Abstract

A 24 factorial design was used to optimize the activators regenerated by electron transfer-atom transfer radical polymerization (ARGET-ATRP) grafting of sodium styrene sulfonate (NaSS) films from trichlorosilane/10-undecen-1-yl 2-bromo-2-methylpropionate (ester ClSi) functionalized titanium substrates. The process variables explored were: (1) ATRP initiator surface functionalization reaction time; (2) grafting reaction time; (3) CuBr2 concentration; and (4) reducing agent (vitamin C) concentration. All samples were characterized using x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Two statistical methods were used to analyze the results: (1) analysis of variance with , using average XPS atomic percent as the response; and (2) principal component analysis using a peak list compiled from all the XPS composition results. Through this analysis combined with follow-up studies, the following conclusions are reached: (1) ATRP-initiator surface functionalization reaction times have no discernable effect on NaSS film quality; (2) minimum (≤24 h for this system) grafting reaction times should be used on titanium substrates since NaSS film quality decreased and variability increased with increasing reaction times; (3) minimum (≤0.5 mg cm−2 for this system) CuBr2 concentrations should be used to graft thicker NaSS films; and (4) no deleterious effects were detected with increasing vitamin C concentration.

I. INTRODUCTION

Controlling surface properties is important in a number of fields.1–4 One strategy to do so is polymer grafting. Activators regenerated by electron transfer-atom transfer radical polymerization (ARGET-ATRP) is a versatile and scalable method for polymer synthesis. When combined with a material-specific strategy for immobilizing an ATRP initiator, ARGET-ATRP can be used to modify most metal, oxide, and ceramic surfaces,1,3,5 as well as polymer surfaces.6–9 However, much of the fundamental understanding of ARGET-ATRP, or more generally ATRP, is based on studies focusing on solution-phase polymerizations.10–17 While publications describing ATRP and ARGET-ATRP grafting of different polymers from a variety of surfaces are plentiful in the literature, the authors are aware of few studies that explore in detail the relationship between process variables and film quality. (We define high quality films to be thick and laterally homogeneous—i.e., hole and defect free.) Therefore, in this study, we use surface analysis techniques to characterize and optimize the grafting of sodium styrene sulfonate (NaSS) from trichlorosilane/10-undecen-1-yl 2-bromo-2-methylpropionate-functionalized titanium surfaces (Fig. 1). Interest in NaSS extends to a number of applications, such as an antiflocculating agent, emulsifier, catalyst, and for use in ion-exchange resins and membranes.18–21 It has also shown promise as a strategy to increase the osseointegration of titanium22–25 and poly(ethylene terephthalate)26–28 biomedical implants. To investigate possible reasons for the increased osseointegration of these materials, in future studies, the authors intend to test the hypothesis that the NaSS-grafted surfaces preferentially adsorb certain plasma proteins in an orientation and conformation that modulates the foreign body response and promotes formation of new bone. A necessary prerequisite for doing so is the ability to reliably produce sufficient quantities of high quality NaSS-grafted substrates. Therefore, the goals of this work are twofold: (1) examine the influence of experimental conditions on NaSS grafting; and (2) by doing so, further our general understanding of ARGET-ATRP grafting from surfaces. To this end, a 24 factorial design was performed to study the following variables: (1) ATRP initiator surface functionalization reaction time; (2) grafting reaction time; (3) CuBr2 concentration; and (4) reducing agent (vitamin C) concentration.

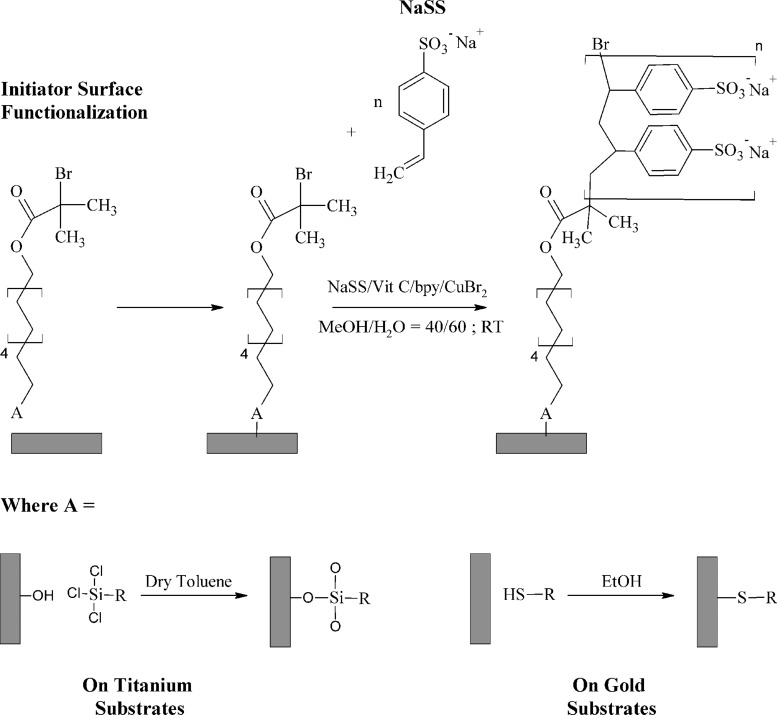

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the two-step NaSS grafting procedure. Step 1: surface immobilization of the ATRP initiator using a material-specific functionalization strategy to form either thiol (on Au) or silane (on titanium) self-assembled monolayers. Step 2: ARGET-ATRP grafting of NaSS from the surface-bound initiator.

Even though statistical experimental design methods are extremely useful in efficiently optimizing process conditions, they rarely go as planned. Under “real world” conditions, undesired and uncontrolled changes in process conditions are routinely encountered. These can obscure trends and further complicate analysis of the experimental design results. The current work is no exception, where an analyzer upgrade for the x-ray photoelectron spectrometer occurred during data collection. Therefore, in addition to the traditional analysis of variance (ANOVA), we employed principal component analysis (PCA) to evaluate the factorial design results. Through this combination of statistical analyses, we were able to account for the effect of the analyzer upgrade on the data and draw meaningful conclusions regarding optimal NaSS grafting conditions, which is the main focus of this paper.

II. EXPERIMENT

A. Materials

Silicon wafers (Silicon Valley Microelectronics, Inc., San Jose, CA) were diced into 1 × 1 cm2 substrates using a diamond saw. Titanium substrates were fabricated by evaporation of 100 nm of titanium from an electron-beam heated titanium target onto diced silicon substrates at room temperature and vacuum pressures <3 × 10−6 Torr. Gold substrates, also 100 nm thick, were fabricated in the same way, first depositing a 5 nm titanium adhesion layer. Methanol, acetone, dichloromethane, toluene, phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 0.010 M phosphate, 0.138 M sodium chloride, 0.0027 M potassium chloride, pH 7.4), Cu(II) bromide (>99.0%), 2,2′-bipyridine (bpy) (≥99%), vitamin C (≥98%), and NaSS (≥90%) were all purchased from Sigma. Ethanol (200 proof) was purchased from Decon Laboratories. The toluene was dried by storing over 4A molecular sieves; the rest of the chemicals were used as received. The synthesis of the ATRP initiator, trichlorosilane/10-undecen-1-yl 2-bromo-2-methylpropionate (henceforth referred to as ester ClSi), has been described previously.7 An amide (referred to as amide ClSi) version of the same molecule was graciously provided by the Jiang group at the University of Washington. Bromoisobutyrate undecyl disulfide (99%) (henceforth referred to simply as thiol, since it forms a gold–thiolate bond on the surface) was purchased from Assemblon.

