Contraceptive effectiveness is the leading characteristic for most women when choosing a method, but they often are not well informed about effectiveness of methods. Because of the serious consequences of “misinformed choice,” counseling should proactively discuss the most effective methods—long-acting reversible contraceptives and permanent methods—using the WHO tiered-effectiveness model.

Contraceptive effectiveness is the leading characteristic for most women when choosing a method, but they often are not well informed about effectiveness of methods. Because of the serious consequences of “misinformed choice,” counseling should proactively discuss the most effective methods—long-acting reversible contraceptives and permanent methods—using the WHO tiered-effectiveness model.

Improving access to long-acting, reversible methods of contraception (LARCs)—which provide highly effective, long-term, and easy-to-use protection against unintended pregnancy—is of crucial importance to the lives of countless individual women. Yet, among family planning experts, consensus remains elusive on the important issue of whether and how client counseling should emphasize this top tier of highly effective contraceptive methods. Research consistently shows women believe effectiveness is one of the most important factors—usually the most important factor—when choosing a contraceptive method,1 but accurate knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness remains poor.2

In this paper, we argue for proactive counseling based on the World Health Organization (WHO) tiered-effectiveness chart that begins with the relative effectiveness of various methods as a way to provide truly informed choice. All contraceptives are not created equal. Counseling that does not focus on effectiveness can lead to “misinformed choice,” which may undermine rights-based approaches.

RIGHTS-BASED FAMILY PLANNING

Recent WHO guidance, summarizing findings of a technical consensus meeting on contraceptive choice and human rights, advises programs on how to ensure human rights are respected and protected when services are scaled-up to reduce unmet need for family planning.3 This seminal document was reinforced and extended through a new conceptual framework for human rights-based family planning.4,5

The guidance was in part a reaction to civil society concerns about the ambitious, numerical goals of the Family Planning 2020 (FP2020) initiative, launched in London in 2012, which aims to extend modern contraceptive access to 120 million additional clients by 2020.6 In addition, this new series of publications also builds upon the international family planning community’s nearly 50-year history of commitment to voluntarism and promoting clients’ right to free choice in family planning.3 This rights-based message was affirmed at international population conferences such as the landmark International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994 and in a variety of reproductive health and rights frameworks adopted by normative bodies before and since.

Taken together, the new documents about rights-based family planning are an important reminder of the need for voluntary, coercion-free contraceptive services. Those committed to the sexual and reproductive health field should have these values at their core.

IMPACT OF LARCS

The renewed focus on rights-based family planning coincides with emerging findings from a variety of recent programs in both developed7,8 and developing9-13 countries to increase access to LARCs. In the most well known of these, the St. Louis CHOICE study, thousands of women were offered free, same-day contraceptive services and followed for up to 3 years to document reproductive health and other outcomes.7 Given availability of free contraception, 70% to 75% of women (including teens) chose LARCs,14,15 and both continuation and satisfaction were significantly higher among LARC users than non-LARC users.16 Non-LARC users in St. Louis were 20 times more likely to become pregnant in the next 3 years than LARC users.14 The powerful results from CHOICE have been a clarion call for the importance of making LARCs widely available in family planning programs.

In the large CHOICE study, in which 70%–75% of women chose LARCs, continuation and satisfaction were higher, and pregnancy rates much lower, among LARC vs. non-LARC users.

