Abstract

Openness and self-exploration have been associated with myriad benefits. Within the realm of sexuality, sexual exploration may be 1 facet of openness and self-exploration that yields benefits. Prior literature suggests that such exploration may have benefits for sexual orientation minority persons, though limited research has investigated the benefits of sexual exploration for heterosexuals. The present study used data from 346 adult women (185 exclusively heterosexual, 161 not exclusively heterosexual) to investigate the role of sexual exploration as a mediator between sexual orientation status and positivity toward sex. Results of a structural equation modeling analysis supported mediation of the relationship between sexual orientation and sexual positivity via sexual exploration. Implications for future research and clinical interventions are presented.

Keywords: exploration, positive psychology, sexual orientation, sexual self-concept, sexuality

Historically, much of the research on lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons (i.e., sexual orientation minorities) has focused on better understanding mental health disparities and negative psychosocial outcomes (Vaughan et al., 2014) relative to heterosexual individuals. For example, large bodies of literature have explored the relationship between sexual orientation identity status and suicide (Espelage, Aragon, Birkett, & Koenig, 2008; Mustanski & Liu, 2013; Russell & Joyner, 2001), depression (McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, Xuan, & Conron, 2012; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, Card, & Russell, 2010), substance abuse (Russell, Driscoll, & Truong, 2002), and risky sexual behaviors (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2011). Although previous work has been vital to understanding the pernicious effects of stigma and discrimination on sexual orientation minority persons, a dearth of work has sought to investigate the positive aspects associated with identifying as a sexual orientation minority and related exploration of sexual desires and activities (i.e., sexual self-concept; Winter, 1988) (Vaughan et al., 2014). Nevertheless, recent trends in psychology, such as the positive psychology movement (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), have led to an increased interest in examining the benefits of sexual orientation minority identification and greater sexual exploration, including in therapy (Almario, Riggle, Rostosky, & Alcalde, 2013; Johnson & Zuccarini, 2010; McCarn & Fassinger, 1996; Riggle, Whitman, Olson, Rostosky, & Strong, 2008).

In the area of positive psychology, openness to experience, a major personality dimension (McCrae & Costa, 1987), and a closely related construct, self-exploration, have received a great deal of empirical attention. Although not focused specifically on sexual orientation minority populations, research has shown that higher levels of openness to experience and self-examination are generally correlated with a wide-range of positive psychosocial outcomes. For example, individuals who endorse higher levels of openness to experience show greater resilience in the face of stress (Williams, Rau, Cribbet, & Gunn, 2009), increased memory and everyday functioning (i.e., in older adults) (Gregory, Nettelbeck, & Wilson, 2010), heightened creativity (McCrae, 1987), and decreased racial prejudice (Flynn, 2005). More germane to the current study, Zoeterman and Wright (2014) recently found that sexual orientation minority identity status mediated the positive relation between openness to experience and mental health functioning in a community-based sample of sexual minority adults (R2 = .29). Thus, previous work in the area of positive psychology suggests that openness to experience could prove to be an important resilience factor for sexual orientation minority persons.

Building off the work of Erikson (1968), Worthington, Navarro, Savoy, and Hampton (2008) developed the Measure of Sexual Identity Exploration and Commitment (MoSEIC) to assess various aspects relevant to the process of sexual identity development (subscales include commitment, exploration, uncertainty, and synthesis/integration). Sexual identity development is a process by which an individual comes to recognize his or her “sexual values, sexual needs, preferred modes of sexual expression, preferences for characteristics of sexual partners, and preferences for sexual activities, as well as recognition and acceptance of sexual orientation identity” (Worthington, 2004, p. 742). Importantly, Worthington et al. (2008) created the MoSEIC to assess sexual identity development across a variety of sexual orientation identity groups, including heterosexual persons. Sexual orientation identity is conceptualized as an identity status that is achieved through active exploration and not inherently limited to the experiences of nonexclusively heterosexual persons. The development and validation of the MoSEIC scale has provided initial support for the role of sexual exploration in facilitating the identity development process.

