Significance

Plant roots associate with the diverse microbial community in soil and can establish mutualistic relationships with microbes. The genetic characterization of the plant microbiome (total microbiota of plants) has intensified, but we still lack experimental proof of the ecological function of the root microbiome. Without such an understanding, the use of microbial communities in sustainable agricultural practices will be poorly informed. Through continuous cropping of a seed-sterilized native plant, we inadvertently recapitulated a common agricultural dilemma: the accumulation of phytopathogens. Experimental inoculations of seeds with native bacterial consortium during germination significantly attenuated plant mortality, demonstrating that a plant’s opportunistic mutualistic associations with soil microbes have the potential to increase the resilience of crops.

Keywords: Fusarium, microbiome function, plant disease resistance, Nicotiana attenuata, Alternaria

Abstract

Plants maintain microbial associations whose functions remain largely unknown. For the past 15 y, we have planted the annual postfire tobacco Nicotiana attenuata into an experimental field plot in the plant’s native habitat, and for the last 8 y the number of plants dying from a sudden wilt disease has increased, leading to crop failure. Inadvertently we had recapitulated the common agricultural dilemma of pathogen buildup associated with continuous cropping for this native plant. Plants suffered sudden tissue collapse and black roots, symptoms similar to a Fusarium–Alternaria disease complex, recently characterized in a nearby native population and developed into an in vitro pathosystem for N. attenuata. With this in vitro disease system, different protection strategies (fungicide and inoculations with native root-associated bacterial and fungal isolates), together with a biochar soil amendment, were tested further in the field. A field trial with more than 900 plants in two field plots revealed that inoculation with a mixture of native bacterial isolates significantly reduced disease incidence and mortality in the infected field plot without influencing growth, herbivore resistance, or 32 defense and signaling metabolites known to mediate resistance against native herbivores. Tests in a subsequent year revealed that a core consortium of five bacteria was essential for disease reduction. This consortium, but not individual members of the root-associated bacteria community which this plant normally recruits during germination from native seed banks, provides enduring resistance against fungal diseases, demonstrating that native plants develop opportunistic mutualisms with prokaryotes that solve context-dependent ecological problems.

Eukaryotes maintain many complex relationships with the microbes they host, which can be so abundant and diverse that they frequently are considered a eukaryote’s second genome. The complex relationships mediated by microbial associates are being revealed rapidly, thanks to the advances in sequencing, microbial culturing techniques, and the reconstitution of associated microbial communities in gnotobiotic systems (1, 2), even if some of these putative functional roles may need to be evaluated more critically (3).

When plants germinate from their seed banks, they typically acquire a selection of the diverse fungi and bacteria that exist in native soils, and a subset of this community becomes root-associated. The best characterized are the bacterial microbiomes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Approximately half of the bacterial community in the plant root is representative of the soil flora; the remainder is a conserved core consisting of a smaller number of bacterial lineages from three phyla: Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes (2, 4). Because these bacterial communities occur in nondiseased plants, they are thought to represent commensalistic or possibly mutualistic associations.

Root-associated microbes could benefit plants in many ways, and a recent review (5) highlighted the parallel functional roles of the microbiomes of the human gut and those of plant roots. The best-characterized beneficial functions for plants are (i) the plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), which promote growth by a variety of direct and indirect means that include increasing nutrient availability, interfering with ethylene (ET) signaling, and preventing diseases (6), and (ii) the bacteria that elicit induced systemic resistance (ISR) (7) by activating jasmonic acid (JA) and ET signaling (8). PGPR and ISR have been studied in a variety of cultivated and model plants, usually with model microbes (5), but little is known about their ecological context or whether they increase the growth and fitness of native plants. Whether PGPR and ISR functions occur among the well-characterized root-associated bacterial communities of Arabidopsis, either collectively or individually, also remains unknown.

The well-described agricultural phenomenon of disease-suppressive soils that harbor microbiomes that suppress particular soil-borne pathogens (9) illustrates the complexity of the dynamics involved. Native soils have a certain degree of pathogen-suppressive ability, frequently seen when a crop is grown continuously in a soil, suffers an outbreak of a disease, and subsequently becomes resistant to the disease (5). Perhaps the mechanisms involved are best understood in a root disease of wheat caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var Tritici infections, known as “take-all” disease. After many years of continuous wheat cropping with several disease outbreaks, the disease suddenly wanes, apparently because of the build-up of antagonistic Pseudomonas spp. (9). Whether any of these interactions also occur in native plants remains unknown.

Nicotiana attenuata, a native annual tobacco of North America, germinates from long-lived seed banks to grow in the immediate postfire environment (10). When N. attenuata seeds germinate from their seed banks, they acquire a root-associated microbiome from their native soils which has been characterized by pyrosequencing and culture-dependent approaches (11–14). The composition of the root-associated microbiome is not influenced by a plant’s ability to elicit JA signaling (14), but ET signaling, as mediated by the ability both to produce and to perceive ET, plays a decisive role in shaping the “immigration policy” for the root-associated microbiome (12). A certain Bacillus strain, B55, was isolated from the roots of an ET-insensitive N. attenuata plant (35S etr-1) and was able to rescue the impaired-growth and high-mortality phenotype of ET-insensitive plants under field conditions (15). Beneficial effects were attributed to B55’s ability to reduce sulfur and produce dimethyl disulfide, which N. attenuata uses to alleviate sulfur deficiencies. This rescue provided one of the first demonstrations that the soil bacteria recruited by plants during germination can form opportunistic mutualistic relationships with their host based on the host plant’s ecological context. Here we provide a second example that involves protection against a sudden wilt disease, which accumulated in a field plot after consecutive planting of N. attenuata seedlings.

Results and Discussion

Emergence of the Sudden Wilt Disease.

For the past 15 y, we have planted the wild tobacco N. attenuata continuously in a field plot at Lytle Ranch Preserve, located in the plant’s native environment of the Great Basin Desert, Utah. Seeds were germinated on sterilized medium, and young plants were first transferred to Jiffy peat pellets, to acclimate them to the environmental conditions, before they were planted in the field plot (Movie S1).

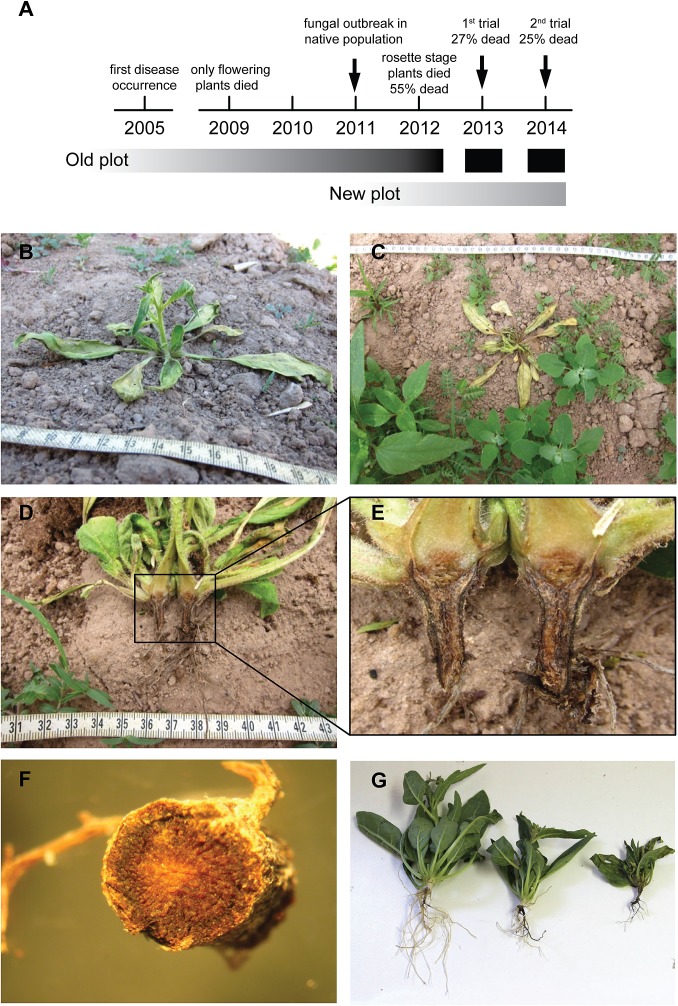

We observed the sporadic occurrence of a sudden wilt disease 8 y ago, which first affected elongated plants, causing them to wilt and die rapidly. In addition to the wilting symptoms, the normally white roots became black, and the two symptoms together (wilting plus black roots) were considered diagnostic of a plant being affected by the sudden wilt disease (Fig. S1). Plant mortality increased gradually over the years, and plants began to show symptoms at earlier developmental stages. By the end of the field season 2012, more than half (584 of 1,069) of the N. attenuata plants on the original (hereafter, “Old”) plot, including different transgenic lines, showed these wilting symptoms and died; this value likely underestimates the actual death rate, because plants replaced during the early establishment stage (during the first 10 d after planting) were not included in this count. The sudden wilt disease seems to be specific for N. attenuata, because other plants or weeds growing on the plot were unaffected (Fig. S1). Interestingly, Nicotiana obtusifolia, which also is native to the Great Basin Desert, seemed to be less affected during the 2012 field season, because only 2 of 12 N. obtusifolia plants on the Old plot died. The emergence of the sudden wilt disease recapitulates a common agricultural dilemma that results from the accumulation of plant pathogens after continuous cropping and reuse of the same area for several years (16, 17). To avoid this problem, crop rotation is nearly as old as agriculture itself and entails the use of different crops in succession to interrupt the disease cycle of plant pathogens (18, 19). Because crop rotation was not an option for our research program, we compared the effectiveness of different disease-control methods, including biocontrols, fungicide treatment, and soil amendments, for N. attenuata planted in the Old plot.

Fig. S1.

Symptoms of the sudden wilt disease. (A) Disease symptoms first occurred only sporadically in our field plot in elongated and flowering plants and later were also observable in rosette-stage plants. Regular field experiments on the Old plot were ended in 2012 because of the unacceptably high plant mortality. Total plant mortality was recorded during the last three field seasons. (B) Sudden wilt disease symptoms characterized by dry or flaccid leaves developed within 1 or 2 d in N. attenuata plants. (C) The wilting was specific to N. attenuata; surrounding plants were not affected, and the surrounding soil usually was still moist. (D–F) The signature characteristic of a diseased plant was the development of black roots; the discoloration was visible on the outside as well as in longitudinal sections. The occurrence of wilting together with the black roots was diagnostic of a plant being affected by the sudden wilt disease. (G) Plants with differently pronounced disease levels were observed during the 2014 field season and illustrate the course of the disease. Wilting first was observed only in elongated plants (here with mild symptoms and mainly white roots) but during the last three field seasons appeared in younger plants also (here with marked symptoms and completely black roots).

