Abstract

Introduction

We examined circadian periodicity of atrial tachyarrhythmias (AT/AF) in a large group of patients with implantable devices, which allow continuous collection of the event data over prolonged periods of time.

Methods and Results

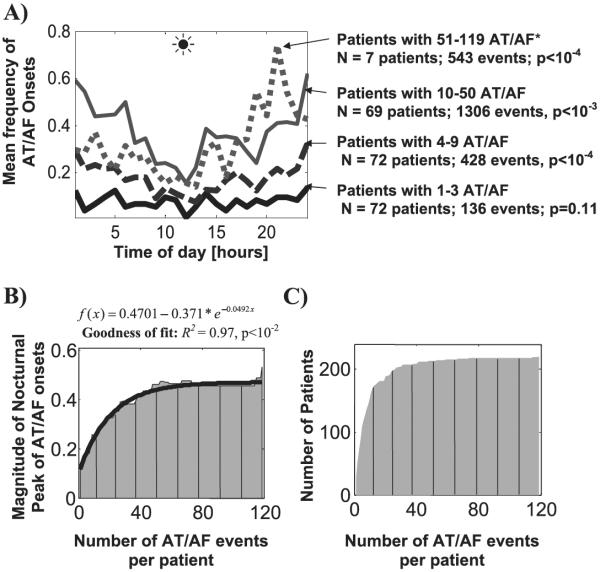

A total of 16,130 AT/AF events were recorded in 236 patients (age: 63 ± 12 years, 27% female, 90% had a history of cardiovascular disease, 33% ischemic, LVEF: 49 ± 18%) over a period of 12 months. To exclude interactions with therapy, the patterns of arrhythmia occurrence were examined for all events and for those episodes that were preceded by at least 1, 6, and 24 hours of sinus rhythm. To prevent biasing toward patients with more frequent episodes, the patterns of AT/AF onset were analyzed both in absolute and patient-normalized (i.e., divided by the total number of events in each patient) units per hour per patient and then summarized for the entire group. In patients with <4 AT/AF events, the onset times were randomly distributed over 24-hour period. However, as the number of AT/AF events increased, a nocturnal pattern of occurrence (determined by the occurrence of a trough around noon) gradually emerged and became highly statistically significant (P < 10−4). The magnitude of nocturnal peak of AT/AF events was well explained by a single-exponential function (R2 = 0.97, P < 10−2).

Conclusion

Patients with more frequent atrial tachyarrhythmias are more likely to develop AT/AF at night. Knowledge of patient-specific circadian patterns of arrhythmia occurrence can be useful for personalized management of individuals with significant arrhythmia burden.

Keywords: atrial tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, autonomic nervous system, circadian, pacemaker

Introduction

All atrial tachyarrhythmias (atrial tachycardia/flutter and atrial fibrillation, AT/AF) are not created equal; they arise in various parts of atrial chambers interspersed by complex neurovascular structures, islands of fibrosis, and suddenly “erupting” triggers of enhanced automaticity.1,2 A variety of the 24-hour patterns of AT/AF initiation (including random, diurnal, nocturnal, and multimodal types) has been reported in different populations, but its principal mechanisms remain unexplained.3–13 The uncertainty, in a large part, stems from the technical difficulties of continuous data collection over prolonged time required to capture arrhythmic events (which can be rare or asymptomatic) and processing such prodigious amounts of data. Most studies of the circadian patterns of AT/AF have been limited to the information collected from ambulatory (Holter) ECG data5 or emergency phone calls.3 Although these investigations have provided important insights into the incidence of AT/AF, they could not systematically examine the determinants of various circadian patterns, due to the inability of tracking multiple arrhythmic events over prolonged periods of time. More recently, advances in the implantable device technology have opened a window of opportunity for long-term continuous data collection and accurate tracking of arrhythmic events.4

Thus, the goal of this study was to examine both the circadian periodicity of AT/AF and its determinants in a large cohort of patients with implantable devices. A better understanding of such determinants could be useful for optimization of arrhythmia prevention and management and may provide the basis for development of more efficient, patient-specific approaches.

Methods

Study Population and Patient Characteristics

Data for this study were obtained from the Jewel AF study that has been described in detail.14–17 Briefly, this multicenter study was conducted in 60 centers. A Jewel 7250 AF ICD (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was implanted in patients who had a clinical indication for the implantation of a ventricular ICD and at least 2 documented episodes of (symptomatic or asymptomatic) AF and/or AT in the year before implantation, with a 12-lead ECG documentation of at least 1 episode. Patients with chronic AF (unable to sustain sinus rhythm) were excluded. Ventricular therapies were enabled in all patients. Patients were followed up with routine device interrogations for up to 3 years; changes in antiarrhythmic drug therapy during the study period were discouraged.

