Abstract

Introduction

Inflammatory autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis) have a considerable impact on patients’ quality of life and healthcare budgets. Biosimilar infliximab (Remsima®) has been authorized by the European Medicines Agency for the management of inflammatory autoimmune diseases based on a data package demonstrating efficacy, safety, and quality comparable to the reference infliximab product (Remicade®). This analysis aims to estimate the 1-year budget impact of the introduction of Remsima in five European countries.

Methods

A budget impact model for the introduction of Remsima in Germany, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium was developed over a 1-year time horizon. Infliximab-naïve and switch patient groups were considered. Only direct drug costs were included. The model used the drug-acquisition cost of Remicade. The list price of Remsima was not known at the time of the analysis, and was assumed to be 10–30% less than that of Remicade. Key variables were tested in the sensitivity analysis.

Results

The annual cost savings resulting from the introduction of Remsima were projected to range from €2.89 million (Belgium, 10% discount) to €33.80 million (Germany, 30% discount). If any such savings made were used to treat additional patients with Remsima, 250 (Belgium, 10% discount) to 2602 (Germany, 30% discount) additional patients could be treated. The cumulative cost savings across the five included countries and the six licensed disease areas were projected to range from €25.79 million (10% discount) to €77.37 million (30% discount). Sensitivity analyses showed the number of patients treated with infliximab to be directly correlated with projected cost savings, with disease prevalence and patient weight having a smaller impact, and incidence the least impact.

Conclusion

The introduction of Remsima could lead to considerable drug cost-related savings across the six licensed disease areas in the five European countries.

Funding

Mundipharma International Ltd.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-015-0233-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ankylosing spondylitis, Biosimilar, Crohn’s disease, Infliximab, Psoriasis, Psoriatic arthritis, Remicade®, Remsima®, Rheumatoid arthritis, Ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis (UC), psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are inflammatory autoimmune diseases. These conditions are generally chronic and lifelong, characterized by alternating flare-ups and periods of remission. Given their chronic, and often progressive, nature, they have a considerable impact on patients’ quality of life [1–5] as well as healthcare budgets [6–10]. First-line treatments include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (cDMARDs; e.g., methotrexate), and topical and/or local corticosteroids; immunosuppressants and systemic corticosteroids are also used [11–16]. Inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) have shown good efficacy and an acceptable safety profile in patients after failure of conventional treatments, and in those patients with contraindications to conventional treatments [17–20]. TNF-α inhibitors are biologics, which are defined as medicines that are produced by cells (ranging from bacterial cells or yeast, to murine or human cell lines), or derived from a biological source.

Infliximab (Remicade®; Janssen Biotech, Inc.) was granted marketing authorization in 1999 [21]. It is a monoclonal antibody and TNF-α inhibitor, indicated in the areas of RA, AS, adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease, adult and pediatric UC, psoriasis, and PsA [21]. The efficacy and safety of infliximab in these disease areas is supported by extensive clinical evidence [16, 22–26]. Biosimilar infliximab (Remsima®; Celltrion, Inc.) is a biosimilar of Remicade. Biosimilars, in contrast to generics, do not have to be identical to the innovator and/or brand product. The intrinsic complexity of the molecule and their biological derivation means that it is not possible to produce exact copies of the reference product. Biosimilars must demonstrate similarity to the reference product in terms of quality, biological activity, clinical efficacy, and safety [27–29]. Remsima was authorized in 2013 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the same indications as the reference product Remicade [30]. Remsima was the first biosimilar antibody to meet the stringent EMA criteria for extrapolation of indications [31]. Remsima is supported by two clinical trials in patients with RA (PLANETRA; ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01217086) [32] and AS (PLANETAS; ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01220518) [33]. PLANETAS was a Phase I randomized, double-blind, multicenter, multinational, parallel-group study, designed to compare the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of Remsima and Remicade in 250 patients with AS [33]. PLANETRA was a Phase III, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, multinational, parallel-group study, designed to compare the efficacy and safety of Remsima and Remicade in 605 patients with RA and inadequate response to methotrexate treatment [32]. The pharmacokinetic profiles of Remsima and Remicade were demonstrated to be equivalent [30, 32, 33]. The trials also concluded that Remsima was well tolerated, with an efficacy and safety profile comparable to that of Remicade up to week 30 [30, 32, 33]. These 30-week results have been confirmed by 54-week data and 2-year follow-up extension studies [34–37].

