Abstract

Methods and techniques to measure and image beyond the state-of-the-art have always been influential in propelling basic science and technology. Because current technologies are venturing into nanoscopic and molecular-scale fabrication, atomic-scale measurement techniques are inevitable. One such emerging sensing method uses the spins associated with nitrogen-vacancy (NV) defects in diamond. The uniqueness of this NV sensor is its atomic size and ability to perform precision sensing under ambient conditions conveniently using light and microwaves (MW). These advantages have unique applications in nanoscale sensing and imaging of magnetic fields from nuclear spins in single biomolecules. During the last few years, several encouraging results have emerged towards the realization of an NV spin-based molecular structure microscope. Here, we present a projection-reconstruction method that retrieves the three-dimensional structure of a single molecule from the nuclear spin noise signatures. We validate this method using numerical simulations and reconstruct the structure of a molecular phantom β-cyclodextrin, revealing the characteristic toroidal shape.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a widely applied technique that infers chemical signatures through magnetic dipolar interactions. Magnetic fields arising from nuclear spins are weak, so conventional NMR measurement requires a sizable number of spins, approximately 1015, to achieve reasonable signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)1. This sensitivity limitation permits only ensemble-averaged measurements and forbid any possibilities of studying individual molecules or their interactions. There is a continuous effort to use hybrid detection strategies to improve the sensitivity and, thus, achieve single molecular sensing with spin information. Spin-polarized scanning tunneling microscopy (STM)2 and magnetic resonance force microscopy (MRFM)3 have displayed remarkable abilities in imaging structures with chemical contrast to single electron spins3 and few thousand nuclear spins4. Their extreme sensitivity imposes restrictions on the permissible noise floor, so the microscope is operable under cryogenic conditions.

It was the first room-temperature manipulation of a single spin associated with the nitrogen-vacancy (NV) defects in diamond5 that brought the NV center into quantum limelight. In this seminal paper, Gruber et al. envisaged that material properties can be probed at a local level using optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) of NV spin combined with high magnetic field gradients ensemble averaging5. Later, Chernobrod and Berman proposed scanning-probe schemes to image isolated electron spins based on ODMR of photoluminescent nanoprobes6. Perceiving the uniqueness of single NV spin and combining coherent manipulation schemes7,8, independently proposals9,10 and experimental results11,12 emerged, ascertaining NV spin as an attractive sensor for precision magnetometry in nanoscale13,14,15.

Spin sensor based on NV defects is unique because it is operable under ambient conditions and achieves sufficient sensitivity to detect few nuclear spins16,17,18,19,20. The hydrogen atoms that are substantially present in biomolecules possess nuclear spins. Mapping spin densities with molecular-scale resolution would aid in unraveling the structure of an isolated biomolecule21,22. This application motivates to develop an NV spin-based molecular structure microscope23,24,25,26. The microscope would have immense use in studying structural details of heterogeneous single molecules and complexes when other structural biology tools are prohibitively difficult to use. For example, NV spin-based molecular structure microscope would find profound implications in the structure elucidation of intrinsically disordered structures, such as the prion class of proteins (PrP). This family of proteins is known to play a central role in many neurodegenerative diseases27. Understanding the structure-function relationship of this protein family will be crucial in developing drugs to prevent and cure these maladies.

The NV spin is a high dynamic range precision sensor28,29; its bandwidth is limited only by the coherence time and MW driving-fields30,31. The broadband sensitivity has an additional advantage because multiplexed signals can be sensed32,33,34. Fully exploiting this advantage, we present a projection-reconstruction method pertaining to an NV spin microscope that encodes the spin information of a single molecule and retrieves its three-dimensional structure. We analyze this method using numerical simulations on a phantom molecule β-cyclodextrin. The results show distinct structural features that clearly indicate the applicability of this technique to image isolated biomolecules with chemical specificity. The parameters chosen for the analysis are experimentally viable4,35,36,37, and the method is realizable using state-of-the-art NV sensing systems23,24,35. We also outline some possible improvements in the microscope scheme to make the spin imaging more efficient and versatile.

