Abstract

Objectives:

Surveillance drug resistance mutations (SDRMs) in drug-naive patients are typically used to survey HIV-1-transmitted drug resistance (TDR). We test here how SDRMs in patients failing treatment, the original source of TDR, contribute to assessing TDR, transmissibility and transmission source of SDRMs.

Design:

This is a retrospective observational study analyzing a Portuguese cohort of HIV-1-infected patients.

Methods:

The prevalence of SDRMs to protease inhibitors, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) in drug-naive and treatment-failing patients was measured for 3554 HIV-1 subtype B patients. Transmission ratio (prevalence in drug-naive/prevalence in treatment-failing patients), average viral load and robust linear regression with outlier detection (prevalence in drug-naive versus in treatment-failing patients) were analyzed and used to interpret transmissibility.

Results:

Prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive and treatment-failing patients were linearly correlated, but some SDRMs were classified as outliers – above (PRO: D30N, N88D/S, L90 M, RT: G190A/S/E) or below (RT: M184I/V) expectations. The normalized regression slope was 0.073 for protease inhibitors, 0.084 for NRTIs and 0.116 for NNRTIs. Differences between SDRMs transmission ratios were not associated with differences in viral loads.

Conclusion:

The significant linear correlation between prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive and in treatment-failing patients indicates that the prevalence in treatment-failing patients can be useful to predict levels of TDR. The slope is a cohort-dependent estimate of rate of TDR per drug class and outlier detection reveals comparative persistence of SDRMs. Outlier SDRMs with higher transmissibility are more persistent and more likely to have been acquired from drug-naive patients. Those with lower transmissibility have faster reversion dynamics after transmission and are associated with acquisition from treatment-failing patients.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, HIV drug resistance, mutation, protease inhibitors, reverse transcriptase inhibitors, transmission

Introduction

The prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance in drug-naive patients (drug-naive) varies across geographic regions [1–7]. To monitor transmitted drug resistance (TDR), most studies count the number of surveillance drug resistance mutations (SDRMs) in newly diagnosed [8]. This approach does not analyze transmissibility and transmission source of SDRMs. Different transmissibility of wild-type and SDRM-containing viruses has been reported [9–11]. These likely result from different reversion dynamics and fitness costs in absence of drugs. First-line treatment guidelines assume that drug-naive patients with TDR, infected directly from patients failing treatment, harbor undetected SDRMs as minority variants and suggest avoiding low genetic barrier regimens, even if DRMs against such regimens are not observed [12,13]. More treatment options could be available if it could be shown that those patients acquired TDR from other drug-naive patients. To investigate TDR, directly from treatment-failing versus onwards between drug-naive patients, most studies investigate transmission chains [14–16], which are complicated and require dense sampling. We describe an innovative approach to correlate prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive and treatment-failing patients, providing understanding of transmissibility and reversion dynamics. We use robust linear regression to measure transmissibility and source of SDRMs, which does not require dense sampling.

Methods

The protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ethical Committees of Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Ocidental (108/CES-2014) and KU Leuven, Faculty of Medicine (NH019/2015–06–01). We used a database containing anonymized patients’ clinical and HIV-1 sequence data obtained in Portugal between April 2001 and March 2013 for antiretroviral resistance testing. To ensure patients belonged to the same epidemic, analyses were limited to subtype B [17,18]. Of 3606 sequences from 3354 patients, 1685 were from drug-naive and 1921 from treatment-failing patients, using only the first (drug-naive) or last (treatment-failing) sequence per patient. Median age and sex proportion was similar in drug-naive [43 years, interquartile range (IQR) = 15 years; 75.7% males] and treatment-failing patients (48 years, IQR = 13 years; 74.1% males). Reproducibility was tested on a previously published German cohort (DE) [19].

