Abstract

Relational cultural theory posits that resilience and psychological growth are rooted in relational connections and are facilitated through growth-fostering relationships. Framed within this theory, the current study examined the associations between growth-fostering relationships (i.e., relationships characterized by authenticity and mutuality) with a close friend and psychological distress among sexual minorities. More specifically, we tested the moderating effects of individuals’ internalized homophobia and their friend’s sexual orientation on the associations between growth-fostering relationship with their close friend and level of psychological distress. A sample of sexual minorities (N = 661) were recruited online and completed a questionnaire. The 3-way interaction between (a) growth-fostering relationship with a close friend, (b) the close friend’s sexual orientation, and (c) internalized homophobia was significant in predicting psychological distress. Among participants with low levels of internalized homophobia, a stronger growth-fostering relationship with a close heterosexual or LGBT friend was associated with less psychological distress. Among participants with high levels of internalized homophobia, a stronger growth-fostering relationship with a close LGBT friend was associated with less psychological distress but not with a heterosexual friend. Our results demonstrate that growth-fostering relationships may be associated with less psychological distress but under specific conditions. These findings illuminate a potential mechanism for sexual minorities’ resilience and provide support for relational cultural theory. Understanding resilience factors among sexual minorities is critical for culturally sensitive and affirmative clinical practice and future research.

Keywords: resilience, growth-fostering relationships, internalized homophobia, psychological distress, friends, relational cultural theory, sexual minorities

The Conditions under which Growth-Fostering Relationships Promote Resilience and Alleviate Psychological Distress among Sexual Minorities: Applications of Relational Cultural Theory

For over two decades, studies have documented sexual orientation disparities in mental health (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2011). Sexual minorities are at greater risk for psychological distress and psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety than heterosexuals (IOM, 2011; King et al., 2008), with meta-analyses further underscoring these disparities (e.g., King et al., 2008). Although these disparities are explained by stressors associated with their stigmatized sexual identity and oppression (Meyer, 2003), more research is needed to examine processes that alleviate psychological distress (i.e., promote resilience) among sexual minorities (IOM, 2011).

Resilience can be defined in several ways (Masten, 2007); we utilize relational cultural theory’s position on resilience and apply it to sexual minorities (Miller & Stiver, 1997). Relational cultural theory assumes that relationships are the major contributor to individuals’ ability to be resilient in the face of individually- or culturally-based hardships (Hartling, 2008). In contrast to resilience being a within-person characteristic (e.g., hardiness), it is conceptualized as relational, in which quality relationships are the root of resilience (Hartling, 2008). Given that sexual minorities experience stigma-related stressors varying in individual to structural and cultural forms (e.g., discrimination, heterosexism; Meyer, 2003), we consider resilience as relational factors that have positive effects on health outcomes, such as relational processes that alleviate psychological distress. In fact, much research exists in the sexual minority literature indicating that social supports promote health and alleviate psychological stress (Kwon, 2013).

Relational cultural theory posits that resilience and psychological growth are rooted in relational connections and are developed and facilitated through growth-fostering relationships (Miller & Stiver, 1997). Growth-fostering relationships are high-quality interpersonal connections that are characterized by empathy, mutuality, and empowerment (Jordan, 2009; Miller & Stiver, 1997). Consistent with the theory, growth-fostering relationships with close friends are positively associated with self-esteem and negatively associated with psychological distress, loneliness, depression, and stress among predominately heterosexual college student samples (Frey, Beesley, & Miller, 2006; Frey, Tobin, & Beesley, 2004; Liang et al., 2002). However, there are no studies to date that examine the associations between growth-fostering relationships and psychological distress among sexual minorities and the conditions under which they may alleviate psychological distress.