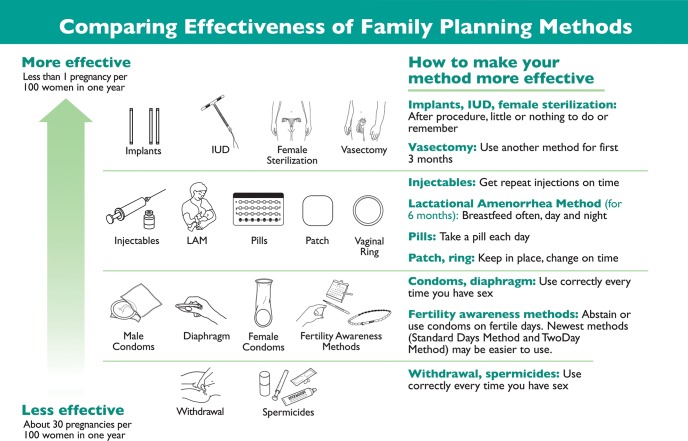

The CHOICE program offered a wide variety of methods and actively counseled clients about methods using the gradient of WHO’s “tiered” contraceptive effectiveness chart (Figure 1). Trained counselors described the full range of contraceptive methods and used internationally accepted counseling methods and tools, such as GATHER,20 to provide personalized counseling based on clients’ reproductive health needs.21 Within this framework of client-centered counseling, providers proactively spoke first about and emphasized the LARC methods of intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants in the highest tier of contraceptive effectiveness. This counseling approach was dubbed “LARC-first.”22

FIGURE 1.

World Health Organization Model of Tiered Contraceptive Effectiveness

BALANCING REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE AND TIERED COUNSELING

While the response to these programs has been overwhelmingly positive, some observers have begun a constructive dialogue about the potential pitfalls of embracing “LARC-first” without also emphasizing the necessary rights-based framework.23-25 They rightfully caution that in some situations tiered counseling could become too directive, or perhaps even coercive. This is especially worrisome in dealing with more vulnerable populations. We agree with these authors that the answer lies in striking a “delicate balance.”25 In particular, we support the position that “reproductive justice would enable women to access and use LARC if they wish to, but also to dispense with LARC and/or have LARC methods removed if they wish to.”24

Providers must strike a delicate balance between embracing “LARC-first” counseling while emphasizing reproductive rights.

Clinicians should not and, indeed, have no need to “push” LARCs. Evidence shows that when LARCs are available and affordable, most clients, if fully informed about effectiveness and relevant method characteristics, will choose them of their own accord.7-11 On the other hand, we disagree with the notion that other method characteristics should a priori be on par with that of effectiveness. In our view, the effectiveness of any contraceptive method is its paramount characteristic, and counseling that does not use WHO tiers (with the most effective methods discussed proactively) fails to meets the true needs and desires of the majority of women.

OUR PREMISES: CLIENT AUTONOMY, SAFETY, AND ACCURATE INFORMATION

We take as given the new WHO guidance (excerpted below), highlighting the paramount importance of client autonomy in decision making3(p.19):

Respecting autonomy in decision-making requires that any counselling, advice or information that is provided by health workers or other support staff should be non-directive, enabling individuals to make decisions that are best for themselves. People should be able to choose their preferred method of contraception, taking into consideration their own health and social needs.

We also take safety as a given, assuming that the global regulatory framework properly ensures the safety of modern contraceptives and, for the purpose of this paper, that the appropriate methods are safely provided to, and safely used by, clients.

Finally, we assume a right to non-directive counseling that conveys accurate information, including information about effectiveness and likelihood of pregnancy. This right is also emphasized in the new WHO guidance (excerpted below),3(p.19) as well as in earlier international conventions and covenants26,27:

Individuals have the right to be fully informed by appropriately trained personnel. Health-care providers have the responsibility to convey accurate, clear information, using language and methods that can be readily understood by the client, together with proper, non-coercive counselling, in order to facilitate full, free and informed decision-making. … The information provided to people so that they can make an informed choice about contraception should emphasize the advantages and disadvantages, the health benefits, risks and side-effects, and should enable comparison of various contraceptive methods. Censoring, withholding or intentionally misrepresenting information about contraception can put health and basic human rights in jeopardy.

EFFECTIVENESS AND OTHER METHOD CHARACTERISTICS

Research consistently shows women believe effectiveness is one of the most important factors when choosing a contraceptive method28-30; in many studies, effectiveness is mentioned as most important by a clear majority of women.1,17,31-33 Issues of side effects, the ability to use the method covertly, or the ability to control initiation and/or cessation of use are also important to women and should always be discussed. In some situations, they may “trump” effectiveness for certain women. However, to ensure that decision making is based on accurate information, effectiveness should be the fundamental starting point in describing methods for women seeking contraceptive services.

Effectiveness is one of the most important factors, and indeed often the most important factor, when women choose a method.

