Abstract

Cyclophosphamide (CP) is a widely used anti-cancer agent; however, it can also induce serious male infertility. There are currently no effective drugs to alleviate this side-effect. L-Carnitine has been used to treat male infertility, but whether it can be used to protect against CP-induced male infertility is still unclear. This study aims to explore the effect and mechanism of L-carnitine in male infertility induced by CP. CP was used to establish an animal model. After three weeks of treatment, rats were sacrificed and testis and serum were harvested for further evaluation. Testosterone and estrogen levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Testicular injury was examined by hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining, and germ-cell apoptosis was evaluated by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL). The expression of LC3 and Beclin-1 was examined by immunohistochemistry, Western blot, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), respectively. Compared with the CP group, L-carnitine significantly increases sperm motility, viability, and testosterone level (P<0.05). Western blot and real-time PCR results showed that L-carnitine treatment can significantly up-regulate the LC3-II and Beclin-1 expression in the CP+L-carnitine group when compared with the control group (P<0.05). In addition, TUNEL-positive cells were also more numerous in the CP group; however, L-carnitine can effectively retard cell apoptosis in the CP+L-carnitine group. In conclusion, L-carnitine contributes to the inhibition of cell apoptosis and the modulation of autophagy in protecting CP-induced testicular injury. These results suggest the applicability of L-carnitine in the treatment of male infertility.

Keywords: L-Carnitine, Infertility, Cyclophosphamide, LC3, Beclin-1

1. Introduction

A decline in fertility due to radioactive environmental exposure or toxic anti-cancer drugs has received attention recently. Approximately 10% of couples worldwide are affected by reduced fertility (Tasi et al., 2013). Cyclophosphamide (CP) is a drug which is widely used for treating cancer; however, it can cause serious side-effects, such as male infertility. The causative mechanisms of male infertility are still poorly understood and there is still a lack of efficient drugs for this condition.

L-Carnitine has been used to treat male infertility in recent years (Kanter et al., 2010). As a small water-soluble molecule, L-carnitine plays an important role in sperm metabolism, leading to sperm maturation, motility, and the spermatogenic process (Topcu-Tarladacalisir et al., 2009). Matalliotakis et al. (2000) have reported that the initiation of sperm motility is closely related to an increase of L-carnitine in the epididymal lumen and L-acetyl-carnitine in sperm cells. Therefore, in the present study, we wanted to test whether L-carnitine could also play a role in treating anti-cancer-drug-induced infertility and investigate its possible mechanism. CP-induced infertile male rats were used in the study, and the protective role of L-carnitine on the spermatogenic process and its effect in autophagy in the testis were examined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal model

Male Wistar rats, six weeks old and weighing 180–200 g, were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), and housed in rooms at (24±1) °C, (50±10)% humidity, and with a 12-h light/dark cycle. All procedures followed the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine and performed in accordance with guiding principles for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Rats were randomly assigned to a control group (n=8), CP group (n=8), and CP+L-carnitine group (n=8). The CP group and CP+L-carnitine group received an intraperitoneal injection of CP (35 mg/kg) for a period of 5 d. The control group received a saline solution. The CP+L-carnitine group was orally given L-carnitine at a dose of 2.1 ml/(kg∙d), and other groups were given distilled water every day. Fifty days later, all animals were sacrificed and the testes and epididymis were removed for further examination. The serum was stored at −80 °C until use.

2.2. Preparation of sperm suspension

The caudal epididymis was dissected and placed in modified Hank’s balanced salt solution (M-HBSS) for 10 min at 37 °C. The solution was then gently filtered through nylon gauze and centrifuged for 5 min at 800 r/min. The cells were re-suspended in 1 ml fresh M199 medium (Sigma Chemical, USA), from which 10 ml of the sperm suspension was used for further assessment.

