Abstract

We sought to identify what abused Peruvian women want or need as intervention strategies. We conducted five focus groups with thirty women with prior or current experience with intimate partner violence. Participants noted that abused women need compassionate support, professional counseling, informational and practical (e.g., work skills training, employment, shelter, financial support) interventions. We propose a two-tiered intervention strategy that includes community support groups and individual professional counseling. This strategy is intended to offer broad coverage, meeting the needs of large groups of women who experience abuse, while providing specialized counseling for those requiring intensive support. Respect for each woman’s autonomy in the decision-making process is a priority. Interventions targeted towards women and men should address structural factors that contribute to violence against women.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, Peruvian women, intervention, social cultural barriers

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is a global public health problem and is one of the public health concerns in Perú. IPV includes physical or sexual violence, threats of physical or sexual violence, and emotional abuse. The term “intimate partner” includes former and current spouses or partners. Recent evidence suggests that Peruvian women experience a great deal of IPV with a lifetime prevalence of 45.1% for any physical, sexual and emotional abuse (Perales et al., 2009).

Structural violence refers to ways in which social structures harm or otherwise disadvantage individuals. It impacts the everyday lives of people yet remains invisible and normalized. Situating violence against women as interconnected with structural violence allows us to understand the different types of violence impacting the lives of Peruvian women. Anthropological studies on violence highlight the intimate connection between structural violence and interpersonal violence and reveal that the family can become a violent institution as a result of larger socio-economic conditions which make violence available (Alcade, 2010; Scheper-Hughes, 1992). The description of structural violence is provided as contextual information to help with the understanding of violence against women in Perú. As such, structural violence was not empirically assessed in this study.

Violence against women in Perú has deep social, cultural, economic, and political roots (Alcade, 2010; Rondon, 2003), also known as structural factors. Girls are raised according to traditional religious culture with Virgin Mary as their role model (marianismo). In this culture, women are taught to be passive, submissive and dependent on their spouses or partners. Motherhood and being a homemaker is valued highly (Rondon, 2003). Women who do not conform to these stereotypes are denigrated. Perú is also characterized as a patriarchal society where men have dominance (machismo; Flake, 2005). In a patriarchal society, women are likely to be abused when they challenge the patriarchal power structure. As a result, women tend to submit to their spouses or partners to reduce the likelihood of abuse (Flake, 2005; Instituto Nacional de Estadiatica e Informatica, 2006).

Our understanding of gender violence in Perú goes beyond an explanation of patriarchy as expressed by machismo and marianismo. The ecological framework proposed by Heise (1998, 2011) acknowledges that male dominance is a foundation for any comprehensive theory of violence. This framework focuses on the multifactorial nature of the etiology of violence rather than single factor (Heise, 1998, 2011). In the Americas, violence against women is intimately bound to continuing legacies of colonialism, racism, and subordination (Smith, 2005). This is particularly true in the case of Perú, where violence against women is also enabled and maintained by the state (Boesten, 2012), occurs on multiple levels, and is informed at every level by ideologies of race, class, and gender (Boesten & Fisher, 2012; Rondon, 2003). This can most clearly be seen by the cases of forced sterilization of primarily Quechua and Aymara women from 1996 to 2000, and in the systematic use of sexual violence against indigenous women during the armed conflict between the Communist Party of Perú, Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) and the Peruvian state (Boesten & Fisher, 2012; Rondon, 2003). The use of sexual and gendered violence by armed groups reflects the “magnification of existing institutionalized and normative violence against women” (Boesten, 2012; p. 367).

Perú, characterized as a “middle income” country, is plagued with vast disparity in living conditions and welfare. There have been strides to reduce poverty. An estimated 11.5% of Peruvians were living in extreme poverty in 2009, compared to 23% in 2002 (United Nations Development Programme, 2010). However, infrastructure, gender and ethnic inequalities still persist in Perú, despite reduction in poverty (The World Bank, 2012; United Nations Development Programme, 2010). Reduction of poverty in Perú is not related to reduction of inequalities. Discrimination against women and indigenous populations is a strong component of economic inequality (Lustig, Lopez-Calva, & Ortiz-Juárez, 2012). In summary, many factors contribute to Peruvian women’s experience of and vulnerability to IPV, including social cultural norms of viewing violence as “normal” in a woman’s life, patriarchy, dependence on spouse or partner for financial and emotional support, state-enabled violence, and discrimination against women and indigenous populations.

