Abstract

Purpose

Poor mental health is associated with teen dating violence (TDV), but whether there are specific types of psychiatric disorders that could be targeted with intervention to reduce TDV remains unknown.

Methods

Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess the associations of psychiatric disorders that emerged prior to dating initiation with subsequent physical dating violence in a nationally representative sample from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, adjusting statistically for adverse childhood experiences.

Results

In adjusted models, internalizing disorders (AOR 1.14, 95% CI 1.04, 1.25; no sex differences noted) and externalizing disorders (males: AOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.10, 1.49; females: AOR 1.85, 95% CI 1.55, 2.21) were associated with subsequent involvement in any physical dating violence victimization or perpetration before the age of 21. Those at greatest risk included girls with ADHD and substance use, in particular.

Conclusions

The range of psychiatric disorders associated with of TDV is broader than has generally been recognized for both boys and girls. Clinical and public health prevention programs should incorporate strategies for addressing multiple pathways through which poor mental health may put adolescents at risk for TDV.

Keywords: Dating violence, adolescents, mental health, adverse childhood experiences

Introduction

Teen dating violence (TDV) is a significant public health concern as an estimated 20-33% [1-3] of adolescents experience physical or sexual abuse at the hands of a romantic partner, while 15-40% of adolescents report perpetrating such abusive behavior [4, 5]. Numerous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have found that exposure to TDV is associated with poor mental health outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidality [1, 4, 6-10]. Fewer studies have assessed the opposite possibility, specifically whether mental health disorders in childhood and adolescence, prior to when adolescents begin dating, are associated with subsequent violence in romantic or dating relationships. This small body of literature suggests that early onset psychiatric disorders may be often overlooked, potentially modifiable risk factors for subsequent TDV victimization and perpetration [11, 12], though these studies do not take into account the degree to which other forms of childhood adversity, including physical and sexual abuse, confound the relationship between poor mental health and TDV in adolescence and young adulthood.

Several cross-sectional studies have indicated that substance use among adolescents is a particularly important correlate of TDV, though because of their study design and lifetime assessment of key variables, these studies cannot assess the relative timing of substance use and TDV victimization or perpetration [1, 13]. One recent longitudinal study found that any lifetime substance use at baseline predicted TDV one year later [14], though this study does not account for important confounders, including adverse childhood experiences (ACE) such as child maltreatment [15, 16]. Research has hypothesized that ACE may result in emotional dysregulation in adolescence, poor relationship skills, and subsequent TDV or, alternatively, be an important marker of social vulnerability placing adolescents at greater risk for substance use and TDV [17]. Accounting for ACE while assessing the relationship between substance use, other psychiatric disorders, and subsequent TDV would provide critical guidance for targeted TDV prevention efforts for youth receiving mental health or substance abuse treatment. Finally, literature on the associations of substance use and TDV are lacking as much of the literature focuses on the role of any substance use [13] or age at first use [18] as predictors of TDV, with less known about substance abuse and dependence among this population.

While psychiatric disorders tend to co-occur, the types or clusters of disorders that may account for the relationship between poor mental health and TDV have not been examined. Differences in these associations for adolescent males and females are also critical to identify as they may represent different mechanisms that result in increased risk for TDV, with implications for designing targeted intervention strategies for adolescents. The goal of this study was to examine the predictive associations of psychiatric disorders including co-occurrence of such disorders on physical violence victimization and perpetration in adolescent dating relationships while accounting for adverse childhood experiences, to inform TDV prevention interventions. The current study uses a large, nationally representative sample from the United States which includes assessment of clinical criteria for a broad range of psychiatric disorders, childhood adversities and experiences of physical violence in dating relationships.

Methods

Data

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is based on a nationally representative, multi-stage clustered area probability sample of English-speaking respondents ages 18 and older living in the 48 contiguous United States [19]. Funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, the NCS-R study's original aims were to expand assessment for mental health disorders in the literature using rigorous methodologies and DSM-IV criteria, and understand trends in the prevalence and correlates of mental disorders over time [20]. The two-part survey was administered via one-time face-to-face interviews between February 2001 and April 2003. Part I, completed by 9,282 respondents, focused on diagnostic assessments of primary psychiatric disorders. Part II, completed by a sub-sample of 5,692 participants selected with known probabilities, assessed additional psychiatric disorders, risk factors, and outcomes. Recruitment and consent procedures were approved by Human Subjects Committees at Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan. Secondary data analyses were approved by the University of Pittsburgh.

