Abstract

There is a lack of information on the molecular characterization of Ocimum species and hence, efforts have been made under the present study to characterize 17 Ocimum genotypes belonging to 5 different species (O. basilicum, O. americanum, O. sanctum, O. gratissimum and O. Polystachyon) through random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and inter simple sequence repeats (ISSR) markers. PCR amplification using 20 RAPD primers generated a total of 506 loci, of which 490 (96.47 %) loci were found polymorphic. The PIC value for RAPD ranged from 0.907 (OPF 14) to 0.954 (OPC 11) with an average of 0.937. The ISSR primers generated a total of 238 loci, of them 234 (98.17 %) loci were polymorphic. The PIC value ranged from 0.892 (UBC 808) to 0.943 (ISSR A12) with an average of 0.923. The average Jaccard’s similarity coefficient based on RAPD and ISSR analysis was 0.58 and 0.52, respectively. Clustering pattern of dendrogram generated using the pooled RAPD and ISSR data showed all Ocimum genotypes in their respective species groups at a cutoff value of 0.49 and 0.42, respectively. Many unique species-specific alleles were amplified by RAPD and ISSR markers. In both marker systems, a maximum number of unique alleles were observed in O. sanctum. The results of the present investigation provided valid guidelines for collection, conservation and characterization of Ocimum genetic resources.

Keywords: Basil, Diversity, ISSR, Ocimum, RAPD, Tulsi

Introduction

Interest in the exploitation of medicinal and aromatic plants as pharmaceuticals, herbal remedies, flavorings, perfumes and cosmetics, and other natural products has greatly increased in the recent years (Anonymous 1994; Ayensu 1996). India is an innate emporium of many medicinal plants and most of such plants are used traditionally. Ocimum like other medicinal plants are highly valued medicinal plant in the traditional Ayurvedic and Unani system of medicine for its range of therapeutic activities. It belongs to the family Lamiaceae, which has close to 252 genera and 6,700 species (Mabberley 1997), most of which are used for medicinal purpose (Wren 1968) and find diverse uses in the indigenous system of medicine in many countries like Africa, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Burma, India, Malaya, Pacific Islands and Sri Lanka (Pushpangadan and Sobti 1977; Balyan and Pushpangadan 1988). Many species of this genus are also used as pot herbs.

O. sanctum L. (Tulsi), O. gratissimum (Ram Tulsi, 2n = 40), O. canum (Dulal Tulsi; 2n = 24), O. basilicum (Ban Tulsi), O. polystachyon (2n = 60), O. americanum and O. micranthum are examples of known important species of genus Ocimum which nurture in different parts of the world. Plants have square stems, fragrant opposite leaves and whorled flower on spiked inflorescence. Basic chromosome number in Ocimum species is x = 12 (Carovic et al. 2010), whereas, O. basilicum and O. americanum are reported to be tetraploid (2n = 4x = 48) and hexaploid (2n = 6x = 72), respectively (Sobti and Pushpangadan 1979). O. sanctum is perennial shrub with a basic chromosome number of n = 8 (Darrah 1980; Pushpangadan and Bradu 1995).

Important essential oil constituents reported from Ocimum species include linalool, linalyl acetate, geraniol, citral, camphor, eugenol, methyl eugenol, methyl chavicol, methyl cinnamate, thymol, safrole etc., which are of immense value in the perfumery and cosmetic industries (Balyan and Pushpangadan 1988) and also shown to have antibacterial activity. Among Ocimum species, common basil viz. O. basilicum is economically the most important one. The aromatic leaves of basil are used fresh and dried as flavoring agents or spices in a wide variety of foods. Volatile oils of basil are used to flavor foods, dental and oral products, and in fragrances. Basil is also used in traditional ceremonial rituals. It also contains biologically active constituents that are insecticidal, nematicidal, fungistatic, or antimicrobial. O. sanctum’ possesses antifertility, anticancer, antidiabetic, antifungal, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, antiemetic, antispasmodic, analgesic and antitussive properties (Singh et al. 2011). The two main morphotypes of O. sanctum cultivated in India are (1) green-leaved plants known as Sri Tulsi (Green Tulsi) and (2) purple-leaved plants known as Krishna Tulsi (Black Tulsi) (Raina et al. 2013).

Because of its potential uses as a traditional medicine, incorporation of Ocimum species into agro forestry systems would not only make the species accessible to the majority of the rural population that uses it but also contribute to its genetic conservation. However, before this programme of widespread domestication of the species is implemented, it would be important to determine its genetic diversity so that only elite genotypes are multiplied and conserved (Harisaranraj et al. 2008).

Molecular markers have proven to be powerful tools in the assessment of genetic variation and in the elucidation of genetic relationships within and among species. Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers have been used to characterize the genetic diversity in a number of medicinal and aromatic plants including Ocimum (Satovic et al. 2002; Vieira et al. 2003; Singh et al. 2004; De Masi et al. 2006). The advantage of RAPDs is that they require no prior sequence information (Palumbi 1996). Inter simple sequence repeats (ISSR) technique is also a PCR-based method, which involves amplification of DNA segment present at an amplifiable distance in between two identical microsatellite repeat regions oriented in opposite direction. It is a reproducible, highly polymorphic marker and is useful in studies of genetic diversity, phylogeny, gene tagging, genome mapping and evolutionary biology (Reddy et al. 2002). There is a lack of information on the molecular characterization of the Ocimum species. To accomplish the above aim, the present investigation was carried out with RAPD and ISSR.

