Significance

Enzyme catalytic cycles involve conformational changes that limit the usual steady-state catalytic rate to millisecond turnover numbers. Covalent bond changes occur at transition states with femtosecond lifetimes, a factor of 1012 faster than steady-state catalysis. Coupling millisecond and femtosecond events is unlikely. Femtosecond bond vibrational events can be explored by heavy isotope substitution into enzyme proteins. Heavy-enzyme purine nucleoside phosphorylase was used to explore bond vibrational coupling to catalytic site chemistry. Three distinct protein labeling patterns in purine nucleoside phosphorylase gave reduced catalytic site chemistry rates. The pattern establishes coupling between catalytic site bond vibrational modes and barrier crossing in purine nucleoside phosphorylase.

Keywords: heavy enzymes, transition state coupling, femtosecond dynamics, pre–steady-state chemistry, Born–Oppenheimer enzymes

Abstract

Computational chemistry predicts that atomic motions on the femtosecond timescale are coupled to transition-state formation (barrier-crossing) in human purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP). The prediction is experimentally supported by slowed catalytic site chemistry in isotopically labeled PNP (13C, 15N, and 2H). However, other explanations are possible, including altered volume or bond polarization from carbon-deuterium bonds or propagation of the femtosecond bond motions into slower (nanoseconds to milliseconds) motions of the larger protein architecture to alter catalytic site chemistry. We address these possibilities by analysis of chemistry rates in isotope-specific labeled PNPs. Catalytic site chemistry was slowed for both [2H]PNP and [13C, 15N]PNP in proportion to their altered protein masses. Secondary effects emanating from carbon–deuterium bond properties can therefore be eliminated. Heavy-enzyme mass effects were probed for local or global contributions to catalytic site chemistry by generating [15N, 2H]His8-PNP. Of the eight His per subunit, three participate in contacts to the bound reactants and five are remote from the catalytic sites. [15N, 2H]His8-PNP had reduced catalytic site chemistry larger than proportional to the enzymatic mass difference. Altered barrier crossing when only His are heavy supports local catalytic site femtosecond perturbations coupled to transition-state formation. Isotope-specific and amino acid specific labels extend the use of heavy enzyme methods to distinguish global from local isotope effects.

Protein and atomic motions required for enzymatic catalysis involve a broad range of timescales from the millisecond to the femtosecond. Slower (millisecond) motions are involved in conformational changes that occur during substrate binding and product release (1–4), whereas femtosecond motions (promoting vibrations) are proposed by computational studies to be involved in the chemical step of transition-state formation (covalent bond changes) (5–8). The role of fast (femtosecond) enzyme dynamics in the catalytic cycle has remained elusive and controversial due to the experimental challenge of probing femtosecond motions in enzymes. Previous studies from our laboratory and others have reported that isotopic substitution to create heavy enzymes (13C, 15N, and 2H) often slows catalytic site chemistry and, in some cases, alters rate constants for nonchemical steps (9–12). Reduced catalytic site barrier-crossing (the chemical step) in isotopically labeled enzymes supports coupling of local femtosecond motion to transition-state formation and, in some cases, interaction with slower modes (10, 11).

In early heavy-enzyme studies, Silva et al. (9) uniformly labeled the amino acid residues of human purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) with 13C, 15N, and nonexchangeable 2H in an attempt to perturb local bond vibrational modes without altering the electrostatics of the enzyme (the Born–Oppenheimer approximation) (13). Heavy PNP demonstrated unchanged steady-state kinetic parameters, kinetic isotope effects, and transition state structure, but the chemical rate was decreased. Transition path sampling with heavy and light PNPs studied reactive trajectories and predicted that femtosecond vibrational motions are less coupled in the heavy enzyme (14).

PNP (EC 2.4.2.1) catalyzes the reversible phosphorolysis of 6-oxypurine (and 2′-deoxy)-β-d-ribonucleosides to yield (2-deoxy)-α-d-ribose 1-phosphate and the purine base (15) (Fig. 1). Isotopically labeled PNP expressed from 13C and 15N precursors in D2O solvent is 9.9% heavier than natural abundance PNP and shows a heavy enzyme kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of 1.36 (kchem light/kchem heavy) (9). Reduced catalytic site chemistry in heavy PNP was interpreted as slowed femtosecond atomic vibrational modes giving less-efficient coupling to transition-state formation (9, 15) (Fig. 2).

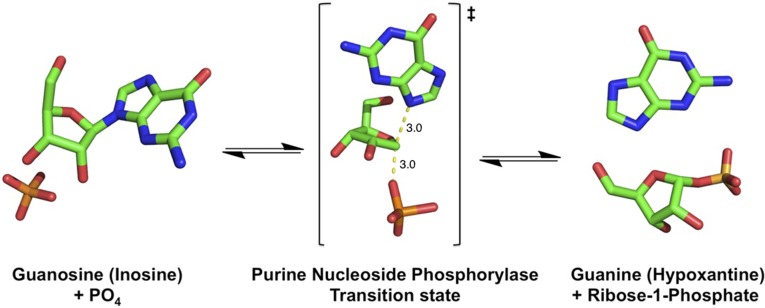

Fig. 1.