Measures

Physical Dating Violence Perpetration and Victimization

Respondents were asked about dating relationships prior to age 21, defined as romantic relationships involving at least one date, with or without sexual activity. Those with histories of dating relationships indicated the age at which they started dating. Physical dating violence was assessed via items from the Conflict Tactics Scale [21]. Specifically, participants were asked whether they had ever experienced or ever perpetrated moderate (pushed, grabbed, shoved, threw something, slapped or hit) or severe (kicked, bit, hit with a fist, beat up, choked, burned or scalded, or threatened with a knife or gun) physical violence in a dating relationship. We conducted parallel analyses of three outcomes: victimization, perpetration and either victimization or perpetration.

Psychiatric Diagnoses

Psychiatric diagnoses were made using the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI)[20], a lay-administered structured instrument that generates diagnoses based on ICD-10 [22] and DSM-IV [23] criteria. The disorders considered here include major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, panic disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), intermittent explosive disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and alcohol and drug abuse and dependence. Disorders were also grouped into broader classes of internalizing and externalizing disorders, based on evidence from factor analysis and latent variable modeling of patterns of comorbidity that these groups share common etiologies [24-26]. As described elsewhere [20], the WMH-CIDI has shown to be valid and reliable for mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. Diagnoses of impulse control disorders have not yet been validated. Information on age of onset for each disorder was obtained by asking respondents if they remembered the exact age at which they first experienced symptoms. Those who did not remember an exact age are probed for lower and upper bounds using life course milestones (e.g. was it before you turned 18?) [27, 28]. These procedures have shown in experimental studies to produce plausible age of onset distributions in retrospective reports [29]. This information was used to identify those disorders which began prior to the respondents' age at first date.

Childhood Adversities

Based on previous research that adverse childhood experiences (ACE) are associated both with self-reported early onset psychiatric disorders recalled from childhood [16] and exposure to or perpetration of TDV [15], statistical controls for 12 ACE were included in all models. These included physical abuse by a caregiver, sexual assault or rape, childhood neglect, parental death, parental divorce, loss of contact with parents, family economic adversity, parental mental illness, parental substance abuse, criminality, domestic violence, and respondent serious physical illness. Items were derived from the Conflict Tactics Scale, a five-item scale about neglect and maltreatment by adult caregivers during childhood, and the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria [21, 30, 31].

Additional Covariates

All models controlled for sociodemographic characteristics including respondent age, sex, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Other), and parental education. Parental education was chosen instead of respondent education because the current study was interested in respondent experiences that occurred during adolescence, before age 21. Models additionally controlled for age at first date because participants who began dating earlier had a longer period of potential exposure to the outcome, relationship violence.

Analysis

Analyses were restricted to the sub-sample of participants who completed Part II of the interview, were age 21 or older at the time of the interview, had dated before age 21, and had complete data on dating violence variables (n=5112). Participants were considered positive for a psychiatric diagnosis if they indicated an onset of the disorder before the age of their first dating relationship. Logistic regression models were constructed to assess the relationship between psychiatric disorders and TDV between their age at first data and age 21, controlling for demographic characteristics, age at first date, and the number of childhood adversities that participants experienced. The relationship between psychiatric disorders and subsequent violence perpetration or victimization are presented as adjusted odds ratios (ORs), with confidence intervals and statistical tests calculated using the Taylor-series linearization method as implemented in the SUDAAN software package to account for the complex sampling strategy [32]. Significance was assessed via an alpha of 0.05.

Alternative models for the joint association of psychiatric disorders and any dating violence were compared using statistical indices of model fit (Akaike and Bayesian Information Criteria (AIC/BIC)). Specifically, we compared models with all 13 psychiatric disorders entered simultaneously as ‘main effects’, models with counts of disorders by disorder class, and models with both type of disorder and number of disorders as used by Green and colleagues in their study of co-occurring childhood adversities [16]. All models included statistical controls for demographic characteristics, age at first date and ACE. Finally, to draw out the clinical implications of these findings we examined variation in any physical dating violence involvement across five exhaustive and mutually exclusive clinical profiles, defined to reflect the most clinically significant distinctions among pediatric psychiatric patients as well as likely differences in the settings in which children and adolescents are treated, e.g. schools, pediatrician's offices, mental health clinics, and substance use treatment centers.

