Abstract

Both cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout and antagonism produce well-established attenuation of palatable food and drug self-administration behavior. Although cannabinoid drugs have received attention as pharmacotherapeutics for various disorders, including obesity and addiction, it is unclear whether these agents produce equivalent behavioral effects in females and males. In this study, acquisition of 32% corn oil or 10% Ensure self-administration, and maintenance of corn oil, Ensure, or 0.56 mg/kg/infusion cocaine self-administration under both fixed ratio (FR)-1 and progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement, was compared in male and female wild type (WT) and CB1 knockout (KO) mice. Furthermore, the effect of pretreatment with the CB1 antagonist SR141716 (0.3–3.0) on Ensure self-administration in male and female WT and CB1 KO mice was assessed. CB1 genotype and sex significantly interacted to produce an attenuation of acquisition and maintenance of Ensure self-administration and PR self-administration for both Ensure and cocaine in male CB1 KO mice. In contrast, male CB1 KO mice showed no deficit in acquisition and maintenance of FR-1 responding or in PR responding maintained by corn oil. Sex differences also arose within genotypes for responding maintained under all three reinforcers. Lastly, pretreatment with SR141716 attenuated Ensure self-administration in WT and CB1 KO mice but was approximately five-fold more potent in WT mice than in CB1 KOs. The present data add to a small but growing literature suggesting that the cannabinoid system may be differentially sensitive in its modulation of appetitive behavior in males versus females.

Keywords: CB1 receptor, knockout, mouse, palatable food, self-administration, sex differences, SR141716

Introduction

The endogenous cannabinoid (CB) system has been implicated in a variety of physiological functions, including appetite and reward (see Solinas et al., 2003 for review). CB drugs are widely used recreationally and have received much interest recently as potential pharmacotherapeutics for the treatment of obesity (Vemuri et al., 2008) and addiction (Parolaro et al., 2005). Furthermore, although it has become clear within the last decade that many drugs do not produce equivalent behavioral effects in females and males, it is not yet known whether CB drugs produce consistently different effects in men and women (see Craft, 2005 for review). For example, although it is well-known that CBs found in Cannabis sativa (a.k.a. marijuana) can increase appetite, particularly for sweet and palatable foods (Abel, 1975; Foltin et al., 1988), whether sex differences exist in the appetite-stimulating effects of cannabis has not been systematically studied in humans. It has been reported, however, that men describe greater subjective effects of marijuana intoxication than women (Penetar et al., 2005). To date, two animal studies have compared behavioral effects of CB agonists in male versus female laboratory animals; Miller et al. (2004) reported that the CB agonist CP 55,940 was more potent in male than female rats in increasing intake of sweetened condensed milk, and similarly Diaz et al. (2009) reported that the CB agonist WIN 55212 produced more pronounced hyperphagia in male versus female guinea pigs with free access to laboratory chow. Taken together, these studies suggest that the CB1 receptor system may be preferentially involved in the regulation of appetite and reward in males versus females.

There is now a great deal of preclinical and clinical evidence that antagonism of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor system decreases motivation for palatable foods and drugs of abuse. For example, palatable food consumption and self-administration by laboratory animals are attenuated by antagonism of CB1 receptors (Arnone et al., 1997; Higgs et al., 2003; McLaughlin et al., 2003; Thornton-Jones et al., 2005; Ward and Dykstra, 2005), and the CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 (Rimonabant) produces weight loss in obese human subjects (Van Gaal et al., 2005, Pi-Sunyer et al., 2006), although its clinical utility has been compromised by the production of serious psychiatric side effects (Traynor et al., 2007). CB1 receptor antagonism also attenuates the reinforcing effects of several drugs of abuse in laboratory animals (see Le Foll and Goldberg, 2005 for review), increases rates of nicotine cessation in humans (Anthenelli and Despres, 2004), and is currently being investigated for its ability to reduce voluntary alcohol consumption by nontreatment-seeking heavy drinkers. Whether CB1 receptor antagonism is more potent at attenuating appetite and/or drug reward in males versus females remains relatively unexplored [but see Foltin and Haney (2007); Diaz et al., 2009].

Operant responding for palatable foods and addictive drugs is also altered in mice with a genetic invalidation of the CB1 receptor (CB1 KO) (Poncelet et al., 2003; Sanchis-Segura et al., 2004; Ward and Dykstra, 2005; see Le Foll and Goldberg, 2005 for review). More specifically, we have recently reported that male CB1 receptor knockout (KO) mice show significant deficits in responding for the sweet food reinforcer Ensure. However, these mice acquire self-administration of the pure fat reinforcer corn oil and will continue to respond for corn oil under both fixed ratio (FR) and progressive ratio (PR) schedules of reinforcement, and also fully reinstate corn-oil-seeking behavior after extinction (Ward and Dykstra, 2005; Ward et al., 2007). In addition, although initial studies showed that cocaine self-administration under an FR schedule was not impaired in CB1 KO mice (Cossu et al., 2001), Soria et al. (2005) showed significant deficits in CB1 KO mice self-administering cocaine under a PR schedule of reinforcement. Taking these results together with the previously mentioned sex difference studies, we hypothesized that male CB1 KO mice would show more robust impairments in sweet palatable food and cocaine self-administration behavior as compared with female CB1 KO mice. We also hypothesized that, as is the case with male CB1 KO mice, female CB1 KO mice would not show a significant impairment of corn oil self-administration. Lastly, we hypothesized that the CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 would produce more robust attenuation of self-administration behavior in males versus females. To test these hypotheses, acquisition of 32% corn oil or 10% Ensure self-administration and maintenance of corn oil, Ensure, or 0.56 mg/kg/infusion cocaine self-administration, under both an FR-1 and PR schedule of reinforcement, was compared in male and female wild type (WT) and CB1 KO mice. In addition, the effect of pretreatment with the CB1 antagonist SR141716 on Ensure self-administration in male and female WT and CB1 KO mice was assessed.

