Abstract

Abrogation of errant signaling along the MAPK pathway through the inhibition of B-RAF kinase is a validated approach for the treatment of pathway-dependent cancers. We report the development of imidazo-benzimidazoles as potent B-RAF inhibitors. Robust in vivo efficacy coupled with correlating pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PKPD) and PD-efficacy relationships led to the identification of RAF265, 1, which has advanced into clinical trials.

Keywords: B-RAF, MAP, VEGF, serine/threonine kinases, tyrosine kinases

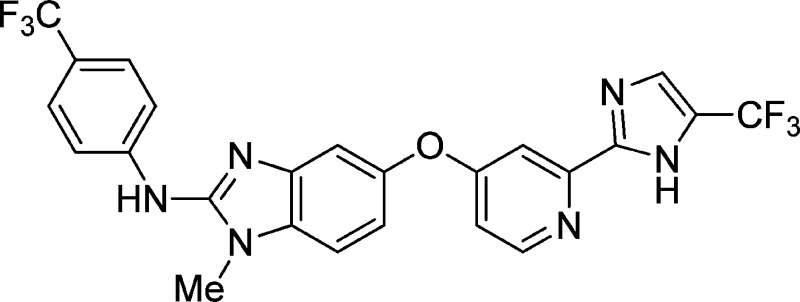

The MAPK signaling pathway, consisting of RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK, transduces input from cell surface receptors to nuclear transcription factors thereby regulating cellular proliferation, differentiation, and survival.1 Dysregulation of this pathway through an activating mutation in B-RAF (V600E) occurs in ∼50% of melanomas and has made RAF the subject of many drug discovery efforts.2 Validation for targeting B-RAFV600E as an effective chemotherapeutic approach has been provided by the recent approval of vemurafenib (Roche) and dabrafenib (GSK) by the FDA for the treatment of metastatic melanoma (Figure 1).3−5

Figure 1.

Structures of vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and sorafenib.