B. Substrate cleaning and ATRP-initiator functionalization

Prior to the e-beam deposition, substrates were cleaned by sonicating twice for 5 min each sequentially in dichloromethane, acetone, and methanol. The e-beam deposited titanium substrates were functionalized in a 0.2 vol. % solution of ester ClSi in dry toluene for the length of time specified by the factorial design. Functionalized substrates were rinsed in dry toluene followed by methanol, and then briefly dipped in 1 mM NaOH to cross-link the surface silanes and neutralize HCl byproducts.

E-beam deposited gold substrates were rinsed with ethanol and immersed in a 1 mM solution of thiol in ethanol for 18–24 h. The substrates were then rinsed with ethanol, sonicated for 1–3 min to remove any unbound thiol, and rinsed once more with ethanol. Both the titanium and gold functionalization reactions were performed at room temperature in N2-backfilled glass test tubes stoppered with rubber septa.

C. ARGET-ATRP

The ARGET-ATRP reaction solids were weighed into three 20 ml glass scintillation vials. The first contained 203 mg (98.6 mmol) of NaSS monomer dissolved in 1.2 ml 18 Ω de-ionized (DI) H2O. The second contained CuBr2 and bpy (1:2 ratio) dissolved in 2.4 ml methanol and 1.2 ml 18 Ω DI H2O. The third vial contained vitamin C dissolved in 1.2 ml 18 Ω DI H2O. The total solvent volume was 6 ml (60/40 H2O/methanol). The amount of CuBr2/bpy and vitamin C varied depending on the treatment combination as dictated by the experimental design. The catalyst solution, along with two initiator-functionalized substrates, was added to the NaSS vial, making sure that the substrates stayed face up and did not overlap each other. NaSS grafting was initiated upon addition of the vitamin C solution to the reaction vial, which was then capped and sealed with parafilm. Since excess vitamin C is present during the reaction, it is not necessary to degas the reaction solvent. After the allotted time specified by the factorial design the substrates were rinsed with 18 Ω DI H2O, soaked in PBS for several hours, and then soaked overnight in 18 Ω DI H2O to remove any residual catalyst, excess sodium/buffer salts, and monomer. Finally, the grafted substrates were rinsed again with 18 Ω DI H2O, gently dried with a stream of N2, and stored under N2 until analyzed.

D. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) data were acquired on an SSI S-probe instrument (Surface Science Instruments, Mountain View, CA). Half way through the first replicate of the factorial design, the analyzer was upgraded and the photoelectron takeoff angle (TOA) changed from 55° to 0°. Here, the photoelectron TOA is defined as the angle between the surface normal and the axis of the analyzer lens. All spectra were acquired using a monochromatic Al Kα1,2 x-ray source (hν = 1486.6 eV). Atomic compositions were calculated from peak areas obtained from survey scans (0–1100 eV) with analyzer pass energy of 150 eV, a 1 eV step size, and a 100 ms dwell time. Carbon chemical shifts were determined from high-resolution C1s spectra obtained with analyzer pass energy of 50 eV, a 0.065 eV step size, and 100 ms dwell time. All samples were grounded to the spectrometer and run as conductors. Binding energy scales were calibrated by setting the CHx peak in the C1s region to 284.6 eV, and a linear background was subtracted for all peak area quantifications. The peak areas were normalized by the manufacturer supplied sensitivity factors, and surface concentrations were calculated using Hawk Data Analysis 7 (Service Physics, Inc., Bend, OR).

E. Atomic force microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images were acquired on a Dimension Icon (Bruker, Santa Barbara, CA) in TappingMode™ using OTESPA rectangular cantilevers (k = 40 N/m; Bruker, Santa Barbara, CA). Images were line and plane flattened as necessary the using the NanoScope Analysis software package. Scratch-test measurements were also performed to determine NaSS film thicknesses. These consisted of using a high deflection set point in contact mode to scratch a 5 × 5 μm2 hole in the NaSS film, reducing the deflection set point, and increasing the scan size to 20 × 20 μm2 to determine the depth of the scratched hole. This procedure was iterated, each time scratching with a higher deflection set point until the thickness remained constant between iterations.

F. Vibrational sum frequency generation spectroscopy

Sum frequency generation (SFG) spectra were measured with a ps-pulsed laser system (EKSPLA, Nd:YAG and OPA/OPG/DFG). Spectra were collected for ester ClSi films on Ti surfaces, functionalized for either 1 day or 7 days, to determine the effect of reaction time on the ester ClSi film quality. The incident angles relative the surface normal were 60° and 62° for the infrared (IR) and visible beams, respectively. The ppp (p-polarized SFG, p-polarized visible, and p-polarized IR) polarization combination was used for all spectra. Average data acquired from three replicates of each sample (1 day and 7 days) were analyzed for the ester and C-H spectral regions (ester: 1700–1800 cm−1 and C-H: 2800–3000 cm−1), with one exception (7 days, ester region: 1700–1800 cm−1) where average data acquired from four replicates were analyzed. For the ester region, a step size of 1 cm−1 was used with 600 acquisitions per step, while a step size of 2 cm−1 and 400 acquisitions per step were used for the C-H region. To account for any variations in IR and visible intensities that occurred during spectra acquisition, all data points were normalized against a signal produced in parallel from an SFG-active crystal (ZnS).

G. Factorial design

A 24 factorial design was performed varying (A) ester ClSi reaction time, (B) grafting reaction time, (C) CuBr2 concentration, and (D) vitamin C concentration (Table I). Two duplicate samples were prepared and analyzed at each treatment combination. The entire design was replicated twice totaling four samples per treatment combination. The run order was randomized but within replicates only. The design matrix and response are listed in Table II.

Table I.

Factors and treatment levels.

| Factor | Symbol | Low (−1) | High (1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ester ClSi reaction time | A | 24 h | 72 h |

| Grafting reaction time | B | 2 4 h | 7 2 h |

| CuBr2 | C | 1 mg cm−2 | 2 mg cm−2 |

| Vitamin C | D | 39.5 mg cm−2 | 79 mg cm−2 |

| Covariate | — | Preupgrade | Postupgrade |

Table II.

Experimental conditions and results.

| Treatment combination | Ester ClSi reaction time (h) | Grafting reaction time (h) | CuBr2 (mg cm−2) | Vitamin C (mg cm−2) | Covariatea | Replicate 1 | Replicate 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||||||||

| (1)b | −1 | (24) | −1 | (24) | −1 | (1) | −1 | (79) | 1 | 1.11 | 0.17 |

| A | 1 | (72) | −1 | (24) | −1 | (1) | −1 | (79) | −1 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| B | −1 | (24) | 1 | (72) | −1 | (1) | −1 | (79) | −1 | 2.29 | 3.55 |

| AB | 1 | (72) | 1 | (72) | −1 | (1) | −1 | (79) | 1 | 1.21 | 0.18 |

| C | −1 | (24) | −1 | (24) | 1 | (2) | −1 | (79) | −1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AC | 1 | (72) | −1 | (24) | 1 | (2) | −1 | (79) | 1 | 1.15 | 0.12 |

