Abstract

Purpose:

To compare the clinical outcomes of deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) for keratoconus in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) versus those without VKC.

Methods:

In this retrospective comparative study, records of 262 eyes with keratoconus (Group 1) and 28 keratoconic eyes with VKC (Group 2) that had undergone DALK were compiled. Reviewed parameters included length of follow-up, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), refractive error, complications and cumulative graft survival.

Results:

Mean duration of follow-up was 38.6 ± 20.2 and 34.4 ± 20.9 months in groups 1 and 2, respectively (P = 0.21). Mean post-operative BCVA was 0.19 ± 0.11 and 0.20 ± 0.15 logMAR, in groups 1 and 2 (P = 0.79). BCVA≥20/40 was achieved in 91.6 and 88.5% of eyes in groups 1 and 2, respectively (P = 0.48). Epithelial problems were encountered in 31.3 and 42.9% of operated eyes, respectively (P = 0.16). Vascularization of suture tracts and stitch abscesses were encountered more frequently in the eyes with VKC (P = 0.01 and <0.001, respectively). At the 33-month follow-up examination, rejection-free graft survival rates were 56.0% in group 1 and 33.3% in group 2, with mean durations of 41.0 and 32.1 months, respectively (P = 0.15). Graft survival rates were 98.1% in group 1 and 95.0% in group 2, with mean durations of 88.6 and 88.4 months, respectively (P = 0.74).

Conclusion:

Clinical outcomes of DALK in keratoconic eyes with VKC were comparable to those in eyes with keratoconus alone. However, complications such as suture tract vascularization and stitch abscesses were more common when VKC coexisted, necessitating closer monitoring.

Keywords: Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty, Graft Survival, Keratoconus, Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

INTRODUCTION

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a chronic allergic conjunctivitis that may be associated with keratoconus.[1,2] Abnormal corneal topographic patterns favoring a diagnosis of keratoconus have been reported in 26.8% of VKC cases.[3] Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) is now the treatment of choice for keratoconus when other less invasive options such as rigid gas permeable contact lens fitting and intrastromal corneal ring implantation are not appropriate.[4] It is well recognized that excellent visual outcomes and graft survival can be obtained following DALK for this indication.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10] However, there are theoretical concerns that the prognosis might be worse in eyes with keratoconus and concomitant VKC because of several factors such as chronic inflammation, ocular surface abnormalities and peripheral corneal vascularization.

Previously, no significant differences were found in visual outcomes or graft survival rates after penetrating keratoplasty (PK) for keratoconus in eyes with or without a history of VKC.[11,12,13] Wagoner et al found that graft survival rates, post-operative complications and visual outcomes are comparable after PK for keratoconus in eyes with or without VKC.[11] Egrilmez et al evaluated the effect of VKC on the clinical outcomes of PK in eyes with keratoconus.[12] They found that outcomes of PK in keratoconic eyes with VKC were comparable to eyes with keratoconus alone. However, complications such as loose sutures and steroid-induced cataracts were more common in cases with co-existing VKC. Thomas et al compared the prevalence of endothelial rejection episodes and the probability of graft survival after initial and repeat PK in keratoconic patients with and without atopy and found no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of endothelial graft rejection episodes or the probability of graft survival.[13]

Although, good visual results and low complication rates were reported following DALK for keratoconus in several studies;[4,5,6,7,8,9,10] these reports did not differentiate or specify whether keratoconus was associated with VKC, and to the best of our knowledge, the outcome of DALK in eyes with keratoconus and concomitant VKC has not been well documented. In the present study, a consecutive series of DALK procedures performed for keratoconus over a 9-year period in eyes with or without VKC was retrospectively reviewed to compare the outcomes, complications and graft survival rates.

METHODS

In this retrospective comparative interventional case series, records of consecutive keratoconic patients who underwent DALK from October 2004 to June 2012 were compiled. Reviewed parameters included age, sex, history of VKC, length of post-operative follow-up, pre- and post-operative best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and refraction, timing and number of graft rejection episodes, complications i.e., epithelial problems, suture-related complications, high intraocular pressure (IOP) and cataracts, secondary surgical interventions, and final graft clarity.

Inclusion criteria consisted of moderate (mean keratometric values between 47 and 52 D) to advanced keratoconus (mean keratometric values >52 D or immeasurable by keratometry) with poor spectacle corrected visual acuity, rigid gas permeable (RGP) contact lens intolerance, or inappropriate contact lens fit. The inclusion criteria also required a minimum follow-up time of 12 months.