Given the evidence of women’s stated preferences, the 20-fold increased protection from unintended pregnancy that LARCs can provide, as well as the reality that approximately 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion,34 proactive counseling using the WHO tiers is simple, common sense. Among the many who have come to agree with counseling about the most effective methods first are the American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.35-37 The AAP 2014 policy statement on contraception for adolescents encourages providers to counsel by “discussing the most effective contraceptive methods first.”35 Internationally, the highly regarded “Balanced Counseling Strategy,” developed by the Population Council, also makes use of WHO-tiered counseling. Users of this popular counseling tool first help the client rule out certain classes of methods, then are guided by the strategy’s algorithm to: (1) visually present the remaining methods in order of effectiveness, (2) fully explain the concept of effectiveness, and (3) counsel the client beginning with the most effective methods.38

COMPREHENSIVE COUNSELING

The WHO contraceptive effectiveness tiers are only one piece in a larger framework of comprehensive counseling that must include private, client-centered conversation about a woman’s reproductive needs and desires. WHO-tiered counseling should not be equated with directive counseling, and it does not assume that a woman should choose a LARC. Nor does it dismiss the side effects or other characteristics of any method. Rather, it should help a client put those characteristics in a perspective that includes contraceptive effectiveness and pregnancy risk.

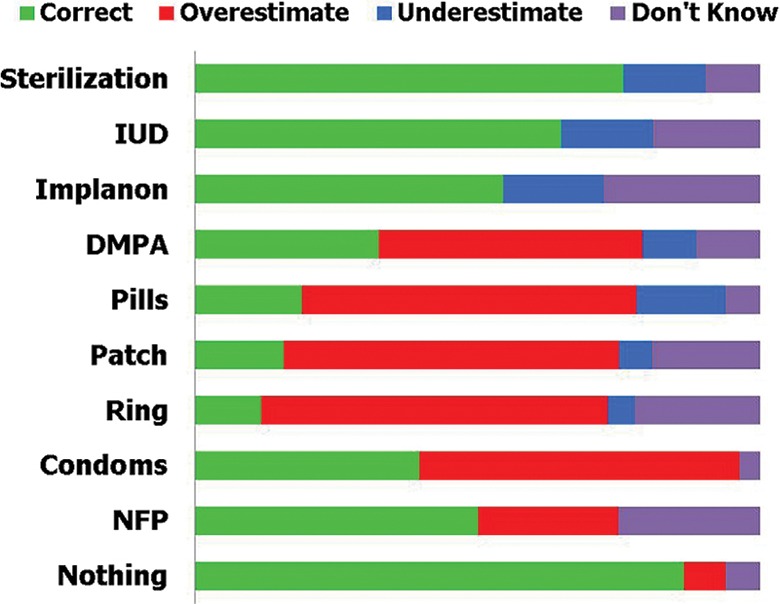

Conveying that risk, i.e., an understanding of the relative effectiveness of different methods, is challenging. Often, the absolute and relative effectiveness of different contraceptive methods are misunderstood by clients. For example, at enrollment, women in the St. Louis CHOICE study significantly overestimated the effectiveness of various non-LARC methods, while significantly underestimating the effectiveness of LARCs (Figure 2).2 Such misconceptions are widespread, leading to “misinformed choice” among women unless these misunderstandings are corrected by providers. While “misinformed choice” does not rise to the level of coercion, we agree with WHO3 that programs that do not fully and comprehensively educate women about method effectiveness and ensure that clients understand the differences between methods are not rights-based.

FIGURE 2.

Knowledge of Contraceptive Effectiveness Among Participants in the St. Louis CHOICE Study (N=4,144)

Abbreviations: DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUD, intrauterine device; NFP, natural family planning.

Source: Reprinted from Eisenberg et al.,2 with permission from Elsevier.

Providers have a responsibility to educate women about method effectiveness to help avoid “misinformed choice.”

