Abstract

AT2433 from Actinomadura melliaura is an indolocarbazole antitumor antibiotic structurally distinguished by its unique aminodideoxypentose-containing disaccharide moiety. The corresponding sugar nucleotide-based biosynthetic pathway for this unusual sugar derives from comparative genomics where AtmS13 has been suggested as the contributing sugar aminotransferase (SAT). Determination of the AtmS13 X-ray structure at 1.50 Å resolution reveals it as a member of the aspartate aminotransferase fold type I (AAT-I). Structural comparisons of AtmS13 with homologous SATs that act upon similar substrates implicate potential active site residues that contribute to distinctions in sugar C5 (hexose versus pentose) and/or sugar C2 (deoxy versus hydroxyl) substrate specificity.

Keywords: carbohydrate, natural product, transamination, X-ray crystallography, indolocarbazole, sugar nucleotide

Introduction

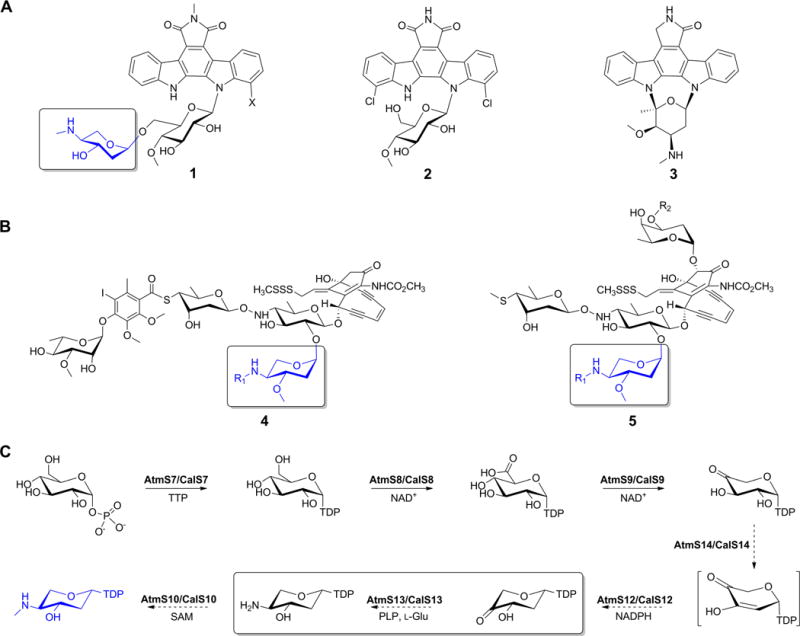

Functionalized deoxysugars appended to natural products are often critical to the given metabolite’s specificity on a tissue-, cellular-, and/or molecular-level where the corresponding functionalized deoxyhexoses are among the most diverse and best studied to date.1–6 In contrast, while functionalized deoxypentoses serve a similar purpose, the fundamentals of their biosynthesis remain largely uncharacterized. AT2433 (Figure 1A, 1) from Actinomadura melliaura is a model aminodeoxypentose-bearing member of the indolocarbazoles (exemplified also by 1; rebeccamycin, 2; and staurosporine, 3; Figure 1A). These actinomycete-derived alkaloids and potent inhibitors of topoisomerase I and kinases are relevant to anticancer, antitubercular, antimalarial and antiviral drug development.7–10 The AT2433 aminodideoxypentose uniquely influences the metabolite’s molecular mechanism and solubility.11–12 It is also notably found as part of structurally distinct naturally-occurring enediynes (calicheamicin, 4; and esperamicin, 5; Figure 1B). Comparative genomics of gene loci responsible for biosynthesis of the AT2433,13 calicheamicin,14 and rebeccamycin15–17 provided the basis for a proposed aminodideoxypentose biosynthetic pathway (Figure 1C)13. The gene cluster composition is consistent with previous esperamicin metabolic labeling studies and biosynthetic studies of Gram-negative exopolysaccharide aminopentoses. All these metabolites are involved in antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation and evasion of innate immunity.18–22 Subsequent biochemical characterization identified CalS8 as a TDP-α-D-glucose dehydrogenase23 and CalS9 as a TDP-α-D-glucuronic acid decarboxylase24 providing further support for this pathway. Of the remaining putative enzymes encoded by the AT2433 gene cluster, AtmS13 is the only apparent sugar aminotransferase and shares high sequence homology with CalS13 (62% identity and 76% similarity), the requisite calicheamicin TDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-α-D-glucose C4-aminotransferase.25,26 The putative AtmS13 substrate (TDP-4-keto-2,6-dideoxy-α-D-xylose) differs from the established CalS13 substrate (TDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-α-D-glucose) at C2 (H versus OH) and C5 (H versus CH2OH). Moreover, replacement of CalS13 with AtmS13 in standard CalS13 biochemical assays failed to provide turnover (unpublished data). In an effort to elucidate the molecular determinants that potentially contribute to the anticipated distinct sugar aminotransferase (SAT) TDP-hexose (CalS13) versus TDP-pentose (AtmS13) specificity, herein we report the X-ray structure determination at 1.50 Å resolution of AtmS13 with covalently attached cofactor, pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP). These studies reveal AtmS13 as a member of aspartate aminotransferase fold type I superfamily (AAT-I). A comparisons of the AtmS13 with structurally similar C4-SATs that act upon related substrates highlights potential active site features that may explain substrate preferences at C2 (H versus OH) and/or C5 (H versus CH2OH) as a basis for further SAT biochemical and/or engineering studies.

