Abstract

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection can be reactivated during lymphoma chemotherapy, specifically with rituximab. In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and, in 2010, the American Society of Clinical Oncology made recommendations that anyone who received cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy should be tested for serologic markers of HBV infection. In our study, we wanted to determine the screening rates for HBV infection at our institution and if simply adding a checkbox onto the rituximab order would improve HBV screening. We performed a retrospective chart review of two cohorts of lymphoma patients at Scott & White Health Clinic. Cohort 1 included patients from 1993 to 2008. Cohort 2 included patients who received rituximab after an institutionwide protocol (rituximab order checkbox) was initiated in 2011. A total of 452 patients treated for lymphoma were reviewed. Only 15 of the 404 Cohort 1 patients received HBV screening (3.7%; 95% confidence interval, 2.1%–6.1%). Screening rates were statistically higher if baseline liver laboratory values were elevated (P < 0.0001). HBV was also checked more frequently if patients' liver function tests became elevated while on chemotherapy, 85.7% (12/14). Of the 48 patients in Cohort 2, 33 patients (68.7%) received HBV screening. No patients in either cohort had a positive HBV surface antigen or developed reactivation of HBV during chemotherapy. The addition of a checkbox on the rituximab order form significantly increased our screening for HBV infection in lymphoma patients initiating chemotherapy.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common cause of chronic hepatitis worldwide, carrying a high morbidity and mortality. It is a well-known cause of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. An estimated one-third of the world's population has past or present serological evidence of HBV infection. Approximately 350 million people are known to be carriers of hepatitis B, with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity having the highest prevalence in Southeast Asia and Western Pacific regions (1). A half a million of these carriers die annually from HBV-related liver disease (2). The United States has 1.5 million HBsAg carriers with approximately 300,000 active HBV cases per year. This number is steadily increasing due to immigration from regions with high endemic HBV infection, injection drug use, and high-risk sexual behavior (3–5).

The natural course of HBV infection is determined by the relationship between virus replication and host immune response. The virus persists in the host even after serological recovery from acute HBV. Therefore, this cohort is at risk for reactivation of infection when the immune response is suppressed. Reactivation of HBV has been well documented in patients receiving chemotherapy, immunosuppressive therapy, and cytotoxic agents. Clinical symptoms of HBV reactivation range from isolated acute aminotransferase elevation to severe hepatic failure (1, 6). Perrillo et al noted a 40% HBV reactivation rate among patients receiving chemotherapy who were positive for HBV surface antigen. Those who did reactivate had a 13% risk of liver failure and 16% mortality (7).

Two clinical scenarios contribute to reactivation. The first occurs in patients with chronic HBV infection who are considered to be immunotolerant. In these patients, the diagnosis of HBV reactivation is established after the HBV DNA level becomes detectable in the setting of hepatitis. In the second scenario, reactivation of HBV occurs in patients who had resolved HBV infection. These patients previously developed antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (with or without antibody to HBsAg). In these patients, HBV replication has been shown to persist in the liver and peripheral mononuclear cells for decades (8–10). Multiple reports have described HBV reactivation in patients who are undergoing chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy for a variety of hematologic and solid tumors (11–24). Withdrawal of chemotherapy presents the greatest risk for reactivation, ranging from approximately 20% to 50% among HBsAg-positive carriers (15, 16, 25–27).

Screening and initiating treatment for HBV prior to immunosuppressive treatment is recommended for patients with an increased risk for chronic hepatitis by the American Society of Clinical Oncology in their most recent guidelines from 2010 (28). Highly immunosuppressive treatments include, but are not limited to, hematopoietic cell transplantation and regimens that include rituximab. Despite recommendations from established guidelines, HBV screening prior to chemotherapy is not consistently practiced among physicians. Suboptimal screening and prophylaxis can lead to fatal outcomes in patients who are at risk for reactivation of HBV. This highlights the importance of developing protocols to improve awareness and increase screening rates of HBV reactivation in our institution.

In our study, we evaluated screening for HBV infection in patients undergoing chemotherapy for lymphoma at our institution between 1993 and 2008 (Cohort 1). We then evaluated HBV screening rates starting in May 2011 (Cohort 2), after our institution initiated a protocol for screening prior to starting rituximab therapy for lymphoma.

