Abstract

Context:

Prenatal exposure to phthalates disrupts male sex development in rodents. In humans, the placental glycoprotein hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is required for male development, and may be a target of phthalate exposure.

Objective:

This study aimed to test the hypothesis that phthalates disrupt placental hCG differentially in males and females with consequences for sexually dimorphic genital development.

Design:

The Infant Development and Environment Study (TIDES) is a prospective birth cohort. Pregnant women were enrolled from 2010–2012 at four university hospitals.

Participants:

Participants were TIDES subjects (n = 541) for whom genital and phthalate measurements were available and who underwent prenatal serum screening in the first or second trimester.

Main Outcome Measures:

Outcomes included hCG levels in maternal serum in the first and second trimesters and anogenital distance (AGD), which is the distance from the anus to the genitals in male and female neonates.

Results:

Higher first-trimester urinary mono-n-butyl phthalate (MnBP; P = .01), monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP; P = .03), and mono-carboxy-isooctyl phthalate (P < .01) were associated with higher first-trimester hCG in women carrying female fetuses, and lower hCG in women carrying males. First-trimester hCG was positively correlated with the AGD z score in female neonates, and inversely correlated in males (P = 0.01). We measured significant associations of MnBP (P < .01), MBzP (P = .02), and mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP; P < .01) with AGD, after adjusting for sex differences. Approximately 52% (MnBP) and 25% (MEHP) of this association in males, and 78% in females (MBzP), could be attributed to the phthalate association with hCG.

Conclusions:

First-trimester hCG levels, normalized by fetal sex, may reflect sexually dimorphic action of phthalates on placental function and on genital development.

Phthalates, a class of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, are widely used in consumer products and are measurable in 95–100% of pregnant women in the United States (1). Although the concentrations of some phthalate esters have increased over the last 10 years, that of others have decreased (2). In rodents, phthalates alter androgen-sensitive development of male reproductive organs (3–5). It is assumed that maternal phthalates pass through the placenta to alter gene and protein expression directly within the fetal tissue.

This may not be the case in the human first trimester when the gestational sac (early placenta) is relatively impervious to maternal blood (6). Trophoblastic plugs block maternal blood flow into the intervillous spaces, thus maintaining the low oxygen environment necessary for normal development (7). Nonpersistent environmental chemicals such as phthalates likely enter the intervillous space through uterine gland secretions and plasma infiltrates, granting them greater access to the chorionic villi than to fetal circulation (6, 8). During this early stage in pregnancy, the placenta acts as a small factory for the synthesis and secretion of molecules such as human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (9), making it vulnerable to xenobiotics in maternal circulation. These secreted molecules may serve as an indicator of exposure-related perturbations within the fetal-placental compartment. This hypothesis represents a departure from the dominant model of fetal toxicology, which assumes that the placenta transports chemicals to the fetus and is neutral with regard to its own response.

hCG exhibits a “noncanonical” placental function in the first trimester, whereby it diffuses into the fetus and binds to the LH chorionic gonadotropin receptor (LHCGR) receptor in the fetal testis and stimulates the onset of T production, which is required for normal male sex development (10). Mutations in the LHCGR gene result in males born with hypogonadism and pseudohermaphrotism (11). Mothers who gave birth to cryptorchid males had approximately 20% lower circulating hCG in the second trimester of pregnancy vs age-matched normal males (12).

Circulating hCG (and corresponding mRNA transcripts) is approximately 10% higher in women carrying female vs male fetuses (13, 14). hCG may be altered by maternal exposures including diethylstilbesterol (15), chlorpyrifos (16), triclosan (17), and smoking (18). In an epidemiologic study and in follow-up experimental studies of the human trophoblast, expression of chorionic gonadotropin alpha, one of the genes that encodes hCG, was increased in females relative to males by mono-n-butyl phthalate (MnBP) (Adibi et al, manuscript submitted).

Prenatal exposures to certain phthalates (ie, di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate [DEHP], di-n-butyl phthalate, butylbenzyl phthalate) cause defects in the male rodent that include a shorter anogenital distance (AGD) at birth, higher incidence of hypospadias, cryptorchidism, and reduced fertility (3, 4). In The Infant Development and the Environment Study (TIDES), the parent study from which we conducted this analysis, which is the largest analysis to date (n = 750), there was a 4–5% decrement in AGD in male neonates born to mothers with high vs low prenatal urinary phthalate concentrations of DEHP metabolites (19). AGD is a sensitive marker of hormonal actions in pregnancy and is predictive of reproductive health and function over the life course (20). In rodents, phthalates inhibit T production. Experimental studies using human fetal testes explants have not recapitulated this effect (21–23). We hypothesize that the human placenta, through the production of hCG, may mediate this association (Supplemental Figure 1). The aim of the current analysis was to estimate associations between 1) prenatal phthalates and circulating first trimester placental hCG, and 2) circulating first-trimester placental hCG and AGD in male and female neonates.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

Pregnant women were enrolled onto TIDES between 2010 and 2012 at prenatal clinics in San Francisco, CA (University of California–San Francisco [UCSF]), Seattle, WA (University of Washington [UW]), Minneapolis, MN (University of Minnesota [UMN]), and Rochester, NY (University of Rochester Medical Center [URMC]). A woman was eligible if she was greater than 18 years of age, able to read and write in English, was less than 13 weeks pregnant, did not have a medically threatened pregnancy, and was planning to deliver in an eligible hospital. Details on the cohort and recruitment are published elsewhere (19). The institutional review boards at all participating institutions approved TIDES prior to study implementation. All subjects provided signed informed consent.