2.3. Assessment of spermatozoon motility and viability

To determine the number of viable spermatozoa, a drop of spermatozoon suspension was uniformly smeared on to a clean glass hemocytometer, and the mean number of viable spermatozoa in at least four of the corner larger squares (1 mm2) was counted. Those cells at the upper and right boundaries were ignored, and the overlapping cells were counted as one spermatozoon. The computer-assisted spermatozoon assay (CASA) with a spermatozoon motility analyzer (Weili Medical Treatment, China) was used to assess spermatozoon motility. Those with fast progressive motility were labeled as Level A, and those with modest motility were marked as Level B. Those without motility were dead sperm and were labeled as Level C.

Spermatozoon viability was visualized by eosin and nigrosin staining. Briefly, the spermatozoon suspension was mixed with 1% eosin (0.01 g/ml) and 10% nigrosin (0.1 g/ml), and a smear of the mixture placed on a clean glass slide, which was allowed to air-dry. The slide was then observed by light microscopy. Those stained pink were interpreted as dead spermatozoa and those unstained live spermatozoa. The viability of spermatozoa was expressed as a percentage.

2.4. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Plasma testosterone levels were measured by enzyme immunoassay (Cayman Chemical Co., Michigan, USA).

2.5. RNA extraction and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent and the first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). The relative messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of LC3-II and Beclin-1 were measured by real-time PCR (ABI 7500). Amplification was performed as follows: denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min following by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at temperatures listed in Table 1 for 30 s, and elongation for 2 min at 72 °C. The nucleotide sequences of the primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers

| Name | Sequence (5′→3′) | Product size (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Cycle number |

| LC3-II | Forward: CATGGGCACAGATGAAGACAC Reverse: GCCAGATGTTCATCCACTTTC | 210 | 60 | 40 |

| Beclin-1 | Forward: ACCAGGAGGAAGCTCAGTACC Reverse: CAGGCAGCATTGATTTCATTC | 253 | 60 | 40 |

| β-Actin | Forward: ATCGTGCGTGACATTAAGGAGAAG Reverse: AGGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAGTG | 239 | 60 | 40 |

2.6. Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from the pancreas and INS-1 cells with RIPA lysis buffer (Applygen, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After centrifugation of homogenate, supernatant was used for determination of protein concentration by the Bradford protein assay. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked for 2 h with 5% (0.05 g/ml) skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies of LC3 (1:1000 (v/v); Cell Signal, USA), Beclin-1 (1:1000 (v/v); MBL, Japan), and β-actin (1:5000 (v/v); Sungene Biotech, Tianjin, China) overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were then incubated with secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:5000 (v/v; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The protein bands were visualized with chemiluminescence reagent (ECL, Engreen Biosystem, Beijing, China).

2.7. Immunohistochemistry for LC3 and Beclin-1

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded sections. Briefly, testis was cut into 4-μm sections and mounted on polylysine-coated slides. The sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in xylene and graded ethanol. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min to reduce nonspecific binding and then incubated with primary antibody against LC3 (Cell Signal, USA) and Beclin-1 (MBL, Japan). The slides were then incubated with anti-mouse/rabbit polymerized horseradish peroxidase (poly HRP) and positive stains were detected with GTVision™ III Detection System (Mo & Rb, Gene Tech, Shanghai, China) and diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen buffer. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Cowin Biotech, Beijing, China). Digital morphometric analyses were performed using a Leica optical microscope with the Leica Qwin Plus analysis software DM5000 (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

2.8. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)

The numbers of apoptotic cells in testes were detected by TUNEL, using an in situ detection kit (Roche, Indianapolis, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were rehydrated and incubated in proteinase K solution (20 g/ml) for 5 min and rinsed in PBS. Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by 3% hydrogen peroxide. The specimens were incubated with equilibration buffer for 5 min and exposed to TUNEL reaction buffer (TdT enzyme and reaction buffer) in a dark humidified chamber for 1 h at 37 °C. Samples were then incubated with a stop/wash buffer for 5 min, then with anti-digoxigenin-peroxidase conjugate at room temperature. Sections were then treated with DAB (ZSGB-Bio, China) for 1 min. Cells, which were stained brown, were considered as positive. At least 50 round-shaped seminiferous tubule cross-sections from testicular sections of each rat (n=4) were observed.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments. SPSS 18.0 was used for statistical analysis. Comparisons between the two groups were analyzed by Student’s t test. Comparisons of three groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Scheffe’s test. P<0.05 was considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of L-carnitine on spermatozoon quality