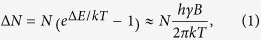

At equilibrium, an ensemble of nuclear spins following the Boltzmann distribution tends to have a tiny fraction of spins down in excess of spins up. The expression for this population difference is given by the Boltzmann equation:

|

where N is the number of spins, ΔE is the energy level difference, k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, h is the Planck constant, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, and B is the magnetic field. For room temperature and low-field conditions (ΔE ≪ k), an approximation is made in equation (1). The spins reorient their states (↑-↓, ↓-↑) with a characteristic time constant while conserving this excess population. The average value of this excess spins remains constant while the root mean square (r.m.s.) value of this fluctuation over any period is given by . This statistical fluctuation in the net magnetization signal arising from uncompensated spins is called spin noise, and it is relevant when dealing with small numbers of spins. Combining spatial encoding using the magnetic field gradients and passively acquiring spin noise signals, Müller and Jerschow demonstrated nuclear specific imaging without using RF radiation38. The spin noise signals become prominent when we consider fewer than 106 spins. Considering solid-state organic samples with spin densities of 5 × 1022 spins/cm3, this quantity of spins creates a nanoscale voxel36. Spin noise signals arising from a few thousand nuclear spins were sensed using MRFM and used to reveal a 3D assembly of a virus4. More recently, using NV defects close to the surface of a diamond, several groups were able to detect the nuclear spin noise from molecules placed on the surface under ambient conditions19,20,25.

. This statistical fluctuation in the net magnetization signal arising from uncompensated spins is called spin noise, and it is relevant when dealing with small numbers of spins. Combining spatial encoding using the magnetic field gradients and passively acquiring spin noise signals, Müller and Jerschow demonstrated nuclear specific imaging without using RF radiation38. The spin noise signals become prominent when we consider fewer than 106 spins. Considering solid-state organic samples with spin densities of 5 × 1022 spins/cm3, this quantity of spins creates a nanoscale voxel36. Spin noise signals arising from a few thousand nuclear spins were sensed using MRFM and used to reveal a 3D assembly of a virus4. More recently, using NV defects close to the surface of a diamond, several groups were able to detect the nuclear spin noise from molecules placed on the surface under ambient conditions19,20,25.

If a magnetic field sensor is ultra-sensitive and especially sample of interest is in nanoscale13, it is convenient to use spin noise based imaging. The advantage being, this sensing method does not require polarization or driving nuclear spins. Dynamic decoupling sequences, such as (XY8)n=16, are used for sensing spin noise using NV. The method uses pulse timings to remove all asynchronous interactions and selectively tune only to the desired nuclear spin Larmor frequency17,19,25. The NV coherence signal is recorded by varying the interpulse timings over a desired range. The acquired signal is deconvoluted with the corresponding filter function of the pulse sequence to retrieve the power spectral density of noise or the spin noise spectrum39. This approach has been proved to be sensitive down to a single nuclear spin in the vicinity20 as well as to a few thousand of nuclear spins at distances exceeding 5 nm19. Correlation spectroscopy approaches are able to achieve sub kHz line widths32 even for shallow NV spins40. The spin sensing results clearly demonstrate the potential of NV spin sensor as a prominent choice for realizing a molecular structure microscope that is operable under ambient conditions.

Spin imaging method

Several different schemes are currently being considered for nanoscale magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using NV-sensors: scanning the probe12,15,41, scanning the sample23,24 and scanning the gradient12,35. The first two rely on varying the relative distance and orientation of the sensor to the sample, thereby sensing/imaging the near-field magnetic interaction between the NV spin and the spins from the sample. This sensing could be performed either by passively monitoring the spin fluctuation19 or by driving sub-selected nuclear spins by RF irradiation18. This approach is particularly suitable when dilute spins need to be imaged in a sample or for samples that are sizable. These methods read spin signal voxel-by-voxel in a raster scanning method, so they are relatively slow but have the advantage of not needing elaborate reconstruction23,24. For the method presented here to image a single molecule, we employ scanning the gradient scheme12,35.

Here, we present a three-dimensional imaging method that is especially suiting for nanoscale-MRI using NV spins. The multiplexed spin-microscopy method uses a projection-reconstruction technique to retrieve the structure of a biomolecule. Figure 1a shows a schematic of the setup that is similar to those utilized in nanoscale magnetometry schemes12,35,42. We place the sample of interest (a biomolecule) on the diamond surface very close to a shallowly created NV defect43. Achieving this could be perceived as a difficult task, but recent advancements in dip pen nanolithography (DPN)44 and micro-contact printing (μCP)45 for biomolecules have been able to deposit molecules with nanometer precision. Another approach is to cover the surface with monolayer of molecules, or to use sub-monolayer concentrations but ensuring that a single biomolecule is able to be located within few nm from the NV sensor.