In Latin America, legal and policy reform in the area of violence against women do little to alleviate its persistence. Although Perú was one of the first Latin American countries to develop legislation and policy to address violence against women in the 1990s, policy and legislation designed to curb violence against women in Perú are poorly enforced and under-resourced (Boesten, 2012). Policies lack a clear legal framework, fail to address the underlying causes of IPV, and in some cases, contribute to reproducing (at the institutional level) the sexist, racist, and classist hierarchies that permeate Peruvian society. Women remain at high risk for IPV despite the adoption of special legislation on domestic violence and establishment of women’s police stations and one-stop centers that offer legal, psychological and social assistance to victims of violence. The Ombudsman Office of Perú, created to combat human rights violations, discrimination and incompetent administration, has also determined that the health sector lags in identifying IPV among those who access the healthcare system (Defensoría del Pueblo del Perú, 2010). Intervention for women who experience abuse continues to be a critical need. Despite the importance of understanding what women want and need as intervention for IPV, few studies have specifically sought to ascertain these needs (Belknap & Vandevusse, 2010; J.G. Burke, Denison, Gielen, McDonnell, & O’Campo, 2004; J. G. Burke, Gielen, McDonnell, O’Campo, & Maman, 2001; Chang et al., 2005; Dienemann, Campbell, Wiederhorn, Laughon, & Jordan, 2003; Gonzalez-Guarda, Cummings, Becerra, Fernandez, & Mesa, 2013). However, theses studies have focused on the needs of Caucasian and Hispanic women who experience IPV in the United States. To our knowledge, there has only been one reported pilot intervention study on women who experience IPV in Perú (Cripe et al., 2010). This study utilized the empowerment model (Dutton, 1992; McFarlane & Parker, 1994). As a result, we reasoned that greater understanding of the needs of Peruvian women exposed to IPV is critically important as an initial step towards preventing and mitigating the adverse effects of IPV. We conducted a study to identify the types of intervention strategies most likely to fit the needs and preferences of abused women in Lima, Perú. We expect that findings from this study will help to inform the design of intervention programs relevant to reducing the prevalence and impact of IPV among women in Lima, Perú.

METHODS

The qualitative research approach provides a deeper understanding of participants’ perspectives than traditional quantitative methods (Sofaer, 1999). The all-female field research team (four members including a project manager, a social worker, an anthropology doctoral student, and a psychology student) received training on participant recruitment and focus group facilitation prior to initiation of focus group meetings. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Hospital Dos de Mayo, Hospital Edguardo Rebagliati Martins, and the University of Washington, and the battered women’s shelter administrators.

Recruitment

We used a purposive sampling technique to recruit women with prior or current experience with IPV to participate in focus groups. We recruited women from family planning and gynecologic clinics of Hospital Dos de Mayo and Hospital Edguardo Rebagliati Martins, Lima, Perú, and from a battered women’s shelter, two weeks before the focus groups were conducted. A nurse at the clinic in each of the hospitals and a staff member of the women’s shelter approached women to determine their interest in learning more about the study. Interested women were then introduced to one of the research team members. Women between the ages of 19 and 44 years of age at family planning or gynecologic clinics and the women’s shelter, who spoke Spanish, without any mental disability, and who answered affirmatively to any of the two screening questions were invited to participate in the focus groups.

All recruitment procedures were conducted in private settings. The research team member screened potential participants using questions adapted from the Abuse Assessment Screening (AAS) questionnaire (McFarlane & Parker, 1994). Women were asked, “During the last 12 months, have you been pushed, shoved, slapped, hit, kicked or otherwise physically hurt by a current or former spouse or boyfriend?” and “During the last 12 months, have you been forced into sexual activities by a current or former spouse or boyfriend?”

Focus group protocol

The Institutional Review Boards of Hospital Dos de Mayo, Hospital Edguardo Rebagliati Martins and the University of Washington, and the battered women’s shelter administrators approved the study protocol. We conducted five focus groups of three to eight participants during the months of April and May, 2009. Focus groups of three to eight participants are generally referred to as mini-focus; and are regarded as being consistent with facilitating more personal and detailed sharing (Krueger & Casey, 2000), critical for a very sensitive topic of discussion. We scheduled focus groups at various times and days during the week at two hospitals and at the battered women’s shelter to offer participants maximum flexibility for their schedules.

Three research team members, experienced in qualitative data collection, shared responsibility for facilitating and recording notes during each focus group discussion. All focus group discussions were conducted in Spanish. Two of the focus group facilitators were of Peruvian descent, while another was of indigenous Mexican descent. We audio-recorded all focus group discussions. Subject participation lasted approximately 2.5 hours. Before the start of the focus group discussion, the facilitator read aloud the consent form, and all participants provided individual written consent. Participants also completed a structured questionnaire to collect demographic information (e.g., age (≤ 24, 25–29, 30–34, ≥ 35), marital status (married, living with partner; single, living with partner; separated), education level (>11, 7–11, ≤ 6), occupation (employed, not employed), and length of abuse (<3 years, ≥ 3 years).