Biologics, including TNF-α inhibitors, are costly compared with cDMARDs and have led to increased costs to healthcare systems [38]. Remicade has been the subject of several economic analyses (in different disease areas and countries) [39–44]. The results indicate that Remicade might be cost-effective in some patient groups, but appears unlikely to be cost-effective in others. Furthermore, even in cases where Remicade is cost-effective, any savings made are insufficient to offset the additional drug-acquisition and administration costs [45, 46] (see Appendix A for a nonsystematic literature review on the cost-effectiveness of Remicade).

Remsima is launching in the five European countries (Germany, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium) in 2015. The present budget impact analysis was designed to estimate the budget impact of the introduction of Remsima across the six licensed indications in these five European countries.

Methods

An Excel-based model was developed to estimate the budget impact of the introduction of Remsima for the treatment of RA, AS, Crohn’s disease, UC, psoriasis, or PsA, as per licensed indications in five European countries (Germany, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium).

Population

The population of interest comprised both an infliximab-naïve and a switch (patients currently treated with infliximab) patient population. Patient weight was assumed to be 75 kg [47]. In both populations, a fixed cohort of patients with the disease was analyzed over the 1-year time horizon of the model. The model applied a top-down epidemiological approach (i.e., using the incidence and/or prevalence as basis) to calculate the number of eligible patients who, under current prescribing practice, would be treated with infliximab in each population.

Population estimates for the included countries were obtained from the United Nations [48] (Table 1). Prevalence data applied in the model were sourced via a comprehensive literature search of the PubMed and Embase databases, and supplied by Kantar Health (Epi Database®. Kantar Health. Data on file). Incidence data for the treatment-naïve population were derived from the published literature, and country-specific data were applied if possible (Table 2). In the absence of country-specific incidence data, data were derived from other studies, and assumptions regarding the generalizability and appropriateness of these data were made (Table 2). It was assumed in the model that all patients present at the beginning of the forecast year, with costs reflecting treatment for a year. Selection of incidence and prevalence data was based upon the limited available published evidence. For consistency, where possible, prevalence rates were taken from the same source.

Table 1.

Model inputs: population numbers [48] and Remicade vial price (100 mg)

| Population 2015 | Remicade list price | |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | 82,562,000 | €753.48a |

| UK | 63,844,000 | £419.62a |

| Italy | 61,142,000 | €515.03a |

| The Netherlands | 16,844,000 | €602.43 [50] |

| Belgium | 11,183,000 | €524.00a |

aIHS Research, 2014, data on file

Table 2.

Model inputs: estimated annual prevalence and incidence rates (%); dose and annual number of doses of infliximab used

| % | RA | AS | CD | UC | Psoriasis | PsA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalencea/incidence | ||||||

| Germany | 1.13/0.035b | 0.09/0.007c | 0.13/0.005 [51] | 0.06/0.004 [52] | 2.28/0.120d | 0.69/0.104e |

| UK | 1.02/0.035b | 0.10/0.007c | 0.16/0.009 [51] | 0.22/0.012 [52] | 1.51/0.140 [53] | 0.11/0.017 [54] |

| Italy | 0.31/0.098 [55] | 0.09/0.007c | 0.09/0.002 [51] | 0.12/0.008 [52] | 1.15/0.230 [56] | 0.12/0.019e |

| The Netherlands | 1.02/0.035b | 0.09/0.007c | 0.12/0.007 [51] | 0.05/0.013 [52] | 2.14/0.120 [57] | 0.64/0.097e |

| Belgium | 1.07/0.035b | 0.09/0.007c | 0.12/0.004 [51] | 0.05/0.013h | 2.14/0.120d | 0.65/0.098e |

| Dose | 3 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg |

| No. of doses (switch) | 6.5 | 7.43 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| No. of doses (naïve)f | 8.75 | 9.57g | 8.75 | 8.75 | 8.75 | 8.75 |

Where a reference source gave a range, a mid-point estimate was used. Values shown have been rounded to the third decimal point