| BC | −1 | (24) | 1 | (72) | 1 | (2) | −1 | (79) | 1 | 0.64 | 2.34 |

| ABC | 1 | (72) | 1 | (72) | 1 | (2) | −1 | (79) | −1 | 0.22 | 1.87 |

| D | −1 | (24) | −1 | (24) | −1 | (1) | 1 | (158) | −1 | 0.48 | 0.43 |

| AD | 1 | (72) | −1 | (24) | −1 | (1) | 1 | (158) | 1 | 1.16 | 0.18 |

| BD | −1 | (24) | 1 | (72) | −1 | (1) | 1 | (158) | 1 | 0.62 | 2.46 |

| ABD | 1 | (72) | 1 | (72) | −1 | (1) | 1 | (158) | −1 | 0.00 | 1.15 |

| CD | −1 | (24) | −1 | (24) | 1 | (2) | 1 | (158) | 1 | 0.76 | 1.44 |

| ACD | 1 | (72) | −1 | (24) | 1 | (2) | 1 | (158) | −1 | 0.00 | 1.09 |

| BCD | −1 | (24) | 1 | (72) | 1 | (2) | 1 | (158) | −1 | 0.00 | 0.36 |

| ABCD | 1 | (72) | 1 | (72) | 1 | (2) | 1 | (158) | 1 | 1.22 | 1.71 |

The covariate levels apply to replicate 1 only. The covariate level was 1 (analyzer angle of 0°) throughout replicate 2.

The treatment combination “(1)” is where low (−1) levels are used for all factors. See Table I for these experimental conditions.

H. Data analysis

The factorial design was analyzed using both ANOVA with and PCA. For the ANOVA, average XPS atomic percent was chosen as the response. XPS data are technically “count-based,” thus the decision to use square-root transformed titanium compositions.29 Since the experimental order was randomized within replicates only, blocking was performed on replicates. The additional variance added to the system by the analyzer upgrade was accounted for by including a covariate in the ANOVA. Also, some spectra were discarded due to sample charging. Even with the discarded data at least seven spectra were collected for each treatment combination, whereas the remaining responses represent a total of twelve measurements. All ANOVA were done “by hand” in MS Excel. Chapters 3, 5, and 6 from Ref. 29 are recommended as a resource for more information about factorial designs.

PCA, previously described in detail,30–32 is a multivariate analysis technique used to identify principal sources of variation between sample spectra. Briefly, PCA can be described as a clustering algorithm with two outputs: a scores plot and a loadings plot. Samples that cluster closely together in the scores plot are considered more similar to each other than those that do not. The loadings plot explains the differences between the samples. Samples with negative scores are associated with variables with negative loadings, and vice versa. Peak lists for all 173 XPS spectra—composed of S, C, Ti, O, and Na—were imported into a series of scripts written by NESAC/BIO for MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA).33,34 Although data normalization is often performed prior to PCA, XPS compositions are in the form of atomic percentages and therefore already normalized. The data were, however, square-root transformed and mean centered to be consistent with the ANOVA procedure and to ensure that variance within the data set was due to differences in sample variances rather than in sample means.

III. RESULTS/DISCUSSION

Since the focus of this work is optimizing ARGET-ATRP grafting conditions, the extensive set of spectral data from the NaSS-grafted substrates used in this study is not provided here. However, readers desiring further details regarding characterization of NaSS-grafted substrates are directed to reference,35 which describes characterization of NaSS-grafted titanium and silicon substrates using XPS, AFM, time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS), and spectral ellipsometry.

A. Factorial design analysis/results

The factorial design was analyzed using both ANOVA and PCA. Three main advantages of ANOVA are: (1) causal relationships can be established between the effects and the response; (2) higher-level (two-way, three-way, etc.) interaction effects can be investigated; and (3) the analysis typically yields a physically meaningful regression model that can be used to optimize process conditions within the investigated experimental space.29 However, only one response can be considered at a time and any remaining information is discarded. This is illustrated by the system at hand. Average XPS atomic percent is a logical choice of response since increasing substrate signal is indicative of either patchy or thin grafted NaSS films and therefore inversely proportional to film quality. However, this approach neglects the remaining elements (C, S, Na, etc.) found in the XPS composition results. PCA, on the other hand, is able to handle complex data sets, meaning that all of the XPS composition results can be simultaneously analyzed.

The ANOVA results and regression model can be found in Table III and Eq. (1). Plots of the residuals are found in Figure S1 of the supplementary material.36 The significant factors are B (grafting reaction time; P = 4.5 × 10−3), AC (the two-way interaction between ester ClSi reaction time and CuBr2 amount; P = 0.02), and BD (the two-way interaction between grafting reaction time and vitamin C amount; P = 0.04).

| (1) |

The covariate was also significant, indicating that the analyzer upgrade had an impact on the response. This is expected since the sampling depth—defined as three times the inelastic mean free path (λ) times the cosine of the TOA [Eq. (2)]—nearly doubled with the analyzer upgrade. The relative concentrations of overlayer (NaSS) to substrate (TiO2) signals will change with increasing sampling depth

| (2) |

Table III.

ANOVA results.

| Source | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | Foa | Fcrita | P-value | Significant? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.87 | 1 | 0.87 | 2.35 | 4.60 | 0.15 | |

| B | 4.26 | 1 | 4.26 | 11.45 | 4.60 | 4.5 × 10−3 | Yes |

| C | 0.14 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 4.60 | 0.54 | |

| D | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 4.60 | 0.59 | |

| AB | 0.53 | 1 | 0.53 | 1.41 | 4.60 | 0.25 | |

| AC | 2.51 | 1 | 2.51 | 6.76 | 4.60 | 0.02 | Yes |

| AD | 0.85 | 1 | 0.85 | 2.30 | 4.60 | 0.15 | |

| BC | 0.52 | 1 | 0.52 | 1.40 | 4.60 | 0.26 | |

| BD | 1.84 | 1 | 1.84 | 4.96 | 4.60 | 0.04 | Yes |

| CD | 0.18 | 1 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 4.60 | 0.50 | |

| ABC | 1.58 | 1 | 1.58 | 4.26 | 4.60 | 0.06 | |

| ABD | 1.43 | 1 | 1.43 | 3.84 | 4.60 | 0.07 | |

| ACD | 0.29 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.79 | 4.60 | 0.39 | |

| BCD | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.60 | 0.97 | |

| ABCD | 0.76 | 1 | 0.76 | 2.04 | 4.60 | 0.18 | |

| Covariate | 2.52 | 1 | 2.52 | 6.77 | 4.60 | 0.02 | Yes |

| Blocks | 1.23 | 1 | 1.23 | 3.32 | 4.60 | 0.09 | |

| Error | 5.20 | 14 | 0.37 | ||||

| Total | 24.84 | 31 |

Fo is referred to as the test statistic and is calculated by dividing the mean square for each effect by the mean square error. Fcrit is the critical value, based on the F-distribution, which the test statistic must be greater than for an effect to be considered significant.

Interpretation of the ANOVA results and regression model is somewhat challenging for multiple reasons. First, from the goodness-of-fit statistics (Table IV), Eq. (1) does not account for much of the variance in this system (R2 values significantly less than 1) despite the negative value, which suggests that the data are overfit. Next, interaction terms are significant ( and ), when their constituent main effects are not (, , and ). This is could be a residual artifact of the analyzer upgrade and the discarded spectra, for which the covariate could not adequately compensate. However, further complicating matters is the fact that grafting reaction time is involved in two terms—as a main effect () and also as a two-way () interaction—with opposite signs. The main effect is the most significant term in the regression model and the positive coefficient suggests that titanium signal increases with increasing reaction time. Or, stated another way, film quality decreases with increasing reaction time. However, the two-way interaction () coefficient is negative suggesting that the combination of long reaction times and high concentrations of vitamin C lead to increased NaSS film quality. This is more likely a false positive than a physically meaningful result since the vitamin C concentration term () was not significant (P = 0.59).