Phosphorolysis reaction catalyzed by PNP. Phosphorolysis of 6-oxypurine nucleosides occurs via ribosyl C1 migration from the purine base to the enzyme-stabilized phosphate nucleophile to effect nucleophilic displacement by electrophile migration. The mechanism is SN1-like through a fully formed ribocation transition state. The α-d-Ribose 1-phosphate and the N7-protonated purine base are products.

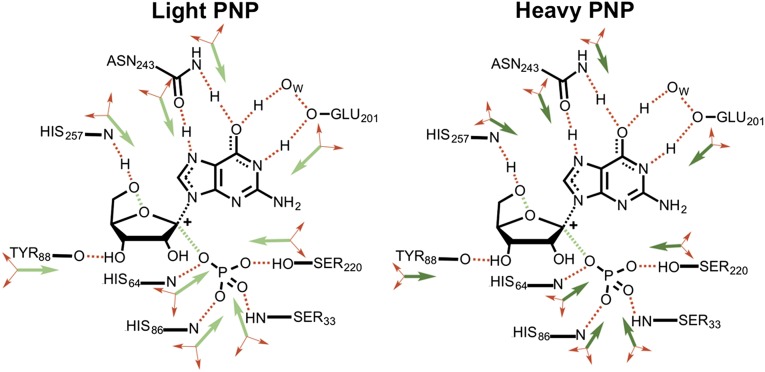

Fig. 2.

Representation of the mass-altered bond vibrational modes in the catalytic site of PNPs. Increased protein atomic mass reduces the frequency of bond vibrations by extension of the relationship where ν, κ , and μ are frequency, force constant, and reduced mass, respectively. The vibrational energy levels are also altered by mass according to , where E, n, and h are energy, quantum number and Planks constant, respectively. The shorter arrows shown for heavy PNP illustrate the altered vibrational frequency. Green arrows promote barrier-crossing, and red arrows are orthogonal to the reaction coordinate. Heavy PNP has a reduced probability of reaching (and crossing) the transition state. Mass-related coupling to barrier crossing is manifested in the experimentally observed decrease in rate of catalytic site chemistry. The diagram is modified from ref. 9.

Outstanding questions not yet resolved for heavy enzyme studies include the following: (i) Is the decrease in catalytic site rate a result of mass-dependent bond frequency changes or an effect of altered bond character from carbon–deuterium bonds replacing carbon–hydrogen bonds? and (ii) Is catalytic site rate reduction a global effect produced by the uniformly labeled enzyme or is it local, a result of altered bond frequencies between active site residues interacting with reactants?

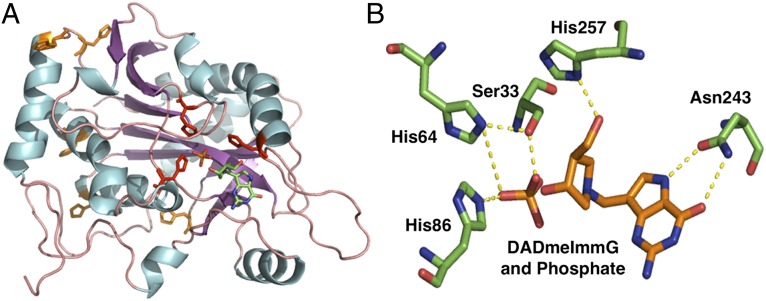

Here we generate three partially labeled PNP enzymes to answer these questions. We made [13C, 15N]-PNP, which is 5.6% heavier, and [2H]PNP, which is 5.4% heavier than natural abundance PNP. These specific labels in PNP test the hypothesis that mass effects and not specific deuterium effects alter the chemical efficiency. We also generated a PNP where all His are substituted by heavy [15N, 2H]His8-PNP to give an enzyme increased by only 0.19% in mass. Human PNP contains eight histidine residues (His20, His23, His64, His86, His104, His135, His230, and His257), three of which (His64, His86, and His257) are located in the active site and in hydrogen bond distance of reactants. The remaining five histidine residues are located in the periphery of the enzyme far away from the active sites (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Location of His residues in PNP. (A) View of a PNP monomer showing the location of the eight histidine residues. Five (orange) are located in the periphery, distal from the active site, and three (red) are located in the active site making direct contact with substrates. (B) Active site of PNP showing His65, His86, and His257 in direct contact with phosphate and the transition state analog DADMe-ImmG (PDB ID code 3PHB).

Both uniformly labeled [13C, 15N]PNP and [2H]PNP showed rate reductions in the chemical step that are proportional to the difference in mass. The result supports mass-dependent atomic mode changes coupled to chemistry and eliminates anomalous deuterium effects. These constructs do not distinguish global dynamic protein changes from the local catalytic site environment.

PNP produced with only [15N, 2H]His labels demonstrates a reduced rate of the chemical step that is larger than expected from mass proportionality. Because three His are in contact with reactants, the result indicates that local bond vibrational modes of the [15N, 2H]His are coupled into the formation of the transition state. Thus, heavy enzyme effects on the chemical step of PNP are local effects involving active site residues in contact with substrates. These results extend and refine the nature of heavy enzyme effects as exemplified by PNP.

Results

Production of Light-, [2H]-, and [13C, 15N]PNPs.