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, UC ulcerative colitis

aEpi Database®. Kantar Health. Data on file

bMusculoskeletal Health in Europe Report v5 [58]. A mean value of the range given (derived from published literature) was used

cTaken from [59], supported by [60]. The consistent data from two such different locations suggest that this incidence rate is likely to be consistent across North America and Europe

dThe incidence for Germany and the UK was assumed to be the same as for The Netherlands

eFor these countries, the incidence was calculated from the UK incidence, weighted based on the prevalence in the respective country

fIncluding one loading dose

gThe SPC indicated that maintenance doses should be administered every 6–8 weeks; therefore, 7 weeks was used for the purpose of this model

hData from The Netherlands were used as proxy

The percentages of patients treated with any medication (i.e., biological [b]DMARDs or cDMARDs) for their condition (termed ‘drug-treated patients’) are presented in Table 3. To these patients, the model applied the proportion of drug-treated patients who receive reference infliximab. The number of drug-treated patients and proportion of patients receiving infliximab (termed ‘patients currently treated with Remicade’) was applied to the cohort of switch and treatment-naïve patients. In the case of treatment-naïve patients, the purpose was to calculate under current prescribing practice the number of patients expected to be treated with infliximab.

Table 3.

Model inputs: estimate of percentage of patients treated with medication for their condition (drug-treated patients) and number of patients currently treated with infliximab (Remicade)

| % | RA | AS | CD | UC | Psoriasis | PsA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of drug-treated patientsa | ||||||

| Germany | 48.75 | 48.75b | 63.55 | 81.20 | 32.89 | 48.75b |

| UK | 48.75 | 48.75b | 54.70 | 77.20 | 63.17 | 48.75b |

| Italy | 48.75 | 48.75b | 46.44 | 81.70 | 44.52 | 48.75b |

| The Netherlands | 48.75 | 48.75b | 58.94 | 77.40 | 44.46 | 48.75b |

| Belgium | 48.75 | 48.75b | 58.94 | 77.40 | 44.46 | 48.75b |

| Number of patients currently treated with infliximab (Remicade)c | ||||||

| Germany | 1925 | 1278 | 11,719 | 3835 | 1065 | 1918 |

| UK | 3160 | 485 | 6417 | 988 | 568 | 455 |

| Italy | 1840 | 1562 | 2188 | 2499 | 1388 | 2188 |

| The Netherlands | 1070 | 464 | 4214 | 1593 | 103 | 196 |

| Belgium | 1152 | 537 | 3838 | 1535 | 230 | 384 |

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, UC ulcerative colitis

aPharmapoint Rheumatoid Arthritis Global Forecast 2013–2022. Data on file. Values for Netherlands and Belgium were taken from a Western Europe average of France, Germany and United Kingdom treatment data

bRA data used as proxy

cIMS 2013. Data on file

The number of patients calculated through this approach in the model received either Remicade or Remsima, according to the market uptake assumptions made.

Uptake of Remsima

The uptake of Remsima (expressed as the proportion of patients receiving Remsima who would otherwise have received Remicade) was estimated at 25% in the switch and 50% in the naïve populations. The difference in values was adopted to reflect that uptake is likely to be greater in treatment-naïve patients compared with patients who could potentially switch, because patients already receiving Remicade might be more likely to stay on their existing therapy compared with those initiating infliximab therapy. In our model, there was a linear relation between uptake and budget impact (i.e., doubling the uptake from 50% to 100% would double the budget impact). Therefore, the impact of changes in uptake could be easily inferred, but has not been investigated in a sensitivity analysis.

Costs

The country-specific list prices for Remicade used in the model are shown in Table 1. Remsima had not launched at the time of model development, and the exact local price of Remicade was not known, because biologics are often discounted at a local level. Therefore, this model was built with a range of discount scenarios (10–30%, assumption) compared with the current list price of Remicade.

Dosing was assumed to be the same for Remicade and Remsima, and was taken from the Remicade Summary of Product Characteristics [21] (Table 2). Treatment-naïve patients (but not switch patients) were assumed to receive a loading-dose phase. The loading dose was equivalent to the maintenance dose, except for a shorter time interval between loading doses than between subsequent maintenance doses. It was conservatively assumed that vials would be shared in the most-efficient manner. Only direct drug costs were considered in the model. All other costs (e.g., the cost of administration, monitoring, and adverse events) were assumed to be the same for Remicade and Remsima [30].

The analysis in this article was based on previously conducted studies, and did not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Model Structure and Equations

Patient Numbers

The total number of patients being treated with either Remsima or Remicade was defined as:

where is total number of patients (treated with either Remicade or Remsima); is number of patients treated with Remicade in the model; is number of patients treated with Remsima in the model.