Benefits of Sexual Identity Exploration for Nonheterosexuals

Researchers examining the process of sexual identity development acknowledge that heterosexuality is often seen as the normative or ‘default’ sexual identity. Thus, a majority of sexual identity development models have focused on the experiences of nonheterosexual persons (Balsam & Mohr, 2007; Cass, 1979; Fox, 2003; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000), primarily concerned with understanding the particular challenges that sexual orientation minorities face during sexual identity development. These challenges are thought to arise, in part, from expectations and experiences of stigma, ostracism, and violence (Meyer, 1995). For example, in a sample of 613 lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals, Balsam and Mohr (2007) found that reports of heightened internalized homonegativity, stigma sensitivity, and identity superiority (i.e., factors thought to reflect problematic sexual identity development) were independently and negatively associated with psychological well-being (r = −.22, r = −.31, and r = −.13 for homonegativity, stigma sensitivity, and identity superiority, respectively; Balsam & Mohr, 2007).

The few available studies that have attempted to identify corollaries of adaptive functioning, derived from the sexual identity development process, suggest positive associations among sexual identity exploration, psychosocial adjustment, and psychological well-being. For example, among sexual orientation minority persons, higher levels of positivity regarding sexual identity status were associated with higher levels of self-esteem (adjusting for age, education, income, location, and relationship status; for women r = .49; for men, r =.48) and life satisfaction (for women r =.45; for men, r =.42) (Luhtanen, 2002). More recently, Zoeterman and Wright (2014) investigated the impact of higher levels of openness to experience on the mental health functioning of sexual orientation minority adults. Zoesterman and Wright found that a more well-developed sexual identity fully accounted for the positive relation between openness to experience and mental health functioning, such that openness to experience positively related to a more well-developed sexual orientation identity, which, in turn, was associated with better mental health functioning (R2 =.28). The link between positive sexual identity development and psychological adjustment has also been supported among sexual minority individuals of various ethnic and racial backgrounds (i.e., White, Black, Latino) (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004). Taken together, findings from the extant literature suggest that greater sexual exploration, as reflected by greater openness to experience, may facilitate sexual identity development and positive mental health functioning more broadly.

Benefits of Sexual Identity Exploration for Heterosexual Individuals

Although prioritizing the study of the sexual identity development process has contributed much to a better understanding of how these processes impact nonexclusively heterosexual populations, an unfortunate consequence is that relatively less attention has been paid to examining the sexual identity development of exclusively heterosexual individuals. Eliason (1995) provided a qualitative account of sexual identity formation among heterosexual undergraduate men and women. Many heterosexual individuals described their identity formation process in a way consistent with the concept of identity foreclosure, which was described by Marcia (1966) as a state in which an individual has accepted an identity imposed by culture, family, or others, without having explored other options (Eliason, 1995). Moreover, many heterosexual young adults disclosed that they had not thoughtfully explored their sexual identity, believed that an outside force had made them heterosexual, assumed that their sexual orientation was innate, or struggled to articulate how heterosexuality affected their lives (Eliason, 1995). Consistent with Eliason’s (1995) findings, heterosexual persons are often found to engage in less questioning of their sexual orientation identity than nonheterosexual persons, which may be readily explained in the context of compulsory heterosexuality in which heterosexuality is assumed as the “norm” (Eliason, 1995; Konik & Stewart, 2004). Nevertheless, a heterosexual identity does not preclude individuals from engagement in sexual exploration and efforts to integrate their sexual orientation into their sexual self-concept. Indeed, there is reason to believe that such explorations may have positive effects for a variety of sexual identity groups (somewhat analogous to modern models of racial identity development that include racial majority persons and development of nonracist White identity, Helms, 1993).

Among heterosexual-identified women, previous work examining active sexual identity exploration has focused on the evaluation of both same-sex and other-sex sexual experiences (Morgan & Thompson, 2011). Empirical findings indicate that heterosexual-identified individuals who engage in sexual identity exploration also enjoy benefits with regard to their sexual self-concept and overall identity development. For example, among undergraduate heterosexual-identified women (n = 293), sexual identity exploration has been positively linked to sexual well-being (Muise, Preyde, Maitland, & Milhausen, 2010). Thus, there is reason to expect that greater sexual identity exploration is also beneficial to the psychosocial functioning of heterosexual individuals.