Prenatal serum screening

We accessed the prenatal medical record for subjects who underwent serum screening to detect fetal aneuploidy in the first or second trimesters. hCG is widely used clinically given that it is highly predictive of Down Syndrome and other fetal aneuploidies. UCSF samples were submitted to the California Genetic Disease Screening Program, and total hCG was measured by the AutoDELFIA time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay (PerkinElmer). At the other sites, samples were analyzed in University or private laboratories. For subjects at UW and UMN, hCG-β was measured by UniCel DxI 800 Immunoassay System (Beckman Coulter). For subjects at URMC, hCG-β was measured by UniCel DxI 600 Immunoassay System (Beckman Coulter). Even though hCG assays differed across TIDES sites, our measures of total hCG and hCG-β provide similar information. In a pilot study (N = 32), we measured a significant association of total hCG and hCG-β measured within the same first trimester serum samples (r = 0.61; P = .002). We therefore created a single z score for hCG levels across centers. The median ages at first- and second-trimester blood draws for hCG analysis were 12.1 and 16.7 weeks' gestation, respectively.

Urinary phthalate concentrations

Urine samples were collected in the first trimester in phthalate-free polypropylene cups. Collection and storage materials were also phthalate-free. Specific gravity was measured within 30 minutes using a hand-held refractometer (National Instrument Company, Inc.). The median gestational age at first trimester urine collection was 10.8 weeks. All samples of mothers of boys, and a subset of mothers of girls (N = 68), were analyzed at the Division of Laboratory Sciences, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The analytic method, described previously (24), involves enzymatic deconjugation of the metabolites from their glucuronidated form, automated online solid-phase extraction, separation with HPLC, and detection by isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. Samples from the remainder of mothers of girls were analyzed at the Environmental Health Laboratory at UW. After deconjugation, solid-phase extraction was coupled with reversed HPLC-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Details regarding the methods and quality control measures are outlined elsewhere (19, 24). Values below the limit of detection (LOD) were assigned the value of the LOD divided by the square root of 2 (25). Here we report results for eight phthalate monoester metabolites that were selected because they are all products of phase-I metabolism and are considered more bioactive than their parent compounds (26). By including metabolites that are products of phase II and more complex pathways of metabolism, we would potentially introduce greater confounding by interindividual differences in xenobiotic metabolism. The first category includes those decreasing in the urine of the U.S. population: MnBP, monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP), mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP), and monoethyl phthalate (MEP). The second category includes those that are increasing: mono-iso-butyl phthalate (MiBP), mono-carboxy-propyl phthalate (MCPP), mono-carboxy-isononyl phthalate (MCNP), and mono-carboxy-isooctyl phthalate (MCOP) (2). Urinary phthalate concentrations were specific-gravity adjusted as described elsewhere.

Anogenital distance

AGD is a measure of the distance from the anus to a genital landmark. In males the genital landmarks are 1) the anterior base of the penis where the penile tissue meets the pubic bone (AGD-AP) and 2) the base of the scrotum where the skin changes from rugated to smooth (AGD-AS). In females, the genital landmarks are 1) the anterior tip of the clitoral hood (AGD-AC) and 2) the base of the posterior fourchette where skin folds fuse (AGD-AF). Genital measurements were made on neonates within a few days of birth by a trained study staff (median age at examination, 1 d). Detailed methods describing AGD measurement are provided elsewhere (19, 27). All measurements were made with the infant lying on his/her back with the buttocks at the edge of a flat surface. An assistant held the legs in frog leg position at a 60–90° angle from the torso at the hip. Measurements in millimeters were made with the dial calipers (SPI Model 31–415-3, Style B). Each measurement was performed in triplicate and summarized as a mean. Length and weight were also measured following a study protocol, and used in adjustment of AGD for body size. In the data analysis, we treated AGD-AS in males and AGD-AF in females as parallel endpoints, and also AGD-AP in males and AGD-AC in females. One is the shorter and the other is the longer distance from the anus in both sexes.

Statistical analysis

Specific-gravity-adjusted urinary phthalate distributions were right skewed and transformed by a natural log transformation. To estimate male and female AGD within one model, we transformed the millimeter values to a z score scale, as has been done previously in studies of variation in sexually dimorphic development (28).

We examined multiple potential confounders including TIDES center, season, year, month of birth, maternal smoking, nutritional supplementation, chronic disease, stress, reproductive history, gynecologic disorders, endocrine disorders, and assisted reproduction in the current pregnancy. In these categories, we captured information on factors that could affect 1) phthalate exposure, metabolism and excretion; 2) placental hormone synthesis and secretion; and 3) fetal sex development. In addition, we assessed variables specifically related to phthalate measurement (laboratory, hour of urine sample) and AGD (age at examination, weight for length z score using World Health Organization standards) (19). Final selection of variables was based on our causal framework and directed acyclic graphs (29). We fit linear regression models to estimate the associations between 1) first trimester urinary phthalates and first- and second-trimester hCG, and 2) first- and second-trimester hCG and AGD. To control for interindividual differences in phthalate metabolism, we adjusted simultaneously for the monoester phthalate metabolites (MnBP, MBzP, MEHP, and MEP) and evaluated potential multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF). We considered VIFs greater than 10 to suggest a collinearity problem. Main effects of sex and phthalate/hCG and the sex by phthalate/hCG interaction terms were included in the model. When there was a significant interaction, we estimated percent changes in outcomes between the 90–10th and 25–75th percentiles of both exposures (phthalates, hCG), using stratified models with males and females, separately. We report here results for MCOP and MCNP as exploratory given that we had a large imbalance in the number of males (N = 172) and females (N = 50) due to limited resources to analyze the urine samples of women carrying females.