The variables and were calculated as follows:

where is countries selected in the model; is indications selected in the model; is total population of indication in country ; for switch patient group: prevalence of indication in country , for treatment-naïve patient group: incidence of indication in country (Table 2); is proportion of patients treated with drugs for indication in country ; is proportion of drug-treated patients treated with Remsima indication in country .

For the purpose of this budget impact model, it was assumed that the total patients was constant in both scenarios (introducing Remsima or not introducing it), that is, patients switching to Remsima always did so from Remicade. This assumption was made to enable direct comparison of cost difference between the two scenarios.

Patient Costs

The total cost per patient was calculated as:

where = total cost per Remicade patient for indication in country ; is total cost per Remsima patient for indication in country ; is cost per 100-mg vial of Remicade in country ; is cost per 100-mg vial of Remsima in country ; is total number of vials required per patient per dose for indication ; for naïve patients: total number of doses required per year for indication : Table 2, calculated as: , where 3 represented the loading doses (i.e., the doses until maintenance intervals were established), for switch patients: total number of doses required per year for indication : calculated as:

The budget impact was calculated as:

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of results. Parameters varied in the sensitivity analysis included the number of patients treated with Remicade (±10%), prevalence estimates (±10%), incidence estimates (±10%), and patient’s weight (±5 kg). Parameters were varied for both the ‘switch’ and naïve population groups within the specified ranges for each of the indications of interest. The analyses were performed for each of the three discount scenarios.

Results

Assuming that Remsima would be available at a price that is between 10% and 30% less than that of Remicade, the annual drug cost savings that could be made through the introduction of Remsima across the six licensed disease areas were projected to range from €2.89 million in Belgium (10% discount scenario) to €33.80 million in Germany (30% discount scenario) (Table 4) (for infliximab-naïve and switch patients combined). The cumulative drug cost savings across the five countries included (Germany, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium) and the six licensed disease areas were projected to range from €25.79 million (10% discount) to €77.37 million (30% discount). Detailed projected drug cost savings by disease area and country are shown in Table 4. If such savings were made and used to treat additional patients with Remsima, the number of additional patients that could be treated across the six disease areas ranged from 250 in Belgium (10% discount scenario) to 2602 in Germany (30% discount scenario) (Table 5). Detailed results for estimated numbers of additional patients that could be treated with Remsima are shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Projected drug cost savings resulting from the introduction of Remsima during the first year after launch; combined for switch and naïve patient populations

| Million €a | RA | AS | CD | UC | PsA | Psoriasis | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% discount scenario | |||||||