Atrial Arrhythmia Detection and Discrimination Algorithm

The detection and discrimination algorithm implemented in the Jewel 7250 AF ICD has been described in detail.14–17 In short, the device discriminates AT from AF on the basis of 2 programmable detection zones, which may overlap. The nominal (factory) settings for the device include: (i) the 12-beat median atrial cycle length (ACL) for AF and AT equal to 100–270 ms and 170–320 ms, respectively; and (ii) the ACL regularity within the overlapping zone of 170–270 ms (i.e., the diagnosis of AT or AF is made if ACL is regular or irregular, respectively). These threshold values could be changed at the discretion of the treating physician.

Data Analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics that were available for the studied patient population are shown in Table 1. To examine systematically the impact of these variables on the circadian patterns of AT/AF initiation, multiple analyses were required in the subsets obtained using various combinations of these patient characteristics. Clearly, the large number of possible subsets that could be generated using various cutoff values of these variables makes manual analysis unfeasible. In particular, dichotomizing the first 7 demographic and clinical variables (e.g., males vs females) would generate 128 subsets; furthermore, with multiple cutoff values (e.g., different frequencies of AT/AF events) the number of possible subsets would be even larger.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients with AT/AF Events

| Clinical Characteristics | All Patients with AT/AF Events | Patients with AT/AF Preceded by ≥24 hours of SR§ | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (patients) | 236 | 220 | |

| Age (years) | 63 ± 12 | 63 ± 12 | 0.7 |

| Gender female (%) | 27% | 26% | 0.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29 ± 6 | 29 ± 6 | 1.0 |

| History of cardiovascular disease (%) | 90% | 90% | 1.0 |

| Ischemic heart disease (%) | 33% | 33% | 0.8 |

| LVEF (%) | 49 ± 18% | 49 ± 18% | 1.0 |

| AT/AF events | |||

| Total | 16, 130 | 2413 | |

| Mean/per patient ± std | 70 ± 111 | 11 ± 16 | |

| Median/25–75% range | 25/9–82 | 6/3–12 | |

| Follow-up (months) | 0.7 | ||

| Mean ± std | 12 ± 9 | 12 ± 9 | |

| Median/25–75% range | 11/5–18 | 10/5–18 | |

| Medications (%) | |||

| Beta-blockers (all types combined) | 89 | 90 | 1.0 |

| Antiarrhythmic and rate control (All types combined) | 100 | 100 | 1.0 |

| Other | 92 | 91 | 1.0 |

SR = sinus rhythm.

All patients versus patients with events preceded by ≥24 hours of SR.

To obviate this problem, we have developed a suite of software routines (SQL, Microsoft, Redmond, WA; Matlab, Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) that allows computationally efficient generation and systematic analysis of various data subsets. Monte Carlo simulations (N = 10,000 simulations for each statistical test) were performed to eliminate false-positive findings due to multiple comparisons. The software has been thoroughly tested using multiple side-by-side comparisons of both automatically and manually selected subsets using pairwise differences between the corresponding data entries. These tests were performed in 35 subsets (for some, randomly selected variables shown in Table 1). In all tests, the subsets selected using automatic and manual procedures have been found to be identical.