Materials and methods

Plant material and DNA extraction

Seeds of 17 genotypes belonging to 5 species were procured from AICRP on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Anand Agricultural University, Anand (Table 1). Ten plants of each accession were grown in pots for DNA isolation. Two grams of young leaf tissue was harvested from each plant and frozen in liquid nitrogen for DNA extraction. DNA from young leaves of a bulk of ten plants was isolated using CTAB technique (Doyle and Doyle 1987), purified and quantified using Nanodrop N.D.1000 (Software V.3.3.0, Thermo Scientific, USA). DNA was diluted to 20 ng/μl with T10E1 buffer and stored at 4 °C.

Table 1.

Details of genotypes used for RAPD and ISSR based characterization

| Sr. no. | Genotypes | Species name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Green Tulsi | O. sanctum |

| 2 | Black Tulsi | |

| 3 | Kapur Tulsi | |

| 4 | Closimum | O. gratissimum |

| 5 | Van Tulsi | |

| 6 | Aajlo | O. americanum |

| 7 | Aavachi Bavachi | O. polystachyon |

| 8 | SBOB-1 | O. basilicum |

| 9 | SBOB-2 | |

| 10 | Walmi | |

| 11 | Violet | |

| 12 | Jodhpur | |

| 13 | Jhadol Udaipur | |

| 14 | Solan Serrated | |

| 15 | IC-283658 | |

| 16 | Long Spike | |

| 17 | Anand Local |

RAPD and ISSR amplification

A total of 120 primers (100 RAPD and 20 ISSR) were used in PCR amplification. RAPD primers used in this study were selected from the study of Singh et al. (2004), while ISSR primers of UBC series were selected from the report of Aghaei et al. (2012). PCR amplification was carried out using 200 µl PCR tubes (Axygen, USA) in thermocyclers (Biometra, Germany). PCR amplification was carried out in a 25 μl reaction volume containing 2.5 μl template DNA (50 ng), 1× Dream Taq PCR buffer with MgCl2 (Fermentas, USA), 0.4 μl (5 U/μl) Taq polymerase (Fermentas, USA), 0.5 μl (2.5 mM each) dNTPs (Fermentas, USA) and 1 μl (10 pmol/μl) primer (MWG Biotech, Germany). RAPD-PCR was performed at an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 38 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 38 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1.2 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The optimal annealing temperature for ISSR primers was found to vary according to the base composition of the primers. Therefore, ISSR-PCR was performed at an initial denaturation temperature of 94 °C for 5 min, 38 cycles of 94 °C for 50 s, 35–58 °C (depending on primer sequence) for 60 s and 72 °C for 1.2 min and a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min.

Agarose gel electrophoresis

Amplified products were electrophoresed in 1.5 % agarose in 1× TBE buffer. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and documented using gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Each experiment was repeated two times with each primer and those primers which gave reproducible fingerprints (DNA bands) were only considered for the data analysis.

Data analysis

For each genotype, each fragment/band that was amplified using ISSR and RAPD primers was treated as unit character. Unequivocally reproducible bands were scored and entered into a binary character matrix (1 for presence and 0 for absence). The pairwise genetic similarity coefficient was calculated using Jaccard’s coefficient (Jaccard 1908) by the SIMQUAL program of NTSYS-pc software version 2.02 (Rohlf 1998). A dendrogram was constructed based on the matrix of distance using unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA).

To compare the efficiency of primers, polymorphic information content (PIC), as a marker discrimination power, was computed using the formula PIC = , where P i is the frequency of the ith allele at a given locus (Anderson et al. 1993). The PIC values are commonly used in genetics as a measure of polymorphism for a marker locus using linkage analysis. Correlation between the matrices obtained with both marker types (RAPD and ISSR primers) was estimated by means of Mantel test using MxComp module of NTSYSpc (Mantel 1967). Principal component analysis was carried out using the EIGEN module of NTSYSpc 2.02.

Results

Performance of different marker systems

ISSR analysis

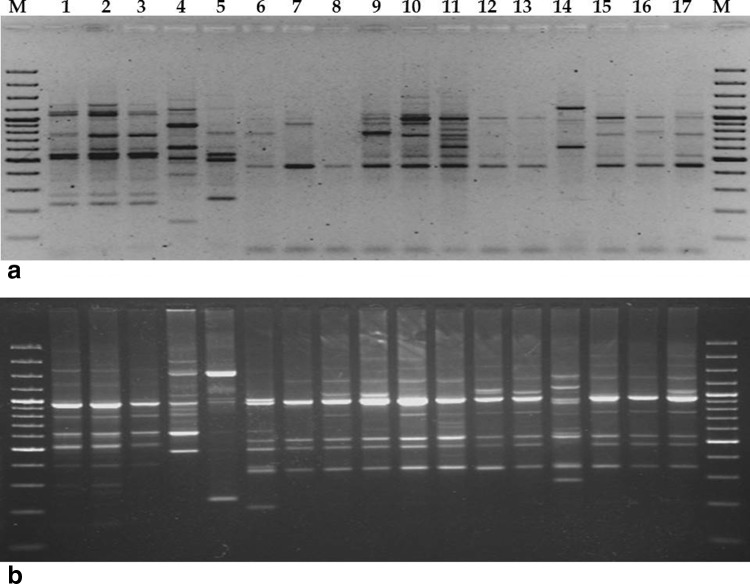

Among 20 ISSR primers used in this study, 12 primers detected a total of 238 amplicons in 17 genotypes, out of which 234 (98.17 %) were polymorphic (Fig. 1a; Table 2). Out of 12 primers, eight primers were 100 % polymorphic. The number of total amplicons varied from 13 (UBC 808) to 32 (ISSR A12) with an average of 19.5 loci per primer, and sizes ranged from 89 (UBC 807) to 2,940 bp (UBC 841). The number of polymorphic amplicons ranged from 12 (UBC 808) to 31 (ISSR A12) with an average of 19.5 polymorphic loci per marker. The PIC value ranged from 0.892 (UBC 808) to 0.943 (ISSR A12) with a mean of 0.923. Marker index value for ISSR was 17.99. ISSRs were also highly efficient with respect to molecular species identification.