Figure 1.

(A) Indolocabazoles AT2433 (1, X = H or Cl), rebeccamycin (2) and staurosporine (3). (B) Aminopentose-containing enediynes calicheamicin (4), and esperamicin (5) where R1 = methyl, ethyl or isopropyl. (C) Proposed biosynthetic pathway of aminodideoxypentose shared by 1, 4 and 5. The aminodideoxypentose common to 1, 4 and 5 is highlighted in panels A and B (boxed and in blue) and the putative AtmS13 reaction is highlighted within the box in panel C.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

E. coli B834 (DE3) and BL21 (DE3)-Gold strain competent cells were purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The pET-28b E. coli expression vector and thrombin were purchased from Novagen (Madison, WI). Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technology (Coralville, IA). Pfu DNA polymerase was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Ni-NTA superflow column and gel filtration column HiLoad 16/600 were purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). Amicon Ultra® centrifugal filters were purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). Amicon Ultra® centrifugal filters were purchased from EMD Millipore (Merck, KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Crystal screen kits were purchased from Hampton Research (Aliso Viejo, CA), Molecular Dimensions (Altamonte Springs, FL), Rigaku (Seattle, WA) and Microlytic (Burlington, MA). Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal concentrators and L-selenomethionine (Se-Met) were purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA, USA) and Medicilon, Inc (Shanghai, China) respectively. All other chemicals were reagent grade or better and purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). X-ray diffraction data were collected at 21-ID-F beamline (LS-CAT) and at the 19-BM and 19-ID beamlines of the Structural Biology Center (SBC) at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) (Chicago, IL).