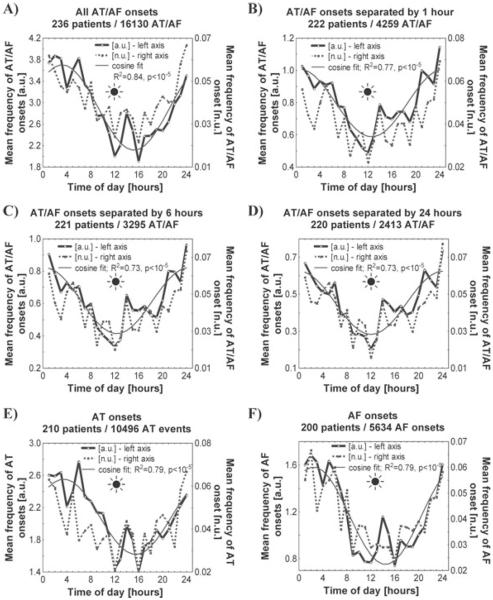

To prevent biasing of the results toward patients with more frequent episodes, the patterns of AF onset were analyzed both in absolute (number of AT/AF events per hour) and patient-normalized units (number of AT/AF per hour divided by the total number of AT/AF events in each patient over the follow-up period) in each patient and then summarized for the entire group, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The mean frequency of onset times of all paroxysmal AT/AF events (panel A), events separated by ≥24 hours (panel B), ≥6 hours (panel C) and ≥1 hour of sinus rhythm (panel D); the mean frequency of the onset times of AT events (panel E) and AF events (panel F). To prevent biasing toward patients with more frequent episodes, the mean frequency of the events over the follow-up period was estimated in 1-hour intervals both in absolute (mean number of AT/AF events per hour [a.u.]) and patient-normalized units (number of AT/AF per hour divided by the total number of AT/AF events in each patient [n.u.]). A cosine function f (x) = a* cos(2πx/24 + b) + c with the coefficients a, b, and c determined using nonlinear least squares (Gauss-Newton) has been fitted to the mean number of AT/AF events per hour (a.u.). The goodness of fit was estimated using R2, the statistical significance of the circadian patterns was tested using a zero-amplitude test. A sun symbol indicates noontime.

For each binary variable shown in Table 1, the dataset was dichotomized into the subsets of patients with and without the corresponding variable (e.g., males vs females), and the circadian patterns of AT/AF in both subsets were compared. For nonbinary variables (e.g., age, LVEF), the data sets were divided into the 2 subsets (above and below the mean value), then into the 4 subsets (corresponding to 25, 50, 75, and 100% of the dataset), and finally into the 10% bins (e.g., LVEF < 50, 40, and 30%), and the circadian patterns of AT/AF were compared for all these subsets.

To examine the impact of AT/AF frequency, the analysis was performed in (i) the entire dataset and (ii) the subsets of patients with different cutoff values for arrhythmia frequency (<2, 3, 4,…, maximum number of AT/AF per patient). Similarly, to estimate the impact of AT/AF duration, the analysis was performed in the subsets of AT/AF events of various durations (<30 seconds, ≥30 seconds, >1 minutes, >1 hour, >2 hours, etc.). In addition, the impact of medications was examined by performing the analyses in (i) the entire dataset, (ii) the subset of patients who had no changes in any medications during the follow-up period, and (iii) the subsets of patients with/without β-blockers, as well as each medication listed in Table 1.

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). The presence and statistical significance of a 24-hour periodicity was tested using the cosinor analysis:18 f (x) = a* cos(2πx/24 + b) + c where the coefficients a, b, and c were computed using the nonlinear least-squares (Gauss–Newton) method. The goodness of fit was estimated using R2, the statistical significance of the model (P-value) was tested using a zero-amplitude test.18 To minimize the effects of distributions that are different from normal, the comparisons of independent subgroups were carried out using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test. Data were presented as the number of patients (% total) or as mean±standard deviation (SD). In addition, the median values and 25–75% ranges are shown for nonparametric tests (which minimize possible biases for data distributions that are different from normal). Fisher's exact test was used to compare the number of patients on each medication in the studied group and in all patients with AT/AF (Table 1). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 16,130 AT/AF events were recorded in 236 patients (age: 63 ± 12 years, 27% female, 90% had a history of cardiovascular disease, 33% ischemic, LVEF: 49 ± 18%) with implantable devices over a period of 12 ± 9 months (Table 1). There were no differences in clinical or demographic characteristics between the study group and all patients with AT/AF events (Table 1). The proportions of AT and AF events (classified by the device using the rate and regularity criteria15) were 65% and 35%; they occurred in 210 and 200 patients, respectively.

Patterns of Initiation of Paroxysmal Atrial Tachyarrhythmias

To assess the influence of the device's therapy on the pattern of AT/AF initiation, we compared the onset times for all 16,536 arrhythmic events and for those that were preceded by ≥1 hour, ≥6 hours or ≥24 hours of sinus rhythm (Fig. 1). In all these groups, paroxysmal AT/AF occurred 2–3 times more frequently at night than during the daytime, peaking around midnight and decreasing to a minimum around noon. The patterns of nocturnal predominance of AT/AF initiation (determined by the occurrence of a trough around noon) were similar when the mean frequency of the event initiation was examined in absolute (a.u.) and patient-normalized units to control for potential biasing toward patients with more frequent events. The patterns of AT/AF initiation could be approximated well by a single-cosine function (R2 ≥ 0.73, P < 10−5) with a 24-hour period, further supporting the significance of 24-hour rhythmicity in the incidence of arrhythmic events. The patterns of arrhythmia initiation were similar for the subgroups of events classified by the device as AT and AF (Fig. 1; panels E, F).

Because changes in antiarrhythmic drug therapy and multiple sequential drug use could affect event rates, the patterns of AT/AF were also analyzed in a subset of patients who did not have changes in medication during the follow-up. The pattern of AT/AF events in this subgroup was similar to that in Fig. 1, confirming that the presence of nocturnal peak was unrelated to specific medications (data not shown).

