Abstract

Objective: Professional antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DCs) and cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells, components of anti-cancer therapy, have shown clinical benefits and potential to overcome chemotherapeutic resistance. To evaluate whether DC-CIK cell-based therapy improves the clinical efficacy of chemotherapy, we reviewed the literature on DC-CIK cells and meta-analyzed randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Methods: We searched several databases and selected studies using predefined criteria. RCTs that applied chemotherapy with and without DC-CIK cells separately in two groups were included. Odds ratio (OR) and mean difference (MD) were reported to measure the pooled effect. Results: Twelve reported RCTs (826 patients), which were all performed on Chinese patients, were included. Combination therapy exhibited better data than chemotherapy: 1-year overall survival (OS) (OR=0.22, P<0.01), 2-year OS (OR=0.28, P<0.01), 3-year OS (OR=0.41, P<0.01), 1-year disease-free survival (DFS) (OR=0.16, P<0.05), 3-year DFS (OR=0.32, P<0.01), objective response rate (ORR) (OR=0.54, P<0.01), and disease control rate (DCR) (OR=0.46, P<0.01). Moreover, the levels of CD3+ T-lymphocytes (MD=−11.65, P<0.05) and CD4+ T-lymphocytes (MD=−8.18, P<0.01) of the combination group were higher. Conclusions: Immunotherapy of DC-CIK cells may enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy on solid cancer and induces no specific side effect. Further RCTs with no publishing bias should be designed to confirm the immunotherapeutic effects of DC-CIK cells.

Keywords: Solid carcinoma, Meta-analysis, Dendritic cells, Cytokine-induced killer cells, Immunotherapy

1. Introduction

Patients of malignant cancer often suffer from the adverse effects of common therapies (surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy). These treatments extend survival time, but may result in low quality-of-life. Small remnant lesions in situ and metastatic cancer cells are the main reasons for recurrence. Immunotherapy, using various methods to restore and enhance the immune abilities of patients to eliminate cancer cells, is an alternative and promising option in treating cancers (Liu et al., 2009). Immunotherapy overcomes immunosuppression induced by cancer, surgery, or chemotherapeutic agents (Shi et al., 2012). Diverse immunologic cells have been used in immunotherapy (Niu et al., 2011).

Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells, considered as the most cytotoxic immunologic effector cells, originate in vitro after being incubated with lymphocytes with CD3 monoclonal antibody (CD3McAb), interleukin (IL), and interferon (IFN) (Linn et al., 2002). Schmidt-Wolf et al. (1991) reported the anti-cancer potential of CIK cells and confirmed that CIK cells suppress the tumor burden and prolong survival of the murine severe combined immune deficiency (SCID)/human lymphoma models for the first time. Clinical studies have shown high efficiency, low toxicity (Liu et al., 2012), and prolonged overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) after CIK treatment (Hao et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2010).

Dendritic cells (DCs) can process and present antigens to T-lymphocytes. Different kinds of DC-vaccines have shown anti-tumor effects (Palucka et al., 2010; Baek et al., 2012). The innate quality of DCs in antigen presenting could effectively counteract the specificity deficiency and enhance the cytotoxicity of CIK cells. A rising number of studies (Thanendrarajan et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014a; Zhong et al., 2014) on the combination of active and passive immunotherapy have shown improved anti-tumor immune responses.

Synergistic use of CIK cells and docetaxel demonstrated a stronger anti-tumor effect in several multidrug-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (Liu et al., 2009). The property of antagonistic drug resistance of DC-CIK cells makes it appropriate for improving the clinical outcome of chemotherapy.

However, there is still no consensus on the utility of DC-CIK cells against solid cancers because of the lack of large-sample clinical trials. Accordingly, we meta-analyzed clinical randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and evaluated whether the DC-CIK therapy enhances anti-tumor activity and optimizes clinical outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search

We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, SinoMed, and ClinicalTrials.gov, using the keywords “cytokine-induced-killer” and “cancer” in English and Chinese languages. Free-text search was also performed. We also requested more clinical information by contacting drug manufacturers.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The main criteria for study inclusion were as follows: (1) RCTs, (2) the two arms in the study were chemotherapy and DC-CIK combined with chemotherapy, and (3) patients included were histologically confirmed as having solid cancer.

Main criteria for study exclusion were as follows: (1) phase I clinical study, (2) cohort studies, (3) retrospective study, (4) hematological cancer, or (5) use of DCs or CIK cells as simple regimen of immunotherapy.

2.3. Data extraction

Two reviewers extracted data independently. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Data extracted are as follows: name of author, year of publication, number of patients, type of cancer, median age, treatment duration, median follow-up, median DFS, median OS, complete response (CR), partial response (PR), and stable disease (SD).

2.4. Definition of outcome measurement

The primary endpoint in the analysis was OS. Other endpoints were DFS, disease control rate (DCR: CR+PR+SD), and objective response rate (ORR: CR+PR).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Cochrane Collaboration’s tool was applied to judge risk of bias, containing seven items. Statistical analysis was performed mainly by comparison of two arms of therapy using Review Manager 5.0 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Cochrane’s Q-test and I 2 (the corresponding quantity) demonstrated statistical heterogeneity among studies, and helped us choose an appropriate analysis model (fixed-effect model or random-effect model), with the significance threshold predefined as 0.1. For dichotomous variables (OS, DFS, DCR, and ORR), we calculated the pooled odds ratio (OR) of studies with the statistical method of Mantel-Haenszel to reflect the clinical effect of treatment, and pooled OR of <1 indicated that the combination therapy showed the preferred outcome. For continuous variables (number of T-lymphocyte subtypes), we calculated the mean difference (MD) of two arms of therapy. STATA 12.0 (STATA Co., College Station, TX, USA) was also applied for analysis. P-values of <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of studies