Methods

Subjects

Twenty male WT, 19 male CB1 KO, 17 female WT, and 21 female CB1 KO mice were used for these experiments. The CB1 knockout mice were generated on a full C57Bl/6 background by Zimmer et al. (1999) at the National Institutes of Health by a targeted mutation of the large single coding sequence of the CB1 receptor gene. Nucleic acids that code for amino acids 32 though 448 were replaced with a PGK-neo cassette through homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells (Zimmer, 1992). Heterozygous breeding pairs were obtained from a colony at Virginia Commonwealth University, and were bred and genotyped at Temple University to obtain male and female WT and CB1 KO knockout mice. After weaning and genotyping, all mice were singly housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with lights off at 07.00 h, so that all experimental testing occurred during the dark cycle of the animals’ diurnal cycle. During the acquisition phase of the study, animals were maintained at 90% of their free-feeding body weight (approximately 2.5 g daily Purina Rodent Chow Diet 5001, Ralston-Purina, St. Louis, Missouri, USA); after acquisition all mice were given free access to food and water throughout the duration of the operant studies. Animal protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee, and the methods were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (National Research Council 2003).

Apparatus

Food and cocaine self-administration experiments were conducted in mouse operant conditioning chambers (21.6 cm × 17.8 cm × 12.7 cm, Model ENV-307W, Med Associates, Georgia, Vermont, USA) located within ventilated sound attenuation chambers. The operant conditioning chambers were equipped with two nose-poke holes (1.2 cm diameter) with internal amber stimulus lights (ENV-313W), a house light (ENV-315M), ventilator fan, tone generator (ENV-323AW), and motor-driven dippers (ENV-302W) for liquid food presentation. The receptacle opening for access to the food was located between the two nose-poke holes, and an amber stimulus light was located above the receptacle opening (ENV-221M). For cocaine experiments, drug delivery was controlled by an electronic circuit that operates a computer-controlled syringe that is connected to a single-channel fluid swivel mounted on a counter-balanced arm above the operant chamber (MED-307A-CT-B2).

Experiment 1: acquisition of corn oil-reinforced and Ensure-reinforced responding

Separate groups of food-restricted male and female WT and CB1 KO mice were trained to nose-poke for either 32% corn oil or 10% vanilla-flavored Ensure under an FR-1 schedule, during daily 30-min acquisition sessions. Ensure is a sweet-tasting food comprised of mixed macronutrients [2.5 g of carbohydrates and 0.4 g of fats per tablespoon is diluted in room temperature tap water. Corn is a pure fat (approximately 14 g per tablespoon) and is brought to a stable emulsion in 3% xanthan gum dissolved in tap water]. We have previously shown that both liquids maintain operant responding in C57BL/6 mice (Ward and Dykstra, 2005; Ward et al., 2007; Ward et al., 2008). In the corn oil study, the number of mice used were as follows: male WT (n=10), male KO (n=12), female WT (n=9), and female KO (n=13). In the Ensure study, the numbers of mice used were as follows: male WT (n=10), male KO (n =7), female WT (n=8), and female KO (n=9). Upon a response on the active, illuminated nose-poke hole, the adjacent cue light was illuminated, and liquid food was available for 20 s. The maximum number of reinforcers available per session was set at 10. Responses on the inactive nose-poke hole and entry into the dipper receptacle were recorded, but were without scheduled consequences. Acquisition of liquid food self-administration was defined as 10 reinforced responses in the active nose-poke hole, with the total responses including at least 75% active nose-poke hole responding. After individual mice reached these acquisition criteria, they proceeded to the FR-1 maintenance phase of the study. Mice that failed to reach the acquisition criteria after 15 days of acquisition testing did not continue on to the FR-1 maintenance phase and received a score of 15 days to meet the criteria for data analysis.

Experiment 2: maintenance of corn oil-reinforced and Ensure-reinforced responding and effect of SR141716

Once individual mice met acquisition criteria, they continued to respond for either 32% corn oil or 10% Ensure under an FR-1 schedule during daily 1-h sessions, for 7 days. Each response on the active, illuminated nose-poke hole resulted in the presentation of liquid food for 8 s, paired with illumination of the stimulus light above the food receptacle and a 1-s tone. The house light and fan remained on throughout the 1 h test session. No maximum number of reinforcers was set. In a subset of mice from the Ensure study (n=4–5/group), SR141716 (0.3–3.0) or vehicle was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) in a randomized manner 15 min before starting FR-1 sessions, in addition to the seven nontreatment sessions, and each treatment session was separated by at least 3 days of nontreatment sessions. An average of 5 days separated the last SR141716 injection and the commencement of the PR experiment.