Gene Cloning and Expression, and Protein Purification

The full-length AtmS13 putative aminotransferase gene, atmS13, (NCBI accession, gi: 83320228; accession: ABC02793.1; also listed as atS13) was amplified by PCR from A. melliaura genomic DNA with KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase using the 5′- TACTTCCAATCCAATGCCATGATCCCCTTGTTCAAGGTGGC-3′ forward and 5′-TTATCCACTTCCAATGTTACCAGCCCGACCGGATGGT-3′ reverse primers. The amplification buffer was supplemented with betaine to a final 2.5 M concentration. The PCR products were purified, treated with T4 polymerase,27 cloned into the pMCSG68 vector according to ligation-independent procedures and the corresponding final clone confirmed via sequencing.28,29 This N-terminal TEV-cleavable StrepII/His6–AtmS13 dual tagged production vector was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)-Gold strain. The clones were tested in small scale for production, for Ni-NTA affinity, and for TEV-cleavage propensity. For large-scale protein production, bacterial culture was grown at 37 °C, at 190 rpm in 1 L of enriched M9 medium.30,31 When the OD600 reached ≈ 1, the culture was air-cooled to 4°C over a 60 min period and supplied with 90 mg L−1 of Se-Met and 25 mg L−1 of each of methionine biosynthetic inhibitory amino acids (L-valine, L-isoleucine, L-leucine, L-lysine, L-threonine, L-phenylalanine). Gene expression was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.5 mM and the cultures subsequently grown overnight at 18°C. For the production of native AtmS13, the atmS13 gene was ligated between NdeI and EcoRI of pET28a vector to produce AtmS13 with N-terminal His6-tag. The pET28a-AtmS13 construct was transformed into the E. coli BL21 (DE3) and overproduced in terrific broth media at 25 °C after the induction with 0.5 mM IPTG. Both, Se-Met and native AtmS13 were purified following same protocol. The cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer [500 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 20 mM imidazole, and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol]. Cells were disrupted by lysozyme treatment (1 mg mL−1) and sonication, and the insoluble cellular material was removed by centrifugation. The Se-Met AtmS13 was purified via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography using AKTAxpress system (GE Health Systems, Pittsburgh, PA) following a protocol with linear imidazole (10–250 mM) elution gradient. This was followed by the cleavage of the His6-tag of Se-Met AtmS13 using recombinant His6-tagged TEV protease at 4°C for 48 hours, with an additional Ni-NTA purification to remove the protease, uncut protein, and affinity tag. These procedures produced an AtmS13 with a Ser-Asn-Ala peptide preceding the N-terminal Met. The pure protein was concentrated using Amicon Ultra®-15 concentrators (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) in 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0 buffer, 250 mM NaCl, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Protein concentrations were determined from the absorbance at 280 nm using a molar absorption coefficient (ε280 = 62,910 M−1 cm−1) calculated by using the method developed by Gill and Hippel.32 The concentration of protein sample used for crystallization was 7.7 mg mL−1. Individual aliquots of purified protein were stored at −80°C until needed.

Protein Crystallization

Vapor-diffusion sitting drops containing 0.4 μL of protein with 1 mM pyridoxal 5′-phosphate hydrate and 0.4 μL of screening solution were set up in 96-well CrystalQuick plates (Greiner Bio-one, Monroe, NC, USA) over wells containing 140 μL screening solution using a Mosquito liquid dispenser (TTP Labtech, Cambridge, MA, USA). AtmS13 was screened against the commercially available crystallization suite, MCSG-1-4 (Microlytic Inc. MA, USA), at 4°C and 24°C. Crystals of Se-Met AtmS13 appeared in ~5% of conditions within 2 weeks at 24°C. The crystal from MCSG-1:21 (0.2 M MgCl2 and 20 w/v polyethylene glycol 3350) was selected for data collection using the addition of 25% glycerol as cryoprotectant. The crystals were cryoprotected by a brief transfer to the crystallization solution containing 15% glycerol and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Crystals of native AtmS13 appeared in 3.5 M sodium formate pH 7.0 within 5 days at 20°C and were flash frozen using the addition of 20% glycerol as cryoprotectant.

Data Collection and Structure Refinement

X-ray diffraction data of Se-Met AtmS13 was collected at the 19-BM and 19-ID beamlines of the SBC at the APS and that of native AtmS13 was collected at 21-ID-F (LS-CAT) in the APS at ANL (Chicago, IL). Data to 1.50 Å were collected with an X-ray wavelength of 0.9793 Å from the single crystal at the19-ID beamline. All data were processed and scaled using HKL3000.33 The structure of Se-Met AtmS13 was independently determined by SAD phasing with SHELX C/D/E, mlphare, and dm and initial automatic protein model building with resolve, buccaneer, or Arp/Warp as all implemented in the HKL3000 software package. Native AtmS13 was solved by molecular replacement using the Se-Met AtmS13 structure as the model. The initial models for both structures were further built in COOT34 and refined with the PHENIX35 and/or REFMAC36 in multiple iteration cycles until converged. The data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 1. The models of the AtmS13 structure (PDB entry: 4ZWV), with 1.5 Å resolution, were refined with anisotropic individual factors (except for water molecules). The PLP orientations in the active site were refined with group occupancy strategy and the final round of refinement was carried out by using translation/libration/screw (TLS) refinement with several TLS groups according to each structural situation. Analysis and validation of structures were performed with the aid of Molprobity38 and COOT34 validation tools. Figures were prepared using PyMOL.37

Table 1.

