Abstract

An extracellular β-agarase was purified from Pseudoalteromonas sp. NJ21, a Psychrophilic agar-degrading bacterium isolated from Antarctic Prydz Bay sediments. The purified agarase (Aga21) revealed a single band on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, with an apparent molecular weight of 80 kDa. The optimum pH and temperature of the agarase were 8.0 and 30 °C, respectively. However, it maintained as much as 85% of the maximum activities at 10 °C. Significant activation of the agarase was observed in the presence of Mg2+, Mn2+, K+; Ca2+, Na+, Ba2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Fe2+, Sr2+ and EDTA inhibited the enzyme activity. The enzymatic hydrolyzed product of agar was characterized as neoagarobiose. Furthermore, this work is the first evidence of cold-adapted agarase in Antarctic psychrophilic bacteria and these results indicate the potential for the Antarctic agarase as a catalyst in medicine, food and cosmetic industries.

Keywords: psychrophilic bacteria, cold-adapted agarase, purification, characterization

Introduction

Agar, an important polysaccharide derived from red algal (Gelidium and Gracilaria) cell walls, comprises agarose and agaropectin. Agarose is a linear chain consisting of alternating residues of 3-O-linked β-D-galactopyranose and 4-O-linked 3,6-anhydro-α-L-galactose (Duckworth and Yaphe, 1972). Agarase, a glycoside hydrolase (GH), can hydrolyze agarose. Based on the pattern of hydrolysis of the substrates, agarases are grouped into α-agarases and β-agarases (Araki, 1959; Hassairi et al., 2001). α-Agarases cleave the α-1,3 linkages to produce a series of agarooligosaccharides related to agarobiose (Potin et al., 1993), whereas β-agarases cleave the β-1,4 linkages to produce a series of neoagarooligosaccharides related to neoagarobiose (Kirimura et al., 1999). Most of the reported agarases are β-agarases, which are classified into four glycoside hydrolase (GH) families, GH16, GH50, GH86, and GH118, based on the amino acid sequence similarity on the Carbohydrate-Active EnZyme database (CAZy) (Cantarel et al., 2009; Chi et al., 2012). To date, most of the agarases have been isolated from various sources, including seawater, marine sediments, marine algae, marine mollusks, fresh water, and soil(Fu and Kim, 2010); however, agarases isolated from the Antarctic environment have not yet been reported.

The Antarctic marine environment is perennially cold, and in some cases, it is permanently covered with ice. Spatial heterogeneity, combined with extreme seasonal fluctuations such as those experienced during the annual sea-ice formation events, results in a high diversity of microbial habitats and, therefore, microbial communities (Karl, 1993). Extreme environments are proving to be a valuable source of microorganisms that secrete interesting novel molecules, including enzymes, lipids, exopolysaccharides, and other active substances. The enzymes produced by psychrophilic and psychrotrophic microorganisms with unique physiological and biochemical characteristics have significant advantages in some areas in comparison to the enzymes from mesophiles (Chintalapati et al., 2004; Garcia-Viloca et al., 2004; Georlette et al., 2013). These cold-adapted enzymes are important biocatalysts for various industrial applications due to their high catalytic activity at low temperatures and low thermostability (D’Amico et al., 2003; Siddiqui and Cavicchioli, 2006). Until recently, agarases produced by Antarctic microorganisms were an unknown entity. In this paper, a new exo-β-agarase Aga21 from an Antarctic psychrophilic strain was isolated and identified as Pseudoalteromonas sp. After the enzyme was purified, its characteristics in terms of enzyme activity were analyzed under different temperature and pH conditions. This study is the first to report on a cold-adapted agarase derived from the Antarctic psychrophilic strain.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and identification of agarase-producing bacterial strain

The agarase-producing psychrophilic strain was isolated from sediments collected from Antarctic Prydz bay (75°45.9′E; 68°5.65′S). The strain was inoculated on a 2216E medium containing 0.5% (w/v) peptone, 0.1% (w/v) yeast extract and 2.0% (w/v) agar, and incubated at 10 °C. After being cultured for 24 h on 2216E, the strain was inoculated on selection plates containing agar as the sole source of energy and carbon; positive colonies showing clear zones or pits were selected.

The chromosomal DNA of the agarase-producing strain was extracted using the DNA Extraction Kit (TianGen, Biotech CO., LTD., Beijing, China). Using the chromosomal DNA as the template, the 16S rRNA was PCR amplified with primers 27F and 1492R, and the PCR products were sequenced by Shanghai Sunny Biotechnology Co, Ltd.