According to relational cultural theory, individuals internalize experiences of connection and disconnection and develop “relational images” (Jordan, 2009). Relational images can be defined as perceptions of oneself in relationships and his/her expectations from relating with others (Jordan, 2009). People utilize multiple relational images (e.g., relational schemas) to guide their behaviors and interactions with others. Self-disparaging relational images often develop as a result of experiencing direct disconnection from others or from being exposed to or internalizing cultural forms of disconnection (i.e., societal stigma that leaves individuals feeling disconnected from one’s society; Jordan, 2009). According to relational cultural theory, both individual forms of relational disconnection (e.g., rejection, victimization, or discrimination based on sexual identity) and cultural forms of relational disconnection (e.g., living in a stigmatizing society or experiencing systemic oppression) might lead sexual minorities to internalize these experiences and develop self-disparaging relational images specific to their sexual identity, such as internalized homophobia.

As one form of proximal minority stress (Meyer, 2003), internalized homophobia is the internalization of sexual stigma (i.e., negative stereotypes about sexual minorities) into one’s sense of self, also described as internalized heterosexism or self-stigma (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 2009; Szymanski, Kashubeck-West, & Meyer, 2008; Weinberg, 1972). Much research has documented that internalized homophobia is related to poorer health (e.g., depression, anxiety; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Szymanski et al. 2008). In addition to its stressful and negative effects on mental and physical health, internalized homophobia affects how sexual minorities view themselves and relate with others. According to relational cultural theory, self-disparaging relational images (i.e., internalized homophobia) can influence how growth-fostering relationships may impact health (Jordan, 2009). In fact, internalized homophobia is associated with lower social supports and social isolation, which in turn have negative health effects (Puckett, Woodward, Mereish, Pantalone, 2014; Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008). As such, from a relational cultural theory’s perspective, internalized homophobia is conceptualized as a relational and psychological mechanism that influences how individuals relate with others.

Varying levels of internalized homophobia might have implications for understanding the particular conditions under which growth-fostering relationships may be associated with psychological distress. Sexual minorities with high internalized homophobia might be less likely to be open and authentic in otherwise strong growth-fostering relationships, which would nullify the resilience-promoting associations of these relationships (Jordan, 2009). In fact, internalized homophobia is related to less sexual orientation disclosure (Szymanski et al., 2008) and more attempts to pass as heterosexual (Szymanski, Chung, & Balsam, 2001). As such, we examined how self-disparaging relational images specific to sexual orientation (i.e., internalized homophobia) moderate the associations between growth-fostering relationships and psychological distress.

Relational cultural theory emphasizes power dynamics in relationships and posits that individuals may act upon their relational images based on characteristics of the other individual in the interaction (Jordan, 2009). Thus, a sexual minority individual’s internalized homophobia relational image may be enacted differently based on certain factors of the person he/she is interacting (e.g., power dynamics). For this study, we posit that the moderating effect of internalized homophobia on the association between growth-fostering relationships with a close friend and psychological distress might vary based on the characteristics of the close friend, specifically the friend’s sexual orientation. Sexual minorities with high internalized homophobia might have close relationships with heterosexual friends who hold homophobic beliefs and power in the relationship, which could further reinforce their internalized stigma and counter the effects of growth-fostering relationships on psychological distress. Additionally, self-disparaging relational images can lead sexual minorities to expect harmful disconnections in interactions with others (Jordan, 2009), and as such they might be more attuned to their heterosexual friend’s power and might be less open about their sexual orientation with heterosexual friends. In contrast, among sexual minorities with high internalized homophobia, growth-fostering relationships with a close sexual minority friend might still be associated with less psychological distress, because of shared power dynamics and because sexual minority friends might counter or challenge internalized homophobia beliefs. Therefore, it is important to take into account the friend’s sexual orientation.