Experiment 3: progressive ratio responding for corn oil and Ensure

After 7 days of FR-1 responding, all mice continued to respond for either 32% corn oil or 10% Ensure under a PR schedule of reinforcement, during daily 1 h sessions for 5 days, and the following progression of response requirements for reinforcement within each session was used: 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, 145, etc. (as described in Richardson and Roberts, 1996). Breaking point was defined as the number of infusions obtained by the end of the 1-h test session. Responses on the active, illuminated nose-poke hole resulted in the presentation of liquid food for 8 s, paired with illumination of the stimulus light above the food receptacle and a 1-s tone. The house light and fan remained on throughout the session.

Experiment 4: maintenance and progressive ratio responding for cocaine

After completion of experiment 3, chronically indwelling jugular cannulae were surgically implanted (as described by Caine et al., 1999) into mice (n=17) from the Ensure study, and they were then trained to self-administer 0.56 mg/kg/infusion cocaine under an FR-1 schedule of reinforcement, during daily 2-h sessions for 7 days. Each response on the active, illuminated nose-poke hole resulted in the infusion of cocaine paired with illumination of the stimulus light above the food receptacle and a 1-s tone. After FR-1 responding, mice were given access to 0.56 mg/kg/infusion cocaine under the PR schedule of reinforcement described above. Breaking point was defined as the number of infusions obtained by the end of the 4-h test session or until 20 min elapsed with no active-hole nose-pokes.

Drugs

SR141716 (Research Triangle Institute, RTP, North Carolina, USA) was dissolved in a vehicle of 100% ethanol, cremophor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and saline in a ratio of 1: 1: 18 and was injected i.p. at a volume of 0.1 ml/10 g 15 min before behavioral testing. Cocaine hydrochloride (National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, Maryland, USA) was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 1.8 mg/ml for intravenous administration. Pump time was adjusted for each mouse so that the proper infusion was delivered for the administration of 0.56 mg/kg/infusion, with an average pump time of approximately 1 s.

Data analysis

To determine whether genotype and sex (or genotype and SR141716) produced a significant effect on liquid food or cocaine self-administration, and whether they produced a significant interaction, two-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted on the following measures: (i) the number of days to acquire self-administration, (ii) the number of responses/session under an FR-1 schedule on day 7 of maintenance responding, (iii) effect of SR141716 on maintenance responding, (iv) breaking point achieved on day 5 of PR responding, and (v) body weight. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were run to identify specific effects of genotype in males and females, as well as differences in responding between males and females of like genotype. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA).

Results

Effect of CB1 genotype and sex on 32% corn oil self-administration

During the initial acquisition phase, all mice, with the exception of one female WT mouse and two female CB1 KO mice, acquired 32% corn oil self-administration within 15 days (Fig. 1a). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype [F(1,40)=14.43, P<0.01] and sex [F(1,40)=18.41, P<0.01] on the number of days to acquire corn oil self-administration, and a significant interaction [F(1,40)=3.972, P<0.05]. Bonferroni post-test revealed a significant effect of genotype in female mice (P<0.01) but not males, and revealed a non-significant trend of sex in WT mice (P=0.09) and a significant effect of sex in CB1 KO mice (P<0.05).

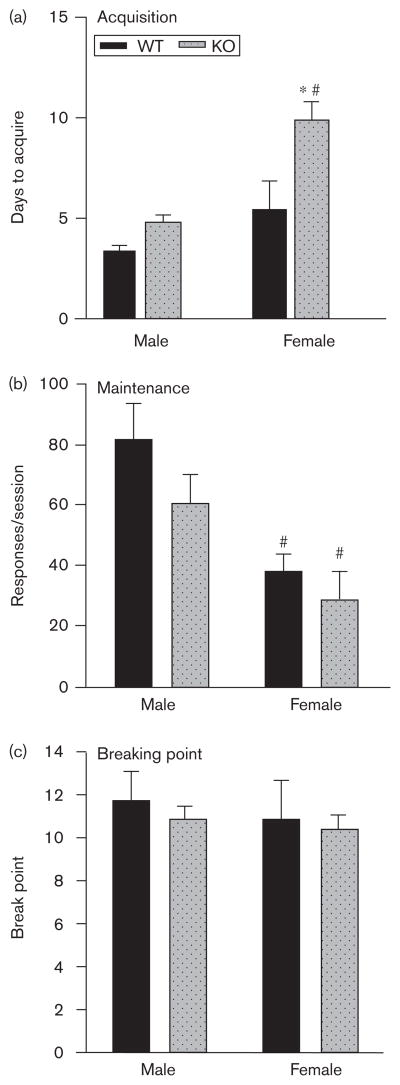

Fig. 1.

Sex×CB1 genotype interactions on acquisition, maintenance, and breaking point in male and female wild type (WT) (dark bars) and CB1 knockout (KO) (light bars) mice trained to self-administer 32% corn oil. (a) Mean (±SEM) number of days to acquire 32% corn oil self-administration. (b) Mean (±SEM) number of 32% corn oil-reinforced nose-pokes per 1 h fixed ratio-1 session. (c) Mean (+ SEM) number of 32% corn oil-reinforced nose-pokes per 2 h progressive ratio session. *Significantly different from WT control (P<0.05). #Significantly different from male mice of like genotype.

Mice that met the acquisition criterion within 15 days were then maintained on 32% corn oil under an FR-1 schedule for 7 days. On the last day of the maintenance phase (Fig. 1b), two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effect of genotype on the number of reinforcers earned, but a significant effect of sex [F(1,37)=12.83, P<0.01], and no significant interaction. Bonferroni post-test revealed no significant effect of genotype in male or female mice, and a significant effect of sex in WT and CB1 KO mice (P<0.05). One male CB1 KO mouse and two female CB1 KO mice died of unknown causes during the maintenance phase, leaving final group sizes of 10 male WT (MWT), 11 male KO (MKO), eight female WT (FWT), and nine female KO (FKO).