Purification of agarase

To isolate agarase, the agarase-producing strain was grown in 500 mL vials containing 300 mL of the 2216E liquid medium supplemented with 0.3% agarose and incubated at 10 °C. The culture supernatant separated from bacteria grown for 56 h were obtained via centrifugation at 6000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Solid ammonium sulfate was added to the crude enzyme solution to 70% saturation with slow stirring for 1 h. The precipitate was dissolved in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) and dialyzed against 1000 mL of the same buffer overnight with intermittent change of buffer every 4 h. The dialyzed sample was concentrated with a polyethylene glycol 20,000 solution.

The crude enzyme solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm filter membrane to remove any undissolved substances. The concentrated crude enzyme solution was then applied onto a Q-Sepharose F.F. column (2.6 × 40 cm) equilibrated with sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5). The column was washed with 50 mL of the same buffer to remove the unbound proteins. The enzyme was eluted in 1.5 mL fractions by a discontinuous gradient of NaCl (0–0.5 M) in the same buffer. The fractions with the highest enzyme activities were pooled and further purified via gel filtration on a Sephacryl S-200 column using the same buffer. The active fractions were analyzed for protein content by reading the absorbance at 280 nm and stored at 4 °C until further use. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out to estimate the protein molecular weight with a stacking gel (4% polyacrylamide) and a separating gel (10% polyacrylamide).

Agarase enzyme assay

The specific activity of the purified Aga21 was determined according to a modified method developed by Ohta et al. (2005). Appropriately diluted enzyme solution was added to different substrates in Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and incubated at 40 °C for 30 min. The activity was expressed as the initial rate of agar hydrolysis by measuring the release of reducing ends using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) procedure with D-galactose as the standard (Miller, 1959). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that can catalyze the production of 1 μmol of reducing sugar (in the present study, D-galactose) per minute.

Effect of pH, temperature, and additives

In each experiment, 1.0% agar solution and purified agarase were mixed and incubated at various durations and temperatures. The relative agarase activity was determined using the DNS method. The optimum temperature of Aga21 activity was determined by monitoring the relative enzymatic activity at temperatures ranging from 10 °C to 60 °C at pH 8.0. The optimum pH was tested at a pH range of 3.5–10.0 with pH intervals of 0.5 at 40 °C. HAc-NaAc buffer, KH2PO4-NaOH buffer, Tris-HCl buffer, and NaCO3-NaHCO3 buffer were used to achieve pH 3.5–6.0, pH 6.0–7.0, pH 7.0–9.0, and pH 9.0–10.0, respectively. The thermostability of Aga21 was evaluated by measuring the residual activity of the enzyme after incubation at a temperature range of 10–50 °C for 30, 60, and 180 min. The effects of various metal ion salts and chelator on the purified Aga21 activity were tested by determining the enzyme activity in the presence of various ions or chelator (CaCl2, CuSO4, FeSO4, KCl, MgSO4, MnCl2, NaCl, and EDTA) at a final concentration of 2 mmol/L, incubated at 40 °C for 30 min. The assay mixture without the addition of metal ion salts or chelator was used as the control.

Identification of Aga21-hydrolyzed agar products

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was used to identify the hydrolysis products of agar. Neoagarodecaose (NA10), neoagarooctaose (NA8), neoagarotetraose (NA4), and neoagarobiose (NA2) were purchased from Sigma. The reaction of purified Aga21 and agar was carried out in 100-mL tubes containing 10 mL of purified Aga21 (24 units/mL) and 90 mL of 1.0% agar at 40 °C for 30, 60, and 120 min. Subsequently, the reaction mixtures were applied to a silica gel 60 TLC plate (Merck, Germany). The TLC plates were developed using a solvent system consisting of n-butanol, acetic acid, and water (2:1:1, v/v). After hydrolysis of the substrates, the resultant oligosaccharide spots were visualized by spraying 10% H2SO4 on the TLC plate and then heating it on a hot plate.

Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

After enzymatic hydrolysis, the oligomers were precipitated with iso-propanol and dried at room temperature. The dried material was dissolved in D2O for 13C NMR spectroscopy. The NMR spectrum was recorded on Varian Inova 600 at room temperature.