We used multivariate linear regression to estimate the relationship between phthalates and AGD z score in male and female neonates. To assess whether hCG mediates the effect of phthalates on AGD, we estimated the total vs direct association between phthalates and AGD. The direct association or controlled direct effect (CDE) captures the magnitude of the phthalates-AGD association that does not occur through hCG, and was estimated as described elsewhere (30, 31). A comparison of the coefficients for the total and direct association yields an estimate of the percentage of the total effect that could be blocked by a hypothetical block on hCG. To account for variation in both stages of the two-stage direct effect estimator, SEs, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained using the nonparametric percentile bootstrap based on 2000 resamples (32). All analyses were conducted with males and females combined. Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute) and in R (The R Project for Statistical Computing, r-project.org).

Results

Because not all women undergo prenatal serum screening, these data were available for 72% of the subjects in the parent cohort (47% in the first trimester and 35% in the second trimester with some overlap). The subset of subjects with hCG was not equally distributed across sites, compared with the parent study. It was similar to the parent cohort on demographics, reproductive history, and AGD characteristics (Table 1); although mean AGD-AF was significantly shorter by 0.5 mm (P = .05) in our subset than in the parent cohort (19). Phthalate metabolite concentrations in our subset did not differ and the proportions of subjects with detectable levels (64% for MEHP was the lowest and 100% for MCOP was the highest) were similar to the parent study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Subjects in The Infant Development and Environment Study (TIDES) who Underwent Prenatal Serum Screening in the First and/or Second Trimester

| UCSF | UMN | URMC | UWa | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 171 (32) | 112 (21) | 181 (33) | 77 (14) | 541 |

| Maternal age, y, Mean (se) | 34.8 (0.30) | 32.2 (0.45) | 27.0 (0.42) | 33.0 (0.54) | 31.4 (0.25) |

| Maternal race, N (%) | |||||

| White | 124 (73) | 89 (80) | 84 (46) | 61 (79) | 358 (66) |

| Black | 3 (2) | 4 (4) | 62 (34) | 4 (5) | 77 (14) |

| Asian | 27 (16) | 6 (5) | 2 (1) | 4 (5) | 39 (7) |

| Mixed | 5 (3) | 8 (7) | 10 (6) | 4 (5) | 27 (5) |

| Other | 12 (7) | 3 (3) | 23 (13) | 4 (5) | 42 (8) |

| Missing | 2 (2) | 2 | |||

| Hispanic ethnicity, N (%) | 19 (11) | 2 (2) | 26 (14) | 5 (6) | 52 (10) |

| Female baby, N (%) | 89 (52) | 52 (46) | 90 (50) | 44 (57) | 275 (51) |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, mean (se) | 23.8 (0.33) | 25.2 (0.51) | 28.2 (0.57) | 25.4 (0.71) | 25.8 (0.27) |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy weight, lb, Mean (se) | 142.2 (1.95) | 153.7 (3.51) | 164.7 (3.44) | 155.9 (4.23) | 154.0 (1.65) |

| Gravid, N (%) | 109 (64) | 56 (50) | 127 (70) | 49 (64) | 341 (63) |

| Nulliparous, N (%) | 98 (57) | 71 (63) | 90 (50) | 41 (53) | 300 (55) |

| Assisted reproduction, N (%) | 17 (10) | 11 (10) | 8 (4) | 4 (5) | 40 (7) |

| Household income, N (%) | |||||

| < $45 000 | 17 (10) | 22 (20) | 126 (69) | 12 (16) | 177 (33) |

| $45 000–75 000 | 17 (10) | 25 (21) | 21 (12) | 16 (21) | 78 (14) |

| >$75 000 | 137 (80) | 59 (53) | 25 (14) | 44 (57) | 265 (49) |

| Missing | 7 (6) | 9 (5) | 5 (6) | 21 (4) | |

| Gestational age at delivery, wk, Mean (se) | 39.1 (0.13) | 38.8 (0.17) | 38.6 (0.12) | 39.1 (0.18) | 38.9 (0.07) |

| Birthweight, kg, Mean (se) | 3.38 (0.04) | 3.41 (0.05) | 3.19 (0.04) | 3.41 (0.06) | 3.33 (0.02) |

| Anogenital distance: AS/AF, mm | |||||

| Male, Mean (se) | 25.5 (0.55) | 24.3 (0.51) | 23.9 (0.41) | 26.4 (1.04) | 24.8 (0.29) |

| Female, Mean (se) | 14.4 (0.34) | 16.0 (0.38) | 15.3 (0.27) | 18.0 (0.43) | 15.6 (0.19) |

| Anogenital distance: AP/AC, mm | |||||

| Male, Mean (se) | 50.9 (0.69) | 50.1 (0.64) | 47.9 (0.54) | 50.2 (1.58) | 49.6 (0.38) |

| Female, Mean (se) | 37.0 (0.46) | 36.4 (0.51) | 35.9 (0.39) | 36.9 (0.58) | 36.5 (0.24) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

UW subjects only contributed second trimester hCG values.