Results

Prevalence of physical violence in dating relationships and psychiatric disorders

In this sample, 13.9% reported physical violence victimization and 8.1% reported violence perpetration against a dating partner within a dating relationship before age 21. Females were more likely than males to report either violence victimization or perpetration (p<0.01), as were younger participants compared to older participants (p<0.01). African American and Hispanic participants were more likely than white participants to report violence victimization or perpetration (p<0.01). No statistically significant differences were noted across years of parental education (Table 1).

Table 1. Prevalence of Physical Dating Violence by demographic characteristics in the NCSR (N=5,112).

| Physical Dating Violence Victim |

Physical Dating Violence Perpetration |

Any Physical Dating Violence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % (95% CI) |

n | % (95% CI) |

n | % (95% CI) |

n | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 11.2 (9.4, 13.3) |

290 | 5.3 (4.4, 6.4) |

143 | 12.1 (10.3, 14.2) |

317 |

| Women | 16.3 (14.0, 18.8) |

584 | 10.6 (9.5, 11.9) |

406 | 19.4 (17.4, 21.5) |

693 |

| Age | ||||||

| 21-32 | 22.7 (19.5, 26.3) |

346 | 13.4 (11.4, 15.6) |

224 | 25.5 (22.2, 29.1) |

396 |

| 33-43 | 17.0 (13.9, 20.5) |

256 | 8.9 (7.1, 11.0) |

156 | 19.0 (16.2, 22.1) |

291 |

| 44-55 | 11.7 (9.6, 14.2) |

181 | 7.5 (6.0, 9.2) |

109 | 14.1 (11.9, 16.5) |

211 |

| 56-99 | 6.4 (5.0, 8.3) |

91 | 4.0 (3.0, 5.4) |

60 | 7.7 (6.1, 9.7) |

112 |

| Parental Education | ||||||

| 0-11 yrs | 12.7 (10.5, 15.4) |

268 | 8.0 (6.6, 9.6) |

181 | 14.7 (11.9, 16.0) |

307 |

| 12 yrs | 13.8 (11.9, 16.0) |

307 | 9.0 (7.5, 10.9) |

206 | 16.1 (14.0, 18.5) |

357 |

| 13-15 yrs | 17.0 (12.8, 22.3) |

118 | 9.2 (7.2, 11.8) |

69 | 19.1 (14.8, 24.2) |

137 |

| 16+ yrs | 14.2 (11.7, 17.0) |

181 | 6.2 (4.9, 7.8) |

93 | 16.0 (13.5, 18.9) |

209 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 14.3 (11.6, 17.4) |

94 | 9.7 (7.6, 12.3) |

56 | 17.4 (14.9, 20.3) |

108 |

| Black | 17.9 (14.2, 22.3) |

138 | 16.3 (12.8, 20.5) |

129 | 21.7 (17.8, 26.3) |

169 |

| Other | 18.4 (12.4, 26.3) |

50 | 11.3 (6.7, 18.5) |

32 | 21.1 (14.9, 29.0) |

58 |

| White | 13.0 (11.0, 15.5) |

592 | 6.5 (5.7, 7.5) |

332 | 14.6 (12.6, 17.0) |

675 |

Specific and social phobias were the most common internalizing disorders for both females (14.7% and 11.3%, respectively) and males (8.3% and 9.4%, respectively) prior to dating initiation. The most common externalizing disorders prior to dating among females were oppositional defiant disorder (4.0%) and attention deficit disorder (3.6%), while the most common externalizing disorders for males were intermittent explosive disorder (6.6%) and conduct disorder (5.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders prior to dating age.

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Prevalence* % (n) |

Any Physical Dating Violence % (n) |

Prevalence % (n) |

Any Physical Dating Violence % (n) |

|

| Internalizing disorders | ||||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 5.0 (228) | 34.4 (81) | 3.2 (116) | 20.5 (26) |

| Dysthymic Disorder | 1.6 (68) | 50.3 (35) | 0.8 (29) | 15.2 (5) |

| General Anxiety Disorder | 2.5 (112) | 43.3 (52) | 1.2 (45) | 23.3 (9) |

| Social Phobia | 11.3 (518) | 32.4 (166) | 9.4 (316) | 16.4 (50) |

| Specific Phobia | 14.7 (665) | 27.6 (196) | 8.3 (285) | 23.5 (57) |

| Panic Disorder | 1.9 (91) | 32.7 (33) | 1.0 (38) | 22.2 (9) |

| Bipolar Disorder (I or II) | 0.5 (27) | 33.9 (10) | 0.6 (25) | 34.4 (8) |

| Externalizing Disorders | ||||

| Intermittent Explosive Disorder | 2.9 (141) | 51.1 (73) | 6.6 (214) | 20.6 (52) |