Fig. 1.

a ISSR profile 17 Ocimum genotypes generated by UBC 807 and b RAPD profile of 17 Ocimum genotypes generated by OPD 10

Table 2.

Numerical data as obtained from PCR amplification by ISSR primers among Ocimum species

| Sr. no. | Locus name | Sequence 5′–3′ | GC content (%) | Tm | Molecular weight (bp) | No. of loci | No. of polymorphic loci | Percent polymorphism (%) | PIC value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UBC 443 | ACACACACACACACACACT | 47 | 49 | 453–2,159 | 18 | 17 | 94.44 | 0.909 |

| 2 | UBC 807 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGT | 47 | 45 | 89–1,556 | 22 | 22 | 100 | 0.930 |

| 3 | UBC 808 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAG(CT)C | 53 | 51 | 604–2,224 | 13 | 12 | 92.30 | 0.892 |

| 4 | UBC 818 | CACACACACACACAG | 53 | 42 | 342–1,835 | 18 | 17 | 94.44 | 0.915 |

| 5 | UBC 825 | ACACACACACACACACT | 47 | 45 | 446–2,279 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 0.934 |

| 6 | UBC 834 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAG(CT)T | 47 | 49 | 392–2,597 | 19 | 19 | 100 | 0.934 |

| 7 | UBC 840 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAYT | 47 | 45 | 222–1,952 | 18 | 18 | 100 | 0.919 |

| 8 | UBC 841 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAYC | 53 | 47 | 189–2,940 | 22 | 22 | 100 | 0.937 |

| 9 | UBC 855 | ACACACACACACACACYT | 47 | 45 | 238–2,284 | 15 | 15 | 100 | 0.908 |

| 10 | ISS RA7 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGT | 48 | 52 | 254–1,720 | 21 | 21 | 100 | 0.930 |

| 11 | ISS RA12 | GAGAGAGAGAGACC | 57 | 40 | 225–1,984 | 32 | 31 | 96.88 | 0.943 |

| 12 | CTC 4RC | CTCCTCCTCCTCRC | 69 | 44 | 307–2,587 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 0.922 |

| Total | – | 238 | 234 | – | – | ||||

| Average | 313–176 | 19.8 | 19.5 | 98.17 | 0.923 | ||||

RAPD analysis

In present study, 17 accessions belonging to 5 different basil species were surveyed with two marker systems, i.e., RAPD and ISSR. For RAPD analysis, among 100 arbitrary primers tested, 20 primers generated 506 loci (Fig. 1b; Table 3). Of these, 490 loci were polymorphic with an average polymorphism of 96.47 %. Out of 20 primers, nine primers were 100 % polymorphic. The molecular size of the amplified RAPD products ranged from 152 bp (OPC 18) to 3,176 bp (OPF 5). The number of total amplicons varied from 16 (OPA 3) to 33 (OPC 11) with an average of 25.3 loci per primer. The number of polymorphic amplicons ranged from 15 (OPA 2 and OPA 3) to 33 (OPC 11) with an average of 24.5 loci per primer. OPC 11 showed the highest PIC (0.954), while it was lowest for OPF 14 (0.907) with an average of 0.937. Marker index value for RAPD was 22.95.

Table 3.

Numerical data as obtained from PCR amplification by RAPD primers among Ocimum species

| Sr. no | Locus name | Sequence 5′–3′ | GC content (%) | Molecular weight (bp) | No. of loci | No. of polymorphic loci | Polymorphism (%) | PIC value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OPA 2 | TGCCGAGCTG | 70 | 362–2,312 | 17 | 15 | 88.23 | 0.93 |