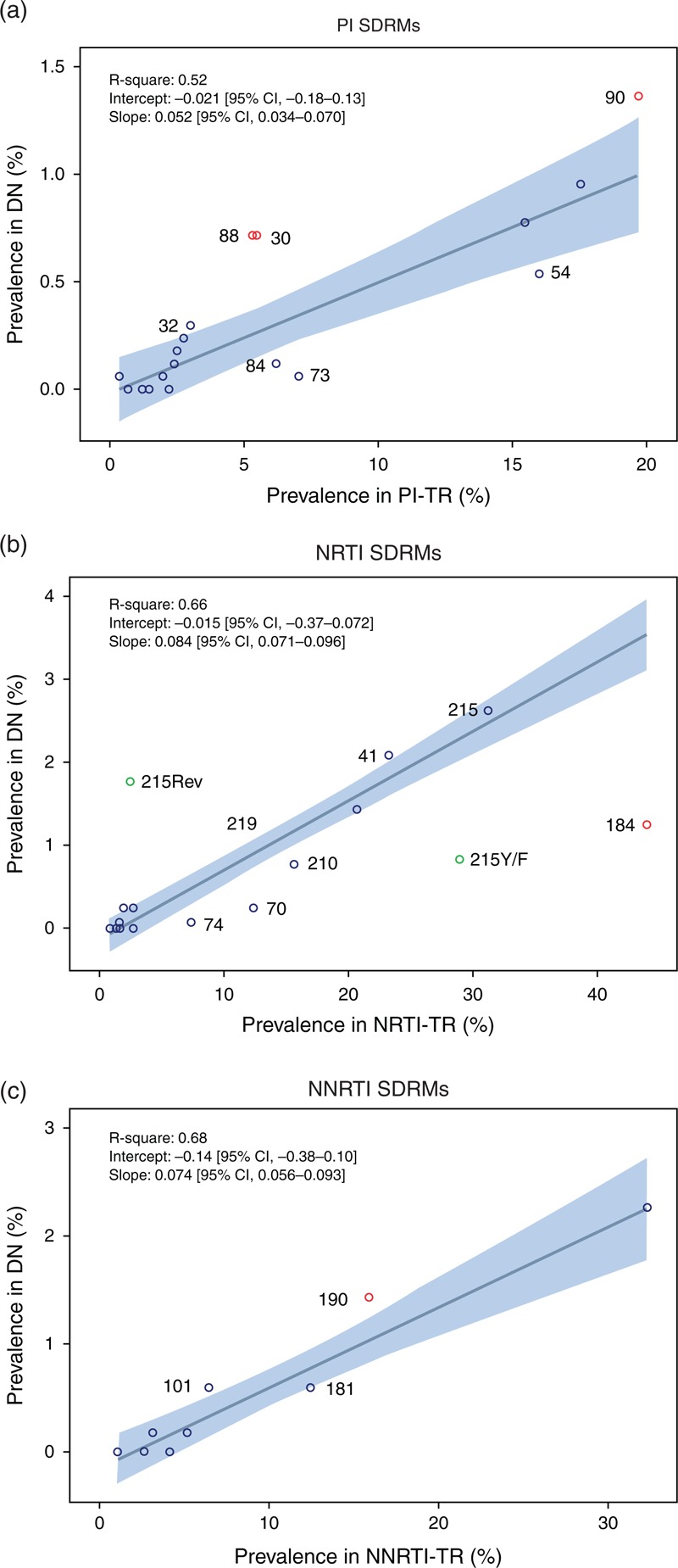

TDR mutations were those listed in ref. [8]. Drug-naive patients were patients naive for all drug classes, whereas treatment-failing patients were patients experienced with the drug class of interest. Prevalence in treatment-failing patients is presented per drug class (Fig. 1) or, for comparison between drug classes, normalized for the complete treated population (Table 1, Fig. S1, for Portugal and S2, for DE).

Fig. 1.

Robust regression model for the Portuguese cohort, relating prevalence of SDRMs (codon position) in treatment-failing patients per drug class versus prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive patients.