| Attention Deficit Disorder | 3.6 (157) | 53.7 (84) | 4.9 (154) | 24.2 (41) |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 4.0 (165) | 60.9 (95) | 4.8 (155) | 27.9 (46) |

| Conduct Disorder | 2.8 (122) | 60.5 (70) | 5.6 (163) | 29.1 (56) |

| Alcohol Abuse | 0.9 (43) | 44.5 (21) | 2.2 (72) | 32.8 (19) |

| Drug Abuse | 0.7 (32) | 65.7 (20) | 1.4 (51) | 36.5 (18) |

Weighted percentage (N)

Prevalence is displayed as column percent, any relationship violence as row percent

Early onset psychiatric disorders and subsequent involvement in physical dating violence

Associations between early onset psychiatric disorders and physical dating violence victimization were found for 7 of the 13 disorders with statistically significant odds ratios ranging from 1.38 (social phobia) to 3.80 (drug abuse). A similar pattern was noted for violence perpetration with 8 statistically significant odds ratios ranging from 1.45 (specific phobia) to 3.41 (alcohol abuse) and any involvement in violence with 7 statistically significant odds ratios ranging from 1.40 (social phobia) to 3.40 (drug abuse). For all three outcomes, diagnosis of at least 1 internalizing disorder was associated with elevated odds of violence involvement of 1.51 to 1.62, while diagnosis of at least 1 externalizing disorder was associated with elevated odds of violence involvement of 2.23 to 2.66. For every one internalizing disorder present, participants experienced a 22% to 25% increase in the odds of violence involvement and for every one externalizing disorder present, participants experienced a 52% to 70% increase in odds of physical dating violence (Table 3).

Table 3. Psychiatric disorders as predictors of later involvement in physical dating violence victimization or perpetration.

| Physical Dating Violence Victim | Physical Dating Violence Perpetration | Any Physical Dating Violence | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Internalizing Disorders | |||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 1.33 (0.96, 1.86) | 1.02 (0.66, 1.58) | 1.33 (0.96, 1.84) |

| Dysthymic Disorder | 1.97 (1.00, 3.86) | 1.17 (0.62, 2.21) | 1.53 (0.77, 3.03) |

| General Anxiety Disorder | 1.65 (0.87, 3.12) | 1.62 (1.00, 2.61) | 1.84 (1.06, 3.19) |

| Social Phobia | 1.38 (1.14, 1.67) | 1.52 (1.21, 1.90) | 1.40 (1.19, 1.64) |

| Specific Phobia | 1.47 (1.16, 1.86) | 1.45 (1.06, 2.00) | 1.41 (1.15, 1.72) |

| Panic Disorder | 1.24 (0.75, 2.07) | 1.36 (0.78, 2.37) | 1.14 (0.73, 1.77) |

| Bipolar Disorder (I or II) | 1.99 (0.95, 4.16) | 2.30 (1.13, 4.68) | 1.66 (0.80, 3.46) |

| At least 1 internalizing disorder | 1.53 (1.26, 1.85) | 1.62 (1.31, 2.02) | 1.51 (1.30, 1.76) |

| # of internalizing disorders | 1.25 (1.12, 1.38) | 1.22 (1.12, 1.32) | 1.23 (1.13, 1.33) |

| Externalizing Disorders | |||

| Intermittent Explosive Disorder | 1.51 (0.98, 2.34) | 2.25 (1.62, 3.13) | 1.71 (1.17, 2.49) |

| Attention Deficit Disorder | 1.65 (1.19, 2.28) | 2.22 (1.70, 2.90) | 1.73 (1.34, 2.25) |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 2.64 (2.04, 3.43) | 2.69 (1.95, 3.72) | 2.63 (2.04, 3.40) |