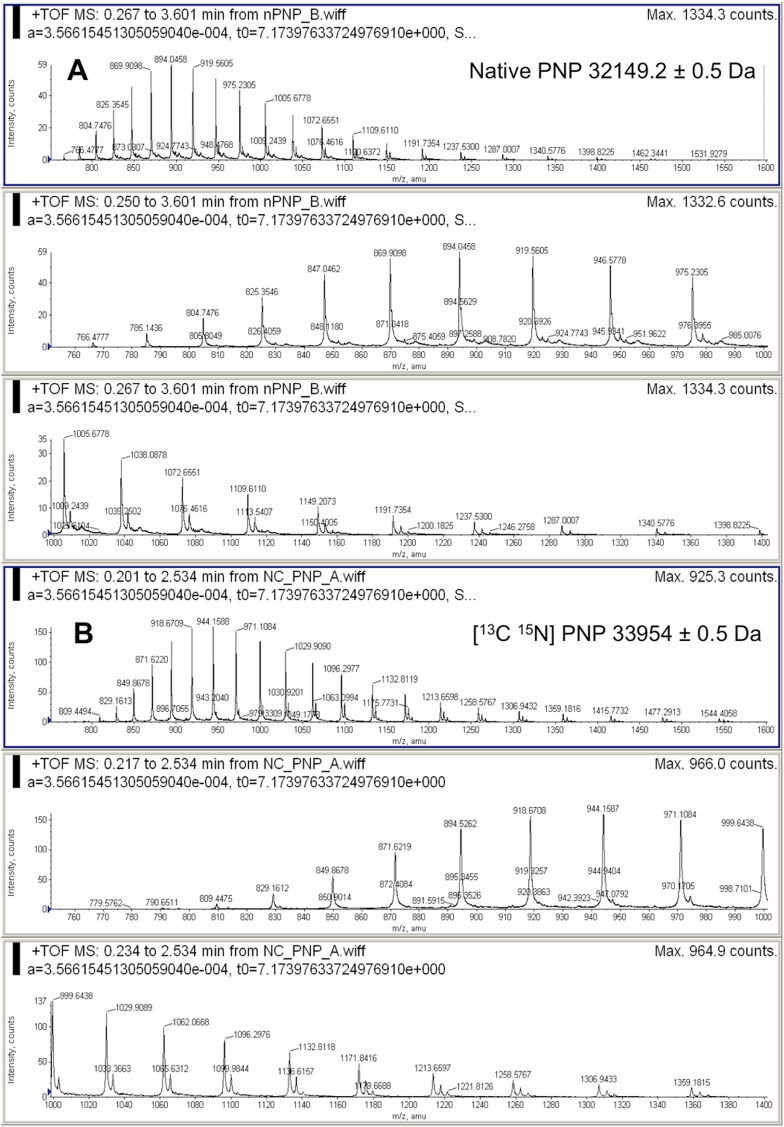

Unlabeled and labeled [13C, 15N]PNP and [2H]PNP were expressed and purified to homogeneity as indicated in Materials and Methods, and their masses by MALDI-TOF-MS were 33,974 Da for [2H]PNP (Fig. S1) and 33,954 for [13C 15N]PNP (Fig. S2). These are 5.3% and 5.6% mass increases, respectively, relative to natural abundance PNP (Materials and Methods). Deuterium substitution is limited to nonexchangeable positions, because solvent-exchangeable positions are exchanged by 1H during purification and storage.