Purpose of Proposed Study

Utilizing relational cultural theory, we considered growth-fostering relationships with close friends in association with less psychological distress. There is a dearth of literature examining the associations between growth-fostering relationships and psychological distress among sexual minorities and how self-disparaging relational images (i.e., internalized homophobia) might moderate this association. Additionally, the limited literature on social supports has rarely examined the sexual orientation of the provider of social support to sexual minorities. To address these limitations, we hypothesized that growth-fostering relationships would be associated with less psychological distress (i.e., promote resilience) and that this relationship would be dependent on sexual minorities’ levels of internalized homophobia and the sexual orientation of their friend. Specifically, we hypothesized that growth-fostering relationships with close friends would be associated with less psychological distress for sexual minorities with low levels of internalized homophobia because these individuals might be more likely to be authentic and engaged in their relationships, regardless of the friend’s sexual orientation. However, for sexual minorities with high levels of internalized homophobia, we hypothesized that growth-fostering relationships with close friends would be associated with less psychological distress when the friend was a sexual minority but not when the friend was heterosexual.

Method

Participants

Participants were selected for the present study and were part of a larger study on the mental and physical health outcomes of distal and proximal minority stressors among sexual minorities (author citation). Participants were 661 adults ages 18 to 76 years (M = 42.76, SD = 14.80). All male, female, and transgender participants in this sample identified as a sexual minority. Detailed participant demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

| Total Sample (N = 661) | |

|---|---|

| % (n) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 57.3 (379) |

| Female | 41.1 (272) |

| Transgender | 1.5 (10) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Lesbian | 22.4 (148) |

| Gay | 50.1 (331) |

| Bisexual | 27.5 (182) |

| Race | |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 3.8 (25) |

| Black or African American | 7.0 (46) |

| Biracial or Multiracial | 3.6 (24) |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 5.9 (39) |

| Native American | 1.5 (10) |

| White | 76.1 (503) |

| Other | 1.7 (11) |

| Education | |

| Some high school | 2.0 (13) |

| High school degree or equivalent (GED) | 27.1 (178) |

| Associates degree | 15.4 (101) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 30.3 (199) |

| Master’s degree or higher | 25.2 (165) |

| Income | |

| ≤ $9,999 | 13.0 (85) |

| $10,000 – $19,999 | 15.2 (99) |

| $20,000 – $29,999 | 12.7 (83) |

| $30,000 – $49,999 | 19.6 (128) |

| ≥ $50,000 | 39.5 (258) |

| Geographical Region | |

| Northeastern U.S. | 30.9 (203) |

| Midwestern U.S. | 18.8 (124) |

| Northwestern U.S. | 4.7 (31) |

| Southern U.S. | 16.1 (106) |

| Southwestern U.S. | 8.8 (58) |

| Western U.S. | 18.5 (122) |

| Other U.S. Territory | 0.2 (1) |

| International/non-U.S. Territory | 2.0 (13) |

Procedures

The sample was a non-probability sample of sexual minorities, recruited by contacting online LGBT online listservs (e.g., social groups, forums) and an online panel of research participants. Internet recruitment of participants has been described as an important resource for reaching sexual minorities (Meyer & Wilson, 2009). All potential participants provided consent, completed an online survey, and received monetary incentives for participating. Inclusion criteria included being 18 years of age or older and identifying as a sexual minority. More detailed information on recruitment procedures are described elsewhere (author citation).

Measures

Growth-fostering relationship with a close friend

Growth-fostering relationship levels (i.e., high quality relationships characterized to be mutually engaging, empowering, and authentic) with a close friend over the past year were measured with the 8-item Peer Relational Health Index (RHI; Liang et al., 2002; 2007). Item response options are on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always). Participants were provided with a definition of a close friend and were informed to rate the items (e.g., “Even when I have difficult things to say, I can be honest and real with my friend”) regarding one of their closest friends (α =.93). Psychometric analyses have been conducted, and high alpha coefficients have been reported (Liang et al., 2002; 2007). Higher scores indicate greater relationship quality with the close friend.