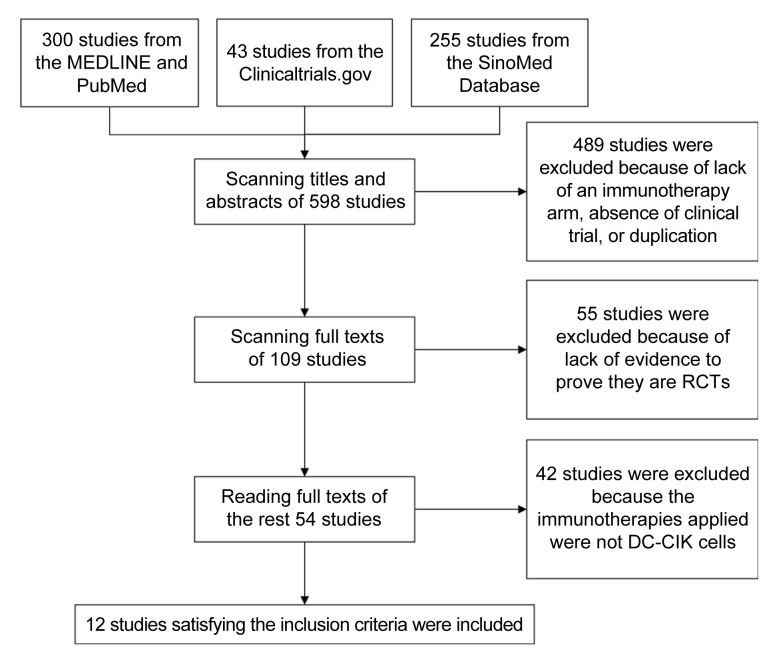

Five hundreds and ninety-eight studies, including 300 from MEDLINE and PubMed, 43 registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, and 255 from SinoMed, were analyzed initially. Of these, 489 were excluded because of lack of an immunotherapy arm, absence of clinical trial, or duplication. Fifty-five studies were excluded because of lack of evidence to prove that they are RCTs, leaving 26 articles in English and 28 articles in Chinese. Finally, 12 RCTs that used chemotherapy with and without DC-CIK separately as two arms were included (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection process

3.2. Quality assessment

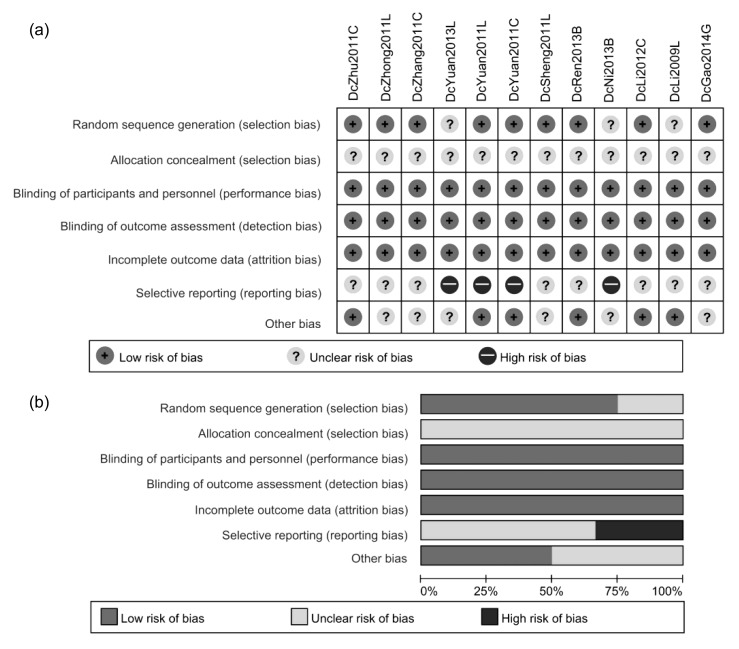

Random sequence generation of nine studies were judged as low risk and the remaining three studies lacked relevant depiction. However, allocation concealment was not feasible owing to the difference of treatment procedures between groups and was not described in sufficient detail in all studies. Risks of blinding and incomplete outcome data were low. Eight studies were of unclear risk in terms of selective reporting, and the other four studies were considered at high risk because of the lack of primary outcome data (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Results of quality assessment of included studies

(a) Risk of bias in each study. (b) Overall result of each item in quality assessment. DcZhu2011C, DcZhong2011L, DcZhang2011C, DcYuan2013L, DcYuan2011L, DcYuan2011C, DcSheng2011L, DcRen2013B, DcNi2013B, DcLi2012C, DcLi2009L, and DcGao2014G represent the studies as shown in Table 1

3.3. Patients’ characteristics of included trials

Twelve RCTs, available as published articles including 826 patients in total, were included. Distribution of gender and the median age of patients between groups had no significant differences. Table 1 summarizes the therapeutic regimens and other characteristics of included patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included patients

| Study ID | Cancer type | Receiving surgery previously | Chemo group |

Combination group |

||||

| Regimen | Number of patients/males | Median age (year) | Regimen | Number of patients/males | Median age (year) | |||

| DcLi2009L (Li et al., 2009) | NSCLC | Yes | Navelbine+cisplatin | 42/28 | 60.5 | DC-CIK+cisplatin+navelbine | 42/28 | 61 |

| DcZhong2011L (Zhong et al., 2011) | NSCLC | No | NP | 14/7 | DC-CIK+NP (vinorelbine with platinum) | 14/6 | ||

| DcYuan2011L (Yuan et al., 2011a) | NSCLC | No | Chemotherapy (unclear) | 32/20 | 66 | DC-CIK+chemotherapy (unclear) | 32/22 | 67.5 |

| DcSheng2011L (Sheng et al., 2011) | NSCLC | No | NP | 33 | DC-CIK+NP | 32 | ||

| DcZhang2011C (Zhang et al., 2011) | Rectal cancer | No | FOLFOX/FOLFIRI | 31 | DC-CIK+FOLFOX/FOLFIRI | 32 | ||

| DcYuan2011C (Yuan et al., 2011b) | Colorectal cancer | No | Chemotherapy (unclear) | 21/16 | 58 | DC-CIK+chemotherapy (unclear) | 21/15 | 60 |

| DcZhu2011C (Zhu et al., 2011) | Colorectal cancer | No | CF+5-Fu | 43/27 | 58.3 | DC-CIK+CF+5-Fu | 40/24 | 59.2 |

| DcLi2012C (Li et al., 2012) | Colon cancer | No | Oxaliplatin+CF+5-Fu | 20/15 | 57.5 | DC-CIK+CF+5-Fu+oxaliplatin | 20/13 | 54.5 |

| DcRen2013B (Ren et al., 2013) | Breast cancer | No | SDC | 79 | 52 | DC-CIK+HDC | 87 | 50 |

| DcYuan2013L (Yuan et al., 2013) | NSCLC | No | Platinum-based doublet chemotherapy | 44 | DC-CIK+Platinum-based doublet chemotherapy | 31 | ||

| DcNi2013B (Ni et al., 2013) | Breast cancer | Yes | AT | 26 | 51 | DC-CIK+AT | 36 | 49 |

| DcGao2014G (Gao et al., 2014) | Gastric/colorectal cancer | Yes | Chemotherapy (unclear) | 27/16 | 64.48 | DC-CIK+chemotherapy (unclear) | 27/16 | 61.56 |

NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; NP: vinorelbine and platinum; FOLFOX: 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin/oxaliplatin; FOLFIRI: 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin/irinotecan; CF: calcium folinate; 5-Fu: 5F-dUMP; SDC: standard-dose chemotherapy; HDC: high-dose chemotherapy; AT: docetaxel and doxorubicin

3.4. Characteristics of DC-CIK cell therapy

In all studies, autologous mononuclear cells were collected from patients and cultivated in medium. Adherent cells were then cultured with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-4, and autologous tumor antigen, and finally the DCs were harvested. Suspension cells were cultured in a medium containing IFN-γ, CD3McAb, and IL, transforming to CIK cells. Table 2 summarizes details of culture and regimens of DC-CIK cells.

Table 2.

Characteristics of DC-CIK cell therapy

| Study ID | DC-CIK cell regimen | Culture of CIK cells | Culture of DC cells |

| DcLi2009L (Li et al., 2009) | Two times of (13.07±1.37)×109 cells at 1-d intervals | CD3McAb, IL-1α, IFN-γ, IL-2 | GM-CSF, autologous tumor lysate |

| DcZhong2011L (Zhong et al., 2011) | (8.1±2.5)×106 DC cells and (13.3±3.5)×108 CIK cells | IFN-γ, CD3-Ab, IL-2 | GM-CSF, IL-4, CEA peptide |

| DcYuan2011L (Yuan et al., 2011a) | Four times of DC-CIK cell transfusion | Unclear | Unclear |

| DcSheng2011L (Sheng et al., 2011) | Two courses of 5×109 cells for four times | IFN-γ, CD3McAb, IL-1α, IL-2 | GM-CSF, IL-4, TNF-α |

| DcZhang2011C (Zhang et al., 2011) | Three times of cells >1×107 L−1 | IFN-γ, IL-2, CD3McAb, IL-1 | GM-CSF, IL-4, autologous tumor Ag, TNF-2α |

| DcYuan2011C (Yuan et al., 2011b) | DC cells >106 ml−1 and CIK cells >1010 ml−1 | IFN-γ, CD3McAb, IL-1α, IL-2 | GM-CSF, IL-4, IFN-γ, TNF-2α |

| DcZhu2011C (Zhu et al., 2011) | 5×105 U/L CIK cells and (3–7)×107 DC cells | IFN-γ, CD3McAb, IL-2 | IFN-γ, LPS |

| DcLi2012C (Li et al., 2012) | Two courses of transfusion on the 14, 15, 16 d of cell culture | IFN-γ, CD3McAb, IL-2 | GM-CSF, IL-4, IFN-γ |

| DcRen2013B (Ren et al., 2013) | Transfusion at every 4 d interval for three cycles starting 1 week before chemotherapy | IFN-γ, CD3, IL-2 | GM-CSF, IL-4, TNF-α |

| DcYuan2013L (Yuan et al., 2013) | 1010 cells transfused 7 d after the lastchemotherapy and continued for 4 d | IL-2, CD3McAb, phytohemagglutinin, IFN-γ | GM-CSF |

| DcNi2013B (Ni et al., 2013) | Six times of transfusion from the 7th day of cell culture | IFN-γ, CD3McAb, IL-2 | GM-CSF, IL-4, autologous tumor Ag, TNF-α |

| DcGao2014G (Gao et al., 2014) | Two cycles repeated 3 to 5 times in 2 weeks, from the 2nd or 3th day after chemotherapy | IFN-γ, CD3McAb, IL-2, gentamycin | GM-CSF, IL-4, autologous tumor Ag |

GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; CD3McAb: CD3 monoclonal antibody; CEA: carcino-embryonic antigen; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; IFN: interferon; IL: interleukin; Ag: antigen

3.5. Efficacy assessments

3.5.1. Overall survival

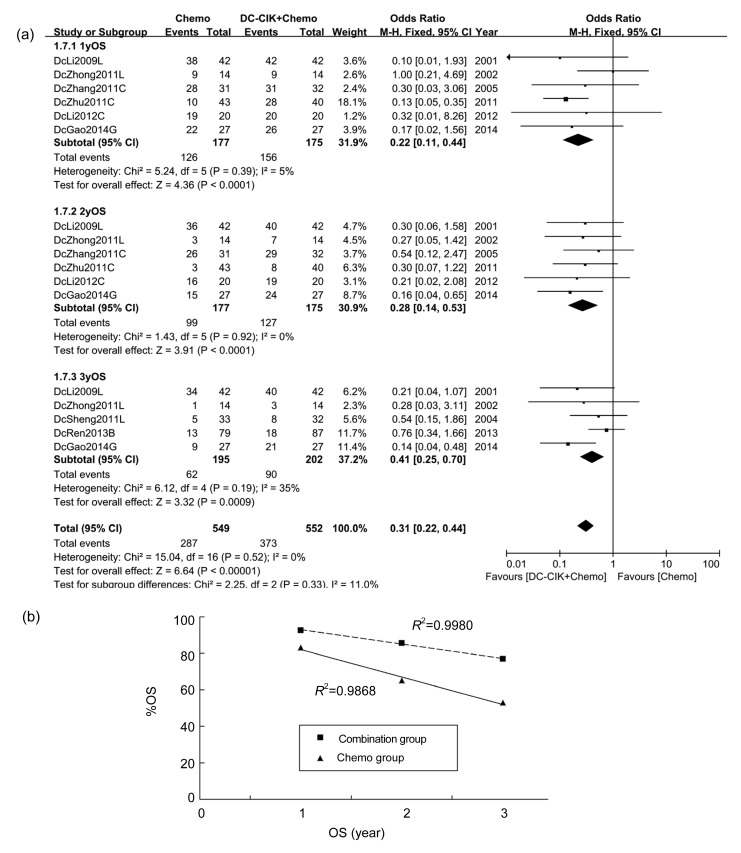

Six studies, which included 352 patients, reported 1-year OS. The 1-year OS rates in the chemo group (in which patients received chemotherapy only) and the combination group (in which patients received a combination of DC-CIK cells and chemotherapy) were 71.19% and 89.14%, respectively. OR in only one study (DcZhu2011C; Fig. 3a) showed statistical significance independently, but when the studies were integrated, the general OR was 0.22 (P<0.0001), indicating a significantly better 1-year OS in the combination group than in the chemo group (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