Compared with the control group, CP can significantly decrease the Level A and Level B sperm (P<0.05) in the CP group. However, L-carnitine can efficiently protect sperm degradation (P<0.05) when compared with the CP group. However, there was no significant difference in spermatozoon density between the CP and CP+L-carnitine groups (P>0.05) (Table 2). In addition, we observed that L-carnitine can significantly increase the spermatozoon activity rate and motility rate when compared with the CP group (P<0.05; Table 3).

Table 2.

Effect of L-carnitine on spermatozoon quality

| Group | Spermatozoon of Level A (%) | Spermatozoon of Level B (%) | Spermatozoon density (×106 ml−1) |

| Control | 3.373±0.879 | 11.002±3.702 | 74.162±27.496 |

| CP | 1.182±0.952* | 3.697±1.240* | 41.340±15.010* |

| CP+L-carnitine | 2.557±0.975# | 8.280±5.630# | 38.473±13.049* |

Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=6).

P<0.05, compared with the control group

P<0.05, compared with the CP group

Table 3.

Effect of L-carnitine on spermatozoon activity

| Group | Spermatozoon activity rate (%) | Spermatozoon motility rate (%) |

| Control | 14.375±3.559 | 42.603±6.059 |

| CP | 5.878±3.420* | 27.920±5.773* |

| CP+L-carnitine | 10.837±4.742# | 35.593±10.644# |

Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=6).

P<0.05, compared with the control group

P<0.05, compared with the CP group

3.2. Testosterone and estradiol

Compared with the control group, CP injection could dramatically decrease the serum testosterone level and increase the level of estradiol (P<0.05). However, L-carnitine can effectively retard the decrease of testosterone (P<0.05). The estradiol level in the CP+L-carnitine group was also significantly lower than that in the CP group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of L-carnitine on serum hormone

| Group | Testosterone (nmol/L) | Estradiol (pg/ml) |

| Control | 1.43±0.57 | 1.79±0.05 |

| CP | 0.74±0.22* | 1.89±0.03* |

| CP+L-carnitine | 0.99±0.14# | 1.78±0.05# |

Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=6).

P<0.05, compared with the control group

P<0.05, compared with the CP group

3.3. Histology and immunohistochemistry

There were no obviously pathological changes in morphology of seminiferous tubules in the control groups. However, in the CP group, we found that the testes showed moderate degeneration of spermatogenic cells, diffuse edema of interstitial cells, and significantly fewer spermatozoa in tubules. In the CP+L-carnitine group, the testes showed nearly normal seminiferous tubules with the quantity of spermatogenic cells increased; the disturbance of spermatogenic cell arrangement was much slighter when compared with the CP group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Testicular sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) from Bouin’s-fixed paraffin-embedded testes

(a) Testis from the control group revealed normal testicular morphology for seminiferous tubule architecture and interstitial regions. (b) Testis from the CP group revealed degeneration in the seminiferous tubule epithelium and loss of germinal cells. (c) Testis from the CP+L-carnitine group revealed tubular architecture containing regular seminiferous tubular epithelium in places and spermatozoa in the lumen