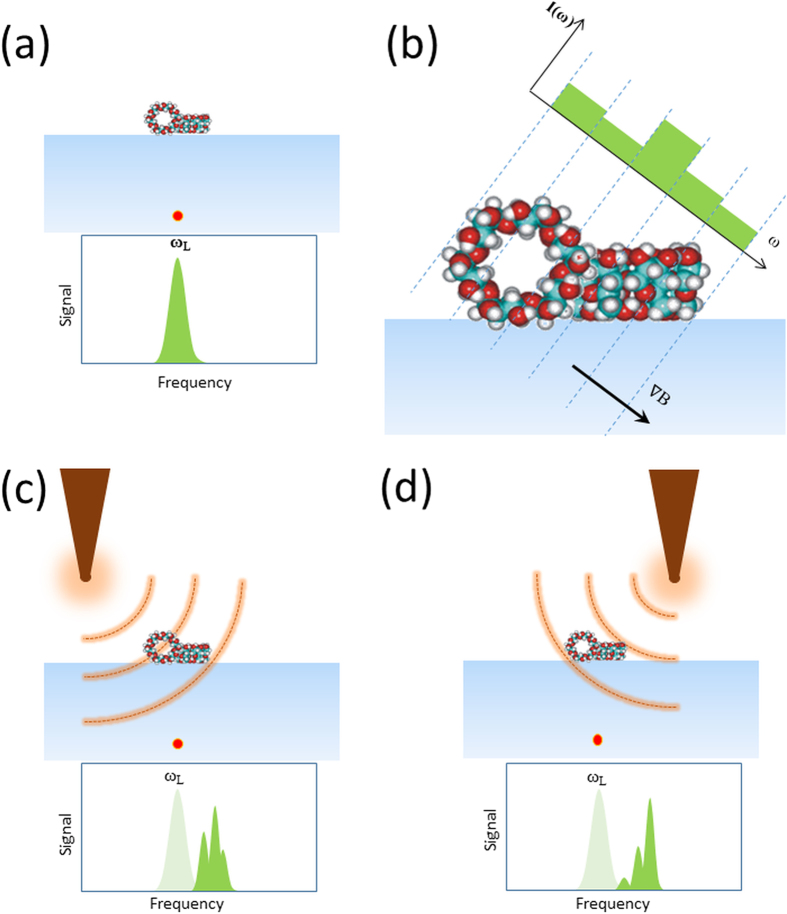

Figure 1. Schematics of the molecular scale spatial encoding using magnetic field gradients.

(a) Schematic representation of a biomolecule in the vicinity of an NV-center; ωL in the inset signifies the Larmor peak position in the spectrum. (b) Gradient encoding of the molecule’s proton density; a spectrum is presented in direction of the gradient vector. (c,d) Schematic representation of different magnetic field gradients induced by an approached magnetic tip; insets: their influence on the spectrum.

The encoding stage proceeds in the following manner: a shaped magnetic tip is positioned such that we subject the sample to a magnetic field gradient on molecular scales (2–5 G/nm)4,35. In this condition, nuclear spins present in the biomolecule precess at their Larmor frequencies depending on their apparent positions along the gradient (Fig. 1b). The spin noise signal of the precessing protons from the sample is recorded using an NV center in close proximity19. Because of the presence of a field gradient on the sample, fine-features appear in the noise spectrum. These unique spectral signatures correspond to nuclear spin signal contributions from various isomagnetic field slices38 (Fig. 1c,d). Directions of field gradient applied to the molecule are changed by moving the magnetic tip to several locations. This gradient gives distinct projection perspectives while the spin noise spectrum contains the corresponding nuclear spin distribution information. These signals are indexed using the coordinates of the magnetic tip with respect to the NV defect as Θ and Φ (measured using high-resolution ODMR) and are stored in a 3D array of S(Θ, Φ, ω) values. We require encoding only in one hemisphere because of the linear dependence (thus redundancy) of the opposite gradient directions. For a simple treatment, we assume the gradients to have small curvatures when the magnetic tip to NV sensor distances are approximately 100 nm (i.e. a far field). This assumption is along the lines of published works and is valid for imaging biomolecules of approximately 5 nm in size at one time4,35. The effects of non-axial field from the gradient source influencing the spin properties of NV could be minimized by applying a static field (B0) of appropriate strength that is well aligned with the NV axis.