Alternaria and Fusarium Fungal Phytopathogens Were Abundant in the Roots of Diseased Plants.

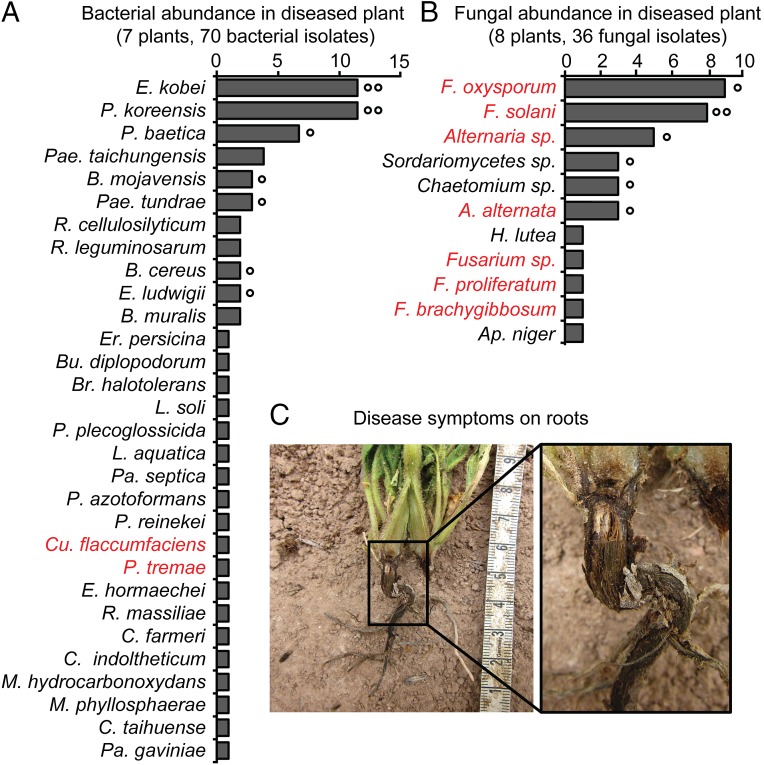

To identify and work with the microbial culprits of the sudden wilt disease, we isolated bacteria and fungi from the roots of diseased N. attenuata plants grown in the Old plot. A total of 36 fungal and 70 bacterial isolates were retrieved from the roots of diseased plants (Fig. 1 and Dataset S1). Based on the sudden wilt symptoms and the literature, we expected to find the bacterial plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum, because its ability to cause wilting symptoms in solanaceous plants is well known (20). Among 70 bacterial isolates, the only potential plant pathogens were Pseudomonas tremae and Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens (21), but both were recovered at low frequencies (≤2%). In contrast, isolates of plant pathogenic fungi of the Fusarium and Alternaria genera were abundant (Fig. 1). Fusarium oxysporum was the most abundant (25%), followed by Fusarium solani (22%) and different Alternaria species, which together represented ∼21% of the isolates.

Fig. 1.

Abundance of bacteria and fungi isolated from the roots of diseased N. attenuata plants. Abundance of culturable bacteria and fungi isolated from native field-grown plants exhibiting the sudden wilt disease symptoms. Potential plant pathogens are in red font. (A) Only two potential bacterial pathogens (C. flaccumfaciens and P. tremae) were found in the 70 members of the bacterial community retrieved from the roots of seven diseased plants. (B) In contrast, potential fungal pathogens (Alternaria and Fusarium) were abundant among the 36 culturable isolates of the fungal community from the roots of eight diseased plants. Isolates, which were found in two or more or four or more plants are indicated by (°) and (°°), respectively. Bacterial genus acronyms: B, Bacillus; Br, Brevibacterium; Bu, Budvicia; C, Chryseobacterium; Ci, Citrobacter; Cu, Curtobacterium; E, Enterobacter; Er, Erwinia; L, Leifsonia; M, Microbacterium; P, Pseudomonas; Pa, Pantoea; Pae, Paenibacillus; R, Rhizobium. Fungal genus acronyms: A, Alternaria; Ap, Aspergillus; F, Fusarium; H, Hypocrea. (C) Symptoms of the sudden wilt disease in field-grown N. attenuata plants included black coloration of the roots. For details see Fig. S1.

Wilt diseases in solanaceous plants can be caused by various pathogens, such as Fusarium wilt (F. oxysporum) or bacterial wilt (R. solanacearum) (22, 23). Because Fusarium spp. and Alternaria spp. were isolated in abundance from diseased roots, we considered them to be the potential causal agents of the sudden wilt disease. The repeated planting of N. attenuata violated the natural disease-avoidance strategy of the plant’s normally ephemeral, fire-chasing populations and likely led to an accumulation of pathogens. Moreover because our experimental procedures use sterile medium for germination and a preadaption period in Jiffy peat pellets, the roots’ contact with the bacterial community in the native soil in the field occurs weeks after germination, and one of the strong inferences of this study is that the recruitment of beneficial microbes occurs soon after germination. Hence, these plants may lack the opportunity to recruit microbes from the surrounding soil at an early stage of their development and therefore lack the appropriate microbial community required for pathogen resistance. Whether plants acquire bacteria during the early stage of growth in Jiffy pellets is not known, but if they do, then these bacterial recruits are unable to protect the plants against the wilt disease. Furthermore, previous work (14) demonstrated that isogenic field-grown N. attenuata plants harbor highly divergent bacterial root communities that likely reflect spatial differences in soil microbial communities; from this variability we infer that microbes acquired during growth in the Jiffy pellets do little to shape the plant bacterial community that is retained throughout growth in the field (14). An additional vulnerability factor that likely contributed to the accumulation of specialized pathogens (24) is that our plantation populations are de facto genetic monocultures, in stark contrast with the high genetic diversity of native populations, which likely is a result of the long-lived seed banks and the differential recruitment of different cohorts into populations after fires (25, 26).

In Vitro Tests of Fungicide, Bacterial, and Fungal Treatments Reduced N. attenuata Seedling Mortality.

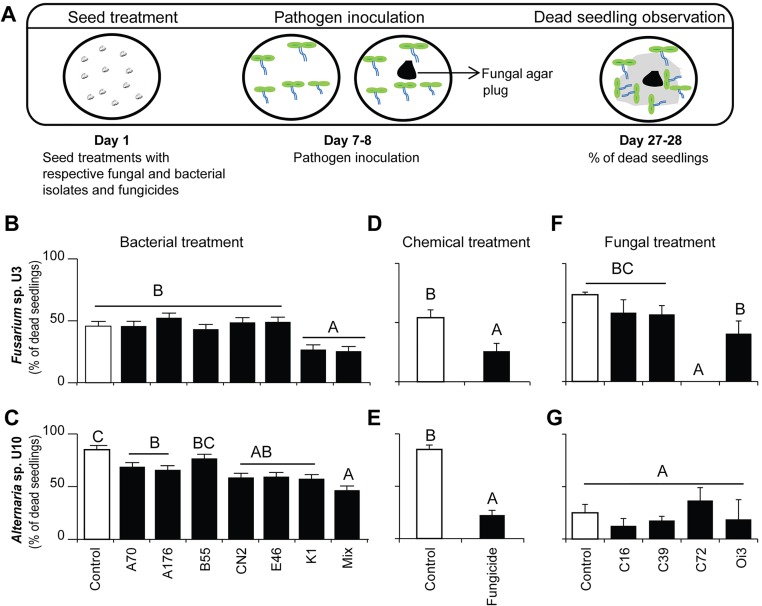

A native fungal outbreak was used to develop an in vitro pathosystem for N. attenuata with native isolates (13). In this study, we used this pathosystem to test different strategies of minimizing the occurrence of the sudden wilt disease in the field.

For the in vitro tests, we used two fungal isolates: Fusarium oxysporum U3, isolated from the roots of diseased N. attenuata plants from the Old plot, and Alternaria sp. U10 from the established pathosystem described in ref. 13. With these fungi we examined biocontrol strategies and fungicide application that could provide resistance. Biocontrols are beneficial microbes that protect plants from microbial pathogens (27). For the biocontrol treatments, we used four native fungal isolates, Chaetomium sp. C16, C39, and C72 and Oidodendron sp. Oi3, which were isolated from diseased plants but were reported to be potential biocontrol agents (28, 29), and six native bacterial isolates (Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus E46, Bacillus cereus CN2, Bacillus megaterium B55, Bacillus mojavensis K1, Pseudomonas azotoformans A70, and Pseudomonas frederiksbergensis A176), which had been isolated from the roots of healthy N. attenuata plants from the same field location (12, 14). The selection of these bacterial isolates was based on in vitro plant growth-promoting effects on N. attenuata (15, 30); the isolates had been reported as biocontrol agents in the literature (28, 29, 31).

The treatment of the seeds with fungicide significantly reduced seedling mortality when seedlings were challenged with Fusarium sp. U3 and Alternaria sp. U10 [U3 t(1,8) = 2.52, P < 0.03; U10 t(1,8) = 8.23, P < 0.0001, t-test] (Fig. S2). The treatment of the seeds with bacteria was most effective when all six strains were mixed, which significantly reduced mortality from both fungal pathogens [U3 F7,32 = 6.6, P < 0.0001; U10 F7,32 = 9.1, P < 0.0001, ANOVA, least significant difference (LSD)] (Fig. S2). Fungal isolates showed inconsistent effects, and some appeared to have negative effects on plant growth. Two fungal isolates, Chaetomium sp. C72 and Oidodendron sp. Oi3, were selected for field experiments because they reduced seedling mortality in seedlings inoculated with Fusarium sp. U3 (F4,13 = 11.961, C72, P < 0.0001; Oi3, P < 0.05, ANOVA, LSD) (Fig. S2) without negatively affecting subsequent seedling growth.

Fig. S2.

Inoculation with a mixture of native bacteria, a fungicide, and two native fungal isolates reduced seedling mortality under in vitro conditions. (A) Schematic of the in vitro experimental setup. Seedling mortality was observed in separate infection assays using two fungal pathogens that previously had been isolated from diseased N. attenuata plants in a native population and characterized: Fusarium sp. U3 and Alternaria sp. U10 (3). (B and C). Evaluation of six native bacterial isolates for potential biocontrol abilities. The seeds were inoculated with individual cultures of P. azotoformans A70, P. frederiksbergensis A176, B. megaterium B55, B. cereus CN2, A. nitroguajacolicus E46, or B. mojavensis K1 or with a mixture of all strains (SI Materials and Methods). The mixed inoculation of all six strains had the strongest effects against Fusarium sp. U3 and Alternaria sp. U10 and was selected as the treatment for the field experiments. (D and E) The fungicide seed treatment (Landor; Syngenta) significantly reduced seedling mortality of N. attenuata seedlings infected with fungal pathogens. (F and G) Native fungal isolates were tested for possible biocontrol abilities. The seeds were inoculated with Chaetomium sp. (C16, C39, and C72) or Oidodendron sp. (Oi3) before being infected with fungal pathogens. The C72 and Oi3 treatments were chosen for field experiments because they reduced the mortality of seedlings inoculated with Fusarium sp. U3. Bars represent mean seedling mortality (± SEM, n = 10 plates); the different letters above the bars indicate significant differences in a one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) test; P < 0.05.