We conducted all focus groups using general principles of group facilitation such as active listening, being flexible when necessary, accepting all ideas and opinions as valid, being non-judgmental, and being sensitive to individuals who do not want to reveal information (Krueger & Casey, 2000). We used an open topic schedule to guide the focus groups, leaving freedom to explore issues that emerged in the discussion. We recognize that women recruited for the focus groups are from and know of other women at different stages of response towards their experiences of IPV. We used the following questions to guide focus group discussions: Can you describe the types of intervention strategies that would be most appropriate for women who (a) do not recognize that abuse is not acceptable; (b) recognize the negative impact of abuse, but are committed to stay and not ready to leave; (c) seriously consider how to end violence; (d) leave with intent to end relationship and/or are uncertain about relationship?

A research team member was available to consult with any participant during the focus groups in the event that a participant experienced emotional trauma from being in a focus group or disclosed life-threatening circumstances. If a focus group facilitator felt that a participant was in danger from her abuser or of harming herself, she asked the participant to meet with this research team member after the focus group to discuss follow-up counseling and referral.

Data Analysis

We used qualitative data analysis methods described by Krueger and Casey (2000). Audio tapes of the focus groups were transcribed verbatim in Spanish by two native Spanish speakers. Translation of Spanish transcripts to English was done verbatim and in consultation with Peruvian researchers to ensure accuracy and cultural relevance. Four members of the research team (two of these individuals are Peruvian) reviewed the focus group transcripts and independently coded the transcripts using thematic codes consistent with the study aim (i.e., what women need and want in terms of intervention for IPV). They then compared their coding and discussed any differences in interpretation. The list of codes was iterative, and a final coding scheme was developed from the list and applied to all five transcripts (e.g., who women sought help from, friends, family, police). Text was examined for recurring themes, e.g., seeking psychological counsel. Finally, research team members reviewed, discussed and summarized key themes that emerged from the focus groups to ensure consistency and guard against bias (Krueger & Casey, 2000).

RESULTS

A total of 30 women participated in five focus groups, of which 13 were from the battered women shelter. Demographic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1. Approximately one-third of participants were under 30 years of age and over one-third were 35 years and older. The majority (87%) of participants had less than 11 or 11 years of formal education and 60% of the women were employed. Approximately 76% of participants were unmarried and 70% had fewer than three children. Slightly more than 50% of participants were currently living with an abusive partner, have lived with an abusive partner for less than 7 years and experienced IPV for less than three years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants, N = 30

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤ 24 | 6 | 20.0 |

| 25 – 29 | 4 | 13.3 |

| 30 – 34 | 8 | 26.7 |

| ≥ 35 | 12 | 40.0 |

| Years of formal education | ||

| > 11 | 4 | 13.3 |

| 7 – 11 | 22 | 73.3 |

| ≤ 6 | 4 | 13.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married, living with partner | 7 | 23.3 |

| Single, living with partner | 13 | 43.3 |

| Separated | 10 | 33.3 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 18 | 60.0 |

| Not employed | 12 | 40.0 |

| Number of living children | ||

| 1 | 12 | 40.0 |

| 2 | 9 | 30.0 |

| ≥3 | 9 | 30.0 |

| Currently living with abusive partner | ||

| Yes | 17 | 56.7 |

| No | 13 | 43.3 |

| Length of relationship with abuse partner (years) | ||

| < 7 | 16 | 53.3 |

| ≥ 7 | 14 | 46.7 |

| Length of abuse (years) | ||

| < 3 | 17 | 56.7 |

| ≥ 3 | 12 | 40.0 |

We summarized intervention strategies that women in our focus groups thought that other women with similar experiences of IPV in Lima would want and need. Focus group participants and abused women will be referred to as participants and women, respectively, hereafter.

What women need and want?

Help to recognize that abuse is unacceptable

Participants shared that many women do not recognize that abuse is a problem or do not want to accept that it is an issue in their relationship. They underscored the importance of helping women recognize that abuse is a problem, is not acceptable, and it has adverse effects on woman and her children. One participant said that she knew several women who are abused who just do not want to recognize it.

Compassionate support and encouragement to seek help

Participants endorsed the fact that women need continued compassionate support and encouragement to take action, seek help, and consider a non-violent life. The encouragement has to be continuous and frequent, as the route to non-violence is fraught with difficulties, which the women themselves brought to the discussion. The difficulties include financial and emotional dependence, the temptation to return to the relationship after leaving because they think the husband or partner has changed, pressure from the children, or because they miss the partner, and emotional aftermath of exposure to violence, i.e., they re-experience the trauma.

Some participants noted that it is important to talk to a woman when she is experiencing abuse and preferably, on a regular basis to help women grow in independence and have greater self-confidence. Participants said:

“Also, her self-esteem shouldn’t be that low. She needs to be brave. Strong so that she can move forward.”

“It’s not easy, it’s hard to have this instability but you have to love and value yourself as a woman. If you don’t then nobody else will respect you. You have to seek help, ask for support…little by little you will heal.”