The same mice were then trained to self-administer 32% corn oil under the PR schedule. On day 5 of the breaking point phase (Fig. 1c), two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effect of genotype or sex, and no significant interaction on the maximal breaking point was attained. Bonferroni post-test revealed no significant effect of genotype in male or female mice and no significant effect of sex in WT or CB1KO mice. Two male CB1 KO mice died of unknown causes during the breaking point phase.

Overall, genotype produced marginal effects on 32% corn oil responding, with female CB1 KO mice showing a deficit in acquisition as compared with female WT mice. There was a significant effect of sex in CB1KO mice on acquisition of corn oil self-administration, with males acquiring faster than females, and in WT and CB1 KO mice on maintenance, with males responding more under the FR-1 schedule. Final sample sizes were 10 MWT, nine MKO, eight FWT, and nine FKO.

Effect of CB1 genotype and sex on 10% Ensure self-administration

During the initial acquisition phase, all mice, with the exception of two male CB1 KO mice and 1 female CB1 KO mouse, acquired 10% Ensure self-administration within 15 days (Fig. 2a). Two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effect of genotype or sex on the number of days to acquire Ensure self-administration, but a significant interaction of genotype and sex [F(1,30)=6.19, P<0.05]. Bonferroni post-test revealed a significant effect of genotype in male mice (P<0.05) but not females and a nonsignificant trend for sex in either the WT (P=0.058) or CB1 KO mice.

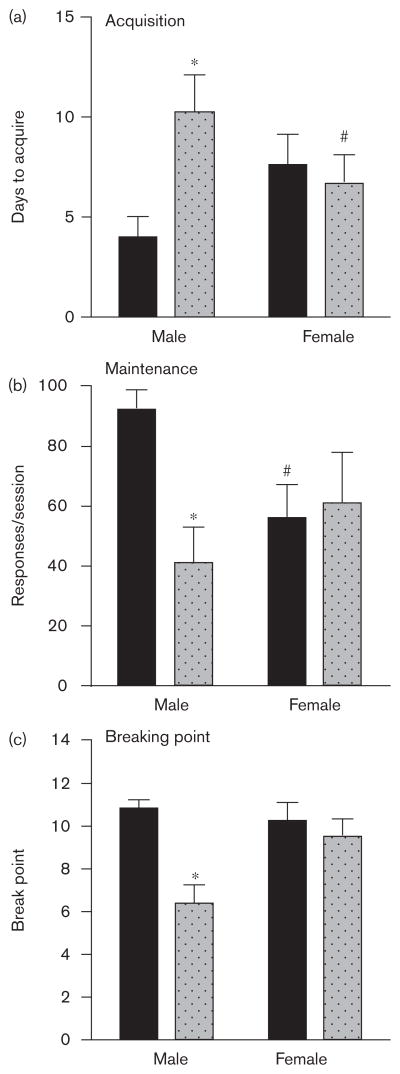

Fig. 2.

Sex×CB1 genotype interactions on acquisition, maintenance, and breaking point in male and female wild type (WT) (dark bars) and CB1 knockout (light bars) mice trained to self-administer 10% Ensure. (a) Mean ( ±SEM) number of days to acquire 10% Ensure self-administration. (b) Mean (±SEM) number of 10% Ensure-reinforced nose-pokes per 1 h fixed ratio-1 session. (c) Mean (+ SEM) number of 10% Ensure-reinforced nose-pokes per 2 h progressive ratio session. *Significantly different from WT control (P<0.05). #Significantly different from male mice of like genotype.

Mice that met the acquisition criterion within 15 days were then maintained on 10% Ensure under an FR-1 schedule for 7 days. On the seventh day of the maintenance phase (Fig. 2b), two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effect of genotype or sex on the number of reinforcers earned, however, a significant interaction was revealed [F(1,27)=4.78, P<0.05]. Bonferroni post-test revealed a significant effect of genotype in male mice (P<0.05) but not females, and a significant effect of sex in WT mice (P<0.05) but not in CB1 KO mice. Two male CB1 KO mice died of unknown causes after the maintenance phase. Final sample sizes were eight MWT, seven MKO, eight FWT, and eight FKO.

The same mice from the maintenance phase were then trained to self-administer 10% Ensure under the PR schedule of Ensure delivery to assess breaking point. On day 5 of the ‘breaking point’ phase (Fig. 2c), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype on the average breaking point achieved [F(1,25)=7.82, P<0.01] but no significant effect ot sex, and a significant interaction [F(1,25)=4.09, P<0.05] of genotype and sex on breaking point. Bonferroni post-test revealed a significant effect of genotype in male mice (P<0.05) but not females, and no significant effect of sex in WT or CB1KO mice. Final sample sizes were eight MWT, five MKO, eight FWT, and eight FKO.

To summarize, genotype and sex produced a significant interaction on 10% Ensure self-administration, with CB1 KO producing overall deficits in responding in male but not female mice. In addition, sex produced partial effects on 10% Ensure responding, with a trend toward faster acquisition in male WT mice versus females, and male WT responding more than female WT mice during the maintenance phase.