In summary, we selected the mixed bacterial inoculation, two fungal isolates (C72 and Oi3), and the fungicide for large-scale tests in the diseased Old plot. The use of biocontrol strains recently has become a popular alternative to conventional chemical treatments. However, biocontrol bacterial strains that can protect plants from phytopathogens under in vitro conditions frequently are less successful under glasshouse conditions and even might be detrimental under field conditions; this context dependence makes the screening of potential biocontrol candidates challenging (32). The use of bacterial or fungal isolates native to the host plant may increase the success rate in screening experiments, because these microbes are likely to be better adapted to their host and its associated environmental conditions than are generalist strains retrieved from culture collections (33). In agriculture, the use of such locally adapted isolates has been shown to decrease the incidence of Fusarium wilt disease in peanut plant (34).

Inoculation with Native Bacterial Isolates Significantly Attenuates Disease Incidence in the Field Without Slowing Plant Growth.

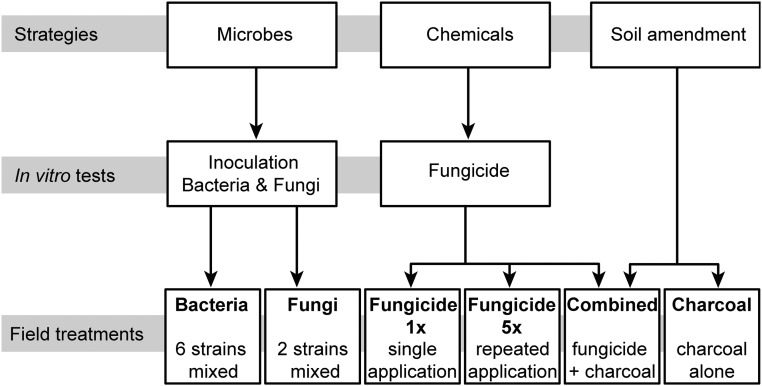

For the field experiments in 2013, we included soil amendment as a third disease-control strategy and combined these strategies to produce seven different treatment groups: control, bacteria, fungi, fungicide 1×, fungicide 5×, charcoal, and charcoal plus fungicide (combined treatment) (Fig. 2). Because the germination of N. attenuata seeds is elicited by smoke, which initiates growth in burned soil, we simulated this soil condition by adding shredded charcoal as a soil amendment at the time of planting (Fig. S3). The application of pyrolyzed plant material (biochar) is a common farming practice that has been shown to have several beneficial effects on plants, increasing crop yields and mitigating disease symptoms (35, 36). For a slow release of the fungicide, we combined the charcoal and fungicide treatments and presoaked the charcoal with the fungicide solution (combined treatment).

Fig. 2.

Workflow of the three main strategies and the treatments used for 2013 field experiment. Of the three main strategies pursued to curb the spread of the disease in the field, the inoculation with microbes (bacteria or fungi) and fungicide treatment were first evaluated under in vitro conditions in the laboratory (Fig. S2). The mixed inoculation with six bacterial isolates, two fungal isolates, and the treatment with a commercially available fungicide in vitro reduced the mortality of N. attenuata seedlings infected with native isolates of fungal pathogens (Fusarium sp. and Alternaria sp.), and these treatments were selected for the field experiments. The combination of the strategies resulted in seven different treatments (including control treatment) that were deployed for the 2013 field experiment. All treatments were applied to N. attenuata seedlings before or during their planting into the field. The repeated fungicide treatment (fungicide 5×) was reapplied four times at 1-wk intervals after planting.

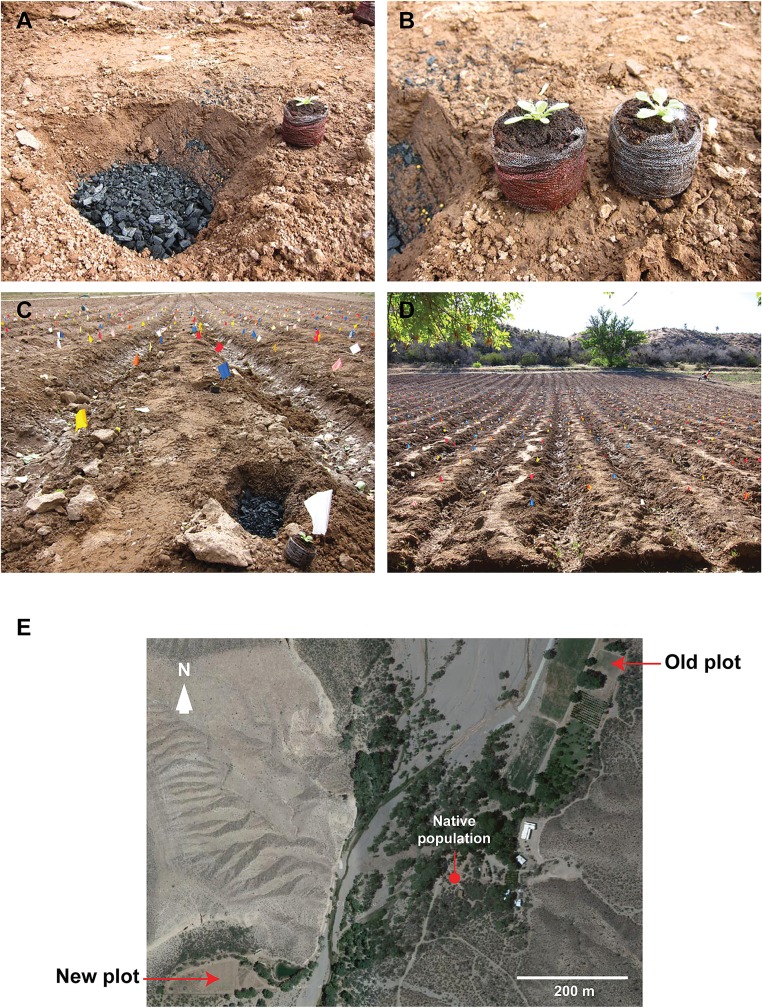

Fig. S3.

Planting of the treatment groups during the 2013 field season. (A) Before planting, charcoal was added to the charcoal and combined treatment groups. (B) Jiffy pots were treated before planting; the applied fungicide solution can be seen by the red color. (C and D) Treatment groups were planted in a randomized design on the lower section of the Old field plot (N 37.1463 W 114.0198), and, as a control experiment, also on the New plot (N 37.1412 W 114.0275). (E) Google Maps view of Old and New field plots ∼900 m apart.

A total of 735 N. attenuata plants from the seven treatment groups were planted in the Old plot. As a control experiment, 261 plants were randomly assigned to the seven treatment groups and planted into the New plot; the two plots are located about 900 m apart, and the New plot had been used only during the previous two growing seasons without any signs of the sudden wilt disease (Fig. S3). The plants from the seven treatment groups were planted in a block in a randomized design (Fig. S4). In the Old plot, the first dead plants were observed quite early. Because these plants were still small, with a rosette diameter of about 5 cm, the black coloration of the roots was not always visible. In such cases, the cause of death could not be assigned to the sudden wilt disease and was categorized as “only wilting symptoms” (Fig. S4). Most of the plants with only wilting symptoms were observed in three treatment groups (fungi, charcoal, and combined) and contributed to the overall high mortality of these groups (Fig. S4). Three days later (15 d post planting, dpp), the majority of the newly dying plants showed the characteristic black roots (Fig. S1), as did the great majority of plants that subsequently died (Fig. S4).

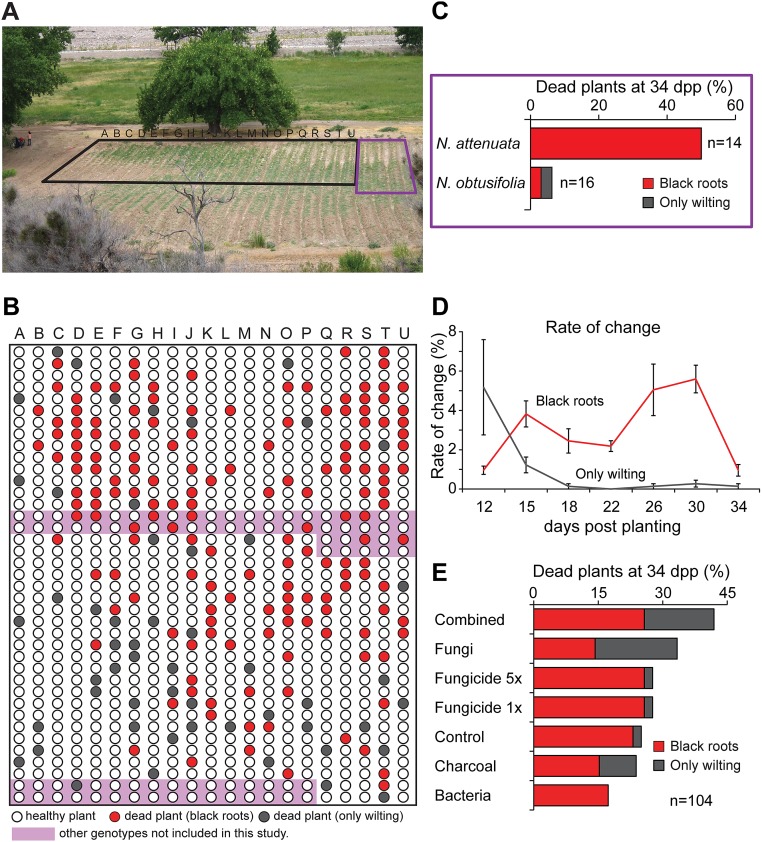

Fig. S4.