| Germany | 0.575 | 0.811 | 5.969 | 2.112 | 1.241 | 0.558 | 11.266 |

| UK | 0.597 | 0.190 | 2.118 | 0.327 | 0.185 | 0.205 | 3.621 |

| Italy | 0.646 | 0.677 | 0.734 | 0.932 | 0.967 | 0.670 | 4.625 |

| The Netherlands | 0.257 | 0.235 | 1.784 | 0.967 | 0.101 | 0.044 | 3.389 |

| Belgium | 0.240 | 0.237 | 1.343 | 0.810 | 0.173 | 0.085 | 2.887 |

| Total | 2.315 | 2.150 | 11.949 | 5.148 | 2.667 | 1.561 | 25.789 |

| 20% discount scenario | |||||||

| Germany | 1.149 | 1.623 | 11.939 | 4.225 | 2.481 | 1.117 | 22.532 |

| UK | 1.194 | 0.380 | 4.235 | 0.654 | 0.370 | 0.409 | 7.242 |

| Italy | 1.291 | 1.355 | 1.469 | 1.863 | 1.935 | 1.339 | 9.252 |

| The Netherlands | 0.515 | 0.471 | 3.569 | 1.934 | 0.203 | 0.087 | 6.778 |

| Belgium | 0.480 | 0.474 | 2.686 | 1.621 | 0.345 | 0.169 | 5.775 |

| Total | 4.630 | 4.301 | 23.897 | 10.295 | 5.333 | 3.121 | 51.578 |

| 30% discount scenario | |||||||

| Germany | 1.724 | 2.432 | 17.908 | 6.337 | 3.722 | 1.675 | 33.798 |

| UK | 1.792 | 0.569 | 6.353 | 0.980 | 0.554 | 0.614 | 10.862 |

| Italy | 1.937 | 2.032 | 2.203 | 2.795 | 2.902 | 2.009 | 13.878 |

| The Netherlands | 0.772 | 0.706 | 5.353 | 2.900 | 0.304 | 0.131 | 10.167 |

| Belgium | 0.720 | 0.711 | 4.028 | 2.431 | 0.518 | 0.254 | 8.662 |

| Total | 6.944 | 6.451 | 35.846 | 15.443 | 8.000 | 4.682 | 77.367 |

Numbers have been rounded to the nearest 10,000

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, UC ulcerative colitis

aUK costs were converted to € using a conversion rate of 1.127278 (http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=SNA_TABLE4#)

Table 5.

Number of additional patients who could be treated with Remsima using the drug cost savings made during the first year after launch of Remsima; combined for switch and naïve patient populations

| RA | AS | CD | UC | PsA | Psoriasis | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% discount scenario | |||||||