METHODS

The Cohort 1 data were collected through a retrospective chart review of 404 lymphoma patients at our institution using deidentified demographics and laboratory values. Patient medical records were accessed using medical record numbers for further data retrieval.

The deidentified demographic data, including date of birth, gender, and race, were logged on the individualized data parameter sheet. The cancer type, stage, grade, age at diagnosis, and date of diagnosis were documented using the cancer registries. A review of the electronic medical records was performed to identify the date of completion of chemotherapy as well as the chemotherapeutic agent used. This information was cross-referenced with laboratory data to identify whether patients were screened for hepatitis B surface antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core IgM antibody, or hepatitis B core IgG antibody. The date of screening was documented for patients with available screening data.

Subsequently, results of liver function tests (LFTs)—aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin—prior to, during, and after chemotherapy were documented. Normal ranges as identified by our institution's laboratory were used. Liver flare was defined as more than a twofold increase from a patient's baseline in a LFT, including AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, or total bilirubin.

In 2011, our oncology department created a preprinted order set for rituximab with a checkbox option for HBV testing to serve as a reminder to screen this patient population. Cohort 2 data were collected after this new protocol was put into effect. Patients were selected using our tumor registry and filtered for those receiving chemotherapy regimens that included rituximab.

All variables were summarized using descriptive statistics: mean (standard deviation) and median (minimum-maximum) for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. The HBV screening rate and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for the entire cohort. HBV screening rates between normal and abnormal LFT cohorts were compared using a chi-square test. The association between HBV testing and the presence or absence of abnormal LFT was assessed using Fisher's exact test. A P value <0.05 indicated statistical significance. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes patient demographic characteristics and lymphoma stage for Cohort 1. As shown in Table 2, 33.4% (135/404) of these patients were on a chemotherapy regimen that included rituximab. Only 15 out of 404 Cohort 1 patients received HBV testing. This translated to a screening rate of 3.7%, with a 95% CI of 2.1% to 6.1%. Among the 404 patients, 204 had normal baseline LFTs and 200 had abnormal LFTs. No patient in the normal LFT subgroup received the HBV screening, whereas 15/200 (7.5%; 95% CI, 4.3%–12.1%) patients in the abnormal LFT subgroup received the HBV testing (Table 3). The testing rates between patients with normal LFTs and abnormal LFTs were significantly different (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in Cohort 1 lymphoma patients (N = 404)

| Testing for hepatitis B |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Variable | N (%)* | Yes (N = 15) | No (N =389) |

| Age | Mean ± SD (years) | 59 ± 20 | 54 ± 15 | 59 ± 20 |

| Sex | Male | 216 (54%) | 11 (73%) | 205 (52%) |

| Female | 188 (47%) | 4 (27%) | 184 (47%) | |

| Race | White | 369 (91%) | 11 (73%) | 358 (92%) |

| Black | 28 (7%) | 4 (27%) | 24 (6%) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Other | 6 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Stage | 1 | 21 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (5%) |

| 2 | 45 (11%) | 1 (7%) | 44 (11%) | |

| 3 | 48 (12%) | 1 (7%) | 47 (12%) | |

| 4 | 71 (18%) | 4 (27%) | 67 (17%) | |

| Unknown | 219 (54%) | 9 (60%) | 210 (54%) | |

Results indicate frequency (column percentage) unless otherwise specified.

Table 2.

Presence of liver flare by lymphoma chemotherapy type (n = 404)*

| Chemotherapy | Flare | No flare | Unknown* |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-CHOP† | 32 (74.4%) | 11 (25.6%) | 55 |

| CHOP | 26 (81.3%) | 6 (18.9%) | 83 |

| ABVD | 21 (84.0%) | 4 (16.0%) | 30 |

| R-COP/R-CVP† | 11 (68.9%) | 5 (31.3%) | 14 |

| COP/CVP | 7 (87.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 20 |

| HYPER-CVAD | 5 (83.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 10 |

| RICE† | 4 (80.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 2 |

| MOPP | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 4 |

| BEACOPP | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 0 |

| Cytarabine | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 |

| STANDFORD V | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| Other | 36 (75.0%) | 12 (25.0%) | 75 |

| Unknown | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 6 |

| Total | 145 | 43 | 302 |

Results indicate frequency (row percentage, excluding unknowns). Flare is defined as more than a twofold increase in either aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, or total bilirubin levels from the patient's baseline. For the last column, it was unknown whether the patients had a flare or not, since baseline liver function tests were not available.

