1% ± 6.1%) as compared to MD4.Ets1+/+ B cells (2.9% ± 0.8%, p<0.05) (Figure 2D, Supplemental Figure 1E). However, we found that MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− B cells show low levels of CD80, similar to that found in MD4.ML5.Ets1+/+ anergic control B cells (Figure 2C, Supplemental Figure 1E).

Figure 2. Ets1-deficient B cells that bind high affinity soluble antigen develop some features of anergy.

(A) Total numbers of B220+ B cells in the spleens of mice of the indicated genotypes (n= 7–12 mice of each genotype). Grey bars are Ets1−/− mice and black bars are Ets1+/+ mice. (B) Relative mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of IgM on the surface of B220+ B cells from the spleens of the genotypes indicated (n=3–5 mice of each genotype). The average MFI of MD4.Ets1+/+ mice was arbitrarily set to 1 and the remainder of the genotypes are shown relative to this level. (C) Percent of B220+ splenic B cells from MD4 single and MD4.ML5 double transgenic mice that have detectable binding of fluorescently-labeled HEL to their surfaces (n= 3 mice of each genotype). (D) Percent of B220+ splenic B cells that have detectable levels of surface CD80 staining in mice of the indicated genotypes (n= 3–5 mice of each genotype). * p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

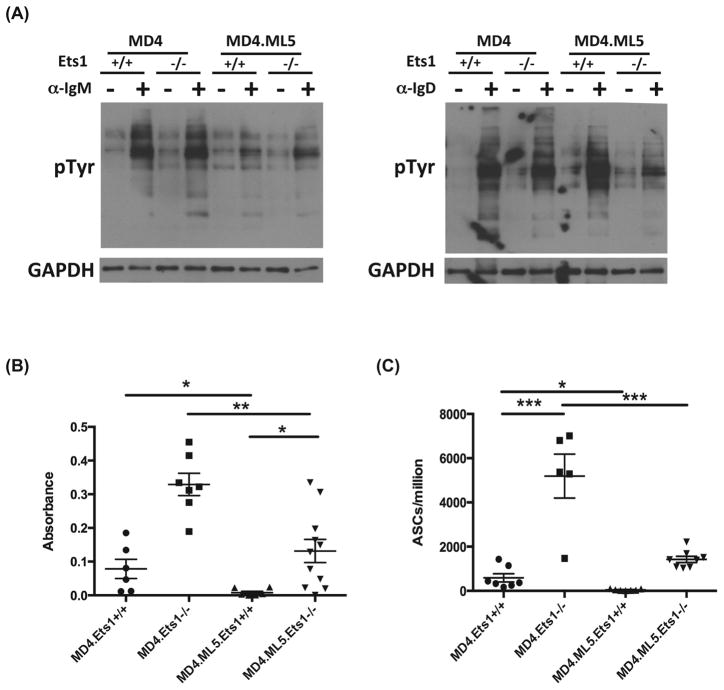

Anergic B cells have impaired BCR signaling as measured by Ca2+ flux and tyrosine phosphorylation following BCR crosslinking by antigen or anti-BCR antibodies (2, 55, 56). To determine if MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− have impaired BCR signaling, we analyzed global protein tyrosine phosphorylation upon crosslinking of the BCR by either anti-IgM or anti-IgD antibodies. As shown in Figure 3A, MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− B cells demonstrated reduced tyrosine phosphorylation, similar to that seen in MD4.ML5.Ets1+/+ B cells. Therefore, MD4.ML5 B cells lacking Ets1 develop many features associated with B cell anergy.

Figure 3. Despite impaired BCR signaling, anergic-like Ets1-deficient B cells develop into ASCs and secrete autoantibody.

(A) Global tyrosine phosphorylation in MD4 single transgenic and MD4.ML5 double transgenic Ets1+/+ and Ets1−/− purified B cells in response to crosslinking the BCR for 5 minutes with either anti-IgM or anti-IgD. Shown is a representative experiment among 8 different experiments. GAPDH staining is shown as a loading control. (B) ELISA analysis of anti-HEL IgMa antibody levels in the serum of mice of the genotypes indicated (n= 6–11 mice of each genotype). (C) ELISPOT analysis of anti-HEL Ig-Ma-secreting ASCs in the spleens of mice of the indicated genotypes (n= 5–8 mice of each genotype). * p<0.05, ** p< 0.01, ***p<0.001.

To determine whether Ets1−/− B cells were functionally anergic in terms of antibody secretion, we measured titers of anti-HEL antibodies. As expected, MD4.ML5.Ets1+/+ lacked serum anti-HEL antibodies indicating an anergic phenotype (Figure 3B). This was further corroborated by absence of anti-HEL ASCs (Figure 3C). In contrast, MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− mice had anti-HEL antibody in their serum and anti-HEL ASCs in their spleens, indicating a breach in B cell tolerance (Figure 3B–C). However, the levels of anti-HEL antibodies and plasma cells in MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− mice were reduced as compared to those in MD4.Ets1−/− mice.

Ets1 is essential for maintaining B cell clonal ignorance

To determine whether c-ets-1 is needed for B cell clonal ignorance to a low affinity ligand, we crossed Ets1−/− mice to mice carrying an immunoglobulin heavy chain transgene (the AM14 transgene), which when paired with appropriate light chains generates a BCR with rheumatoid factor (RF) low affinity towards IgG2a of the “a” allotype. The AM14 BCR does not recognize IgG2a of the “b” allotype. Thus, the availability of self-antigen can be controlled by breeding to genetic backgrounds carrying either the IgHa or IgHb immunoglobulin allotype.

When mice carrying the AM14 heavy chain transgene are crossed to mice carrying a particular targeted knock-in allele of a pre-rearranged Ig Vκ8 light chain essentially all B cells have RF-specificity (18). Alternatively, in mice carrying only the AM14 heavy chain, B cells rearrange endogenous light chains, including some light chains very similar to the knockin Vκ8 chain, resulting in a polyclonal repertoire with ~3–5% of B cells having RF specificity (57). Whether using the pre-rearranged Vκ8 light chain knockin or endogenous light chain rearrangements, the RF-specific B cells can be identified using an idiotype-specific antibody 4-44 (57). We have analyzed Ets1−/− mice carrying only the AM14 heavy chain (designated AM14.Ets1−/−) as well as Ets1−/− mice carrying both the AM14 heavy chain and Vκ8 knockin light chain (designated AM14.Vκ8.Ets1−/−). We selected progeny for analysis that either carried the self-antigen or lacked it using IgH allotype-specific PCR. Data from analyses of mice carrying both the AM14 heavy chain and the Vκ8 light chain are shown in most of the figures below, but very similar results were obtained from mice carrying the AM14 heavy chain alone.