Effect of SR141716 on maintenance of Ensure self-administration in male and female WT and CB1 KO mice

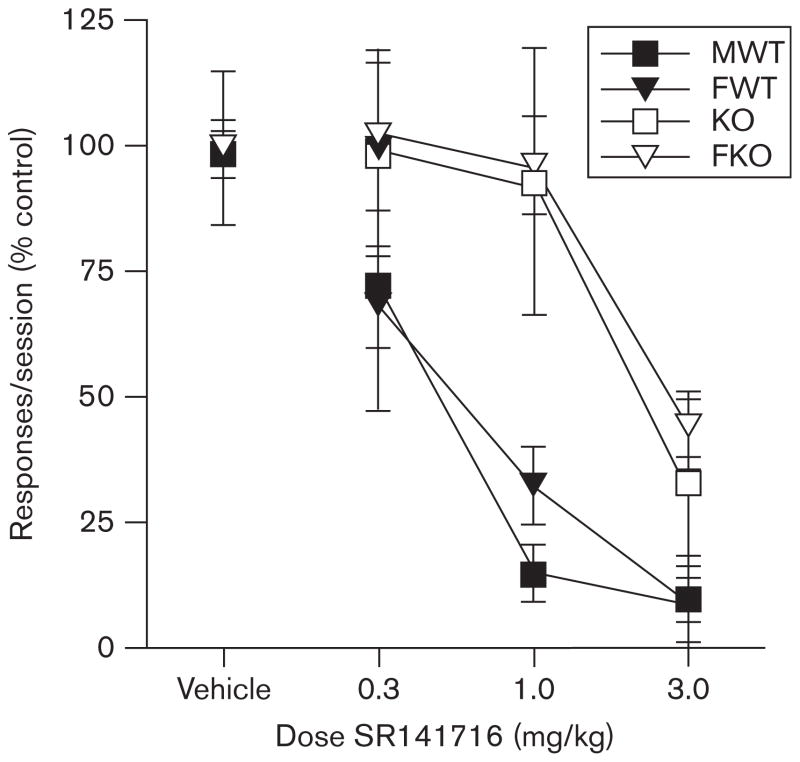

A subset of mice from the Ensure self-administration group were intermittently pretreated with vehicle or SR141716 (0.3–3.0 mg/kg i.p.) on additional test days during their maintenance phase. Pretreatment with SR141716 produced dose-dependent decreases in FR-1 responding for 10% Ensure in all groups (Fig. 3). In WT mice, two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of SR141716 [F(3,20)=23.01, P<0.05] on the number of reinforcers earned, but no significant effect of sex or interaction. In KO mice, two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of SR141716 [F(3,16)=13.03, P<0.05] but no significant effect of sex, and no significant interaction [F(3,12)=10.13, P<0.05]. Calculated SR141716 effective dose of SR that produces a 50% decrease in FR1 responding for each group (ED50s) to produce decreases in responding for MWT=0.48 mg/kg, MKO=2.40 mg/kg, FWT=0.78 mg/kg, and FKO=3.00 mg/kg, showing a five-fold shift in SR141716 potency between male WT and CB1 KO mice, and a four-fold shift between female WT and CB1 KO mice. SR administration did not have a lasting effect in any group, as response levels returned to baseline the day after treatment. For example, on the day before administration with 3.0 SR141716, the average number of active responses in MWT was 107.5 (±16.5), and on the day after administration of this dose, responding averaged 111.3 (±12.5).

Fig. 3.

SR141716 attenuates 10% Ensure self-administration in male (squares) and female (triangles) wild type (solid) and CB1 knockout (open) mice. Data depict mean ( ±SEM) number of 10% Ensure-reinforced nose-pokes per 1 h fixed ratio-1 session after administration of vehicle or SR141716 (0.3–3.0 mg/kg intraperitoneal).

Effect of CB1 genotype and sex on 0.56 mg/kg/infusion cocaine self-administration

After the completion of acquisition, maintenance, and PR responding for 10% Ensure, a subset of mice was cannulated and trained to self-administer 0.56 mg/kg/ infusion cocaine under an FR-1 schedule for 7 days. On the last day of the maintenance phase (Fig. 4a), two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effect of genotype or sex, and no significant interaction on the number of cocaine infusions earned. One male and one female CB1 KO mouse died after the maintenance phase of cocaine self-administration. Final sample sizes were five MWT, four MKO, four FWT, and four FKO.

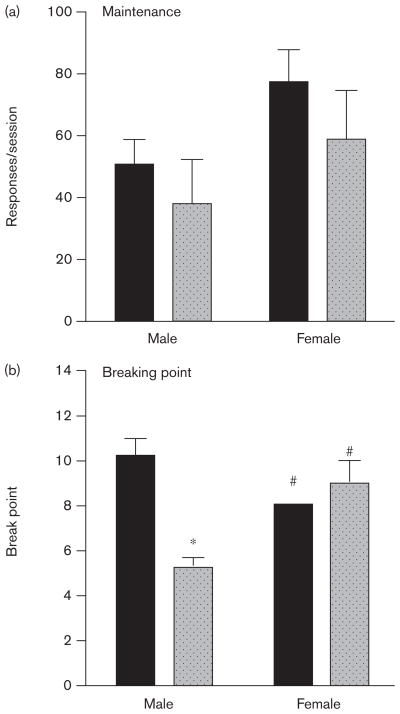

Fig. 4.