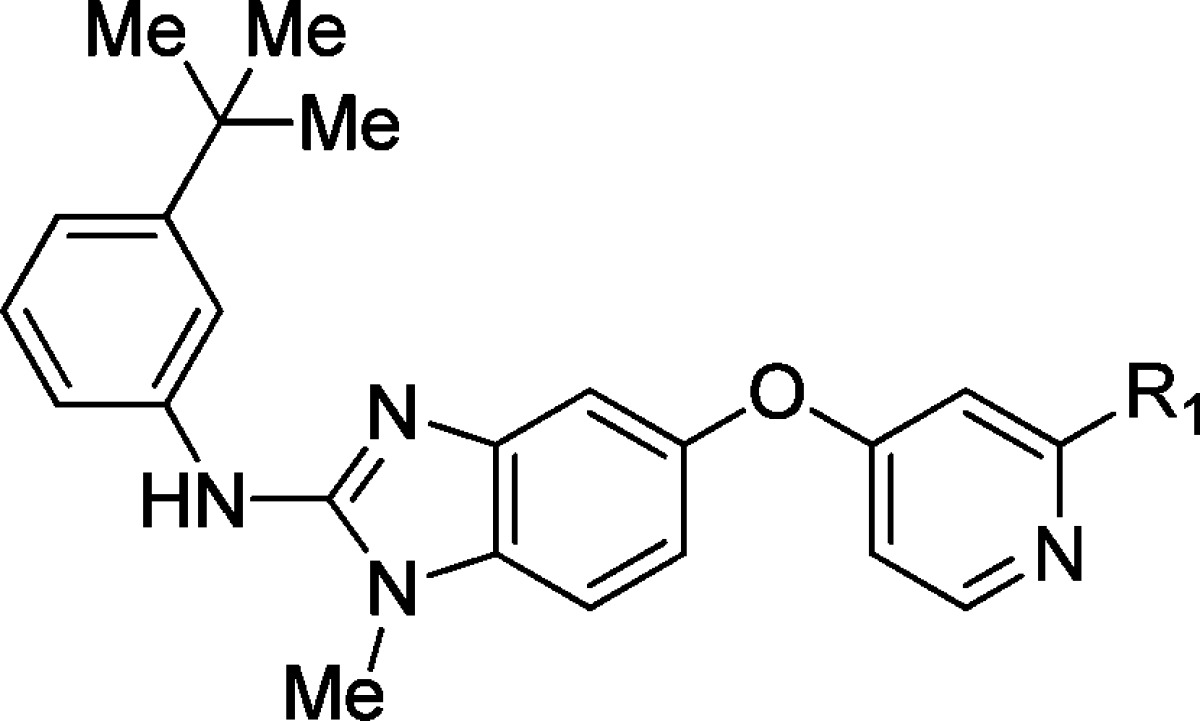

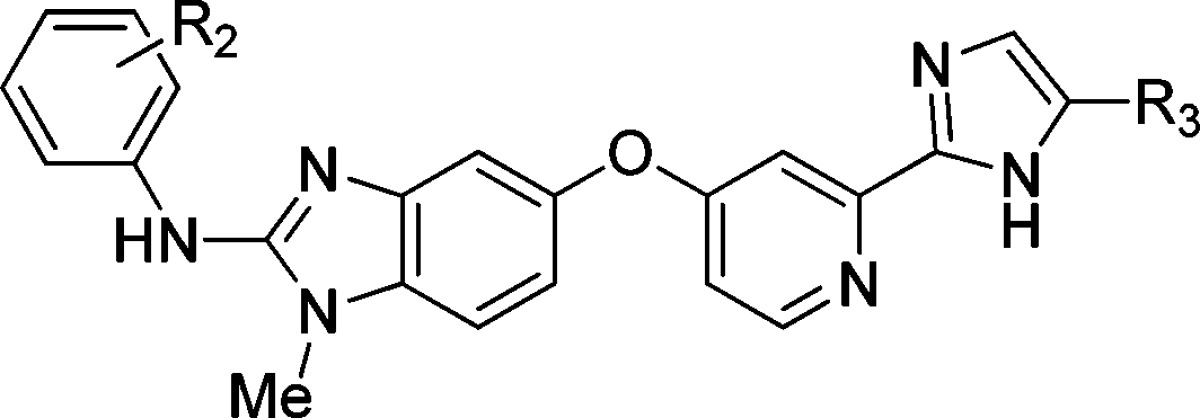

Previous publications from our laboratories have described the development of the 2-arylaminobenzimidazole scaffold as a platform for improved mut-RAF potency and pharmacokinetics over sorafenib (Bayer, Figure 1), an earlier receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of renal cell and hepatocellular carcinoma.6−8 In this report, we describe our continued efforts in this area, which resulted in the discovery of RAF265 (1), a potent inhibitor of B-RAFV600E with complementary VEGFR and PDGFR activity.

As reported previously, amido-2-arylaminobenzimidazoles, such as 2 (Table 1), have demonstrated potent biochemical inhibition as well as cellular activity in target modulation and proliferation assays against SKMEL-28, a B-RAFV600E harboring melanoma cell line.5−7,9

Table 1. Key Amide Transformationsa.

| Cpd | R1 | B-RAFV600Eb | pERK SKMEL-28c | SKMEL-28d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | –CONHMe | 0.045 (1) | 0.28 (3) | 0.90 (3) |

| 3 | –NHCOMe | 0.003 (1) | 0.044 (7) | 0.18 (8) |

| 4 | 2-imidazolyl | 0.090 (1) | 0.39 (1) |

Further development of the series did not result in further improvement in cellular potency; however, a simple and effective inversion of the amide connectivity as embodied in 3 realized a marked increase in cellular potency.7 Unfortunately, some substituted reverse amide analogues suffered from plasma instability, and an alternative moiety was sought. Utilizing an isostere replacement approach, cyclization of the forward amide of 2 led to the simple imidazole analogue 4, which demonstrated a similar in vitro potency profile and provided a suitable starting point for further investigation.