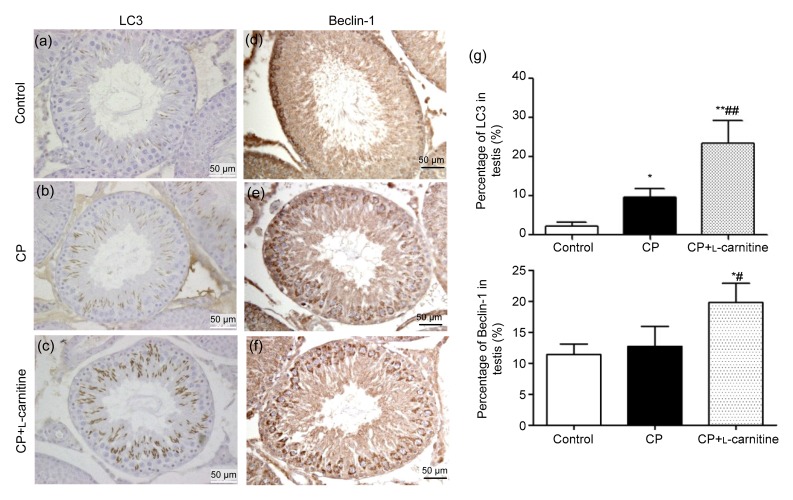

The immunohistochemistry results showed that CP can induce LC3 and Beclin-1 expression either in the CP or CP+L-carnitine group. Nevertheless, when compared with the CP group, L-carnitine treatment can significantly increase the expression of LC3 (P<0.01) and Beclin-1 (P<0.05) in the CP+L-carnitine group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemistry of LC3 and Beclin-1 in testis

Staining of LC3 (a, b, c) and Beclin-1 (d, e, f) in the control, CP, and CP+L-carnitine groups, respectively, and their quantitative values of staining (g). Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=6). * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, compared with the control group; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01, compared with the CP group

3.4. Apoptosis of testes

The number of apoptotic cells in the control group was negligible. However, rats injected with CP showed a noticeable increase of apoptotic cells. Nevertheless, treatment with L-carnitine can significantly retard germ cell apoptosis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

TUNEL staining of testes

(a) Testis from the control group. Few TUNEL-positive germ cells are observed in the seminiferous epithelium. (b) Testis from the CP group. Apoptotic cells are frequently found in the seminiferous epithelium. (c) Testis from the CP+L-carnitine group. Apoptotic cells are significantly decreased. The positive cells were stained with brown color (Note: for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article)

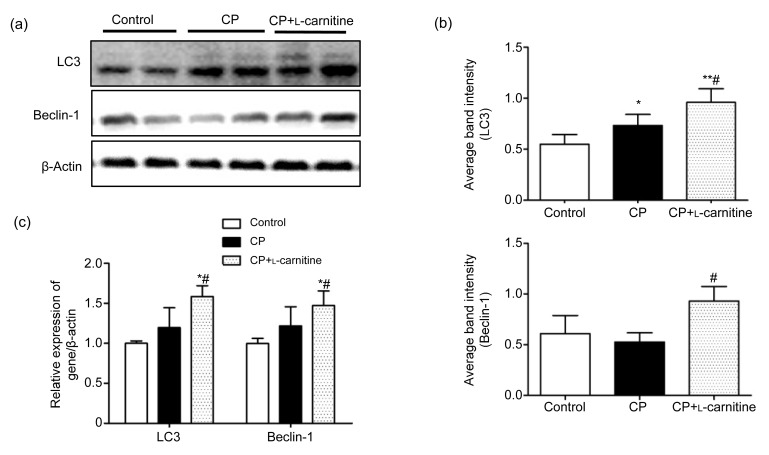

3.5. Western blot and mRNA expression

The expression of LC3 and Beclin-1 in testes was examined by Western blot and real-time PCR. It was observed that L-carnitine can significantly increase the LC3 and Beclin-1 expression both in terms of protein and RNA when compared with the CP group (P<0.05; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Abundances of LC3 and Beclin-1 mRNA and proteins

(a) The typical picture of Western blot analyses of LC3 and Beclin-1 expression in testicular tissue. (b) Quantitative values of Western blot. (c) Relative LC3 and Beclin-1 mRNA levels compared with β-actin. Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=6). * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, compared with the control group; # P<0.05, compared with the CP group