Overview of the Old field plot and the rate of change in plant mortality during the 2013 field season. (A) The Old field plot during the 2013 season. The rectangle indicates the lower area of the plot where plants had been planted. This portion of the plot was selected because the greatest number of diseased plants was found in this area during the 2012 growing season. (B) Schematic illustrating the spatial distribution of plants (from the rectangle shown in A), distinguishing plants with the sudden wilt symptoms (wilting and black roots) and plants with only wilting symptoms. The occurrence of the sudden wilt disease was not distributed equally throughout the plot. (C) Mortality rate of N. obtusifolia planted together with N. attenuata in an adjacent block of a separate experiment. (D) The development of plant mortality is shown as the rate of change (percentage dead plants at one observation minus dead plants at previous observation). The error bars reflect the differences among the treatments. Plants with only wilting symptoms were observed mainly at the early time points. (E) Percentage of dead plants at 34 dpp showing black roots or only wilting symptoms. Most plants with only wilting symptoms were found in the fungi, charcoal, and combined (charcoal + fungicide) treatments.

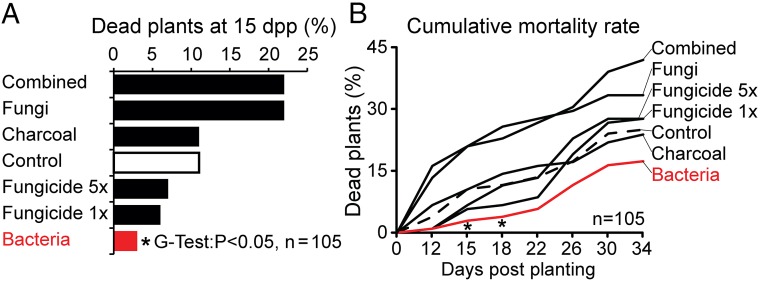

The treatments fungicide 1×, fungicide 5×, and charcoal showed no significant mortality reduction compared with the control treatment, and the fungi and combined treatments, even at 15 dpp, showed elevated mortality rates compared with the controls (Fig. 3). Only the plants inoculated with the mixed bacteria showed a consistently attenuated death rate with a statistically significant reduction compared with the control plants at 15 and 18 dpp p (P < 0.05, G test) (Fig. 3). Over the 22-d observation period, the increase in plant mortality showed two peaks at 15 and 30 dpp (Fig. S4). At the end of the observation period, 219 of 735 plants (26.7%) on the Old plot had died, and 20.2% showed all the symptoms of the sudden wilt disease (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4). As in the previous season, N. obtusifolia plants showed lower mortality than N. attenuata and seemed to be substantially more resistant to the sudden wilt disease (Fig. S4). In contrast, none of the plants from the seven treatment groups on the New plot died or showed symptoms of the sudden wilt disease, even though all treatments and planting procedures were performed identically on the Old and New plots.

Fig. 3.

Efficiency of the different treatments in reducing the mortality of field-grown N. attenuata plants (2013 field season). Plants in the different treatment groups (fungi, charcoal, fungicide 5×, fungicide 1×, bacteria, and combined charcoal + fungicide) were planted together with control plants in a randomized design on the Old (diseased) field plot (see Materials and Methods). (A) Plant mortality at 15 dpp was significantly reduced in the bacterially treated group compared with the control plants (G test: P < 0.05, n = 105 plants per group). (B) The increase in plant mortality was observed every 3 or 4 d for a 22-d observation period. The plants receiving the bacterial treatment had the lowest overall mortality rate. For details of the spatial distribution of plants and the rate of change in mortality see Fig. S4.

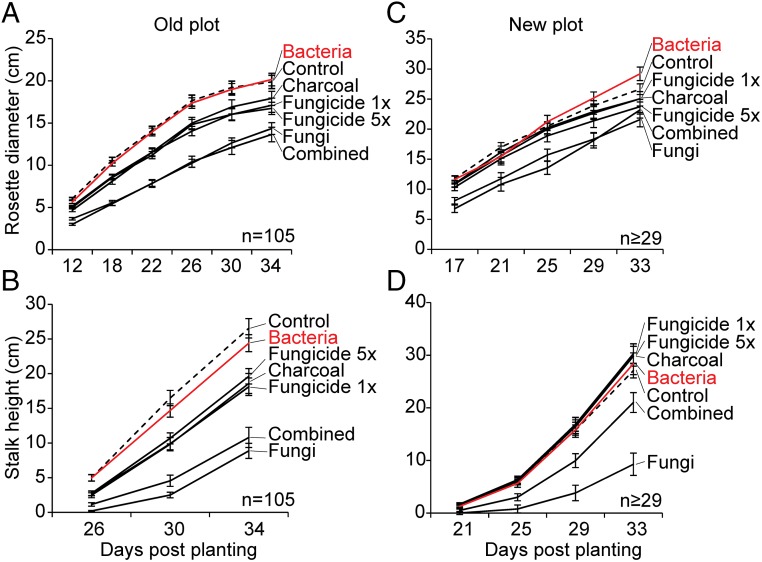

In addition to mortality, we quantified the growth (rosette diameter and stalk height) of all plants from both field plots. The combined and fungi-treated plants had the highest mortality rates and the strongest reductions in growth on both field plots (Fig. 4) (Old plot, rosette diameter, F6,515 = 10.13; P < 0.0001, fungal and combined P < 0.05, ANOVA, LSD; stalk height, F6,515 = 23.66, P < 0.0001 fungal and combined P < 0.05, ANOVA, LSD at 34 dpp. New plot, rosette diameter, F6,254 = 4.09, P = 0.0006, fungal and combined P < 0.05, ANOVA, LSD; stalk height, F6,254 = 14.36, P < 0.0001, fungal and combined P < 0.05, ANOVA, LSD). The remaining treatments (charcoal, fungicide 1×, and fungicide 5×) did not reduce mortality and these plants were distinctly smaller on the Old plot (Fig. 4). The mixed bacteria treatment did not reduce plant growth on either field plot and was the only treatment that consistently reduced plant mortality. We conclude that although the bacteria mixture provided a biocontrol effect against the pathogen, it did not significantly increase plant growth (Old plot, rosette diameter, F6,515 = 10.13. P < 0.0001, bacteria P = 0.9, ANOVA, LSD, stalk height; F6,515 = 23.66, P < 0.0001, bacteria P = 0.9, ANOVA, LSD; for New plot data, see Table S1).

Fig. 4.

Growth parameters of plants in the different treatment groups in two field plots. N. attenuata plants from the different treatment groups (bacteria, charcoal, fungicide 1×, fungicide 5×, fungi, and combined treatment with charcoal + fungicide) were planted together with control plants in 2013 into two field plots (Old and New), and their growth parameters (rosette diameter and stalk height) were quantified. (A and B) Mean rosette diameter and stalk height of the different treatment groups compared with control plants (dotted line) grown in the Old (diseased) plot (± SEM; n = 105 plants per group). (C and D) Mean rosette diameter and stalk height of plants from the different treatment groups compared with control plants (dotted line) grown in the New plot (± SEM; n ≥ 29 plants per group). A comprehensive characterization of 32 traits known to be important for insect resistance and general ecological performance, including hormone levels and defense parameters (Table S1), was conducted on plants grown in the New plot to evaluate the effect of bacterial inoculation on traits not directly related to fungal pathogen resistance.

Table S1.

Traits important for N. attenuata’s ecological performance and insect resistance were compared between bacterially treated and control plants grown in the New field plot during the 2013 field season

| Variable | Test | n | Test statistic | P value |

| Plant-growth parameters | ||||

| Root length | t test | 21 | −0.162 | 0.872 |

| Shoot length | t test | 21 | 0.222 | 0.826 |

| Root/shoot ratio | t test | 21 | −0.454 | 0.653 |

| Rosette diameter | t test | 21 | 0.318 | 0.753 |

| Stem length | t test | 21 | −0.313 | 0.756 |

| Number of branches | t test | 21 | −0.267 | 0.791 |

| Number of buds | t test | 21 | −0.976 | 0.335 |

| Number of flowers | Wilcoxon | 21 | 204.500 | 0.696 |

| Number of seed capsules | Wilcoxon | 21 | 201.000 | 0.522 |

| Chlorophyll | t test | 12 | −1.258 | 0.222 |

| Herbivore damage | ||||

| Grasshopper damage | Wilcoxon | 21 | 187.500 | 0.342 |

| Mirid damage | Wilcoxon | 21 | 186.000 | 0.338 |

| Noctuid damage | Wilcoxon | 21 | 174.000 | 0.238 |

| Flea beetle damage | Wilcoxon | 21 | 230.000 | 0.727 |

| Tree cricket damage | Wilcoxon | 21 | 231.000 | 0.697 |

| Flower volatiles | ||||

| Benzyl acetone flower volatile | Wilcoxon | 16 | 106.000 | 0.415 |

| Leaf volatiles 1 h after W+OS | ||||

| 3(Z)-hexen-1-ol | Wilcoxon | 16 | 30.000 | 0.491 |

| 2(E)-hexen-1-ol | Wilcoxon | 16 | 30.000 | 0.491 |

| Putative alpha-pinene | Wilcoxon | 16 | 22.500 | 0.886 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl acetate | Wilcoxon | 16 | 23.000 | 0.950 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl isobutanoate | Wilcoxon | 16 | 32.000 | 0.345 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl butanoate | Wilcoxon | 16 | 24.500 | 1.000 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl 2-methylbutanoate | t test | 16 | −0.907 | 0.383 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl valerate | t test | 16 | −0.879 | 0.400 |

| Putative sesquiterpene oxide | Wilcoxon | 16 | 25.000 | 0.950 |

| Leaf volatiles 48 h after W+OS | ||||

| 1-Hexanol | t test | 16 | 0.884 | 0.396 |

| 3(Z) hexen-1-ol | Wilcoxon | 16 | 45 | 0.19 |

| Putative alpha-pinene | Wilcoxon | 16 | 29.5 | 0.81 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl isobutanoate | Wilcoxon | 16 | 36 | 0.721 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl butanoate | t test | 16 | 0.336 | 0.742 |

| Putative alpha-terpineol | t test | 16 | 1.442 | 0.174 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl 2-methylbutanoate | Wilcoxon | 16 | 40 | 0.442 |

| 3(Z)-hexenyl valerate | Wilcoxon | 16 | 38 | 0.574 |

| Alpha-duprezianene | Wilcoxon | 16 | 44 | 0.227 |

| Putative sesquiterpene oxide | t test | 16 | 2.185 | 0.048 |

| Phytohormones at W+OS (0 h) | ||||

| JA | t test | 7 | −0.266 | 0.7945 |

| JA-Ile | t test | 7 | −0.171 | 0.867 |

| ABA | t test | 7 | −1.49 | 0.162 |

| Phytohormones 1 h after W+OS | ||||

| JA | t test | 7 | 0.068 | 0.9473 |

| JA-Ile | t test | 7 | 2.042 | 0.0659 |

| ABA | t test | 7 | 0.011 | 0.991 |

| Secondary metabolites at W+OS (0 h) | ||||

| Nicotine | t test | 7 | 0.442 | 0.6661 |

| Caffeoylputrescine | t test | 7 | 0.426 | 0.6792 |

| Chlorogenic acid | t test | 7 | 0.132 | 0.8973 |

| Dicaffeoyl spermidine | t test | 7 | 0.124 | 0.9032 |

| Rutin | t test | 7 | −0.325 | 0.7506 |

| HGL-DTGs | t test | 7 | −0.325 | 0.7507 |

| Secondary metabolites 48 h after W+OS | ||||

| Nicotine | t test | 7 | 0.247 | 0.8094 |

| Caffeoylputrescine | t test | 7 | 0.545 | 0.5977 |

| Chlorogenic acid | t test | 7 | 1.513 | 0.1585 |

| Dicaffeoyl spermidine | t test | 7 | 1.521 | 0.1566 |

| Rutin | t test | 7 | −0.759 | 0.4624 |

| HGL-DTGs | t test | 7 | −0.759 | 0.4624 |

Bacteria Inoculation Did Not Influence Other Plant Performance Traits.