Table IV.

Goodness-of-fit statistics for the regression model [Eq. (1)].

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| 0.35 | |

| 0.30 | |

| −0.23 |

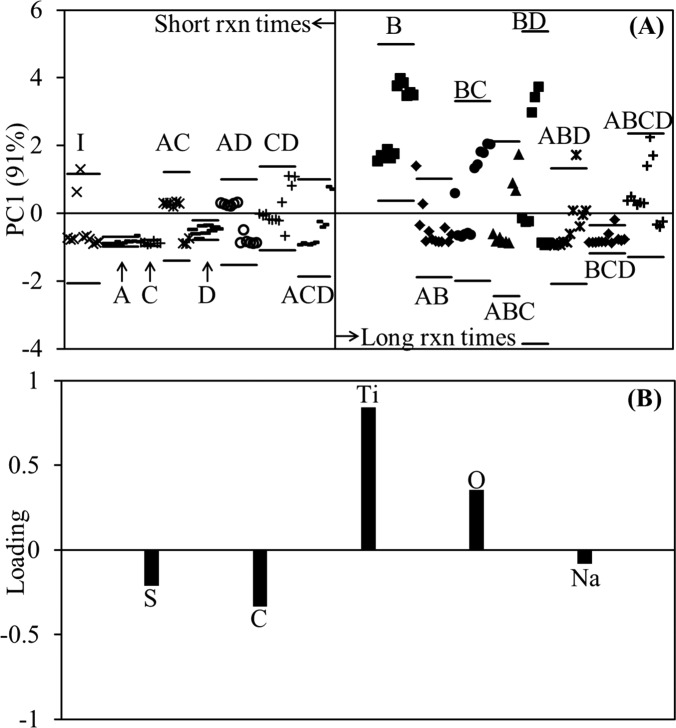

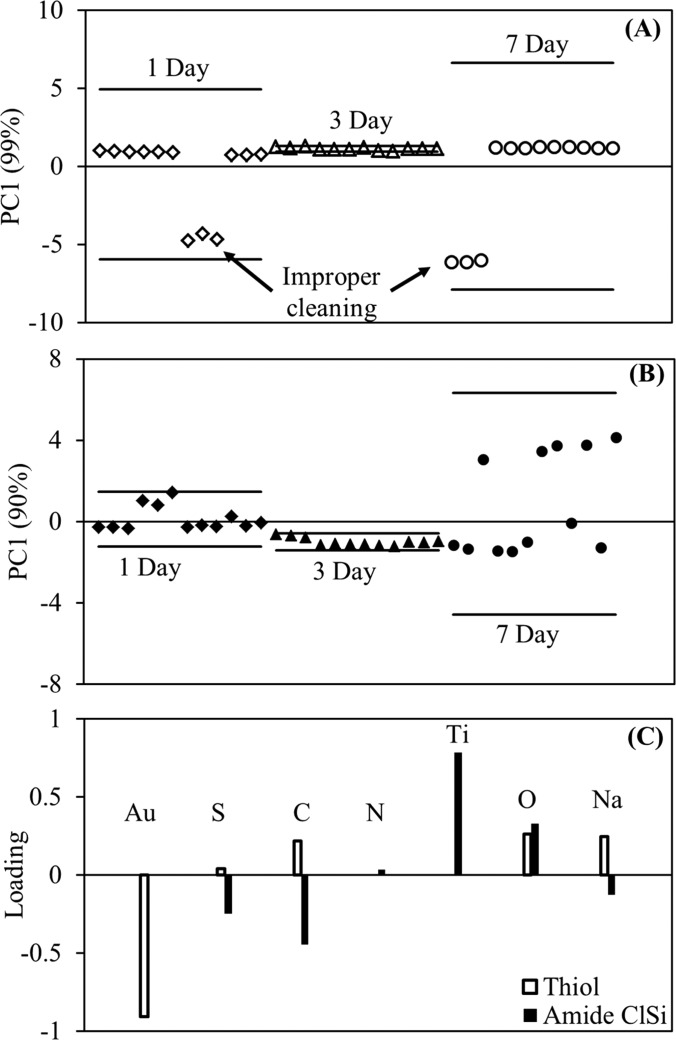

We next turned to PCA to clarify the conflicting ANOVA results. The first thing to notice is that the first principal component (PC1) shown in Fig. 2 accounts for 91% of the variance in the data compared to only 30%–35% for the ANOVA. Next, the treatment levels corresponding to short reaction times (B = −1) are relatively tightly clustered and the majority of the data fall below zero on the PC1 scores plot [Fig. 2(a)]. According to the loadings plot [Fig. 2(b)], negative scores are associated with C, S, and Na from the NaSS layer and positive scores with Ti and O from the substrate.

Fig. 2.

PC1 vs sample type (A) and the corresponding loadings plot (B) for PCA of the factorial design results. The labels in (A) correspond to the factorial design treatment combinations listed in Table II. These results suggest NaSS film quality and reproducibility decreases with increasing ARGET-ATRP grafting reaction time.

Conversely, the scores for the treatment levels corresponding to long reaction times (B = 1) vary widely and much of the data falls above the x-axis. This indicates that with increasing reaction time the samples move from being more NaSS-like to having more contributions from the substrate, corroborating the ANOVA findings. The position and scatter of the scores for treatment combinations involving long reaction times did not appear to improve with high vitamin C content [BD, ABD, BCD, and ABCD in Fig. 2(a)], lending credence to the assertion that the two-way interaction term is a false positive. To further support this claim, another ANOVA was performed using the PC1 scores as the response (Tables S1 and S2 of the supplementary material). In these results, the (P = 0.01) and (P = 0.02) terms are retained, while is no longer significant (P = 0.07). Also interesting is that the covariate is no longer significant (P = 0.07), meaning that PCA was able to diminish the effect of the analyzer upgrade. However, PCA was unable to resolve the term and neither statistical analysis method is able to supply mechanistic explanations for the observed results. Therefore, studies were launched to investigate the effect ClSi reaction time (1), ARGET-ATRP reaction time (2), and CuBr2 amount (3) in isolation, and also the AC and BD interactions.

B. ClSi reaction time (A)

While the (ClSi reaction time) term was not found to be significant by either ANOVA or PCA, the (two-way interaction between ClSi reaction time and catalyst amount) was retained by both methods. However, it is unlikely that this result is physically meaningful since these two factors are physically decoupled: i.e., there is no catalyst present during the ClSi functionalization, and the grafting and functionalization steps are prepared in different vials. More likely is that the two-way interaction term is registering the significance of one or both of the main effects, which was obscured by the analyzer upgrade and/or discarded data. In fact, catalyst amount (C) had the most (5) discarded spectra of any treatment combination. It is not surprising that this reduction in the number of data points complicates analysis and interpretation of the factorial design results. Therefore, ClSi reaction time and catalyst amount were studied to determine which of these main effects is significant. The results of the ClSi reaction time study are discussed in this section. Results of the catalyst study are discussed later.