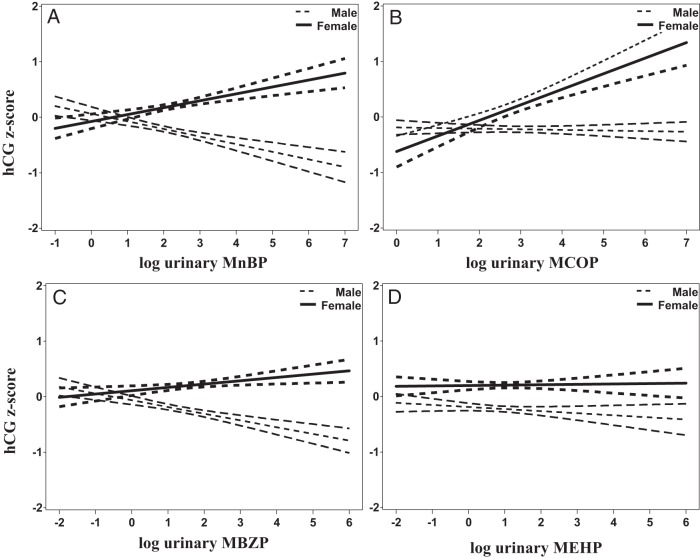

We detected significant associations of three phthalate metabolites (MnBP, MBzP, and MCOP) of the eight tested with hCG, after adjusting for sex differences (Table 2; Figure 1). The VIF in our models did not exceed 3. We estimated that hCG was 2.3-fold higher (MCOP), 3.9-fold higher (MnBP), and 4.2-fold higher (MBzP) in women carrying females at the 75th vs the 25th percentile. In women carrying males, hCG was lower by 0.7-fold (MCOP), 1.5-fold lower (MnBP), 1.5-fold lower (MBzP) at the 75th vs 25th percentile. As expected from previous reports, circulating hCG was significantly higher in women carrying females vs males (beta coefficient = 0.42; z score unit 95% CI, 0.22,–0.62) before and after adjustment for phthalates and other covariates. First-trimester urinary phthalate metabolites were not associated with second-trimester hCG levels.

Table 2.

Linear Associations of First Trimester Log Urinary Phthalate Concentrations and hCG z Scores in Women Carrying Female and Male Fetuses

| Group | N | Male, β (95% CI) | Female, β (95% CI) | Interaction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% C.I) | P Value | ||||

| Group 1 | |||||

| MnBP | 354 | −0.13 (−0.30–0.04) | 0.16 (−0.01–0.33) | 0.29 (0.07–0.51) | .01 |

| MBzP | 354 | −0.09 (−0.24–0.06) | 0.11 (−0.04–0.26) | 0.20 (0.02–0.38) | .03 |

| MEHP | 354 | −0.09 (−0.25–0.07) | −0.03 (−0.19–0.12) | 0.06 (−0.16–0.27) | .61 |

| MEP | 354 | 0.03 (−0.07–0.13) | −0.02 (−0.13–0.08) | −0.05 (−0.20–0.09) | .47 |

| Group 2 | |||||

| MiBP | 354 | −0.17 (−0.39–0.06) | 0.03 (−0.13–0.20) | 0.20 (−0.04–0.45) | .11 |

| MCPP | 354 | −0.04 (−0.15–0.07) | 0.01 (−0.10–0.12) | 0.05 (−0.10–0.20) | .52 |

| MCNP | 222 | −0.05 (−0.20–0.10) | 0.08 (−0.19–0.36) | 0.13 (−0.18–0.44) | .41 |

| MCOP | 222 | 0.03 (−0.08–0.14) | 0.38 (0.15–0.61) | 0.35 (0.10–0.60) | <.01 |

All models are adjusted for specific-gravity-adjusted log urinary phthalates, TIDES center, gestational age at the time of blood draw, hour of urine collection, maternal race, income, and weight in the first trimester. Group 1 includes those metabolites that are increasing in the U.S. population, and Group 2 includes those that are decreasing. Women carrying male fetuses are the referent.

Figure 1.

Adjusted linear associations of first trimester log urinary phthalate concentrations (specific gravity adjusted) with the hCG z score across three TIDES Centers. Predicted mean values and 95% CIs are shown with dotted lines for women carrying male fetuses, and with solid lines for women carrying female fetuses. A, MnBP; B, MCOP; C, MBzP; D, MEHP.

First-trimester hCG was directly associated with a shorter distance from the anus to scrotum in the male, and a longer distance from the anus to the fourchette in the female (P for sex by hCG interaction = .01; Table 3). This association was not seen for hCG and the longer AGD (anus to penis and anus to clitoris) in either males or females. Comparing hCG levels at the 25th vs the 75th percentiles, the anus-scrotum distance was 4.3% shorter in males, whereas the comparable anus-fourchette distance was 3.3% longer in females. Taking a more extreme but clinically relevant contrast of the 10th vs the 90th percentile, the estimates are much more pronounced with a 8.0% shorter distance in males and 6.0% longer distance in females. These associations were independent of phthalate levels.