Summary of crystal parameters, data collection, and refinement statistics. Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Se-Met AtmS13 | Native AtmS13 | |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal parameters | ||

| Space group | C2 | R32:h |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | 204.1, 73.0, 58.6 90.0, 103.7, 90.0 |

223.1, 233.1, 460.9 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 |

| Data collection statistics | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97929 | 0.98000 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.4–1.50 | 30.0–3.00 |

| No. of reflections (measured/unique) | 560,589/130,016 | 978,914/95,972 |

| Completeness (%) | 97.8 (82.0) | 100.0 (99.0) |

| Rmerge* | 0.063 (0.392) | 0.138 (0.483) |

| Redundancy | 4.3 (3.1) | 10.2 (9.5) |

| Mean I/sigma (I) | 20.6 (3.7) | 7.6 (1.2) |

| CC1/2 | 0.99 (0.84) | 0.99 (0.51) |

| Refinement and model statistics | ||

| Rcryst§/Rfree¶ | 0.145/0.166 | 0.187/0.220 |

| Ligands RSCCa | 0.98 | 0.87 |

| RMSD bonds (Å) | 0.006 | 0.014 |

| RMSD angles (°) | 1.10 | 1.200 |

| B factor – protein/ligand/solvent (Å2) | 16.8/14.3/35.3 | 109.5/73.2/84.1 |

| No. of protein atoms | 6,271 | 20,446 |

| No. of waters | 1155 | 252 |

| No. of auxiliary molecules in the asymmetric unit | 2 LLP# | 1 PLP |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Favorable region | 99.0 | 95.0 |

| Additional allowed region | 1.0 | 4.7 |

| Outliers region | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| PDB | 4ZWV | 4XAU |

Rmerge = Σh Σi | Ii (h) – <I(h)>|/ΣhΣi Ii(h), where Ii(h) is the intensity of an individual measurement of the reflection and <I(h)> is the mean intensity of the reflection.

Rcryst = Σh ‖Fobs| – |Fcalc‖/Σh |Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure-factor amplitudes, respectively.

Rfree was calculated as Rcryst using 5.0 % of randomly selected unique reflections that were omitted from the structure refinement.