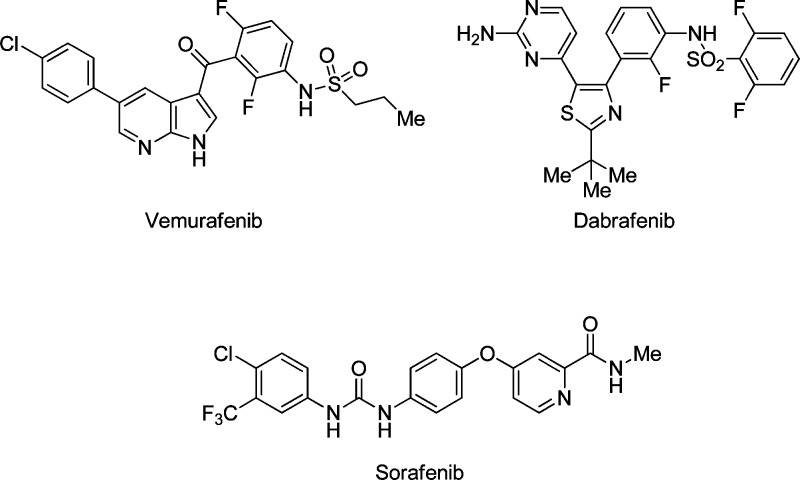

The general synthetic route for the imidazole series is represented by the synthesis of 1 as depicted in Scheme 1. The central phenyl-pyridyl ether 6 was assembled from the SNAr reaction of chloropyridine 5 with 3-nitro-4-aminophenol. Methylation of the anilino nitrogen was accomplished using phase transfer catalysis to give 7.10,11 Reduction of the t-butyl ester using LAH under strict temperature control, followed by NaBH4 and MnO2 oxidation furnished aldehyde 8. Debus–Radziszewski cyclization with an in situ generated glyoxal derived from 1,1-dibromo-3,3,3-trifluoroacetone furnished the corresponding imidazole 9.12 Reduction of the nitroarene followed by addition of 4-trifluoromethylphenyl thioisocyanate and FeCl3-promoted ring cyclization provided 1.13 All compounds where biological data is presented have >95% purity as determined by HPLC.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 3-nitro-4-aminophenol, K2CO3, DMSO, 100 °C, 74%; (b) TFAA, DCM, 0 °C; Me2SO4, TBACl, 10% NaOH, 76%; (c) LAH, THF 0 °C; NaBH4, 46%; (d) MnO2, DCM, 58%; (e) 1,1-dibromo-3,3,3-trifluoroacetone, NaOAc, water, 100 °C; NH4OH, MeOH rt, 91%; (f) 10% Pd/C, H2, MeOH/EtOAc, 96%; (g) 4-trifluoromethylphenyl thioisocyanate, FeCl3, 40–60%.

The simple, unadorned imidazole 4, while providing a useful benchmark against the previous series, did not offer the cellular potency desired and resulted in a significant CYP liability (CYP3A4 IC50 = 1.8 μM). An SAR campaign probing the anilide and imidazole substitution patterns was undertaken to address cellular potency and CYP3A4 inhibition of this series (Table 2).

Table 2. Selected Data from Anilide and Imidazole SAR Surveya.

| Cpd | R2 | R3 | pERK SKMEL-28b | SKMEL-28c | CYP3A4d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 3-tBu | H | 0.39 (1) | 1.8 (2) | |

| 10 | 3-tBu | Ph | 0.48 (2) | 1.1 (1) | 7.1 (1) |

| 11 | 3-tBu | CF3 | 0.12 (2) | 0.12 (2) | 10 (3) |

| 12 | 4-tBu | CF3 | 0.13 (1) | 0.23 (1) | 34 (1) |

| 13 | 2-F, 5-tBu | CF3 | 0.042 (1) | 0.050 (1) | 3.3 (1) |

| 14 | 3-CF3 | CF3 | 0.78 (1) | 1.62 (1) | >40 (1) |

| 15 | 2-F, 5-CF3 | CF3 | 0.21 (4) | 0.6 (4) | 26 (2) |

| 16 | 2-F, 5-CF3 | Me | 0.62 (1) | 0.74 (1) | 3.4 (1) |

| 1 | 4-CF3 | CF3 | 0.14 (18) | 0.16 (12) | >40 (3) |

IC50 in μM. Numbers in parentheses represent number of determinations.

CYP3A4 inhbition assay using midazolam as subtrate. Assay variability within 2-fold of mean value for applicable entries. See Supporting Information for CYP3A4 assay conditions and isoform inhibition of 1.