Sex× CB1 genotype interactions on maintenance and breaking point in male and female wild type (WT) (dark bars) and CB1 knockout (light bars) mice trained to self-administer 0.56 mg/kg/infusion cocaine. (a) Mean (+SEM) number of cocaine-reinforced nose-pokes per 2 h fixed ratio-1 session. (b) Mean (±SEM) number of cocaine-reinforced nose-pokes per 4 h progressive ratio session. *Significantly different from WT control (P<0.05). #Significantly different from male mice of like genotype.

The same mice were then trained to self-administer 0.56 mg/kg/infusion cocaine under the PR schedule to assess breaking point. On day 5 of the breaking point phase (Fig. 4b), two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype on the mean breaking point achieved [F(1,7)=14.00, P<0.01], but not of sex, and a significant interaction [F(1,7)=31.50, P<0.01]. Bonferroni post-test revealed a significant effect of genotype in male mice, and a significant effect of sex in WT and CB1 KO mice (P<0.05). Two male and one female WT mice lost cannula patency and did not complete the PR study. Final sample sizes were three MWT, three MKO, three FWT, and three FKO.

Overall, genotype and sex produced limited effects on cocaine self-administration, with male CB1 KO mice and female WT mice showing lowered breaking point maintained by cocaine.

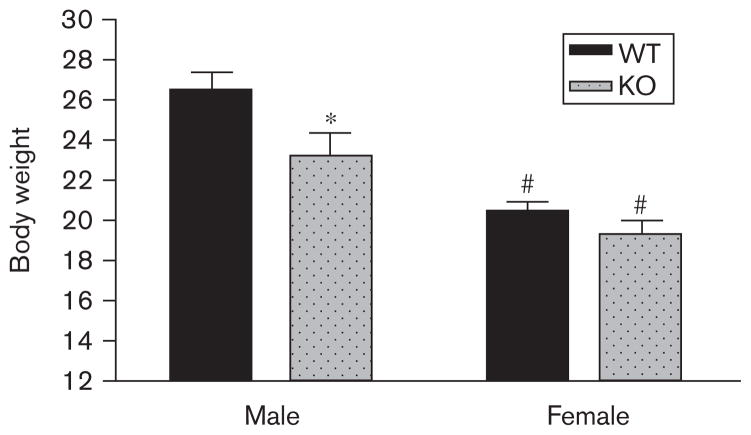

Effect of CB1 genotype and sex on body weight in C57Bl/6 mice

All mice were weighed daily, and two-way ANOVA of body weights mid-way through the maintenance phase revealed significant effects on body weight of genotype [F(1,80)=9.38, P<0.01] and sex [F(1,80)=49.53, P<0.01], but no significant interaction (Fig. 5). Bonferroni post-test revealed a significant effect of genotype in male mice (P<0.01), with WT mice weighing more than CB1 KO mice, but not in females. Bonferroni post-test also revealed a significant effect of sex in WT and CB1KO mice, with male mice weighing more than females.

Fig. 5.

Sex×CB1 genotype interactions on body weight in male and female wild type (WT) (dark bars) and CB1 knockout (KO) (light bars) mice trained to self-administer 32% corn oil. Data depict mean (+SEM) body weights.

Discussion

The present results are, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, the first to show a CB1 genotype× sex interaction on palatable food or cocaine self-administration in operant responding paradigms. Overall, CB1 genotype and sex significantly interacted to produce an attenuation of acquisition and maintenance of Ensure self-administration and PR self-administration of both Ensure and cocaine in male CB1 KO mice. In addition, CB1 KO led to lower body weight in male mice; in comparison, female CB1 KO mice showed no significant deficits on these measures compared with their WT controls. These data are in agreement with a recent report by Diaz et al. (2009) showing a significant interaction between CB1 KO and sex in freely available laboratory chow consumption, wherein CB1 KO produced hypophagia in male but not female mice. Interestingly, this group has also identified differences in cell signaling in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (a site involved in appetite) between male and female guinea pig brain slices, and has shown differential modulation of postsynaptic potentials in this region by the application of CB agonist, suggesting that the sexually dimorphic nature of hypothalamic nuclei may contribute to these sex differences (Diaz et al., 2009). In addition, Gerald et al. (2008) reported significant interactions between genotype and sex on the gene expression of several receptor types within the striatum (a region involved in reinforcement processes), including both μ-opioid and δ-opioid and D1, D2, and D5 dopamine receptors. Lastly, as we have previously reported (Ward and Dykstra, 2005; Ward et al., 2007), male CB1 KO mice showed no deficit in acquisition and maintenance of FR-1 responding or in PR responding maintained by corn oil; however, female CB1 KO mice did show a significant deficit in the acquisition of corn oil self-administration in this study as compared with female WT controls.