NO LARCS IS NO EXCUSE

Another reason that providers may deemphasize LARCs during counseling is that long-acting methods may not be available or affordable in their setting. When this happens, we fail women by providing both counseling and service delivery that are not rights-based. Lack of access to LARCs remains a major problem both in the developed and the developing worlds. In low-resource regions, LARCs may not be available at all, or, where available in theory, may be unaffordable or impossible to access due to provider bias, outdated knowledge, or lack of training.39 Thus, millions of women are not receiving rights-based provision of family planning because they lack either information about and/or access to the full range of modern methods, and especially to LARCs. Our priority is increasing access to WHO tier-1 methods themselves, along with accurate education about their advantages and disadvantages.

CONCLUSION

For societies to reap the many benefits of family planning, both at the individual and macro levels, all methods of family planning, reversible and permanent, should be widely—indeed universally—available. Provision of these methods must include free choice, discontinuation on demand, and comprehensive counseling that proactively focuses on the WHO tiers of effectiveness. Until then, we are failing to accurately inform women with rights-based family planning programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge helpful comments by our colleagues Roy Jacobstein, Victoria Jennings, and Jeff Spieler, as well as those provided during peer review.

Competing Interests: None declared.

Peer Reviewed

Cite this article as: Stanback J, Steiner M, Dorflinger L, Solo J, Cates W. WHO tiered-effectiveness counseling is rights-based family planning. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(3):352-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00096.

REFERENCES

- 1.Snow R, García S, Kureshy N, et al. Attributes of contraceptive technology: women’s preferences in seven countries. Ravindran TKS, Berer M, Cottingham J, Beyond acceptability: users’ perspectives on contraception. London: Reproductive Health Matters for the World Health Organization; 1997. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/0953121003.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg DL, Secura GM, Madden TE, Allsworth JE, Zhao Q, et al. Knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):479.e1–e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: guidance and recommendations. Geneva: WHO; 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/human-rights-contraception/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardee K, Kumar J, Newman K, Bakamjian L, Harris S, Rodríguez M, et al. Voluntary, human rights-based family planning: a conceptual framework. Stud Fam Plann 2014;45(1):1–18. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar JL, Bakamjian S, Harris M, Rodriguez NYinger, Hardee K. 2014. Voluntary family planning programs that respect, protect, and fulfill human rights: conceptual framework users’ guide. Washington (DC): Futures Group; 2014. Available from: http://www.futuresgroup.com/files/publications/Voluntary_Rights-Based_FP_Users_Guide_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Family Planning 2020(FP2020) [Internet]. New York: United Nations Foundation; c2015. [cited 2015 Jul 7] Available from: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peipert JF, Madden T, Allsworth JE, Secura GM. Preventing unintended pregnancies by providing no-cost contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(6):1291–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricketts S, Klingler G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline in births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132. 10.1363/46e1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hubacher D, Olawo A, Manduku C, Kiarie J, Chen PL. Preventing unintended pregnancy among young women in Kenya: prospective cohort study to offer contraceptive implants. Contraception. 2012;86(5):511–517. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duvall S, Thurston S, Weinberger M, Nuccio O, Fuchs-Montgomery N. Scaling up delivery of contraceptive implants in sub-Saharan Africa: operational experiences of Marie Stopes International. Glob Health Sci Pract 2014;2(1):72–92. 10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curry DW, Rattan J, Huang S, Noznesky E. Delivering high-quality family planning services in crisis-affected settings II: results. Glob Health Sci Pract 2015;3(1):25–33. 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stunning popularity of LARCs with good access and quality: a major opportunity to meet family planning needs . Glob Health Sci Pract 2015;3(1):12–13. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neukom J, Chilambwe J, Mkandawire J, Mbewe RK, Hubacher D. Dedicated providers of long-acting reversible contraception: new approach in Zambia. Contraception. 2011;83(5):447–452. 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNicholas C, Madden T, Secura G, Peipert JF. The contraceptive CHOICE project round up: what we did and what we learned. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2014;57(4):635–643. 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mestad R, Secura G, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Zhao Q, Peipert JF. Acceptance of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods by adolescent participants in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Contraception. 2011;84(5):493–498. 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunloh DS, Casner T, Secura GM, Peipert JF, Madden T. Characteristics associated with discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception within the first 6 months of use. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(6):1214–1221. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000435452.86108.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner MJ, Trussell J, Mehta N, Condon S, Subramaniam S, Bourne D. Communicating contraceptive effectiveness: a randomized controlled trial to inform a World Health Organization family planning handbook. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195(1):85–91. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trussell J.Choosing a contraceptive: efficacy, safety, and personal considerations. Hatcher RA, Trussel J, Stewart F, Nelson AL, Cates W, Jr, Guest F, et al., editors Contraceptive technology, 19th revised edition New York: Arden Media; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO/RHR); Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH)/Center for Communication Programs (CCP) Family planning: a global handbook for providers. Baltimore (MD): CCP; 2007. Co-published by WHO; Available from: https://www.fphandbook.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinehart W, Rudy S, Drennan M. GATHER guide to counseling. Popul Rep J 1998;(48):1–31. Available from: https://www.k4health.org/toolkits/info-publications/gather-guide-counseling [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madden T, Mullersman JL, Omvig KJ, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Structured contraceptive counseling provided by the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Contraception. 2013;88(2):243–249. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LARC First [Internet] St. Louis (MO): Washington University in St. Louis; [cited 2015 Jul 7] Available from: http://www.larcfirst.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):171–175. 10.1363/46e1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JA. Celebration meets caution: LARC’s boons, potential busts, and the benefits of a reproductive justice approach. Contraception. 2014;89(4):237–241. 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gold RB. Guarding against coercion while ensuring access: a delicate balance. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2014;17(3):8–14. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/gpr/17/3/gpr170308.html [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) General comment no. 14 (2000): the right to the highest attainable standard of health (article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights). Geneva: United Nations Economic and Social Council; 2000. Available from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838d0.html [Google Scholar]