The Impact of Arrhythmia Burden

To exclude interactions with device's therapy, 2413 AT/AF events that were preceded by at least 24 hours of sinus rhythm were selected for this subanalysis. The impact of AT/AF burden has been examined systematically for all subsets of patients with different AT/AF frequencies (<2, 3, 4, …, the maximum number of AT/AF per patient), as shown in Figure 2. In patients with <4 AT/AF events, the onset times were randomly distributed over 24-hour period (72 patients, Fig. 2A). However, as the number of AT/AF events increased, a nocturnal peak of arrhythmia initiation gradually emerged and became highly statistically significant (P<10−4). This pattern was observed both in absolute and patient-normalized units. The magnitude of the nocturnal peak of AT/AF initiation was well explained by a single exponential function (R2 = 0.97; P < 10−2; Fig. 2B), with a steep, near-linear increase between 4 and 50 arrhythmic events (R2 = 0.86, P < 10−5 for a linear fit in that region of the graph). We note that the maximum number of AT/AF events per patient in the studied dataset was 119; however, only 7 patients had >50 AT/AF events (543 events for all 7 patients; Fig. 2C), which limited more detailed analysis of the circadian patterns in the subgroup of patients with >50 arrhythmic events.

Figure 2.

Panel A: the mean frequency of the onset time of paroxysmal AT/AF grouped in 1-hour intervals over 24-hour period in absolute (mean number of AT/AF events per hour) units. The onset times for patients with 1–3 AT/AF events were distributed randomly over 24-hour interval. However, as the number of events gradually increased, a nocturnal peak slowly emerged and became highly pronounced. *For patients with 50–119 events, each point on the graph of the AT/AF frequency was rescaled (divided by 10), to show these data in the same reference frame together with the other patient groups which had lower event frequency. Panel B: the magnitude of the nocturnal peak of AT/AF onset times for each tracing shown in Panel A (i.e., range of circadian variation = max – min number of events) was approximated well (R2 = 0.97, P<10−2) by a single exponential function shown at the top. Panel C: the number of AT/AF events versus the number of patients in the studied group. The P-values were calculated using the cosinor analysis and a zero-amplitude test (see Figure 1 legend for details).

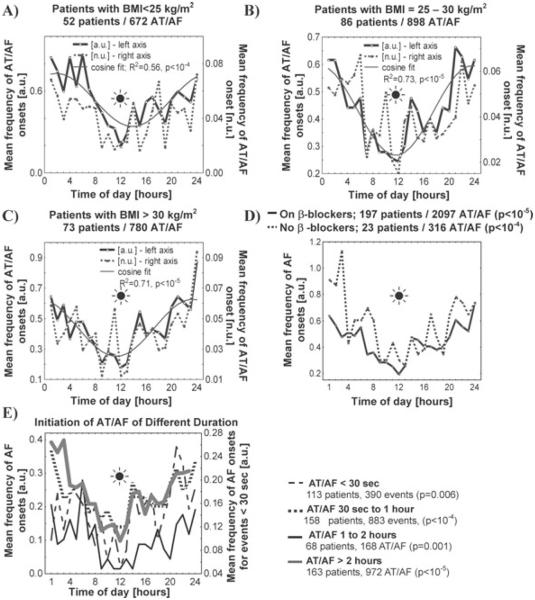

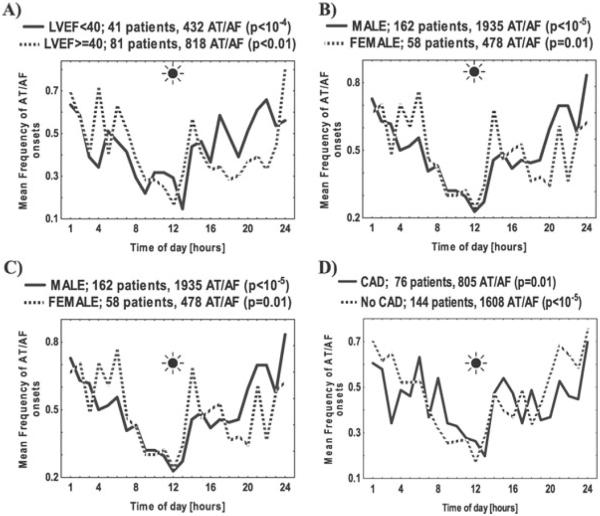

The Impact of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The circadian patterns of AT/AF initiation were examined in the subsets of patients selected using the demographic and clinical characteristics listed in Table 1. A circadian pattern of arrhythmia initiation was present in patients who were of normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2; Fig. 3), those who were overweight (BMI = 25–30 kg/m2), and those who were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2). This pattern was statistically significant both in patients with preserved and reduced systolic function (Fig. 4A). The circadian pattern was preserved in both males and females (P < 10−5 and P = 0.01, respectively, Fig. 4B).