Table 3.

Adjusted Linear Associations of hCG z Scores and Anogenital Distance z Scores in Male and Female Neonates

| N | Male, β (95% CI) | Female, β (95% CI) | Interaction (Male is Referent) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% C.I) | P Value | ||||

| First trimester | |||||

| AGD-scrotum/fourchettea | 349 | −0.12 (−0.28–0.03) | 0.13 (0.01–0.26) | 0.26 (0.06–0.46) | .01 |

| AGD-penis/clitorisb | 355 | −0.06 (−0.21–0.10) | 0.10 (−0.03–0.24) | 0.16 (−0.04–0.37) | .12 |

| Second trimester | |||||

| AGD-scrotum/fourchettec | 259 | −0.03 (−0.19–0.14) | −0.02 (−0.21–0.16) | 0.01 (−0.43–0.24) | .97 |

| AGD-penis/clitorisd | 258 | 0.03 (−0.14–0.19) | 0.01 (−0.18–0.10) | −0.02 (−0.25–0.22) | .87 |

All models are adjusted for TIDES center, gestational age at the time of blood draw, infant age at the time of the exam, maternal age, z score for weight for length, and log urinary phthalates (specific-gravity adjusted). Women carrying male fetuses are the referent.

Adjusted additionally for income, month of birth, calcium supplementation, and gamete intrafallopian transfer/zygote intrafallopian transfer (GIFT/ZIFT).

Adjusted additionally for history of diabetes, vitamin D supplementation, assisted reproductive technology (A.R.T.) and GIFT/ZIFT.

Adjusted additionally for history of chronic pain, history of thyroid disorders, and A.R.T.

Adjusted additionally for history of depression, folic acid supplementation, weight in the second trimester and GIFT/ZIFT.

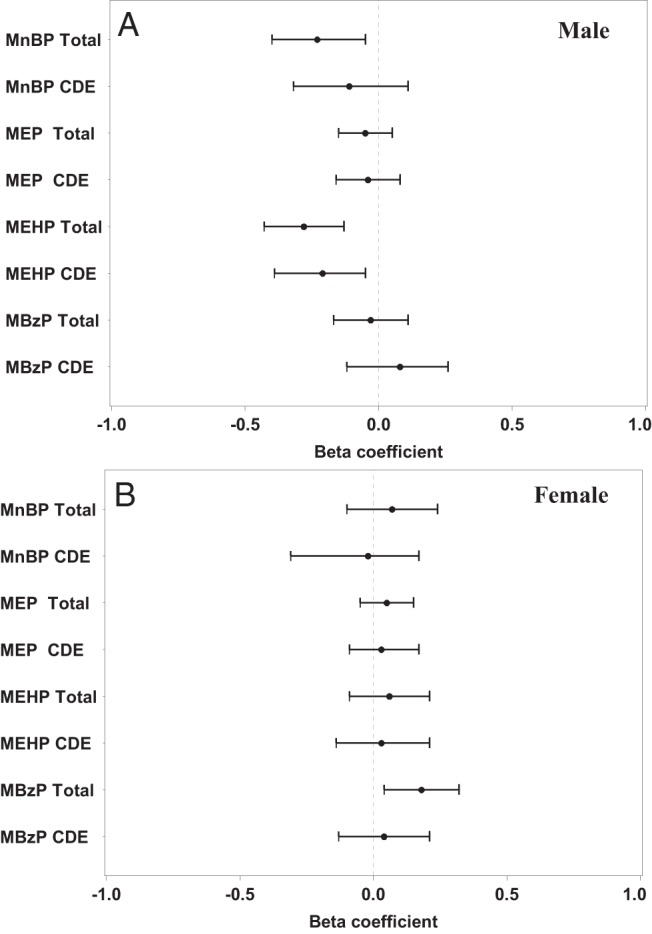

Of the eight urinary phthalate metabolites we examined, three were associated with a downward shift in the male anus-scrotum distance relative to female anus-fourchette distance: MnBP, MBzP, and MEHP (Table 4). These are similar to the results for the male reported for the full TIDES cohort. In contrast with the results from the parent study that were generated from stratified analyses of males and females, we detected significant associations of AGD with MnBP (stronger in male neonates) and MBzP (stronger in female neonates).

Table 4.

Linear Associations of First Trimester Log Urinary Phthalate Concentrations and Anogenital Distance (AGD-short) z Scores in Male and Female Neonates.

| Group | N | Male, β (95% CI) | Female, β (95% CI) | Interaction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

| Group 1 | |||||

| MnBPa | 349 | −0.23 (−0.40–−0.05) | 0.07 (−0.10–0.24) | 0.30 (0.09–0.51) | <.01 |

| MBzPb | 349 | −0.03 (−0.17–0.11) | 0.18 (0.04–0.32) | 0.21 (0.03–0.39) | .02 |

| MEHPc | 349 | −0.28 (−0.43–−0.13) | 0.06 (−0.09–0.21) | 0.34 (0.13–0.55) | <.01 |

| MEPd | 349 | −0.05 (−0.15–0.05) | 0.05 (−0.05–0.15) | 0.10 (−0.03–0.24) | .14 |

| Group 2 | |||||

| MiBPe | 349 | −0.15 (−0.37–0.07) | 0.06 (−0.11–0.22) | 0.21 (−0.03–0.45) | .08 |

| MCPPd | 349 | −0.04 (−0.15–0.07) | −0.01 (−0.11–0.09) | 0.03 (−0.11–0.17) | .71 |

| MCNPd | 219 | 0.09 (−0.05–0.23) | −0.06 (−0.32–0.20) | −0.15 (−0.44–0.15) | .33 |

| MCOPd | 219 | 0.08 (−0.03–0.19) | 0.09 (−0.15–0.32) | 0.01 (−0.24–0.25) | .95 |