Existing research indicates that sexual orientation may be linked to greater sexual positivity. An individual’s sexual orientation is informed, in part, by her self-identification (i.e., self-labeling of sexual identity), degree of opposite- versus same-sex sexual desire (i.e., sexual attraction), and degree of opposite- versus same-sex sexual activity (i.e., sexual behavior; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). Qualitative data from sexual minority individuals (Galupo, Davis, Grynkiewicz, & Mitchell, 2014) support that a person’s self-ascribed sexual identity is essential for contemplating and defining sexual orientation. Indeed, sexual orientation minority persons viewed their current sexual identity as “primary over current and past experience that might otherwise be interpreted as ‘contradictory’” (Galupo et al., 2014, p. 16) and stated that they used multiple aspects of their sexual self-concept when exploring and labeling dimensions of their sexual orientation. Research also suggests that the link between sexual identity status and sexual positivity may be mediated by exploration of various aspects of sexual desires and needs, which would indicate that such self-explorations may be beneficial in general, regardless of a person’s sexual orientation. The present study aimed to assess whether higher levels of exploration of sexual identity would mediate the association between lifetime sexual orientation minority status and greater positivity toward sex. Specifically, we hypothesized that a significant indirect effect, from sexual orientation identity status, through sexual identity exploration, to sexual positivity, would be supported by the data.

Method

Participants

The original sample consisted of 351 adult women. One participant’s data were removed from analyses, as she indicated no sexual interest, and four others’ data were removed because of large amounts of missing items (i.e., across multiple measures). Thus, the final sample used in the current analysis was 346 women. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 30 years (M = 20.96, SD = 2.93, Mdn = 20). With regard to sexual orientation, 185 participants (53%) had identified as exclusively heterosexual throughout their entire lives, whereas 161 (47%) had identified as nonexclusively heterosexual (e.g., primarily heterosexual, exclusively homosexual) at some point in their lives. Regarding race, participants were allowed to self-identity as many options as applied to them from multiple categories; 266 participants (77%) identified as White, 31 (9%) as Black, 10 (3%) as Asian, and 8 (3%) as Hispanic only, whereas 25 participants (7%) identified as multiracial (7 as White and American Indian; 5 as White and Asian; 1 as White, Asian, and Hispanic; 5 as White and Black; 6 as White and Hispanic; 1 as Hispanic and Black).

Procedure

Community and student participants were recruited from the fall of 2010 to the spring of 2013 into an online survey study examining how aspects of women’s sexuality contribute to their alcohol consumption and misuse. Psychology students at a Midwestern university were invited to enroll in a study examining “female sexuality and alcohol use.” Community participants were recruited through distributions of campus-wide email notices, advertisements in local newspapers, posted flyers in local businesses, and snowball sampling techniques. Women indicating interest in the survey were administered a brief telephone screening to determine eligibility. Eligible persons (a) self-identified as women, (b) were between the ages of 18 and 30 years (inclusive), (c) were English-speaking, and (d) reported consuming at least one alcoholic beverage in the previous 3 months. Eligible participants were e-mailed a link and a password to a confidential online survey, which allowed for consent and contained an embedded random-code identifier for reimbursement purposes. Students received course credit in return for their participation. Eligible community participants received a $25 gift certificate to Amazon.com in exchange for their time. All relevant federal and institutional research ethical standards were met with regard to the treatment of participants, and approval from a university human subjects review board was obtained for this study.

Measures

Lifetime sexual identity status

When responding to an item asking, “In the past, how would you have described your sexual orientation?,” participants had the opportunity to select multiple options to indicate their lifetime sexual orientation statuses (exclusively heterosexual primarily heterosexual, equally homosexual and heterosexual, primarily homosexual, exclusively homosexual, queer, questioning) and an option was available to write in an unlisted sexual orientation (i.e., “pansexual,” “heterosomething”). For the present study, a dichotomous variable was created to denote lifetime sexual identity status. Women who identified as exclusively heterosexual throughout their entire lives were coded as the reference group. Women who, at some point in their lives, had identified as a nonexclusively heterosexual identity were coded as sexual orientation minorities.

Measure of Sexual Identity Exploration and Commitment (MoSIEC; Worthington et al., 2008)

The Exploration subscale of the MoSIEC (MoSIEC-EX) is an 8-item subscale from the larger MoSIEC measure that assesses the degree to which persons report openness to exploring their own sexual needs and desires (e.g., “My sexual values will always be open to exploration,” “I can see myself trying new ways of expressing myself sexually in the future”). Responses to the items are made on a six-point scale (1 = very uncharacteristic of me, 6 = very characteristic of me). During development, responses to the measure demonstrated good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .85 to .87 among multiple samples of several hundred individuals, of differing sexual orientation identities, racial/ethnic backgrounds, and ages, and collected via University class survey administration, LGBT listservs, LGBT student groups, and public-access Internet sites for psychology research) and showed negative associations with religiosity and sexual conservativism as well as positive associations with sexual assertiveness. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for responses to the items, obtained using available item analysis (Parent, 2013), was .89.

Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire (Snell, Fisher, & Walters, 1993)

The Sexual Self-efficacy, Sexual Consciousness, Sexual Motivation, and Sexual Self-schema sub-scales of the MSSCQ (MSSCQ-SE, -SC, -MO, and -SS, respectively) are four subscales of the MSSCQ that measure positive constructs relevant to the sexual self-concept. MSSCQ-SE assesses belief that one is capable of meeting one’s sexual needs (e.g., “I have the ability to take care of any sexual needs and desires that I may have”). The MSSCQ-SC assesses greater awareness regarding and reflecting on one’s sexuality (e.g., “I am very aware of my sexual feelings and needs”). The MSSCQ-MO assesses an approach orientation toward meeting one’s sexual needs (e.g., “I’m motivated to devote time and effort to sex”). The MSSCQ-SS assesses the presence of organizing cognitive frameworks for understanding one’s sexuality (e.g., “Not only would I be a good sexual partner, but it’s quite important to me that I be a good sexual partner”). Responses to items on the four subscales are made on a 5-point, Likert-type scale (1 = not at all characteristic of me, 5 = very characteristic of me). In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas, using available item analysis (Parent, 2013), were good for each of the subscales: .88 (-SE), .80 (-SC), .91 (-MO), and .82 (-SS).

Results

Correlations among variables for both heterosexual and non-heterosexual women are presented in Table 1. Mplus v7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010), a versatile structural equation modeling software platform, was used to analyze the data with full-information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors to allow for analysis of data containing missing values. Lifetime sexual orientation minority status (coded dichotomously as exclusively heterosexual [0] versus. any sexual minority identity [1] in one’s lifetime) and scores on the MoSEIC-Ex subscale were included in regression models as manifest variables. Scores on each respective MSSCQ subscale were modeled as indicators of a single latent variable, herein referred to as Sexual Positivity. The covariance between MSSCQ-CO and -EF residual errors was freely estimated due to evidence (supported by nested model comparisons) of a method factor for those two subscales (χ2 = 23.26, df = 1, p < .001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Statistic | Explore | SE | SC | SM | SS | Exclusively heterosexual

|

Nonheterosexual

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||||

| Explore | .39*** | .38*** | .49*** | .32*** | 3.14 | 1.29 | 4.32 | 1.05 | |

| SE | .22** | .66*** | .65*** | .53*** | 3.66 | 1.03 | 3.91 | 0.94 | |

| SC | .32*** | .67*** | .51*** | .44*** | 3.97 | 0.77 | 4.19 | 0.74 | |

| SM | .46*** | .43*** | .50*** | .54*** | 3.10 | 1.19 | 3.65 | 1.02 | |

| SS | .26*** | .51*** | .50*** | .46*** | 4.26 | 0.78 | 4.40 | 0.73 | |

Note. Correlations for exclusively heterosexual women are presented below the diagonal. Correlations for non-exclusively heterosexual women are presented above the diagonal. SE = Self-efficacy; SC = Consciousness; SM = Motivation; SS = Self-Schema.

p < .01.

p < .001.

First, a measurement model (i.e., covariances freed among the three primary variables) was assessed. Goodness of fit statistics indicated that the measurement model fit the data reasonably well, χ2(7) = 23.50, p < .01, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.083 (95% CI = 0.047, 0.120), SRMR = 0.034 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All factor loadings and covariances were significant at p < .001.

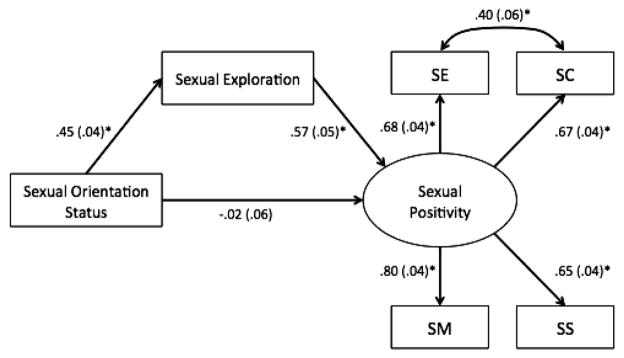

Given evidence that the measurement model was a good fit to the data, the hypothesized structural model was examined. Paths were constrained as shown in Figure 1. The model was run with 5,000 bootstrapped samples to obtain model-based confidence intervals for indirect effects. This model also fit the data reasonably well, χ2(7) = 25.23, p < .001, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.087 (95% CI = 0.052, 0.125), SRMR = 0.035; R2 = 0.32. All factor loadings were significant at p < .001; estimated path coefficients are displayed in Figure 1. Consistent with hypotheses, there was a significant indirect effect from lifetime sexual orientation identity status, through sexual exploration, to sexual positivity; β = 0.51, 95% bias-corrected CI = 0.38, 0.65; SE = 0.07; p < .001. The indirect effect was such that women who had ever indicated a nonexclusively heterosexual identity in their past reported higher levels of sexual exploration; these higher levels of sexual exploration were, in turn, related to higher levels of sexual positivity, as reflected by higher sexual self-efficacy, greater sexual consciousness, elevated sexual motivation, and a more organized sexual self-schema.1