Figure 3.

Patterns of initiation of AT/AF events in patients who were of normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), who were overweight (BMI = 25–30 kg/m2; panel B), and who were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2; panel C). Panel D: the impact of β-blockers on the mean frequency of the onset time of paroxysmal AT/AF grouped in 1-hour intervals over 24-hour period in absolute (mean number of AT/AF events per hour) units was examined in the subgroups of patients with and without these medications (all β-blockers combined, Table 1). Note that the circadian patterns were also examined for each medication listed in Table 1 separately (data not shown); in all these subgroups, the circadian patterns were similar to that shown in this figure. Panel E: the impact of arrhythmia duration on the mean frequency of the AT/AF onset times grouped in 1-hour intervals over 24-hour period in absolute (mean number of AT/AF events per hour) units was examined for VT/VF events lasting < 30 seconds, 30 sec to 1 hour, 1–2 hours, and > 2 hours; n is the number of patients in the corresponding subgroup. See Figure 1 legend for details.

Figure 4.

The impact of demographic and clinical characteristics on the mean frequency of the onset times of paroxysmal AT/AF grouped in 1-hour intervals over 24-hour period in absolute (mean number of AT/AF events per hour) units was examined in the subgroups of: (i) patients with LVEF < 40% versus those with LVEF ≥ 40% (panel A), (ii) males versus females (panel B), (iii) younger (<65 years old) versus older (≥65 years old) patients (panel C), and (iv) patients with versus without coronary artery disease (CAD) (panel D). The number of patients in each subgroup is shown in parentheses. The P-values were calculated using the cosinor analysis and a zero-amplitude test (see Figure 1 legend for details).

A pronounced circadian pattern of the AT/AF initiation (with a nighttime peak and daytime trough level) was observed both in younger (< 65 years old, P<10−5; Fig. 4C) and older patients (≥ 65 years old, P<10−4). This pattern was present in patients with and without coronary artery disease (P = 0.01 and P<10−5, respectively; Fig. 4D), regardless of the NYHA class, the presence or absence of structural heart disease or medications taken, including β-blockers (P<10−4 for all analyses listed above; Fig. 3D). There were no differences between the circadian patterns of AT/AF initiation for the events that occurred in the first 1, 2, 3, 6, 12, or 24 months compared to the entire 36-month period of monitoring (data not shown).

The Impact of Arrhythmia Duration

The circadian pattern of the AT/AF onset times, with a nighttime peak and daytime trough, was preserved and statistically significant in all studied subsets of arrhythmias of various durations (Fig. 3E). However, there was no significant circadian variation in the duration of AT/AF episodes when examined on a patient-by-patient basis.

Circadian Patterns of AT/AF Initiation in Individual Patients

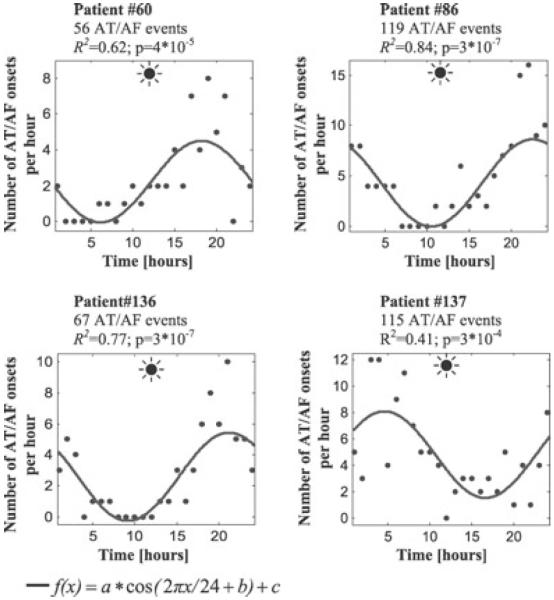

A cosinor analysis of individual patients' data performed in those with ≥ 6 arrhythmic events confirmed that the proportion of patients with a significant (P < 0.05) 24-hour variation of AT/AF onsets increased as a function of individual's AT/AF burden. Indeed, a circadian pattern of arrhythmia initiation was observed in 24% of patients with 6–11 episodes (55 patients), 37% of those with 12–50 episodes (49 patients) and 86% of those with >50 episodes (7 patients). Examples of pronounced 24-hour variation of AT/AF onset frequency in patients with a large number of arrhythmic episodes are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Patterns of initiation of AT/AF events in 4 patients with frequent arrhythmic episodes (>50 events/patient). The line shows the cosine function fitted to the data points (dots) using the nonlinear least-squares (Newton–Gauss) method. The goodness of fit was estimated using R2; the P-values were calculated using a zero-amplitude test (see Figure 1 legend for details). Note that the number of AT/AF events increased in the evening and night time.