Sexual orientation of close friend

Following the completion of the RHI scale, participants were asked: “Is this friend Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, or Transgender (LGBT)-identified or Heterosexual?” Response options were: LGBT-identified (n = 325; coded as 0), heterosexual (n = 308; coded as 1), or “I don’t know /I’m not sure” (n = 28). Participants who did not know their friend’s sexual orientation were not included in the regression analyses.

Psychological distress

As two components of psychological distress, we combined the depression (7-items; e.g., “I felt down-hearted and blue”) and anxiety (7-items; e.g., “I found it difficult to relax”) subscales of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) to assess psychological distress over the past year. Item response options are on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (Did not apply to me at all) to 4 (Applied to me very much, or most of the time). The scale was previously psychometrically validated with non-clinical participants (Crawford & Henry, 2003) and among sexual minorities (Masini & Barrett, 2007). Higher scores indicate higher levels of distress. Strong reliability was demonstrated (α = .94).

Internalized homophobia

The 5-item Revised Internalized Homophobia Scale (Herek et al., 2009) assessed internalized homophobia over the past year. Item response options are on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly), with items such as “I wish I weren’t lesbian/gay/bisexual” (α = .89). Psychometric properties of this measure have been tested with a sexual minority adults and found adequate alpha reliability coefficients (Herek et al., 2009). Higher scores indicate higher levels of internalized homophobia.

Results

Basic Correlations and Group Differences

Correlations among the variables and their means and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. Although participants in our non-clinical sample endorsed items of the internalized homophobia and psychological distress measures, the mean scores of these scales indicate that on average participants had low levels of internalized homophobia and psychological distress; they had moderate levels of growth-fostering relationships with their reported close friend.

Table 2.

Correlations among and Basic Descriptive of the Variables

| Measure | Internalized Homophobia |

GFR with a Close Friend |

Psychological Distress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internalized Homophobia | ― | ||

| GFR with a Close Friend | −.11** | ― | |

| Psychological Distress | .33** | −.15** | ― |

| Mean | 1.60 | 3.82 | 1.70 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.67 |

| Range | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–4 |

Note. N = 661. GFR with a Close Friend = Growth-fostering relationship with a close friend.