Exclusion criteria included co-existing ocular pathologies, such as cataracts, retinal disorders or glaucoma. Data for patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded from the analysis. Approval to use the patients’ data was received from the institutional review board (IRB).

Preoperatively, keratoconus was diagnosed based on the slit lamp findings (corneal ectasia, stromal thinning, Fleischer's ring and Vogt's striae) and keratometry, and confirmed using conventional corneal topography (TMS-1 Topographic Modeling System, version 1.61, Computed Anatomy Inc., New York, USA). Preoperative evaluations included a complete ophthalmologic examination, encompassing measurement of uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), manifest refraction (if possible), BCVA with fully corrective glasses or with a RGP lens using the Snellen acuity chart, slit lamp biomicroscopy, tonometry, dilated fundus examination and conventional corneal topography.

A diagnosis of VKC was made if the patients presented during the active phase of the disease complaining of severe itching together with characteristic signs, including giant papillae on the upper palpebral conjunctiva, limbal gelatinous infiltrates and Horner-Trantas dots (15 cases), or had a history of treatment for VKC with suggestive residual findings such as pseudogerontoxon (13 cases). Active VKC was brought under control preoperatively using topical short-term pulsed steroids, with cromolyn sodium 4% drops four times a day and ketotifen drops twice a day. After discontinuation of the topical steroids, all the patients were maintained chronically using a topical mast cell stabilizer and antihistamine throughout hot seasons of the year. In this group, surgery was deferred until the cold seasons when the disease became inactive. Thus, all the patients were symptom-free at least 6 months before surgery.

Post-operative outcomes included UCVA, BCVA, manifest refraction, mean keratometric readings and keratometric astigmatism. Additionally, intra-and postoperative complications, episodes of graft-rejection reaction, graft transparency and further surgical interventions (if needed) were noted.

Surgical Technique

All patients were operated under general anesthesia by a single experienced anterior segment surgeon (MAJ) using the same surgical technique and postoperative medication regimens. DALK was performed using the big-bubble technique previously described in detail.[4] For cases in which big-bubble formation could not be accomplished after several attempts, manual stromal dissection down to Descemet's membrane (DM) was progressively performed using a crescent knife attempting to remove as much corneal stroma as possible. The diameter of recipient trephination was chosen based on vertical corneal diameter (VCD), as follows: A 7.75-mm recipient trephine was used for VCD of <10.5 mm and an 8-mm trephine was employed for VCD of ≥10.5 mm. Donor tissues, free of DM and endothelium, and oversized by 0.25 mm, were punched out from the endothelial side using a Barron donor punch (Katena, Denville, NJ, USA). The suturing technique involved a 16-bite interrupted suture, a single running suture with 16–18 bites, or combined sutures (8-bite interrupted accompanied by 16-bite single running). The suture material was the same in all eyes and with all techniques (10/0 Nylon, Sharpoint, Angiotech, Vancouver, Canada). In group 2, the interrupted suturing technique was chosen when there was significant peripheral vascularization. During suturing, an attempt was made to incorporate approximately 90% of the thickness of the recipient and donor tissues. Intraoperative keratoscopy was performed to adjust the suture tension.

Post-operative Course

Postoperatively, daily evaluation was performed until re-epithelialization was complete. Thereafter, follow-up examinations were performed at 7 and 30 days; 3, 6 and 12 months; at least 3 months after complete suture removal, and every 6 months thereafter. Postoperatively, all patients received topical chloramphenicol drops every 6 hours for 30 days and topical betamethasone 0.1% every 6 hours tapered over 4 to 6 months according to the level of inflammation. If indicated, topical hypertonic sodium chloride 5% was prescribed to reduce graft edema and topical lubricants were added to hasten epithelial healing. In cases of epithelial instability or persistent epithelial defects, a bandage contact lens (OmniFlex, Hydron, UK) and/or temporary tarsorrhaphy were applied. In the event of VKC reactivation, the same preoperative topical treatment regimen was resumed. Acute graft rejection reaction was defined as the presence of subepithelial infiltration (subepithelial graft rejection) or stromal edema and infiltration with or without interface vascularization (stromal graft rejection) or a combination thereof (mixed). Acute rejection reactions of the corneal transplants were treated by frequent application of topical betamethasone 0.1% eye drops.