Results

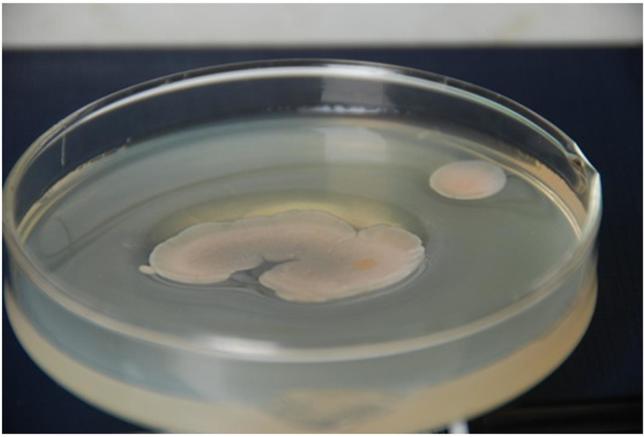

Isolation and identification of strain NJ21

Initially, the agarase-producing Antarctic psychrophilic strain was isolated from the selection plates showing a clear hydrolysis pit (Figure 1). The 16S rRNA sequence analysis results showed that the isolated bacterium from the sediment samples was 99% similar to Pseudoalteromonas sp. And, hence, was assigned to the genus Pseudoalteromonas and named Pseudoalteromonas sp. NJ21 (GenBank accession number: KF700697). The pure strains are conserved in the key Laboratory of Marine Bio-active Substances SOA.

Figure 1. Colonies of Pseudoalteromonas sp. NJ21 on an agar plate showing deep pits around them.