The linear regression line is shown together with the 95% CI, slope, intercept and R2. SDRMs above or below the 95% CI are labeled with codon position; robust outliers (see Table S1, ) are shown as red circles. (a) Prevalence of each protease inhibitor SDRM in protease inhibitor-treatment-failing patients [i.e. (#protease inhibitor SDRMs in protease inhibitor-treatment-failing patients)/# protease inhibitor-treatment-failing patients, see Table 1] versus prevalence of each protease inhibitor SDRM in drug-naive patients i.e. (#protease inhibitor SDRMs in drug-naive)/# drug-naive patients. (b) Prevalence of each NRTI SDRM in NRTI-treatment-failing patients versus prevalence of each NRTI SDRM in drug-naive patients. T215Y/F and T215Rev are shown in green but were taken together (T215) for the linear regression. (c) Prevalence of each NNRTI SDRM in NNRTI-treatment-failing patients versus prevalence of each NNRTI SDRM in drug-naive patients. CI, confidence interval; DN, drug-naive individuals; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTI-TR, patients failing a NNRTI-containing treatment; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NRTI-TR, patients failing a NRTI-containing treatment; SDRM, surveillance drug resistance mutations; PI, protease inhibitor; PI-TR, patients failing a PI-containing treatment.

Table 1.

Overview of the SDRMs identified in the Portuguese cohort, at each position for each drug class with prevalence and transmission ratios.

| Protease inhibitor | ||||

| Protease inhibitor-SDRM | Prevalence (%) in drug-naive patients (N = 1685) (95% CI) | Prevalence (%) in protease inhibitor-treatment-failing patients (N = 1352) (95% CI) | Normalized prevalence (%) in treatment-failing patients (N = 1921) (95% CI) | Transmission ratio |

| 83D | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) (N = l) | 0.4 (0.1–0.9) (N = 5) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) (N = 5) | 0.2 |

| 88D/S | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) (N = 12) | 5.3 (4.2-S.7) (N = 72) | 3.7 (2.9–4.7) (N = 72) | 0.1 |

| 30N | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) (N = 12) | 5.5 (4.3-S.8) (N = 74) | 3.9 (3.0–4.8) (N = 74) | 0.1 |

| 32I | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) (N = 5) | 3.0 (2.2–4.1) (N = 41) | 2.1 (1.5–2.9) (N = 41) | 0.1 |

| 24I | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) (N = 4) | 2.7 (1.9–3.8) (N = 37) | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) (N = 37) | 0.1 |

| 85V | 0.2 (0.0–0.5) (N = 3) | 2.5 (1.7–3.5) (N = 34) | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) (N = 34) | 0.1 |

| 90M | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) (N = 23) | 19.7 (17.6–21.9) (N = 266) | 13.8 (12.3–15.5) (N = 266) | 0.1 |

| 46I/L | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) (N = 16) | 17.5 (15.5–19.7) (N = 237) | 12.3 (10.9–13.9) (N = 237) | 0.1 |

| 53L/Y | 0.1 (0.0–0.4] (N = 2) | 2.4 (1.6–3.3) (N = 32) | 1.7 (1.1–2.3) (N = 32) | 0.1 |

| 82A/C/F/L/M/S/T | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) (N = 13) | 15.5 (13.5–17.5) (N = 209) | 10.8 (9.5–12.4) (N = 209) | 0.1 |

| 54A/L/M/S/T/V | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) (N = 9) | 16.0 (14.1–18.0) (N = 216) | 11.2 (9.9–12.7) (N = 216) | 0.0 |

| 48M/V | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) (N = l) | 2.0 (1.3–2.9) (N = 27) | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) (N = 27) | 0.0 |

| 84V | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) (N = 2) | 6.2 (5.0–7.6) (N = 84) | 4.4 (3.5–5.4J (N = 84) | 0.0 |

| 73A/C/S/T | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) (N = 1) | 7.0 (5.7–8.5) (N = 95) | 4.9 (4.0–6.0) (N = 95) | 0.0 |

| 23I | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 0.7 (0.3–1.3) (N = 9) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) (N = 9) | 0.0 |

| 47A/V | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 2.2 (1.5–3.2) (N = 30) | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) (N = 30) | 0.0 |

| 50L/V | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) (N = 16) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) (N = 16) | 0.0 |

| 76V | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) (N = 20) | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) (N = 20) | 0.0 |

| Any protease inhibitor-SDRM | 3.5 (2.7–4.5) (N = 59) | 38.3 (35.7–41.0) (N = 518) | 27.0 (25.0–29.0) (N = 518) | |

| NRTI | ||||

| NRTI-SDRM | Prevalence (%) in drug-naive patients (N = 1685) (95% CI) | Prevalence (%) in NRTI-treatment-failing patients (N = 1920) (95% CI) | Normalized prevalence (%) in treatment-failing patients (N = 1921) (95% CI) | Transmission ratio |