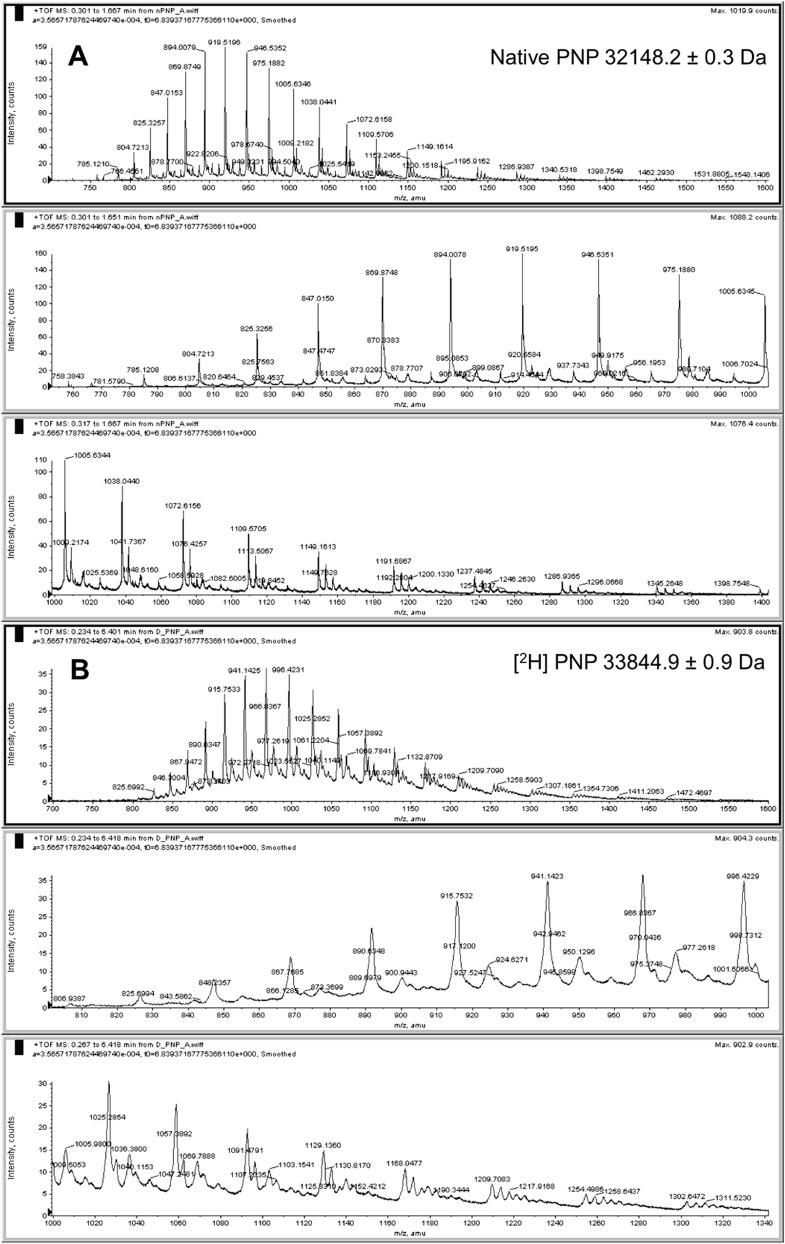

Fig. S1.

Mass analysis of native and deuterium-labeled PNPs. Orbitrap-TOF-MS analysis of native (A) and heavy (B) [2H]PNPs. The masses were 32,148.2 for native PNP and 33,844.9 Da for [2H]PNP to give a 5.3% increase in mass for the labeled enzyme. The error limit is the SD of the masses averaged from the m/z values of individual mass peaks.

Fig. S2.

Orbitrap-TOF-MS analysis of native (A) and heavy (B) [13C, 15N]PNPs. The masses were 32,149.2 for native PNP and 33,954 Da for [13C 15N]PNP to give a 5.6% increase in mass for the labeled enzyme. The error limit is the SD of the masses averaged from the m/z values of individual mass peaks.

Steady-State Kinetics of Light-, [2H]-, and [13C, 15N]PNPs.

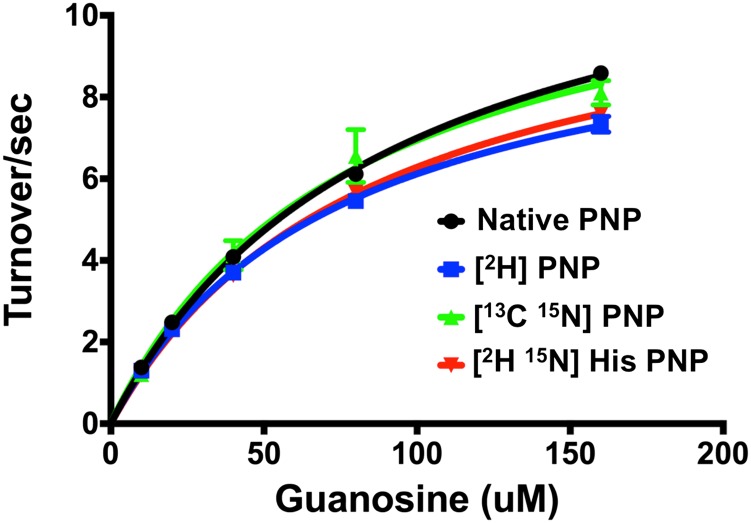

Light and heavy PNPs gave similar Michaelis–Menten kinetic parameters and kcat/Km constants within experimental errors for the phosphorolysis of guanosine (Fig. S3 and Table 1). Thus, the steady-state kinetic constants for guanosine are not substantially altered by isotopic substitutions.

Fig. S3.

Steady-state saturation curves for guanosine phosphorolysis catalyzed by native and heavy [2H]-, [13C, 15N]-, [2H, 15N]8-histidine-PNPs. Heavy and light PNPs showed kinetic parameters within experimental error for the phosphorolysis of guanosine in Michaelis–Menten analysis.

Table 1.

Comparison of the steady state kinetic constants for native [2H]-, [13C, 15N]-, and [2H, 15N]8-His-PNPs

| Kinetic constant | Native | 2H | 13C,15N | 2H, 15N-His |

| kcat, s−1 | 13.4 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ± 0.2 | 12.4 ± 0.9 | 11.6 ± 0.2 |

| Km, μM | 92 ± 4 | 75 ± 3 | 79 ± 11 | 85 ± 3 |

| kcat/Km, M−1⋅s−1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 × 105 | 1.4 ± 0.1 × 105 | 1.6 ± 0.3 × 105 | 1.4 ± 0.1 × 105 |

Catalytic Site Chemistry Rates for Light-, [2H]-, and [13C, 15N]PNPs.