4. Discussion

Spermatogenesis is a highly complex and precise process, which is dependent on well-balanced germ cell proliferation, differentiation, and death in the testis (Malaguarnera et al., 2007). However, this process can be disturbed by CP, which is commonly used in acute regimens for the treatment of various neoplastic diseases and in chronic regimens for the treatment of autoimmune disorders. CP is widely used as an anti-cancer agent, which, however, can cause several adverse effects including reproductive toxicity, since it can inhibit proliferation of cells on account of its DNA-damaging effect (Tripathi and Jena, 2008). Although reports on CP-induced reproductive toxicity are available, little is known about the mechanisms (Kim et al., 2012; Aghaei et al., 2014; Comish et al., 2014). In our study, we have discovered that CP can cause a noticeable decrease in serum testosterone level and increase the apoptotic rate in the testis, thus giving rise to a decline in spermatozoon motility and viability and leading to infertility. Currently, there are no effective methods to avoid these side effects.

L-Carnitine has been studied for over a century (Koeth et al., 2013). As an endogenous substrate, it is widely distributed among tissues including the male reproductive organs (Hinton et al., 1979). The high concentration of L-carnitine in testicular tissues leads to an increase in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, which is used to produce energy for spermatozoon respiration and motility. Previous research has suggested that lowering of L-carnitine in testis and epididymis was attributable to the adverse effect on epididymal function to transport and/or concentrate L-carnitine (Kanter et al., 2010). Demirdag et al. (2004) and Aliabadi et al. (2013) have shown that it can protect the liver from injury by carbon tetrachloride and decreased lipid peroxidation. In this study, we have discovered that L-carnitine could improve the germ cell motility and quality with the total number of Level A and Level B spermatozoa being dramatically increased. Serum hormone levels such as those of testosterone were also increased. The improvement of these indices was better explaining the curative efficacy of L-carnitine in male reproductive system.

Autophagy is a conserved catabolic process, which can regulate the degradation of a cell’s own components such as chromosomes through the lysosomal system (Kroemer and Levine, 2008). It is the most common event in every cell type to preserve the balance between the synthesis and degradation (Ohsumi, 2001). During the autophagy process, LC3 can be promoted to convert from LC3-I to LC3-II and translocated on to isolated membranes and autophagosomes (Tanida et al., 2008). Thus, the amount of LC3-II level correlates closely with the number of autophagosomes (Jiang and Mizushima, 2014). It has been showed that the accumulation of autophagosomes is a crucial process for the regulation of cell death (Choi et al., 2013). Xie et al. (2008) had reported that LC3 can efficiently protect Mc3T3 cells from apoptosis. Ye et al. (2014) reported that Beclin-1 knockdown can exacerbate neointimal formation after rat carotid injury. In our experiments, we have observed that L-carnitine can increase LC3-II and Beclin-1 levels after CP injection and decrease germ cell apoptosis. This may partly explain why L-carnitine protects germ cells from apoptosis.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, although many studies have shown the effect of L-carnitine in common infertility (Trasler and Robaire, 1988; Moradi et al., 2010; Banihani et al., 2014), there are no studies of L-carnitine in relation to CP-induced infertility. Our results, for the first time, have shown a promising effect and one of its possible mechanisms. Nevertheless, we believe that autophagy may not be the ultimate way, through which L-carnitine can influence male infertility. Based on our results, further human and animal studies are needed to give clearer evidence of L-carnitine in relation to male infertility.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Natural Sciene Foundation of China (No. 81402814)

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Bin ZHU, Yan-fei ZHENG, Yue-ying ZHANG, Yun-song CAO, Lei ZHANG, Xin-gang LI, Teng LIU, Zhao-zhu JIAO, Qi WANG, and Zhi-gang ZHAO declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