| 2 | OPA 3 | AGTCAGCCAC | 60 | 333–1,607 | 16 | 15 | 93.75 | 0.92 |

| 3 | OPA 4 | AATCGGGCTG | 60 | 189–2,746 | 23 | 19 | 82.61 | 0.94 |

| 4 | OPA 9 | GGGTAACGCC | 70 | 266–2,923 | 19 | 18 | 94.74 | 0.92 |

| 5 | OPA 11 | CAATCGCCGT | 60 | 206–2,518 | 22 | 21 | 95.45 | 0.94 |

| 6 | OPC 4 | CCGCATCTAC | 60 | 236–2,717 | 30 | 29 | 96.67 | 0.94 |

| 7 | OPC 11 | AAAGCTGCGG | 60 | 214–2,812 | 33 | 33 | 100 | 0.95 |

| 8 | OPC 14 | TGCGTGCTTG | 60 | 237–3,073 | 31 | 30 | 96.77 | 0.95 |

| 9 | OPC 15 | GACGGATCAG | 60 | 602–2,625 | 32 | 32 | 100 | 0.94 |

| 10 | OPC 18 | TGAGTGGGTG | 60 | 152–2,067 | 30 | 30 | 100 | 0.94 |

| 11 | OPD 2 | GGACCCAACC | 70 | 319–2,566 | 27 | 27 | 100 | 0.93 |

| 12 | OPD 3 | GTCGCCGTCA | 70 | 248–2,795 | 29 | 29 | 100 | 0.94 |

| 13 | OPD 10 | GGTCTACACC | 60 | 176–1,912 | 27 | 26 | 96.30 | 0.93 |

| 14 | OPD 11 | AGCGCCATTG | 60 | 204–2,256 | 25 | 25 | 100 | 0.94 |

| 15 | OPD 18 | GAGAGCCAAC | 60 | 373–1,919 | 24 | 23 | 95.83 | 0.92 |

| 16 | OPD 20 | ACCCGGTCAC | 70 | 266–2,270 | 28 | 28 | 100 | 0.95 |

| 17 | OPE 9 | CTTCACCCGA | 60 | 187–2,801 | 34 | 32 | 94.12 | 0.94 |

| 18 | OPF 5 | CCGAATTCCC | 60 | 285–3,176 | 22 | 22 | 100 | 0.93 |

| 19 | OPF 8 | GGGATATCGG | 60 | 269–2,013 | 20 | 19 | 95 | 0.92 |

| 20 | OPF 14 | GGTCTAGAGG | 60 | 336–2,112 | 17 | 17 | 100 | 0.91 |

| Total | – | 506 | 490 | – | – | |||

| Average | 176–3,176 | 25.3 | 24.5 | 96.47 | 0.937 | |||

Using ISSR and RAPD for Ocimum DNA analysis, species-specific DNA fragments were identified. ISSR and RAPD amplicons occurring only within a given species and showing no polymorphism at the intra-specific level were considered to be species-specific markers. A total of four ISSR primers produced species-specific amplicons with maximum of three amplicons in O. sanctum. However, no species-specific alleles were detected in O. basilicum (Table 4). Similarly, out of the 20 RAPD primers analyzed, three primers produced species-specific amplicons (Table 4). The primer OPF 8 generated two amplicons (1,180 bp and 269 bp), specific to O. sanctum and O. gratissimum, respectively. O. americanum and O. polystachyon were not considered in RAPD- and ISSR-based species-specific allele detection as both species were represented by only single genotype each.

Table 4.

Ocimum species-specific bands as revealed by RAPD and ISSR markers

| Ocimum species | Characterized by the RAPD markers (bp) | Characterized by the ISSR markers (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| O. Sanctum | OPD 18–439 | UBC 808–520 |

| OPF 8–1,180 | UBC 825–450 | |

| UBC 840–1,110 | ||

| O. gratissimum | OPF 8–269 | CTC 4RC–1,180 |

| O. basilicum | OPC 4–1,370 | – |

RAPD-based cluster analysis

Jaccard’s similarity coefficients based on RAPD markers among the all pair-wise combinations of genotypes ranged from 0.21 [between Van Tulsi (O. sanctum) and Aavachi Bavachi (O. polystachyon)] to 0.90 (between Long Spike and Anand Local) with an average value of 0.39. O. basilicum group showed a high genetic similarity index as compared to other species (Table 5). Genetic similarity within the O. basilicum genotypes varied from 0.36 (SBOB-1 and Solan Serrated) to 0.90 (Long Spike and Anand Local), and average genetic similarity coefficient was 0.58.

Table 5.

Jaccard’s similarity coefficient based on RAPD analysis in 17 Ocimum genotypes

| Genotypes | Green Tulsi | Black Tulsi | Kapur Tulsi | Closimum | Van Tulsi | Aajlo | Aavachi Bavachi | SBOB-1 | SBOB-2 | Walmi | Violet | Jodhpur | Jhadol Udaipur | Solan Serrated | IC-283658 | Long Spike | Anand Local |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Tulsi | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| Black Tulsi | 0.88 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Kapur Tulsi | 0.75 | 0.78 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Closimum | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| Van Tulsi | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Aajlo | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Aavachi Bavachi | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.38 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| SBOB-1 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| SBOB-2 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.62 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Walmi | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Violet | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Jodhpur | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 1.00 | |||||

| Jhadol Udaipur | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 1.00 | ||||

| Solan Serrated | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 1.00 | |||

| IC-283658 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 1.00 | ||

| Long Spike | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.82 | 1.00 | |

| Anand Local | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 1.00 |

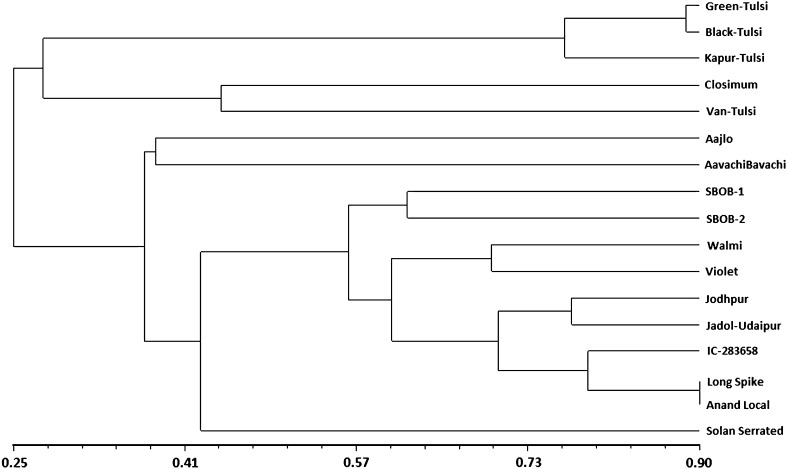

The UPGMA clustering algorithm based on RAPD data grouped 17 accessions into six groups at an average cutoff value of 0.49 (Fig. 2). The cophenetic correlation was calculated and indicated a very good fit (r = 0.98). RAPD clearly distinguished all the species. Among the clusters, most of the samples from O. basilicum were clustered into group two (9 samples) than the other, while group seven contained three genotypes all belonging to O. sanctum. However, a genotype namely Solan serrated was found quite distinct from the other cultivars of O. basilicum as it clustered apart from the group two. Remaining groups contained only a single sample each. Two genotypes Closimum and Van Tulsi belonging to O. gratissimum were grouped as different clusters.