Figure 1.

Values represent the standardized coefficients and standard error (in parentheses). SE = Self-efficacy; SC = Consciousness; SM = Motivation; SS = Self-Schema. * p < .001.

Discussion

The results of the present study support the hypothesis that sexual exploration could account for the association between sexual orientation minority identity and sexual positivity. The present study provides an account of why a sexual orientation minority identity might benefit the sexual self-concept (indeed, sexual orientation minority participants reported higher scores on all variables assessed in the present study; for sexual exploration, d = 1.00; for Sexual self-efficacy, d = .99; for Sexual Consciousness, d = .76; for Sexual Motivation, d = 1.11; for Sexual self-schema, d = .76). Specifically, our findings suggest that greater sexual exploration, which may be considered part and parcel of sexual identity development, can account for these types of positive associations. Given that almost half of women in the U.S. report sexual dysfunction (Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, 1999), we assert that even heterosexual-identified women who engage in such personal explorations may also experience the psychological benefits that they can entail.

These results have implications for future research examining the positive aspects of sexual identity development processes. First, future work should attempt to replicate and extend our results with alternative adaptive outcomes, such as cognitive flexibility. Second, this work highlights the need for researchers to further consider identity-relevant variables, such as sexual exploration, to potentially account for relations between sexual orientation status and psychological well-being. Third, in addition to identity-related variables, research should continue investigating other variables theoretically relevant to positive sexuality. For example, variables reflecting levels of LGBT community involvement, or particular patterns of sexual history and behavior, might explain why some sexual orientation minorities experience positive psychosocial outcomes, whereas others do not. Finally, it is important that this research also be extended to samples of men to assess the hypothesized associations among heterosexual and sexual minority men.

With regard to counseling and psychotherapy with female clients, the present results speak to the potential benefit of engaging women in discussions of their sexual self-concepts and facilitating a better understanding of themselves as sexual beings, regardless of their current or past sexual orientation. Although acknowledging and honoring the client as a sexual being is an underpinning of feminist therapy (Chester & Bretherton, 2001), such interventions could also be used within culturally sensitive cognitive–behavioral or interpersonal therapies. Such treatment approaches may benefit from additional research on the psychosexual benefits of feminist-based therapy.

The results of the present study must be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, the data collected were cross-sectional and thus causation cannot be inferred from our mediational findings; indeed, it is possible that a reciprocal relationship exists between sexual exploration and sexual positivity. Additional research could provide evidence of causal processes through experimental studies or, as mentioned above, in examining the effects of feminist-based therapy. Second, the present study used data from a sample of primarily White young adult women, and results might not necessarily generalize to other populations. In particular, it would be important to assess whether the benefits of sexual exploration persist, particularly in social or cultural contexts that have relatively less accepting attitudes toward sexual exploration and same-sex sexuality, generally. Despite these limitations, our findings extend the literature on the benefits of sexual exploration and offer preliminary support that such self-explorations may be beneficial to the sexual self-concepts of women.

Footnotes

We tested two models that used sexual orientation response options to create dummy-coded dichotomous variables, assessing for differences between sexual orientation minority subgroups. The first model distinguished participants as exclusively heterosexual, primarily heterosexual, and a group containing all other participants. A second, independent model distinguished participants as exclusively heterosexual, primarily heterosexual, bisexual, and a final group comprising primarily and exclusively lesbian participants (participants who selected “other” were not included in this analysis). In both alternative models, the model fit the data well, and similar patterns and conclusions emerged as in the main analysis. In both models, nested model comparisons, constraining paths from the dummy-coded variables to sexual exploration variable as opposed to allowing them to be freely estimated, did not significantly reduce model fit, suggesting that the associations were not different across sexual orientation subgroups.