| 215rev | 1.8 (1.2–2.5) (N = 30) | 2.4 (1.8–3.2) (N = 47) | 2.4 (1.8–3.2) (N = 47) | 0.7 |

| 75A/M/S/T | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) (N = 4) | 2.0 (1.4–2.7) (N = 38) | 2.0 [1.4–2.7) (N = 38) | 0.1 |

| 219E/N/Q/R | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) (N = 21) | 13.8 (12.2–15.4) (N = 264) | 13.7 (12.2–15.4) (N = 264) | 0.1 |

| 41L | 2.1 (1.5–2.9) (N = 35) | 23.3 (21.4–25.2) (N = 447) | 23.3 (21.4–25.2) (N = 447) | 0.1 |

| 69D | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) (N = 4) | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) (N = 52) | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) (N = 52) | 0.1 |

| 215Y/F + rev | 2.6 (1.9–3.5) (N = 44) | 31.3 (29.2–33.4) (N = 600) | 31.2 (29.2–33.4) (N = 600) | 0.1 |

| 67E/G/N | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) (N = 24) | 20.7 (18.9–22.6) (N = 398) | 20.7 (18.9–22.6) (N = 398) | 0.1 |

| 210W | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) (N = 13) | 15.6 (14.0–17.3) (N = 300) | 15.6 (14.0–17.3) (N = 300) | 0.0 |

| 151M | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) (N = 1) | 1.7 (1.1–2.3) (N = 32) | 1.7 (1.1–2.3) (N = 32) | 0.0 |

| 215Y/F | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) (N = 14) | 28.8 (26.8–30.9) (N = 553) | 28.8 (26.8–30.9) (N = 553) | 0.0 |

| 184I/V | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) (N = 21) | 44.0 ((41.7–46.2) (N = 844) | 43.9 (41.7–46.2) (N = 844) | 0.0 |

| 70E/R | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) (N = 4) | 12.4 (11.0–14.0) (N = 238) | 12.4 (10.9–13.9) (N = 238) | 0.0 |

| 74I/V | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) (N = l) | 7.4 (6.3–8.7) (N = 142) | 7.4 (6.3–8.7) (N = 142) | 0.0 |

| 65R | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) (N = 52) | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) (N = 52) | 0.0 |

| 77L | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) (N = 17) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) (N = 17) | 0.0 |

| 115F | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) (N = 31) | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) (N = 31) | 0.0 |

| 116Y | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) (N = 26) | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) (N = 26) | 0.0 |

| Any NRTI-SDRM | 5.0 (4.0–6.2) (N = 85) | 61.1 (58.9–63.3) (N = 1174) | 61.1 (58.9–63.3) (N = 1174) | |

| NNRTI | ||||

| NNRTI-SDRM | Prevalence in drug-naive patients (N = 1685) (95% CI) | Prevalence (%) in NNRTI-treatment-failing patients (N = 1237) (95% CI) | Normalized prevalence (%) in treatment-failing patients (N = 1921) (95% CI) | Transmission ratio |

| 101E/P | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) (N = 10) | 6.5 (5.2–8.0) (N = 80) | 4.2 (3.3–5.2) (N = 80) | 0.1 |

| 190A/E/S | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) (N = 24) | 15.6 (13.6–17.7) (N = 193) | 10.0 (8.7–11.5) (N = 193) | 0.1 |

| 103N/S | 2.3 (1.6–3.1) (N = 38) | 32.3 (29.7–34.9) (N = 399) | 20.8 (19.0–22.7) (N = 399) | 0.1 |

| 225H | 0.2 [0.0–0.5) (N = 3) | 3.2 (2.3–4.3) (N = 39) | 2.0 (1.4–2.8) (N = 39) | 0.1 |

| 181C/I/V | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) (N = 10) | 12.4 (10.7–14.4) (N = 154) | 8.0 (6.8–9.3) (N = 154) | 0.0 |

| 188C/H/L | 0.2 (0.0–0.5) (N = 3) | 5.2 (4.0–6.6) (N = 64) | 3.3 (2.6–4.2) (N = 64) | 0.0 |

| 100I | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 4.1 (3.1–5.4) (N = 51) | 2.7 (1.9–3.5) (N = 51) | 0.0 |