Fig. 2.

UPGMA cluster analysis of 17 Ocimum genotypes with Jaccard’s similarity coefficient of RAPD

ISSR-based cluster analysis

The values of similarity coefficient obtained in ISSR analysis ranged from 0.13 (between Closimum and Aavachi) to 0.96 (between Green Tulsi and Black Tulsi) among the genotypes studied (Table 6). The average similarity coefficient among genotypes was 0.35. Within the O. basilicum genotypes, genetic similarity ranged from 0.29 (SBOB-1 and Solan Serrated) to 0.84 (Long Spike and Anand Local) with an average genetic similarity coefficient of 0.52.

Table 6.

Jaccard’s similarity coefficient based on ISSR analysis in 17 Ocimum genotypes

| Genotypes | Green Tulsi | Black Tulsi | Kapur Tulsi | Closimum | Van Tulsi | Aajlo | Aavachi Bavachi | SBOB-1 | SBOB-2 | Walmi | Violet | Jodhpur | Jhadol Udaipur | Solan Serrated | IC-283658 | Long Spike | Anand Local |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Tulsi | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| Black Tulsi | 0.96 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Kapur Tulsi | 0.84 | 0.86 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Closimum | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| Van Tulsi | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.48 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Aajlo | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Aavachi Bavachi | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| SBOB-1 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| SBOB-2 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Walmi | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Violet | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.71 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Jodhpur | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 1.00 | |||||

| Jhadol Udaipur | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 1.00 | ||||

| Solan Serrated | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 1.00 | |||

| IC-283658 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.72 | 1.00 | ||

| Long Spike | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 1.00 | |

| Anand Local | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 1.00 |

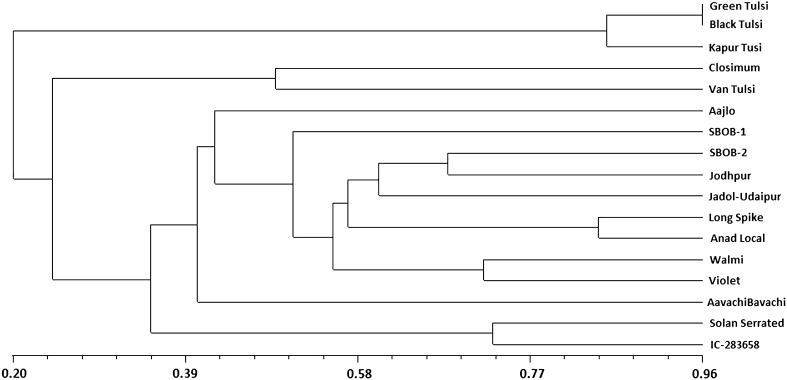

Based on the genetic similarities, seventeen genotypes were grouped into six major clusters at a cutoff value of 0.42 (Fig. 3) and the cophenetic correlation showed a good fit (r = 0.97). The clustering of genotypes proved the suitability of ISSRs in detecting alleles characteristic of genotypes from different species. Group two contained only one genotype of O. polystachyon that accommodating itself in O. basilicum group, consequently dividing the O. basilicum into two clusters (1 and 3). The cluster one consisted of two genotypes while cluster 3 was composed of eight cultivars from O. basilicum. Unlike RAPD, both genotypes of O. gratissimum grouped in one cluster. In contrast to RAPD, O. polystachyon was found closer to O. basilicum instead of O americanum in ISSR analysis. Solan serrated and IC-283658 belonging to O. basilicum species were more diverse among all O. basilicum genotypes.

Fig. 3.

UPGMA cluster analysis of 17 Ocimum genotypes with Jaccard’s similarity coefficient of ISSR