Regimens containing rituximab.

Table 3.

Rate of hepatitis screening before and after the intervention*

| N | Number screened | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1: Preintervention | 404 | 15 | 4% |

| Normal liver function tests | 204 | 0 | 0 |

| Abnormal liver function tests | 200 | 15 | 7.5% |

| Cohort 2: Postintervention | 48 | 33 | 69% |

No patient in either cohort had a positive hepatitis B surface antigen or developed reactivation during chemotherapy.

Of the 14 patients in Cohort 1 who were tested for HBV and had available screening LFT measurements, 85.7% (12/14) were noted to have a liver flare at some point during chemotherapy. Of the 139 patients who were not tested for HBV, 75.5% (105/139) showed signs of a liver flare. Based on Fisher's exact test, there was no significant association (P = 0.52) between HBV testing and presence/absence of liver flare.

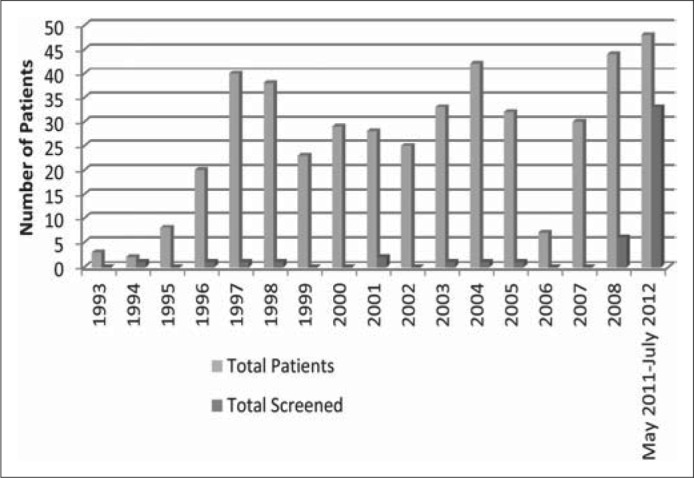

HBV testing rates in lymphoma patients were collated by year from 1993 to 2008 (Figure 1). In general, there was no significant trend of improved screening rates with time, proving that HBV screening was grossly underused. It is suspected that patients may have been initially screened due to abnormal LFTs and not to prevent reactivation HBV.

Figure 1.

Hepatitis B screening rates by year.

Following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's 2008 and the American Society of Clinical Oncology's 2010 guidelines, our facility implemented an HBV screening protocol in 2011 for patients with lymphoma prior to the onset of rituximab therapy. A total of 48 patients met this criterion during our follow-up period of May 2011 through July 2012. Of these patients in Cohort 2, 33 (68.7%) received HVB screening prior to initiating rituximab therapy (Figure 1). Our institution's intervention significantly increased HVB screening rates for patients who would be treated with rituximab (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that despite recognized HBV reactivation in immunosuppressed patients, screening rates before initiating chemotherapy prior to institution protocol (1993–2008) were very low (3.7%). Cohort 1 consisted of lymphoma patients who received any chemotherapy. Of the 404 patients with lymphoma in Cohort 1, only 15 were screened for hepatitis before chemotherapy was initiated. Of those, all 15 had baseline abnormal aminotransaminases, which supports the hypothesis that HBV was likely checked for diagnostic rather than screening purposes. Of the 135 patients who received a chemotherapy regimen that included rituximab (R-CHOP, R-COP/R-CVP, and RICE), 47 had abnormal LFTs at some point throughout treatment (Table 2). The screened patients tended to have more advanced lymphoma as well as baseline abnormal LFTs before chemotherapy induction. After incorporating a screening protocol in 2011 for all lymphoma patients receiving rituximab therapy, our screening rates improved significantly. From May 2011 to July 2012, 48 patients were identified with lymphoma with plans for rituximab chemotherapy (Cohort 2). Of these 48 patients, 33 (68.7%) received HBV testing.

None of the patients in our pre- or postintervention cohorts had a history of HBV infection prior to being diagnosed with cancer or were positive when tested with screening hepatitis panels. In our preintervention cohort, not all the patients with elevated aminotransaminases had screening hepatitis panels performed. The elevation in LFTs in our patient population, therefore, cannot be explained by reactivation hepatitis. In many cases, patients had radiologic evidence of liver metastases, and this is the most likely explanation for their laboratory abnormalities. Also, we cannot rule out the possibility of chemotherapy itself causing elevated transaminases. There were also patients whose clinical course deteriorated and they ultimately ended up on hospice care; it is likely that the cause of LFT abnormalities in this population was multifactorial.