| 106A/M | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 2.7 (1.8–3.7) (N = 33) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) (N = 33) | 0.0 |

| 230L | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) (N = 0) | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) (N = 13) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) (N = 13) | 0.0 |

| Any NNRTI-SDRM | 4.3 (3.4–5.4) (N = 73) | 57.8 (55.0–60.6) (N = 715) | 37.2 (35.1–39.4) (N = 715) | |

Bold entries indicate an SDRM located above or below the 95% CI in the robust linear regression (Fig. 1). Variants at a single position are pooled (e.g. 46I/L). CI, confidence interval; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; SDRM, surveillance drug resistance mutations.

For each SDRM, we evaluated two measures of transmissibility: transmission ratio (Table 1), prevalence in drug-naive patients divided by prevalence in patients failing treatment containing that drug class; regression model for each drug class, correlating SDRMs prevalence in drug-naive and treatment-failing patients, with outlier detection (Fig. 1 and S1 for Portugal, Fig. S2, for DE).

To evaluate the viral load effect, we correlated viral load of patients with SDRMs and transmission ratio for those SDRMs. Analyses were performed considering viral load of drug-naive, treatment-failing (Fig. S3, ) or drug-naive + treatment-failing patients containing SDRMs.

For statistical analyses, SAS, R and Rpy2 interface for Python were used [20–23]. Outliers were identified with robust linear regression (ROBUSTREG, SAS) assuming prevalence in treatment-failing patients as fixed and independent.

Results

The prevalence of TDR in Portugal was 10.0% (95% confidence interval (CI): 8.6–11.5], whereas 67.7% of treatment-failing patients [65.5–69.8] carried SDRMs. Most TDR was single [7.4%, (6.2–8.8%); 5.4% singletons], followed by double [2.2% (1.6–3.0%)] and triple class resistance [0.4% (0.1–0.8%)]. In treatment-failing patients, 18.6% (16.9–20.4%) had single class resistance, 1.9% singletons; 38.4% (36.2–40.6%) double and 10.7% (9.3–12.1%) triple class resistance. SDRMs with highest prevalence in drug-naive patients were L90 M (1.4%) for protease inhibitors, T215Y/F + Rev (Rev = C, D, E, I, S, V) (2.6%) for nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, (NRTIs) and K103N/S (2.3%) for nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, (NNRTIs). In treatment-failing patients, SDRMs with highest prevalence were L90 M (19.7%), M184I/V (44.0%) and K103N/S (32.3%). Highest transmission ratios were observed for N83D (0.165), N88D/S (0.134) and D30N (0.130) for protease inhibitors; T215Rev (0.727) (for T215Y/F was 0.029) and V75A/M/S/T (0.120) for NRTIs; and K101E/P (0.092) and G190A/E/S (0.091) for NNRTIs (Table 1).

We found a significant linear correlation between prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive versus treatment-failing patients, indicating that prevalence in drug-naive patients can be predicted from prevalence in treatment-failing patients from the same epidemic. In the Portugal regression model [Fig. 1 (drug class specific) and S1 (normalized)], the R2 ranged between 0.52 (protease inhibitors) and 0.68 (NNRTIs). After normalizing for treatment, the regression slope was higher for NNRTIs (0.116), followed by NRTIs (0.084) and protease inhibitors (0.073) (Fig. S1, ). In each class-specific analysis, some SDRMs were classified as outliers: for protease inhibitors, D30N, N88D/S, and L90 M were above; for NRTIs, M184I/V was below; and for NNRTIs G190A/E/S was above the regression line (Table S1, ).