All models are adjusted for log urinary phthalates (specific-gravity adjusted), baby sex, TIDES Center, hour of urine collection, infant age at time of exam, maternal age, maternal income, calcium supplementation, and z score for weight for length. Group 1 includes those metabolites that are increasing in the U.S. population, and Group 2 includes those that are decreasing. Women carrying male fetuses are the referent.

Adjusted additionally for month of birth and parity.

Adjusted additionally for year of birth, month of birth, and parity.

Adjusted additionally for month of birth.

Adjusted additionally for month of birth, parity.

Adjusted additionally for history of asthma.

For every log unit increase in MnBP and MEHP, male AGD decreased respectively by 0.23 (95% CI, −0.40–−0.05) and by 0.28 z score units (95% CI, −0.43–−0.13). For every log unit increase in MBzP, female AGD increased by 0.18 z score units (95% CI, 0.04–0.32) (Table 4). Part of these decreases and increases in AGD may be due to the effect of phthalates on hCG and the contribution of hCG to the formation of the genitals. The controlled direct effect (CDE) tells us how much (Figure 2). If we, for example, administered a hypothetical substance that completely blocked the effect of hCG, then MnBP would induce a nonsignificant 0.11 z score unit (95% CI, −0.32–−0.11) decrease in AGD, MEHP would induce a significant 0.21 decrease (95% CI, –0.39–−0.05) decrease in AGD. In female fetuses with a hypothetical block on hCG, MBzP would induce a nonsignificant 0.04 z score unit (95% CI, −0.13–0.21) increase in AGD. Our inference, therefore, is that hCG explained 52% (MnBP) and 25% (MEHP) of the phthalate association with male AGD. In females, hCG explained 78% of the association of MBzP with AGD.

Figure 2.

Forest plots of the beta coefficients, and their 95% CIs for the total phthalate effect on male and female AGD-AS/AF (total), and after blocking the CDE of human chorionic gonadotropin. The dotted line represents the null.

Discussion

We measured significant associations of first-trimester urinary concentrations of three phthalate metabolites with circulating levels of hCG that differed depending on whether the subject was carrying a male or a female. Higher first-trimester hCG was associated with longer AGD in female neonates, which signifies a masculinization effect (33), and shorter AGD in male neonates, which signifies reduced masculinization of the genitalia (20). A substantial portion of the phthalate association with AGD could be attributed to the phthalate association with hCG. We offer evidence that the effects of phthalates, and possibly other endocrine-disrupting compounds, on fetal development may occur by way of exposure-induced changes in hormone synthesis and secretion in the first-trimester placenta (Supplemental Figure 1). This opens new possibilities to isolate in time and space, and to more precisely measure the effects of endocrine-disrupting compounds on human fetal development.

hCG has a role in almost every physiologic process in pregnancy including implantation, angiogenesis, immune tolerance, and uterine quiescence (34). Our data support the function of hCG as a morphogen in the differentiation of the fetal testes (10). The second-trimester hCG measure was closer in time by one gestational month to birth and to the AGD measurement, yet we only detected a significant association between first-trimester hCG and AGD. This is consistent with the presence of the masculinization programming window between 8 and 12 weeks' gestation (35). The effects of endocrine disruption on fetal testes differentiation in the first trimester are more profound than effects on androgen receptor–mediated pathways later in pregnancy, or even later in postnatal life (35–37).

AGD is an established marker of in utero endocrine disruption (20), and it may also be a marker of fertility, hormonal status, and gonadal health in adulthood (33, 38, 39). In rodents, AGD at birth predicts subsequent reproductive health; however, it is unknown whether that holds true in humans (20). The shorter AGD measure (anus-scrotum, anus-fourchette) was significantly associated with hCG, and the longer AGD measure (anus-penis, anus-clitoris) was not. In the parent study, both measures of AGD in the male were correlated with phthalates and were correlated with each other (r = 0.65 in males; r = 0.47 in females) (19). The long and short forms of AGD may reflect different developmental processes, and the longer measure may be under the regulation of nonplacental or non-hCG placental factors. The differences in association may be due to greater measurement error in the long form of AGD (27).

In the parent study, only the DEHP metabolites (including MEHP) were significantly correlated with AGD (19). In this subset, MnBP, MBzP, and MCOP, but not MEHP, were correlated with placental hCG. However, we estimated that hCG contributed approximately 25% to the reduction in the anus to scrotum distance in males associated with MEHP. It is possible that the pharmacokinetics of MEHP differ such that it present at higher concentrations in maternal uterine tissues and therefore can access embryonic/fetal tissue earlier in development and at higher concentrations (ie, a direct effect and not hCG mediated). It is also possible that MEHP alters the secretion of a different, unmeasured placental molecule, other than hCG, with consequences for fetal testes differentiation and AGD. We hypothesize that the phthalate monoesters work through distinct cellular mechanisms and may have differential access to the chorionic villi where hCG synthesis takes place.