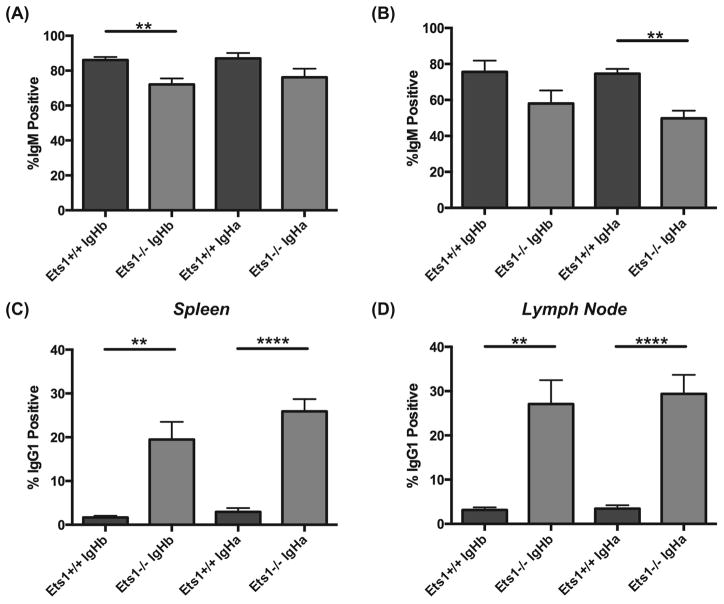

It has previously been shown that the AM14 BCR transgene mediates efficient allelic exclusion (16, 18). However, analysis of B220/IgM profiles in AM14.Vκ8.Ets1−/− mice and AM14.Ets1−/− mice showed that a significant fraction of peripheral B cells, particularly in the lymph node, did not express surface IgM (the isotype of the AM14 heavy chain transgene) (Figure 4A–B, Supplemental Figure 2A–B).

Figure 4. IgG1+ B cells accumulate in the periphery of AM14 transgenic Ets1−/− mice.

Percent of B220+ B cells in the spleens (A) and lymph nodes (B) of AM14.Vκ8 BCR transgenic mice (Ets1+/+ and Ets1−/−) harboring either an IgHa or IgHb genetic background that have detectable surface IgM staining. Note the reduced percentages of IgM-positive B cells in Ets1−/− mice. Percent of B220+ B cells in the spleens (C) and lymph nodes (D) of AM14.Vκ8 BCR transgenic mice (Ets1+/+ and Ets1−/−) harboring either an IgHa or IgHb genetic background that have detectable surface IgG1 staining. Note the strongly increased percentages of IgG1-positive B cells in Ets1−/− mice. ** p< 0.01, ****p<0.0001.

Instead AM14.Vκ8.Ets1−/− mice and AM14.Ets1−/− mice had an expanded population of B cells carrying surface IgG1 (Figure 4C–D, Supplemental Figure 2C–D). Indeed, 20–30% of all B cells in spleen and lymph nodes of AM14+ Ets1-deficient mice expressed surface IgG1. In mice carrying both the AM14 and Vκ8 transgenes, up to 50–55% of lymph node B cells expressed surface IgG1. Only a small proportion of B cells in any of the genotypes co-expressed IgM and IgG1, suggesting that the AM14 transgene is silenced in cells that rearrange endogenous immunoglobulins and switch to IgG1. IgG1+ B cells were present in both IgHa and IgHb genetic backgrounds and hence not dependent on stimulation via cognate antigen.

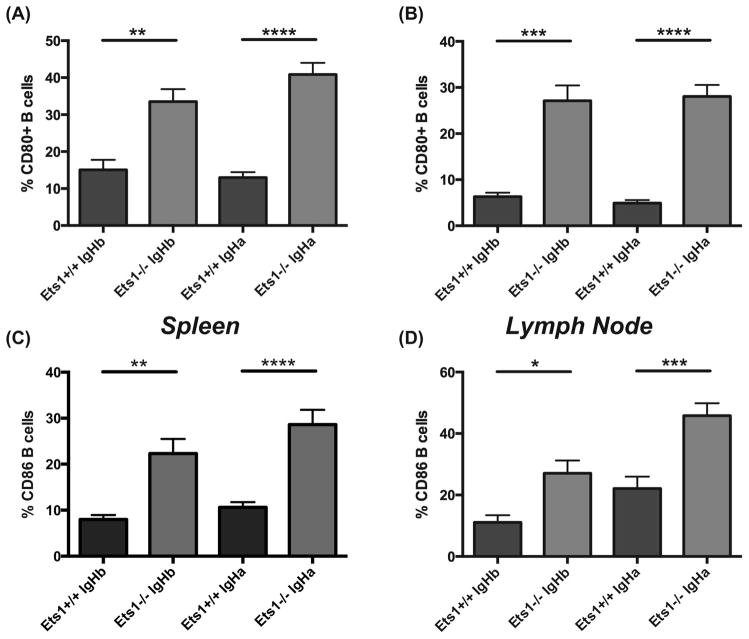

B cells from AM14.Vκ8.Ets1−/− mice and AM14.Ets1−/− mice expressed high levels of surface CD80 and CD86, indicating they were activated (Figure 5A–D, Supplemental Figure 2E–F and Supplemental Figure 3A–B). However, the upregulation of CD80 and CD86 did not require the presence of cognate antigen, since B cells derived from both IgHa and IgHb genetic backgrounds showed enhanced CD80 and CD86 staining. Furthermore, CD80 staining was increased on both 4-44pos and 4-44neg B cells from Ets1−/− mice (Supplemental Figure 3C).

Figure 5. AM14 transgenic B cells in Ets1−/− mice express increased surface CD80 and CD86.