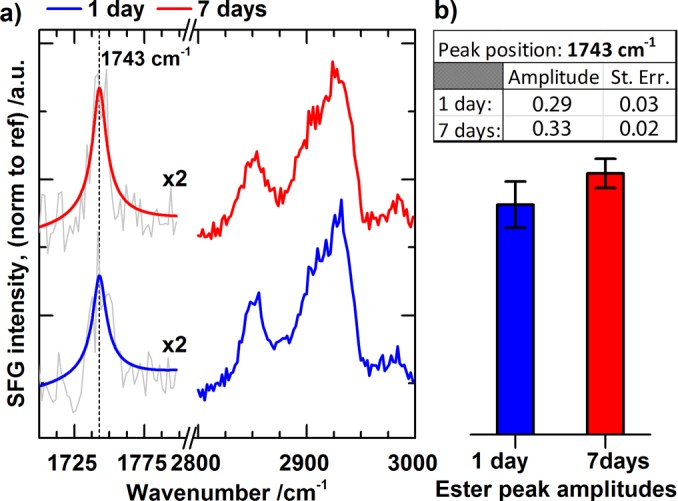

Our hypothesis was that the ClSi film quality—ordering and/or uniformity—increases with increasing reaction time. Corresponding increases in NaSS film quality might be due to a greater availability or access to the surface-bound halide from which the grafting reaction is initiated. While near-monolayer film coverages are likely achieved in a matter of hours, full monolayer formation and ordering might take a few, or even several days.37,38 Therefore, to test this hypothesis ClSi films were synthesized using 1, 3, and 7 day reaction times. Film chemical uniformity, morphology, and ordering were investigated using XPS, AFM, and SFG, respectively. None of these techniques revealed any significant differences between ClSi films synthesized for different lengths of time. However, interesting SFG results were obtained regarding ester ClSi film structure.

SFG spectra in the C-H and ester regions were recorded to compare ester ClSi films prepared on titanium during 1 and 7 days reaction times (Fig. 3). For films such as the ester ClSi, the relative spectral contributions of methyl and methylene vibrations in the C-H region (2800–3000 cm−1) are related to alkane chain conformation.9,39 SFG probes IR and Raman active vibrational modes of molecules, which are neither isotropic in arrangement nor have a center of inversion.40 A perfectly ordered alkane chain with the methylene groups in an all-trans conformation does have a center of inversion in between the methylene groups.9,41,42 In such a scenario, the C-H spectral region would be dominated by SFG signals from the terminal methyl vibrations. However, our results show that peaks from methylene vibrations (around 2855 cm−1 for symmetric and around 2920 cm−1 for asymmetric vibrations) dominate the C-H region, indicating that the alkane chains contain gauche defects. Most importantly, the spectra for 1 day and 7 days reaction times overlap almost perfectly showing that no significant change in molecular conformation of the alkane chain is observable by SFG. We also measured the SFG spectra for the ester region (1700–1800 cm−1) and detected the carbonyl stretching peak of the ester group at 1743 cm−1.43,44 Since a species must be at least partially ordered to be SFG active, the presence of an SFG signal confirms partial ordering of the ester group.

Fig. 3.

(Color online) SFG spectra of the C-H region (2800–2900 cm−1) for ClSi films functionalized for 1 day (blue) and 7 days (red), respectively. For the ester region at 1743 cm−1, the gray traces are averaged data, while the blue and red traces are fits made with Eq. (3). The vertical line at 1743 cm−1 denotes the peak position for the fits. For the C-H region, only the averaged data are presented. The amplitudes of the fits in the ester region, with error bars showing standard errors of the fits, are included in the table and bar-plot. The data indicate that the films prepared for 1 day and 7 days reaction times are of similar quality.

To quantitatively compare the spectral intensities in the ester region for the 1 and 7 days reaction times, the spectra were fitted with

| (3) |

where is the second order susceptibility; is the nonresonant part; , , are the peak amplitude, peak wavenumber, and damping factor (peak width) for the kth IR and Raman active vibration; and is the IR wavenumber. The ester peak fits for 1 (blue) and 7 (red) days reaction times are presented in Fig. 3, in which the bar plot displays the value of the peak amplitudes from the two fits. Although the mean values are slightly different, they are within experimental error. This, in conjunction with the striking similarity of the spectra in the C-H region, provides further evidence that the ClSi films prepared during 1 and 7 days reaction times are similar. As mentioned above, this conclusion is consistent with the results from the XPS and AFM experiments (Figs. S3 and S4 of the supplementary material). It is therefore unlikely that an increased ClSi reaction time leads to an improved NaSS film quality.

C. Grafting reaction time (B)

Grafting reaction time was involved in the ANOVA regression model [Eq. (1)] as both a main effect () and interaction term (). Both ANOVA and PCA confirmed the significance of the main effect, which was strongly correlated with decreased NaSS film quality leading to increased titanium signal. For reasons discussed above the significance of the interaction term is thought to be a false positive.

It is surprising that film quality should decrease with increasing grafting reaction time. Assuming the stability of the grafted film under reaction conditions, film properties should remain constant once the reaction reaches completion. NaSS film stability under the reaction (i.e., aqueous) conditions is seemingly a safe assumption since no degradation has been observed in the final step of the grafting procedure, which is to leach any residual catalyst from the films by soaking them in PBS and then water over night. Therefore, we hypothesized that the mechanism for decreased NaSS film quality is hydrolysis of the ester ClSi head group, which may be somehow affected by vitamin C. To test this hypothesis a 22 factorial design was performed: functionalized titanium substrates were soaked for 24 or 72 h in 60/40 H2O/methanol (the reaction solvent) with or without vitamin C (Table V). Samples were analyzed with XPS before and after soaking, collecting three composition and one high-resolution C1s spectra per sample. The design was replicated twice yielding a total of six composition and two high-resolution C1s measurements per treatment. The compositions and high-resolution C1s results are found in Table S3 of the supplementary material.

Table V.

ClSi hydrolysis 22 factorial design: factors and treatment levels.

| Factor | Symbol | Low (−1) | High (1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | A | 0 mg | 39.5 mg |