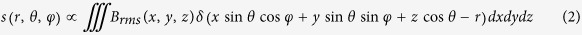

The reconstruction procedure is as follows: by knowing the complete magnetic field distribution from the tip42, we can calculate the gradient orientation (θ, φ) at the sample location for any tip position (Θ, Φ) and rescale the spectral information to spatial information in 1D: ω = γr∇B. In this way, the encoded data set matrix dimensions are transformed into θ, φ and r.

|

Here, Brms(x, y, z) is the magnetic field fluctuation caused by the number of nuclear spins N(x, y, z)contained in the respective isomagnetic field slices. As nuclear spin Larmor frequencies within every slice are identical, they all contribute to same frequency component in noise spectrum38,46.

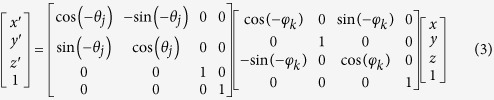

Therefore, the 1D signal we recorded is an integrated effect from the spins in the respective planes (refer to equation (2)). The next procedure follows along the lines of a filtered back-projection principle to remove high-frequency noise and projection artifacts. Here, we should ensure appropriate quadratic filters because the signal is a plane integral but not a line integral as in X-ray computed tomography (CT)46. The rescaled signal s(r, θ, φ) is filtered using a quadratic cutoff in the frequency domain. We perform the reconstruction in the following way; an image array is created with n3 dummy elements in three dimensions I(x, y, z). Any desired index ri, θj, φk from the signal array is chosen, and the corresponding value s(ri, θj, φk) is copied to the image array at location index z = ri. The values are normalized to n and replicated to every cell in the xy-plane at the location z = ri. The elements of the xy-plane are rotated to the values −θj, −φk following the transformation given by affine matrices shown in equation (3).

|

The values are then cumulatively added to the dummy elements and stored in the transformed index. This procedure is repeated for every element in the signal array so that the corresponding transformed array accumulates values from all of the encoded projections. The transformed array with units in nm contains raw projection-reconstructed images. This array is then rescaled to account for the point spread function of NV spin and single proton interaction23. The resulting 3D matrix carries nuclear spin density in every element and contains three-dimensional image of the molecule.

Results

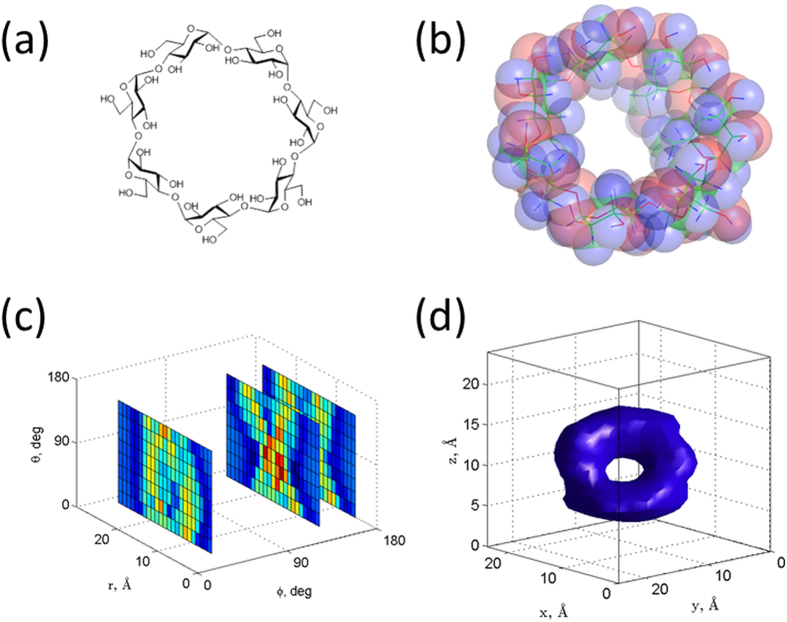

To evaluate this technique, we considered a simple molecule of β-cyclodextrin as a molecular phantom. This molecule has a toroidal structure with an outer diameter of 1.5 nm and an inner void of 0.6 nm (Fig. 2a). We specifically selected this molecule so that we could easily visualize the extent of the structural details that can be revealed by reconstruction. We used the crystallographic data of β-cyclodextrin from the Protein Data Bank and considered the coordinate location of all the hydrogen atoms for the numerical simulations performed using MATLAB. Some relevant information about the molecular spin system and parameters used for the simulations is listed in Table 1.