| Conduct Disorder | 1.94 (1.33, 2.81) | 2.50 (1.68, 3.72) | 1.86 (1.27, 2.71) |

| Alcohol Abuse | 2.64 (1.72, 4.04) | 3.41 (1.75, 6.64) | 2.58 (1.61, 4.14) |

| Drug Abuse | 3.80 (2.06, 7.01) | 2.90 (1.45, 5.77) | 3.40 (1.90, 6.07) |

| At least 1 externalizing disorder | 2.23 (1.71, 2.91) | 2.66 (2.04, 3.47) | 2.29 (1.80, 2.92) |

| # of externalizing disorders | 1.52 (1.36, 1.70) | 1.70 (1.52, 1.90) | 1.54 (1.39, 1.72) |

| Final Model | |||

| # internalizing disorders | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 1.11 (1.01, 1.21) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.25) |

| # externalizing disorders * sex | |||

| Male | 1.22 (1.05, 1.43) | 1.47 (1.20, 1.80) | 1.28 (1.10, 1.49) |

| Female | 1.87 (1.58, 2.22) | 1.86 (1.59, 2.18) | 1.85 (1.55, 2.21) |

Note: All models account for demographic characteristics, age at first date, and the number of childhood adversities experienced

Joint associations of psychiatric disorders with involvement in physical dating violence

The best fitting model included a count of internalizing disorders, a count of externalizing disorders and a statistical interaction between the count of externalizing disorders and sex (Table 4). Each internalizing disorder was associated with a 14% increase in the odds of violence (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.04, 1.25). Associations with any physical dating violence were stronger for externalizing disorders, and significantly stronger for females (OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.55, 2.21) than for males (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.10, 1.49).

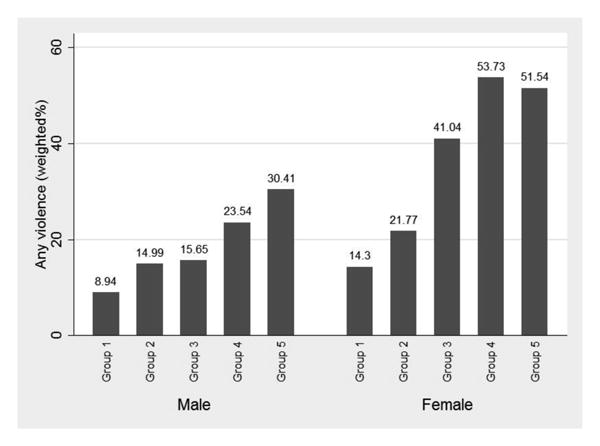

Clinical profiles of psychiatric disorders and risk for any physical dating violence

Figure 1 shows the actual (unadjusted) prevalence of any physical dating violence in each of five groups, separately for men and women. These groups include: 1) No psychiatric disorder; 2) Pure Internalizing: one or more internalizing disorders and no externalizing disorder; 3) ADHD: ADHD without a comorbid externalizing disorder; 4) Disruptive Behavior: at least one externalizing disorder other than ADHD and no substance use disorder; and 5) Substance Use Disorder: any substance use disorder regardless of other comorbidity.

Figure 1. Clinically Distinct Profiles of Psychiatric Disorders and Risk for Physical Dating Violence.

Group 1: No psychiatric disorder;

Group 2: Internalizing disorder only: one or more internalizing disorders and no externalizing disorder;

Group 3: ADHD: ADHD without a comorbid externalizing disorder and with/without a comorbid internalizing disorder;

Group 4: Disruptive Behavior: at least one externalizing disorder (except not ADHD or substance use disorder), with/without comorbid internalizing disorder;

Group 5: Substance Use Disorder: any substance use disorder regardless of other comorbidity

Compared with the ‘no disorder’ category, the prevalence of violence is higher across all four clinical categories for both males and females. While the highest prevalence is among those with a substance use disorder, prevalence is also elevated relative to the ‘no disorder’ category among those with disruptive behavior disorders who do not have a substance use disorder and among those with ADHD who do not have a disruptive behavior disorder.