Median urinary concentrations of MnBP, MBzP, and MCOP were 1.5–3.5-fold higher than MEHP. If blood (internal dose) and urine (excreted dose) concentrations are correlated, then we might infer that access of the first trimester placenta to MEHP was limited. The median MnBP urinary concentration was 5-fold lower in this study compared with the earlier cohort study, which ended in 2006 (40), a trend that is consistent with an analysis of the U.S. population (2). Even at these reduced concentrations phthalates may interfere with human developmental pathways.

Several aspects of our model building are notable. Because our primary aim was to evaluate associations with sexual dimorphism in the fetal period, unlike previous work, we included males and females in all analyses. In addition, we simultaneously adjusted for multiple phthalates for the following reasons: 1) to control for between-person difference in metabolism and excretion in pregnancy, 2) to estimate the independent effects of the different metabolites, and 3) to more accurately reflect the physiologic reality of simultaneous exposure to multiple phthalates. Finally, in our model-building criteria, we considered a wide range of factors that could potentially be a common cause of the exposures and the outcomes. A strength of this analysis is that we were able to assess associations with two endpoints in males and females that are sex dependent and highly relevant to the fetal period in development: circulating hCG level and AGD at birth. These findings provide epidemiologic confirmation of an experimental finding (Adibi et al, manuscript submitted), and also confirmation at the level of the circulating protein of the same association with the corresponding mRNA. A limitation is that we had to rely on clinical measurements of hCG and therefore only were able to include half of the TIDES study population. Given the large variation in these exposures and outcomes, these analyses must be conducted in larger populations to achieve more robust estimates.

We measured an association of both hCG and a phthalate with the female AGD-AF, indicating that this type of endocrine disruption is relevant to female as well as male development. This merits special attention because previous studies have found few effects of phthalates on female reproductive development. It is unclear how small differences in AGD at birth may relate to children's long-term health and wellbeing. To further explore this question, sexually dimorphic anthropometrics and neurodevelopment will be assessed in this cohort at ages 3 and 6 years. We will continue to examine the degree to which placental hCG is correlated with sex-specific development later in childhood.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that placental hCG may be a target of prenatal phthalate exposure, and may explain up to 25–78% of the phthalate-induced variability in AGD. This represents a shift in the paradigm in how endocrine-disrupting exposures in the fetal environment can disrupt development. With increased understanding of these relationships, we may be able to offer new insights and methods to monitor early pregnancies for exposure-related shifts in development.

Acknowledgments

We thank the contributions of The Infant Development and the Environment Study (TIDES) Investigators Dr Sarah Janssen and Dr Lawrence Baskin at UCSF; the TIDES Research Staff at all four sites who helped to abstract the data; the prenatal screening laboratories including Sona Saha and Robert Currier at the Genetic Disease Screening Program of the California Department of Public Health for providing the hCG data, and Ilpo Huhtaniemi and Ulf-Håkan Stenman who mentored J.J.A. on aspects of hCG; and Susan Fisher who has mentored J.J.A. on aspects of placental biology. The Department of Epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh provided funds and a supportive environment for J.J.A. to pursue this project.

This work was supported by Grants No. NIEHS 5K99ES017780-02 (J.J.A.), NIEHS R00ES017780-06 (J.J.A.), R01ES016863-04 (S.H.S.), and R01 ES016863-02S4 (S.H.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AGD

- anogenital distance

- AGD-AC

- anogenital distance–anus to clitoral hood

- AGD-AF

- anogenital distance–anus to fourchette

- AGD-AP

- anogenital distance–anus to penis

- AGD-AS

- anogenital distance–anus to scrotum

- CDE

- controlled direct effect

- CI

- confidence interval

- DEHP

- di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- MBzP

- monobenzyl phthalate

- MCNP

- mono-carboxy-isononyl phthalate

- MCOP

- mono-carboxy-propyl phthalate

- MCPP

- mono-carboxy-propyl phthalate

- MEHP

- mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate

- MEP

- monoethyl phthalate

- MiBP

- mono-iso-butyl phthalate

- MnBP

- mono-n-butyl phthalate

- TIDES

- The Infant Development and the Environment Study

- UCSF

- University of California–San Francisco

- UMN

- University of Minnesota

- URMC

- University of Rochester Medical Center

- UW

- University of Washington

- VIF

- variance inflation factor.