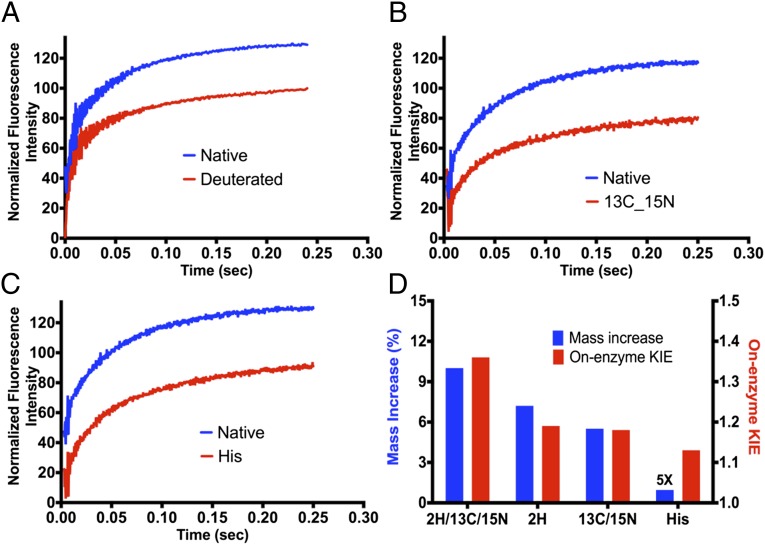

Single-turnover rate constants were measured for light and labeled PNPs in the phosphorolysis of guanosine. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase was in molar excess relative to guanosine to give pseudo first-order rate constants, independent of enzyme concentration. The heavy enzyme KIE values were based on the catalytic site single turnover rates (light kchem/heavy kchem) obtained in stopped-flow studies. The observed KIEs for the labeled enzymes were 1.18 ± 0.03 for [13C, 15N]PNP and 1.19 ± 0.03 for [2H]PNP (Fig. 4). These heavy-enzyme KIE values sum to reflect the enzymatic KIE for fully labeled [2H, 13C, 15N]PNP of 1.36 (9).

Fig. 4.

Representative single-turnover experiments for guanosine phosphorolysis. (A) Native PNP (blue) and [2H]PNP (red). (B) Native PNP (blue) and [13C, 15N]PNP (red). Traces are offset for presentation purposes. (C) Native PNP (blue) vs. 2H-15N-Histidine-PNP (red). Traces are offset for presentation purposes. (D) Comparison of rate differences to mass differences for [2H, 13C, 15N]PNP (data from ref. 9) to those for [2H]PNP, [13C, 15N]PNP, and [2H-15N]His8-PNP (the mass difference of [2H-15N]His8-PNP was multiplied by five to permit visualization).

Production of [15N, 2H]His8-PNP.

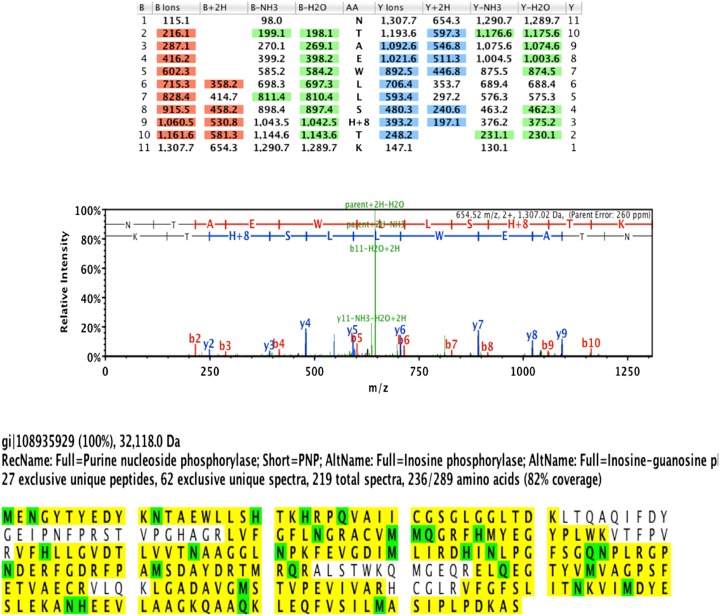

Purine nucleoside phosphorylase was expressed in a His auxotroph of Escherichia coli the presence of [15N, 2H]His and purified. The mass analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS indicated an increase of 62 Da for the labeled enzyme, close to the expected 64 Da increase for incorporation of eight [15N, 2H]His. Nano ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC)-MS/MS analysis of tryptic peptides demonstrated site-specific incorporation for [15N, 2H]His residues and the absence of isotope scrambling into other peptides (Fig. S4).

Fig. S4.

Representative data from nanoUPLC-MS/MS analysis of native and [2H, 15N]8-histidine-PNPs. This analysis established [2H, 15N]His incorporation into expected peptides and no evidence of isotope scrambling or incorporation into other peptides in [2H, 15N]8-histidine-PNP.

Steady State and Catalytic Site Chemistry for [15N, 2H]His8-PNP.

Heavy His-labeled PNP showed Michaelis–Menten kinetic parameters and kcat/Km constants similar to native PNP (Fig. S3 and Table 1). Single-turnover rate constants were measured for light and [15N, 2H]His8-PNP for phosphorolysis of guanosine under pseudo first-order conditions. The observed KIE for [15N, 2H]His8-PNP was 1.13 ± 0.02 (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of rate difference to mass differences for native [2H]-, [13C, 15N]-, and [2H, 15N]8-His-PNPs

| Variable | 2H, 13C,15N | 2H | 13C,15N | 2H, 15N-His |

| Mass difference, % | 9.9 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 0.19 |

| On-enzyme KIE | 1.36 ± 0.09 | 1.19 ± 0.08 | 1.18 ± 0.03 | 1.13 ± 0.02 |

Discussion

Steady-State Kinetics.