| Germany | 57 | 41 | 352 | 122 | 69 | 33 | 674 |

| UK | 94 | 15 | 197 | 30 | 16 | 19 | 372 |

| Italy | 84 | 50 | 64 | 79 | 79 | 54 | 410 |

| The Netherlands | 32 | 15 | 130 | 66 | 7 | 3 | 253 |

| Belgium | 34 | 17 | 114 | 63 | 14 | 7 | 250 |

| Total | 300 | 139 | 858 | 361 | 186 | 116 | 1960 |

| 20% discount scenario | |||||||

| Germany | 128 | 93 | 792 | 275 | 156 | 74 | 1517 |

| UK | 211 | 35 | 444 | 69 | 37 | 42 | 838 |

| Italy | 189 | 113 | 144 | 178 | 178 | 121 | 924 |

| The Netherlands | 71 | 34 | 293 | 148 | 16 | 7 | 570 |

| Belgium | 77 | 39 | 257 | 142 | 31 | 16 | 562 |

| Total | 676 | 313 | 1,930 | 812 | 419 | 260 | 4410 |

| 30% discount scenario | |||||||

| Germany | 219 | 159 | 1358 | 472 | 268 | 126 | 2602 |

| UK | 362 | 60 | 762 | 117 | 64 | 72 | 1436 |

| Italy | 324 | 195 | 247 | 305 | 306 | 208 | 1583 |

| The Netherlands | 122 | 58 | 503 | 253 | 27 | 12 | 976 |

| Belgium | 132 | 67 | 440 | 244 | 54 | 27 | 964 |

| Total | 1158 | 538 | 3309 | 1392 | 718 | 446 | 7561 |

Numbers of patients have been rounded to the nearest integer

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, UC ulcerative colitis

Sensitivity Analyses

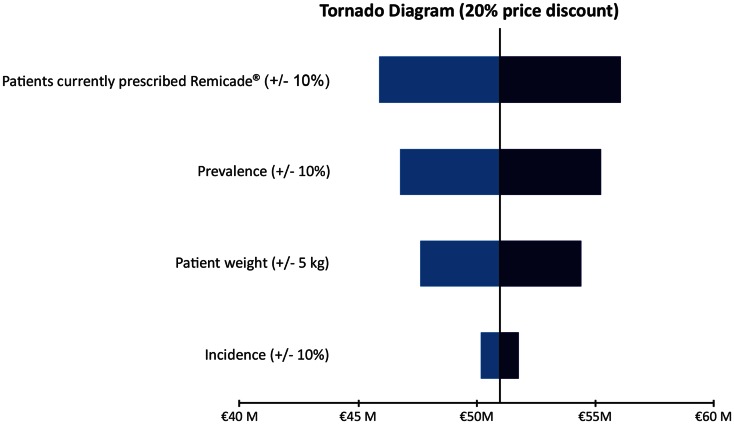

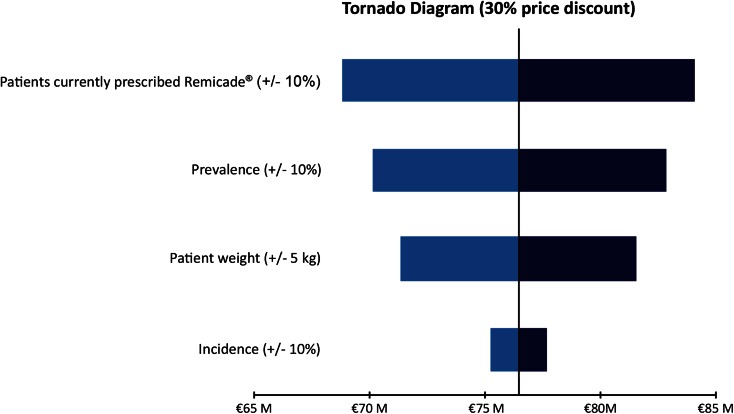

Tornado diagrams for the one-way sensitivity analyses are shown in Fig. 1 (for the 10% discount scenario), Fig. 2 (for the 20% discount scenario), and Fig. 3 (for the 30% discount scenario). As would be expected, any changes have the lowest impact in the 10% discount scenario and the highest impact in the 30% discount scenario. Of the four parameters explored in the sensitivity analysis, the percentage of patients treated with Remicade (i.e., the total number of patients considered in the model) had the biggest impact, because an increase or decrease in this parameter would translate directly and linearly into the projected savings (i.e., a 10% increase in patients being treated with Remicade or Remsima led to a 10% increase in projected savings, if all other model parameters remained unchanged). The impact of a change in prevalence was slightly lower, with a 10% change leading to a corresponding 8.4% change in projected savings. Changing patient weight by 5 kg led to a change in projected savings of 6.7%. A 10% change in disease incidence had the smallest impact, with only a 1.6% change in projected savings.

Fig. 1.

Sensitivity analyses of projected drug cost savings resulting from the introduction of Remsima; 10% discount scenario. M million

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity analyses of projected drug cost savings resulting from the introduction of Remsima; 20% discount scenario. M million

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity analyses of projected drug cost savings due to the introduction of Remsima; 30% discount scenario. M million

Discussion

We developed a budget impact model for the introduction of Remsima in five European countries over a 1-year time horizon. The list price of Remsima was not known at the time of this analysis. This budget impact model was based on the assumption that the list price of Remsima might be between 10% and 30% lower than the current list price of Remicade. Our model showed that the introduction of Remsima under those circumstances was highly likely to be associated with considerable drug cost savings for the healthcare payer. Our model found the price of Remsima to be the main driver of budget impact (as demonstrated by the different price-discount scenarios). The number of patients currently treated with Remicade was found to have a considerable, but less important, directly correlating effect on the projected savings. Changes in prevalence and patient weight had slightly less impact on projected savings. Changes in incidence were found to lead to the lowest changes in budget impact (among the variables explored).

The analysis is limited by the fact that the final launch price of Remsima and local discounts of Remsima and Remicade, which our model showed to be the main determinant of the budget impact, is not yet known. We also emphasize the importance of local price negotiations, which might have a significant effect on the budget impact. Furthermore, this analysis assumed the same administration and monitoring cost for Remsima and Remicade and the model did not take patient mortality into account, which introduces a slight bias that might overstate the budget impact of Remsima.

Since the development of our model, Remsima has launched in the five countries included in the analysis. Based on the 2015 list prices of Remsima and Remicade, the introduction of Remsima would lead to budget savings of €45.13 million and 3900 additional patients could be treated with Remsima across the five countries included. Appendix B provides the results of this additional analysis (Appendix B). However, the range of price discounts in the main analysis remains valid, given the uncertainty around local discounts provided for both therapies and possible price changes. Therefore, these results need to be interpreted with caution.

The results of our budget impact model strongly suggested that, if decision makers facilitated access to Remsima, potential drug cost savings could be made. Furthermore, there are indicators (based on UK data collected in 2006) that, because of the high drug-acquisition cost, not all patients who could benefit from anti-TNF therapy have access to it [49]. If this is the case, our analysis showed that there is the potential for additional patients to be treated with Remsima.

Conclusion

The introduction of Remsima could lead to drug cost-related savings across Germany, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium. A less-costly brand of infliximab might also lead to wider patient access and, therefore, improved patient outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship for this study and article-processing charges, as well as the open access fee, were funded by Mundipharma International Ltd, Cambridge, UK, which also commissioned and funded the study. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. The manuscript was prepared by Brigitte Moore, of Abacus International, and funded by Mundipharma International Ld, Cambridge, UK.