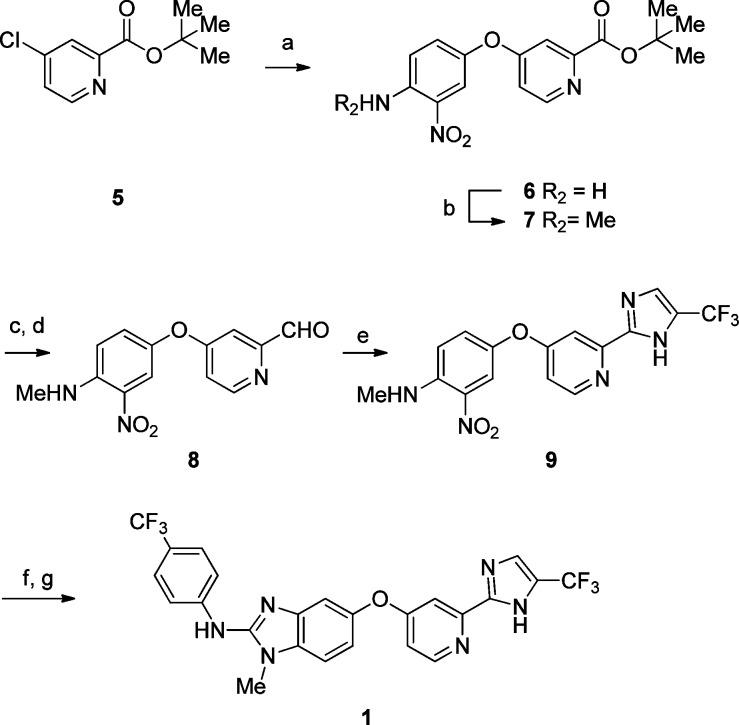

Holding with previously reported SAR trends, 3- and 4-position branched alkyl substituents of the anilide ring conferred potency (4, 10–12).4,5 For meta-substituted analogues, introduction of a fluorine at the 2-position gave a further boost in cellular potency (13, 15). Unfortunately, all 3- and 5-alkyl substituted analogues suffered from poor exposure in pharmacokinetic (PK) studies. A solution was found in the para- and meta-CF3 analogues (1, 14), which provided a similar level of potency as with the alkyl analogues along with greater metabolic stability. In examining the imidazole substitution pattern, it was observed that electron withdrawing groups improved cellular potency as illustrated in the matched pair analyses of 4, 11 and 15, 16. Gratifyingly, imidazole substitution also provided incremental reduction in CYP3A4 inhibition14 (4, 10, 11); however, the CYP3A4 profile could be further modulated by the anilide substitution pattern. Moving the tBu group from the 3-position to the 4-position (12) resulted in an improvement in CYP3A4 selectivity, which also translated into the corresponding CF3 analogue 1. With a favorable balance of cellular potency and CYP3A4 selectivity, 1 was selected for further investigation.

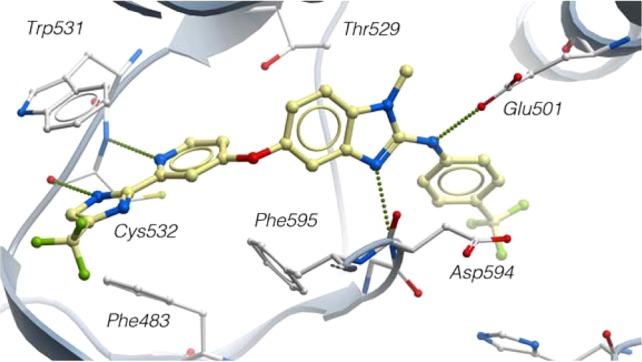

The crystal structure of 1 in truncated wt-B-RAF provided insight as to how the molecule interacts with the target protein (Figure 2).200 Binding occurred through a Type II, inactive-like conformation where the DFG loop has adopted an “out” conformation.15 Of interest is the hinge region where the imidazole is situated between Trp531 and Phe483. The imidazole NH interacts with the carbonyl of Cys532, suggesting that a potential role of the 5-CF3 substituent is to acidify the NH-bond and facilitate a stronger hydrogen bonding interaction. The pyridyl moiety makes a second hydrogen bond to Cys532 that completes an efficient bidentate interaction. The ring benzimidazolo nitrogen and the anilide NH are found to hydrogen bond with the NH backbone of Asp594 of the DFG loop and Glu501 of the αC-helix, respectively.16 The NMe of the benzimidazole fills the selectivity pocket partially defined by the “gatekeeper” residue, Thr529.

Figure 2.

Co-crystal structure of 1 bound to truncated wt-B-RAF at 3.2 Å resolution.

RAF265 (1) was found to be a potent inhibitor of B-RAFV600E, wt-B-RAF, and C-RAF with IC50s of 0.0005, 0.070, and 0.019 μM, respectively. The kinase selectivity profile of 1 bore similarities to inhibitors of other serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases, such as sorafenib.15−18 All specific hydrogen bonds between 1 and wt-B-RAF are with residues that are conserved among the kinases (e.g Glu501 and Asp594). Within the chemical series, consistent off targets included VEGFR, PDGFβ, and c-Kit, all of which share a threonine or a similarly sized valine residue at the gatekeeper position in the “back” or “selectivity” pocket (Table 3).

Table 3. Biochemical Activities Against Select Tyrosine Kinasesa.

| Cpd | B-RAFV600E | VEGFR | c-KIT | PDGFRβ | LCK | FYN | SRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.045 | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.065 | 0.005 | |

| 3 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| 4 | 0.090 | 0.030 | 0.020 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.040 | |

| 11 | 0.055 | 0.070 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 2.0 | 0.22 | >6.0 |

| 1 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.006 | >6.0 | >10 | >10 |

IC50 in μM. All entries are single determinations. See ref (18) for a broader kinase survey of 1.