References

- Almario M, Riggle ED, Rostosky SS, Alcalde MC. Positive themes in LGBT self-identities in Spanish-speaking countries. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation. 2013;2:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Mohr JJ. Adaptation to sexual orientation stigma: A comparison of bisexual and lesbian/gay adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:306–319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.306. [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester A, Bretherton D. What makes feminist counselling feminist? Feminism & Psychology. 2001;11:527–545. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959353501011004006. [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ. Accounts of sexual identity formation in heterosexual students. Sex Roles. 1995;32:821–834. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01560191. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Aragon SR, Birkett M, Koenig BW. Homophobic teasing, psychological outcomes, and sexual orientation among high school students: What influence do parents and schools have? School Psychology Review. 2008;37:202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn FJ. Having an open mind: The impact of openness to experience on interracial attitudes and impression formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:816–826. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.816. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RC. Bisexual identities. In: Garnets L, Kimmel D, editors. Psychological perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual experiences. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2003. pp. 86–127. [Google Scholar]

- Galupo MP, Davis KS, Grynkiewicz AL, Mitchell RC. Conceptualization of sexual orientation identity among sexual minorities: Patterns across sexual and gender identity. Journal of Bisexuality. 2014;14:433–456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2014.933466. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory T, Nettelbeck T, Wilson C. Openness to experience, intelligence, and successful ageing. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:895–899. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.017. [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE. Black and White racial identity: Theory, research and practice. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Zuccarini D. Integrating sex and attachment in emotionally focused couple therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2010;36:431–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00155.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konik J, Stewart A. Sexual identity development in the context of compulsory heterosexuality. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:815–844. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00281.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen RK. Identity, stigma management, and well-being: A comparison of lesbians/bisexual women and gay/bisexual men. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2002;7:85–100. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n01_06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J155v07n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;3:551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarn SR, Fassinger RE. Revisioning sexual minority identity formation: A new model of lesbian identity and its implications for counseling and research. The Counseling Psychologist. 1996;24:508–534. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000096243011. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR. Creativity, divergent thinking, and openness to experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:1258–1265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1258. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:81–90. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Xuan Z, Conron KJ. Disproportionate exposure to early-life adversity and sexual orientation disparities in psychiatric morbidity. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36:645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.07.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:38–56. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2137286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, Fassinger RE. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2000;33:66–90. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EM, Thompson EM. Processes of sexual orientation questioning among heterosexual women. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48:16–28. doi: 10.1080/00224490903370594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224490903370594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muise A, Preyde M, Maitland SB, Milhausen RR. Sexual identity and sexual well-being in female heterosexual university students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:915–925. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9492-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Liu RT. A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:437–448. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0013-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Moderators of the relationship between internalized homophobia and risky sexual behavior in men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9573-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent MC. Handling item-level missing data: Simpler is just as good. The Counseling Psychologist. 2013;41:568–600. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000012445176. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle ED, Whitman JS, Olson A, Rostosky SS, Strong S. The positive aspects of being a lesbian or gay man. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:210–217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.210. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Ethnic/racial differences in the coming-out process of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A comparison of sexual identity development over time. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:215–228. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Driscoll AK, Truong N. Adolescent same-sex romantic attractions and relationships: Implications for substance use and abuse. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:198–202. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.198. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology. An introduction. American Psychologist. 2000;55:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE, Jr, Fisher TD, Walters AS. The Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire: An objective self-report measure of psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality. Annals of Sex Research. 1993;6:27–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00849744. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: School victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1580–1589. doi: 10.1037/a0020705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan MD, Miles J, Parent MC, Lee HS, Tilghman JD, Prokhorets S. A content analysis of LGBT-themed positive psychology articles. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1:313–324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000060. [Google Scholar]

- Williams PG, Rau HK, Cribbet MR, Gunn HE. Openness to experience and stress regulation. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43:777–784. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.06.003. [Google Scholar]

- Winter L. The role of sexual self-concept in the use of contraceptives. Family Planning Perspectives. 1988;20:123–127. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2135700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington RL. Sexual identity, sexual orientation, religious identity, and change: Is it possible to depolarize the debate? The Counseling Psychologist. 2004;32:741–749. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000004267566. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington RL, Navarro RL, Savoy HB, Hampton D. Development, reliability, and validity of the Measure of Sexual Identity Exploration and Commitment (MOSIEC) Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:22–33. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeterman SE, Wright AJ. The role of openness to experience and sexual identity formation in LGB individuals: Implications for mental health. Journal of Homosexuality. 2014;61:334–353. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2013.839919. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.839919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]