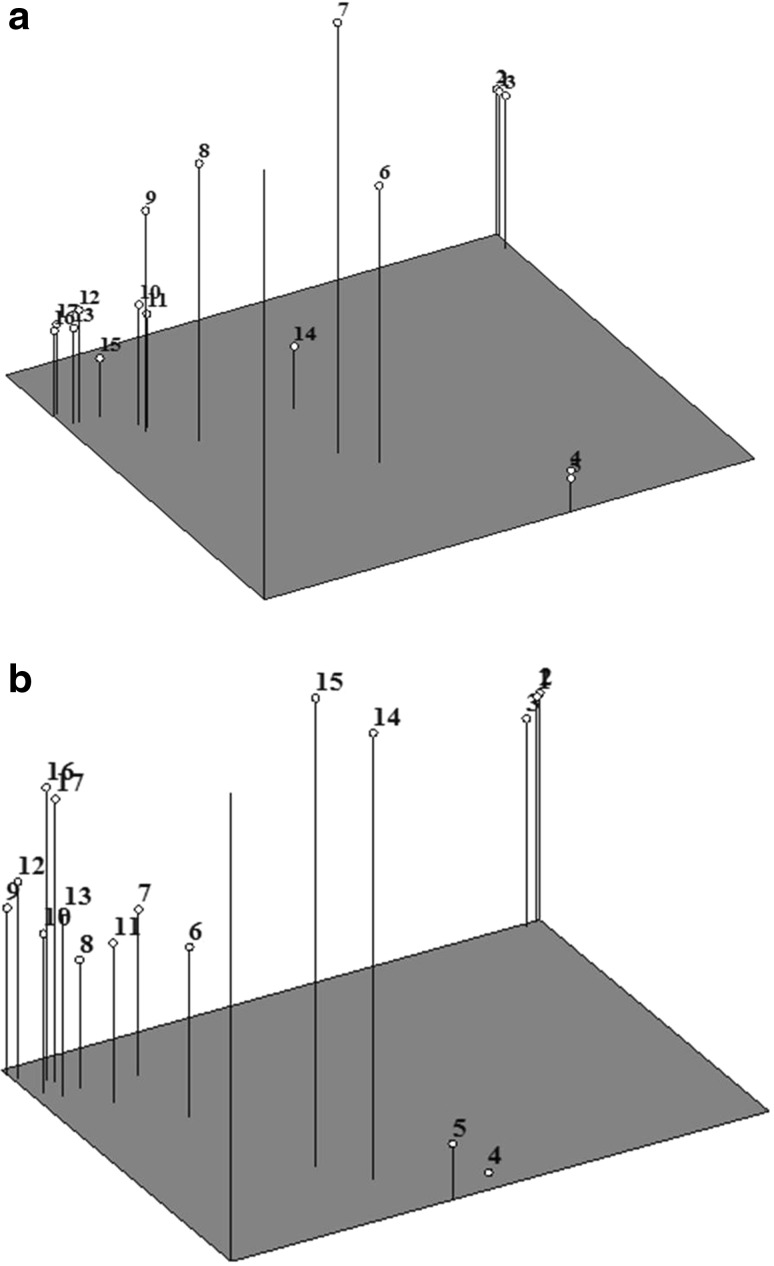

RAPD- and ISSR-based principal component analysis (PCA)

The result of PCA based on RAPD markers was comparable to the cluster analysis (Fig. 4a). The first three coordinate axis accounted for 65 % (first axis = 31 %) of the variation observed. The RAPD-based PCA revealed that the genotypes belonging to a particular cluster were grouped together in the PCA plot. It showed that the O. sanctum genotypes clustered together, whereas O. basilicum genotypes clustered as a second group. Solan serrated belonging to O. basilicum species was more diverse among the all O. basilicum genotypes. PCA analysis with ISSR markers revealed that the first three coordinate axes of analysis accounted for 63 % (first axis = 28 %) variation, and clustered all of the varieties in four clades (Fig. 4b). These results are consistent with those obtained with the ISSR dendrogram, indicating substantial genetic diversity among genotypes. It is also evident from genotypic data of both markers’ system that genotypes are fairly dispersed on PCA plots, which reflects a good genetic base. Mantel test-based correlation of similarity matrices generated by individual marker systems was 0.86.

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional plot by PCA using a RAPD primers and b ISSR primers; 1 Green Tulsi, 2 Black Tulsi, 3 Kapur Tulsi, 4 Closimum, 5 Van Tulsi, 6 Aajlo, 7 Aavachi Bavachi, 8 SBOB-1, 9 SBOB-2, 10 Walmi, 11 Violet, 12 Jodhpur, 13 Jhadol Udaipur, 14 Solan Serrated, 15 IC-283658, 16 Long Spike, 17 Anand Local

Discussion

Little published information can be found about assessment of molecular diversity in Ocimum using a PCR-based approach (Lal et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2013). The intrinsic genetic diversity in present study on Ocimum accessions was apparent from the analysis of their RAPD and ISSR profiles and from the dendrogram generated where all the accessions had unambiguously separated from each other. RAPD and ISSR studies have been widely used for population genetic studies in both wild (Dikshit et al. 2007, Yao et al. 2008) and cultivated plants (Nagaoka and Ogihara 1997; Sikdar et al. 2010). Generally, all these studies have reported that ISSR primers produce more reliable and reproducible bands than RAPD primers. In the present study, however, it was observed that once the PCR conditions are well set, high reproducibility for both RAPD and ISSR markers can be obtained. In general, all 22 markers used in this study produced clear consistent and reproducible amplification profiles.

Performance of different marker systems

The plants of Ocimum species are valued as spice and herbal medicine in India (Harisaranraj et al. 2008). Driven by commercial incentives, the wild populations of these species have been threatened with depletion in recent years due to excessive harvesting. In the present study, 17 Ocimum accessions belonging to 5 species were studied with 2 different marker systems, i.e., RAPD and ISSR for genetic diversity analysis. ISSR showed the highest polymorphism level (98.17 %) than RAPD (96.47 %). The results were consistent with genetic diversity analysis of Ocimum by Chen et al. 2013. Similarly, Lal et al. (2012) carried out ISSR analysis in six species of Ocimum and found 100 % polymorphism. High polymorphism of ISSR and RAPD markers was also reported in many previous studies, for examples, RAPD of Melocanna baccifera (Lalhruaitluanga and Prasad 2009), ISSR of Jatropha curcas accessions (Grativol et al. 2011). Moreover, Dutta et al. (2010) checked the efficiency of three PCR-based markers (ISSR, RAPD and SSR) in chickpea and pigeon pea and reported higher polymorphism in all three markers. High levels of polymorphism found in the present work showed that both markers are suitable for genetic diversity studies and are equally effective to differentiate the closely related cultivars of Ocimum.

PIC analysis can be used to evaluate markers so that the most appropriate marker can be selected for genetic mapping and phylogenetic analysis (Anderson et al. 1993; Powell et al. 1996). Though, RAPDs cover the whole genome for amplification, ISSR amplifies the regions between two microsatellites, but the average PIC of both marker systems was higher and almost comparable. The higher PIC value for the RAPD obtained makes its MI (measure of the efficiency to detect polymorphism) much higher than that of the ISSRs used in the present study. This was consistent with previous reports in Ocimum (Lal et al. 2012). The high MI is the reflection of efficiency of marker to simultaneously analyze a large number of bands, rather than level of polymorphism detected (Powell et al. 1996).