OS of patients in included studies

(a) Comparison of OS across groups. (b) Mean OS of three studies (DcLi2009L, DcZhong2011L, and DcGao2014G)

Information on 2-year OS was analyzed from six studies, which covered 352 patients. The 2-year OS rates in the chemo group and the combination group were 55.93% and 72.57%, respectively. All studies showed a longer 2-year OS in the combination group than in chemo group, among which only one (DcGao2014G; Fig. 3a) exhibited statistical significance. OR of 0.28 (P<0.0001) indicated that the general 2-year OS in the combination group was significantly longer compared with the chemo group (Fig. 3a).

Three-year OS, which was available in five studies including 397 patients, was 31.79% in the chemo group and 44.55% in the combination group. All five studies exhibited prolonged 3-year OS, among which one (DcGao2014G; Fig. 3a) showed statistical significance independently. OR was 0.41 (P=0.0009), suggesting overall 3-year OS in the combination group was significantly longer than that in the chemo group (Fig. 3a).

Three studies (DcLi2009L, DcZhong2011L, and DcGao2014G; Fig. 3a) reported 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS. The average %OS of the 3 years was calculated and shown using scatter plots with linear trend lines of each group (R 2=0.9868 in the chemo group; R 2=0.9980 in the combination group). Average %OS in the chemo group was 83.13%, 65.05%, and 53.01%, respectively, while %OS in the combination group was 92.77%, 85.54%, and 77.11%, respectively (Fig. 3b).

3.5.2. Disease-free survival

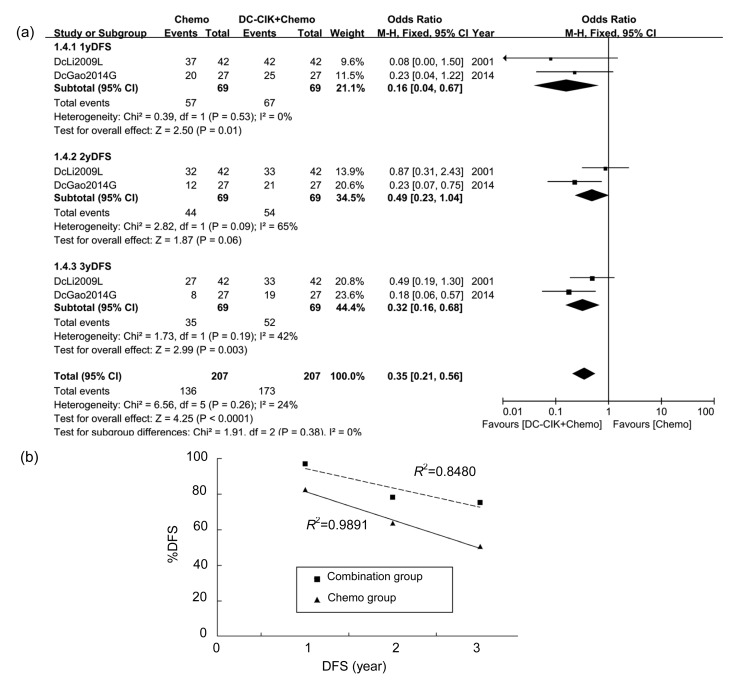

One-year DFS, which was available in only two studies including 138 patients, was 82.61% in the chemo group and 97.10% in the combination group. All studies exhibited prolonged 1-year DFS and OR was 0.16 (P=0.01), indicating that the overall 1-year DFS in the combination group was significantly better. A fixed-effect analysis model was used (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

DFS of patients in included studies

(a) Comparison of DFS across groups. (b) Mean DFS of two studies (DcLi2009L and DcGao2014G)

Information of 2-year DFS also came from two studies. The 2-year DFS rates in the chemo group and the combination group were 63.77% and 78.26%, respectively. All studies showed longer 2-year DFS in the combination group than in the chemo group. Overall OR of 0.49 (P=0.06) indicated no significant difference between groups (Fig. 4a).

Three-year DFS was 50.72% and 75.36% in the chemo group and the combination group, respectively. OR in only one study (DcGao2014G, Fig. 4a) showed independent statistical significance, but when the studies were integrated, the general OR was 0.32 (P=0.003), showing a significantly better 3-year DFS in the combination group than in the chemo group (Fig. 4a).

Two studies (DcLi2009L and DcGao2014G; Fig. 4a) reported 1-, 2-, and 3-year DFS at the same time. The average %DFS of 3 years was shown using scatter plots combining linear trend lines of each group (R 2=0.9891 in the chemo group; R 2=0.8480 in the combination group; Fig. 4b).

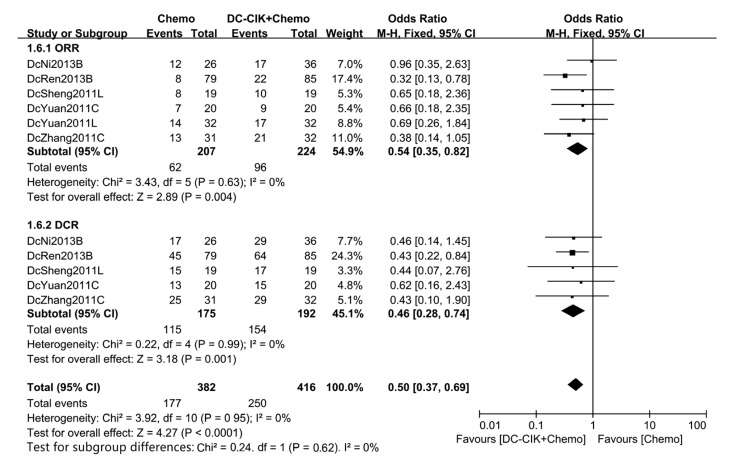

3.5.3. ORR and DCR

Six studies, covering 431 patients, reported CR and PR at the same time, and the ORR was 29.95% in the chemo group and 42.86% in the combination group. OR in all six studies showed better ORR and only one study (Ren et al., 2013) showed statistical significance, and an overall OR of 0.54 (P=0.004) implied that DC-CIK cells significantly raise ORR. A fixed-effect analysis model was used (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

ORR and DCR of patients in included studies

DCR, which was available in five studies including 367 patients, was 65.71% in the chemo group and 80.21% in the combination group. All five studies exhibited better DCR, of which one (Ren et al., 2013) showed statistical significance. Pooled OR was 0.46 (P=0.001), indicating that DCR in the combination group was significantly better than that in the chemo group (Fig. 5).