Discussion

This study extends research on the impact of psychiatric disorders on physical violence in teen dating relationships by examining the associations of multiple disorders in a nationally representative sample with statistical adjustment for ACE. Studies have well documented the mental health impacts of TDV, with adolescents and young adults who have been in abusive relationships significantly more likely to experience depression, suicidality, PTSD and engage in risky substance use compared to their counterparts who have not been exposed to TDV [1, 4, 6-10], Several studies have assessed the opposite relationship, specifically that psychiatric disorders may be important risk factors for subsequent TDV [11, 12], but have yet to address the complex patterns of comorbidity among disorders [33]. The broad assessment of psychiatric disorders in this study, which were present prior to when participants initiated dating, allowed us to examine whether their association with physical violence in dating relationships was similar for a single group of disorders compared to a variety of disorders. If associations of psychiatric disorders with such violence were found for a single disorder or group of closely related disorders, then it could be possible that there is single distinct pathway through which mental health affects risk. Our findings suggest that this is not the case. Specifically, the best fitting model included both internalizing and externalizing disorders, with higher numbers of co-occurring disorders of either type associated with incremental increases in the odds of TDV. Consistent with previous research, externalizing disorders were the strongest predictors of physical dating violence [11, 34]. This is also consistent with studies of youth with externalizing disorders who have elevated risk for violence in general, not only in their dating relationships [35, 36]. Given the degree of psychiatric comorbidity experienced by adolescents with externalizing disorders, substance use disorders in particular, violence prevention efforts with youth in treatment for substance use and other mental health concerns are warranted.

Our findings also indicate that associations between psychiatric disorders and TDV may differ by sex. While both males and females in our sample experienced elevated odds of TDV for every one externalizing disorder they were diagnosed with, the magnitude of the association was stronger for females than for males. This supports findings from a 2001 study that found girls who had destructive responses to anger and engaged in physical fighting with same-sex peers to be at risk for TDV, while the only related significant predictor for boys was using alcohol [4]. The evidence suggests that the social implications of externalizing behaviors are to some extent gender specific [37]. For example, research suggests that females with externalizing disorders, unlike males, are more likely to have relationships with older partners, which has been shown to increase risk for TDV victimization [38-40].

Internalizing disorders were independently associated with physical dating violence after accounting for adverse childhood experiences and externalizing disorders but these associations were weaker than found with externalizing disorders. Social and specific phobia were associated with any violence in this sample, which may be related to maladaptive interpersonal relationships that are characteristic of individuals with those disorders [41]. In final adjusted models, the number of internalizing disorders remained a significant predictor with a 1.11 to 1.16 adjusted odds of violence involvement for each additional internalizing disorder during adolescence. While the odds of violence were notably smaller for those with internalizing disorders, the population prevalence of these disorders was higher than all externalizing disorders, indicating that number of dating violence cases as a result of internalizing disorders could be notable and warrants attention from prevention efforts. In contrast to the findings with externalizing disorders, no sex differences were noted. Also, contrary to other studies [12, 42], associations between major depressive disorder and physical dating violence were not statistically significant in this sample, which is notable given the attention paid to depression as an indicator for adolescents at risk for TDV [43]. The model testing the association between major depressive disorder and TDV controlled for exposure to ACE and age at first date, which have not been assessed in previous studies. Moreover, we are limited to early onset major depressive disorder by design - this study assessed psychiatric disorders that emerged prior to initiation of dating - and major depressive disorder has a later onset than other psychiatric disorders, typically emerging in the late 20s [44].The strength of our study is that we have all other internalizing disorders which are strong markers of psychiatric risk and tend to have an earlier onset than major depression.

The clinical implications of the model results are reflected in elevated prevalence of physical dating violence among all four clinical profiles relative to the no disorder group (Figure 1). These profiles are groups of individuals rather than groups of disorders and are defined to reflect the most clinically significant distinctions among pediatric psychiatric patients as well as likely differences in the settings in which children and adolescents are treated, e.g. schools, pediatrician's offices, mental health clinics, and substance use treatment centers. These findings have some key implications. First, the baseline level of risk for TDV among adolescents with no psychiatric disorders is still considerable, pointing to the importance of continuing violence prevention efforts with youth regardless of psychiatric diagnoses. Second, risk for violence is particularly high among adolescents with ADHD and are more prevalent among adolescents who only have internalizing disorders, relative to those with no disorder. Together, these findings suggest that clinical concern with TDV prevention interventions, including discussions with patients regarding safety in intimate relationships should not be focused only on youth known to be at elevated risk for violence (i.e. those with substance use or disruptive behaviors), but should be extended to a broader range of common psychiatric conditions than is generally recognized.

These findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, this study involved a single interview and did not include longitudinal follow-up. Thus, the associations presented here should not be interpreted as causal. However, participants indicated the age at which symptoms presented, a method that has been used in previous work, with the current study focusing on psychiatric disorders that occurred prior to the age at which respondents started dating (i.e. before they were at risk for TDV). This provides evidence for the temporality of our predictors (psychiatric disorders) and outcome (physical dating violence), The current study did not assess the mental health impacts of TDV, though this is another important focus of inquiry as violence and mental health are likely linked throughout the lifecourse. Psychiatric disorders, ACE and physical dating violence were measured retrospectively and therefore recall bias is a potential concern. However, psychiatric disorders were collected with a comprehensive battery of mental health measures and prevalence estimates found in the NCSR are comparable to other nationally representative studies, with the exception of substance abuse disorders which are lower than national estimates [20, 44]. One potential limitation of the NCS-R's assessment of substance use disorders include respondents not being assessed for dependence if they do not endorse abuse symptoms, which would result in an underestimation of the prevalence of substance use disorders in this sample [45]. However, as has been found in previous literature, the prevelance of dependence among those without a single abuse symptom is low, and not likely to affect estimates in the current study [46]. Potential recall bias impacting ACE and TDV prevalence would likely result in the underestimation of these exposure and outcomes. It is also possible that older participants would be less likely to report childhood adversities and violence because of differential participation or early death [16, 47]. Social desirability bias is also possible due to the sensitive nature of relationship violence, which would result in an underreporting of violence victimization and perpetration. Another limitation is that this study measured physical violence in dating relationships to the exclusion of sexual violence and emotional abuse, which are common facets of TDV and experienced more frequently by females than males. A measure of TDV that includes sexual violence and emotional abuse in adolescent relationships would allow more comprehensive explication of the sex differences that we have begun to explore here. Finally, the overlap and unique risk factors for violence victimization and perpetration are difficult to disentangle in the present analyses due to the difficulty in capturing the larger relationship context in the NCSR survey. These findings reflect risk for being in a relationship where there is physical violence, which is still important from both clinical and prevention perspectives. Further research is needed to understand the unique role psychiatric disorders play in violence victimization compared to violence perpetration. Despite these limitations, the strength and breadth of measurement for both psychiatric disorders and childhood adversities, the adjustment for a diverse array of childhood adversities, and the nationally representative sample allow us to make well supported conclusions about the risk for physical violence in dating relationships among adolescents with early onset psychiatric disorders.

This study adds to a growing body of research that considers the role of psychiatric disorders as potentially modifiable risk factors for TDV. Increased efforts to identify and treat early onset psychiatric disorders among youth, substance use and ADHD in particular, should also include assisting this group of vulnerable youth with healthy relationships skills building and related TDV prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/ORWH Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health (BIRCWH) K12HD043441 scholar funds to McCauley.

Footnotes

Contributing Authors: Joshua A. Breslau, ScD, PhD

RAND Corporation

4570 Fifth Ave #600, Pittsburgh, PA 15213

Naomi Saito, MS

Department of Public Health Sciences, University of California, Davis

1616 DaVinci, Davis, CA 95618

Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD

Department of Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Division of Adolescent Medicine, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC

3420 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213

Conflicts of Interest: On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA. 2001;286(5):572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vagi KJ, O'Malley Olsen E, Basile KC, Vivolo-Kantor AM. Teen Dating Violence (Physical and Sexual) Among US High School Students. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3577. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpern CT, Oslak SG, Young ML, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Partner Violence Among Adolescents in Opposite-Sex Romantic Relationships: Findings from the National Longitudianl Study of Adolescent Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(10):1679–1685. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foshee VA, Linder F, MacDougall JE, Bengdiwala S. Gender Differences in the Longitudinal Predictors of Adolescent Dating Violence. Preventive Medicine. 2001;32(2):128–141. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Silverman JG, Decker MR, Austin SB, McCormick MC, Virata MC, Miller E. Gender-Equitable Attitudes, Bystander Behavior, and Recent Abuse Perpetration Against Heterosexual Dating Partners of Male High School Athletes. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(10):1882–1887. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callahan MR, Tolman RM, Saunders DG. Adolescent Dating Violence Victimization and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2003;18(6):664–681. doi: 10.1177/0743558403254784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Hamby S. Recent Victimization Exposure and Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1149–54. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vázquez F, Torres A, Otero P. Gender-based violence and mental disorders in female college students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012;47(10):1657–1667. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal Associations Between Teen Dating Violence Victimization and Adverse Health Outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burton CW, Halpern-Felsher B, Rehm RS, Rankin SH, Humphreys JC. Depression and Self-Rated Health Among Rural Women Who Experienced Adolescent Dating Abuse: A Mixed Methods Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0886260514556766. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maas CD, Fleming CB, Herrenkohl TI, Catalano RF. Childhood Predictors of Teen Dating Violence Victimization. Violence Vict. 2010;25(2):131–149. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehrer JA, Buka S, Gortmaker S, Shrier LA. Depressive Symptomatology as a Predictor of Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence Among US Female Adolescents and Young Adults. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:270–276. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lormand DK, Markham CM, Perskin MF, Byrd TL, Addy RC, Baumler E, Tortolero SR. Dating Violence Among Urban, Minority, Middle School Youth and Associated Sexual Risk Behaviors and Substance Use. Journal of School Health. 2013;83(6):415–421. doi: 10.1111/josh.12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temple JR, Shorey RC, Fite P, Stuart GL, Le VD. Substance Use as a Longitudinal Predictor of the Perpetration of Teen Dating Violence. J Youth Adolescence. 2013;42:596–606. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9877-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller E, Breslau J, Chung WJ, Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Kessler RC. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of physical violence in adolescent dating relationships. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:1006–1013. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.105429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication i: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Sullivent EE. Age of Alcohol Use Initiation, Suicidal Behavior, and Peer and Dating Violence Victimization and Perpetration Among High-Risk, Seventh-Grade Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):297–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell BE, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(2):69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. International Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straus MA, Hamby S, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. International classification of diseases (ICD-10) Geneva, Switzerland: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington D.C: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, McLaughlin KA, Wall MM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Childhood maltreatment and the structure of common psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(2):107–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verona E, Javdani S, Sprague J. Comparing factor structures of adolescent psychopathology. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(2):545–551. doi: 10.1037/a0022055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Russo LJ, et al. Development of lifetime comorbidity in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):90–100. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustün TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–64. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knäuper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving accuracy of major depression age-of-onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1999;8(1):39–48. doi: 10.1002/mpr.55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendler KS, Silberg JL, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. The family history method: whose psychiatric history is measures? Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1501–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria. Reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34:1229–35. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.RTI. Software for Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN), Version 8.1. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of Twelve-month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wymbs BT, Molina B, Pelham W, Cheong J, Gnagy E, Belendiuk K, Walther C, Babinski D, Waschbusch D. Risk of Intimate Partner Violence among Young Adult Males with Childhood ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(5):373–383. doi: 10.1177/1087054710389987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brook DW, Brook JS, Rubenstone E, Zhang C, Saar NS. Developmental Associations Between Externalizing Behaviors, Peer Delinquency, Drug Use, Perceived Neighborhood Crime and Violence Behavior in Urban Communities. Aggress Behav. 2011;37(4):349–361. doi: 10.1002/ab.20397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor PJ, Silva PA. Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort: Results from the dunedin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):979–986. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kann RT, Hann FJ. Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Children and Adolescents: How Do Girls Differ From Boys? Journal of Counseling & Development. 2000;78(3):267–274. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb01907.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riehman KS, Bluthenthal R, Juvonen J, Morral A. Adolescent Social Relationships and the Treatment Process: Findings from Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33(4):865–896. doi: 10.1177/002204260303300405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanoss Marín B, Coyle KK, Gómez CA, Carvajal SC, Kirby DB. Older boyfriends and girlfriends increase risk of sexual initiation in young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(6):409–418. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(00)-00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gowen LK, Feltman SS, Diaz R, Yisrael DS. A Comparison of the Sexual Behaviors and Attitudes of Adolescent Girls with Older Vs. Similar-Aged Boyfriends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33(2):167–175. doi: 10.1023/B:JOYO.0000013428.41781.a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alden LE, Taylor CT. Interpersonal processes in social phobia. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(7):857–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keenan-Miller D, Hammen C, Brennan P. Adolescent psychosocial risk factors for severe intimate partner violence in young adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(3):456–63. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foshee VA, Benefield TS, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Suchindran C. Longitudinal predictors of serious physical and sexual dating violence victimization during adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39(5):1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demier O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cottler LB. Drug Use Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey: Have We Come a Long Way? JAMA Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):380–381. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Degenhardt L, Bohnert KM, Anthony JC. Assessment of cocaine and other drug dependence in the general population: “Gated” versus “ungated” approaches. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93(3):227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, et al. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. The Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]