The particular strength of our study is a large sample size collected over several years. We initially searched over 2100 electronic medical records. Ultimately, 452 of those had complete information available for our study. We were able to identify lymphoma patients specifically from the tumor registry.

Our study has some limitations. It is a retrospective study, and clinical details were sometimes difficult to procure. A prospective study would more accurately ascertain specific causes for LFT elevation. Explanations for laboratory abnormalities were often drawn from educated inferences during review of progress notes. Furthermore, a prospective study would allow for selection and inclusion of patients with a history of treated or cleared HBV.

It is also worth noting that our particular patient population had a very low prevalence of HBV. Our liver clinics have over 10 times the number of hepatitis C patients compared to HBV. We have a very low number of Asian and Pacific Islander patients in our population. Previous screening studies at our institution for viral hepatitis found no new cases of HBV (29).

We acknowledge that there is limited literature regarding HBV reactivation with chemotherapy besides lymphoma treatment with rituximab. Furthermore, the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends clinical judgment when screening for HBV infection in patients who are undergoing chemotherapy or chemoradiation. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends that patients at high risk of HBV should undergo testing for HBsAg and anti-HBc before any chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that patients who have risk factors for HBV infection be tested for exposure to HBV prior to initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Serologic testing should include assessment of HBsAg, anti-HBs, and anti-HBc; further testing should include HBeAg, anti-HBe, and an HBV DNA level if the patient is HBsAg positive. As noted in the literature, the strongest evidence is in patients treated for lymphoma, especially those receiving rituximab, and in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, studies are limited on other cancer types, and there is not enough evidence to withhold screening on high-risk patients.

Our study concluded that our institution did not previously consistently screen for HBV infection in lymphoma patients; however, after an HBV screening protocol was implemented in 2011, our screening rates improved significantly. No patients in our pre- or postintervention populations had a positive HBsAg or developed reactivation during chemotherapy. However, the potential risk of HBV reactivation is significant enough that screening and prophylaxis should at least be considered in all patients at high risk for HBV undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy. For this reason, we intend to continue efforts to educate our clinicians to improve awareness of potential HBV reactivation and increase our screening rates even more.