- 27.United Nations (UN) General recommendation 24 (twentieth session): article 12 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women--women and health. In: Report of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, Fifty-fourth session of the General Assembly, Supplement No. 38. New York: UN; 1999. Available from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/reports/21report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez LM, Steiner M, Grimes DA, Hilgenberg D, Schulz KF. Strategies for communicating contraceptive effectiveness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD006964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heise LL. Beyond acceptability: reorienting research on contraceptive choice. Ravindran TKS, Berer M, Cottingham J, Beyond acceptability: users’ perspectives on contraception. London: Reproductive Health Matters for the World Health Organization; 1997. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/0953121003.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh J. Contraceptive choices: supporting effective use of methods. Ravindran TKS, Berer M, Cottingham J, Beyond acceptability: users’ perspectives on contraception. London: Reproductive Health Matters for the World Health Organization; 1997. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/0953121003.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiner M, Dalebout S, Condon S, Dominik R, Trussell J. Understanding risk: a randomized controlled trial of communicating contraceptive effectiveness. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102(4):709–717. 10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tolley EE, McKenna K, Mackenzie C, Ngabo F, Munyambanza E, Arcara J, et al. Preferences for a potential longer-acting injectable contraceptive: perspectives from women, providers, and policy makers in Kenya and Rwanda. Glob Health Sci Pract 2014;2(2):182–94. 10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amin R. Choice of contraceptive method among females attending family planning center in Hayat Abad Medical Complex, Peshawar. J Pak Med Assoc 2012;62(10):1023–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darroch JE, Sedgh G, Ball H. Contraceptive technologies: responding to women’s needs. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2011. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/Contraceptive-Technologies.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.Committee on Adolescence . Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1244–e1256. 10.1542/peds.2014-2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice; Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group . Increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 450. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(6):1434–1438. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romero L, Pazol K, Warner L, Gavin L, Moskosky S, Besera G, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: trends in use of long-acting contraception among teens aged 15-19 seeking contraceptive services--United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(13):363–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.León FR, Vernon R, Martin A, Bruce L. The balanced counseling strategy: a toolkit for family planning service providers. Washington (DC): Population Council; 2008. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/research/the-balanced-counseling-strategy-a-toolkit-for-family-planning-service3 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell M, Sahin-Hodoglugil NN, Potts M. Barriers to fertility regulation: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann 2006;37(2):87–98. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2006.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]