Because our group has studied plant–herbivore interactions with plants germinated under sterile conditions, we were interested in understanding if the bacterial inoculation would alter the expression of traits known to be involved in N. attenuata’s defense responses to attack from its native herbivore communities. We quantified the constitutive and herbivore-induced levels of phytohormones, secondary metabolites, and volatiles as well as plant biomass, reproductive output, and herbivore damage from the native herbivore community in bacterially inoculated plants. None of the 32 parameters analyzed indicated differences between the bacteria-treated and control plants (Table S1), demonstrating that the bacterial inoculations specifically influenced pathogen resistance but not traits essential for herbivore resistance.

Consortium of Bacteria Provide the Protection.

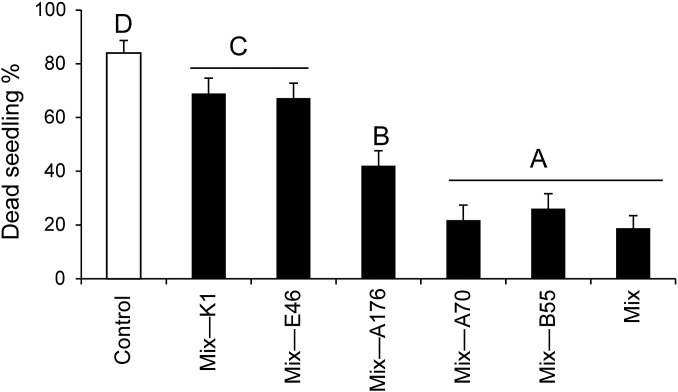

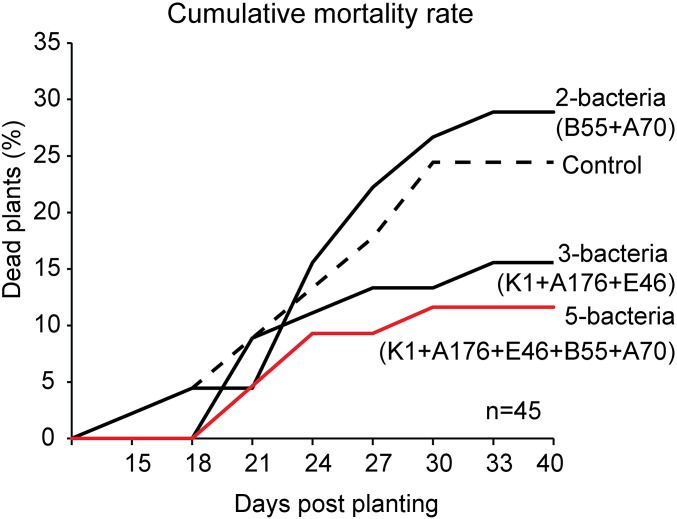

A combination of multiple biocontrol strains can provide improved disease control over the use of single organisms (31). Therefore, under in vitro conditions we examined the effect of bacterial consortia, each lacking a particular strain that had proved effective during the 2013 field season (Fig. S5). Because of regulatory reasons, one strain (CN2), which was classified as a potential S2 strain in Germany, had to be excluded from further experiments (SI Materials and Methods), reducing the mix to five isolates. Consortia lacking the isolates K1, E46, or A176 (mix minus K1, mix minus E46, and mix minus A176) were significantly less effective in reducing mortality in seedlings inoculated with Alternaria sp. U10 than the mix of all five strains (F6,48 = 34.9, P < 0.0001, ANOVA, LSD), indicating that these strains are essential for the protective effect. Deleting the other two strains (mix minus B55 and mix minus A70) did not change seedling mortality, indicating that these bacteria alone could not protect plants effectively from the sudden wilt disease (Fig. S5). Based on these results, the consortia were split into subgroups including either two (B55 + A70) or three bacteria (K1 + A176 + E46), and these subgroups were evaluated in another field trial in 2014. Consistent with the results from the in vitro experiments, the inoculation with three bacteria (K1 + A176 + E46) or the mixture of all five bacteria (K1 + A176 + E46 + B55 + A70) reduced mortality rates in the field by 36 and 52%, respectively (Fig. 5). The inoculation with only two strains (B55 and A70) had no effect. This result indicates that the protection is not explained purely by a founder effect in which rapid root colonization blocks a niche from being colonized by other microbes, including pathogens. The strongest mortality reduction in the field was achieved when these two strains were included in the bacterial mixture (Fig. 5), indicating that they do contribute important synergistic effects to the other strains of the consortium. Because of the lower replicate number (about half as many plants as in 2013), the 2014 results were not statistically significant (P > 0.05, n = 45, G test). Mixtures of commercial biocontrol strains sometimes combine multiple mechanisms of action to enhance the consistency of disease control (37). These synergistic mechanisms include the many different forms of antibiosis, biofilm formation, and founder effects as well as mechanisms that function indirectly through the host by eliciting systemic resistance (e.g., ISR) (7, 38).

Fig. S5.

In comparison with the effects of seedling inoculation with a mixed bacterial consortium consisting of five taxa, the individual absences of three bacterial isolates (K1, E46, and A176) significantly increased seedling mortality under in vitro conditions. Different mixed bacterial consortia were evaluated for potential biocontrol abilities against Alternaria sp. U10. Mixed bacterial consortia lacking one bacterial isolate (e.g., mix minus K1, mix minus E46, and mix minus A176) significantly increased seedling morality. Based on these results, the three-bacteria mixed consortium (K1 + A176 + E46) and two-bacteria mixed consortium (B55 + A70), along with the mixture of all five bacteria, were selected as treatments for the 2014 field experiments. Bars represent mean seedling mortality (± SE; n = 7–10); the different letters above the bars indicate significant differences in a one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s PLSD test; P < 0.05. For the experimental set-up see Fig. S2A.

Fig. 5.

Reproducibility of the disease-suppression effect of bacterial consortia in the 2014 field season. Based on the results of in vitro tests (Fig. S5) we parsed the bacterial consortia into two groups of two (B55 + A70) or three (K1 + A176+ E46) bacteria and compared these groups with the mixture of the five isolates (K1 + A176 + E46 + B55 + A70) in protecting inoculated seedlings from the sudden wilt when planted into the Old plot. Preinoculated plants were planted together with control plants in a randomized design on the Old (diseased) plot (2014 field season; see Materials and Methods). Inoculation with three bacteria (K1 + A176 + E46) or five bacteria (K1 + A176 + E46 + B55 + A70) reduced plant mortality by 36% and 52%, respectively, compared with control plants at 40 dpp (n = 45 plants per group). The inoculation with two bacterial strains (B55 + A70) had no significant effect in reducing the rate of death compared with noninoculated control plants.

Persistence of Biocontrol Bacteria in Late-Stage Plants.