RSCC is the real-space correlation to electron density calculated by Phenix

LLP is the Lys187 PLP internal aldimine

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overall Structure

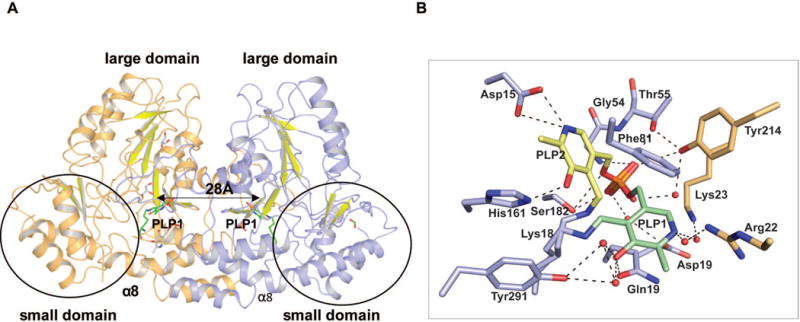

Crystal structures of Se-Met labeled and native AtmS13 with covalent PLP internal aldimine (named LLP in the coordinate file) were obtained in two different crystal forms at 1.50 Å and 3.00 Å resolution, respectively, by co-crystallizing AtmS13 in the presence of PLP (Table 1). The PLP adduct of Se-Met and native AtmS13 (PDB entries 4ZWV and 4XAU) belonged to C 2 and R 32:h space groups, respectively. The asymmetric unit contained two subunits bearing a large interaction surface area of ~4,600 Å2 representing the formation of a dimer. Since the root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) between the structures of two forms is 0.20 Å, the rest of the discussion in the text refers to the high-resolution structure of Se-Met AtmS13. Both subunits contain a covalent PLP internal aldimine with the side chain amine of the active site lysine residue Lys187 but adopt alternative poses (PLP1 and PLP2, Figure 2). The overall fold of AtmS13 belongs to the aspartate aminotransferase fold type I superfamily (AAT-I)4,39 and shares many structural characteristics with AAT-I members. Each dimer of AtmS13 contains two active sites spaced ~28 Å apart (based upon the distance between the pyridinium rings of bound PLP), with each monomer contributing critical residues to each active site (Figure 2A). Analogous to other AAT-I enzymes, AtmS13 has a conserved lysine (Lys187) that contributes to the PLP cofactor internal aldimine and a conserved general acid (Asp158) that is key to cofactor activation via PLP pyridinium nitrogen protonation. The overall architecture of each subunit comprises a N-terminal ‘large domain’ and a C-terminal ‘small domain’ (Figure 2A). The large domain contains a mixed β-sheet formed by seven β-strands (strand order β1, β7, β6, β5, β4, β2, β3) where β7 is antiparallel. This large β-sheet is flanked by α-helices on both sides. The C-terminal small domain is formed by a two-stranded antiparallel sheet (β-strands β8 and β9) surrounded by helices. The large and small domains are linked by an antiparallel β-hairpin comprised of 3 antiparallel beta-strands. The size of the 13 α-helices in the subunit range from 3 to 31 residues with the largest α-helix (α8) kinked and contributing to both domains (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Homodimer structure of AtmS13 (PDB 4ZWV). The two subunits are colored light orange and blue, respectively. The C-terminal, small domain is circled and the highlighted distance corresponds to distance between the respective active site bound cofactor pyridinium rings within the two monomers of the homodimer. (B) Residues involved in cofactor binding. The alternative PLP orientations (PLP1 and PLP2) are colored green and yellow, respectively. Active site residues are colored blue while the residues from the adjacent subunit contributing to the active site are colored orange.

Cofactor Binding Site

The cofactor-binding site is within a deep cleft in the interior of the active site of each monomer at the two far ends of the length of the dimer interface with two distinct orientation of PLP per monomer observed; both as an internal aldimine with Lys187 (PLP1 colored green and PLP2 colored yellow in Figure 2B). The PLP1 and PLP2 sites have 50% occupancy and similar B-factors (14.2 and 14.3) where the PLP phosphate moieties of both occupy the same position but the respective PLP pyridinium ring orientations differ by roughly 120° (Figure 2B). Of these two orientations in AtmS13, PLP2 is consistent with the PLP orientation in other structurally characterized SATs containing bound PLP. The former involve π-stacking of the pyridinium ring with Phe81. For the latter, the PLP C5 hydroxyl hydrogen bonds with His161 and the cofactor N1 pyridinium ring nitrogen is anchored by a salt bridge with the conserved general acid (Asp158) (Figure 2B).39 The phosphate group of the cofactor orients toward to the dimer interface and is held in place by several direct hydrogen bonding interactions. These involve the backbone amides of Gly54 and Thr55, the side chain hydroxyls Thr55 and Ser182 and the side chain hydroxyl of Tyr214 from the adjacent subunit (Figure 2B). The phosphate group of the cofactor also makes several water mediated interactions. These include the side chain carboxylates of Asp193 and side chain hydroxyl of Tyr214 from the adjacent subunit (colored orange in Figure 2B).