Postoperatively, keratometric astigmatism was reduced by selective interrupted suture removal starting at the third month with adjustment of the continuous suture tension. Selective interrupted suture removal was performed sequentially starting with the tight sutures (determined by keratometric readings) and continued until an acceptable amount of astigmatism was achieved. Thereafter, the remaining sutures were left in place unless there was a suture-related complication, such as an abscess, loosening, or suture-tract vascularization.

Graft failure was defined as the irreversible loss of central graft clarity, significant interface vascularization and haziness, or need for repeat keratoplasty for any reason, such as graft opacity, interface haziness, significant interface wrinkling, recurrence of keratoconus and an unacceptable level of keratometric astigmatism. The time of graft failure was defined as the visit at which irreversible loss of graft clarity was first documented or when a repeat keratoplasty was performed.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, MI, USA). Based on the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test and Q-Q plotting, Student's t-test and Mann-Whitney test were used to compare normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively. The Fischer exact test and χ2-test were used for comparison of qualitative parameters. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank test were used to evaluate and compare the cumulative incidence of rejection-free graft survival, as well as the rate of graft survival in the two study groups. P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

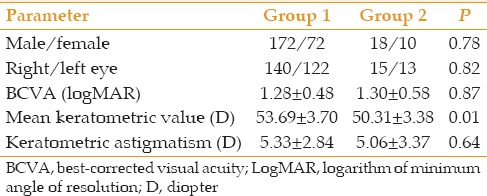

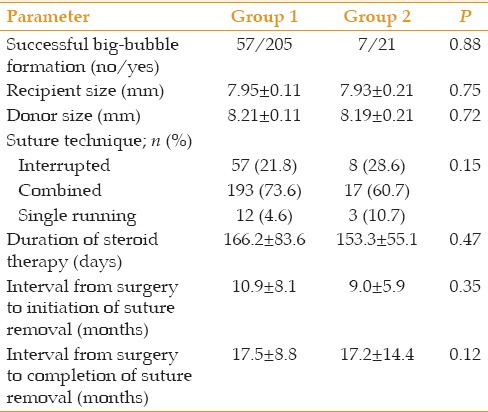

A total of 290 consecutive eyes (including 152 right eyes) of 272 patients (including 190 male subjects) with keratoconus were operated during the study period. Overall, 262 (90.3%) eyes had keratoconus only (Group 1), whereas a history of VKC existed for 28 (9.7%) eyes (Group 2). Mean patient age was 27.8 ± 8.2 (range, 14 to 52) years in group 1 and 27.2 ± 6.8 (range, 15 to 41) years in group 2 (P = 0.71). Demographic data and pre- and operative details are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Preoperatively, eight eyes from group 2 had significant peripheral corneal vascularization. Giant papillary reaction of the conjunctiva was not encountered in any participants.

Table 1.

Demographic and preoperative details

Table 2.

Data relevant to the surgery and the postoperative course

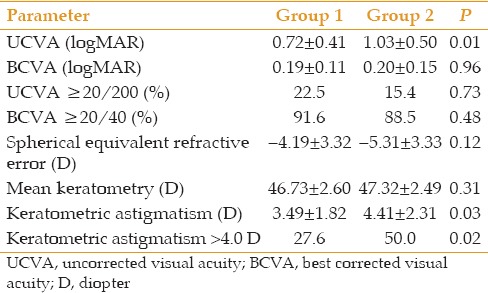

Mean duration of follow-up was 38.6 ± 20.2 months in group 1 and 34.4 ± 20.9 months in group 2 (P = 0.21). Table 3 compares the visual and refractive outcomes at final follow-up between the study groups. As indicated, mean post-operative UCVA was significantly better in group 1 which is best explained by significantly lower post-operative keratometric astigmatism. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of post-operative BCVA, spherical equivalent refractive error, or mean keratometric value [Table 3].

Table 3.

Visual and refractive outcomes at final follow-up examination

To reduce postoperative refractive error, a secondary surgical intervention, including a relaxing incision, photorefractive keratectomy/LASIK, or phakic intraocular lens implantation was performed in 80 (30.5%) of the eyes in group 1 and six (21.4%) eyes in group 2 (P = 0.39).

Complications

Epithelial defects improved after 3.0 ± 1.8 days in group 1 and after 3.6 ± 2.2 days in group 2 (P = 0.20). Epithelial problems, such as persistent epithelial defects (1.1% versus 3.8%), filamentary keratitis (2.6% versus 5.8%) and superficial punctate keratitis (27.6% versus 33.3%), which required bandage contact lens fitting or blepharorrhaphy were encountered in 82 (31.3%) eyes in group 1 and 12 (42.9%) eyes in group 2, respectively (P = 0.16).