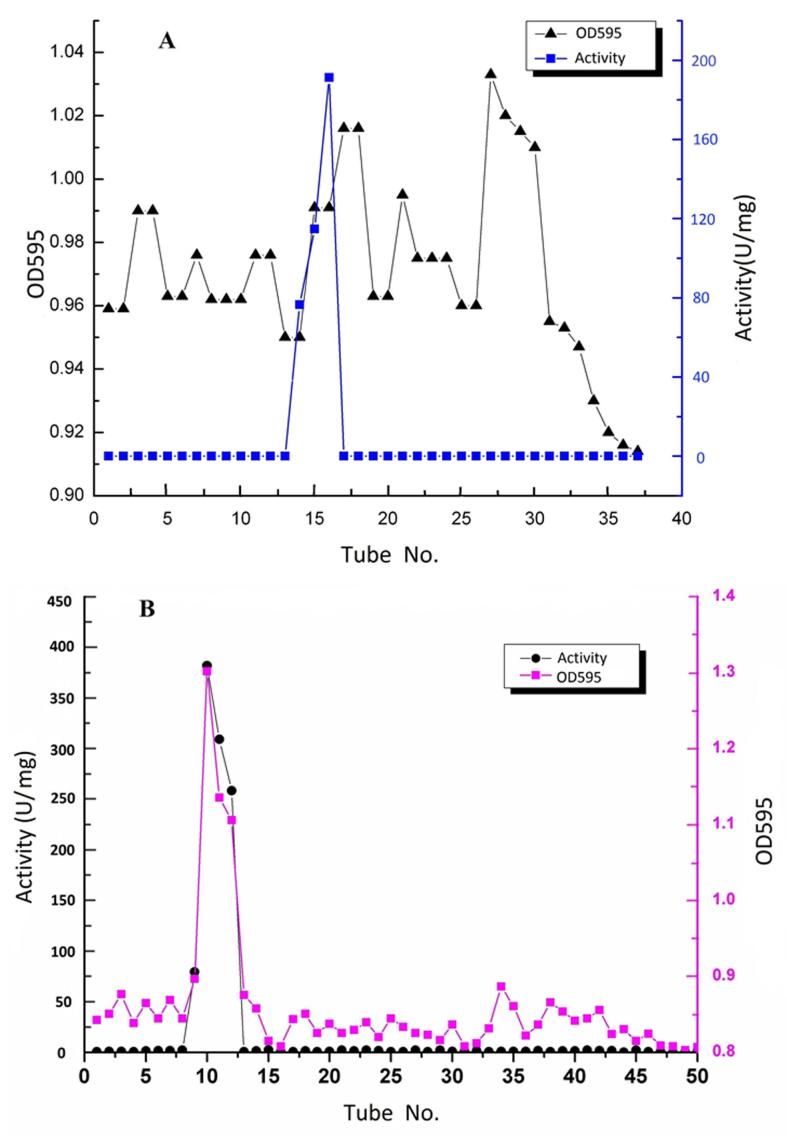

Separation and purification of Aga21

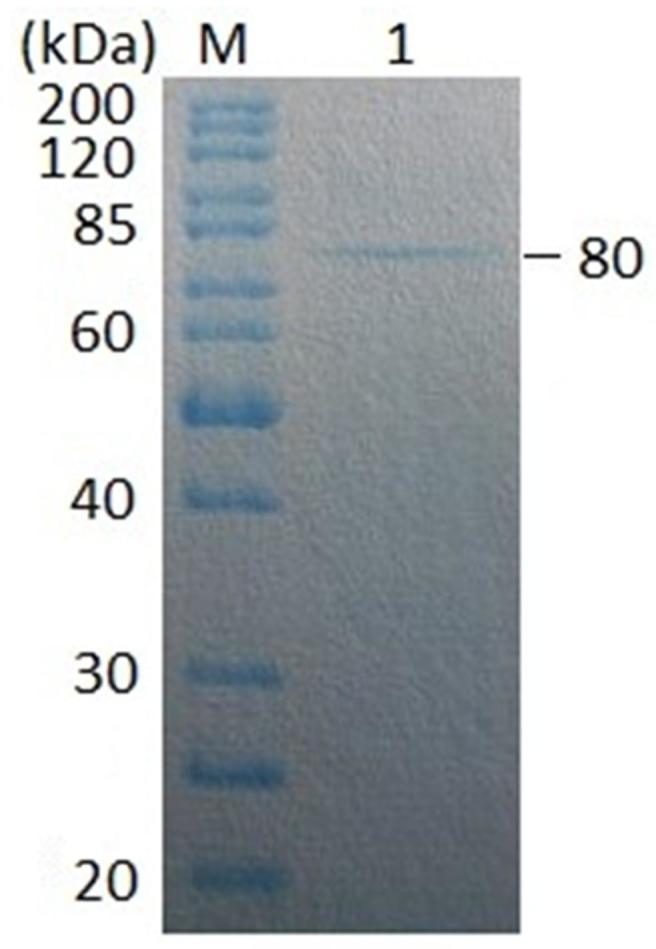

The Aga21 was purified via ammonium sulfate fractionation followed by a combination of two chromatographic steps (Figure 2). The Aga21 was purified 47.78-fold with a specific activity of 373.62 U/mg and a final yield of 10.68% (Table 1). SDS-PAGE revealed the presence of a single protein band with agarase activity, whose apparent molecular weight was estimated to be 80 kDa (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Purification via anionic exchange chromatography (A) and gel chromatography (B) of the Aga21.

Table 1. Summary of the purification of Aga21.

| Steps | Total activity (U) | Total protein (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Purification (fold) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture supernatant | 2865 | 366.25 | 7.82 | 1 | 100 |

| (NH4)2SO4precipitation | 426.73 | 285 | 32.84 | 4.19 | 14.89 |

| Q-Sepharose F.F | 305.91 | 1.74 | 175.93 | 22.49 | 10.68 |

| Sephacryl S-200HR | 211.84 | 0.57 | 373.62 | 47.78 | 7.40 |

Figure 3. Electrogram of SDS-PAGE of the purified Aga21.

Influence of pH and temperature on enzyme activity and stability

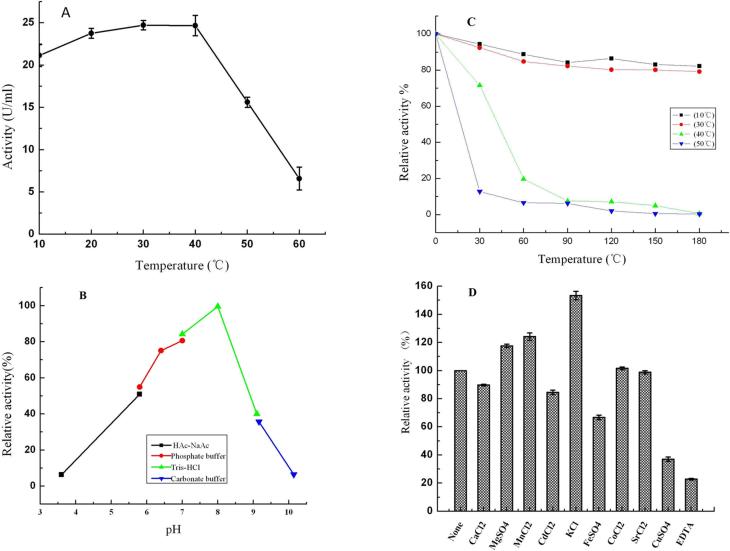

Although the optimum reaction temperature of the purified Aga21 was 30 °C (Figure 4A), as much as 85% of the maximum activity was observed at 10 °C. The effect of pH on the purified enzyme is shown in Figure 4B. The maximum enzyme activity was observed at pH 8.0, and the enzyme was stable (> 70% relative activity) in buffers with a pH range of 6.5–8.5 under the assay conditions. The temperature dependence of the Aga21 activity on agar was determined by measuring the enzyme activity at various temperatures for 180 min. The effect of temperature on the stability of Aga21 is shown in Figure 4C. Up to 80% thermostability of Aga21 was retained at 10 °C and 30 °C for 180 min. However, when the temperature was increased to 50 °C for 30 min, the enzyme relative activity was decreased to 10–20%. Nevertheless, the enzyme was fairly stable (almost 70% relative activity) at 40 °C for 30 min.