As expected, the peak times of AT/AF occurrence exhibited some amount of patient-to-patient variability (Fig. 5). To examine the determinants of such variability, the peak times of AT/AF occurrence have also been examined in the subgroups of patients with different clinical and demographic characteristics. In all examined subgroups, the peak times of arrhythmia occurrence were similar. This suggests that the individual variability in the time of AT/AF occurrence could not be explained by the clinical or demographic characteristics available for this study.

Discussion

In patients with rare arrhythmias (<4 AT/AF episodes over the follow-up period), the events are distributed randomly over a 24-hour period. However, a nocturnal peak emerges in patients with more frequent AT/AF episodes and grows as a function of the total number of arrhythmias. This strong relationship between the nighttime peak of AT/AF initiation and total arrhythmia burden is present in both absolute and patient-normalized units. It is observed in patients of different age groups, genders, irrespective of the level of LVEF, presence of coronary artery disease and pharmacological treatment (including beta-blockers), as well as in the subsets of AT/AF of different duration.

The relationship between a nocturnal pattern of AT/AF and total arrhythmia burden was confirmed by the comparative analysis of the subgroups of patients with <4, 4–9 and 10–50 arrhythmias (Fig. 2A). Because the sample size of all 3 subgroups was similar (69–72 patients), the absence of a circadian pattern of arrhythmia initiation in those with <4 events, in contrast to those with 4–9 and 10–50 arrhythmias, could not be explained by the smaller sample size. In addition, the strong relationship between circadian pattern and the total arrhythmia burden was confirmed by the analysis of individual patient data (Fig. 5).

Previous Studies

To explain the differences in the circadian patterns of AT/AF reported in different populations, Gillis et al. have suggested that the 24-hour distributions are modulated by the disease burden (i.e., the frequency and duration of arrhythmias as well as the presence of structural heart disease).4 Our analysis supports and further extends this notion by showing that the most important determinant of the circadian pattern of AT/AF initiation (among all studied clinical and demographic characteristics) is the total frequency of arrhythmic events.

Interestingly, the nocturnal pattern of AT/AF events has been observed not only in humans, but also in nonprimate mammals. In particular, a similar pattern of AT/AF (with a 12-hour shift due to the nocturnal activity pattern in mice) has been also reported in a genetic mouse model of heart failure and arrhythmias.13 This suggests that the predominance of AT/AF events during the period of rest (inactivity) involves the physiological mechanisms that have been evolutionally “conserved” and independent of species specifics.

Autonomic Nervous System Activity and Circadian Patterns of the AT/AF Initiation

A major role of the ANS in the initiation of AT/AF has long been recognized and supported by a number of experimental and clinical studies.9,19–23 However, despite its long history, the specific contributions of vagal and sympathetic ANS effects to the arrhythmogenesis, as well as the accuracy of estimating those effects in a clinical setting, are still being debated. Coumel has proposed to classify all AT/AF episodes as “vagal” or “sympathetic,” depending on the relative balance between the 2 systems.9 However, a recent large-scale clinical study, which included 5,333 patients with AF from 35 European countries, has demonstrated that a majority of arrhythmic events cannot be classified as purely sympathetic or vagal; only 6% and 15% had vagal and adrenergic trigger patterns, respectively.10 Nevertheless, this large-scale multicenter investigation has confirmed the most important clinical implication of Coumel's theory that β-blockers applied in patients with the vagal type of AT/AF may promote arrhythmogenesis and increase the frequency of arrhythmic events.10

Body Mass Index and Sleep-Disordered Breathing

A link between morbid obesity and obstructive sleep apnea has been well documented, although the exact physiological mechanisms remain debated.24 In our study, however, the nocturnal pattern of AT/AF was similar in all patients, regardless of their BMI. This does not support the notion that obstructive sleep apnea is a primary factor determining a nocturnal pattern of arrhythmias, although we cannot rule out the potential role of central apnea, which is highly prevalent in this population.25 Further research is necessary to delineate the impact of various forms of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) on the nocturnal occurrence of arrhythmias. The central and obstructive SDB have been frequently observed in patients with nocturnal,26 paroxysmal,27 and chronic28,29 atrial fibrillation, although the temporal and causal links between the disordered breathing and arrhythmias remain to be determined.30 SDB is common in patients with low LVEF (<40%),1 who also have chronically elevated sympathetic and limited vagal activity.12