Two women emphasized that abused women need encouragement to be strong, be brave and take action, and say “no more” to abuse and to leave the relationship. The participants noted that women who have successfully left abusive relationships would benefit from having emotional support and life coaching, affirming their decision to leave. Some expressed,

“By going to her home and supporting her, telling her that she has made a good decision by leaving and that maybe one day he will realize what he has done.”

“To not dwell on the past because the past is behind you and if she’s brave she has to move forward with her children. The step that she took was a good step. She has to keep looking forward, toward the future.”

A few participants stated that women may feel that it is not possible to be financially and emotionally independent. Continued encouragement and support is needed to instill confidence in women and that they can work with their own hands:

“There’s a job for everybody.”

“We have to learn how to speak for ourselves. We have to work! We have to work! Thank God I am healthy, I have hands, eyes, I’m not handicapped, I can work wherever and with that money I can support my children. I was abused but that was only because I depended on him. Now I am grateful, I work and I am strong.”

The participants mentioned that if women are considering leaving their abusive relationships, they should be encouraged to make a decision, to be firm on that decision, and continue to move forward. They need to be aware of temptations to return to their abusive partners. They noted that if a woman decides to leave the abusive relationship, it is better for her to not return to the relationship as the violence is likely to escalate and the situation can be worse than before she left the relationship. Some participants commented,

“In this situation, the woman has decided to go, no? But she’s doubtful, she’s thinking, ‘poor spouse’. But we, as people who have lived through that already, have to help her understand better. Sometimes they say, ‘Poor spouse, I love him. He’s going to change. He’s promised to change if I give him another chance.’ But the situation becomes worse. It was worse for me, I went back and it was worse. The abuse become worse, they don’t let you go anywhere. The abuse then becomes sexual. It’s worse. You left, you came back, it’s worse. You should never go back.”

Participants indicated that women continue to experience the trauma of abuse after they have left the abusive relationship. Women need compassionate support when they re-experience the trauma of abuse in their minds. A woman said:

“If suddenly memories of what she has lived in the past come back to her, she has to say, no, that’s in the past, that already happened. Because sometimes memories come back to you. Or when you meet somebody new, the fear of the abusive relationship comes back.”

Separation from an abusive spouse or partner may not be complete, especially when there are children involved. There were also concerns about retaliation from the abusive spouse or partner. As a result participants mentioned that women should take action to protect themselves and their children. If the abusive partner or spouse continues to be aggressive, then the women need to take further steps to move away and to ensure that their new location is not known to the abuser. Some participants said:

“It’s between you and your partner but sometimes you separate and if you have children you’re never going to really separate from him because he’ll always be there for the son. He’s going to be at birthdays, at family events. You’re always going to be seeing him. You’re never going to really separate.”

Professional psychological support

Participants indicated that women want professional psychological support as a means to manage or mitigate the adverse impacts of IPV. Professional psychological support is offered at some battered women shelters and Ministerio de la Mujer y Desarrollo Social (MIMDES; Ministry of Women and Social Development, also known as Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations). However, not all women who need or want professional psychological therapy have access to it because there is a lack of prioritization of funds for mental health care in state-run services and private insurance does not cover mental health. They said:

“Yes, psychological support but it costs money to go to a psychologist and many times we don’t have the financial resources to go to them.”

Participants expressed that children in abusive families need therapy also.

Practical support

Participants emphasized that women need tangible support, both in finding employment and shelter, and in legal and police protection for themselves and their children. Some participants said:

“Giving her shelter.” “Tell her that we also were once in her situation and that we came to the shelter and they have helped us here, they give us food to eat and a roof over our heads. Tell her that the violence can escalate and that you really can’t judge the risk of being with a violent, aggressive partner.”

“She needs to go to legal services so that she can have a protection order and be sure nothing will happen to her.”

Help in understanding abusive partners

Participants recognized that while women need to seek help, it would also be helpful if they understood their partners, their abusive tendencies and that help existed for perpetrators to break the cycle of violence. The participants recognized that their abusive partners or spouses need help also. Notably, participants reasoned that the abusive nature in their partners or spouses may be attributable to their own upbringing. A participant said:

“It’s difficult because this isn’t recent, it’s not because you were married. It comes from childhood. If you were born into and raised in a violent household, then you marry and your household is also violent. This has been my situation. Sometimes your spouse isn’t bad, he isn’t bad, but sometimes he’s lived in a household where there was abuse. Sometimes I’m like that too, I push him. These talks should be for both partners, for the couple because my spouse comes from a very violent family, his father was a drug addict and his mother would allow him to hit her. What can come of that if not more violence and more abuse?”

However, there is awareness of the difficulty in getting men to accept that something may be wrong with them and that counseling might be useful. A participant said:

“Men also. Men also have to be a part of this, no? Of meeting with a psychologist (small laughter). But they don’t accept. Men are ‘machistas’, he says ‘that’s for crazy people, I’m not crazy, you’re the one who is crazy’ (laughter).”