Figure 2. Simulations of projection-reconstruction method using a molecular phantom β-cyclodextrin.

(a) 3D visualization of hydrogen atoms in β-cyclodextrin molecule in a space filling representation. (b) Simulated spin noise spectra for two different gradient orientations. (c) Encoded signal matrix (some slices are omitted for visual clarity). (d) Reconstructed three dimensional image of a β-cyclodextrin molecule.

Table 1. Relevant parameters for imaging a molecular phantom β-cyclodextrin using NV spin based molecular structure microscope by projection-reconstruction method.

| Quantity | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phantom molecule | Molecule name | β-Cyclodextrin (Cycloheptaamylose) | |

| Chemical formula | C42H70O35 | ||

| Molecular weight | 1135 g/mol (1.14 kDa) | ||

| Molecular size | OD-15 Ǻ and ID- 6 Ǻ | ||

| Molecular shape | Toroidal | ||

| Proton density | 5.8 × 1028 m−3 (58 protons/nm3) | ||

| B0 Field | B0 Field | 500 Gauss | |

| 1H Larmor | 2128.5 kHz | ||

| Encoding | Gradient (magnetic tip) | 3 G/nm @ 100 nm | |

| Larmor frequency spread | 30.6 kHz | ||

| Spectral resolution (Δf) | 1.28 kHz | ||

| Signal B (r.m.s.) | 104–1H @ 7 nm19 | ~400 nT | |

| 70–1H @ 5 nm | ~94 nT | ||

| Signal acquisition time/point | Δf = 1.3 kHz | Δf = 30 kHz23 | |

| 1H using (XY8)n (SNR = 6)23 | 586 sec | 22 sec | |

| +DQC(XY8)n47 | 37 sec | 1.3 sec | |

| +Enhanced collection48,50 | 1 sec | 0.036 sec | |

| Projections | Distinct projections | θ (0°–180°) and φ (0°–180°) | |

| Total | 81 [9 × 9] | ||

| 3D structure acquisition time | ~33 minutes | ||

We virtually position the molecule in the proximity of an NV defect that is placed 5 nm beneath the surface of the diamond. At these close distances, the spin noise from hydrogen atoms is sensed by the NV spin19. We compute the fluctuating magnetic field amplitude (r.m.s.) produced by proton spins at the location of the NV spin by using the expression given by Rugar et al.23. The β-cyclodextrin molecule, when placed in the vicinity, produces a field of about 94 nT (r.m.s.), matching reported values19. We subject the molecule to the magnetic field gradients of 3 G/nm, and this produces spread in Larmor frequencies of 30.6 kHz for the hydrogen spins in the examined volume ( times molecule size). As explained before, we compute the Brms field produced by hydrogen spins in each isofield slice set by the spectral resolution ~1.3 kHz. The 1H spins in respective slices precess at their characteristic Larmor frequencies, so the noise spectrum reveals spectral features containing information about spin density distribution along the gradient direction. We show the computed spin noise spectra (Brms vs. frequency shifts) from the β-cyclodextrin molecule representing two different gradient orientations in Fig. 2b.

times molecule size). As explained before, we compute the Brms field produced by hydrogen spins in each isofield slice set by the spectral resolution ~1.3 kHz. The 1H spins in respective slices precess at their characteristic Larmor frequencies, so the noise spectrum reveals spectral features containing information about spin density distribution along the gradient direction. We show the computed spin noise spectra (Brms vs. frequency shifts) from the β-cyclodextrin molecule representing two different gradient orientations in Fig. 2b.

For three-dimensional encoding and reconstruction, we considered 9 × 9 unique gradient orientations equispaced along different θ, φ angles. The spectral data are computed for every projection, converted to spatial units and stored in a 3D matrix. This signal matrix is shown in Fig. 2c as slices in the r, θ dimensions. We apply the reconstruction algorithm as explained above to get the spatial distribution of hydrogen atoms. The structure of the reconstructed molecule clearly reveals its characteristic toroidal shape (Fig. 2d). The quality of the image reconstruction depends on the number of distinct tip locations (or gradient orientations) used for encoding38. The simulations presented in Fig. 2 display the reconstruction quality achieved for a toroidal molecule, β-cyclodextrin, for a set of 81 measurements used for encoding and decoding. If we consider the signal acquisition time of 22 seconds reported for a single point spectral measurement23 and calculate the time needed for achieving desired spectral resolution (~1.3 kHz), it results in long averaging times. We note that the signal acquisition time dramatically reduces to ~1 second/point by using double-quantum magnetometry47 together with enhanced fluorescence collection48. In this case the complete image acquisition time becomes approximately 33 minutes for the data set used here to reconstruct the molecular structure of an isolated β-cyclodextrin.