Suture complications were observed in 171 (65.3%) of eyes in group 1 and 22 (78.6%) of the eyes in group 2. These complications included prematurely loose or broken sutures (58.4% versus 50.0%, P = 0.12), suture-tract vascularization (13.0 versus 32.1%, P = 0.01) and stitch-associated abscesses (17.9% versus 53.6%, P < 0.001) in groups 1 and 2, respectively.

IOP > 21 mmHg was observed in 34 (13.0%) eyes in group 1 and three (10.3%) eyes in group 2 during follow-up (P > 0.99); all cases were controlled medically. Some degree of lens opacity developed in 37 (14.1%) eyes in group 1 and 7 (25.0%) eyes in group 2 (P = 0.15).

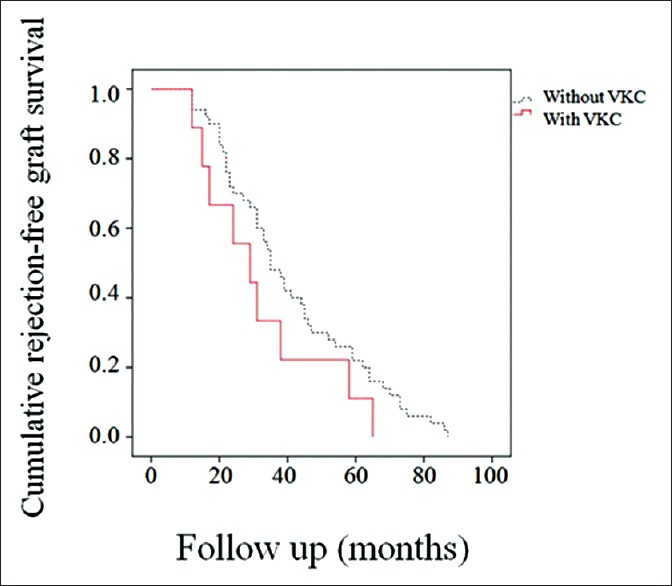

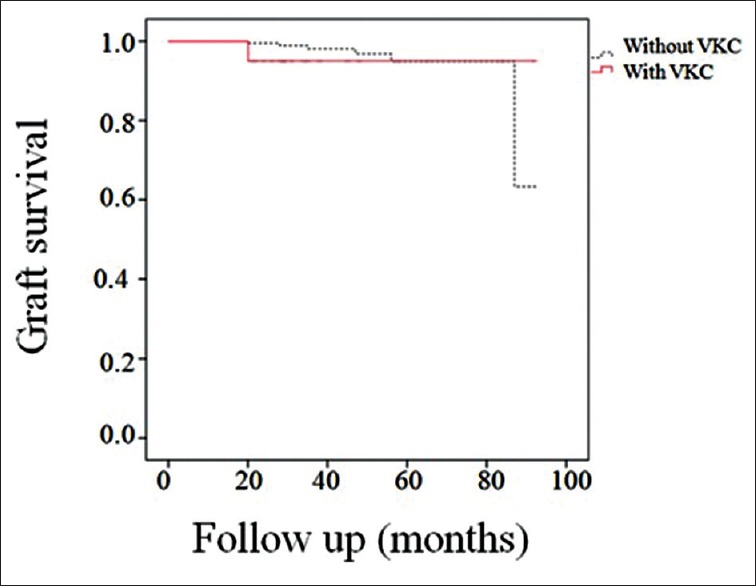

Seven eyes in group 2 experienced recurrence of VKC during the follow-up period. Overall, 53 (20.2%) eyes in group 1 and ten (35.7%) eyes in group 2 experienced at least one episode of graft rejection (P = 0.09). Eleven (4.2%) eyes in group 1 and three (10.7%) eyes in group 2 experienced two or more episodes of graft rejection (P = 0.02). The total episodes of subepithelial, stromal and mixed graft rejection were 62 versus 10, 9 versus 4, and 6 versus 3 in groups 1 and 2, respectively. At 33 months (median follow-up), the rejection-free graft survival rates were 56.0% in group 1 and 33.3% in group 2, with mean durations of 41.0 (95% confidence interval [CI]; 35.2 to 46.9) months and 32.1 (95% CI; 19.9 to 44.3) months, respectively (P = 0.15; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Thirty-three months after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, the rejection-free graft survival rates were 56.0% in group 1 and 33.3% in group 2.