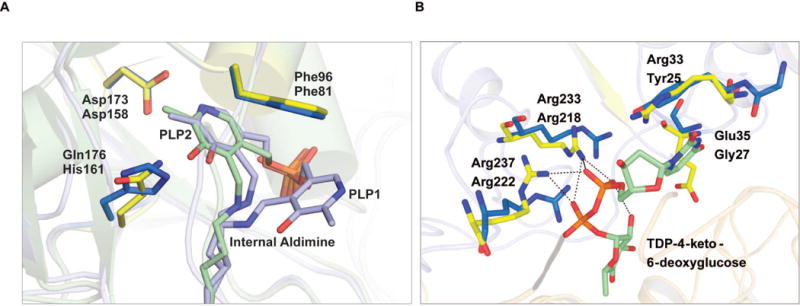

Comparison with CalS13

The structure of the biochemically characterized SAT (CalS13) involved in calicheamicin aminohexose biosynthesis was recently solved in ternary complex with PLP and TDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-α-D-glucose (PDB entry 4ZAS, Wang et. al. submitted). An overlay of the AtmS13 and CalS13 structures resulted in a root mean square deviation of 0.83 Å between the two structures. Upon analysis of the the active site of AtmS13 and CalS13, the key PLP interacting residues are largely conserved, a minor exception being the PLP C5 hydroxyl hydrogen bond partner AtmS13 His161 is replaced by CalS13 Gln176 (Figure 3A). Comparision of an AtmS13 TDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-α-D-glucose docked model with the CalS13 ternary complex reveals similar conservation of the arginine residues (Arg218/Arg222 and Arg233/Arg237 in AtmS13 and CalS13, respectively) responsible for binding the nucleotide sugar pyrophosphate but a slight variation in the residue that stacks over the thymidine ring (Arg33 in CalS13, Tyr25 in AtmS13) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Comparison of active site residues of AtmS13 with CalS13. (A) PLP binding site where the internal aldimine belonging to AtmS13 and CalS13 are colored blue and green, respectively. AtmS13 and CalS13 residues are colored marine blue and yellow, respectively. (B) Sugar nucleotide binding site (AtmS13 residues, marine blue; CalS13 residues, yellow; sugar nucleotide, green with pyrophosphate linkage in orange).

Interestingly, few ketosugar-specific interactions are observed in the CalS13 ternary complex or the AtmS13 docked model. Specifically, the single water-mediated hydrogen bonding interaction of the CalS13 side chain carboxylate of Glu35 with the substrate sugar hydroxyl is absent in AtmS13 (Gly27) (Figure 3B). This same position is occupied by Asn49 in S. venezuelae DesI (PDB entry 2PO3),40 a SAT that also utilizes TDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-α-D-glucose as a substrate, suggesting that specific sugar C2 contacts may be required for substrates containing a C2 hydroxyl. Of the other SATs that have been structurally studied [E. coli WecE, PDB entries 4ZAH and 4PIW, (Wang et. al. submitted); M. echinospora CalS13, PDB entry 4ZAS (Wang et. al. submitted); S. venezuelae DesV, PDB entry 2OGE;41 C. crescentus GDP-perosamine synthase, PDB entry 3DR7;42 T. thermosaccharolyticum QdtB, PDB entry 3FRK;43 S. typhimurium ArnB, PDB entry 1MDX;22,44 H. pylori PseC, PDB entry 2FNU;45 Campylobacter jejuni PglE, PDB entry 1O69; and P. aeruginosa WbpE, PDB entry 3NU746], ArnB is the only other pentose (UDP-4-keto-α-D-arabinose/xylose) C4-SAT. However, compared to AtmS13, ArnB-catalyzed transamination leads to inversion of C4-stereochemistry where the sugar substrate orientation in ArnB is flipped in the active site to enable stereochemical inversion. Therefore the putative C2 and/or C5 contacts in ArnB do not shed further light on the putative AtmS13/CalS13 substrate divergence.

In conclusion, this AtmS13 structural study adds an additional blueprint to the growing body of structural information regarding factors that define substrate specificity within C4-SATs. As such, this work sets the stage for future SAT biochemical and/or engineering studies designed to further probe SAT SAR.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants U01GM098248 (GNP), CA84374 (JST), GM094585 (AJ), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000117) and the Kresge Foundation. Use of the SBC beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences and Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team (LS-CAT) has been supported by Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

The authors report competing interests. JST is a co-founder of Centrose (Madison, WI).