| Soak time | B | 24 h | 7 2 h |

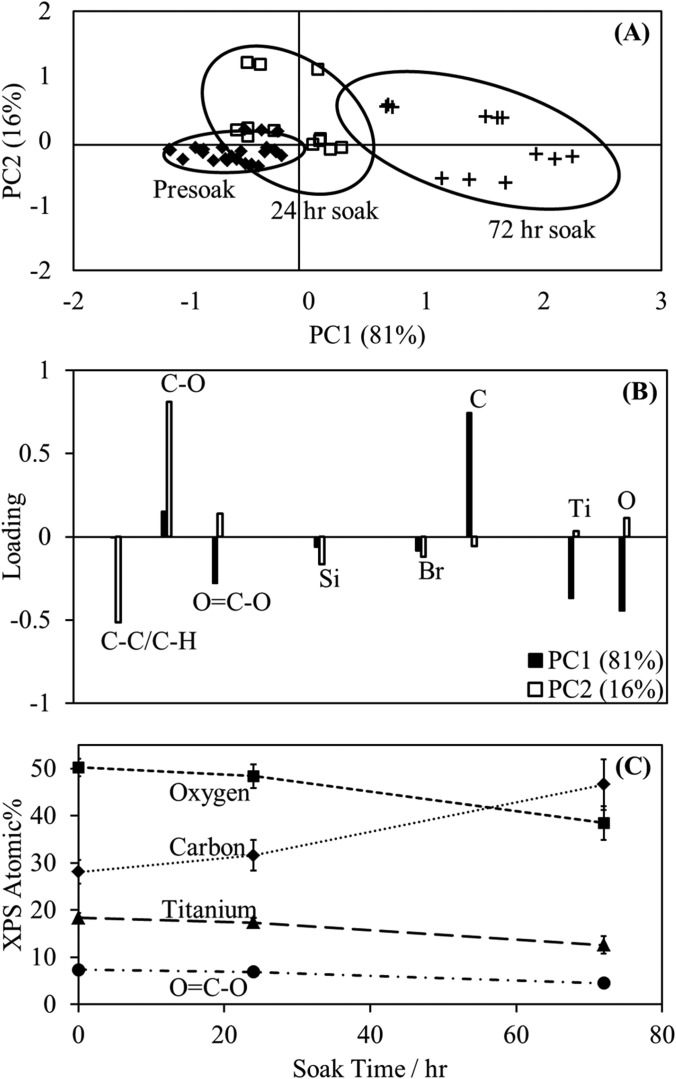

The data were again analyzed using PCA. Two PCs were retained that captured 97% of the variance in the data. The PC1 scores increase with soak time corresponding to an increase in C and a decrease in O, Ti, and the O=C-O high resolution C1s peak (Fig. 4). There is no obvious separation along PC2. The observed decrease in O=C-O signal with reaction time could be a sign of degradation of the ester head group. Loss of the head group would also explain the decrease in oxygen signal. However, a lack of decrease in the Br signal, which would also be expected, combined with the increase in C suggests these trends could be due to attenuation by a contamination layer rather than degradation.

Fig. 4.

Results of a study testing the stability of the ether ClSi ATRP initiator in the reaction solvent. PC1 vs PC2 scores plot (A) with corresponding loadings (B) and XPS compositions (C) for ester ClSi films soaked in 60/40 H2O/MeOH for up to 72 h. Variability of the ClSi film chemical composition increases with soak time, though it was determined that this was due to adsorption of an adventitious carbon contamination layer.

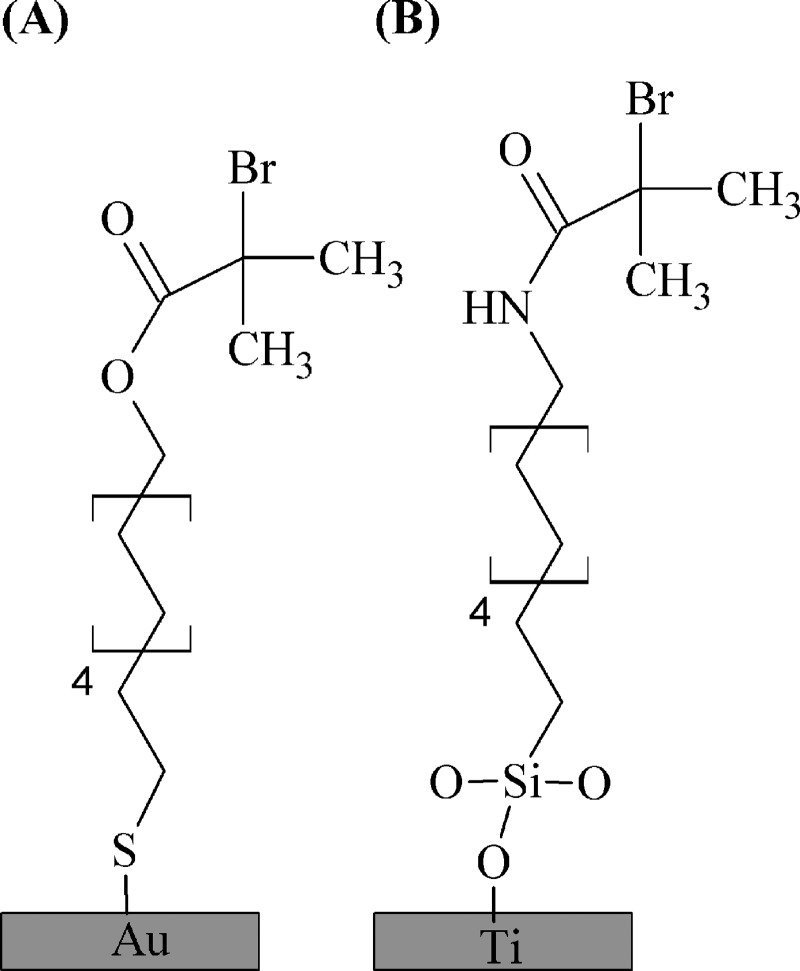

To confirm this conclusion, and to test for hydrolysis of the siloxane bonds tethering the ClSi initiators to the titanium, the hydrolysis study was expanded to include a thiol and amide version of the same initiator (Fig. 5). Should the siloxane bonds hydrolyze, the amide ClSi films will show signs of degradation while the thiol films will remain unchanged. If the ester group is in fact hydrolyzing, then the thiol films will degrade and the amide ClSi films will remain intact. The XPS composition and high resolution C1s spectra were analyzed using PCA, which found differences with soak time neither for the thiol nor the amide ClSi (Figs. S5 and S6 of the supplementary material). This apparently confirms that the decrease in the O=C-O signal observed for the ester ClSi was due to attenuation by a carbonaceous overlayer—i.e., the XPS ester carbon signal reduction was due to a layer of carbon contamination adsorbed from the ambient—rather than degradation of the ester head group. However, still unexplained is the cause of the NaSS film degradation with increasing grafting reaction time.

Fig. 5.

Schematic showing the thiol on gold (A) and amide ClSi on titanium (B) ATRP initiators.

The effect of grafting reaction time on NaSS film quality was also assessed for the amide ClSi-functionalized titanium and thiol-functionalized gold substrates. Low (−1) levels were used for all process variables except grafting reaction time, which varied between one day and seven days. Two duplicate samples were prepared at each time point and the entire experiment was replicated twice. Three XPS composition spectra were collected for each sample and compiled into a PCA peak list. PC1 scores for the films grafted from gold substrates [Fig. 6(a)] show very little scatter with grafting reaction time and are associated with S, C, O, and Na—all constituents of NaSS films. This is with the exception of two samples where the grafting reaction appears to have failed, most likely due to improper substrate cleaning leading to the failure of the thiol-functionalization step. No separation between the remaining samples was detected when these outliers were excluded from the PCA. From these results, film quality does not appear to be dependent on grafting reaction time for NaSS films grafted from thiol-functionalized gold surfaces. At short reaction times the amide ClSi PC1 scores [Fig. 6(b)] also show low scatter—minus one errant sample—and are associated with S, C, and Na from the NaSS film. However, a great deal of scatter is observed for the seven-day grafting reaction time point, with about half the data associated with Ti and O from the substrate. This is in agreement with the ester ClSi results [Fig. 2(a)], where at longer reaction times the scatter increased drastically and the samples became increasingly associated with the composition of the substrate rather than NaSS. That this was not observed in the hydrolysis study may be that the cause is somehow linked with the catalyst complex. The MSDS lists CuBr2 as corrosive and the authors also observed corrosion of metal utensils used to weigh out the CuBr2 powder. Thus, even though in low concentrations, it may be that the catalyst damages the titanium substrates over time. As a noble metal, gold would be resistant to such corrosive effects, explaining why no NaSS film degradation was observed on these substrates. Further study is needed to test this hypothesis.

Fig. 6.

Results of a study testing the effect of reaction time on NaSS film quality for films grafted from thiol (on gold) and amide ClSi (on titanium) ATRP initiators (Fig. 5). PC1 vs sample scores plots for NaSS films on gold using the thiol ATRP initiator (A), and on titanium using the amide ClSi ATRP initiator (B) for grafting reaction times up to 7 days. The corresponding loadings are in (C). Except for two improperly cleaned substrates, NaSS film quality appears constant with reaction time on gold, while quality and reproducibility decreases with increasing reaction time when grafted from the amide ClSi initiator on titanium.