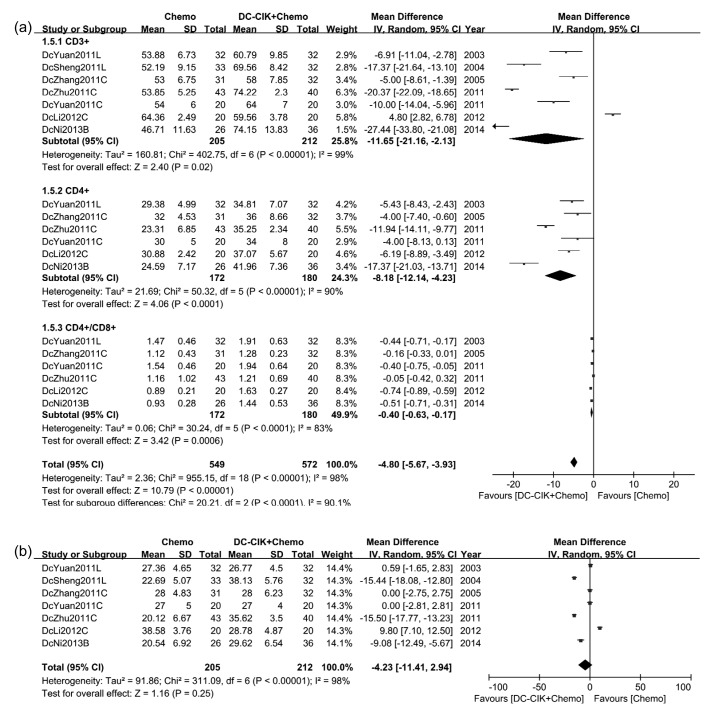

3.5.4. T-lymphocyte subtypes in peripheral blood

Seven studies (417 patients in total) tested the level of CD3+ T-lymphocytes after treatment, among which six concluded that the level of CD3+ T-lymphocytes in the combination group was higher. The other study (Li et al., 2012) reported totally contradicting results. The pooled MD of two groups, which was −11.65 (P=0.02), showed that patients who received DC-CIK and chemotherapy were proven to have a significantly higher level of CD3+ T-lymphocytes. A random-effect analysis model was used (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Levels of T-lymphocyte subtypes of patients in included studies

(a) Comparison of post-treatment T-lymphocytes and ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T-lymphocytes. (b) Comparison of post-treatment CD8+ T-lymphocytes

The level of CD4+ T-lymphocytes and ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T-lymphocytes of patients who received DC-CIK cells treatment were higher. The pooled MD were −8.18 (P<0.0001) and −0.40 (P=0.0006), respectively (Fig. 6a).

CD8+ T-lymphocytes test showed a different result. Three out of seven studies revealed significantly higher level of CD8+ T-lymphocytes in the combination group (Sheng et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2011; Ni et al., 2013); one study reported a contradictory result (Li et al., 2012); and the remaining three did not show any difference between the groups. Pooled MD was −4.23 (P=0.25), suggesting no significant difference in terms of CD8+ T-lymphocytes level between treatment groups (Fig. 6b).

3.6. Comparison of efficacy in different types of cancer

Included were 12 studies focusing on different types of cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast cancer, and gastrointestinal cancer (mainly colorectal cancer). Comparison of OS, clinical response, and T-lymphocytes subtypes in two groups was performed in different types of cancer. Only two of twelve studies focused on breast cancer (Ren et al., 2013; Ni et al., 2013) and most items excepting ORR and DCR were available only in one study (Ni et al., 2013). CD4+, CD4+/CD8+, and DCR of NSCLC and 3-year OS of gastrointestinal cancer were also extracted from one study (Gao et al., 2014). Other comparisons were performed in at least two RCTs.

ORs of 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS between groups in gastrointestinal cancer were all lower than those in NSCLC. ORs of ORR and DCR were similar, but only comparison of breast cancer exhibited statistical significance, which indicated that the combination group showed a better clinical response than the chemo group (Table 3). The combination group showed significantly higher levels of CD3+, CD4+ T-lymphocytes, and CD4+/CD8+ ratio of NSCLC and breast cancer patients. Comparison of CD3+ T-lymphocytes and CD4+/CD8+ ratio of gastrointestinal cancer patients showed no statistical significance. Difference of CD8+ T-lymphocytes between treatment groups in breast cancer showed statistical significance (Table 4).

Table 3.

OR of OS and clinical response between the chemo group and combination group

| Cancer type | 1-year OS | 2-year OS | 3-year OS | ORR | DCR |

| NSCLC | 0.48 (P=0.24) | 0.29 (P=0.04)* | 0.35 (P=0.02)* | 0.67 (P=0.32) | 0.44 (P=0.38) |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 0.16 (P<0.0001)* | 0.27 (P=0.0009)* | 0.14 (P=0.002)* | 0.47 (P=0.06) | 0.52 (P=0.20) |

| Breast cancer | 0.76 (P=0.49) | 0.51 (P=0.04)* | 0.44 (P=0.005)* |

P-value was for overall effect.

P<0.05, difference was considered to be statistically significant

Table 4.