Discussion

The β-cyclodextrin molecule we have considered for simulations is a simple molecule, but it has a characteristic toroidal structure and is easy to visualize. The results clearly showed molecular-scale resolution and provided information about the structure. The structural details and achievable resolution depends on the following factors: The primary factor is the SNR obtainable when recording the noise spectra. Demonstrations using double quantum transitions (ms = −1  ms = +1) achieved high-fidelity spin manipulation49 and improved sensing47; applying those techniques could improve signal quality. The coherence time of the NV spin would be a factor in achieving better SNR23, but not the most decisive one for noise spectroscopy, as shown using correlation spectroscopy technique to achieve sub-kHz linewidths even in a shallow NV spin40. Spectral reconstruction using compressed sensing approach is expected to considerably speed-up sensing21,22,33,34. In addition to this, improved fluorescence collection efficiency from single NV defects can be achieved using nanofabricated pillars50, solid immersion lenses51 and patterned gratings48. The primary source of noise being the photon shot noise, boosting signal quality naturally increases the achievable resolution. Other techniques, such as dynamic nuclear polarization52, selective polarization transfer17,19,20,22, the quantum spin amplification mediated by a single external spin53, could give additional signal enhancements. Schemes employing ferromagnetic resonances to increase the range/sensitivity could provide other factors for resolution improvement54,55. The presented method is efficient for the reconstructing structural information and spins distribution at the nanoscale whenever it is possible to perform three-dimensional encoding. The encoding can be done either by using an external gradient source12,35,56 or by the field gradient created by NV in its vicinity20,57.

ms = +1) achieved high-fidelity spin manipulation49 and improved sensing47; applying those techniques could improve signal quality. The coherence time of the NV spin would be a factor in achieving better SNR23, but not the most decisive one for noise spectroscopy, as shown using correlation spectroscopy technique to achieve sub-kHz linewidths even in a shallow NV spin40. Spectral reconstruction using compressed sensing approach is expected to considerably speed-up sensing21,22,33,34. In addition to this, improved fluorescence collection efficiency from single NV defects can be achieved using nanofabricated pillars50, solid immersion lenses51 and patterned gratings48. The primary source of noise being the photon shot noise, boosting signal quality naturally increases the achievable resolution. Other techniques, such as dynamic nuclear polarization52, selective polarization transfer17,19,20,22, the quantum spin amplification mediated by a single external spin53, could give additional signal enhancements. Schemes employing ferromagnetic resonances to increase the range/sensitivity could provide other factors for resolution improvement54,55. The presented method is efficient for the reconstructing structural information and spins distribution at the nanoscale whenever it is possible to perform three-dimensional encoding. The encoding can be done either by using an external gradient source12,35,56 or by the field gradient created by NV in its vicinity20,57.

It is important to consider nuclear spins from water and other contaminants that form adherent monolayers on the surface of diamond4,19,23,24. The gradient encoding will register their spatial location appropriately. Upon reconstruction, this would result in a two-dimensional layer seemingly supporting the molecule of interest. This plane could come as a guide for visualization but can be removed by image processing if required. Homo-nuclear spin interactions cause line broadening and become a crucial factor when dealing with spins adsorbed on a surface. Unwanted spin interactions can be minimized by applying broadband, and robust decoupling methods such as phase modulated Lee-Goldburg (PMLG) sequences58.

The factors determining the achievable structural resolution are the magnetic field gradient, the SNR of spin signals, number of distinct perspectives and the spectral linewidth of the sample. It is practical to retrieve structural details with atomic resolutions by applying larger gradients, using SNR enhancing schemes, improving fluorescence collection, and using decoupling. We have considered reported parameters and demonstrated that our method can achieve molecular-scale resolution. Although continued progress clearly indicates that attaining atomic resolutions is within reach35,59. However, for many practical applications, it is sufficient to obtain molecular-scale structures that contain information relevant to biological processes. The key feature of the NV-based molecular structure microscope is the ability to retrieve the three-dimensional structural details of single isolated biomolecules under ambient conditions without restrictions on the sample quality or quantity. These will be very much useful for studying hard-to-crystallize proteins and intrinsically disordered proteins. A molecular structure microscope that has the potential to image molecules like prion proteins would be pivotal in understanding the structure, folding intermediates and ligand interactions. These insights would undoubtedly pave ways to understand the molecular mechanisms of diseases pathways and develop efficient therapeutic strategies for their treatment and prevention60.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lazariev, A. and Balasubramanian, G. A nitrogen-vacancy spin based molecular structure microscope using multiplexed projection reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 5, 14130; doi: 10.1038/srep14130 (2015).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the Max-Planck Society, Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kultur and DFG Research Center Nanoscale Microscopy and Molecular Physiology of the Brain.