Who can offer help to women?

Participants noted that social support and counsel from peers (other women who have had similar experiences of abuse), friends, family members, and professionals are critical. They said:

“My family helped me, my mother, my sisters. Everybody. They supported me, they advised me, they would talk to me. I had a son and my partner wasn’t his father and he lived with us and my partner would often hit me in front of him. I realized it after two years, thanks to my family and their advice. My mother would even cry, she would say please leave him, he’s not a good man for you. She would say I would be better off alone with my son.”

Women indicated that their family members had mixed responses when they learned about the abuse. Some family members may encourage women to leave the abusive relationship while others may encourage women to endure, or simply may not wish to be involved. A participant said:

“Well, sometimes fathers, because mothers don’t do this, but if we tell them that we don’t want to be in the relationship anymore they tell us that we have to stay for the sake of the children. You are doing harm, they tell us. So, I tell another family member and they tell me, yes, we’re going to help you, leave, report the abuse. There’s always the good and the bad in a family.”

Participants emphasized that friends play an important role and are a good source of emotional support for women if family members are not supportive. They also endorsed the notion that peers -- other women who have had experiences with IPV are likely to have a greater influence and be more effective advisors to women. They remarked that peers are more likely to be listeners and coaches given their own past experiences with violence, and efforts to seek help.

Alongside family members, friends and peers, professionals including psychologists who work at the schools, MIMDES and Defensoría Municipal del Niño, Niña y Adolescente (DEMUNA, Municipal Ombudsman for Children and Adolescents), and social workers can offer counsel not only to the woman, but also to the couple.

Why do women remain with the abusive partners?

Participants offered several strong opinions and suggestions about why women remain in abusive relationships. Below we summarize several themes that emerged from the focus groups. They felt that some women could not leave the abusive relationships because of their fear of being accused of abandoning their relationships by family and friends. For some women, fear of being alone and living independent of spouse or partner exists. Participants expressed:

“Not all women think the same, some women don’t want to lose their spouse, they don’t want to be alone. They’re afraid to confront life on their own with children, or they’re still dependent on their spouse. They fear this and it doesn’t matter how bad the abuse is, they’re still there.”

Financial dependence was endorsed as a tremendous obstacle for women to overcome when attempting to take steps towards leaving an abusive relationship. Participants endorsed the notion that women fear the unknown of not having shelter, employment or the means to support themselves and their children. In addition, the level of support offered by a woman’s family influences a woman’s decision to leave the abusive relationship. A participant said that women may not seek help because of diminished self-worth and lack of information about legal resources available to help them protect themselves and children from abusive partners.

Participants noted that women may remain with the abusive partner because of their love for the abusive partner and their children. Sometimes, women may not want to seek help from psychologists because they are not ready to leave the relationship and fear that the psychologist may advise them to separate. Importantly, participants noted that children are often used by abusive partners as leverage against their victims. Participants remarked that women remain with violent partners in part because they fear losing their children, and because children left behind in violent households will themselves become victims of abuse:

“The spouse tells her, I am going to take the kids away from you, I am going to do something to you. Because when there is a separation, that’s the first thing he [abusive partner] says. That’s what happens. That’s why, sometimes, this prevents women from moving forward.”

DISCUSSION

The overarching theme to participants’ discussions was an emphasis of abused women’s needs to have ongoing compassionate support, professional psychological therapy and practical interventions including work skills training, employment opportunities, housing, and financial support. These needs and wants are critical to counter the barriers that hinder women from making a decision to take action to protect themselves and their children from violence. Peers, friends, family members, psychologists and social workers were regarded as important sources of support for women whether they decide to remain in or leave their abusive relationships.

Our findings that women need job skills training and employment opportunities are consistent with results of a prior study in North Carolina (Petersen, Moracco, Goldstein, & Clark, 2003) and Hispanics in the United States (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2013) where women expressed a great need for referral to job skills’ training, and assistance in finding work and housing. Overall, results from our study are consistent with findings from a number of studies that have been conducted in the US (Chang et al., 2005; Gerbert, Abercrombie, Caspers, Love, & Bronstone, 1999; Gerbert et al., 2000; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2013; Petersen et al., 2003). The suggestions for IPV interventions offered by participants in our study differed from findings reported by Gerbert et al. (1999, 2000) and Chang et al. (2005) in that the interventions were not specific to health care settings.