References

- 1.Seetharam A, Perrillo R, Gish R. Immunosuppression in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2014;13:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s11901-014-0238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maynard JE. Hepatitis B: global importance and need for control. Vaccine. 1990;8(Suppl):S18–S20. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niitsu N, Hagiwara Y, Tanae K, Kohri M, Takahashi N. Prospective analysis of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma after rituximab combination chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(34):5097–5100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmore TN, Shah NL, Loomba R, Borg BB, Lopatin U, Feld JJ, Khokhar F, Lutchman G, Kleiner DE, Young NS, Childs R, Barrett AJ, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH, Heller T. Reactivation of hepatitis B with reappearance of hepatitis B surface antigen after chemotherapy and immunosuppression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1130–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson PA, Tam CS, Thursky K, Seymour JF. Hepatitis-B reactivation and rituximab-containing chemotherapy: an increasingly complex clinical challenge. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(9):1592–1595. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.509456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lok AS, Ward JW, Perrillo RP, McMahon BJ, Liang TJ. Reactivation of hepatitis B during immunosuppressive therapy: potentially fatal yet preventable. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(10):743–745. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrillo RP, Martin P, Lok AS. Preventing hepatitis B reactivation due to immunosuppressive drug treatments. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1617–1618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yağci M, Ozkurt ZN, Yeğin ZA, Aki Z, Sucak GT, Haznedar R. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in HBV-DNA negative and positive patients with hematological malignancies. Hematology. 2010;15(4):240–244. doi: 10.1179/102453309X12583347114059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Power JP, El Chaar M, Temple J, Thomas M, Spillane D, Candotti D, Allain J. HBV reactivation after fludarabine chemotherapy identified on investigation of suspected transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus. J Hepatol. 2010;53(4):780–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsutsumi Y, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M, Masauzi N. Prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation under rituximab therapy. Immunotherapy. 2009;1(6):1053–1061. doi: 10.2217/imt.09.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhédin N, Douvin C, Kuentz M, Saint Marc MF, Reman O, Rieux C, Bernaudin F, Norol F, Cordonnier C, Bobin D, Metreau JM, Vernant JP. Reverse seroconversion of hepatitis B after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective study of 37 patients with pretransplant anti-HBs and anti-HBc. Transplantation. 1998;66(5):616–619. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199809150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng JC, Liu MC, Tsai SY, Fang WT, Jer-Min Jian J, Sung JL. Unexpectedly frequent hepatitis B reactivation by chemoradiation in postgastrectomy patients. Cancer. 2004;101(9):2126–2133. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang JW, Choi JY, Bae SH, Kim CW, Yoon SK, Cho SH, Yang JM, Ahn BM, Lee CD, Lee YS, Chung KW, Sun HS. Transarterial chemo-lipiodolization can reactivate hepatitis B virus replication in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2004;41(3):427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau GK, Leung YH, Fong DY, Au WY, Kwong YL, Lie A, Hou JL, Wen YM, Nanj A, Liang R. High hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA viral load as the most important risk factor for HBV reactivation in patients positive for HBV surface antigen undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2002;99(7):2324–2330. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, Wong KL, Chan TK, Todd D. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. Report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(1):182–188. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90599-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markovic S, Drozina G, Vovk M, Fidler-Jenko M. Reactivation of hepatitis B but not hepatitis C in patients with malignant lymphoma and immunosuppressive therapy. A prospective study in 305 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46(29):2925–2930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura Y, Motokura T, Fujita A, Yamashita T, Ogata El. Severe hepatitis related to chemotherapy in hepatitis B virus carriers with hematologic malignancies. Survey in Japan, 1987–1991. Cancer. 1996;78(10):2210–2215. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961115)78:10<2210::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu D, Nomura K, Matsumoto Y, Ueda K, Yamaguchi K, Minami M, Itoh Y, Horiike S, Morita M, Taniwaki M, Okanoue T. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in a patient undergoing steroid-free chemotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(15):2301–2302. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i15.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soong YL, Lee KM, Lui HF, Chow WC, Tao M, Li Er Loong S. Hepatitis B reactivation in a patient receiving radiolabeled rituximab. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(1):61–62. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0948-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsutsumi Y, Kawamura T, Saitoh S, Yamada M, Obara S, Miura T, Kanamori H, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M, Masauzi N. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in a case of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and rituximab: necessity of prophylaxis for hepatitis B virus reactivation in rituximab therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(3):627–629. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000151923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, Hui P, Leung NW, Zee B, Johnson PJ. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62(3):299–307. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200011)62:3<299::aid-jmv1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeo W, Lam KC, Zee B, Chan PS, Mo FK, Ho WM, Wong WL, Leung TW, Chan AT, Ma B, Mok TS, Johnson PJ. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing systemic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1661–1666. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zell JA, Yoon EJ, Ignatius Ou SH, Hoefs JC, Chang JC. Precore mutant hepatitis B reactivation after treatment with CHOP-rituximab. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16(1):83–85. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200501000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim MK, Ahn JH, Kim SB, Im YS, Lee SI, Ahn SH, Son BH, Gong G, Kim HH, Kim WK. Hepatitis B reactivation during adjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: a single institution's experience. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22(4):237–243. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2007.22.4.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoofnagle JH, Dusheiko GM, Schafer DF, Jones EA, Micetich KC, Young RC, Costa J. Reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection by cancer chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(4):447–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-4-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lau JY, Lai CL, Lin HJ, Lok AS, Liang RH, Wu PC, Chan TK, Todd D. Fatal reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection following withdrawal of chemotherapy in lymphoma patients. Q J Med. 1989;73(270):911–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thung SN, Gerber MA, Klion F, Gilbert H. Massive hepatic necrosis after chemotherapy withdrawal in a hepatitis B virus carrier. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(7):1313–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Artz AS, Somerfield MR, Feld JJ, Giusti AF, Kramer BS, Sabichi AL, Zon RT, Wong SL. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: chronic hepatitis B virus infection screening in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy for treatment of malignant diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3199–3202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sears DM, Cohen DC, Ackerman K, Ma JE, Song J. Birth cohort screening for chronic hepatitis during colonoscopy appointments. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(6):981–989. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]