Percent of B220+ B cells in the spleens (A) and lymph nodes (B) of AM14.Vκ8 BCR transgenic mice (Ets1+/+ and Ets1−/−) harboring either an IgHa or IgHb genetic background that have detectable surface CD80 staining. Percent of B220+ B cells in the spleens (C) and lymph nodes (D) of AM14.Vκ8 BCR transgenic mice (Ets1+/+ and Ets1−/−) harboring either an IgHa or IgHb genetic background that have detectable surface CD86 staining. * p<0.05, ** p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

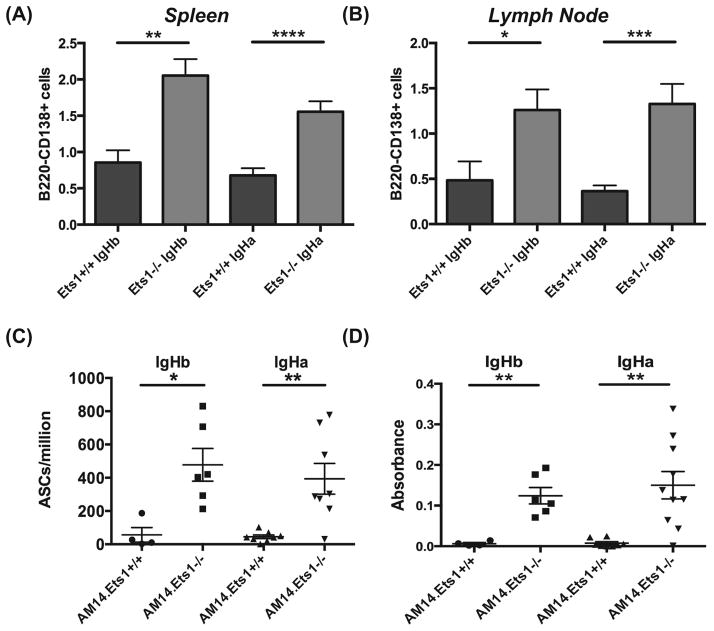

Cells with an antibody-secreting cell phenotype (B220low/negCD138+ cells in flow cytometry) were increased in the spleens and lymph nodes of AM14.Vκ8.Ets1−/− mice and AM14.Ets1−/− mice (Figure 6A–B, Supplemental Figure 3D–E). To further confirm the presence of antibody-secreting cells, we performed ELISPOT assays on splenocytes to detect idiotype-secreting (4-44-binding) cells and found a dramatic increase in the numbers of RF antibody-secreting cells in AM14.Vκ8.Ets1−/− mice and in AM14.Ets1−/− mice as compared to AM14.Vκ8.Ets1+/+ mice and AM14.Ets1+/+ mice (Figure 6C and not shown). Similar to what we observed with CD80 and CD86 expression, the increase in ASC differentiation does not appear to require antigen as AM14.Vκ8.Ets1−/− mice and AM14.Ets1−/− mice on IgHb genetic backgrounds show similar numbers of RF-secreting cells. However, by ELISA the level of RF antibodies was somewhat lower in AM14.Ets1−/− mice lacking antigen than in AM14.Ets1−/− mice carrying autoantigen (Figure 6D), although this difference was not statistically-significant. Altogether these results indicate that AM14+ Ets1−/− B cells are spontaneously activated in the apparent absence of cognate ligand and undergo differentiation into antibody-secreting cells.

Figure 6. AM14 transgenic B cells in Ets1−/− mice are not clonally ignorant.

Increased numbers of cells with an antibody-secreting phenotype (B220negCD138hi) in the spleens (A) and lymph nodes (B) of AM14.Vκ8.Ets1−/− as compared to controls (n= 7–19 mice of each genotype). (C) Quantitation of idiotype (4-44) positive RF antibody-secreting cells by ELISPOT in AM14 mice (n= 4–10 mice of each genotype). (D) Quantitation of idiotype (4-44) positive RF antibody by ELISA (n= 4–10 mice of each genotype). * p<0.05, ** p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

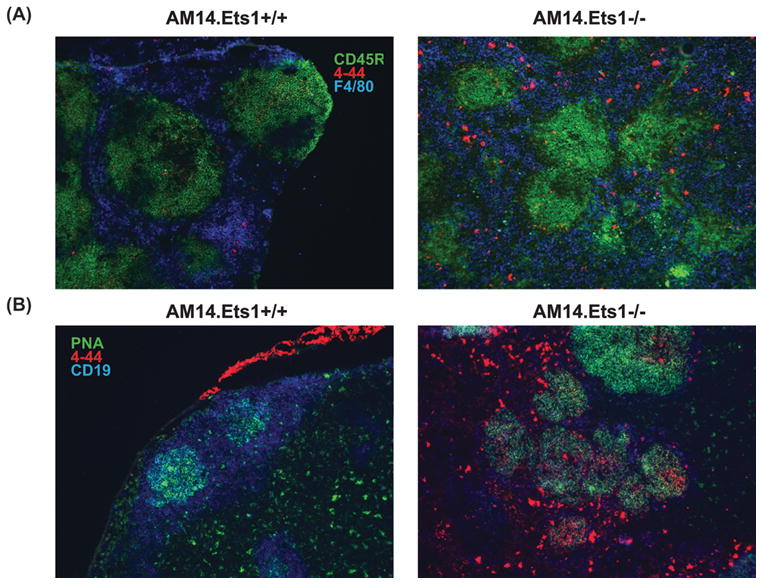

AM14 B cells lacking Ets1 undergo differentiation in extrafollicular locations

Autoreactive RF B cells in an MRL/Faslpr genetic background can be activated and differentiate to plasmablasts (57–59). In fact, these cells undergo proliferation, isotype-switching, somatic hypermutation and differentiation into antibody-secreting cells at the border of the T cell zone and red pulp, but do not form AM14+ germinal centers. Similarly in autoimmune Sle1.2.3 triple congenic and Act1−/− mice, AM14+ plasmablasts are localized in the red pulp, although in these strains some AM14+ cells also form germinal centers (60, 61). To determine if AM14+ B cells lacking Ets1 showed a similar extrafollicular response, we examined the ASC response in the spleen and lymph nodes of AM14.Ets1−/− mice using immunofluorescent staining for idiotype-positive cells. Antibody-secreting cells can be detected in sections of spleen or lymph node as large 4-44bright cells that stain weakly with anti-B220 antibody. In the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of AM14.Ets1−/− mice we detected a strong RF ASC response (large 4-44bright B220neg cells) localized at the red pulp/T cell zone border (Figures 7A and Supplemental Figure 4A). Cognate antigen (IgG2aa) is not required for the extrafollicular ASC response, although it appears to modestly stimulate the response in the lymph nodes (Supplemental Figure 4B). B cells that presumably carried endogenous immunoglobulin rearrangements because they failed to stain with the 4-44 anti-idiotype antibody were localized in the follicles in AM14.Ets1−/− mice (Figure 7A). Therefore, the vast majority of RF B cells in Ets1−/− mice have differentiated into ASCs in extrafollicular sites. In contrast, but similar to what has previously been reported for AM14+ MRL/Faslpr mice, few RF B cells are found in the germinal center in AM14.Ets1−/− mice (Figure 7B and Supplemental Figure 7C–D).