The potential role of short-term surges of parasympathetic activity that may occur during nighttime also requires further investigation.32

Limitations

An absence of data on SDB, oxygen saturation and the level of vagal activity in the studied population did not allow further analysis of these plausible mechanisms of the nocturnal arrhythmia occurrence. Furthermore, the data presented here are from a selected group of patients with implantable devices; therefore, the findings might not be generalizable to a general population of patients with atrial tachyarrhythmias. The number of patients with >50 AT/AF events was relatively small (N = 7), which limited the analysis of circadian patterns in this subgroup. Further research is warranted to examine the reproducibility of our results in various groups of patients. Another important limitation is that device implantation and therapy could potentially interfere and modify the patterns of arrhythmia initiation. To examine the impact of such confounders, we compared all 16,130 AT/AF episodes with the episodes that were preceded by at least 1, 6, and 24 hours of sinus rhythm (Fig. 1). In all 4 datasets, the patterns of AT/AF were similar to each other, showing a pronounced nocturnal peak. The patterns of arrhythmias were also similar in those patients who did not have changes in medication during the follow-up, confirming that the presence of nocturnal peak was independent of specific medication changes (data not shown).

The incidence of AT/AF events in some patients peaked at 8–10 pm and then declined (Fig. 5, patients #60, 86, and 136), which could reflect the effect of medication intake in the evening hours. However, the nocturnal trend was consistently present in patients with and without β-blockers, Ca2+-channel blockers and other antiarrhythmic medications.

It is likely that some patients in our study had abnormal autonomic nervous system activity, which is typical for patients with ICD. Because the heart rate variability and other autonomic markers were not available to us, further research is needed to examine the relationship between autonomic activity and patterns of AT/AF.

Finally, the detection and classification of AT/AF events by the Jewel 7250 AF ICD device in previous studies was reasonably high (approximately, 90%).15 However, as previously acknowledged,15 some events classified by the device as AT may have been an AF, if a thorough electro-physiological evaluation could be conducted.15,33 Based on previous reports, we estimate that the number of such misclassified events is small (within 10%).15

Conclusion

A strong nocturnal peak of AT/AF initiation emerges as a function of total arrhythmia burden. Patients with more frequent arrhythmias are more likely to develop AT/AF at night, which suggests that nighttime physiological and/or pathophysiological events might be responsible for arrhythmia triggering. Therefore, evaluation of nighttime physiology, with particular attention to respiratory function, occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing and apnea is warranted in these patients. In addition, the analysis of autonomic nervous system activity, its potential instabilities and short-term surges of vagal activity, which may occur during the night, might be useful in this patient population. Identifying and mitigating these patient-specific promoters of arrhythmias could facilitate arrhythmia management, reduce the number of arrhythmic events and improve the quality of life in this group.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Grant R44HL077116 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to V. Shusterman.

Footnotes

V. Shusterman owns patents relevant to this topic. E. Warman is an employee of Medtronic, Inc. Other authors: No disclosures.