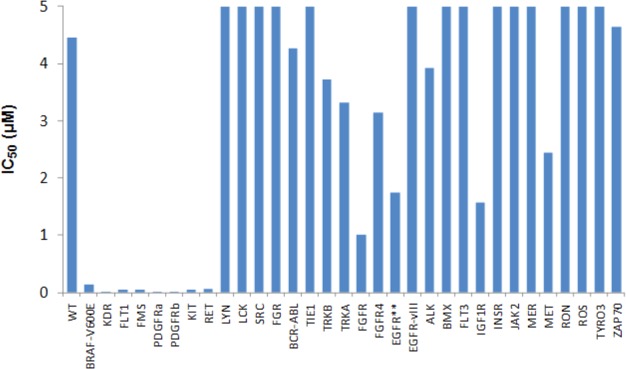

Kinase profiling of each of the benzimidazolo archetypes (2, 3, 4) indicated little or no discrimination against a significant segment of tyrosine kinases. However, within the imidazole series, substitution at imidazole in the hinge region provided a handle to address selectivity against the SRC family of kinases (11, 1). To understand the selectivity profile in a cellular setting, 1 was evaluated in a panel of Ba/F3 cells whose profileration was dependent on a range of protein kinases (Figure 3).19

Figure 3.

Inhibitory activity of 1 against kinase dependent Ba/F3 cell lines. IC50 in μM. All entries are single determinations.

The activity against these kinase-dependent cell lines (KDR, KIT, PDGFRb) recapitulated the biochemical findings and were corroborated by a cell based receptor phosphorylation assay (VEGFR IC50 = 0.19 μM). This level of activity was similar to that observed against Ba/F3-B-RAFV600E (IC50 = 0.14 μM) and in the SKMEL-28 proliferation assay. Conversely, the Ba/F3 cells expressing LCK, FYN, and SRC were not inhibited reflecting success in achieving selectivity against these kinases. Together, these data indicated that along with potent inhibition of B-RAFV600E, 1 also inhibited the VEGFR and PDGFR family of kinases, which play critical roles in tumor angiogenesis.

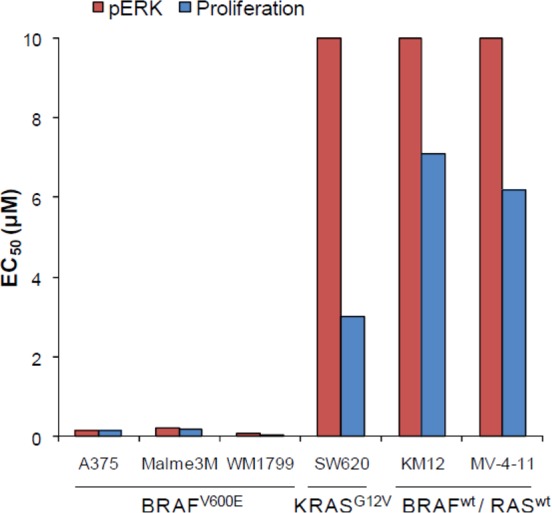

Pathway inhibition and antiproliferative effects were evaluated in a small panel of tumor cell lines (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

In vitro target modulation and antiproliferation of RAF265 on MAPK-dependent tumor cell lines. IC50 in μM. All entries are single determinations. See Supporting Information for assay details.

In melanoma tumor cell lines expressing B-RAFV600E (A375, Malme-3M, and WM-1799), 1 decreased phospho-ERK and inhibited proliferation with IC50 ranging from 0.04 to 0.2 μM. In contrast, cell lines that expressed wt-B-RAF, 1, failed to suppress phospho-ERK levels and had weak antiproliferative activity.

Owing to the size and lipophilic nature of the molecule (MW = 518, cLog P > 5), it was unsurprising that 1 exhibited poor kinetic aqueous solubility (∼1 μM) and high plasma protein binding (>99% PPB in mouse, rat, dog, and human).20 Despite these drawbacks, 1 exhibited good to moderate oral bioavailability across species, with dog being the lowest, when dosed in single dose PK studies (Table 4). Total plasma clearance is very low relative to hepatic blood flow, and the plasma half-life across species is greater than 24 h, indicating the possibility of accumulation in multidose settings.

Table 4. In Vivo Pharmacokinetics of 1 Across Speciesa.

| parameters | mouse | rat | dog | monkey |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dose (mpk, iv/po) | 5, 30 | 5, 20 | 1.25, 5 | 1, 5 |

| %F | 51 | >95 | 35 | 48 |

| AUC∞, po (μM·h) | 4300 | 450 | 35 | 48 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.5 |

| Vss (L/kg) | 0.5 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 2.9 |

| t1/2 (h) | 41 | 46 | 27 | 28 |

Administered as a solution in 60%PEG400/40% PG.