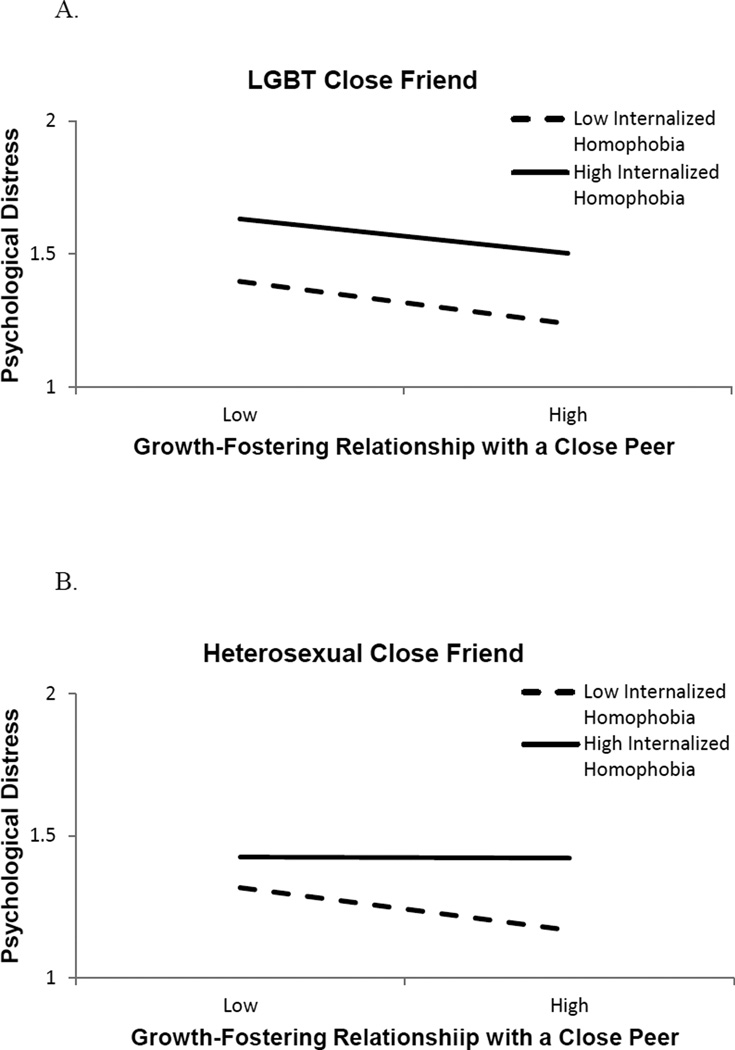

We conducted hierarchical regression analyses to test the moderating effects of internalized homophobia and the sexual orientation of a close friend on the associations between growth-fostering relationships and psychological distress. We followed the commonly used procedures for testing moderation (Aiken & West, 1991). We standardized our variables to reduce the effects of multicolinearity. We accounted for age, gender, education, race, and participants’ sexual orientation (coded as lesbian/gay = 0, bisexual = 1) and entered these variables on Step 1. We entered the main effects on Step 2, the two-way interactions on Step 3, and the three-way interaction of growth-fostering relationships, internalized homophobia, and the friend’s sexual orientation on Step 4. The three-way moderating effect was significant (β =.14, p < .05; Table 3; Figures 1A and 1B).

Table 3.

Regressions Results of Three-Way Interaction in Predicting Psychological Distress

| Independent Variables | B | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 4: Three-Way Interaction | .22*** | ||

| Control Variables | |||

| Age | −.01 | −.14*** | |

| Gender | .09 | .07 | |

| Education | −.06 | −.10** | |

| Race/ethnicity | .01 | .08* | |

| Sexual Orientation (Lesbian/Gay vs. Bisexual) | .10 | .07 | |

| Main Effects | |||

| GFR with a Close Friend | −.17 | −.22*** | |

| Internalized Homophobia | .29 | .37*** | |

| Friend’s Orientation (LGBT vs Heterosexual) | −.12 | −.09* | |

| Two-Way Interactions | |||

| GFR with a Close Friend × Internalized Homophobia | .04 | .04 | |

| GFR with a Close Friend × Friend’s Orientation | .08 | .08 | |

| Internalized Homophobia × Friend’s Orientation | −.09 | −.08 | |

| Three-Way Interaction | |||

| GFR with a Close Friend × Internalized Homophobia × Friend’s SO | .15 | .14* |

Note. GFR with a Close Friend = Growth-fostering relationships with a close friend; Friend’s SO = close friend’s sexual orientation.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 1.

To aid in the interpretation of the three-way moderating effect, we computed simple slope regressions (Aiken & West, 1991). We split participants into four groups based on whether their growth-fostering relationship was either with a heterosexual friend or an LGBT friend and based on their low or high levels of internalized homophobia (categorized based on one half standard deviation below or above the mean). Among participants with low levels of internalized homophobia, growth-fostering relationship with a close heterosexual or LGBT friend were associated with less psychological distress (β = −.31 and −.26, p <.001, respectively; Figures 1A and 1B). Among participants with high levels of internalized homophobia, only growth-fostering relationship with a close LGBT friend were associated with less psychological distress (β = −.31, p <.05).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that growth-fostering relationships are a possible mechanism related to sexual minorities’ resilience. Supporting relational cultural theory, we found that growth-fostering relationships with a close friend were associated with less psychological distress. However, our findings indicate that this process is nuanced by levels of individuals’ internalized homophobia and their friends’ sexual orientation. This is an important contribution because much of the social support literature among sexual minorities has not focused on whom it is provided by, and has focused on the quantity rather than quality of supports. Our results are also important because they provide a relational perspective to sexual minority resilience and one type of minority stress.