Study participants noted that some Peruvian women who experience IPV are not aware that IPV is unacceptable. Peruvian women, in general, are raised to be submissive and good wives who are dependent on their spouses or partners (Rondon, 2003). As a result, women more readily accept abuse as part of an intimate relationship. This mindset is reinforced when women face violence that is enabled and maintained by the state (Boesten, 2012). Recent studies show that rather than protecting battered Peruvian women, in some cases, interventions actually further victimize women who seek services for intimate-partner violence (Alcade, 2010; Boesten, 2012). For example, service providers such as forensic doctors, police officers, among others serve as “gatekeepers” – having the power to influence how the case will play out. Important to note is that decisions made by service providers are often made arbitrarily, as is the case of a forensic doctor having to determine if a woman’s physical injuries are sufficient to determine that the woman is the victim of an assault instead of a misdemeanor. The arbitrariness of the decision also includes service providers’ understanding of violence as purely physical (Boesten, 2012). Inadequate training for service providers also manifest in them victimizing women seeking help by imbuing their case-management with racist, sexist, and classist ideologies (Alcade, 2010). Participants in this study also spoke to this:

“They [police officers] don’t listen to us. They say they do but they don’t. Sometimes we’re right there in front of them with our faces and bodies swollen from the beatings, with our tears, and we want to tell them all that we suffer but they don’t care. They say it’s our fault. We feel worse because we can’t share out stories with them.”

Shelters are a common resource battered women attempt to access. Women are referred to shelters by the police, feminist organizations, or other agencies, or as a last resort after having been denied assistance from other agencies. Yet, most shelters have strict guidelines about the duration a woman and her children are allowed to stay in the shelter, activities women are allowed to participate in while at a shelter (going out to work or to find housing are often denied due to safety measures), and actions women are encouraged and often forced to take in regards to conciliation, separation, and parenting plans. In this way, battered women also experience institutional violence and victimization in shelters.

Participants noted the general difficulty for women to make a decision to take action to protect self and children. Part of this ambivalence is rooted in the general low self-esteem and lack of confidence that they can be emotionally and financially independent from their spouses or partners (Alcade, 2010; Rondon, 2003), and the lack of employable skills. Consequently, some women do not view themselves as being able to support themselves and their children. In addition, some women fear that they will lose custody of the children or they do not want the children to grow up without a father if they made a decision to leave the abusive relationship. There is the cultural expectation for preserving the family structure (Klevens et al., 2007), especially when there are children involved as children’s well-being is regarded highly (Acevedo, 2000). However, participants who have left abusive relationships were confident that with compassionate support, encouragement, and practical interventions, such as shelter and employment, abused women would be able to overcome these social, cultural and economic barriers when they decide to move forward and leave the abusive relationship.

While not all abused women decide to leave the abusive relationship, participants speaking from their own experiences were quick to point out that if a woman decides to leave her abusive spouse or partner, then it would be best for her to remain separated and not return to the abusive partner as the spouse or partner may retaliate. Some participants who returned to their former relationships shared that the abuse experienced after they returned was worse than that experienced before they left their relationships. Power dynamics in a couple play an important role in the likelihood of experiencing abuse. In the Perúvian culture, men have dominance and they may resort to violence to reestablish control if they are unable to maintain culturally sanctioned dominance (Flake, 2005).