MD of T-lymphocyte subtypes between the chemo group and combination group

| Cancer type | CD3+ | CD4+ | CD4+/CD8+ | CD8+ |

| NSCLC | −12.13 (P=0.02)* | −5.43 (P=0.0004)* | −0.44 (P=0.001)* | −7.41 (P=0.36) |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | −7.64 (P=0.28) | −6.71 (P=0.002)* | −0.35 (P=0.06) | −1.44 (P=0.80) |

| Breast cancer | −27.44 (P<0.00001)* | −17.37 (P<0.00001)* | −0.51 (P<0.00001)* | −9.08 (P<0.00001)* |

P-value was for overall effect.

P<0.05, difference was considered to be statistically significant

3.7. Adverse effects

Fever was the most common adverse effect in the combination group. Transfusion of DC-CIK cells to patients was assumed to induce its occurrence. Most patients experienced fever of 37.2–39.5 °C, and most of them recovered spontaneously without any treatment except some who received antipyretic treatment. Other adverse effects including headache, fatigue, constipation, anemia, vomiting, diarrhea, and skin lesions (rash, acne, pruritus, or petechiae) were non-specific and occurred in a few patients. One case each of Grade III neuritis and shock was reported and relieved after treatment (Table 5).

Table 5.

Adverse effects in included studies

| Study ID | Adverse effects of (number of cases) |

|

| Chemo group | Combination group | |

| DcLi2009L (Li et al., 2009) | None | Fever, headache |

| DcZhong2011L (Zhong et al., 2011) | Anemia (6), leucopenia (13), nausea (13), fever (3), rash, acne, pruritus (1), fatigue (8), febrile neutropenia (1) | Anemia (4), leucopenia (10), nausea (9), fever (10), rash, acne, pruritus (9), fatigue (1), febrile neutropenia (0) |

| DcYuan2011L (Yuan et al., 2011a) | Fever (2), chill (2) | Fever (11), chill (8), shock (1) |

| DcSheng2011L (Sheng et al., 2011) | Arrest of bone-marrow, gastrointestinal reactions | Fever (1), arrest of bone-marrow, gastrointestinal reactions |

| DcZhang2011C (Zhang et al., 2011) | ||

| DcYuan2011C (Yuan et al., 2011b) | None | Fever (2) |

| DcZhu2011C (Zhu et al., 2011) | None | Fever (2) |

| DcLi2012C (Li et al., 2012) | Arrest of bone-marrow, gastrointestinal reactions, peripheral neurotoxicity | Fever (1), arrest of bone-marrow, gastrointestinal reactions, peripheral neurotoxicity |

| DcRen2013B (Ren et al., 2013) | Vomiting (1), diarrhea (1), hepatic complications (2) | Neuritis (1), vomiting (9), diarrhea (12), hepatic complications (4) |

| DcYuan2013L (Yuan et al., 2013) | Anemia, skin petechiae, fatigue, oral pain, constipation, peripheral neuropathy | Fever, anemia, skin petechiae, fatigue, oral pain, constipation, peripheral neuropathy |

| DcNi2013B (Ni et al., 2013) | None | Fever (3) |

| DcGao2014G (Gao et al., 2014) | None | Fever (9) |

None: no adverse effects

4. Discussion

During the early stage of cancer, the immune system is capable of perceiving and eliminating cancer cells, but the efficacy is attenuated with the emergence of the rising number of strange antigens and immunosuppressed status because of the genetic abnormality in the development of cancer. The theory of immunosurveillance and immunoediting insists that cancer cells could escape from a balanced status controlled by the immune system and initiate growth (Dunn et al., 2004). Existence of cancer could mislead myeloid cell differentiation towards immune-suppressor cells and suppress anti-tumor response (Gabrilovich et al., 2012). As the lack of immune regulation has been accepted as one of hallmarks of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011), therapies that enhance anti-tumor immune response are valuable in cancer management.

DCs were indispensable in presenting antigens, secreting cytokines, and inducing anti-tumor immune response in cancers. Anguille et al. (2014) reviewed 38 clinical studies of DC-based immunotherapy in diverse cancers, and they showed that this immunotherapy had a survival benefit and the ability of eliciting an immune response even in advanced-stage patients. In vivo, CIK cells have shown an anti-tumor effect against several kinds of solid tumors in mice with SCID (Jiang et al., 2013). A clinical trial of CIK therapy emerged in 1999, and the number has increased rapidly in the last fifteen years. A systematic review, which included eight trials comparing clinical outcome of CIK and non-CIK therapy, indicated a prolonged OS and DFS in patients with solid cancer (Ma et al., 2012). Liu et al. (2013) studied retinoblastoma cell lines cultured in vitro with tandem carboplatin-DC-CIK, which was preparatively pulsed with tumor antigens, providing evidence that carboplatin combined with DC-CIK cells therapy is superior to carboplatin alone in killing cancer cells. Treatment of carboplatin-DC-CIK was also found to increase cytotoxicity of DC-CIK treatment and sensitize cancer cells to DC-CIK cytotoxic response. Apoptosis was confirmed as a major mechanism underlying CIK cytotoxicity for the first time. According to a meta-analysis of 27 clinical studies on breast cancer, DC-CIK therapy prolonged 1-year survival, improved the quality-of-life, increased immunity function, and decreased cancer antigen (Wang et al., 2014b).

Most of current clinical studies focused on CIK or DC-CIK therapy were performed in China, of which phase I studies and retrospective studies were a major part. Singaporean researchers performed clinical trials on CIK cells, and reported a modest efficacy in hematological malignancy, which may be restricted by imperfect treatment protocol (Linn et al., 2012a; 2012b). Introna et al. (2007; 2010) from Italy conducted two phase I trials showing that the clinical use of CIK cells on leukemic patients after stem cell or cord blood cell transplantation is feasible and well-tolerated. Italian researchers Olioso et al. (2009) tested the CIK therapy in six advanced lymphomas, five metastatic kidney carcinomas, and one hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The results showed that CIK cells could be easily applied clinically, representing a safe and efficient therapy to enhance immune function. The international registry on CIK cells (IRCC, http://www.cik-info.org), established in 2010, is a global platform collecting and evaluating clinical trials about CIK cells, and helping researchers to build up a standard in CIK cell therapy. IRCC provides us with recommended analysis parameters and reporting standards, which will benefit patients on condition that there is more registration (Schmeel et al., 2014).