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.L. and G.B. conceived the method. A.L. performed the numerical simulations and both authors analysed the results. G.B. wrote the paper with input from A.L. Both authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Abragam A. The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism. 82–83 (Clarendon Press, 1961). [Google Scholar]

- Wiesendanger R. Spin mapping at the nanoscale and atomic scale. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1495–1550 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Rugar D., Budakian R., Mamin H. J. & Chui B. W. Single spin detection by magnetic resonance force microscopy. Nature 430, 329–332 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen C. L., Poggio M., Mamin H. J., Rettner C. T. & Rugar D. Nanoscale magnetic resonance imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 1313–1317 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber A. et al. Scanning Confocal Optical Microscopy and Magnetic Resonance on Single Defect Centers. Science 276, 2012–2014 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Chernobrod B. M. & Berman G. P. Spin microscope based on optically detected magnetic resonance. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 14903 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Jelezko F., Gaebel T., Popa I., Gruber A. & Wrachtrup J. Observation of coherent oscillations in a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 076401 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress L. et al. Coherent dynamics of coupled electron and nuclear spin qubits in diamond. Science 314, 281–285 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. M. et al. High-sensitivity diamond magnetometer with nanoscale resolution. Nat. Phys. 4, 29 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Degen C. L. Scanning magnetic field microscope with a diamond single-spin sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 243111 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Maze J. R. et al. Nanoscale magnetic sensing with an individual electronic spin in diamond. Nature 455, 644–647 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian G. et al. Nanoscale imaging magnetometry with diamond spins under ambient conditions. Nature 455, 648–651 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen C. Nanoscale magnetometry: Microscopy with single spins. Nat Nano 3, 643–644 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian G. et al. Ultralong spin coherence time in isotopically engineered diamond. Nat. Mater. 8, 383–387 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maletinsky P. et al. A robust scanning diamond sensor for nanoscale imaging with single nitrogen-vacancy centres. Nat Nano 7, 320–324 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N., Hu J.-L., Ho S.-W., Wan J. T. K. & Liu R. B. Atomic-scale magnetometry of distant nuclear spin clusters via nitrogen-vacancy spin in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 242–246 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N. et al. Sensing single remote nuclear spins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 657–662 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamin H. J. et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with a nitrogen-vacancy spin sensor. Science 339, 557–60 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudacher T., Shi F., Pezzagna S. & Meijer J. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a (5-nanometer)3 sample volume. Science. 339, 561 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with single spin sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 5, 4703 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost M., Cai J. & Plenio M. ~B. Resolving single molecule structures with nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. ArXiv e-prints (2014) at <2014arXiv1407.6262K>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ajoy A., Bissbort U., Lukin M. D., Walsworth R. L. & Cappellaro P. Atomic-Scale Nuclear Spin Imaging Using Quantum-Assisted Sensors in Diamond. Phys. Rev. X 5, 11001 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Rugar D. et al. Proton magnetic resonance imaging using a nitrogen–vacancy spin sensor. Nat Nano 10, 120–124 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häberle T. et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic imaging with chemical contrast. Nat Nano 10, 125–128 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVience S. J. et al. Nanoscale NMR spectroscopy and imaging of multiple nuclear species. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 129–134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan L. et al. Decoherence imaging of spin ensembles using a scanning single-electron spin in diamond. Sci. Rep. 5, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti F. & Dobson C. M. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 333–366 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldherr G. et al. High dynamic range magnetometry with a single nuclear spin in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 105–108 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusran N. M., Momeen M. U. & Dutt M. V. G. High-dynamic-range magnetometry with a single electronic spin in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 109–113 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs G. D., Dobrovitski V. V., Toyli D. M., Heremans F. J. & Awschalom D. D. Gigahertz dynamics of a strongly driven single quantum spin. Science 326, 1520–1522 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loretz M., Rosskopf T. & Degen C. L. Radio-Frequency Magnetometry Using a Single Electron Spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 017602 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraoui A. et al. High-resolution correlation spectroscopy of 13C spins near a nitrogen-vacancy centre in diamond. Nat Commun 4, 1651 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A., Magesan E., Yum H. N. & Cappellaro P. Time-resolved magnetic sensing with electronic spins in diamond. Nat. Commun. 5, 3141 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puentes G., Waldherr G., Neumann P., Balasubramanian G. & Wrachtrup J. Efficient route to high-bandwidth nanoscale magnetometry using single spins in diamond. Sci. Rep. 4, 4677 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinolds M. S. et al. Subnanometre resolution in three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of individual dark spins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 279–84 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggio M. & Degen C. L. Force-detected nuclear magnetic resonance: recent advances and future challenges. Nanotechnology 21, 342001 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondin L. et al. Magnetometry with nitrogen-vacancy defects in diamond. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 56503 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller N. & Jerschow A. Nuclear spin noise imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103, 6790–6792 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cywiński Ł., Lutchyn R. M., Nave C. P. & Das Sarma S. How to enhance dephasing time in superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 77, 174509 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Kong X., Stark A., Du J., McGuinness L. P. & Jelezko F. Towards chemical structure resolution with nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. (2015) at <http://arxiv.org/abs/1506.05882>.