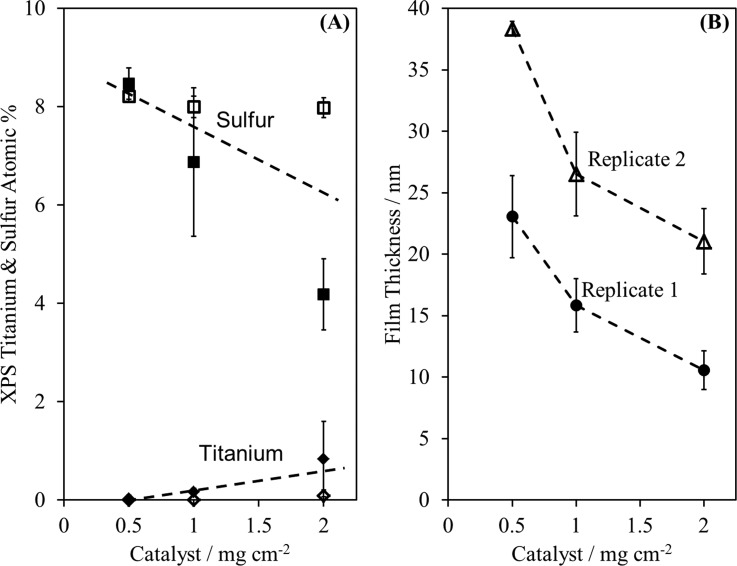

D. CuBr2 (C)

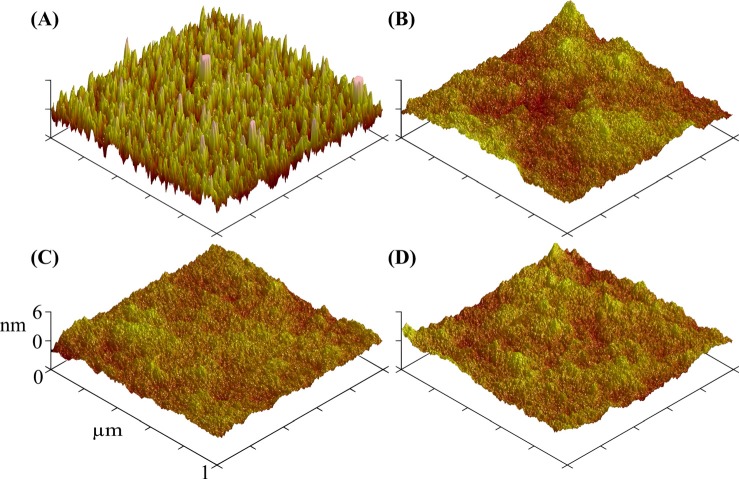

In the ANOVA regression model [Eq. (1)], CuBr2 is represented as the two-way interaction between ester ClSi reaction time and catalyst amount (). It is correlated with decreased NaSS film quality and the corresponding increased titanium signal. Both PCA and ANOVA confirm this term as significant. As previously discussed, it is more likely that the two-way interaction term is registering the significance of one or both of the main effects, which was obscured by the analyzer upgrade and/or discarded data. Having already tested ester ClSi reaction time (A) in isolation, we next studied the effect of CuBr2 amount (C) on NaSS film quality. Our hypothesis was that with increasing catalyst the number of exposed radicals, and the total time that each radical is exposed, also increases. This in turn leads to decreased reaction control resulting in nonuniform NaSS films. To test this hypothesis NaSS grafting reactions were carried out using low (−1) levels for all process variables except for CuBr2, which varied between 0.5 and 2 mg cm−2. Chemical uniformity was characterized via XPS survey and high-resolution C1s scans. Three surveys and one high-resolution scan were collected per sample. Lateral uniformity and film thickness were characterized via AFM, with three topography images obtained and three scratch tests performed per sample. Two duplicate samples were prepared per treatment, and the entire study was replicated twice resulting in a total of four samples per treatment.

The XPS composition results [Fig. 7(a)] show a trend of increasing titanium and decreasing sulfur with increasing catalyst. This suggests decreasing NaSS film thickness or uniformity with increasing CuBr2. The AFM scratch tests [Fig. 7(b)] confirm that film thickness decreases with increasing catalyst concentration, while the topography results (Fig. 8) confirm the film uniformity does not appear to be a function of CuBr2 concentration. Our hypothesized reason for the thinner films is that with increasing catalyst the number and frequency of radical activation events also increases. This leads to an increased number of termination events between neighboring polymer chains, which in turn depletes the dormant polymer state and causes a buildup of deactivator (CuBr2/bpy, in this case).5 Therefore, we recommend using the minimum amount of CuBr2 necessary, which for this system seems to be no more than 0.5 mg per nominal cm2 of initiator-functionalized surface area.

Fig. 7.

XPS titanium and sulfur composition vs CuBr2 per nominal cm2 of initiator-functionalized surface area for both replicates (A). AFM measured thicknesses vs CuBr2 per nominal cm2 of initiator-functionalized surface for both replicates (B). For both panels, data from replicate 1 and 2 are represented by closed and open symbols, respectively. These results show that NaSS film thickness decreases with increasing catalyst amount.

Fig. 8.

(Color online) Representative AFM images of NaSS films grown with 0 (a), 0.5 (b), 1 (c), and 2 mg (d) CuBr2 per nominal cm2 of initiator-functionalized surface area. Average ± standard deviation RMS roughness values for each treatment are as follows: 1.9 ± 0.1 nm (0 mg cm−2 CuBr2), 0.7 ± 0.2 nm (0.5 mg cm−2 CuBr2), 0.7 ± 0.1 nm (1 mg cm−2 CuBr2), and 0.9 ± 0.2 nm (2 mg cm−2 CuBr2).

IV. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

A 24 factorial design was performed to optimize the ARGET-ATRP grafting of NaSS from titanium. The factors varied were: (1) ester ClSi initiator reaction time; (2) grafting reaction time; (3) CuBr2 amount; and (4) reducing agent (vitamin C) amount. The factors and levels are listed in Table I. The design matrix is found in Table II. Films were characterized using XPS and the factorial design analyzed using ANOVA and PCA. The ANOVA results and regression model are found in Table III and Eq. (1). The significant factors are B (grafting reaction time; P = 4.5 10−3), AC (the two-way interaction between ester ClSi reaction time and CuBr2 amount; P = 0.02), and BD (the two-way interaction between grafting reaction time and vitamin C amount; P = 0.04). For reasons discussed above—including the possibility of the two-way interaction terms being retained due to false positives—interpretation of these results and regression model is somewhat problematic. Therefore, PCA was used to provide additional insight into the NaSS grafting process. Additional studies were done to investigate the significant effects identified by ANOVA and PCA, as well as to gain some understanding of their influence on NaSS film quality. The conclusions are as follows: (1) no chemical, structural, or morphological changes were detected with ester ClSi reaction time (A) suggesting that this effect has little discernable influence on NaSS film quality. SFG spectra show some degree of ordering in the ClSi films on the titanium surfaces, but the ClSi film quality does not improve beyond the first day of reaction time. (2) NaSS film quality decreases with grafting reaction time for both ester and amide ClSi initiators, but not for films grafted from thiol initiators on Au. This may be due to the CuBr2 corroding the titanium substrate. No decrease in film quality is observed on Au because noble metals are more resistant to corrosion. (3) In addition to potentially corroding metal surface, NaSS film thickness decreased with increasing CuBr2 concentration.