Meta-analysis is an optimal choice to analyze dozens of clinical studies. The main defects in existing meta-analysis about DC-CIK are that often non-RCTs are included and there is a non-unified regimen of groups. Our meta-analysis brings some new approaches to data reduction. (1) We analyzed current RCTs on DC-CIK therapy and provided an essential reference for evidence-based medicine. (2) Generally, our included studies displayed similar trends in some parameters, but our analysis quantified these trends to make it easier to draw definitive conclusions. (3) The analysis of different types of cancer makes it possible to determine which kind of patient should receive this therapy.

In our study, DC-CIK therapy significantly prolonged OS (OR=0.31, P<0.00001), 1-year DFS (OR=0.16, P=0.01), and 3-year DFS (OR=0.32, P=0.003), but the analysis of the 2-year DFS showed no difference (OR=0.49, P=0.06), probably due to the lack of studies reporting DFS and the following reasons. Transfused CIK cells died out after the termination of treatment, and therefore it may barely prolong short-term survival. Wang et al. (2014b) reported that DC-CIK therapy only prolongs 1-year OS. However, we found the influence of DC-CIK not only on short-term survival but also on long-term survival.

The patients receiving DC-CIK therapy had significantly higher ORR (OR=0.54, P=0.004) and DCR (OR=0.46, P=0.001) than the patients who received chemotherapy only. Another meta-analysis of colon cancer showed significantly higher ORR but not DCR of DC-CIK chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy (Wang et al., 2014c). Our analysis, covering relatively more studies and patients, may be more reliable.

The levels of subtypes of T-lymphocyte in peripheral blood reflect the cellular immunity, which is critical in anti-tumor activity. Patients of various kinds of advanced cancer express less CD3+ and CD4+ T-lymphocytes and more CD8+ T-lymphocytes in peripheral blood than early stage patients or healthy people (Yu et al., 2014). CD4+ T-lymphocytes are considered as helper T-lymphocytes in immune activity, while CD8+ T-lymphocytes induce immune suppression in cancers (McGray et al., 2014). In our study, DC-CIK therapy up-regulated levels of CD3+ T-lymphocytes (OR=−11.65, P=0.02), CD4+ T-lymphocytes (OR=−8.18, P<0.0001), and ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T-lymphocytes (OR=−0.40, P=0.0006), indicating that DC-CIK cells enhance the immune activity.

Efficacy assessments discussed above were performed among NSCLC, gastrointestinal cancer, and breast cancer. According to immunosurveillance theory, cancer originates from the inefficiency of the immune system or the impaired expression of tumor-associated antigens. It is common in different cancer types that cancer cells evade the recognition and elimination of the immune system (Schreiber et al., 2011). Though strengthening the immune response, immunotherapy may exhibit different outcomes in different solid cancers due to their distinct characteristics (Conniot et al., 2014). In our meta-analysis, the combination of chemotherapy and DC-CIK could significantly prolong 2-year OS and 3-year OS, as well as enhance immune activity in NSCLC patients and gastrointestinal cancer patients. For breast cancer, combination therapy showed better ORR and DCR, but the data of T-lymphocyte subtypes and OS were unreliable due to the limited studies (only one study). Relatively, combination therapy represented better applicability in gastrointestinal cancer (gastric cancer and colorectal cancer) than in NSCLC in terms of OS, but the improvements of cellular immunity in NSCLC were more evident than those in gastrointestinal cancer. Owing to the lack of RCTs and incomplete data of included studies, it was hard to draw a convincing conclusion when comparing efficacy between different types of cancer. Discrepancy of outcomes in different cancers may result from the tumor location, blood supply, or unexplained molecular mechanisms. Clinical researches combined with molecular biology studies would help us improve the design of immunotherapy and discover mechanisms underlying sensitivities to immunotherapy. At present, our meta-analysis indicated that immunotherapy significantly improve the OS and immune activity of NSCLC patients, OS of gastrointestinal cancer patients, and clinical response of breast cancer patients. The decision depends on the demand. Our results provide a reference for decision making in cancer treatment.

Our study has several limitations. Included studies were all from China, leading to a regional limitation. Risk of reporting bias may imply insufficient reporting of primary outcome. Moreover, we mainly analyzed treatment efficacy in solid cancer, and more analysis is needed on different types of cancer. To define the appropriate application of combination therapy, standardized research protocols and exhaustive information of both hospitalization and follow-up are required.

In conclusion, immunotherapy of DC-CIK cells improves chemotherapy on clinical response rates, survival of patients, and immune activity of patients with solid cancer, and induces no specific side effects, indicating that DC-CIK is a promising efficient therapeutic option against cancers. Further strict RCTs with no publishing bias should be designed to confirm the immunotherapeutic effects of DC-CIK cells.

Footnotes

Project supported by the Medical and Health Technology Development Project of Shandong Province, China (No. 2014WS0351)