- Rondin L. et al. Stray-field imaging of magnetic vortices with a single diamond spin. Nat. Commun. 4, 2279 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häberle T., Schmid-Lorch D., Karrai K., Reinhard F. & Wrachtrup J. High-Dynamic-Range Imaging of Nanoscale Magnetic Fields Using Optimal Control of a Single Qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 170801 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofori-Okai B. K. et al. Spin properties of very shallow nitrogen vacancy defects in diamond. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 86, 81406 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Ielasi F. S. et al. Dip-Pen Nanolithography-Assisted Protein Crystallization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 154–157 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien H.-W., Kuo W.-H., Wang M.-J., Tsai S.-W. & Tsai W.-B. Tunable Micropatterned Substrates Based on Poly(dopamine) Deposition via Microcontact Printing. Langmuir 28, 5775–5782 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. True three‐dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance imaging by Fourier reconstruction zeugmatography. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 1141 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Mamin H. J. et al. Multipulse double-quantum magnetometry with near-surface nitrogen– vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 30803 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. et al. Three megahertz photon collection rate from an NV center with millisecond spin coherence. 6 (2014) at <http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.3068>.

- Arroyo-Camejo S., Lazariev A., Hell S. W. & Balasubramanian G. Room temperature high-fidelity holonomic single-qubit gate on a solid-state spin. Nat Commun 5, (2014). 10.1038/ncomms5870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babinec T. M. et al. A diamond nanowire single-photon source. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5 195–199 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildanger D. et al. Solid immersion facilitates fluorescence microscopy with nanometer resolution and sub-angstrom emitter localization. Adv. Mater. 24, OP309– 13 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London P. et al. Detecting and polarizing nuclear spins with nuclear double resonance on a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, (2013). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.067601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffry M., Gauger E. M., Morton J. J. L. & Benjamin S. C. Proposed Spin Amplification for Magnetic Sensors Employing Crystal Defects. Phys. Rev. B 107, 1–5 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe C. S. et al. Off-resonant manipulation of spins in diamond via precessing magnetization of a proximal ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 89, 180406 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Trifunovic L. et al. High-efficiency resonant amplification of weak magnetic fields for single spin magnetometry. 11 (2014). at http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shin C. et al. Sub-optical resolution of single spins using magnetic resonance imaging at room temperature in diamond. in Journal of Luminescence 130, 1635–1645 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- London P., Balasubramanian P., Naydenov B., McGuinness L. P. & Jelezko F. Strong driving of a single spin using arbitrarily polarized fields. Phys. Rev. A 90, 12302 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov E., Madhu P. K. & Vega S. High-resolution proton solid-state NMR spectroscopy by phase-modulated Lee-Goldburg experiment. Chem. Phys. Lett. 314, 443–450 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Shi F. et al. Single-protein spin resonance spectroscopy under ambient conditions. Sci. 347, 1135–1138 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F. U., Bracher A. & Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475, 324–332 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]