Conflict of interest

Ashok Jha and Will Dunlop are employees of Mundipharma International Ltd, Cambridge, UK. Alex Upton is an employee of Abacus International, Bicester, UK, which was contracted by Mundipharma International Ltd. Ron Akehurst has previously received fees from Mundipharma International Ltd for consulting services.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The analysis in this article was based on previously conducted studies, and did not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

References

- 1.Uhlig T, Loge JH, Kristiansen IS, Kvien TK. Quantification of reduced health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared to the general population. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1241–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boonen A, Mau W. The economic burden of disease: comparison between rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(Suppl 55):S112–S117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordin K, Pahlman L, Larsson K, Sundberg-Hjelm M, Loof L. Health-related quality of life and psychological distress in a population-based sample of Swedish patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:450–457. doi: 10.1080/003655202317316097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–407. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70112-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen CF, Mussani F, Chandran V, et al. Patients with psoriatic arthritis have worse quality of life than those with psoriasis alone. Rheumatol (Oxf) 2012;51:571–576. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundkvist J, Kastang F, Kobelt G. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis and access to treatment: health burden and costs. Eur J Health Econ. 2008;8(Suppl. 2):S49–S60. doi: 10.1007/s10198-007-0088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franke LC, Ament AJ, van de Laar MA, Boonen A, Severens JL. Cost-of-illness of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(Suppl. 55):S118–S123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan J, Wordsworth S, Ahmad T, et al. Managing the long term care of inflammatory bowel disease patients: the cost to European health care providers. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:301–316. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonia A, Jackson K, Lereun C, et al. A retrospective cohort study of the impact of biologic therapy initiation on medical resource use and costs in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:807–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy M, Papneja A, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Gladman DD. Prevalence and predictors of reduced work productivity in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:342–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492–509. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X, et al. 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:896–904. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.151027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28–62. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:991–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. CG153: Psoriasis: the assessment and management of psoriasis. 2012. http://publications.nice.org.uk/psoriasis-cg153. Accessed 02 Feb 2015. [PubMed]

- 16.Gossec L, Smolen JS, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:4–12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobelt G, Eberhardt K, Geborek P. TNF inhibitors in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice: costs and outcomes in a follow up study of patients with RA treated with etanercept or infliximab in southern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:4–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.010629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machado MA, Barbosa MM, Almeida AM, et al. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with TNF blockers: a meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:2199–2213. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2772-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen OH, Ainsworth MA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:754–762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yost J, Gudjonsson JE. The role of TNF inhibitors in psoriasis therapy: new implications for associated comorbidities. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:30. doi: 10.3410/M1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merck Sharp and Dohme Ltd. Remicade. Summary of product information. http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/3236/SPC/Remicade+100mg+powder+for+concentrate+for+solution+for+infusion/. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 22.Blumenauer B, Judd M, Wells G, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;CD003785. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003785/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Toussirot E, Bertolini E, Wendling D. Management of ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab. Open Access Rheumatol Res Rev. 2009;1:69–82. doi: 10.2147/OARRR.S4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawalec P, Mikrut A, Wisniewska N, Pilc A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibodies (infliximab, adalimumab and certolizumab) in Crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:765–779. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.38670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawson MM, Thomas AG, Akobeng AK. Tumour necrosis factor alpha blocking agents for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD005112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005112.pub2/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Mustafa A, Al-Hoqail I. Biologic systemic therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a review. J Taibah Uni Med Sci. 2013;8:142–150. [Google Scholar]

- 27.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: non-clinical and clinical issues. 2006. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003920.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 28.European Medicines Agency. Questions and answers on biosimilar medicines (similar biological medicinal products). 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Medicine_QA/2009/12/WC500020062.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 29.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA issues draft guidance on biosimilar product development. 2012. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm291232.htm. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 30.European Medicines Agency. Remsima: European Public Assessment Report—summary for the public. 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002576/human_med_001682.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 31.European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency recommends approval of first two monoclonal-antibody biosimilars. Press release. 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2013/06/news_detail_001837.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 32.Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1613–1620. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1605–1612. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park W, Jaworski J, Brzezicki J, et al. A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase I study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy of CT-P13 and infliximab in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: 54-week results from the PLANETAS study. Poster presented at EULAR 2013b, Madrid, 12–15 June.

- 35.Park W, Miranda P, Brzosko M, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (infliximab biosimilar) over two years in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: comparison between continuing with CT-P13 and switching from infliximab to CT-P13. Poster #L15 presented at the ACR/ARHP 2013 Annual Meeting, Oct 2013, San Diego, 2013c.