Both the DNA marker analysis methods allowed us to identify species specific markers. In both marker systems, the highest number of species-specific loci was revealed in O. sanctum. The results of this study support that both marker types are powerful tools in resolving species/inter-species status of Ocimum and in deciding the distinctness of different genera within a family and species-specific alleles can be converted into co-dominate SCAR markers for further characterization of the Ocimum species from the different geographical regions.

Genetic diversity analysis of basil accessions

Comparison of genetic similarity coefficients of both RAPD and ISSR markers showed that the former ranged from 0.21 to 0.90, while the latter varied from 0.13 to 0.96. Thus, both RAPD and ISSR markers showed polymorphisms and large variability; and distinguishing genotypes clearly. High level of genetic dissimilarity among Ocimum species demonstrates that the level of genetic variation in the species is substantial and indicated that genetic base is quite broad. However, the wide range of similarity (0.13–0.96) was observed in ISSR analysis indicating that higher genetic variations existed in the target genome regions than those targeted by RAPD (0.21–0.90). In the present study, genetic distance values were well correlated between marker types. Comparison of different marker systems for diversity in Ocimum revealed congruent diversity estimates for different types of markers (Chen et al. 2013). Furthermore, six groups were obtained using ISSR or RAPD. This was consistent with the higher correlation (r = 0.86) of the ISSR and RAPD similarity matrices and their cophenetic values. High correlation values between two marker systems have been reported earlier in many plants species (Kesari et al. 2010; Yildiz et al. 2011). In both the UPGMA-based dendrograms, the genotypes under the same species were clustered together. For RAPD and ISSR markers, a high reproducibility in dendrogram topologies was obtained, with some differences in ISSR where O. polystachyon shuffled between O. basilicum genotypes. Both markers aim to amplify a different region of the genome, and thus it is reasonable that there are some fine differences between the two dendrograms based on an individual data set. In previous reports, RAPD and ISSR also showed some differences in the positioning of few individuals (Kesari et al. 2010). In ISSR-based dendrogram, almost all accessions belonging to O. basilicum were clustered in Group 3, except two accessions, Solan serrated and IC-283658, indicating that these two accessions are more distantly related to the other O. basilicum accessions analyzed and probably may be because of some unique repeat sequences. In the present investigation, the mean similarity index of ISSR was 0.35 which is quit low as compared to the mean similarity index reported by Aghaei et al. (2012) where mean similarity index was 0.735 with same 12 ISSR primers on 50 genotypes of O. basilicum. Difference in number of species studied and region of collection may be probable reason for the difference in the similarity index. Lal et al. (2012) also reported a low mean similarity index (0.39).

Principal coordinate analysis was used to illustrate the multiple dimensions of the distribution of the genotypes in a scatter-plot. Separation of individual accessions to their respective clusters as is evident from the UPGMA dendrogram as well as PCA was observed for both the markers with some differences. This multivariate approach was used to complement the information obtained from the cluster analysis methods because it is more informative regarding distances among major groups (Taran et al. 2005).

Conclusion

It can be concluded from the present study that both RAPD and ISSR produced many unique alleles which can be converted in SCAR to develop species-specific diagnostic markers.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Unit, Anand Agricultural University, Anand for providing the seed material.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Aghaei M, Darvishzadeh R, Hassani A. Molecular characterization and similarity relationships among Iranian basil (O. basilicum) accessions using inter simple sequence repeat markers. Artig Cient. 2012;43(2):312–320. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JA, Churchill GA, Autrique JE, Tanksley SD, Sorrells ME. Optimizing parental selection for genetic linkage maps. Genome. 1993;36:181–186. doi: 10.1139/g93-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous (1994) Ethnobotany in the search for new drugs. Ciba Foundation Symposium, vol 188. Wiley, New York

- Ayensu ES (1996) World medicinal plant resources. In: Chopra VL, Khoshoo TN (eds) Conservation for productive agriculture. ICAR, New Delhi, India, pp 11–42

- Balyan SS, Pushpangadan P. A study on the taxonomical status and geographic distribution of the genus Ocimum. The PAFAI J. 1988;10(2):13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Carovic SK, Liber Z, Besendorfer V, Javornik B, Bohanec B, Kolak I, Satovic Z. Genetic relations among basil taxa (Ocimum L.) based on molecular markers, nuclear DNA content, and chromosome number. Plant Syst Evol. 2010;285:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s00606-009-0251-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Dai TX, Chang YT, Wang SS, Ou SL, Chuang WL, Chuang CY, Lin YH, Lin YH, Ku HM. Genetic diversity among Ocimum species based on ISSR, RAPD and SRAP markers. Aust J Crop Sci. 2013;7(10):1463–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Darrah H. The cultivated basils. Independence: Thomas Buckeye Printing Company; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- De Masi L, Siviero P, Esposito C, Castaldo D, Siano F, Laratta B. Assessment of agronomic, chemical and genetic variability in common basil (O. basilicum) Eur Food Res Technol. 2006;223:273–281. doi: 10.1007/s00217-005-0201-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dikshit HK, Jhang T, Singh NK, Koundal KR, Bansal KC, Chandra N, Tickoo JL, Sharma TR. Genetic differentiation of Vigna species by RAPD, URP and SSR markers. Biol Plant. 2007;51(3):451–457. doi: 10.1007/s10535-007-0095-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JI. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta J, Lal N, Kaashyap M, Gupta PP (2010) Efficiency of three PCR based marker systems for detecting DNA polymorphism in Cicer arietinum L and Cajanus cajan L Millspaugh. Genet Eng Biotech J GEBJ 5