References

- 1.Aghaei S, Nikzad H, Taghizadeh M, et al. Protective effect of pumpkin seed extract on sperm characteristics, biochemical parameters and epididymal histology in adult male rats treated with cyclophosphamide. Andrologia. 2014;46(8):927–935. doi: 10.1111/and.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aliabadi E, Karimi F, Rasti M, et al. Effects of L-carnitine and pentoxifylline on the activity of lactate dehydrogenase C4 isozyme and motility of testicular spermatozoa in mice. J Reprod Infertil. 2013;14(2):56–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banihani S, Agarwal A, Sharma R, et al. Cryoprotective effect of L-carnitine on motility, vitality and DNA oxidation of human spermatozoa. Andrologia. 2014;46(6):637–641. doi: 10.1111/and.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B. Autophagy in human health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(7):651–662. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1205406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comish PB, Drumond AL, Kinnell HL, et al. Fetal cyclophosphamide exposure induces testicular cancer and reduced spermatogenesis and ovarian follicle numbers in mice. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e93311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demirdag K, Bahcecioglu IH, Ozercan IH, et al. Role of L-carnitine in the prevention of acute liver damage induced by carbon tetrachloride in rats. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(3):333–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinton BT, Snoswell AM, Setchell BP. The concentration of carnitine in the luminal fluid of the testis and epididymis of the rat and some other mammals. J Reprod Fertil. 1979;56(1):105–111. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0560105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang P, Mizushima N. Autophagy and human diseases. Cell Res. 2014;24(1):69–79. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanter M, Topcu-Tarladacalisir Y, Parlar S. Antiapoptotic effect of L-carnitine on testicular irradiation in rats. J Mol Histol. 2010;41(2-3):121–128. doi: 10.1007/s10735-010-9267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim W, Kim SH, Park SK, et al. Astragalus membranaceus ameliorates reproductive toxicity induced by cyclophosphamide in male mice. Phytother Res. 2012;26(9):1418–1421. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):576–585. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroemer G, Levine B. Autophagic cell death: the story of a misnomer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(12):1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/nrm2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malaguarnera M, Cammalleri L, Gargante MP, et al. L-Carnitine treatment reduces severity of physical and mental fatigue and increases cognitive functions in centenarians: a randomized and controlled clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(6):1738–1744. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matalliotakis I, Koumantaki Y, Evageliou A, et al. L-Carnitine levels in the seminal plasma of fertile and infertile men: correlation with sperm quality. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2000;45(3):236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moradi M, Moradi A, Alemi M, et al. Safety and efficacy of clomiphene citrate and L-carnitine in idiopathic male infertility: a comparative study. Urol J. 2010;7(3):188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohsumi Y. Molecular dissection of autophagy: two ubiquitin-like systems. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(3):211–216. doi: 10.1038/35056522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and autophagy. In: Deretic C, editor. Autophagosome and Phagosome. Methods in Molecular Biology™. Vol. 445. Humana Press; 2008. pp. 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tasi YC, Chao HC, Chung CL, et al. Characterization of 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase, HIBADH, as a sperm-motility marker. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(4):505–512. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-9954-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topcu-Tarladacalisir Y, Kanter M, Uzal MC. Role of L-carnitine in the prevention of seminiferous tubules damage induced by gamma radiation: a light and electron microscopic study. Arch Toxicol. 2009;83(8):735–746. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0382-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trasler JM, Robaire B. Effects of cyclophosphamide on selected cytosolic and mitochondrial enzymes in the epididymis of the rat. J Androl. 1988;9(2):142–152. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.1988.tb01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tripathi DN, Jena GB. Astaxanthin inhibits cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of cyclophosphamide in mice germ cells. Toxicology. 2008;248(2-3):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie H, Tang SY, Li H, et al. L-Carnitine protects against apoptosis of murine MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells. Amino Acids. 2008;35(2):419–423. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0598-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye LX, Yu J, Liang YX, et al. Beclin 1 knockdown retards re-endothelialization and exacerbates neointimal formation via a crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237(1):146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]