Consistent with relational cultural theory (Jordan, 2009), we found that growth-fostering relationships with close heterosexual and LGBT friends were associated with less psychological distress when sexual minorities’ internalized homophobia was low. Given that growth-fostering relationships are characterized by relational elements of empathy, mutuality, and empowerment (Jordan, 2009), these relationships have important resilience and health-promoting effects. These positive associations may have been possible in the low internalized homophobia group because these individuals might have felt comfortable with their sexual orientation and in turn allowed them to derive the full benefits of growth-fostering relationships, whether the friend was heterosexual or LGBT. In fact, sexual minorities with lower internalized homophobia are more likely to accept and disclose their sexual orientation to others (Szymanski et al., 2008). Our results support the general literature documenting positive relations between growth-fostering relationships and health and overall well-being (Frey et al., 2006; Frey et al., 2004) and extend the literature to provide empirical support for growth-fostering relationships among sexual minorities.

Growth-fostering relationships with LGBT friends were consistently related to less psychological distress, regardless of sexual minorities’ relational image with respect to levels of internalized homophobia. Congruent with feminist thinking, relational cultural theory emphasizes the role of power dynamics (Jordan, 2009). It is possible that growth-fostering relationships with LGBT friends had a consistent association because of their “power with” role in these connections compared to having a “power over” role that might more likely to occur in friendships with heterosexual friends. Having shared power might allow for more of growth-fostering relationships’ resilience-promoting benefits. Additionally, LGBT friends more than heterosexual friends might counter or challenge these beliefs and help validate and promote more affirming attitudes toward one’s self.

In contrast to growth-fostering relationships with LGBT friends, growth-fostering relationships with heterosexual friends were not associated with less psychological distress for sexual minorities with high levels of internalized homophobia. Given that self-disparaging relational images can lead sexual minorities to expect harmful disconnections in relational interactions with others (Jordan, 2009), sexual minorities might experience their internalized homophobia in a more stressful way around heterosexual friends and experience or expect more of the relational power dynamics; thus, they might be less open about their sexual orientation. Congruent with this idea, internalized homophobia is related to less sexual orientation disclosure to heterosexual friends (Szymanski et al., 2008). Therefore, sexual minorities with high internalized homophobia might be less likely to be open and authentic with their heterosexual friends, which could have countered the normally anticipated resilience-promoting effects of growth-fostering relationships. Our results also suggest the need for the tenets of relational cultural theory to be adapted to consider the potential conditions in which growth-fostering relationships may or may not be resilience promoting for everyone.

It is important to discuss alternative pathways not examined in this study. It is plausible that growth-fostering relationships might help sexual minorities to disentangle their internalized homophobia by feeling more empowered about their sexual minority identity, and consequently have lower psychological distress (i.e., internalized homophobia might mediate the association between growth-fostering relationships and psychological distress). However, a host of relationship qualities need to exist for this process to occur (e.g., the close friend would need to have affirming sexual orientation beliefs, sexual minorities would need to be out to their close friend, etc.). Given that internalized homophobia is a relational and psychological mechanism that influences how individuals relate to others, future research should investigate the reciprocal ways in which internalized homophobia might impact being authentic in relationships (i.e., development of growth-fostering relationships) and in which growth-fostering relationships might help individuals become more self-affirming of their identity.

We note limitations of the present study and some future directions for research. Our sample was predominately White and highly educated, limiting the generalizability of our results to sexual minorities from diverse racial/ethnic and educational backgrounds. Future research should examine more heterogeneous samples of sexual minorities. Although we accounted for several variables (i.e., age, gender, education, race, sexual orientation) and while these background variables were mostly not significant in our model, future research should examine how our results might apply across these demographic groups (e.g., sexual minorities from different age groups). Because of our study’s cross-sectional design, we cannot assume causal relationships; longitudinal research studies are needed to more rigorously examine our findings.