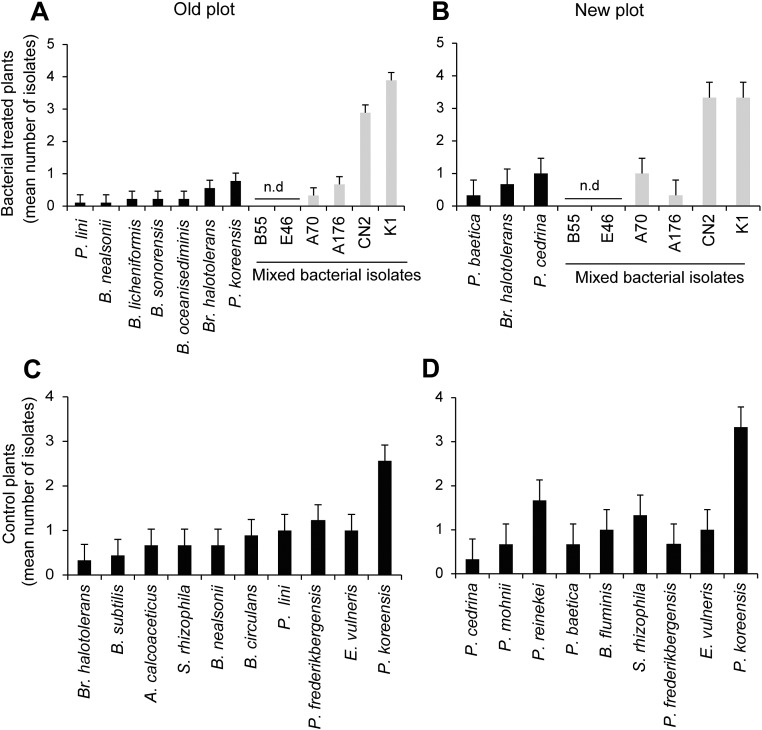

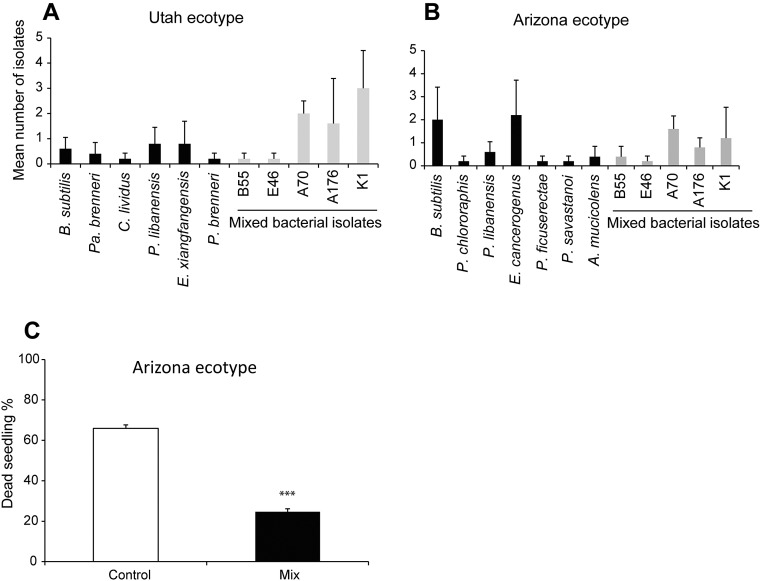

For effective suppression of pathogens under competitive natural conditions, biocontrol strains need to be excellent colonizers and persist as root endophytes (39, 40). In the development of commercial biocontrol agents, the focus has long been on Pseudomonas and Bacillus taxa because of their efficient root-colonizing capacity and their direct pathogen antagonistic characteristics associated with the production of lytic enzymes and antibiotics (41). From our mixed inoculations that included native Pseudomonas and Bacillus taxa, four of six strains were reisolated from the surface-sterilized roots of 2013 field-grown flowering-stage plants harvested 34 dpp. While the Bacillus isolates (K1 and CN2) dominated the bacterial root isolates, Pseudomonas strains (A176 and A70) were recovered at lower frequencies (Fig. S6). Furthermore, an additional test of the robustness of the bacterial association was performed with a second inbred ecotype of N. attenuata, originally collected from Arizona, which was preinoculated with the five isolates at the seed germination stage and planted in the New plot along with the Utah ecotype. All five isolates could be reisolated at the end of the growing season (Fig. S7). Because the Arizona ecotype had been planted only on the New plot, and no plants were lost to the sudden wilt disease, we performed in vitro assays to evaluate the disease-suppressive effect of the bacterial consortium for this ecotype. The consortium of five bacterial isolates also reduced the mortality rate of a Arizona ecotype [t(1,20) = 17.682, P < 0.001, t-test] (Fig. S7). This result indicates that the consortium of isolates provides protection to a second N. attenuata ecotype. The reproducibility and persistence of the members of the mixed bacterial consortium in two N. attenuata ecotypes planted over two field seasons demonstrates that these native bacterial taxa establish stable associations with N. attenuata roots at germination which persist throughout growth under field conditions.

Fig. S6.

Reisolation of the bacteria from healthy field-grown plants at the flowering stage demonstrated the persistence of the inoculated bacterial taxa. In 2013, healthy plants from the control and bacterial treatment groups were harvested at the early flowering stage from both field plots, and the culturable bacterial consortium were isolated. (A and B) Four of the six native bacterial taxa used in the bacterial mix (seed and Jiffy treatment) persisted throughout growth under field conditions and were reisolated from the roots of plants from both field plots. The inoculated roots showed strong colonization by B. cereus CN2 and B. mojavensis K1. The bars represent the mean number of isolates (± SEM; Old field plot: n = 7 roots, 70 isolates; New field plot: n = 3 roots, 30 isolates). (C and D) The control plants showed natural colonization by P. frederiksbergensis, which was also used in the bacterial mixture as A176. Bacterial genus acronyms: A, Acinetobacter; B, Bacillus; Br, Brevibacterium; E, Escherichia; P, Pseudomonas; S, Stenotrophomonas.

Fig. S7.

Reproducibility of the reisolation of the mixed bacterial consortium from Utah and Arizona genotypes in the 2014 field season and the protection effect of the consortium for the Arizona ecotype. Bacterially treated Utah and Arizona genotypes were harvested at the early flowering stage from the New field plot, and the culturable bacterial consortium were isolated. (A and B) All five native bacterial taxa used in the bacterial inoculation treatment (seed treatment only) persisted throughout growth under field conditions of both ecotypes. The persistence of the inoculated bacteria taxa within both ecotypes demonstrates the consistency of the bacterial association with N. attenuata. The bars represent the mean number of isolates (± SEM; n = 5 roots, 50 isolates). Bacterial genus acronyms: A, Achromobacter; B, Bacillus; C, Ciceribacter; E, Enterobacter; P, Pseudomonas; Pa, Pantoea. (C) Under in vitro conditions, the consortium of five mixed bacterial isolates significantly reduced the mortality of the N. attenuata Arizona ecotype inoculated with Alternaria sp. U10 (± SEM; n = 11, P < 0.001, t-test).

Opportunistic Mutualisms and the Opportunities They Afford Agriculture.

Soil arguably harbors the world’s most diverse microbial communities, and when seeds germinate from their seed banks in native soils, they have the opportunity to recruit particular microbial taxa from these marketplaces of potential microbial partners (42). Microbial interactions are commonly categorized as being pathogenic, commensalistic, or mutualistic, as if these traits were fixed features of host and microbial taxa, but most are likely to be context dependent, shifting along the functional spectrum depending on environmental conditions or during the life cycle of the microbe or the plant (43). Root microbiomes are notoriously diverse (2, 4), and some of the diversity may arise from particular microbes being of benefit only to particular hosts under particular conditions or stresses, such as drought or pathogen infestation (44). As shown in this study and others (31), beneficial microbial communities can be acquired from the soil at an early stage during germination and establish beneficial associations that last throughout the entire life cycle of the plants. If plants lack such an early colonization, as in our previous planting procedure, they are exposed suddenly to the field microbiota during planting. Allowing the plant to interact with bacteria either on agar plates or during the Jiffy stage may fill empty niches of the root environment and allow plants to cope better with soil-derived pathogens.

To understand the mechanisms by which a consortium of microbes is recruited soon after germination and maintained in a context-specific manner will require a better understanding of the chemical signals that plants release as they germinate and the opportunities that differences in root morphology and growth afford microbes for colonization. Although organic acids [e.g., malic acid (45)] and certain secondary metabolites [e.g., benzoxazinoids (46)] have been found to mediate the recruitment of particular microbes under in vitro conditions, untargeted metabolomics and genomic approaches are sorely needed to evaluate the processes that are involved when plants are grown under real-world conditions. Crops, likewise, could benefit from location-specific consortia, depending on the region and type of soil in which they are grown.

These opportunistic mutualisms that plants develop with their root-associated microbes have great potential to increase the resilience of crop yields to the ever-changing landscape of abiotic and biotic stresses in agriculture, as many others have argued (31, 33, 47, 48). This work demonstrates that native plants use this strategy, and considerably more attention needs to be focused on the issue for crop plants. Have crop plants lost such abilities, and do they differ from their wild ancestors regarding their root-associated microbiota (49)? Certainly we should reconsider agricultural practices, such as the use of nonspecific antimicrobial seed treatments, that could thwart this important recruitment process. Moreover each plant species likely benefits from recruiting a specialized consortium of bacteria, which needs to be evaluated separately for each plant system. Likewise, evidence of phytoprotective roles of microbes from in vitro experiments should be evaluated under agricultural conditions, because certain microbes (e.g., those used in our fungal treatment) could prove to be detrimental under field conditions. Progress is being made in rapidly querying, in a high-throughput manner, the ability of the diverse soil microbial communities from around the globe to synthesize antimicrobial secondary metabolites (50). We infer from the research reported here that native plants have been querying the soil microbial community throughout evolutionary history to help them solve context-specific challenges, and we need to empower our crop plants to do the same.

SI Materials and Methods

Isolation of Bacterial and Fungal Pathogens from Diseased N. attenuata Plants.

Elongated and rosette field-grown N. attenuata plants displaying symptoms of the sudden wilt disease were shipped to the laboratory facility in Germany within 2 d of excavation. The isolation of potential plant pathogenic bacteria was performed as described in ref. 12 using nutrient agar (Sigma) and Casamino acid-peptone-glucose agar adapted for the isolation of R. solanacearum (52) supplemented with antifungal agents, cyclohexamide and nystatin, both at 25 µg/mL. Isolation of potential pathogenic fungi was carried out as described in ref. 13 on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Fluka) and water agar (53) supplemented with the antibacterial agents streptomycin and penicillin, both at 20 µg/mL. Bacterial and fungal genomic DNA extraction, amplification of 16S rDNA, and internal transcribed spacer and direct sequencing and identification were performed as described in ref. 14 for bacterial isolates and ref. 13 for fungal isolates.

In Vitro Seedling Mortality Assays.

Two plant-protection strategies, (microbial and chemical), were evaluated with an in vitro assay for the protection they afford to N. attenuata seedlings against two different fungal pathogens: Alternaria sp. U10, which was isolated from a native population of diseased N. attenuata plants in Utah (13), and Fusarium oxysporum U3, which was isolated from the roots of diseased plants from the Old plot in 2012.

Potential fungal and bacterial biocontrol isolates were native root-associated isolates from field-grown N. attenuata plants (14). Six native bacterial isolates, Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus E46, Bacillus cereus CN2, Bacillus megaterium B55, Bacillus mojavensis K1, Pseudomonas azotoformans A70, and Pseudomonas frederiksbergensis A176, were chosen because they had promoted plant growth in a previous experiment (30) or had been reported in the literature to be potential biocontrol strains. The four native fungal isolates, Chaetomium sp. C16, C39, and C72 and Oidodendron sp. Oi3, were isolated from diseased plants of the Old field plot; these isolates were not reported in the literature as being pathogenic but had potential biocontrol effects (28, 29). We tested these strains with seedlings challenged with Fusarium and Alternaria fungal pathogens in vitro. Bacillus cereus CN2 was used only in the 2013 experiments because its classification as an S2 strain by the German authorities prohibited its further use.

Potential biocontrol bacterial and fungal isolates were maintained on nutrient agar and PDA medium, respectively. Surface-sterilized N. attenuata seeds were incubated for 12 h with mixed bacterial cultures by combining equal concentrations of all six bacterial isolates (E46, CN2, B55, K1, A70, and A176) from fresh individual bacterial cultures grown overnight to a working concentration of 10−4 cfu/mL in sterile H2O. For the partitioned consortia experiments, five different mixes were made by excluding single individual isolates from the consortia: e.g., mix minus K1 treatment consisted of four different bacteria but not K1 (A70 + A176 + B55 + E46). In this fashion, the following different bacterial consortia were made: mix minus A70, mix minus A176, mix minus B55, and mix minus E46. Arizona ecotype seeds also were treated with the consortium of five bacterial isolates. For each potential biocontrol fungal strain, mycelium was harvested from two 14-d-old fungal plates and dissolved in 1 mL of sterile H2O to incubate sterile N. attenuata seeds for 5 min. For the fungicide treatment, surface-sterilized seeds were treated for 5 min with 1 mL of undiluted fungicide solution (Landor; Syngenta) containing fludioxonil (25 g/L), difenoconazol (20 g/L), and tebuconazol (5 g/L). Bacteria-, fungi-, and fungicide-treated seeds were germinated on Gamborg’s B5 plates (GB5; Duchefa). After 7 d, germinated seedlings were inoculated with fungal pathogens by placing 1-cm-diameter plugs from 14-d-old PDA in the center of seedling plates (see Fig. S2A for the experimental set-up) and were incubated in a growth chamber (22 °C, 65% humidity, 16 h light). Dead seedlings were counted 26 d postinoculation from 10 replicate plates, and the mean percentage of seedling mortality was calculated.