Figure 7. RF-specific B cells in Ets1−/− mice differentiate to ASC at extrafollicular sites.

(A) Immunofluorescent staining of spleen sections from AM14.Ets1+/+ and AM14.Ets1−/− mice with antibodies to B220 (CD45R, green), idiotype (4-44, red) and the macrophage marker F4/80 (blue) demonstrates accumulation of B220low4-44bright ASC in an extrafollicular location in the Ets1−/− sample (n = 7–12 mice of each genotype). (B) Immunofluorescent staining of mesenteric lymph node sections with antibodies to CD19 (blue) and idiotype (4-44, red) and with PNA (green) to identify germinal centers (n= 6–12 mice of each genotype). Most 4-44+ B cells are located outside germinal centers.

Discussion

The current study addresses the previously-unanswered question of whether c-ets-1 plays an important role in maintaining B cell tolerance to self-antigens. We found that c-ets-1 is crucial for aspects of peripheral B cell tolerance. The contribution of c-ets-1 to these B cell tolerance mechanisms is likely important to its role in preventing autoimmunity in humans and in mice. Specifically, we found that deletion of the Ets1 gene does not prevent tolerance induced by clonal deletion of immature B cells in response to a high affinity membrane-bound ligand. This is likely because MD4.KLK4.Ets1−/− B cells undergo apoptosis too rapidly to allow them to differentiate into autoantibody-secreting plasma cells. Similarly, clonal deletion is also intact on an autoimmune MRL.lpr genetic background (62). In contrast, this form of B cell tolerance can be broken by alteration of the levels of pro- or anti-apoptotic proteins (63, 64). The fact that clonal deletion is intact in Ets1−/− B cells suggests that they do not have a defect in the induction of apoptosis.

Although clonal deletion was intact, peripheral B cell tolerance induction by anergy was defective in Ets1-deficient B cells. We found that cognate antigen was not required for Ets1−/− B cells to differentiate into ASCs, as MD4.Ets1−/− B cells showed a high level of differentiation in the absence of HEL. Thus, B cells lacking c-ets-1 have an innate propensity to become ASCs whether or not they encounter antigen. This innate propensity to differentiate will result in secretion of autoantibody that could then bind and sequester antigen, resulting in reduced tolerance inducing activity and may therefore further amplify the escape from anergy. C-ets-1 was not needed for induction of many classical features of B cell anergy (downregulation of surface IgM, low levels of surface CD80 and impaired BCR signaling). However, c-ets-1 was essential to prevent ASC formation and autoantibody secretion by B cells that have adopted an anergic phenotype. Therefore anergy has separable sub-phenotypes in that ASC formation can be uncoupled from certain phenotypic manifestations. Interestingly, B cells from NZB autoimmune mice carrying the MD4 and ML5 transgenes have also been reported to adopt an anergic phenotype, but to still differentiate into ASCs (65). This was attributed to enhanced B cell responsiveness to BAFF and to the provision of T cell help by non-tolerant NZB T cells.

Signaling via the tyrosine kinase Lyn, which results in the recruitment of the phosphatase SHP1 to CD22 and Siglec-G, is crucial to maintain c-ets-1 levels in B cells (45). Thus, we would anticipate some overlap in the phenotypes of Lyn−/−, Ptpn6−/− (SHP1-deficient) and Ets1−/− B cells carrying the MD4 transgene. Indeed, like single-transgenic MD4.Ets1−/− B cells, single-transgenic MD4.Lyn−/− and MD4.Ptpn6−/− B cells show spontaneous differentiation into anti-HEL secreting plasma cells (66, 67). However, in the presence of cognate antigen both MD4.ML5.Lyn−/− and MD4.ML5.Ptpn6−/− B cells show exaggerated tolerance in which autoreactive B cells are deleted in response to soluble high affinity self-antigen (66, 67). The exaggerated tolerance of MD4.ML5.Lyn−/− and MD4.ML5.Ptpn6−/− B cells is thought to be due to increased BCR signaling. Since loss of Ets1 does not significantly affect BCR signaling, there is no increased clonal deletion of MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− B cells.

C-ets-1 is also essential for B cells to remain clonally ignorant in response to low affinity antigen. Similar to the case with MD4.Ets1−/− B cells, AM14.Ets1−/− B cells did not appear to require cognate antigen to undergo differentiation to ASCs. This contrasts with the situation that has been found in MRL.lpr, Sle1.2.3 and Act1−/− backgrounds where AM14+ B cells only differentiate to ASCs when cognate antigen is present (60, 61, 68). However, this is complicated by the fact that the AM14 BCR may be capable of recognizing an additional as-yet-unknown endogenous ligand found in the C57BL/6 genetic background, but not in the Balb/c background (personal communication, Dr. Ann Marshak-Rothstein). The mice we used in our studies were of a mixed genetic background including some contribution of C57BL/6. We used this mixed background, because Ets1-deficient mice die soon after birth on a pure C57BL/6 background (48). Because the identity of the potential endogenous ligand for AM14 is unknown, we were not able to test whether our mixed background mice carried this antigen. Hence, we cannot exclude that it might contribute to breaking B cell tolerance. However, any endogenous C57BL/6 endogenous ligand would likely be present in only a subset of AM14+ Ets1−/− mice and, if it contributed to B cell activation, would result in two sub-groups of mice one showing B cell activation and the other not. We did not observe this and instead found all AM14.Ets1−/− and AM14.Vk8.Ets1−/− mice showed B cell activation and secretion of rheumatoid factor antibodies. Furthermore, based on the results obtained with anti-HEL Ets1−/− mice, where there are no endogenous ligands for the BCR, we think it is highly likely that the presence of antigen is not required for AM14+ B cell differentiation to ASCs in the absence of Ets1.