Another limitation of this study is the lack of information known about the relationship between our participants and their reported close friend (e.g., nature of their friendship; whether participants had disclosed their sexual orientation to their friend; the level of homophobia observed and/or expressed by the friend). Future research should examine these constructs in order to potentially explain some of the findings of our current study. Additionally, our results are limited to growth-fostering relationships with one close friend. Participants may potentially have multiple growth-fostering relationships with friends from diverse sexual orientation backgrounds; thus, research should examine how individuals’ broader social network and its particular sexual orientation composition contribute to individuals’ resilience. Research is also needed to better examine the complexity and the unique resilience-promoting contributions of other types of growth-fostering relationships (e.g., romantic partners). Also, our item assessing the friend’s sexual orientation was limited because it inadvertently included sexual minorities and gender minorities into one category. Future research needs to better delineate how the gender and gender identity of a friend might also factor into our findings.

In framing internalized homophobia from a relational cultural theory perspective, our results accentuate the insidious effects of self-disparaging relational images on the association between growth-fostering relationships and psychological distress. These findings provide support for and underscore the relevance of relational cultural theory. Given its emphasis on relational connections, empowerment, and resilience within a cultural framework, relational cultural theory has many potential contributions to understanding sexual minorities’ health. Future research should utilize relational cultural theory to better understand sexual minorities’ wellbeing and identify relevant theory-driven points of intervention.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded in part by the Malyon-Smith Scholarship Award from the Society for the Psychological Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues of the American Psychological Association, and by the Boston College Lynch School of Education Summer Dissertation Development Grant in support of Ethan Mereish. Manuscript preparation was supported in part by grant number T32DA016184 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health in support of Ethan Mereish.

Contributor Information

Ethan H. Mereish, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Brown University, Box G-S121-4, Providence, RI 02912, Tel: (401) 863-6631, ethan_mereish@brown.edu

V. Paul Poteat, Department of Counseling, Developmental, and Educational Psychology, Campion Hall 307, 140 Commonwealth Ave., Chestnut Hill, MA 02467, Paul.poteat@bc.edu

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Frey LL, Beesley D, Miller M. Relational health, attachment, and psychological distress in college women and men. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Frey LL, Tobin J, Beesley D. Relational predictors of psychological distress in women and men presenting for university counseling center services. Journal of College Counseling. 2004;7:129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hartling LM. Strengthening resilience in a risky world: It's all about relationships. Women & Therapy. 2008;31:51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JV. Relational-cultural therapy. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kashubeck-West S, Szymanski D, Meyer J. Internalized heterosexism: Clinical implications and training considerations. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:15–630. [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai S, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70–78. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Tracy A, Taylor CA, Williams LM, Jordan JV, Miller JB. The relational health indices: A study of women's relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2002;26:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Tracy A, Glenn C, Burns SM, Ting D. The relational health indices: Confirming factor structure for use with men. The Australian Community Psychologist. 2007;19:35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini BE, Barrett HA. Social support as a predictor of psychological and physical well-being and lifestyle in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults aged 50 and over. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2008;20:91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mastin AS. Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:921–930. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Wilson P. Sampling Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB, Stiver IP. The healing connection: How women form relationships in therapy and in life. Boston, M.A.: Beacon Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb M, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Woodward E, Mereish EH, Pantalone DW. Parental rejection following sexual orientation disclosure: Impact on internalized homophobia, social support, and mental health variables. LGBT Health. 2014 doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Kashubeck-West S. Mediators of the relationship between internalized oppressions and lesbian and bisexual women's psychological distress. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:575–594. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski D, Chung B, Balsam K. Correlates of internalized homophobia in lesbians. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2001;34:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Kashubeck-West S, Meyer J. Internalized heterosexism: Measurement, psychosocial correlates, and research directions. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:525–574. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg G. Society and the healthy homosexual. New York: St. Martin’s; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Wong P. Resilience in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2013;17:371–383. doi: 10.1177/1088868313490248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]