Figure 4. Biochemical characterization of pure Aga21 describing the effect of (A) temperature, (B) pH, (C) thermostability and (D) various additives. Note: the definition of relative activity of figures A, B and C were as follow: The maximum enzyme activity was defined as 100%, the relative activity = the actual enzyme activity/the maximum enzyme activity × 100%. The definition of relative activity of figure D was as follow: The enzyme activity of control group (no additive) was defined as 100%, the relative activity = the treatment group enzyme activity/the control group enzyme activity × 100%.

Effect of various additives

The effect of metal ion salts and chelators on the activity of purified Aga21 is shown in Figure 4D. Divalent metal salts such as CuSO4, CdCl2, FeSO4, and CaCl2 (each at 2 mM final concentration) completely inhibited the relative activity of Aga21, whereas 2 mM EDTA inhibited 60% of the enzyme activity. In contrast, 2 mM KCl, MnCl2, and MgSO4 enhanced the activity of Aga21 compared to the other metal ion salts.

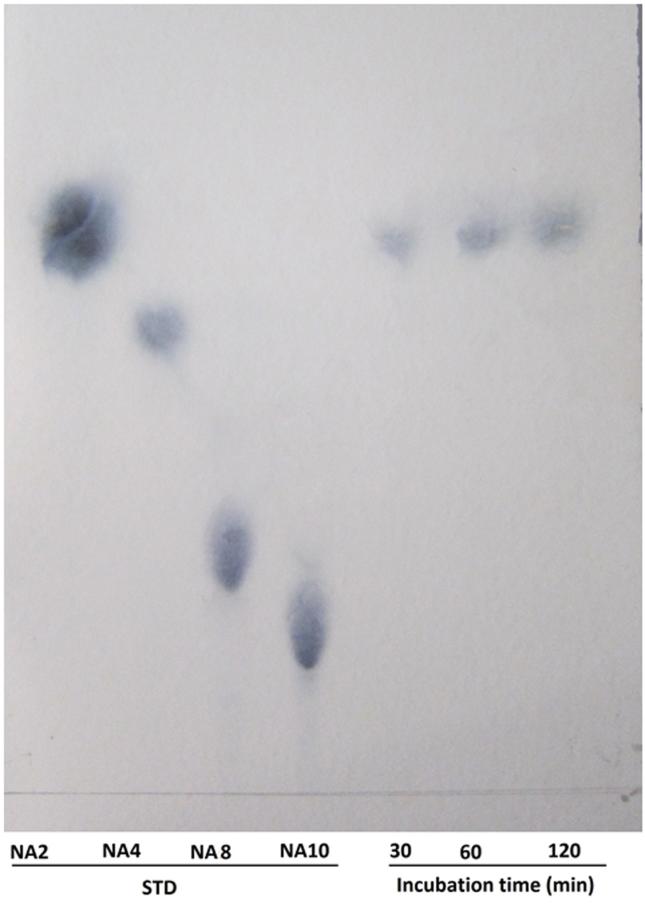

Identification of the hydrolysis products of Aga21

The hydrolysis patterns of the purified Aga21 against food-grade agar are shown in Figure 5. The agarooligosaccharides, which were purchased by Sigma, were also run along with the agarose hydrolyzed products by Aga21 on TLC. None of the agar hydrolysis products produced by the purified Aga21 matched the Rf values of agarooligosaccharides (data not shown), whereas the Rf values did match with the standard neoagarooligosaccharides. When Aga21 was incubated with agar, only one distinct spot, NA2, was observed on the TLC plates at 30, 60, and 120 min after the reaction.

Figure 5. Thin-layer chromatogram of the hydrolysis products of purified Aga21 reaction NA2, neoagarobiose; NA4, neoagarotetraose; NA8, neoagarooctaose; NA10, neoagarodecaose.