In the MRL.lpr background AM14+ plasmablasts differentiate in a T cell-independent fashion at the border of the red pulp, but relatively few are found in germinal centers (57). In contrast, AM14+ cells contribute both to extrafollicular plasmablasts and to germinal centers in Sle1.2.3 and Act1−/− backgrounds (60, 61). In Ets1-deficient mice, we found the ASC responses to be more similar to those of MRL.lpr mice with AM14+ plasmablasts found in the red pulp of the spleen and in medullary cords of the lymph node, while very few were present in the germinal centers.

Increased serum concentrations of IgG1 have been noted in Ets1−/− mice (48). We found that ~7% of non-transgenic Ets1−/− B cells carry surface IgG1, while only ~1% of non-transgenic Ets1+/+ B cells carry this isotype (data not shown). We observed a striking increase in IgG1+ B cells in Ets1−/− mice carrying the AM14 BCR (either with or without IgG2aa antigen, but potentially carrying an endogenous C57BL/6-derived antigen). Ets1−/− thymocytes are known to exhibit defects in allelic exclusion at the TCRβ locus (48) and there could also be similar defects in allelic exclusion in B cells. However, relatively few B cells co-expressed both the transgenic BCR and IgG1 and a defect in allelic exclusion would be expected to show up in anti-HEL BCR transgenic Ets1−/− mice as well. Hence, it seems more likely that allelic exclusion is largely intact in Ets1−/− B cells. Instead, in some developing B cells the transgenic AM14 heavy chain may get silenced, allowing a few endogenously rearranged B cells to be generated and these cells may expand and switch to IgG1 in the periphery under appropriate conditions.

Switching to IgG1 is promoted by Th2 cytokines. CD4+ T cells isolated ex vivo from the spleen of Ets1−/− mice have been shown to produce high levels of Th2 cytokines (29). Potentially, AM14+ Ets1−/− mice might have even further increased levels of Th2 cytokines as compared to non-transgenic Ets1−/− mice. One model could be that in AM14+ Ets1−/− mice, the high fraction of B cells expressing surface CD80 and CD86 leads to polyclonal activation of T cells, which in the absence of c-ets-1 are skewed to Th2 development. These T cells could then interact with the few B cells that carry endogenous rearrangements to cause their expansion and isotype-switching. An alternate explanation of increased IgG1 levels in AM14+ Ets1−/− mice is the genetic background of the strain. Both non-transgenic Ets1−/− mice and MD4+ Ets1−/− mice have been maintained on a mixed C57BL/6 x 129Sv genetic background (because Ets1−/− mice die perinatally on a pure C57BL/6 background). In contrast, AM14+ Ets1−/− mice were maintained on a mixed C57BL/6 x 129Sv x Balb/c background. The Balb/c genetic background is known to be skewed towards a Th2 phenotype. Because the main focus of this research was on understanding the role of c-ets-1 in B cell tolerance not its role in regulation of isotype switching, we did not further pursue the mechanisms driving switching of Ets1−/− B cells to IgG1. However, we will address this in future studies.

The responses of MD4+ Ets1−/− B cells and AM14+ Ets1−/− B cells differed in that the presence of high-affinity soluble antigen in MD4+ Ets1−/− mice suppressed the ASC response, while the presence of low-affinity antigen in AM14+ Ets1−/− mice either had no effect or slightly stimulated the response. Likely this difference can be explained by the fact that MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− B cells develop anergic-like properties, while AM14+ Ets1−/− IgHa B cells do not. The induction of an anergic-like phenotype in MD4.ML5.Ets1−/− B cells may lead to a shorter B cell life-span, thus limiting their ability to differentiate into plasma cells. Another possibility to explain the different responses is that the AM14 autoantigen (IgG2aa) is often found in complexes with self-TLR ligands (DNA and RNA containing apoptotic cell debris), whereas the MD4 autoantigen (soluble HEL) is not known to form such complexes. The presence of TLR ligands in the autoantigen recognized by the AM14 BCR might provide additional co-stimulatory signals that function to promote secretion of autoantibodies. However, there was no difference in ASC numbers between AM14+ Ets1−/− mice whether cognate antigen was present or not, suggesting that BCR-mediated internalization of TLR ligands might not play a role in B cell activation under these circumstances.