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Xiao-peng LAN, You-gen CHEN, Zheng WANG, Chuan-wei YUAN, Gang-gang WANG, Guo-liang LU, Shao-wei MAO, Xun-bo JIN, and Qing-hua XIA declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Anguille S, Smits EL, Lion E, et al. Clinical use of dendritic cells for cancer therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):e257–e267. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baek S, Lee SJ, Kim MJ, et al. Dendritic cell (DC) vaccine in mouse lung cancer minimal residual model; comparison of monocyte-derived DC vs. hematopoietic stem cell derived-DC. Immune Netw. 2012;12(6):269–276. doi: 10.4110/in.2012.12.6.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conniot J, Silva JM, Fernandes JG, et al. Cancer immunotherapy: nanodelivery approaches for immune cell targeting and tracking. Front Chem. 2014;2:105. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21(2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(4):253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao D, Li C, Xie X, et al. Autologous tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cell immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells improves survival in gastric and colorectal cancer patients. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e93886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hao MZ, Lin HL, Chen Q, et al. Efficacy of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization combined with cytokine-induced killer cell therapy on hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparative study. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29(2):172–177. doi: 10.5732/cjc.009.10410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Introna M, Borleri G, Conti E, et al. Repeated infusions of donor-derived cytokine-induced killer cells in patients relapsing after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a phase I study. Haematologica. 2007;92(7):952–959. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Introna M, Pievani A, Borleri G, et al. Feasibility and safety of adoptive immunotherapy with CIK cells after cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(11):1603–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang J, Wu C, Lu B. Cytokine-induced killer cells promote antitumor immunity. J Transl Med. 2013;11(1):83. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Wang C, Yu J, et al. Dendritic cell-activated cytokine-induced killer cells enhance the anti-tumor effect of chemotherapy on non-small cell lung cancer in patients after surgery. Cytotherapy. 2009;11(8):1076–1083. doi: 10.3109/14653240903121252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S, Li Y, Liang J, et al. The study of clinical application of DC-CIK combined with chemotherapy on colon cancer. Chin J Immunol. 2012;9:835–839. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linn YC, Lau LC, Hui KM. Generation of cytokine-induced killer cells from leukaemic samples with in vitro cytotoxicity against autologous and allogeneic leukaemic blasts. Br J Haematol. 2002;116(1):78–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linn YC, Niam M, Chu S, et al. The anti-tumour activity of allogeneic cytokine-induced killer cells in patients who relapse after allogeneic transplant for haematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(7):957–966. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linn YC, Yong HX, Niam M, et al. A phase I/II clinical trial of autologous cytokine-induced killer cells as adjuvant immunotherapy for acute and chronic myeloid leukemia in clinical remission. Cytotherapy. 2012;14(7):851–859. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.694419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Zhang W, Qi X, et al. Randomized study of autologous cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in metastatic renal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(6):1751–1759. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu P, Chen L, Huang X. The antitumor effects of CIK cells combined with docetaxel against drug-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cell line SPC-A1/DTX in vitro and in vivo . Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009;24(1):91–98. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2008.0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q, Wang Y, Wang H, et al. Tandem therapy for retinoblastoma: immunotherapy and chemotherapy enhance cytotoxicity on retinoblastoma by increasing apoptosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139(8):1357–1372. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1448-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Y, Zhang Z, Tang L, et al. Cytokine-induced killer cells in the treatment of patients with solid carcinomas: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Cytotherapy. 2012;14(4):483–493. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.649185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGray AJ, Hallett R, Bernard D, et al. Immunotherapy-induced CD8+ T cells instigate immune suppression in the tumor. Mol Ther. 2014;22(1):206–218. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ni Z, Fang Q, Liu D, et al. Effect of DC-CIK combined with chemotherapy on immune function, progression-free survival and quality of life of patients with breast cancer. Matern Child Health Care China. 2013;28(31):5134–5137. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niu Q, Wang W, Li Y, et al. Cord blood-derived cytokine-induced killer cells biotherapy combined with second-line chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced solid malignancies. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(4):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olioso P, Giancola R, di Riti M, et al. Immunotherapy with cytokine induced killer cells in solid and hematopoietic tumours: a pilot clinical trial. Hematol Oncol. 2009;27(3):130–139. doi: 10.1002/hon.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palucka K, Banchereau J, Mellman I. Designing vaccines based on biology of human dendritic cell subsets. Immunity. 2010;33(4):464–478. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan CC, Huang ZL, Li W, et al. Serum alpha-fetoprotein measurement in predicting clinical outcome related to autologous cytokine-induced killer cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergone minimally invasive therapy. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29(6):596–602. doi: 10.5732/cjc.009.10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren J, Di L, Song G, et al. Selections of appropriate regimen of high-dose chemotherapy combined with adoptive cellular therapy with dendritic and cytokine-induced killer cells improved progression-free and overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: reargument of such contentious therapeutic preferences. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15(10):780–788. doi: 10.1007/s12094-013-1001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmeel LC, Schmeel FC, Coch C, et al. Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells in cancer immunotherapy: report of the international registry on CIK cells (IRCC) J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;141(5):839–849. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1864-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt-Wolf IG, Negrin RS, Kiem HP, et al. Use of a SCID mouse/human lymphoma model to evaluate cytokine-induced killer cells with potent antitumor cell activity. J Exp Med. 1991;174(1):139–149. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331(6024):1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheng C, Bao F, Xu S, et al. Clinical research on chemotherapy combined with dendritic cell-cytokine induced killer cells for non-small cell lung cancer. J Pract Oncol. 2011;26(5):503–506. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi L, Zhou Q, Wu J, et al. Efficacy of adjuvant immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol Immun. 2012;61(12):2251–2259. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1289-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thanendrarajan S, Nowak M, Abken H, et al. Combining cytokine-induced killer cells with vaccination in cancer immunotherapy: more than one plus one? Leuk Res. 2011;35(9):1136–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D, Zhang B, Gao H, et al. Clinical research of genetically modified dendritic cells in combination with cytokine-induced killer cell treatment in advanced renal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):251. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang ZX, Cao JX, Wang M, et al. Adoptive cellular immunotherapy for the treatment of patients with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Cytotherapy. 2014;16(7):934–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang ZX, Cao JX, Liu ZP, et al. Combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy for colon cancer in china: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(4):1095–1106. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i4.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu D, Han Y, Zhao Q, et al. CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ lymphocyte subgroups and their surface receptors NKG2D and NKG2A in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(6):2685–2688. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.6.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan J, Peng D, Li J. Clinical effects of administering dendritic cells and cytokine induced killer cell combined with chemo therapy in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Orthop. 2011;16(12):1910–1911. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan J, Peng D, Li J, et al. Clinical research of dendritic cells combined with cytokine induced killer cells therapy for advanced colorectal cancer. Chin Gen Pract. 2011;12:4139–4141. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan Y, Niu L, Mu F, et al. Therapeutic outcomes of combining cryotherapy, chemotherapy and DC-CIK immunotherapy in the treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Cryobiology. 2013;67(2):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Geng J, Han Z, et al. Clinical effects of treatment of dendritic cells combined with cytokine induced killer cells therapy in patients with advanced colon carcinoma. Acta Acad Med Xuzhou. 2011;31(7):457–459. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong R, Teng J, Han B, et al. Dendritic cells combining with cytokine-induced killer cells synergize chemotherapy in patients with late-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immun. 2011;60(10):1497–1502. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1060-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhong R, Han B, Zhong H. A prospective study of the efficacy of a combination of autologous dendritic cells, cytokine-induced killer cells, and chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(2):987–994. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu Y, Liu J, Zhang N, et al. Clinical effects of treatment with comprehensive multiple autologous immune cells in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Acta Acad Med Xuzhou. 2011;9:631–636. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]