In mouse PK studies, the high plasma protein binding and a low volume of distribution of 1 would suggest sequestration within the plasma compartment. In separate efficacy studies in A375M xenograft models, 1 was able to distribute to the target and exert a pronounced pharmacological effect (Figures 5 and 6).

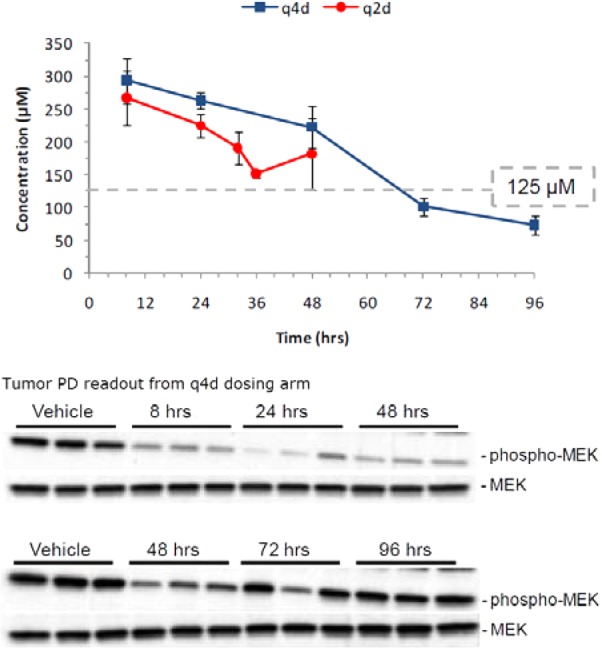

Figure 5.

PKPD snapshot from A375M model xenograft model. PD sampling taken at noted time points post-third dose of the q4d arm. The PD readouts of the 48 h time point are two separate blots of the same tumor lysate sample. See Supporting Information for efficacy data and experimental details.

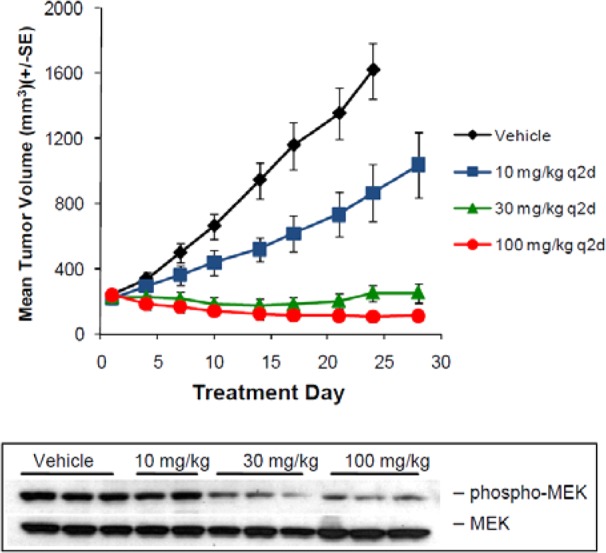

Figure 6.

Efficacy of 1 in A375M mouse xenograft. PD sampling taken 4 h post-third dose. Less than 15% body weight loss was observed in the 100 mg/kg q2d dosing arm. See Supporting Information for more details.

Seeking to take advantage of the long PK half-life, a 32 day multidose efficacy study examining the effect of intermittent dosing regimens on target coverage was undertaken. Tumors from a subset of mice from each study arm were harvested at intervals post-third dose, and the corresponding lysates were assayed for phospho-MEK levels by Western blot analysis (Figure 5). Dosing q2d maintained a Cmin trough level of ∼125 μM, which corrected for mouse plasma protein (99.6%) yielding an effective free Cmin of ∼0.5 μM (A375M IC50 = 0.16 μM). The pharmacodynamic (PD) readout from the q4d arm indicated significant target suppression out to 48 h followed by complete signal recovery at 96 h, indicating that the q2d dosing regimen would be optimal for target coverage.

To characterize the dose–response relationship, 1 was dosed orally q2d at 10, 30, and 100 mg/kg in a 28 day mouse efficacy study (Figure 6). Consistent with the results of the previous study in Figure 5, 1 induced tumor regressions at the 100 mg/kg, while at 30 mg/kg resulted in robust stasis or tumor growth inhibition, and the 10 mg/kg dose demonstrated modest inhibition of tumor growth relative to vehicle treated animals. The PD results corroborated the earlier PKPD findings with the 30 and 100 mg/kg dose, which resulted in significant reductions in phospho-MEK levels compared to tumors from the vehicle group, while the 10 mg/kg dose did not appreciably alter phospho-MEK levels.