Collectively in this study, we have shown that c-ets-1 is crucial to prevent B cell differentiation to autoantibody-secreting cells in situations where B cells would normally be anergic or clonally ignorant. In contrast, c-ets-1 does not appear to be required for clonal deletion of highly autoreactive B cells in the bone marrow. Importantly, this study also indicates that induction of an anergic phenotype in B cells is not sufficient to prevent their differentiation to antibody-secreting cells if c-ets-1 is absent. This establishes that c-ets-1 plays a central role in the process of maintaining B cell quiescence and suggests that methods to stabilize or restore c-ets-1 in B cells could be used to limit their differentiation to autoantibody-secreting cells.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merrell KT, Benschop RJ, Gauld SB, Aviszus K, Decote-Ricardo D, Wysocki LJ, Cambier JC. Identification of anergic B cells within a wild-type repertoire. Immunity. 2006;25:953–962. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souroujon M, White-Scharf ME, Andreschwartz J, Gefter ML, Schwartz RS. Preferential autoantibody reactivity of the preimmune B cell repertoire in normal mice. J Immunol. 1988;140:4173–4179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiegs SL, Russell DM, Nemazee D. Receptor editing in self-reactive bone marrow B cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1009–1020. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gay D, Saunders T, Camper S, Weigert M. Receptor editing: an approach by autoreactive B cells to escape tolerance. J Exp Med. 1993;177:999–1008. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halverson R, Torres RM, Pelanda R. Receptor editing is the main mechanism of B cell tolerance toward membrane antigens. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:645–650. doi: 10.1038/ni1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hippen KL, Schram BR, Tze LE, Pape KA, Jenkins MK, Behrens TW. In vivo assessment of the relative contributions of deletion, anergy, and editing to B cell self-tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;175:909–916. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartley SB, Crosbie J, Brink R, Kantor AB, Basten A, Goodnow CC. Elimination from peripheral lymphoid tissues of self-reactive B lymphocytes recognizing membrane-bound antigens. Nature. 1991;353:765–769. doi: 10.1038/353765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Shlomchik MJ. High affinity rheumatoid factor transgenic B cells are eliminated in normal mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:1125–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nemazee DA, Burki K. Clonal deletion of B lymphocytes in a transgenic mouse bearing anti-MHC class I antibody genes. Nature. 1989;337:562–566. doi: 10.1038/337562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Wotherspoon JS, Loblay RH, Raphael K, et al. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;334:676–682. doi: 10.1038/334676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erikson J, Radic MZ, Camper SA, Hardy RR, Carmack C, Weigert M. Expression of anti-DNA immunoglobulin transgenes in non-autoimmune mice. Nature. 1991;349:331–334. doi: 10.1038/349331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandik-Nayak L, Bui A, Noorchashm H, Eaton A, Erikson J. Regulation of anti-double-stranded DNA B cells in nonautoimmune mice: localization to the T-B interface of the splenic follicle. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1257–1267. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benschop RJ, Aviszus K, Zhang X, Manser T, Cambier JC, Wysocki LJ. Activation and anergy in bone marrow B cells of a novel immunoglobulin transgenic mouse that is both hapten specific and autoreactive. Immunity. 2001;14:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrero M, Clarke SH. Low-affinity anti-Smith antigen B cells are regulated by anergy as opposed to developmental arrest or differentiation to B-1. J Immunol. 2002;168:13–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannum LG, Ni D, Haberman AM, Weigert MG, Shlomchik MJ. A disease-related rheumatoid factor autoantibody is not tolerized in a normal mouse: implications for the origins of autoantibodies in autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1269–1278. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adelstein S, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Anderson TA, Crosbie J, Gammon G, Loblay RH, Basten A, Goodnow CC. Induction of self-tolerance in T cells but not B cells of transgenic mice expressing little self antigen. Science. 1991;251:1223–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.1900950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shlomchik MJ, Zharhary D, Saunders T, Camper SA, Weigert MG. A rheumatoid factor transgenic mouse model of autoantibody regulation. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1329–1341. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.10.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koenig-Marrony S, Soulas P, Julien S, Knapp AM, Garaud JC, Martin T, Pasquali JL. Natural autoreactive B cells in transgenic mice reproduce an apparent paradox to the clonal tolerance theory. J Immunol. 2001;166:1463–1470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandik-Nayak L, Racz J, Sleckman BP, Allen PM. Autoreactive marginal zone B cells are spontaneously activated but lymph node B cells require T cell help. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1985–1998. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul E, Lutz J, Erikson J, Carroll MC. Germinal center checkpoints in B cell tolerance in 3H9 transgenic mice. Int Immunol. 2004;16:377–384. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Culton DA, O’Conner BP, Conway KL, Diz R, Rutan J, Vilen BJ, Clarke SH. Early preplasma cells define a tolerance checkpoint for autoreactive B cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:790–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.William J, Euler C, Primarolo N, Shlomchik MJ. B cell tolerance checkpoints that restrict pathways of antigen-driven differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;176:2142–2151. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahman ZS, Alabyev B, Manser T. FcgammaRIIB regulates autoreactive primary antibody-forming cell, but not germinal center B cell, activity. J Immunol. 2007;178:897–907. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiller T, Kofer J, Kreschel C, Busse CE, Riebel S, Wickert S, Oden F, Mertes MM, Ehlers M, Wardemann H. Development of self-reactive germinal center B cells and plasma cells in autoimmune Fc gammaRIIB-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2767–2778. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell L, Garrett-Sinha LA. Transcription factor Ets-1 in cytokine and chemokine gene regulation. Cytokine. 2010;51:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrett-Sinha LA. Review of Ets1 structure, function, and roles in immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:3375–3390. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D, John SA, Clements JL, Percy DH, Barton KP, Garrett-Sinha LA. Ets-1 deficiency leads to altered B cell differentiation, hyperresponsiveness to TLR9 and autoimmune disease. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1179–1191. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mouly E, Chemin K, Nguyen HV, Chopin M, Mesnard L, Leitede-Moraes M, Burlen-Defranoux O, Bandeira A, Bories JC. The Ets-1 transcription factor controls the development and function of natural regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2113–2125. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan KE, Piliero LM, Dharia T, Goldman D, Petri MA. 3′ polymorphisms of ETS1 are associated with different clinical phenotypes in SLE. Hum Mutat. 2000;16:49–53. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200007)16:1<49::AID-HUMU9>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han JW, Zheng HF, Cui Y, Sun LD, Ye DQ, Hu Z, Xu JH, Cai ZM, Huang W, Zhao GP, Xie HF, Fang H, Lu QJ, Li XP, Pan YF, Deng DQ, Zeng FQ, Ye ZZ, Zhang XY, Wang QW, Hao F, Ma L, Zuo XB, Zhou FS, Du WH, Cheng YL, Yang JQ, Shen SK, Li J, Sheng YJ, Zuo XX, Zhu WF, Gao F, Zhang PL, Guo Q, Li B, Gao M, Xiao FL, Quan C, Zhang C, Zhang Z, Zhu KJ, Li Y, Hu DY, Lu WS, Huang JL, Liu SX, Li H, Ren YQ, Wang ZX, Yang CJ, Wang PG, Zhou WM, Lv YM, Zhang AP, Zhang SQ, Lin D, Low HQ, Shen M, Zhai ZF, Wang Y, Zhang FY, Yang S, Liu JJ, Zhang XJ. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1234–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He CF, Liu YS, Cheng YL, Gao JP, Pan TM, Han JW, Quan C, Sun LD, Zheng HF, Zuo XB, Xu SX, Sheng YJ, Yao S, Hu WL, Li Y, Yu ZY, Yin XY, Zhang XJ, Cui Y, Yang S. TNIP1, SLC15A4, ETS1, RasGRP3 and IKZF1 are associated with clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus in a Chinese Han population. Lupus. 2010;19:1181–1186. doi: 10.1177/0961203310367918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang W, Shen N, Ye DQ, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Qian XX, Hirankarn N, Ying D, Pan HF, Mok CC, Chan TM, Wong RW, Lee KW, Mok MY, Wong SN, Leung AM, Li XP, Avihingsanon Y, Wong CM, Lee TL, Ho MH, Lee PP, Chang YK, Li PH, Li RJ, Zhang L, Wong WH, Ng IO, Lau CS, Sham PC, Lau YL. Genome-wide association study in Asian populations identifies variants in ETS1 and WDFY4 associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong H, Li XL, Li M, Hao LX, Chen RW, Xiang K, Qi XB, Ma RZ, Su B. Replicated associations of TNFAIP3, TNIP1 and ETS1 with systemic lupus erythematosus in a southwestern Chinese population. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R186. doi: 10.1186/ar3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang C, Ahlford A, Jarvinen TM, Nordmark G, Eloranta ML, Gunnarsson I, Svenungsson E, Padyukov L, Sturfelt G, Jonsen A, Bengtsson AA, Truedsson L, Eriksson C, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Sjowall C, Julkunen H, Criswell LA, Graham RR, Behrens TW, Kere J, Ronnblom L, Syvanen AC, Sandling JK. Genes identified in Asian SLE GWASs are also associated with SLE in Caucasian populations. European journal of human genetics: EJHG. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatzikyriakidou A, Voulgari PV, Georgiou I, Drosos AA. Altered sequence of the ETS1 transcription factor may predispose to rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology. 2013;42:11–14. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2012.711367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okada Y, Terao C, Ikari K, Kochi Y, Ohmura K, Suzuki A, Kawaguchi T, Stahl EA, Kurreeman FA, Nishida N, Ohmiya H, Myouzen K, Takahashi M, Sawada T, Nishioka Y, Yukioka M, Matsubara T, Wakitani S, Teshima R, Tohma S, Takasugi K, Shimada K, Murasawa A, Honjo S, Matsuo K, Tanaka H, Tajima K, Suzuki T, Iwamoto T, Kawamura Y, Tanii H, Okazaki Y, Sasaki T, Gregersen PK, Padyukov L, Worthington J, Siminovitch KA, Lathrop M, Taniguchi A, Takahashi A, Tokunaga K, Kubo M, Nakamura Y, Kamatani N, Mimori T, Plenge RM, Yamanaka H, Momohara S, Yamada R, Matsuda F, Yamamoto K. Meta-analysis identifies nine new loci associated with rheumatoid arthritis in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2012;44:511–516. doi: 10.1038/ng.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Knight J, Ellinghaus E, Stuart PE, Capon F, Ding J, Li Y, Tejasvi T, Gudjonsson JE, Kang HM, Allen MH, McManus R, Novelli G, Samuelsson L, Schalkwijk J, Stahle M, Burden AD, Smith CH, Cork MJ, Estivill X, Bowcock AM, Krueger GG, Weger W, Worthington J, Tazi-Ahnini R, Nestle FO, Hayday A, Hoffmann P, Winkelmann J, Wijmenga C, Langford C, Edkins S, Andrews R, Blackburn H, Strange A, Band G, Pearson RD, Vukcevic D, Spencer CC, Deloukas P, Mrowietz U, Schreiber S, Weidinger S, Koks S, Kingo K, Esko T, Metspalu A, Lim HW, Voorhees JJ, Weichenthal M, Wichmann HE, Chandran V, Rosen CF, Rahman P, Gladman DD, Griffiths CE, Reis A, Kere J, Duffin KC, Helms C, Goldgar D, Li Y, Paschall J, Malloy MJ, Pullinger CR, Kane JP, Gardner J, Perlmutter A, Miner A, Feng BJ, Hiremagalore R, Ike RW, Christophers E, Henseler T, Ruether A, Schrodi SJ, Prahalad S, Guthery SL, Fischer J, Liao W, Kwok P, Menter A, Lathrop GM, Wise C, Begovich AB, Onoufriadis A, Weale ME, Hofer A, Salmhofer W, Wolf P, Kainu K, Saarialho-Kere U, Suomela S, Badorf P, Huffmeier U, Kurrat W, Kuster W, Lascorz J, Mossner R, Schurmeier-Horst F, Stander M, Traupe H, Bergboer JG, Heijer MD, van de Kerkhof PC, Zeeuwen PL, Barnes L, Campbell LE, Cusack C, Coleman C, Conroy J, Ennis S, Fitzgerald O, Gallagher P, Irvine AD, Kirby B, Markham T, McLean WH, McPartlin J, Rogers SF, Ryan AW, Zawirska A, Giardina E, Lepre T, Perricone C, Martin-Ezquerra G, Pujol RM, Riveira-Munoz E, Inerot A, Naluai AT, Mallbris L, Wolk K, Leman J, Barton A, Warren RB, Young HS, Ricano-Ponce I, Trynka G, Pellett FJ, Henschel A, Aurand M, Bebo B, Gieger C, Illig T, Moebus S, Jockel KH, Erbel R, Donnelly P, Peltonen L, Blackwell JM, Bramon E, Brown MA, Casas JP, Corvin A, Craddock N, Duncanson A, Jankowski J, Markus HS, Mathew CG, McCarthy MI, Palmer CN, Plomin R, Rautanen A, Sawcer SJ, Samani N, Viswanathan AC, Wood NW, Bellenguez C, Freeman C, Hellenthal G, Giannoulatou E, Pirinen M, Su Z, Hunt SE, Gwilliam R, Bumpstead SJ, Dronov S, Gillman M, Gray E, Hammond N, Jayakumar A, McCann OT, Liddle J, Perez ML, Potter SC, Ravindrarajah R, Ricketts M, Waller M, Weston P, Widaa S, Whittaker P, Nair RP, Franke A, Barker JN, Abecasis GR, Elder JT, Trembath RC. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ng.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shan S, Dang J, Li J, Yang Z, Zhao H, Xin Q, Ma X, Liu Y, Bian X, Gong Y, Liu Q. ETS1 variants confer susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis in Han Chinese. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R87. doi: 10.1186/ar4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei L, Zhou Q, Hou S, Bai L, Liu Y, Qi J, Xiang Q, Zhou Y, Kijlstra A, Yang P. MicroRNA-146a and Ets-1 gene polymorphisms are associated with pediatric uveitis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubois PC, Trynka G, Franke L, Hunt KA, Romanos J, Curtotti A, Zhernakova A, Heap GA, Adany R, Aromaa A, Bardella MT, van den Berg LH, Bockett NA, de la Concha EG, Dema B, Fehrmann RS, Fernandez-Arquero M, Fiatal S, Grandone E, Green PM, Groen HJ, Gwilliam R, Houwen RH, Hunt SE, Kaukinen K, Kelleher D, Korponay-Szabo I, Kurppa K, Macmathuna P, Maki M, Mazzilli MC, McCann OT, Mearin ML, Mein CA, Mirza MM, Mistry V, Mora B, Morley KI, Mulder CJ, Murray JA, Nunez C, Oosterom E, Ophoff RA, Polanco I, Peltonen L, Platteel M, Rybak A, Salomaa V, Schweizer JJ, Sperandeo MP, Tack GJ, Turner G, Veldink JH, Verbeek WH, Weersma RK, Wolters VM, Urcelay E, Cukrowska B, Greco L, Neuhausen SL, McManus R, Barisani D, Deloukas P, Barrett JC, Saavalainen P, Wijmenga C, van Heel DA. Multiple common variants for celiac disease influencing immune gene expression. Nat Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ng.