From these conclusions, we suggest using the following reaction conditions to optimize grafted film quality: (1) Shorter ATRP-initiator surface functionalization reaction times, although no deleterious effects were detected at longer times. (2) Minimum (≤ 24 h for this system) grafting reaction times. (3) Minimum (≤ 0.5 mg cm−2 for this system) CuBr2 concentration. (4) Sufficient excess of vitamin C, as no deleterious effects were detected with increasing concentrations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grant EB-002027 to NESAC/BIO. The authors thank Veronique Migonney for stimulating discussions about the preparation and biological applications of grafted NaSS films. The authors also gratefully acknowledge Linda Boyle for her helpful discussions regarding the proper handling of the XPS analyzer upgrade in the factorial design ANOVA.

References

- 1. Edmondson S., Osborne V. L., and Huck W. T. S., Chem. Soc. Rev. 33, 14 (2004). 10.1039/b210143m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhao B. and Brittain W. J., Prog. Polym. Sci. 25, 677 (2000). 10.1016/S0079-6700(00)00012-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ingall M. D. K., Honeyman C. H., Mercure J. V., Bianconi P. A., and Kunz R. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 3607 (1999). 10.1021/ja9833927 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jordan R., Ulman A., Kang J. F., Rafailovich M. H., and Sokolov J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 1016 (1999). 10.1021/ja981348l [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matyjaszewski K., Macromolecules 45, 4015 (2012). 10.1021/ma3001719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang J., Murata H., Koepsel R. R., Russell A. J., and Matyjaszewski K., Biomacromolecules 8, 1396 (2007). 10.1021/bm061236j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keefe A. J., Brault N. D., and Jiang S., Biomacromolecules 13, 1683 (2012). 10.1021/bm300399s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsugi T., Saito J., Kawahara N., Matsuo S., Kaneko H., Kashiwa N., Kobayashi M., and Takahara A., Polym. J. 41, 547 (2009). 10.1295/polymj.PJ2009034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Himmelhaus M., Eisert F., Buck M., and Grunze M., J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 576 (2000). 10.1021/jp992073e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weaver J. V. M., Bannister I., Robinson K. L., Bories-Azeau X., Armes S. P., Smallridge M., and McKenna P., Macromolecules 37, 2395 (2004). 10.1021/ma0356358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qiu J. and Matyjaszewski K., Macromolecules 30, 5643 (1997). 10.1021/ma9704222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peng C.-H., Kong J., Seeliger F., and Matyjaszewski K., Macromolecules 44, 7546 (2011). 10.1021/ma201035u [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nanda A. K. and Matyjaszewski K., Macromolecules 36, 599 (2003). 10.1021/ma021418f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jakubowski W. and Matyjaszewski K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 4482 (2006). 10.1002/anie.200600272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jakubowski W., Min K., and Matyjaszewski K., Macromolecules 39, 39 (2006). 10.1021/ma0522716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Listak J., Jakubowski W., Mueller L., Plichta A., Matyjaszewski K., and Bockstaller M. R., Macromolecules 41, 5919 (2008). 10.1021/ma800816j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Min K., Gao H., and Matyjaszewski K., Macromolecules 40, 1789 (2007). 10.1021/ma0702041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choi C.-K. and Kim Y.-B., Polym. Bull. 49, 433 (2003). 10.1007/s00289-003-0130-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen X., Randall D. P., Perruchot C., Watts J. F., Patten T. E., von Werne T., and Armes S. P., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 257, 56 (2003). 10.1016/S0021-9797(02)00014-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lei Z., Bi S., Hu B., and Yang H., Food Chem. 105, 889 (2007). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lei Z., Li Y., and Wei X., J. Solid State Chem. 181, 480 (2008). 10.1016/j.jssc.2007.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Helary G., Noirclere F., Mayingi J., Bacroix B., and Migonney V., J. Mater. Sci. - Mater. Med. 21, 655 (2010). 10.1007/s10856-009-3892-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Helary G., Noirclere F., Mayingi J., and Migonney V., Acta Biomater. 5, 124 (2009). 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kerner S., Migonney V., Pavon-Djavid G., Helary G., Sedel L., and Anagnostou F., J. Mater. Sci. - Mater. Med. 21, 707 (2010). 10.1007/s10856-009-3928-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Michiardi A., Helary G., Nguyen P. C. T., Gamble L. J., Anagnostou F., Castner D. G., and Migonney V., Acta Biomater. 6, 667 (2010). 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ciobanu M., Siove A., Gueguen V., Gamble L. J., Castner D. G., and Migonney V., Biomacromolecules 7, 755 (2006). 10.1021/bm050694+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pavon-Djavid G., Gamble L. J., Ciobanu M., Gueguen V., Castner D. G., and Migonney V., Biomacromolecules 8, 3317 (2007). 10.1021/bm070344i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vaquette C., Viateau V., Guérard S., Anagnostou F., Manassero M., Castner D. G., and Migonney V., Biomaterials 34, 7048 (2013). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Montgomery D. C., Design, Analysis of Experiments ( Wiley, New York, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wagner M. S., Tyler B. J., and Castner D. G., Anal. Chem. 74, 1824 (2002). 10.1021/ac0111311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wagner M. S., Graham D. J., Ratner B. D., and Castner D. G., Surf. Sci. 570, 78 (2004). 10.1016/j.susc.2004.06.184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wagner M. S., Graham D. J., and Castner D. G., Appl. Surf. Sci. 252, 6575 (2006). 10.1016/j.apsusc.2006.02.073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Graham D. J. and Castner D. G., Biointerphases 7, 1 (2012). 10.1007/s13758-012-0049-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Graham D. J. and Castner D. G., Mass Spectrom. 2, S0014 (2013). 10.5702/massspectrometry.S0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Foster R. N., Keefe A. J., Jiang S., and Castner D. G., J. Vac. Sci. Technol., A 31, 06F103 (2013). 10.1116/1.4819833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1116/1.4929506E-JVTAD6-33-330505 for additional statistical analysis, XPS and AFM results.

- 37. Fadeev A. Y. and McCarthy T. J., Langmuir 16, 7268 (2000). 10.1021/la000471z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Iwasaki Y. and Saito N., Colloids Surf., B 32, 77 (2003). 10.1016/S0927-7765(03)00147-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Conboy J. C., Messmer M. C., and Richmond G. L., J. Phys. Chem. 100, 7617 (1996). 10.1021/jp953616x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vidal F. and Tadjeddine A., Rep. Prog. Phys. 68, 1095 (2005). 10.1088/0034-4885/68/5/R03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guyot-Sionnest P., Superfine R., Hunt J. H., and Shen Y. R., Chem. Phys. Lett. 144, 1 (1988). 10.1016/0009-2614(88)87079-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miranda P. B. and Shen Y. R., J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 3292 (1999). 10.1021/jp9843757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Asanuma H., Noguchi H., Uosaki K., and Yu H.-Z., J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 4892 (2006). 10.1021/jp056131+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tateishi Y., Kai N., Noguchi H., Uosaki K., Nagamura T., and Tanaka K., Polym. Chem. 1, 303 (2010). 10.1039/B9PY00227H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1116/1.4929506E-JVTAD6-33-330505 for additional statistical analysis, XPS and AFM results.