Increased protein mass in human PNP has small effects on Michaelis–Menten steady-state kinetics and kcat/Km values within experimental errors for unlabeled enzyme (Fig. S3 and Table 1). Mass-independent steady-state kinetics confirmed previous reports for heavy PNP (9), and was also anticipated from the rate-limiting product release in the PNP catalytic mechanism. Protein conformational changes involved in substrate binding and release known from crystallographic analysis and their rates have been measured by temperature jump studies (16–18). Steady-state kinetic constants in PNP are governed by the slow protein conformational changes, and are unaffected by altered protein mass. Mass-dependent vibrational modes from PNP heavy enzymes are not propagated into the substrate binding or product release modes, because any such changes would be reflected in the steady-state kinetic analysis.

Distinguishing 2H Effects from 13C and 15N Effects.

Fully labeled [2H, 13C, 15N]PNP showed a 1.36 enzyme KIE for the chemical step of guanosine phosphorolysis (9). Although attributed to altered bond frequency in the enzyme-reactant complex to slow barrier-crossing, enzyme isotope effects with deuterium labeling have been questioned because of the possibility that physical differences between carbon–hydrogen and carbon–deuterium may alter protein architecture (11, 19). We tested that hypothesis by separating the deuterium effects from the heavy-atom 13C and 15N effects in the [2H]PNP and [13C, 15N]PNP enzymes.

[2H]PNP is 5.3% heavier than natural abundance PNP. If KIEs from fully labeled [2H, 13C, 15N]PNP are dominated by carbon–deuterium properties, most of the enzyme KIE value of 1.36 should appear in [2H]PNP. Catalytic site chemistry for [2H]PNP was 1.19 ± 0.08, and proportional to the mass effect found in fully labeled PNP. Carbon–deuterium labeling throughout the protein does not account for the previously reported heavy enzyme effects.

[13C, 15N]PNP gave a mass increase of 5.6% relative to natural abundance PNP and eliminated deuterium effects. The chemical rate constant for guanosine phosphorolysis in [13C, 15N]PNP was 1.19 ± 0.03 (Fig. 4 and Table 2). The sum of the enzymatic heavy KIE values from [2H]PNP and [13C, 15N]PNP equals the value for [2H, 13C, 15N]PNP. We conclude that PNP heavy-enzyme chemistry rate reductions are proportional to the difference in mass. The results support mass-dependent coupling of enzymatic bond vibrations to catalytic site barrier-crossing with no effects on the slow conformational dynamics that govern steady-state kinetics in PNP. However, these fully labeled enzyme results do not resolve local catalytic site effects from more global protein motion effects where the mass perturbation might be coupled into slower global dynamics to influence the barrier crossing.

Distinguishing Local Mass Effects from Global Effects.

The catalytic site of PNP holds phosphate and guanosine in favorable geometry for the migration of the ribosyl anomeric carbon toward the activated phosphate (20, 21). Three His are involved in direct contact to the reactants (Fig. 3). His64 and His86 are in contact to the phosphate nucleophile, and His257 directs the 5′-hydroxyl group in position to assist in formation of the ribocation transition state (20). Heavy-enzyme effects might arise from global changes in the protein dynamic architecture or from direct femtosecond bond contacts between residues of the catalytic site and the reactants. We hypothesize that the change in local catalytic site bond frequency is responsible for catalytic site barrier-crossing in the chemical step (9).

In addition to the three His located in the active site, the remaining five His residues are located in the periphery of the enzyme with Cα distances of 31.6 Å (His20), 30.2 Å (His23), 25.5 Å (His104), 15.1 Å (His135), and 24.2 Å (His230) from the anomeric carbon mimic of a transition state analog bound in the catalytic site (PDB ID code 3PHB). If local catalytic site dynamics are responsible for the mass-dependent chemistry, a significant effect should be expected in the His8-labeled PNP. However, these amino acids increase the enzymatic mass by only 0.19%. If mass effects are linked to global conformational effects over multiple timescales, the mass change induced by the His will be insignificant.

No significant change in kcat/Km was observed as a result of His labels (Table 1 and Fig. S3). However, the chemistry rate decreased to give an enzyme KIE of 1.13 ± 0.03 (Fig. 4 and Table 2). The significant decrease in chemistry rate from altered His mass establishes a direct link between catalytic site dynamics and transition state barrier-crossing. Global mass effects from the His labels are negligible relative to any of the fully labeled constructs of PNP because the mass difference for [15N, 2H]His8-labeled PNP is only 0.19% above natural abundance PNP.

Atomic motion alters local internuclear distances between enzyme and reactants by as much as an angstrom on the femtosecond timescale. These stochastic motions occur in all nonconstrained coordinate dimensions. An example is provided by the motion of catalytic site atoms in PNP for the 250 fs, including transition-state formation and barrier-crossing (7). Stochastic femtosecond motions at the catalytic site continue until simultaneous optimization of all enzyme–reactant contacts removes the energetic barrier to catalysis. The probability of optimizing multiple geometric interactions simultaneously is small. For atomic motions occurring on the 10-fs timescale, the dynamic search process must occur over 109 times to achieve barrier crossing for PNP on the millisecond timescale. Substitution of heavy His at the active site alters the bond frequency motion and thus slows the search for the transition state. The change in chemistry rates is small because the mass difference alters the bond frequency by only a limited amount, in the same way that reactant secondary kinetic isotope effects are small. Nevertheless, the ability to observe significant changes provides support for coupling of local catalytic site bond vibrational modes to influence the probability of transition-state formation.