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Sun LD, Lu WS, Hu WL, Gao JP, Cheng YL, Yu ZY, Yao S, He CF, Liu JL, Cui Y, Yang S. Expression analysis of ETS1 gene in peripheral blood mononuclear cells with systemic lupus erythematosus by real-time reverse transcription PCR. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:2287–2288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du C, Liu C, Kang J, Zhao G, Ye Z, Huang S, Li Z, Wu Z, Pei G. MicroRNA miR-326 regulates T(H)-17 differentiation and is associated with the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1252–1259. doi: 10.1038/ni.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.John SA, Clements JL, Russell LM, Garrett-Sinha LA. Ets-1 regulates plasma cell differentiation by interfering with the activity of the transcription factor Blimp-1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:951–962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo W, Mayeux J, Guttierez T, Russell LM, Getahun A, Muller J, Tedder TF, Parnes J, Rickert RC, Nitschke L, Cambier J, Satterthwaite AB, Garrett-Sinha LA. A balance between BCR and inhibitory receptor signaling controls plasma cell differentiation by maintaining optimal Ets1 levels. J Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400666. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.John S, Russell L, Chin SS, Luo W, Oshima R, Garrett-Sinha LA. Transcription factor ets1, but not the closely related factor ets2, inhibits antibody-secreting cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:522–532. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00612-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muthusamy N, Barton K, Leiden JM. Defective activation and survival of T cells lacking the Ets-1 transcription factor. Nature. 1995;377:639–642. doi: 10.1038/377639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eyquem S, Chemin K, Fasseu M, Bories JC. The Ets-1 transcription factor is required for complete pre-T cell receptor function and allelic exclusion at the T cell receptor {beta} locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15712–15717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405546101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prak EL, Weigert M. Light chain replacement: a new model for antibody gene rearrangement. J Exp Med. 1995;182:541–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eyquem S, Chemin K, Fasseu M, Chopin M, Sigaux F, Cumano A, Bories JC. The development of early and mature B cells is impaired in mice deficient for the Ets-1 transcription factor. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3187–3196. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cooke MP, Heath AW, Shokat KM, Zeng Y, Finkelman FD, Linsley PS, Howard M, Goodnow CC. Immunoglobulin signal transduction guides the specificity of B cell-T cell interactions and is blocked in tolerant self-reactive B cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:425–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fulcher DA, Lyons AB, Korn SL, Cook MC, Koleda C, Parish C, Fazekas de St Groth B, Basten A. The fate of self-reactive B cells depends primarily on the degree of antigen receptor engagement and availability of T cell help. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2313–2328. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt KN, Cyster JG. Follicular exclusion and rapid elimination of hen egg lysozyme autoantigen-binding B cells are dependent on competitor B cells, but not on T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:284–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cyster JG, Goodnow CC. Antigen-induced exclusion from follicles and anergy are separate and complementary processes that influence peripheral B cell fate. Immunity. 1995;3:691–701. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Healy JI, Dolmetsch RE, Timmerman LA, Cyster JG, Thomas ML, Crabtree GR, Lewis RS, Goodnow CC. Different nuclear signals are activated by the B cell receptor during positive versus negative signaling. Immunity. 1997;6:419–428. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodnow CC, Sprent J, Fazekas de St Groth B, Vinuesa CG. Cellular and genetic mechanisms of self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435:590–597. doi: 10.1038/nature03724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.William J, Euler C, Christensen S, Shlomchik MJ. Evolution of autoantibody responses via somatic hypermutation outside of germinal centers. Science. 2002;297:2066–2070. doi: 10.1126/science.1073924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.William J, Euler C, Shlomchik MJ. Short-lived plasmablasts dominate the early spontaneous rheumatoid factor response: differentiation pathways, hypermutating cell types, and affinity maturation outside the germinal center. J Immunol. 2005;174:6879–6887. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sweet RA, Christensen SR, Harris ML, Shupe J, Sutherland JL, Shlomchik MJ. A new site-directed transgenic rheumatoid factor mouse model demonstrates extrafollicular class switch and plasmablast formation. Autoimmunity. 2010;43:607–618. doi: 10.3109/08916930903567500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giltiay NV, Lu Y, Cullen JL, Jorgensen TN, Shlomchik MJ, Li X. Spontaneous loss of tolerance of autoreactive B cells in Act1-deficient rheumatoid factor transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2013;191:2155–2163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sang A, Niu H, Cullen J, Choi SC, Zheng YY, Wang H, Shlomchik MJ, Morel L. Activation of rheumatoid factor-specific B cells is antigen dependent and occurs preferentially outside of germinal centers in the lupus-prone NZM2410 mouse model. J Immunol. 2014;193:1609–1621. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rathmell JC, Goodnow CC. Effects of the lpr mutation on elimination and inactivation of self-reactive B cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:2831–2842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Enders A, Bouillet P, Puthalakath H, Xu Y, Tarlinton DM, Strasser A. Loss of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim inhibits BCR stimulation-induced apoptosis and deletion of autoreactive B cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1119–1126. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fang W, Weintraub BC, Dunlap B, Garside P, Pape KA, Jenkins MK, Goodnow CC, Mueller DL, Behrens TW. Self-reactive B lymphocytes overexpressing Bcl-xL escape negative selection and are tolerized by clonal anergy and receptor editing. Immunity. 1998;9:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang NH, Cheung YH, Loh C, Pau E, Roy V, Cai YC, Wither J. B cell activating factor (BAFF) and T cells cooperate to breach B cell tolerance in lupus-prone New Zealand Black (NZB) mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cyster JG, Goodnow CC. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1C negatively regulates antigen receptor signaling in B lymphocytes and determines thresholds for negative selection. Immunity. 1995;2:13–24. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cornall RJ, Cyster JG, Hibbs ML, Dunn AR, Otipoby KL, Clark EA, Goodnow CC. Polygenic autoimmune traits: Lyn, CD22, and SHP-1 are limiting elements of a biochemical pathway regulating BCR signaling and selection. Immunity. 1998;8:497–508. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang H, Shlomchik MJ. Autoantigen-specific B cell activation in Fas-deficient rheumatoid factor immunoglobulin transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:639–649. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.