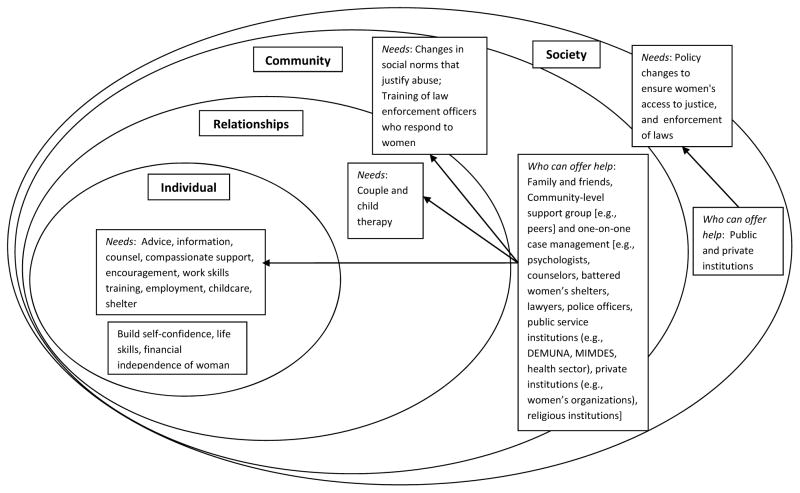

Proposed model of intervention

On the basis of findings from our present study and from our review of the literature, interventions that aim at improving the lives of and reducing violence against women and children should address the social, cultural, political and economic factors that influence IPV. These structural factors interact at multiple levels within a nested hierarchy (see Figure 1 adapted from the ecological framework; Heise, 1998, 2011). We propose a two-tiered intervention strategy to mitigate the impact of IPV in Lima, Perú. This strategy focuses on intervening at the individual and relationship levels of the ecological framework, and complements the work of public and private institutions focused on changing social norms and national level policies that justify abuse and promote gender inequity at the community and society level. The proposed two-tiered intervention approach offers both broad coverage (e.g., community support groups) and in-depth individual counseling (e.g., by professionals) to support women as they try to overcome the social, cultural, economic and political barriers that hinder them from seeking help (see Figure 1). Community support groups can effectively address expressed needs concerning the provision of safe environments where women can come together to initiate and maintain mutually supportive relationships while empowering each other. Such relationships may promote and facilitate: a) The dissemination of informational intervention resources such as shelters, medical and legal aid through the sharing of information; b) Discussions about the problem of violence against women and how violence affects women and their children. Help women initiate the process of taking action to protect self and children by adopting safety behaviors and to consider seeking an abuse-free life when necessary; c) Creation of a supportive environment to help address feelings of social isolation frequently endorsed by women; (d) Giving and receiving of compassionate support, encouragement, and advice; e) Provision of an informal network to train women in marketable skills, and assistance with seeking employment or become self-employed. Community support groups may be led by women who have experienced abuse or other women who have been trained to support women who experience abuse.

Figure 1.

Needs of women who experience intimate partner violence and those who can offer help: An integrated ecological framework

The second tier of the intervention would include providing women with in-depth one-on-one professional counseling when needed. Professional psychological and legal counseling can be offered by social workers, psychologists, battered women shelters’ staff, and lawyers. In addition, it is very important to educate and train law enforcement officers who respond to women seeking help. Participants in this study expressed frustration about the lack of response offered by police officers, and that their complaints of IPV are minimized or dismissed. Alcalde (2010) provides various examples of this particular dynamic between women and police officers, including police officers adhering to the popular belief that highland and indigenous intimate relationships are inherently violent and that women from the highlands love their partner more if he is violent. Training needs to emphasize that intimate partner violence is not acceptable.

A strength of our proposed two-tiered intervention strategy is that it seeks to empower women at the individual, relationship and community level within the ecological framework. In addition, the proposed strategy is consistent with current World Health Organization recommendations to integrate mental health care in primary care, and use the informal and formal resources of the community and sectors outside the health sector (World Health Organization & World Organization of Family Doctors, 2008). We demonstrate that individuals, couples, communities, and both public and private institutions working in partnership across the nested hierarchical framework are needed to prevent violence against women and mitigate the effects of violence in Perú.

Our finding that leaving may not be the ultimate goal for many women, concurs with those of another study (Peled, Eisikovits, Enosh, & Winstok, 2000). A key characteristic of the two-tiered intervention strategy is to respect each woman’s autonomy in the decision-making process and not to offer a prescription to women. It is each woman’s responsibility and right to make the decision of whether and how to progress towards an abuse-free environment or not. As such, women should be encouraged to consider coexisting issues and multiple options besides leaving the relationship. Women who desire to remain in the relationship can seek referral to social workers and psychologists who can offer relationship counsel and/or couple therapy.

Strengths of our study include participation of women with current and prior experience with IPV. Inclusion of women who have left abusive relationships together with those still in abusive relationships allowed us to capture perceived needs of a group of battered women who are in different phases of change. We reasoned that information gathered from groups of Peruvian women representing experiences across the spectrum of change would be particularly informative for designing interventions likely to meet the needs of women in Lima, Perú. Our study expands the literature to include increased understanding of what abused women may want and need for intervention programs. Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, study participants were recruited from gynecology and family planning clinics and battered women shelters. Consequently, study results may not be generalizable to women who might have been recruited from settings such as mental health institutions, social organizations or governmental agencies. Second, our study design and size did not allow for making comparisons according to participant socio-demographic characteristics, or time spent in abusive relationships. Third, frequency and severity of violence that women experienced were not included in the focus group discussions. These factors could influence the types of interventions that women need or want.

CONCLUSION

We report that victims of IPV need compassionate support and practical interventions such as work skills training, financial support, and assistance with finding employment and housing. These are critical in helping women overcome social, cultural, economic and political barriers that hinder them from taking steps to protect self and children from abuse. We propose the use of a two-tiered intervention strategy that includes community support groups and individual professional counseling designed to meet the diverse needs of women. Our proposed intervention strategy is intended to offer broad coverage, meeting the needs of large populations of women for compassionate support, empowerment, and work skills training, while also offering in-depth specialized professional counseling for individuals requiring intensive support. Respect for each woman’s autonomy in the decision-making process is a key characteristic of this strategy. We recommend that primary, secondary and tertiary violence intervention efforts in Perú that are targeted towards women and men need to address structural factors that contribute to violence against women.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study participants and staff at the hospitals and battered women’s shelter.

Funding

This research was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health, Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities (T37-MD0014490), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD059835).

Contributor Information

Swee May Cripe, Perdana University.

Damarys Espinoza, Ohio State University.

Marta B. Rondon, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and Instituto Peruano de Paternidad Responsable.

Maria Luisa Jimenez, Asociación Civil Proyectos en Salud.

Elena Sanchez, Asociación Civil Proyectos en Salud.