Plant Treatments in the Field.

For the field experiments, wild-type seeds were germinated on Gamborg’s B5 plates (Duchefa) and preinoculated with the mixed bacterial solution or with fungal mycelium, as described above. About 16 d after germination, seedlings were transferred into 50-mm Jiffy peat pots (Jiffy 703, jiffygroup.com) prehydrated with tap water and were placed under shaded conditions for more than 2 wk to adapt the seedlings to the strong sun and relative low humidity of the Great Basin Desert. Well-grown and adapted seedlings were transplanted into the Old plot (54). A detailed description of the field-planting procedure is provided in the supplemental movie (Movie S1).

For the 2013 field season, shortly before planting, Jiffy pots were watered with 10 mL of mixed bacterial or fungal solution. The mixed bacterial cultures were generated by scraping the separately cultivated strains (E46, CN2, B55, K1, A70, and A176) from well-grown nutrient agar plates and diluting them in tap water. The bacterial strains were mixtures of equal volumes pooled from the appropriate strains; all solutions were cloudy, indicating a visually estimated very high OD. The mixture of two potential biocontrol fungal isolates (Chaetomium sp. C72 and Oidodendron sp. Oi3) was prepared in a similar manner by scrapping fungal mycelium from 10 fully grown PDA plates, equally pooled, and diluted in water. For the fungicide treatment, Jiffy pellets were soaked with 15 mL of 1% fungicide solution (Landor; Syngenta) one night before planting. For the charcoal treatment, Royal Oak All-Natural Hardwood Lump Charcoal (Walmart) was chipped into small pieces, and ∼100 g were added to the soil surrounding each plant before planting. For the combined treatment (charcoal and fungicide), 100 g of chipped charcoal were presoaked with 25 mL of 5% fungicide solution (Landor; Syngenta) before planting (Fig. S3 A and B). The treatments were designed to be easily applicable (for a future scale-up) and directly performed during germination (bacteria and fungi), during the Jiffy stage (bacteria, fungi, and fungicide 1×), or during planting (charcoal and combined) (Fig. S3); only the repeated fungicide (fungicide 5×) treatment was performed after planting also. Size-matched plants were planted in a randomized design into the field plot on the Lytle Ranch Preserve, Utah. The experiment was conducted on two separate field plots; of the 819 plants planted in the Old (diseased) field plot, 735 plants were randomly assigned to the seven different treatment groups, as were 261 plants in a New plot (control). The two field plots are ∼900 m apart and are separated by a river (Fig. S3E). During planting, each plant was fertilized with 5 g of Osmocote Smart-Release Plant Food (19-6-12 N-P-K) (Scotts-Sierra Horticulture) suitable for slow nutrient release over 4 mo. The plants in the repeated fungicide (fungicide 5×) treatment were watered every seventh day with 50 mL of 1% fungicide solution poured into a hole located 8–10 cm from the plant. Growth parameters and plant mortality were recorded every 3 or 4 d for a period of 22 d.

For the 2014 field experiment, three bacterial consortia consisting of two (B55 + A70), three (K1 + A176 + E46), or five (K1 + A176 + E46 + B55 + A70) bacteria were tested. Only the seeds were treated with the bacterial mixtures, and in total 180 plants (n = 45 for each group) were planted into the Old field plot (diseased) as described above. The mortality of all plants was recorded every 3 d for 22 d. To evaluate further the reproducibility of the bacterial association with roots, in the 2014 field season, N. attenuata inbred genotypes originally collected from Arizona and Utah were treated with a mixture of five bacterial isolates and were planted at the New field plot as mentioned above.

Phenotypic Characterization of Bacterially Treated Plants in the Field.

A selection of 32 morphological and chemical traits (Table S1) known to be important in mediating N. attenuata’s ecological performance were measured in 7–21 pairs of control plants and plants treated with the mixture of six native root-associated bacteria that had been planted in the New field plot. Replicate values given in Table S1 reflect the number of pairs of plants used in a given analysis.

Leaf chlorophyll content was measured in the largest nonsenescent leaf using a Minolta SPAD-502 (Konica Minolta Sensing, Inc.). Plant growth and reproduction parameters and herbivore damage were assayed once, as previously described (55), before the plants were destructively harvested for biomass measures.

Measurements of foliar and floral volatiles were conducted using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) tubes to absorb volatiles from headspace samples as previously described (56). Herbivore-induced plant volatiles were elicited by wounding leaves followed by the immediate application of Manduca sexta oral secretions (W+OS) (25), and ventilated polyethylene terephthalate (PET) containers were immediately placed around the wounded leaves and around similar mature, nonsenescent control leaves. PDMS tubes were placed in the PET containers for 1 h immediately after treatment and then were removed and stored in tightly closed amber 1.5-mL GC vials (56); a new PDMS tube was placed in the PET container and left there until 48 h after treatment, at which time it also was removed and stored. To measure floral volatiles, a PDMS tube was placed inside a ventilated PET container enclosing a single, newly opened flower as previously described (56) and was exposed to the floral headspace for 12 h, from 20:00–8:00 the following day; then the PDMS tube was removed and stored as described (8), and a new PDMS tube was placed in the headspace, incubated from 8:00 until 20:00, and stored. PDMS samples were kept in sealed vials until thermal desorption (TD)-GC-quadrupole MS (QMS) analysis was performed as described (56). TD-GC-QMS analysis was performed on a TD-20 thermal desorption unit (Shimadzu, www.shimadzu.com) connected to a quadrupole GC-MS-QP2010Ultra (Shimadzu). An individual PDMS tube was placed in an 89-mm glass TD tube (Supelco, www.sigmaaldrich.com), desorbed, and analyzed as described (56). Compounds were identified by comparison of spectra and Kovats retention indices against libraries (Wiley, National Institute of Standards and Technology, eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118615964.html), and, where possible, by comparison with pure standards.

The phytohormones JA and JA-Ile and secondary metabolites nicotine, chlorogenic acid, caffeoyl putrescine, dicaffeoyl spermidine, rutin, and hydroxygeranyllinalool diterpene glycosides (HGL-DTGs) were induced by W+OS treatment (57–59). The first stem leaf was collected as a control sample before the W+OS treatment, and the second and third stem leaves were collected 1 or 48 h after the W+OS treatment for phytohormone or secondary metabolite analysis, respectively. Approximately 100 mg of frozen leaf samples were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and extracted, and the phytohormone and secondary metabolite concentrations were quantified as described in ref. 60. A Varian 1200 LC-ESI-MS/MS system (Varian) was used for phytohormones analysis, and HPLC (Agilent-HPLC 1100 series) coupled to a photodiode array and evaporative light scattering detector (HPLC-PDA-ELSD) was used for the secondary metabolite analysis.

Variables measured in microbially treated and untreated plants were compared using individual t tests. Wilcoxon pairwise tests were used when a variable did not meet the assumptions of parametric tests. All statistics were performed in R-Studio (R Core Team, 2012). P values were not corrected for multiple tests.

Bacterial Reisolation from Field-Grown Control and Preinoculated Plants.

Root-associated bacteria were reisolated from surface-sterilized roots as described above using control and bacterially preinoculated plants harvested from both field plots in the 2013 field season (seven roots for each treatment from the Old field plot and three roots for each treatment from the New field plot). In the 2014 field season, the roots of five plants were analyzed when the plants had reached the early flowering stage. Bacterial plates were incubated at 28 °C for 4 d, and colonies were picked, subcultured, purified, and identified by 16S rDNA sequencing as described above.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Culture Conditions.

Wild-type N. attenuata Torr. Ex S. Watson seeds of the “Utah” ecotype were collected originally from a population at the DI (Desert Inn, 37.3267N, 113.9647W) ranch in Utah in 1989. For all in vitro and field experiments, wild-type seeds of the 31st inbred generation were surface sterilized and germinated on Gamborg’s B5 plates (Duchefa) as previously described (51). Seeds of the “Arizona” ecotype were used in the 22nd inbred generation.

Isolation of Bacteria and Fungi from Field-Grown Plants.

Field-grown N. attenuata plants at rosette and elongated stages that displayed symptoms of the sudden wilt disease were used for the isolation of potential plant pathogenic bacteria as described in ref. 12. Isolation of potential pathogenic fungi was carried out as described in ref. 13. Identification of bacterial and fungal isolates was performed as previously described (13, 14). The reisolation of the preinoculated bacteria was performed likewise using surface-sterilized roots of healthy plants to enrich endophytic bacteria. For detailed information, see SI Materials and Methods.

Plant Treatments in the Field.

Field experiments were conducted at a field station at the Lytle Ranch Preserve in Utah. For the 2013 field season, seeds were inoculated with the mixed bacterial solution (Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus E46, Bacillus cereus CN2, Bacillus megaterium B55, Bacillus mojavensis K1, Pseudomonas azotoformans A70, and Pseudomonas frederiksbergensis A176) or two native fungal isolates (Chaetomium sp. C72 and Oidodendron sp. Oi3). For the fungicide treatment, Jiffy pots (Jiffy 703, jiffygroup.com) were soaked with 15 mL of 1% fungicide solution (Landor; Syngenta) one night before planting. For the charcoal treatment, ∼100 g of charcoal was added to the soil surrounding each plant before planting. For the combined treatment the charcoal was presoaked with 25 mL of 5% fungicide solution (Landor; Syngenta). Size-matched plants of each treatment group were planted in a randomized design (735 on the Old plot and 261 on the New plot). For the repeated fungicide (fungicide 5×) treatment, plants were watered weekly with 50 mL of 1% fungicide solution. For the 2014 field season, bacterial consortia consisting of two (B55 + A70), three (K1 + A176 + E46), or five (K1 + A176 + E46 + B55 + A70) bacteria were used for seed inoculation, and 180 plants from the different treatments were planted into the Old plot. See SI Materials and Methods for additional experimental details; Table S1 lists the 32 ecological traits used to characterize bacterially inoculated plants planted into the New plot.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers.