References

- 1.Scheinman MM, Morady F. Nonpharmacological approaches to atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;103:2120–2125. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.16.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalbfleisch J, Tyler J, Weiss R. A supraventricular tachycardia terminated with ventricular pacing; what is the tachycardia mechanism? Heart Rhythm Journal. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.002. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viskin S, Golovner M, Malov N, Fish R, Alroy I, Vila Y, Laniado S, Kaplinsky E, Roth A. Circadian variation of symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Data from almost 10 000 episodes. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:1429–1434. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillis AM, Connolly SJ, Dubuc M, Yee R, Lacomb P, Philippon F, Kerr CR, Kimber S, Gardner MJ, Tang ASL, Molin F, Newman D, Abdollah H. Circadian variation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:794–798. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamashita T, Murakawa Y, Sezaki K, Inoue M, Hayami N, Shuzui Y, Omata M. Circadian variation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1997;96:1537–1541. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita T, Murakawa Y, Hayami N, Sezaki K, Inoue M, Fukui E, Omata M. Relation between aging and circadian variation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1364–1367. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupari M, Koskinen P, Leinonen H. Double-peaking circadian variation in the occurrence of sustained supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Am Heart J. 1990;120:1364–1369. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90249-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clair WK, Wilkinson WE, McCarthy EA, Page RL, Pritchett EL. Spontaneous occurrence of symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in untreated patients. Circulation. 1993;87:1114–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.4.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coumel P. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: A disorder of autonomic tone? Eur Heart J. 1994;15 A:9–16. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/15.suppl_a.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vos CB, Nieuwlaat R, Crijns HJGM, Camm AJ, LeHeuzey JY, Kirchhof CJ, Capucci A, Breithardt G, Vardas PE, Pisters R, Tieleman RG. Autonomic trigger patterns and anti-arrhythmic treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: Data from the Euro Heart Survey. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:632–639. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lampert R, Rosenfeld L, Batsford W, Lee F, McPherson C. Circadian variation of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary artery disease and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation. 1994;90:241–247. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shusterman V, Aysin B, Gottipaty V, Weiss R, Brode S, Schwartzman D, Anderson KP. ESVEM Investigators: Autonomic nervous system activity and the spontaneous initiation of ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1891–1899. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shusterman V, McTiernan CF, Mehdi H, Troy WC, London B. Circadian pattern to arrhythmias in a genetic mouse model of heart failure. Compu Cardiol. 2009;36:341–344. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman PA, Dijkman B, Warman EN, Xia HA, Mehra R, Stanton MS, Hammill SC. Atrial therapies reduce atrial arrhythmia burden in defibrillator patients. Circulation. 2001;104:1023–1028. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.095039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swerdlow CD, Schls W, Dijkman B, Jung W, Sheth NV, Olson WH, Gunderson BD. Detection of atrial fibrillation and flutter by a dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circulation. 2000;101:878–885. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adler SW, Wolpert C, Warman EN, Musley SK, Koehler JL, Euler DE. Efficacy of pacing therapies for treating atrial tachyarrhythmias in patients with ventricular arrhythmias receiving a dual-chamber implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Circulation. 2001;104:887–892. doi: 10.1161/hc3301.094739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darbar D, Warman EN, Hammill SC, Friedman PA. Recurrence of atrial tachyarrhythmias in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients. PACE. 2005;28:1047–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson W, Tong YL, Lee JK, Halberg F. Methods for cosinorrhythmometry. Chronobiologia. 1979;6:305–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bettoni M, Zimmermann M. Autonomic tone variations before the onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;105:2753–2759. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018443.44005.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomita T, Takei M, Saikawa Y, Hanaoka T, Uchikawa S, Tsutsui H, Aruga M, Miyashita T, Yazaki Y, Imamura H, Kinoshita O, Owa M, Kubo K. Role of autonomic tone in the initiation and termination of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients without structural heart disease. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:559–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmermann M, Kalusche D. Fluctuation in autonomic tone is a major determinant of sustained atrial arrhythmias in patients with focal ectopy originating from the pulmonary veins. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:285–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fioranelli M, Piccoli M, Mileto GM, Sgreccia F, Azzolini P, Risa MP, Francardelli RL, Venturini E, Puglisi A. Analysis of heart rate variability five minutes before the onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. PACE. 1999;22:743–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Berg MP, Hassink RJ, Baljé-Volkers C, Crijns HJGM. Role of the autonomic nervous system in vagal atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2003;89:333–334. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marien H, Rodenstein D. Morbid obesity and sleep apnea. Is weight loss the answer? J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:339–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Köhnlein T, Welte T, Tan LB, Elliott MW. Central sleep apnoea syndrome in patients with chronic heart disease: A critical review of the current literature. Thorax. 2002;57:547–554. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.6.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehra R, Stone KL, Varosy PD, Hoffman AR, Marcus GM, Blackwell T, Ibrahim OA, Salem R, Redline S. Nocturnal arrhythmias across a spectrum of obstructive and central sleep-disordered breathing in older men: Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men (MrOS Sleep) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1147–1155. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevenson IH, Teichtahl H, Cunnington D, Ciavarella S, Gordon I, Kalman JM. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation patients with normal left ventricular function. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1662–1669. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gami AS, Pressman G, Caples SM, Kanagala R, Gard JJ, Davison DE, Malouf JF, Ammash NM, Friedman PA, Somers VK. Association of atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2004;110:364–367. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136587.68725.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braga B, Poyares D, Cintra F, Guilleminault C, Cirenza C, Horbach S, Macedo D, Silva R, Tufik S, De Paola AA. Sleep-disordered breathing and chronic atrial fibrillation. Sleep Med. 2009;10:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gami AS, Friedman PA, Chung MK, Caples SM, Somers VK. Therapy insight: Interactions between atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine. 2005;2:145–149. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald M, Fang J, Pittman SD, White DP, Malhotra A. The current prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in congestive heart failure patients treated with beta-blockers. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:38–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verrier RL, Josephson ME. Impact of sleep on arrhythmogenesis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:450–459. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.867028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells JL, Karp R, Kouchoukos N, Maclean W, James T, Waldo A. Characterization of atrial fibrillation in man: Studies following open heart surgery. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1978;1:426–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1978.tb03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]