To conclude, we have developed a novel chemical series derived from 2-arylaminobenzimidazoles, which were optimized for cellular potency while balancing kinase selectivity and ADME properties. These efforts resulted in the identification of 1 as a potent inhibitor of B-RAFV600E with complementary VEGFR and PDGFR activity that demonstrated potent in vivo target modulation and efficacy. Further development of this molecule resulted in the advancement into clinical trials for the treatment of metastatic melanoma.21

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Mina Aikawa and Susan Fong for their support on cellular and biochemical assays, Ahmad Hashash on formulations, Jeremy Murray on preliminary structural work, and Oncotest GmBH (Breisgrau, Germany) for providing support on xenograft PKPD models.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental details for the synthesis and characterization of select compounds, procedures for the biochemical and cellular assays, in vivo analyses, and crystallographic conditions. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/ml500526p.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Santarpia L.; Lippman S. M.; El- Naggar A. K. Targeting the MAPK-RAS-RAF signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2012, 16, 103–119. 10.1517/14728222.2011.645805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H.; Bignell G. R.; Cox C.; Stephens P.; Edkins S.; Clegg S.; Teague J.; Woffendin H.; Garnett M. J.; Bottomley W.; Davis N.; Dicks E.; Ewing R.; Floyd Y.; Gray K.; Shall S.; Hawes R.; Hughes J.; Kosmidou V.; Menzies A.; Mould C.; Parker A.; Stevens C.; Watt S.; Hooper S.; Wilson R.; Jayatilake H.; Gusterson B. A.; Cooper C.; Shipley J.; Hargrave D.; Pritchard-Jones K.; Maitland N.; Chenevix-Trench G.; Riggins G. J.; Bigner D. D.; Palmieri G.; Cossu A.; Flanagan A.; Nicholson A.; Ho J. W. C.; Leueng S. Y.; Yuen S. T.; Weber B. L.; Seigler H. F.; Darrow T. L.; Paterson H.; Marais R.; Marshall C. J.; Wooster R.; Stratton M. R.; Futreal P. A. Mutations of the B-RAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954. 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Liberal J.; Larkin J. New RAF kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2014, 15, 1235–1245. 10.1517/14656566.2014.911286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G.; Tsai J.; Zhang J.; Zhang C.; Ibrahim P.; Nolop K.; Hirth P. Vemurafenib: the first drug approved for BRAF-mutant cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 873–886. 10.1038/nrd3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheault T. R.; Stellwagen J. C.; Adjabeng G. M.; Hornberger K. R.; Petrov K. G.; Waterson A. G.; Dickerson S. H.; Mook R. A.; Laquerre S. G.; King A. J.; Rossanese O. W.; Arnone M. R.; Smitheman K. N.; Kane-Carson L. S.; Han C.; Moorthy G. S.; Moss K. G.; Uehling D. E. Discovery of Dabrafenib: A selective inhibitor of Raf kinases with antitumor activity against B-Raf driven tumors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 358–362. 10.1021/ml4000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramurthy S.; Subramanian S.; Aikawa M.; Amiri P.; Costales A.; Dove J.; Fong S.; Jansen J. M.; Levine B.; Ma S.; McBride C. M.; Michaelian J.; Pick T.; Poon D. J.; Girish S.; Shafer C. M.; Stuart D.; Sung L.; Renhowe P. A. Design and Synthesis of Orally Bioavailable Benzimidazoles as RAF kinasse inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7049–7052. 10.1021/jm801050k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S.; Costales A.; Williams T.; Levine B.; McBride C.; Poon D.; Amiri P.; Renhowe P.; Shafer C.; Stuart D.; Verhagen J.; Ramurthy S. Design and synthesis of orally bioavailable benzimidazole reverse amides as pan-RAF kinase inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 989–992. 10.1021/ml5002272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S.; Carter C.; Lynch M.; Lowinger T.; Dumas J.; Smith R. A.; Schwartz B.; Simantov R.; Kelley S. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5, 835–844. 10.1038/nrd2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J.; Lee J. T.; Wang W.; Zhang J.; Cho H.; Mamo S.; Bremer R.; Gillette S.; Kong J.; Haass N. K.; Sproesser K.; Li L.; Smalley K. S. M.; Fong D.; Zhu Y. L.; Marimuthu A.; Nguyen H.; Lam B.; Liu J.; Cheung I.; Rice J.; Suzuki Y.; Luu C.; Settachatgul C.; Shellooe R.; Cantwell J.; Kim S. H.; Schlessinger J.; Zhange K. Y. J.; West B. L.; Powell B.; Habets G.; Zhang C.; Ibrahim P. N.; Hirth P.; Artis D. R.; Herlyn M.; Bollag G. Discovery of a selective inhibitor or oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 3041–3046. 10.1073/pnas.0711741105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. A.; Rizzo C. J. A “one-pot” phase transfer alkylation/hydrolysis of o-nitrotrifluoroacetanilides. A convenient route to N-alkyl 0-phenylenediamines. Synth. Commun. 1996, 26, 4065–4080. 10.1080/00397919608003827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKillop A.; Fiaud J. C.; Hug R. P. The use of phase- transfer catalysis for the synthesis of phenol ethers. Tetrahedron 1974, 30, 1379–1382. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)97250-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J. J.; Kasinger P. A.; Novello F. C.; Sprague J. M. 4-Trifluoromethylimidazoles and 5-(4-pyridyl)-1,2,4-triazoles, new classes of xanthine oxidase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 1975, 18, 895–900. 10.1021/jm00243a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An alternative process procedure has been described:Artman G.; Solovay C. F.; Adams C. M.; Diaz B.; Dimitroff M.; Ehara T.; Gu D.; Ma F.; Liu D.; Miller B. R.; Pick T. E.; Poon D. J.; Ryckman D.; Siesel D. A.; Stillwell B. S.; Swiftney T.; van Dyck J. P.; Zhang C.; Ji N. One pot synthesis of aminobenzimidazoles using 2-chloro-1,2-dimethylimidazolium chloride (DMC). Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 5319–5321. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.07.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagarajan S.; Chakravarty P. K.; Zhou B.; Fisher M. H.; Wyvratt M. J.; Lyons K.; Klatt T.; Li X.; Kumar S.; Williams B.; Felix J.; Priest B. T.; Brochu R. M.; Warren V.; Smith M.; Garcia M.; Kaczorowski G. J.; Martin W. J.; Abbadie C.; McGowan E.; Jochnowitz N.; Parsons W. H. Substitutied biaryl oxazoles, imidazoles, and thiazoles as sodium channel blockers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 5536–5540. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) with the accession code 5ct7.