The sequencing data for LK020799–LK021108 and LN556288–LN556387 have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive and KR906683–KR906715 in The National Center for Biotechnology Information. Also see Dataset S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brigham Young University for the use of the Lytle Preserve field station; the Utah field crew of 2013 and 2014, especially Pia Backmann, for field work; Danny Kessler and Martin Niebergall for providing and formatting the field-planting movie; and Stefan Meldau for acquiring the fungicide. This study was funded by the Max Planck Society, by Advanced Grant 293926 from the European Research Council, and by Global Research Lab Program Grant 2012055546 from the National Research Foundation of Korea, and by the Leibniz Association.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Sequences for LK020799–LK021108 and LN556288–LN556387 have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive database and KR906683–KR906715 in The National Center for Biotechnology Information.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1505765112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McFall-Ngai M, et al. Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(9):3229–3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218525110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundberg DS, et al. Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature. 2012;488(7409):86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanage WP. Microbiology: Microbiome science needs a healthy dose of scepticism. Nature. 2014;512(7514):247–248. doi: 10.1038/512247a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulgarelli D, et al. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature. 2012;488(7409):91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature11336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berendsen RL, Pieterse CMJ, Bakker PAHM. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17(8):478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glick BR. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: Mechanisms and applications. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012;2012:963401. doi: 10.6064/2012/963401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pieterse CMJ, et al. Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2014;52(1):347–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloepper J, Ryu C-M. 2006. Bacterial endophytes as elicitors of induced systemic resistance. Microbial Root Endophytes, SE-3, Soil Biology, eds Schulz BE, Boyle CC, Sieber T (Springer, Berlin), pp 33–52.

- 9.Weller DM, Raaijmakers JM, Gardener BBM, Thomashow LS. Microbial populations responsible for specific soil suppressiveness to plant pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2002;40(1):309–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.030402.110010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldwin IT. An ecologically motivated analysis of plant-herbivore interactions in native tobacco. Plant Physiol. 2001;127(4):1449–1458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long HH, Schmidt DD, Baldwin IT. Native bacterial endophytes promote host growth in a species-specific manner; phytohormone manipulations do not result in common growth responses. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long HH, Sonntag DG, Schmidt DD, Baldwin IT. The structure of the culturable root bacterial endophyte community of Nicotiana attenuata is organized by soil composition and host plant ethylene production and perception. New Phytol. 2010;185(2):554–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuck S, Weinhold A, Luu VT, Baldwin IT. Isolating fungal pathogens from a dynamic disease outbreak in a native plant population to establish plant-pathogen bioassays for the ecological model plant Nicotiana attenuata. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santhanam R, Groten K, Meldau DG, Baldwin IT. Analysis of plant-bacteria interactions in their native habitat: Bacterial communities associated with wild tobacco are independent of endogenous jasmonic acid levels and developmental stages. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meldau DG, Long HH, Baldwin IT. A native plant growth promoting bacterium, Bacillus sp. B55, rescues growth performance of an ethylene-insensitive plant genotype in nature. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3(June):112. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schippers B, Bakker AW, Bakker PAHM. Interactions of deleterious and beneficial rhizosphere microorganisms and the effect of cropping practices. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1987;25(1):339–358. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oyarzun P, Gerlagh M, Hoogland AE. Relation between cropping frequency of peas and other legumes and foot and root rot in peas. Neth J Plant Pathol. 1993;99(1):35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curl EA. Control of plant diseases. Bot Rev. 1963;29(4):413–479. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krupinsky JM, Bailey KL, McMullen MP, Gossen BD, Turkington TK. 2002. Managing plant disease risk in diversified cropping systems. Agron J 94(2):198–209.

- 20.Katawczik M, Mila AL. Plant age and strain of Ralstonia solanacearum affect the expression of tobacco cultivars to Granville wilt. Tob Sci. 2012;49:8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bull CT, et al. Letter to the editor list of new names of plant pathogenic bacteria (2008-2010) Prepared by the International Society of Plant Pathology Committee on the Taxonomy of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria (ISPP-CTPPB) J Plant Pathol. 2012;94(1):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larkin RP, Fravel DR. Efficacy of various fungal and bacterial biocontrol organisms for control of Fusarium wilt of tomato. Plant Dis. 2001;82(9):1022–1028. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.9.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, et al. Biocontrol of tomato wilt disease by Bacillus subtilis isolates from natural environments depends on conserved genes mediating biofilm formation. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15(3):848–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stockwell CA, Hendry AP, Kinnison MT. How does biodiversity influence the ecology of infectious disease? Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18(2):94–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuman MC, Heinzel N, Gaquerel E, Svatos A, Baldwin IT. Polymorphism in jasmonate signaling partially accounts for the variety of volatiles produced by Nicotiana attenuata plants in a native population. New Phytol. 2009;183(4):1134–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler D, et al. Unpredictability of nectar nicotine promotes outcrossing by hummingbirds in Nicotiana attenuata. Plant J. 2012;71(4):529–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Compant S, Duffy B, Nowak J, Clément C, Barka EA. Use of plant growth-promoting bacteria for biocontrol of plant diseases: Principles, mechanisms of action, and future prospects. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(9):4951–4959. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.4951-4959.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gindrat D, Gordon-Lennox G, Walther D, Jermini M. 1992. Biocontrol of sugarbeet damping-off with Chaetomium globosum: Promises and questions. Biological Control of Plant Diseases, SE - 26, NATO Advanced Science Institute Series, eds Tjamos EC, Papavizas GC, Cook RJ (Springer, New York), pp 197–201.

- 29.Alexander BJR, Stewart A. Glasshouse screening for biological control agents of Phytophthora cactorum on apple (Malus domestica) N Z J Crop Hortic Sci. 2001;29(3):159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santhanam R, Baldwin IT, Groten K. 2015. In wild tobacco, Nicotiana attenuata, variation among bacterial communities of isogenic plants is mainly shaped by the local soil microbiota independently of the plants’ capacity to produce jasmonic acid. Commun Integr Biol 8(2):e1017160.

- 31.Compant S, Clément C, Sessitsch A. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in the rhizo- and endosphere of plants: Their role, colonization, mechanisms involved and prospects for utilization. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42(5):669–678. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lugtenberg B, Kamilova F. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63(c):541–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Köberl M, et al. Bacillus and Streptomyces were selected as broad-spectrum antagonists against soilborne pathogens from arid areas in Egypt. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013;342(2):168–178. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tonelli ML, Taurian T, Ibáñez F, Angelini J, Fabra A. Selection and in vitro characterization of biocontrol agents with potential to protect peanut plants against fungal pathogens. J Plant Pathol. 2010;92(1):73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehmann J, et al. Biochar effects on soil biota – A review. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43(9):1812–1836. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sohi SP. 2012. Carbon storage with benefits. Science 338(6110):1034–1035.

- 37.Jetiyanon K, Kloepper JW. Mixtures of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for induction of systemic resistance against multiple plant diseases. Biol Control. 2002;24(3):285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niu D-D, et al. The plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Bacillus cereus AR156 induces systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana by simultaneously activating salicylate- and jasmonate/ethylene-dependent signaling pathways. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2011;24(5):533–542. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-10-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lugtenberg BJJ, Dekkers L, Bloemberg GV. Molecular determinants of rhizosphere colonization by Pseudomonas. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2001;39(1):461–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.39.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doornbos RF, Loon LC, Bakker PAHM. Impact of root exudates and plant defense signaling on bacterial communities in the rhizosphere. Agron Sustain Dev. 2011;32(1):227–243. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Figueiredo M, Seldin L, Araujo F, Mariano R. 2011. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: Fundamentals and applications. Plant Growth and Health Promoting Bacteria, SE-2, Microbiology Monographs, ed Maheshwari DK (Springer, Berlin), pp 21–43.

- 42.Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, Ver Loren van Themaat E, Schulze-Lefert P. 2012. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64:807–832. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Newton AC, Fitt BDL, Atkins SD, Walters DR, Daniell TJ. Pathogenesis, parasitism and mutualism in the trophic space of microbe-plant interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18(8):365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaiero JR, et al. Inside the root microbiome: Bacterial root endophytes and plant growth promotion. Am J Bot. 2013;100(9):1738–1750. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudrappa T, Czymmek KJ, Paré PW, Bais HP. Root-secreted malic acid recruits beneficial soil bacteria. Plant Physiol. 2008;148(3):1547–1556. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.127613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neal AL, Ahmad S, Gordon-Weeks R, Ton J. Benzoxazinoids in root exudates of maize attract Pseudomonas putida to the rhizosphere. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meldau DG, et al. Dimethyl disulfide produced by the naturally associated bacterium bacillus sp B55 promotes Nicotiana attenuata growth by enhancing sulfur nutrition. Plant Cell. 2013;25(7):2731–2747. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.114744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bakker M, Manter D, Sheflin A, Weir T, Vivanco J. Harnessing the rhizosphere microbiome through plant breeding and agricultural management. Plant Soil. 2012;360(1-2):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bulgarelli D, et al. Structure and function of the bacterial root microbiota in wild and domesticated barley. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(3):392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charlop-Powers Z, Owen JG, Reddy BVB, Ternei MA, Brady SF. Chemical-biogeographic survey of secondary metabolism in soil. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(10):3757–3762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318021111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krügel T, Lim M, Gase K, Halitschke R, Baldwin IT. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Nicotiana attenuata, a model ecological expression system. Chemoecology. 2002;12(4):177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelman A. The relationship of pathogenicity in Pseudomonas solanacearum to colony appearance on a tetrazolium medium. Phytopathology. 1954;44(12):693–695. [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Nakeeb MA, Lechevalier HA. Selective isolation of aerobic Actinomycetes. Appl Microbiol. 1963;11(July):75–77. doi: 10.1128/am.11.2.75-77.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diezel C, von Dahl CC, Gaquerel E, Baldwin IT. Different lepidopteran elicitors account for cross-talk in herbivory-induced phytohormone signaling. Plant Physiol. 2009;150(3):1576–1586. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.139550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schuman MC, Barthel K, Baldwin IT. Herbivory-induced volatiles function as defenses increasing fitness of the native plant Nicotiana attenuata in nature. eLife. 2012 doi: 10.7554/eLife.00007. 1:e00007. Available at dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.00007. Accessed August 15, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kallenbach M, et al. A robust, simple, high-throughput technique for time-resolved plant volatile analysis in field experiments. Plant J. 2014;78(6):1060–1072. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu J, Baldwin IT. New insights into plant responses to the attack from insect herbivores. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44(1):1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steppuhn A, Gase K, Krock B, Halitschke R, Baldwin IT. Nicotine’s defensive function in nature. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(8):E217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heiling S, et al. Jasmonate and ppHsystemin regulate key Malonylation steps in the biosynthesis of 17-Hydroxygeranyllinalool Diterpene Glycosides, an abundant and effective direct defense against herbivores in Nicotiana attenuata. Plant Cell. 2010;22(1):273–292. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.071449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oh Y, Baldwin IT, Gális I. NaJAZh regulates a subset of defense responses against herbivores and spontaneous leaf necrosis in Nicotiana attenuata plants. Plant Physiol. 2012;159(2):769–788. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.193771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.