- 36.Yoo DH, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (infliximab biosimilar) over two years in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between continued CT-P13 and switching from infliximab to CT-P13. Poster #L1 presented at the ACR/ARHP 2013 Annual Meeting, Oct 2013, San Diego, 2013c.

- 37.Yoo DH, Racewicz A, Brzezicki J, et al. A Phase III, randomised controlled trial to compare CT-P13 with infliximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: 54-week results from the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(Suppl. 3):A73. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huscher D, Mittendorf T, von Hinuber U, et al. Evolution of cost structures in rheumatoid arthritis over the past decade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:738–745. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gissel C, Repp H. Cost per responder of TNF-alpha therapies in Germany. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1805–1809. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2332-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobelt G, Andlin-Sobocki P, Brophy S, et al. The burden of ankylosing spondylitis and the cost-effectiveness of treatment with infliximab (Remicade) Rheumatol (Oxf) 2004;43:1158–1166. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Adalimumab for treatment of Crohn’s disease in Germany. 15th Annual European Conference of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research: abstract. PGI20, 3 Nov 2012.

- 42.Chaudhary MA, Fan T. Cost-Effectiveness of infliximab for the treatment of acute exacerbations of ulcerative colitis in the Netherlands. Biol Ther. 2013;3:45–60. doi: 10.1007/s13554-012-0007-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Portu S, Del Giglio M, Altomare G, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of TNF-alpha blockers for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis in the perspective of the Italian health-care system. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(Suppl. 1):S7–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cummins E, Asseburg C, Punekar YS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of infliximab for the treatment of active and progressive psoriatic arthritis. Value Health. 2011;14:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobelt G, Jonsson L, Young A, Eberhardt K. The cost-effectiveness of infliximab (Remicade) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden and the United Kingdom based on the ATTRACT study. Rheumatol (Oxf. 2003;42:326–335. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olivieri I, de Portu S, Salvarani C, et al. The psoriatic arthritis cost evaluation study: a cost-of-illness study on tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis patients with inadequate response to conventional therapy. Rheumatol (Oxf) 2008;47:1664–1670. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brodszky V, Baji P, Balogh O, Pentek M. Budget impact analysis of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in six Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(Suppl. 1):S65–S71. doi: 10.1007/s10198-014-0595-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population division, population estimates and projections section. 2012. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/unpp/panel_population.htm. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 49.Kay LJ, Griffiths ID, BSR Biologics Register Management Committee UK consultant rheumatologists’ access to biological agents and views on the BSR Biologics Register. Rheumatol (Oxf) 2006;45:1376–1379. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Z-Index B.V. 2014. https://www.z-index.nl/. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 51.Economou M, Zambeli E, Michopoulos S. Incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and its etiological influences. Ann Gastroenterol. 2009;22:158–167. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, et al. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD) Gut. 1996;39:690–697. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.5.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huerta C, Rivero E, Rodriguez LA. Incidence and risk factors for psoriasis in the general population. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1559–1565. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Insitute for Health and Care Excellence. Costing statement: Golimumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. 2012. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta220/resources/ta220-psoriatic-arthritis-golimumab-costing-statement2. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 55.Benucci M, Cammelli E, Manfredi M, et al. Early rheumatoid arthritis in Italy: study of incidence based on a two-level strategy in a sub-area of Florence (Scandicci-Le Signe) Rheumatol Int. 2008;28:777–781. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vena GA, Altomare G, Ayala F, et al. Incidence of psoriasis and association with comorbidities in Italy: a 5-year observational study from a national primary care database. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:593–598. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donker GA, Foets M, Spreeuwenberg P, van der Werf GT. Management of psoriasis in family practice is now in closer agreement with the guidelines of the Netherlands Society of Family Physicians. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1998;142:1379–1383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.EUMUSC. Musculoskeletal Health in Europe. Report v5.0. http://www.eumusc.net/myUploadData/files/Musculoskeletal%20Health%20in%20Europe%20Report%20v5.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2015.

- 59.Carbone LD, Cooper C, Michet CJ, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935–1989. Is the epidemiology changing? Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1476–1482. doi: 10.1002/art.1780351211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bakland G, Nossent HC, Gran JT. Incidence and prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in Northern Norway. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:850–855. doi: 10.1002/art.21577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.