At the final follow-up examination, 257 (98.1%) eyes in group 1 and 27 eyes (96.4%) in group 2 remained clear (P = 0.46). The causes of graft opacity were stromal graft rejection (n = 1) and interface vascularization (n = 4) in group 1 and persistent epithelial defects (n = 1) in group 2. Repeat keratoplasty was performed in six eyes in group 1 due to recurrent keratoconus (n = 3), interface wrinkling (n = 1), stromal graft rejection (n = 1), or delayed DM detachment after phakic intraocular lens implantation (n = 1). Repeat keratoplasty was performed in one eye in group 2 that suffered from persistent epithelial defects. Considering graft opacity and the need for repeat keratoplasty as graft failure, the cumulative graft survival rate was 98.1% in group 1 and 95.0% in group 2 at 33 months (median follow-up), with mean durations of 88.6 (95% CI; 84.9 to 92.3) months and 88.4 (95% CI; 81.5 to 95.3) months, respectively (P = 0.74, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Thirty-three months after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, the graft survival rates were 98.1% in group 1 and 95.0% in group 2.

As mentioned earlier, there were two subgroups of VKC patients; one with active VKC which had been controlled before surgery and the other group which only had history of treatment for VKC. Comparison between these two subgroups did not yield any significant difference in terms of visual and refractive outcomes as well as, post-operative complications.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a consecutive series of DALK procedures performed over a 9-year period in keratoconic eyes with or without VKC was retrospectively reviewed to identify differences in visual outcomes, postoperative complications and graft survival rates. The two study groups were balanced in terms of preoperative BCVA and keratometric astigmatism, age at the time of keratoplasty, donor and recipient trephination size and suturing technique. However, mean preoperative keratometric values were flatter in eyes with VKC as compared to those without VKC, which indicates that patients with keratoconus and concomitant VKC tended to be operated earlier due to poor contact lens tolerance caused by ocular discomfort. On the other hand, it has been reported that keratoconus with VKC progresses more rapidly, resulting in severe corneal thinning and bulging as well as more frequent corneal hydrops[14,15] and thus these patients towards may have been shifted toward PK, leaving less severe cases for DALK.

The results of the current study indicate that an excellent visual outcome can be expected following DALK in eyes with VKC. The percentage of eyes attaining final BCVA of 20/40 or better was 88.5% which is comparable to results in eyes with only keratoconus (91.6%). This result is better than that described by other investigators who reported BCVA of≥20/40 in 57.1%,[14] 68.8%[15] and 76.2%[11] of VKC patients following PK.

The amount of spherical equivalent refractive error and the mean keratometric value did not differ between the study groups in the current series. However, a significantly larger amount of keratometric astigmatism was observed in the VKC group. Although, both study groups had a comparable interval from the time of the operation to initial and complete suture removal, suture complications, including peripheral vascularization and abscess formation were more commonly observed in the VKC group, which could lead to uneven wound healing and hence, higher corneal astigmatism.

Complications were also evaluated and compared in the present study. Concerns that eyes with VKC may be more prone to ocular surface related complications were not confirmed by the results of the current study, which demonstrated that the rate of epithelial defect improvement and the prevalence of epithelial problems were comparable to those observed in the eyes with only keratoconus. Ocular surface-related complications resulted only in one case of graft failure in an eye with VKC and no graft failure in eyes of the other group. The fact that all eyes with VKC underwent DALK only after good medical control of the surface inflammation and that the epithelial problems were appropriately managed after surgery may be the explanation for these results.

Post-operatively, the same duration of topical corticosteroid therapy was used in the eyes with and without VKC, which means that patients with VKC could be tapered off the topical corticosteroids as easily as counterparts without VKC. Consequently, despite concerns that eyes with VKC had a higher risk of developing cataract and glaucoma because of the greater lifetime cumulative dose of topical corticosteroids, the rate of these complications did not differ between the study groups, and all of the cases of high IOP were successfully managed with anti-glaucoma medications.