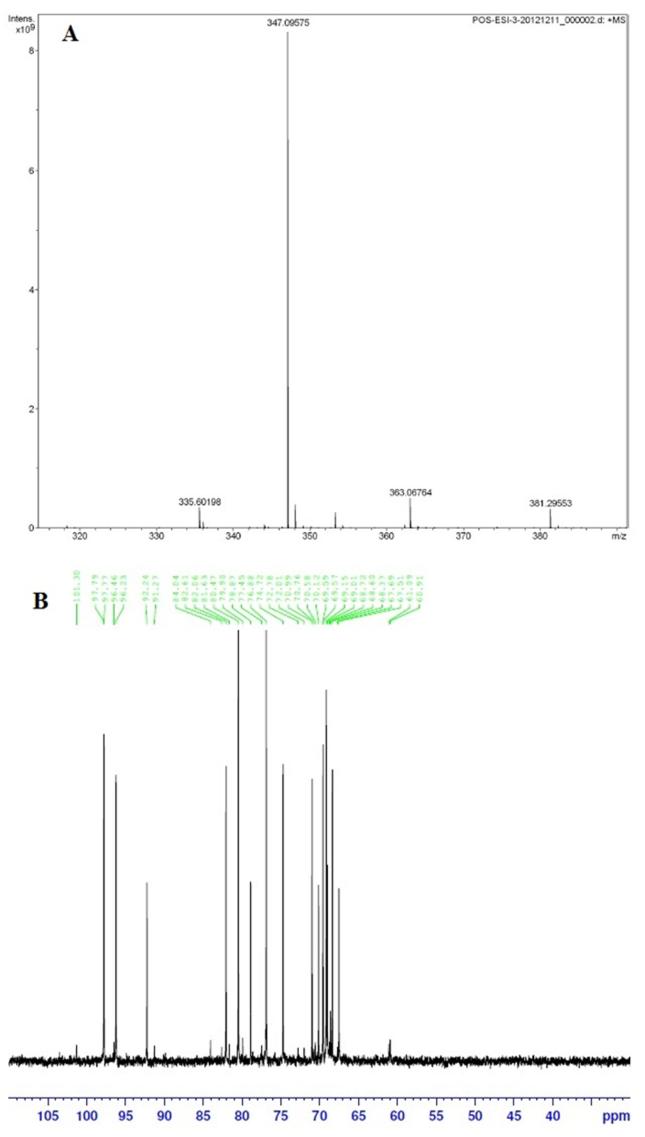

Further, the predicted molecular mass of deprotonated disaccharide showed a peak at 347.3 [M+Na]+ after LC-MS analysis (Figure 6A). The MW of 324.3 Da corresponds to the disaccharide unit neoagarobiose (C12H20O10) with formula weight of 324.28 indicative of the β-cleavage. The β-cleavage of agar was further confirmed with 13C NMR spectroscopy. The NMR result showed typical resonance signals at 102 and 98 ppm, which matched the reducing end of neoagarobiose (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Analysis of agar hydrolyzed products based upon LC- mass spectroscopy (A) and 13C NMR spectroscopy (B).

Discussion

An increasing number of research programs are being sponsored to examine the enzymes produced by microorganisms isolated from Antarctica, some of which may have commercial potential. Examples of the enzymes identified from these studies include α-amylase (used in bread-making, textiles, brewing, and detergents), cellulase (used in textiles and pulp and paper industries), β-galactosidase (which eliminates lactose from milk), lipase (used in detergents and flavorings), proteases (used in detergents and for tenderizing meat), and xylanase (used in bread-making) (Gerday et al., 2000). However, to date, studies of agarases from Antarctic microorganisms have not yet been reported. In the present study, a newly found agarase-producing Antarctic psychrophilic bacterial isolate was assigned to the genus Pseudoalteromonas based on the 16S rDNA sequence analysis. Earlier, mesophilic agarolytic microorganisms were discovered in marine habitats, where marine red algae could be the source of agar as a substrate for them. However, the data demonstrate that agarolytic prokaryotes can also live when a polysaccharide of cyanobacteria forming cyanobacterial mats (Namsaraev et al., 2006) is the substrate for agarase. Because there are many cyanobacteria in the Antarctic Ocean, the polysaccharide of cyanobacteria may be the substrate for agarolytic Antarctic bacteria.

The reported molecular weight of agarase varies from values as low as 12 kDa (Khambhaty et al., 2008), in the case of B. megaterium, to as high as 210 kDa, in the case of Pseudomonas-like bacteria (Malmqvist, 1978). β-agarases are classified into three groups by their molecular weights: Group I (20–49 kDa), Group II (50–80 kDa), and Group III (> 60 kDa) (Leon et al., 1992). The result of SDS-PAGE of purified Aga21 revealed a molecular mass of 80 kDa and may belong to group III β-agarases.