References

- 1. Woodruff TJ, Zota AR, Schwartz JM. Environmental chemicals in pregnant women in the United States: NHANES 2003–2004. Environmental health perspectives. 2011;119:878–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zota AR, Calafat AM, Woodruff TJ. Temporal trends in phthalate exposures: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(3):235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gray LE, Ostby J, Furr J, Price M, Veeramachaneni DN, Parks L. Perinatal exposure to the phthalates DEHP, BBP, and DINP, but not DEP, DMP, or DOTP, alters sexual differentiation of the male rat. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58:350–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mylchreest E, Cattley RC, Foster PM. Male reproductive tract malformations in rats following gestational and lactational exposure to Di(n-butyl) phthalate: An antiandrogenic mechanism? Toxicol Sci. 1998;43:47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parks LG, Ostby JS, Lambright CR, et al. The plasticizer diethylhexyl phthalate induces malformations by decreasing fetal testosterone synthesis during sexual differentiation in the male rat. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58:339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burton GJ, Jauniaux E, Charnock-Jones DS. The influence of the intrauterine environment on human placental development. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hustin J, Schaaps JP. Echographic [corrected] and anatomic studies of the maternotrophoblastic border during the first trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jauniaux E, Gulbis B. Fluid compartments of the embryonic environment. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6:268–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nagy AM, Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D, Meuris S. Placental production of human chorionic gonadotrophin alpha and beta subunits in early pregnancy as evidenced in fluid from the exocoelomic cavity. J Endocrinol. 1994;142:511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huhtaniemi IT, Korenbrot CC, Jaffe RB. HCG binding and stimulation of testosterone biosynthesis in the human fetal testis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977;44:963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kremer H, Kraaij R, Toledo SP, et al. Male pseudohermaphroditism due to a homozygous missense mutation of the luteinizing hormone receptor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;9:160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chedane C, Puissant H, Weil D, Rouleau S, Coutant R. Association between altered placental human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) production and the occurrence of cryptorchidism: A retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buckberry S, Bianco-Miotto T, Bent SJ, Dekker GA, Roberts CT. Integrative transcriptome meta-analysis reveals widespread sex-biased gene expression at the human fetal-maternal interface. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20(8):810–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yaron Y, Lehavi O, Orr-Urtreger A, et al. Maternal serum HCG is higher in the presence of a female fetus as early as week 3 post-fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jukic AM, Weinberg CR, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ. The association of maternal factors with delayed implantation and the initial rise of urinary human chorionic gonadotrophin. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:920–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ridano ME, Racca AC, Flores-Martín J, et al. Chlorpyrifos modifies the expression of genes involved in human placental function. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33:331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Honkisz E, Zieba-Przybylska D, Wojtowicz AK. The effect of triclosan on hormone secretion and viability of human choriocarcinoma JEG-3 cells. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;34:385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fowler PA, Bhattacharya S, Gromoll J, Monteiro A, O'Shaughnessy PJ. Maternal smoking and developmental changes in luteinizing hormone (LH) and the LH receptor in the fetal testis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4688–4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swan SH, Sathyanarayana S, Barrett ES, et al. First trimester phthalate exposure and anogenital distance in newborns. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:963–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dean A, Sharpe RM. Clinical review: Anogenital distance or digit length ratio as measures of fetal androgen exposure: relationship to male reproductive development and its disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2230–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hallmark N, Walker M, McKinnell C, et al. Effects of monobutyl and di(n-butyl) phthalate in vitro on steroidogenesis and Leydig cell aggregation in fetal testis explants from the rat: Comparison with effects in vivo in the fetal rat and neonatal marmoset and in vitro in the human. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heger NE, Hall SJ, Sandrof MA, et al. Human fetal testis xenografts are resistant to phthalate-induced endocrine disruption. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1137–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lambrot R, Muczynski V, Lécureuil C, et al. Phthalates impair germ cell development in the human fetal testis in vitro without change in testosterone production. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silva MJ, Samandar E, Preaujr JL, Jr, Reidy JA, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Quantification of 22 phthalate metabolites in human urine. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;860:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hornung R, Reed L. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of nondetectable values. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 1990;5:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frederiksen H, Skakkebaek NE, Andersson AM. Metabolism of phthalates in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sathyanarayana S, Grady R, Redmon JB, et al. Anogenital distance and penile width measurements in The Infant Development and the Environment Study (TIDES): Methods and predictors. J Pediatr Urol. 2015;11:76.e1–e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lentini E, Kasahara M, Arver S, Savic I. Sex differences in the human brain and the impact of sex chromosomes and sex hormones. In: Cerebral Cortex. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013;2322–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15:615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goetgeluk S, Vansteelandt S, Goetghebeur E. Estimation of controlled direct effects. J Roy Stat Soc B. 2008;70:1049–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vansteelandt S. Estimating direct effects in cohort and case-control studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20(6):851–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman Hall, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barrett ES, Parlett LE, Sathyanarayana S, et al. Prenatal exposure to stressful life events is associated with masculinized anogenital distance (AGD) in female infants. Physiol Behav. 2013;114–115:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Filicori M, Fazleabas AT, Huhtaniemi I, et al. Novel concepts of human chorionic gonadotropin: Reproductive system interactions and potential in the management of infertility. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Welsh M, Saunders PT, Fisken M, et al. Identification in rats of a programming window for reproductive tract masculinization, disruption of which leads to hypospadias and cryptorchidism. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1479–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mitchell RT, Mungall W, McKinnell C, et al. Anogenital distance plasticity in adulthood: Implications for its use as a biomarker of fetal androgen action. Endocrinology. 2015;156:24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scott HM, Mason JI, Sharpe RM. Steroidogenesis in the fetal testis and its susceptibility to disruption by exogenous compounds. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:883–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eisenberg ML, Lipshultz LI. Anogenital distance as a measure of human male fertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:479–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mendiola J, Roca M, Mínguez-Alarcón L, et al. Anogenital distance is related to ovarian follicular number in young Spanish women: A cross-sectional study. Environmental Health. 2012;11:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Adibi JJ, Whyatt RM, Williams PL, et al. Characterization of phthalate exposure among pregnant women assessed by repeat air and urine samples. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:467–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]