There are theoretical concerns that the rate of graft rejection might be higher in eyes with keratoconus and concomitant VKC because of several confounding factors, such as chronic inflammation, ocular surface abnormalities and peripheral corneal vascularization. Although, DALK eliminates the risk of endothelial rejection, other types of rejection (subepithelial and stromal) that can lead to graft failure may still occur.[16,17] In the present study, eyes with VKC more commonly developed a first episode of rejection, although the difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, the two study groups were balanced for the mean time from surgery to the first episode of graft rejection. This finding is attributable to the fact that all eyes with VKC underwent DALK only after good medical control of the surface inflammation. However, the rate of second or more graft rejection episodes was significantly higher in the VKC group. One possible explanation for this finding could be the higher prevalence of suture tract neovascularization in this group. Additionally, after keratoplasty, these patients could experience exacerbation of ocular inflammation during the hot seasons, which could facilitate the episodes of graft rejection.[18] Timely diagnosis and frequent topical steroids reversed graft rejection in the VKC group and all subjects regained their levels of visual acuity just before the rejection episode. However, one eye in the keratoconus group was lost to stromal graft rejection.

In the present study, the graft survival rate after DALK was comparably high in both study groups. The cumulative graft survival rate in the VKC group in our series (95.0%) is similar to the percentage of clear grafts after PK for keratoconus associated with VKC reported by Mahmood and Wagoner (92.2%)[15] and Wagoner et al (97.5%).[11] However, Cameron et al reported a lower rate of clear grafts (80%) after PK for keratoconus with concomitant keratoconjunctivitis.[14] Adequate control of ocular inflammation through the use of a topical mast cell stabilizer and antihistamine agents as well as close follow-up for early detection and control of postoperative complications may have contributed to such outcomes.

In summary, in the current study an excellent visual outcome was obtained after DALK for keratoconus in eyes with or without VKC, with no statistically significant differences between the two groups In terms of BCVA graft survival rates. However, close follow-up is required to avoid complications related to sutures and graft rejection reactions in VKC patients. Our results suggest that DALK can be as effective as, or even better than PK for treating keratoconus with concomitant VKC. A study is now being devised to compare the outcomes of DALK and PK for keratoconus and keratoconjunctivitis to determine the best approach when corneal transplantation is indicated.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khan MD, Kundi N, Saeed N, Gulab A, Nazeer AF. Incidence of keratoconus in spring catarrh. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:41–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabbara KF. Ocular complications of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1999;34:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Totan Y, Hepşen IF, Cekiç O, Gündüz A, Aydin E. Incidence of keratoconus in subjects with vernal keratoconjunctivitis: A videokeratographic study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:824–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feizi S, Javadi MA, Jamali H, Mirbabaee F. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty in patients with keratoconus: Big-bubble technique. Cornea. 2010;29:177–82. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181af25b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funnell CL, Ball J, Noble BA. Comparative cohort study of the outcomes of deep lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Eye. 2006;20:527–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen AW, Goins KM, Sutphin JE, Wandling GR, Wagoner MD. Penetrating keratoplasty versus deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty for the treatment of keratoconus. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:675–81. doi: 10.1007/s10792-010-9393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Söğütlü Sari E, Kubaloğlu A, Ünal M, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty versus deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty: Comparison of optical and visual quality outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:1063–7. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amayem AF, Hamdi IM, Hamdi MM. Refractive and visual outcomes of penetrating keratolasty versus deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty with hydrodissection for treatment of keratoconus. Cornea. 2013;32:e2–5. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31825ca70b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson SL, Ramsay A, Dart JK, Bunce C, Craig E. Comparison of deep lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty in patients with keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javadi MA, Feizi S, Yazdani S, Mirbabaee F. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty versus penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus: A clinical trial. Cornea. 2010;29:365–71. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181b81b71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagoner MD, Ba-Abbad R. King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital Cornea Transplant Study Group. Penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus with or without vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2009;28:14–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31818225dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egrilmez S, Sahin S, Yagci A. The effect of vernal keratoconjunctivitis on clinical outcomes of penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39:772–7. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(04)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas JK, Guel DA, Thomas TS, Cavanagh HD. The role of atopy in corneal graft survival in keratoconus. Cornea. 2011;30:1088–97. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31820d8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron JA, Al-Rajhi AA, Badr IA. Corneal ectasia in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1615–23. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32677-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahmood MA, Wagoner MD. Penetrating keratoplasty in eyes with keratoconus and vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2000;19:468–70. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200007000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson SL, Tuft SJ, Dart JK. Patterns of rejection after deep lamellar keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:556–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams KA, Hornsby NB, Bartlett CM, Holland HK, Esterman A, Coster DJ, editors. Adelaide: Snap Printing; 2004. The Australian Corneal Graft Registry: 2004 Report; pp. 130–140. 175. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flynn TH, Ohbayashi M, Ikeda Y, Ono SJ, Larkin DF. Effect of allergic conjunctival inflammation on the allogeneic response to donor cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4044–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]