Sex differences also arose within genotypes for responding maintained under all three reinforcers. Female WT mice self-administered less Ensure than male WT mice under an FR-1 schedule, and female WT and CB1 KO mice self-administered less corn oil than male WT and CB1 KO mice under an FR-1 schedule, although no sex differences were observed when palatable food self-administration was maintained under the PR schedule. Conversely, no sex differences arose in mice self-administering cocaine under an FR-1 schedule, although a trend toward increased cocaine self-administration in females of both genotypes was seen. This is consistent with a larger literature suggesting that low FR schedules are relatively insensitive to sex differences in the reinforcing effects of psychostimulants, in that although there is a trend toward reports of increased intake under FR schedules, several studies report no significant sex differences (see Roth et al., 2004 for review). Sex differences in psychostimulant self-administration become more apparent under more challenging reinforcement schedules, however, such as PR schedules. For example, female rats reach significantly higher breaking points than males under a PR schedule for several stimulant drugs, including cocaine (Roberts et al., 1989; Carroll et al., 2002; Lynch, 2008). This is in contrast with the present result, wherein female WT mice maintained significantly lower cocaine breaking points under the PR schedule as compared with male WT controls. This may be a species difference, as our result is in agreement with another recent report in C57Bl/6 mice by Griffin et al. (2007), who reported no sex differences in cocaine self-administration under an FR-2 schedule, but a significant attenuation in PR responding for cocaine in female versus male mice. Lastly, as would be expected, female WT and CB1 KO mice also weighed significantly less than their male counterparts.

Pretreatment with the CB1 antagonist SR141716 produced dose-dependent attenuation of Ensure intake under an FR-1 schedule of reinforcement in both male and female WT and CB1 KO mice; however, SR141716 was four to five fold more potent in WT mice than in CB1 KO mice. Haller et al. (2002) report a similar finding, in that 1.0 mg/kg SR141716 produced no effect on anxiety in CB1 KO mice but produced a significant anxiolytic effect in CB1 KO mice at the 3.0 mg/kg dose. Moreover, higher doses of SR141716, but not lower doses, reverse deficient suckling behavior in CB1 KO mice (Fride et al., 2003). These behavioral studies add to a larger literature suggesting that although SR141716 exerts its behavioral effects primarily at the CB1 receptor, effects at higher doses are also likely mediated by other receptor mechanisms, with a novel CB receptor being the most likely candidate (Járai et al., 1999; Zimmer et al., 1999; Di Marzo et al., 2000; Breivogel et al., 2001; see Haller et al., 2002 for review).

The present results with SR141716 failed to show sex differences in CB modulation of palatable food self-administration within each genotype. This is in agreement with Foltin and Haney (2007), who reported no sex differences in the anorectic effect of SR141716 on self-administration of either palatable food or food pellets in male versus female baboons. Conversely, Diaz et al. (2009) showed that the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 produced a significantly more pronounced hypophagia in freely fed male versus female guinea pigs. This discrepancy with the present data may be a result of species differences, an operant versus free feeding model, or the CB1 antagonists used.

In summary, the present data add to a small but growing literature suggesting that the CB system may show differential sensitivity in its modulation of appetitive behavior in males versus females. In addition, these results support previous work from our laboratory showing a relative lack of involvement of the CB1 receptor system in the reinforcing efficacy of palatable fats, and extend these findings to female mice. This set of experiments also reemphasizes the fact that sex is an important and complex determining factor in reinforced behavior, in that sex modulates the various phases of self-administration differently (acquisition, maintenance, breaking point) and in a reinforcer-dependent manner (palatable fat, palatable sweet, cocaine). Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of characterizing the role of specific receptor systems in appetitive behavior across sexes, reinforcer types and reinforcement schedules, and species. Lastly, we report behavioral effects of the highest dose of the CB1 antagonist SR141716 tested in CB1 KO mice, supporting the wider hypothesis that some of the effects of SR141716 can be mediated by other receptors, possibly a yet-undesignated CB receptor subtype. Further work is necessary to characterize in more detail whether and how the CB system differs in males versus females in its involvement in appetite and reward, and to consider the role of sex in future applications of CB drugs in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants F32-DA01931 (S.J.W.), R01-DA014673 (E.A.W.), and P30 DA13429 (M.W.A.). The authors thank Rebecca Hamby for her extensive technical assistance.

References

- Abel EL. Cannabis: effects on hunger and thirst. Behav Biol. 1975;15:255–281. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(75)91684-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthenelli RM, Despres JP. Effects of Rimonabant in the reduction of major cardiovascular risk factors. New Orleans, LA. American College of Cardiology 53rd Annual Scientific Session; 2004. pp. 7–10. Results from the STRATUS-US trial (smoking cessation in smokers motivated to quit) [Google Scholar]