- Grativol C, Lira-Medeiros CF, Hemerly AS, Ferreira PCG. High efficiency and reliability of inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSR) markers for evaluation of genetic diversity in Brazilian cultivated Jatropha curcas L. accessions. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:4245–4256. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harisaranraj R, Prasitha R, Babu SS, Suresh K. Analysis of inter-species relationships of Ocimum species using RAPD markers. Ethnobot Leafl. 2008;12:609–613. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard P. Nouvelles recherches sur la distribution florale. Bull Soc Vaud Sci Nat. 1908;44:223–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kesari V, Sathyanarayana VM, Parida A, Rangan L (2010) Molecular marker-based characterization in candidate plus trees of Pongamia pinnata, a potential biodiesel legume. AoB Plants 1–12:plq017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lal S, Mistry K, Thaker R, Shah S, Vaidya P. Genetic diversity assessment in six medicinally important species of Ocimum from central Gujarat (India) utilizing RAPD, ISSR and SSR markers. Int J Adv Biol Res. 2012;2(2):279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Lalhruaitluanga H, Prasad MNV. Genetic diversity assessment in Melocanna baccifera Roxb. growing in Mizoram State of India—comparative results for RAPD and ISSR markers. Afr J Biotech. 2009;8(22):6053–6062. [Google Scholar]

- Mabberley DJ. A portable dictionary of the higher plants. Useful, dictionary of genera and families of angiosperms. J Calif Nativ Plant Soc. 1997;30(2):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 1967;27(2):209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka T, Ogihara Y. Applicability of inter-simple sequence repeat polymorphisms in wheat for use as DNA markers in comparison to RFLP and RAPD markers. Theor Appl Genet. 1997;94:597–602. doi: 10.1007/s001220050456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbi SR (1996) Nucleic acids II: The polymerase chain reaction. In: Hillis DM, Moritz C, Mable BK (eds) Molecular systematics, 2nd edn. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA, pp 205–247

- Powell W, Morgante M, Andre C, Hanafey M, Vogel J, Tingey S, Rafalski A. A comparison of RFLP, RAPD, AFLP and SSR markers for germplasm analysis. Mol Breed. 1996;2:225–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00564200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pushpangadan P, Bradu BL (1995) Basil, medicinal and aromatic plants. Advances in horticulture, vol 11. Malhotra Publishing House, New Delhi

- Pushpangadan P, Sobti S. Medicinal properties of Ocimum (Tulsi) species and some recent investigation of their efficacy. Indian Drugs. 1977;14(11):207–208. [Google Scholar]

- Raina AP, Kumar A, Dutta M (2013) Chemical characterization of aroma compounds in essential oil isolated from “Holy Basil” (Ocimum tenuiflorum L.) grown in India. Genet Res Crop Evol 60 (5):1727–1735

- Reddy P, Sarla N, Siddiq EA. Inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) polymorphism and its application in plant breeding. Euphytica. 2002;128:9–17. doi: 10.1023/A:1020691618797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf FJ (1998) NTSys-pc: numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system, version 2.02. Exter Software, Setauket

- Satovic Z, Liber Z, Karlovic K, Kolak I. Genetic relatedness among basil (Ocimum spp.) accessions using RAPD markers. Acta Biol Cracoviensia Bot. 2002;44:155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sikdar B, Bhattacharya M, Mukherjee A, Banerjee A, Ghosh E, Ghosh B, Roy SC. Genetic diversity in important members of Cucurbitaceae using isozyme, RAPD and ISSR markers. Biol Plant. 2010;54:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s10535-010-0021-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AP, Dwivedi S, Bharti S, Srivastava A, Singh V, Khanuja SPS. Phylogenetic relationships as in Ocimum revealed by RAPD markers. Euphytica. 2004;136:11–20. doi: 10.1023/B:EUPH.0000019497.89760.e8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V, Birendra V, Suvagiya V. A review on ethnomedical uses of Ocimum sanctum (tulsi) Int Res J Pharm. 2011;2(10):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Sobti SN, Pushpangadan P. Cytotaxonomical studies in the genus Ocimum. In: Bir SS, editor. Taxonomy, cytogenetics and cytotaxonomy of plants. Ludhiana: Kalyani Publication; 1979. pp. 373–377. [Google Scholar]

- Taran B, Zhang C, warkentin T, Tullu A, Vanderberg A. Genetic diversity among varieties and wild species accessions of pea (Pisum sativum L.) based on molecular markers, and morphological and physiological characters. Genome. 2005;48:257–272. doi: 10.1139/g04-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira RF, Goldsbrough P, Simon JE. Genetic diversity of basil (Ocimum spp.) based on RAPD markers. J Am Soc Hort Sci. 2003;128(1):94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wren RW. Potter’s new cyclopedia for botanical drugs and preparation. Rustington: Potter and Clarke, Ltd., Health Science Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Zhao Y, Chen DF, Chen JK, Zhao TS. ISSR primer screening and preliminary evaluation of genetic diversity in wild populations of Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Biol Plant. 2008;52:117–120. doi: 10.1007/s10535-008-0022-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz M, Ekbic E, Keles D, Sensoy S, Abak K. Use of ISSR, SRAP, and RAPD markers to assess genetic diversity in Turkish melons. Sci Hort. 2011;130:349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2011.06.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]