- Zhang J.; Yang P. L.; Gray N. S. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 28–39. 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. L.; DeMorin F. F.; Paras N. A.; Huang Q.; Petkus J. K.; Doherty E. M.; Nixey T.; Kim J. L.; Whittington D. A.; Epstein L. F.; Lee M. R.; Rose M. J.; Babij C.; Fernando M.; Hess K.; Le Q.; Beltran P.; Carnahan J. Selective inhibitors of the mutant-B-RAF Pathway: Discovery of a Potent and Orally Bioavailable Aminoisoquinoline. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6189–6192. 10.1021/jm901081g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R.; Crouthamel M. C.; Rominger D. H.; Gontarek R. R.; Tummino P. J.; Levin R. A.; King A. G. Myelosupression and kinase selectivity of multikinase angiogenesis inhibitors. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 101, 1717–1723. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A broad kinase survey was conducted on RAF265 and other kinase inhibitors:Karaman M. W.; Herrgard S.; Treiber D. K.; Gallant P.; Atteridge C. E.; Campbell B. T.; Chan K. W.; Ciceri P.; Davis M. I.; Edeen P. T.; Faraoni R.; Floyd M.; Hunt J. P.; Lockhart D. J.; Milanov Z. V.; Morrison M. J.; Pallares G.; Patel H. K.; Pritchard S.; Wodicka L. M.; Zarrinkar P. P. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 127–132. 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick J. S.; Janes J.; Kim S.; Chang J. Y.; Sipes D. G.; Gunderson D.; Jarnes L.; Matzen J. T.; Garcia M. E.; Hood T. L.; Beigi R.; Cia G.; Harig R. A.; Asatryan H.; Yan S. F.; Zhou Y.; Gu X. J.; Saadat A.; Zhou V.; King F. J.; Shaw C. M.; Su A. I.; Downs R.; Gray N. S.; Schultz P. G.; Warmuth M.; Caldwell J. S. An efficient rapid system for profiling the cellular activities of molecular libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 3153–3158. 10.1073/pnas.0511292103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnott J. A.; Planey S. L. The influence of lipophilicity in drug discovery and design. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2012, 7, 863–875. 10.1517/17460441.2012.714363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals. A Study to Evaluate RAF265, an Oral Drug Administered to Subjects With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Melanoma. http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00304525 (NLM Identifier: NCT00304525).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.