- Arnone M, Maruani J, Chaperon F, Thiebot MH, Poncelet M, Soubrie P, Le Fur G. Selective inhibition of sucrose and ethanol intake by SR 141716, an antagonist of central cannabinoid (CB1) receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132:104–106. doi: 10.1007/s002130050326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Griffin G, Di Marzo V, Martin BR. Evidence for a new G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptor in mouse brain. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK. Method for training operant responding and evaluating cocaine self-administration behavior in mutant mice. Psychopharmacology. 1999;147:22–24. doi: 10.1007/s002130051134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Morgan AD, Lynch WJ, Campbell UC, Dess NK. Intravenous cocaine and heroin self-administration in rats selectively bred for differential saccharin intake: phenotype and sex differences. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;161:304–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossu G, Ledent C, Fattore L, Imperato A, Bohme GA, Parmentier M, Fratta W. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice fail to self-administer morphine but not other drugs of abuse. Behav Brain Res. 2001;118:61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM. Sex differences in behavioral effects of cannabinoids. Life Sci. 2005;77:2471–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Breivogel CS, Tao Q, Bridgen DT, Razdan RK, Zimmer AM, Zimmer A, Martin BR. Levels, metabolism, and pharmacological activity of anandamide in CB (1) cannabinoid receptor knockout mice: evidence for non-CB (1), non-CB (2) receptor-mediated actions of anandamide in mouse brain. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2434–2444. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz S, Farhang B, Hoien J, Stahlman M, Adatia N, Cox JM, Wagner EJ. Sex differences in the cannabinoid modulation of appetite, body temperature and neurotransmission at POMC synapses. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;89:424–440. doi: 10.1159/000191646. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E, Foox A, Rosenberg E, Faigenboim M, Cohen V, Barda L, et al. Milk intake and survival in newborn cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice: evidence for a ‘CB3’ receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;461:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Haney M. Effects of the cannabinoid antagonist SR141716 (rimonabant) and d-amphetamine on palatable food and food pellet intake in non-human primates. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:766–773. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW, Byrne MF. Effects of smoked marijuana on food intake and body weight of humans living in a residential laboratory. Appetite. 1988;11:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(88)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerald TM, Howlett AC, Ward GR, Ho C, Franklin SO. Gene expression of opioid and dopamine systems in mouse striatum: effects of CB1 receptors, age and sex. Psychopharmacology. 2008;198:497–508. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1141-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC, III, Randall PK, Middaugh LD. Intravenous cocaine self-administration: individual differences in male and female C57BL/6J mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Bakos N, Szirmay M, Ledent C, Freund TF. The effects of genetic and pharmacological blockade of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor on anxiety. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1395–1398. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S, Williams CM, Kirkham TC. Cannabinoid influences on palatability: microstructural analysis of sucrose drinking after delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol, anandamide, 2-arachidonoyl glycerol and SR141716. Psychopharmacology. 2003;165:370–377. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Járai Z, Wagner JA, Varga K, Lake KD, Compton DR, Martin BR, et al. Cannabinoid-induced mesenteric vasodilation through an endothelial site distinct from CB1 or CB2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14136–14141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists as promising new medications for drug dependence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:875–883. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.077974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ. Acquisition and maintenance of cocaine self-administration in adolescent rats: effects of sex and gonadal hormones. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:237–246. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin PJ, Winston K, Swezey L, Wisniecki A, Aberman J, Tardif DJ, et al. The cannabinoid CB1 antagonists SR 141716A and AM 251 suppress food intake and food-reinforced behavior in a variety of tasks in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2003;14:583–588. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CC, Murray TF, Freeman KG, Edwards GL. Cannabinoid agonist, CP 55 940, facilitates intake of palatable foods when injected into the hindbrain. Physiol Behav. 2004;80:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council of the National Academies. Guidelines for the care and use of mammals in neuroscience and behavioral research. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolaro D, Viganò D, Rubino T. Endocannabinoids and drug dependence. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:643–655. doi: 10.2174/156800705774933014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penetar DM, Kouri EM, Gross MM, McCarthy EM, Rhee CK, Peters EN, Lukas SE. Transdermal nicotine alters some of marihuana’s effects in male and female volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer FX, Aronne LJ, Heshmati HM, Devin J, Rosenstock J RIO-North America Study Group. Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients: RIO-North America: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:761–775. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncelet M, Maruani J, Calassi R, Soubrie P. Overeating, alcohol and sucrose consumption decrease in CB1 receptor deleted mice. Neurosci Lett. 2003;343:216–218. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Bennett SA, Vickers GJ. The estrous cycle affects cocaine self-administration on a progressive ratio schedule in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;98:408–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00451696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth ME, Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the vulnerability to drug abuse: a review of preclinical studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis-Segura C, Cline BH, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Spanagel R. Reduced sensitivity to reward in CB1 knockout mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:223–232. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M, Panlilio LV, Antoniou K, Pappas LA, Goldberg SR. The cannabinoid CB1 antagonist N-piperidinyl-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl) -4-methylpyrazole-3-carboxamide (SR-141716A) differentially alters the reinforcing effects of heroin under continuous reinforcement, fixed ratio, and progressive ratio schedules of drug self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:93–102. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria G, Mendizabal V, Tourino C, Robledo P, Ledent C, Parmentier M, et al. Lack of CB1 Cannabinoid Receptor Impairs Cocaine Self-Administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1670–1680. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton-Jones ZD, Vickers SP, Clifton PG. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A reduces appetitive and consummatory responses for food. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:452–460. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor K. Panel advises against rimonabant approval. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1460–1461. doi: 10.2146/news070065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaal LF, Rissanen AM, Scheen AJ, Ziegler O, Rossner S RIO-Europe Study Group. Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet. 2005;365:1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuri VK, Janero DR, Makriyannis A. Pharmacotherapeutic targeting of the endocannabinoid signaling system: drugs for obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:671–686. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ, Dykstra LA. The role of CB1 receptors in sweet versus fat reinforcement: effect of CB1 receptor deletion, CB1 receptor antagonism (SR141716A) and CB1 receptor agonism (CP-55940) Behav Pharmacol. 2005;16:381–388. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200509000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ, Walker EA, Dykstra LA. Effect of cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A and CB1 receptor knockout on cue-induced reinstatement of Ensure and corn-oil seeking in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2592–2600. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ, Lefever TW, Jackson C, Tallarida RJ, Walker EA. Effects of a Cannabinoid1 receptor antagonist and Serotonin2C receptor agonist alone and in combination on motivation for palatable food: a dose-addition analysis study in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:567–576. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer A. Manipulating the genome by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992;15:115–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.000555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer A, Zimmer AM, Hohmann AG, Herkenham M, Bonner TI. Increased mortality, hypoactivity, and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5780–5785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]