Electrostatic Considerations.

Molecular electrostatics are unchanged by altered nuclear mass according to the Born–Oppenheimer approximation. However, the femtosecond change in internuclear distances creates a fluctuating change in the electrostatic field experienced by the reactants. When the femtosecond search optimizes the electrostatic field, the energetic barrier to the transition state diminishes to permit barrier-crossing. Isotope-specific and residue-specific isotope effects with PNP establish that local femtosecond motions of enzymes are probabilistically linked to transition-state formation. A local stochastic, fast dynamic sampling of the Michaelis complex geometries locates the rare conformations to optimize distances and lead to barrier-crossing.

Materials and Methods

Deuterium oxide (99.9%), [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 6-2H7]glucose, [U-13C6, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 6-2H7]glucose, l-[2H5, 15N3]histidine (98%), and [15N]ammonium chloride were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. All other chemicals and reagents were obtained from commercially available sources and were used without further purification.

Production of Natural Abundance-, [2H]-, and [13C, 15N]PNPs.

Natural abundance (light) PNP was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring a pCR-T7/CT-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) containing the encoding sequence for human PNP, as previously described (22). Heavy PNPs were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS (Invitrogen) cells containing the same construct. [2H]PNP was expressed in cells grown in M63 minimum medium prepared in D2O supplemented with [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 6-2H7]glucose (3 g/L), containing 100 mg/mL ampicillin, at 37 °C. [13C, 15N]PNP was expressed in cells grown in M63 minimum medium prepared in H2O supplemented with [U-13C6, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 6-2H7]glucose (3 g/L) and [15N] ammonium chloride, containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin, at 37 °C. After an OD600 = 1.0 was reached, protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. Cells were allowed to grow for additional 24 h and harvested by centrifugation. Both light and heavy PNPs were purified as previously published (23) using an AKTA FPLC system (GE) at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm using the predicted extinction coefficient of 29,910 M−1⋅cm−1 (expasy.org). Subunit molecular mass was determined by MALDI-TOF-MS.

Production of [15N, 2H]His8-PNP.

Heavy His-labeled [15N, 2H]His8-PNP was expressed using the histidine auxotroph strain SB3930 obtained from the E. Coli Genetic Stock Center at Yale University. Cells were grown at 37 °C in M63 minimum medium supplemented with glucose (3 g/L), l-[2H5, 15N3]histidine (0.2 mg/mL), and 100 μg/mL ampicillin. IPTG (1 mM final) was added at an OD600 of 0.8–1.0. Cells were grown overnight and harvested by centrifugation. [15N, 2H]His8-PNP was purified to near homogeneity following the same procedure previously described for native PNP (23).

Steady-State Kinetic Analysis.

Steady-state kinetic parameters were determined by measuring initial reaction rates as a function of guanosine or inosine concentration at 25 °C. The decrease in absorbance at 258 nm upon conversion of guanosine to guanine (Δε = −5,500 M−1⋅cm−1) (24) was monitored in a Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Varian). Guanosine phosphorolysis reactions contained 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM inorganic phosphate (Pi) pH 7.4, varying guanosine concentrations (10–160 μM), and 20 nM of light or heavy PNPs. Kinetic parameters were obtained by data fitting to Eq. 1, where ν is the initial velocity, V is the maximal velocity, S is the concentration of variable substrate, and Km is the Michaelis constant for the variable substrate.

| [1] |

Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Analysis.

Single-turnover catalytic site rate constants were determined by monitoring the increase in fluorescence upon formation of enzyme-bound guanine (25) in an SX-20 stopped-flow spectrofluorometer (Applied Photophysics; dead time ≤1.25 ms) at 25 °C. The excitation wavelength was 280 nm with slit width of 1 mm, and a fluorescence signal above 305 nm (with slit width of 1 mm) was selected using a WG305 Scott filter positioned between the photomultiplier and the sample cell. Fluorescence change was monitored for 250 ms, and 1,000 points were collected for each individual rate curve. Syringe 1 contained 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM Pi (pH 7.5), and either light or heavy PNP at 30 μM (15 μM postmixing concentration). Syringe 2 contained 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM Pi (pH 7.4), and 10 μM guanosine (5 μM postmixing concentration).

NanoUPLC-MS/MS Analysis for [15N, 2H]His8-PNP.

Purified native or labeled PNP proteins (20 µg) in 50 mM NH4HCO3 (Sigma) and 0.01% Protease Max (Promega) were reduced with 5 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (Thermo Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by alkylation with 25 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma) for 30 min at room temperature, in the dark. The sample was digested with trypsin (Trypsin Gold; Promega) at a ratio of 1:100, 37 °C, shaken for 3 h. An aliquot was diluted 50-fold with 2% (vol/vol) acetonitrile (Fisher) in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (Pierce) and analyzed by nanoUPLC-MS/MS. C18 reversed-phase nanoUPLC-MS/MS analysis was performed using a linear ion trap LTQ-XL mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan) connected to a Dionex rapid separation LC UPLC system (Thermo Scientific).