Nely Ojeda, Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal.

Sixto Sanchez, Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas and Asociación Civil Proyectos en Salud.

Michelle A. Williams, Harvard University.

References

- Acevedo M. Battered immigrant Mexican women’s perspectives regarding abuse and help-seeking. Journal of Multicultural Social Work. 2000;8:243–282. [Google Scholar]

- Alcade MC. The Woman in the Violence: Gender, Poverty, and Resistance in Perú. Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Belknap RA, Vandevusse L. Listening sessions with Latinas: documenting life contexts and creating connections. Public Health Nursing. 2010;27(4):337–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesten J. The state and violence against women in Perú: Intersecting inequalities and patriarchal rule. Social Politics. 2012;19(3):361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Boesten J, Fisher M. Special Report. Vol. 310. United States Institute of Peace; 2012. Sexual violence and justice in postconflict Perú; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, Denison JA, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. Ending intimate partner violence: an application of the transtheoretical model. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28(2):122–133. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P, Maman S. The process of ending abuse in intimate relationships: A Qualitative exploration of the transtheoretical model. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:1144–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Cluss PA, Ranieri L, Hawker L, Buranosky R, Dado D, Scholle SH. Health care interventions for intimate partner violence: what women want. Womens Health Issues. 2005;15(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripe SM, Sanchez SE, Sanchez E, Ayala Quintanilla B, Hernandez Alarcon C, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: a pilot intervention program in Lima, Perú. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(11):2054–2076. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defensoría del Pueblo del Perú. Serie Informes de Adjuntía, Informe 003-2010-DP/ADM. 2010. Derecho a la Salud de las Mujeres Víctimas de Violencia: Supervisión a establecimientos de Salud de Lima y Callao; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Dienemann J, Campbell J, Wiederhorn N, Laughon K, Jordan E. A critical pathway for intimate partner violence across the continuum of care. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2003;32(5):594–603. doi: 10.1177/0884217503256943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton M. Empowering and healing the battered women. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Flake DF. Individual, family, and community risk markers for domestic violence in Perú. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(3):353–373. doi: 10.1177/1077801204272129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert B, Abercrombie P, Caspers N, Love C, Bronstone A. How health care providers help battered women: the survivor’s perspective. Women Health. 1999;29(3):115–135. doi: 10.1300/J013v29n03_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert B, Caspers N, Milliken N, Berlin M, Bronstone A, Moe J. Interventions that help victims of domestic violence. A qualitative analysis of physicians’ experiences. Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49(10):889–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Cummings AM, Becerra M, Fernandez MC, Mesa I. Needs and preferences for the prevention of intimate partner violence among Hispanics: A community’s perspective. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2013;34(4):221–235. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL. Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(3):262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL. Working paper (version 2) 2011. What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. Report for the UK Department for International Development. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadiatica e Informatica. Violencia conyugal fisica en el Perú [Physical marital violence in Perú] Lima, Perú: Instituto Nacional de Estadiatica e Informatica; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Klevens J, Shelley G, Clavel-Arcas C, Barney DD, Tobar C, Duran ES, Esparza J. Latinos’ perspectives and experiences with intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(2):141–158. doi: 10.1177/1077801206296980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig N, Lopez-Calva L, Ortiz-Juárez E. Policy Research Paper 6248. 2012. Declining inequality in Latin America in the 2000s: the cases of Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J, Parker B. Abuse during pregnancy: A protocol for prevention and intervention. New York: National March of Dimes Education Foundation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Peled E, Eisikovits Z, Enosh G, Winstok Z. Choice and empowerment for battered women who stay: toward a constructivist model. Soc Work. 2000;45(1):9–25. doi: 10.1093/sw/45.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales MT, Cripe SM, Lam N, Sanchez SE, Sanchez E, Williams MA. Prevalence, types, and pattern of intimate partner violence among pregnant women in Lima, Perú. Violence Against Women. 2009;15(2):224–250. doi: 10.1177/1077801208329387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R, Moracco KE, Goldstein KM, Clark KA. Women’s perspectives on intimate partner violence services: the hope in Pandora’s box. Journal of the American Medical Womens Association. 2003;58(3):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondon MB. From Marianism to terrorism: the many faces of violence against women in Latin America. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2003;6(3):157–163. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper-Hughes N. Death without weeping: The violence of everyday life in Brazil. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Conquest: Sexual violence and American Indian genocide. Cambridge, MA: South End Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1101–1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. World Development Report 2012. Washington, DC, USA: 2012. Gender Equality and Development; p. 458. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Acting on the future: breaking the intergenerational transmission of inequality. UNDP; New York, NY, USA: 2010. Regional Human Development Report for Latin America and the Caribbean 2010; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, & World Organization of Family Doctors; World Health Organization and World Organization of Family Doctors, editor. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. p. 206. [Google Scholar]