References

- 1.Rupprath C, Schumacher T, Elling L. Nucleotide deoxysugars: Essential tools for the glycosylation engineering of novel bioactive compounds. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1637–1675. doi: 10.2174/0929867054367167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thibodeaux CJ, Melançon CE, 3rd, Liu HW. Natural-product sugar biosynthesis and enzymatic glycodiversification. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:9814–9859. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White-Phillip J, Thibodeaux CJ, Liu HW. Enzymatic synthesis of TDP-deoxysugars. Meth Enzymol. 2009;459:521–544. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04621-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S, Phillips GN, Jr, Thorson JS. The structural biology of enzymes involved in natural product glycosylation. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:1201–1237. doi: 10.1039/c2np20039b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin CI, McCarty RM, Liu HW. The biosynthesis of nitrogen-, sulfur-, and high-carbon chain-containing sugars. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:4377–4407. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35438a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elshahawi SI, Shaaban KA, Kharel MK, Thorson JS. A comprehensive review of glycosylated bacterial natural products. Chem Soc Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1039/c4cs00426d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matson JA, Claridge C, Bush JA, Titus J, Bradner WT, Doyle TW, Horan AC, Patel M. AT2433-A1, AT2433-A2, AT2433-B1, and AT2433-B2 novel antitumor antibiotic compounds produced by Actinomadura melliaura. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and biological properties. J Antibiot. 1989;42:1547–1555. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakano H, Ōmura S. Chemical biology of natural indolocarbazole products: 30 years since the discovery of staurosporine. J Antibiot. 2009;62:17–26. doi: 10.1038/ja.2008.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salas JA, Méndez C. Indolocarbazole antitumour compounds by combinatorial biosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Speck K, Magauer T. The chemistry of isoindole natural products. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2013;9:2048–2078. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Facompre M, Carrasco C, Colson P, Houssier C, Chisholm JD, Van Vranken DL, Bailly C. DNA binding and topoisomerase I poisoning activities of novel disaccharide indolocarbazoles. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1215–1227. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrasco C, Facompre M, Chisholm JD, Van Vranken DL, Wilson WD, Bailly C. DNA sequence recognition by the indolocarbazole antitumor antibiotic AT2433-B1 and its diastereoisomer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1774–1781. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.8.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao Q, Zhang C, Blanchard S, Thorson JS. Deciphering indolocarbazole and enediyne aminodideoxypentose biosynthesis through comparative genomics: Insights from the AT2433 biosynthetic locus. Chem Biol. 2006;13:733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahlert J, Shepard E, Lomovskaya N, Zazopoulos E, Staffa A, Bachmann BO, Huang K, Fonstein L, Czisny A, Whitwam RE, Farnet CM, Thorson JS. The calicheamicin gene cluster and its iterative type I enediyne PKS. Science. 2002;297:1173–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.1072105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sánchez C, Butovich IA, Braña AF, Rohr J, Méndez C, Salas JA. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the antitumor rebeccamycin: Characterization and generation of indolocarbazole derivatives. Chem Biol. 2002;9:519–31. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyun CG, Bililign T, Liao J, Thorson JS. The biosynthesis of indolocarbazoles in a heterologous E. coli host. Chembiochem. 2003;4:114–117. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200390004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onaka H, Taniguchi S, Igarashi Y, Furumai T. Characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster of rebeccamycin from Lechevalieria aerocolonigenes ATCC 39243. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:127–138. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam KS, Gustavson DR, Veitch JA, Forenza S. The effect of cerulenin on the production of esperamicin A1 by Actinomadura verrucosospora. J Ind Microbiol. 1993;12:99–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01569908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams GJ, Breazeale SD, Raetz CR, Naismith JH. Structure and function of both domains of ArnA, a dual function decarboxylase and a formyltransferase, involved in 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23000–23008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501534200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamad MA, Di Lorenzo F, Molinaro A, Valvano MA. Aminoarabinose is essential for lipopolysaccharide export and intrinsic antimicrobial peptide resistance in Burkholderia cenocepacia. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85:962–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laverty G, Gorman SP, Gilmore BF. Biomolecular Mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli biofilm formation. Pathogens. 