Data Analysis.

The MS/MS raw data files were converted to a Mascot generic format file using Proteome Discoverer version 1.3. Protein database search was performed using the Mascot (version 2.4.1) search engine against taxonomy of all entries for Homo sapiens in the NCBInr database. The search parameters included two missed cleavages; peptide charge of +2 and +3; peptide tolerance of 2 Da; MS/MS tolerance of 0.6 Da; carbamidomethylation on Cys as a fixed modification and variable modifications: deamidation on Asn and Gln residues; oxidation on Met; and 15N3 and 2H5 label on His residues.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Jihyeon Lim and Jennifer T. Aguilan from the Laboratory of Macromolecular Analysis and Proteomics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine for their analysis of the nanoUPLC-MS/MS data with [15N, 2H]His8-PNP and other labeled PNPs. This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences NIH Research Grants GM068036 and GM041916 (to V.L.S.) and NIH Training Award K12 GM102779. This work used UltrafleXtreme analysis purchased with National Institutes of Health Shared Instrumentation Grant 1S10RR025128 (to Ruth H. Angeletti, Albert Einstein College of Medicine).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1513956112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Boehr DD, McElheny D, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. The dynamic energy landscape of dihydrofolate reductase catalysis. Science. 2006;313(5793):1638–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1130258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammes GG, Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. Flexibility, diversity, and cooperativity: Pillars of enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry. 2011;50(48):10422–10430. doi: 10.1021/bi201486f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henzler-Wildman KA, et al. Intrinsic motions along an enzymatic reaction trajectory. Nature. 2007;450(7171):838–844. doi: 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora K, Brooks CL., 3rd Multiple intermediates, diverse conformations, and cooperative conformational changes underlie the catalytic hydride transfer reaction of dihydrofolate reductase. Top Curr Chem. 2013;337:165–187. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz SD, Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states and dynamic motion in barrier crossing. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(8):551–558. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Núñez S, Antoniou D, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Promoting vibrations in human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. A molecular dynamics and hybrid quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical study. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(48):15720–15729. doi: 10.1021/ja0457563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saen-Oon S, Quaytman-Machleder S, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Atomic detail of chemical transformation at the transition state of an enzymatic reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(43):16543–16548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808413105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quaytman SL, Schwartz SD. Reaction coordinate of an enzymatic reaction revealed by transition path sampling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(30):12253–12258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704304104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva RG, Murkin AS, Schramm VL. Femtosecond dynamics coupled to chemical barrier crossing in a Born-Oppenheimer enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(46):18661–18665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114900108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kipp DR, Silva RG, Schramm VL. Mass-dependent bond vibrational dynamics influence catalysis by HIV-1 protease. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(48):19358–19361. doi: 10.1021/ja209391n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Singh P, Czekster CM, Kohen A, Schramm VL. Protein mass-modulated effects in the catalytic mechanism of dihydrofolate reductase: Beyond promoting vibrations. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(23):8333–8341. doi: 10.1021/ja501936d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pudney CR, et al. Fast protein motions are coupled to enzyme H-transfer reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(7):2512–2517. doi: 10.1021/ja311277k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oppenheimer JR. On the quantum theory of the polarization of impact radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1927;13(12):800–805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.13.12.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoniou D, Ge X, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Mass modulation of protein dynamics associated with barrier crossing in purine nucleoside phosphorylase. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3(23):3538–3544. doi: 10.1021/jz301670s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalckar HM. Differential spectrophotometry of purine compounds by means of specific enzymes; studies of the enzymes of purine metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1947;167(2):461–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghanem M, Zhadin N, Callender R, Schramm VL. Loop-tryptophan human purine nucleoside phosphorylase reveals submillisecond protein dynamics. Biochemistry. 2009;48(16):3658–3668. doi: 10.1021/bi802339c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kline PC, Schramm VL. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Catalytic mechanism and transition-state analysis of the arsenolysis reaction. Biochemistry. 1993;32(48):13212–13219. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kline PC, Schramm VL. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Inosine hydrolysis, tight binding of the hypoxanthine intermediate, and third-the-sites reactivity. Biochemistry. 1992;31(26):5964–5973. doi: 10.1021/bi00141a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohen A. Role of dynamics in enzyme catalysis: substantial versus semantic controversies. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48(2):466–473. doi: 10.1021/ar500322s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho MC, et al. Four generations of transition-state analogues for human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(11):4805–4812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913439107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng H, Lewandowicz A, Schramm VL, Callender R. Activating the phosphate nucleophile at the catalytic site of purine nucleoside phosphorylase: A vibrational spectroscopic study. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(31):9516–9517. doi: 10.1021/ja049296p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murkin AS, et al. Neighboring group participation in the transition state of human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry. 2007;46(17):5038–5049. doi: 10.1021/bi700147b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva RG, et al. Cloning, overexpression, and purification of functional human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;27(1):158–164. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00602-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bzowska A, Kulikowska E, Shugar D. Properties of purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) of mammalian and bacterial origin. Z Naturforsch C. 1990;45(1-2):59–70. doi: 10.1515/znc-1990-1-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghanem M, et al. Tryptophan-free human PNP reveals catalytic site interactions. Biochemistry. 2008;47(10):3202–3215. doi: 10.1021/bi702491d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]