Temperature and pH are considered to be decisive parameters for enzyme activity. It was observed that the activity of Aga21 consistently increased from 10 to 40 °C, with optimum activity at 30 °C. However, a drastic decrease was observed when the Aga21 was incubated at temperatures above 40 °C. The activity of Aga21 was stable at a low temperature and retained more than 85% of its activity at a temperature of 10–30 °C, which is lower than many other agarases (Kirimura et al., 1999; Ohta et al., 2005; Vander Meulen and Harder, 1975). Temperature optima of various agarases are higher than the gelling temperature of agar because compact bundles of gelled agar hinder enzyme action (Jonnadula and Ghadi, 2011; Ohta et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2003; Vander Meulen and Harder, 1975). However, the agarase Aga21 can efficiently liquefy solid agar at a temperature of 10 °C. When compared with the other agarases, the Aga21 had a comparatively lower optimum temperature and very low temperature tolerance as a cold-adapted enzyme. This unique characteristic may be useful for preparing protoplasts and extracting biological substances from algae at low temperatures. The enzyme exhibited the maximum agarase activity at pH 8.0, whereas the optimum pH for many other agarases is 7.0 (Jonnadula and Ghadi, 2011; Long et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2008). Other agarases active in alkaline pH have been reported (Fu and Kim, 2010). Aga21 was stable in a wide pH range of 6.5–8.5, retaining more than 70% of its residual activity, which was similar to those of some other agarases such as AgaY (6.0–8.0) (Shi et al., 2008) and that from Bacillus sp. MK03 (7.1–8.2) (Suzuki et al., 2003). As observed with other β-agarases, KCl, MgSO4, and MnCl2 acted positively on the activity of the Aga21, which is consistent with the fact that V134, the source strain of AgaV, is a marine inhabitant. However, CaCl2 exhibited no apparent effect on the activity of the enzyme at 2 mM concentrations, which is in contrast to the observations of the β-agarase AgaO and AgaB of the Pseudoalteromonas sp. reported by Ohta et al. (2004a) and Ma et al. (2007), who found that CaCl2stabilizes the activity of AgaO and enhances the activity of AgaB. Similar to other agarases, the activity of the agarase identified in the present study was strongly inhibited by EDTA and several reagents, particularly, heavy metal ions.

The β-agarases are known for their endo- and exolytic cleavage producing neoagarobiose and other intermediate products such as neoagarotetrose and neoagarohexose (Fu et al., 2008). The β-agarase from Alteromonas sp. (Wang et al., 2006) and the agarase Ag50D from S. degradans have exolytic cleavage modes that mainly produce the neoagarobiose (Kim et al., 2010). The agarase enzyme investigated in this study also yielded neoagarobiose as a major product indicating the exolytic cleavage of agar. 13C NMR analysis of oligosaccharides deduced that the agarase produced 3, 6-anhydrogalactose as the non-reducing end and galactose as the reducing end. This was also confirmed with LC-MS analysis. The abovementioned findings provide evidence that the enzyme investigated in this study is a β-agarase with exolytic cleavage of agar.

There are few bacteria (Aoki et al., 1990; Kong et al., 1997; Sugano et al., 1993; Araki et al., 1998) that are capable of producing β-agarases and can hydrolyze agarose and neoagaro-oligosaccharides to yield neoagarobiose. Neoagarobiose produces both moisturizing and whitening effects on skin (Kobayashi et al., 1997), and the agarase-degraded extract from a red seaweed, Gracilaria verrucosa, has been reported to increase the phagocytic activity of mice (Yoshizawa et al., 1996). Hence, the oligosaccharide extracts from agar or seaweeds hydrolyzed by the newly cold-adapted Aga21 may be a useful source to obtain physiologically functional products with antioxidative or immunopotentiating activities.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Public Science and Technology Research Funds Project of Ocean (201105027), Chinese Polar Environment Comprehensive Investigation & Assessment Programs (CHINARE2014-01-05), Shandong Province Young and Middle-Aged Scientists Research Awards Fund (BS2010HZ001), and Basic Scientific Research Funds of FIO, SOA (GY0214T09).