2014;3:596–632. doi: 10.3390/pathogens3030596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee M, Sousa MC. Structural basis for substrate specificity in ArnB. A key enzyme in the polymyxin resistance pathway of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochem. 2014;53:796–805. doi: 10.1021/bi4015677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bililign T, Shepard EM, Ahlert J, Thorson JS. On the origin of deoxypentoses: Evidence to support a glucose progenitor in the biosynthesis of calicheamicin. Chembiochem. 2002;3:1143–1146. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20021104)3:11<1143::AID-CBIC1143>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simkhada D, Oh TJ, Pageni BB, Lee HC, Liou K, Sohng JK. Characterization of CalS9 in the biosynthesis of UDP-xylose and the production of xylosyl-attached hybrid compound. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;83:885–895. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1941-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao LS, Ahlert J, Xue YQ, Thorson JS, Sherman DH, Liu HW. Engineering a methymycin/pikromycin-calicheamicin hybrid: Construction of two new macrolides carrying a designed sugar moiety. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9881–9882. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh S, Peltier-Pain P, Tonelli M, Thorson JS. A general NMR-based strategy for the in situ characterization of sugar-nucleotide-dependent biosynthetic pathways. Org Lett. 2014;16:3220–3223. doi: 10.1021/ol501241a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dieckman L, Gu M, Stols L, Donnelly MI, Collart FR. High throughput methods for gene cloning and expression. Protein Expr Purif. 2002;25:1–7. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eschenfeldt WH, Lucy S, Millard CS, Joachimiak A, Mark ID. A family of LIC vectors for high-throughput cloning and purification of proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;498:105–115. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aslanidis C, de Jong PJ. Ligation-independent cloning of PCR products (LIC-PCR) Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6069–6074. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donnelly MI, Zhou M, Millard CS, Clancy S, Stols L, Eschenfeldt WH, Collart FR, Joachimiak A. An expression vector tailored for large-scale, high-throughput purification of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;47:446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim Y, Babnigg G, Jedrzejczak R, Eschenfeldt WH, Li H, Maltseva N, Hatzos-Skintges C, Gu M, Makowska-Grzyska M, Wu R, An H, Chhor G, Joachimiak A. High-throughput protein purification and quality assessment for crystallization. Methods. 2011;55:12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gill SC, von Hippel PH. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: The integration of data reduction and structure solution from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vagin AA, Steiner RA, Lebedev AA, Potterton L, McNicholas S, Long F, Murshudov GN. REFMAC5 dictionary: Organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2184–95. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7.4. Schrödinger: LLC; [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romo AJ, Liu HW. Mechanisms and structures of vitamin B(6)-dependent enzymes involved in deoxy sugar biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:1534–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burgie ES, Holden HM. Molecular architecture of DesI: A key enzyme in the biosynthesis of desosamine. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8999–9006. doi: 10.1021/bi700751d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgie ES, Thoden JB, Holden HM. Molecular architecture of DesV from Streptomyces venezuelae: A PLP-dependent transaminase involved in the biosynthesis of the unusual sugar desosamine. Protein Sci. 2007;16:887–896. doi: 10.1110/ps.062711007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cook PD, Holden HM. GDP-perosamine synthase: Structural analysis and production of a novel trideoxysugar. Biochem. 2008;47:2833–2840. doi: 10.1021/bi702430d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thoden JB, Schaffer C, Messner P, Holden HM. Structural analysis of QdtB, an aminotransferase required for the biosynthesis of dTDP-3-acetamido-3,6-dideoxy-alpha-D-glucose. Biochem. 2009;48:1553–1561. doi: 10.1021/bi8022015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noland BW, Newman JM, Hendle J, Badger J, Christopher JA, Tresser J, Buchanan MD, Wright TA, Rutter ME, Sanderson WE, Muller-Dieckmann HJ, Gajiwala KS, Buchanan SG. Structural studies of Salmonella typhimurium ArnB (PmrH) aminotransferase: A 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose lipopolysaccharide-modifying enzyme. Structure. 2002;10:1569–1580. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00879-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schoenhofen IC, Lunin VV, Julien JP, Li Y, Ajamian E, Matte A, Cygler M, Brisson JR, Aubry A, Logan SM, Bhatia S, Wakarchuk WW, Young NM. Structural and functional characterization of PseC, an aminotransferase involved in the biosynthesis of pseudaminic acid, an essential flagellar modification in Helicobacter pylori. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8907–8916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larkin A, Olivier NB, Imperiali B. Structural analysis of WbpE from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: A nucleotide sugar aminotransferase involved in O-antigen assembly. Biochem. 2010;49:7227–7237. doi: 10.1021/bi100805b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]