References

- Aoki T, Araki T, Kitamikado M. Purification and characterization of a novel beta-agarase from Vibrio sp. AP-2. Eur J Biochem. 1990;187:461–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki C. Seaweed polysaccharides. In: Wolfrom ML, editor. Carbohydrate chemistry of substances of biological interests. Pergamon Press; London: 1959. pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Araki T, Lu Z, Morishita T. Optimization of parameters for isolation of protoplasts from Gracilaria verrucosa (Rhodophyta) J Mar Biotechnol. 1998;6:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, et al. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZyme database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:233–238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi WJ, Chang YK, Hong SK. Agar degradation by microorganisms and agar-degrading enzymes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;94:917–930. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintalapati S, Kiran MD, Shivaji S. Role of membrane lipid fatty acids in cold adaptation. Cell Mol Biol. 2004;50:631–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico S, Gerday C, Feller G. Temperature adaptation of proteins: engineering mesophilic-like activity and stability in a cold-adapted a amylase. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth M, Yaphe W. In: Nisizawa K, editor. The relationship between structures and biological properties of agars; Proceedings of the 7th international seaweed symposium; New York: Halstead Press; 1972. pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fu XT, Kim SM. Agarase: Review of Major Sources, Categories, Purification Method, Enzyme Characteristics and Applications. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:200–218. doi: 10.3390/md8010200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XT, Lin H, Kim SW. Purification and characterization of a novel β-agarase, AgaA34, from Agarivorans albus YKW-34. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;78:265–273. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Viloca M, Gao J, Karplus M, et al. How enzymes work: analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science. 2004;303:186–195. doi: 10.1126/science.1088172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georlette D, Damien B, Blaise V, et al. Structural and functional adaptations to extreme temperatures in psychrophilic, mesophilic and thermophilic DNA ligases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37015–37023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerday C, Aittaleb M, Bentahir M, et al. Cold-adapted enzymes: from fundamentals to biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassairi I, Ben AR, Nonus M, et al. Production and separation of alpha-agarase from Altermonas agarlyticus strain GJ1B. Biores Technol. 2001;79:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(01)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonnadula R, Ghadi SC. Purification and characterization of β-agarase from seaweed decomposing bacterium Microbulbifer sp. strain CMC-5. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2011;16:513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Karl DM. Microbial processes in the Southern Ocean. In: Friedmann EI, editor. Antarctic Microbiology. New York: 1993. pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Khambhaty Y, Mody K, Jha B. Purification, characterization and application of a novel extracellular agarase from a marine Bacillus megaterium . Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2008;13:584–591. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HT, Lee S, Lee D, et al. Overexpression and molecular characterization of Aga50D from Saccharophagus degradans 2–40: an exo-type β-agarase producing neoagarobiose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86:227–234. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirimura K, Masuda N, Iwasaki Y, et al. Purification and characterization of a novel β-agarase from an alkalophilic bacterium, Alteromonas sp. E-1. J Biosci Bioeng. 1999;87:436–441. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(99)80091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi R, Takisada M, Suzuki T, et al. Neoagarobiose as a novel moisturizer with whitening effect. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:162–163. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong JY, Hwang SH, Kim BJ, et al. Cloning and expression of agarase gene from a marine bacterium Pseudomonas sp. W7. Biotechnol Lett. 1997;19:23–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1024586207392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon O, Quintana L, Peruzzo G, et al. Purification and properties of an extracellular agarase from Alteromonas sp. strain C-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:4060–4063. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.4060-4063.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M, Yu Z, Xu X. A novel beta-agarase with high pH stability from marine Agarivorans sp. LQ48. Mar Biotechnol. 2010;12:62–69. doi: 10.1007/s10126-009-9200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Lu X, Shi C, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel beta-agarase, AgaB, from marine Pseudoalteromonas sp. CY24. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3747–3754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist M. Purification and characterization of two different agarose degrading enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;537:31–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(78)90600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31:426–428. [Google Scholar]

- Namsaraev ZB, Gorlenko VM, Namsaraev BB, et al. Microbial Communities of Alkaline Hydrotherms. Novosibirsk, Russia: 2006. pp. 10–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta Y, Hatada Y, Ito S, et al. High-level expression of a neoagarobiose-producing beta-agarase gene from Agarivorans sp. JAMB-A11 in Bacillus subtilis and enzymic properties of the recombinant enzyme. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2005;41:183–191. doi: 10.1042/BA20040083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta Y, Hatada Y, Nogi Y, et al. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a glycoside hydrolase family 86 beta agarase from a deep-sea Microbulbifer-like isolate. Appl Microb Biotechnol. 2004a;66:266–275. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1757-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potin P, Richard C, Rochas C, et al. Purification and characterization of the α-agarase from Alteromonas agarlyticus (Cataldi) comb. nov., strain GJ1B. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YL, Lu XZ, Yu WG. A new β-agarase from marine bacterium Janthinobacteriumsp. SY12. WorldJ Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;24:2659–2664. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui KS, Cavicchioli R. Cold-adapted enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:403–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugano Y, Terada I, Arita M, et al. Purification and characterization of a new agarase from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. Strain JT0107. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1549–1554. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1549-1554.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Sawai Y, Suzuki T, et al. Purification and characterization of an extracellular β-agarase from Bacillus sp. MK03. J Biosci Bioeng. 2003;93:456–463. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(02)80092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Meulen HJ, Harder W. Production and characterization of the agarase of Cytophaga flevensis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1975;41:431–447. doi: 10.1007/BF02565087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jiang X, Mou H, et al. Anti-oxidation of agar oligosaccharides produced by agarase from a marine bacterium. J Appl Phycol. 2004;16:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Mou H, Jiang X, et al. Characterization of a novel β-agarase from marine Alteromonas sp. SY37–12 and its degrading products. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;71:833–839. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa Y, Tsunehiro J, Nomura K, et al. In vivo macrophage-stimulation activity of the enzyme-degraded water-soluble polysaccharide fraction from a marine alga (Gracilaria verrucosa) Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:1667–1671. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]