In the normalized regression model for DE [19] (Fig. S2, ), the slope was also higher for NNRTIs (0.08) followed by NRTIs (0.07). Outliers and positioning of mutations were consistent with Portugal for NRTIs (Fig. S2B, ) and for NNRTIs (Fig. S2C, ). For NRTIs, K219N and T215rev were consistently above, whereas K70E, M184I/V, L210W and T215Y/F were below the CI (see Fig. 1B and S2B, for outlier classification). Mutations M41L (above) and L74I/V (below) were outside the CI for Portugal but not for DE, and T69N (above) and K65R (below) were outside the CI for DE but not for Portugal. For NNRTIs, Y181C/I/V was below the CI and G190A/E/S was above the CI in both cohorts. K101P was above the CI for Portugal and not for DE and V106I below the CI for DE but not Portugal. There were no SDRMs significantly on opposite sides of the regression line when comparing cohorts. For protease inhibitors (Fig. 1A and S2A, ), preliminary analysis showed important differences between cohorts that we could not analyze further, as access to DE data was limited (only DRMs with a prevalence >0.3% were reported in [19]). It has to be noted that in the German cohort, all subtypes were considered together, whereas we only analyzed the subtype B epidemic. Additionally, other SDRMs may have spread in transmission clusters among drug-naive.

We found no significant correlation between the transmission ratio of specific SDRMs and the viral load of individuals carrying such SDRMs in samples taken at most 30 days before or after the resistance test (Figure S3, ). The Wilcoxon rank sum test showed no significant differences between the viral load of treatment-failing patients failing different drug classes.

Discussion

We describe a simple and innovative method that compares the prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive patients with its prevalence in treatment-failing patients. We tested two approaches: SDRM transmission ratios and robust linear regression comparing prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive and treatment-failing patients. We analyzed Portuguese subtype B patients; thus, drug-naive and treatment-failing patients belong to the same epidemic [24], and confirmed the approach using a German cohort [19]. Yet, specificity and reproducibility should be tested in more cohorts.

SDRM transmission ratios were high for SDRMs with high transmissibility (e.g. 0.727 for T215Rev, Table 1); however, precision was low for SDRMs with low prevalence in treatment-failing patients: N83D has a high transmission ratio (0.165) but was only found in one drug-naive and five treatment-failing patients, with large CI. Thus, transmission ratios can only give reliable indications of transmissibility for mutations highly prevalent in treatment-failing patients.

Robust regression indicated the prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive and treatment-failing patients to be linearly correlated (Fig. 1), suggesting that prevalence in treatment-failing patients can be used for surveillance and predicts TDR levels. Our model can be analyzed:

First, comparing regression slopes between drug classes, as an indication of the overall transmissibility of DRMs of one drug class compared with others. Although faster reversion dynamics result in reduced slopes, increased onward transmission among drug-naive patients results in steeper slopes. However, as the slope also varies according to cohort-specific treatment strategies, we built an additional model normalizing prevalence in treatment-failing patients to the total population failing treatment (Fig. S1, ). If SDRMs would not affect fitness in absence of drugs, the normalized slope should be similar between drug classes. Differences can then be explained by different reversion dynamics of SDRMs to different drug classes, impacting rates of onward transmission. In both cohorts, the NNRTI-normalized slope is higher than the NRTI's, consistent with higher persistence of NNRTI mutations [25]. We found, however, that the protease inhibitor model may be more cohort-dependent.

Second, outlier detection within drug class: an SDRM found more often in drug-naive patients than expected from prevalence in treatment-failing patients, meaning it is found above the regression line, suggests that its prevalence in drug-naive patients increased by onward transmission among drug-naive patients, indicating higher transmissibility than other DRMs to the same drug class. This mutation has a lower reversion rate after transmission because of lower fitness cost. If the SDRM is found below the regression line, meaning it is occurs less frequently in drug-naive patients than expected from its prevalence in treatment-failing patients, it is transmitted less often and/or reverses faster because of higher fitness cost in absence of the drug.

Our results are consistent with other studies: M184I/V has been shown to have low persistence after transmission to drug-naive patients; G190A has been shown to have high persistence [26–29]. We show here that D30N, N88D/S and L90 M also have high transmissibility and that other SDRMs have higher (M41L, T215Rev and K219E/N/Q/R for NRTIs and K101E/P for the NNRTIs) or lower transmissibility (K70E/R, L74I/V, and T215Y/F for NRTIs; Y181C/I/V for NNRTIs and I84 V and I54A/L/M/S/T/V for protease inhibitors) compared with other mutations of the same drug class. T215Rev and T215Y/F are above and below the regression line respectively, supporting our model, as T215Y/F has a fitness cost in absence of drug and reverts after transmission into one of the T215Rev mutants with less onward transmission of T215Y/F between drug-naive patients [30]. Our findings are confirmed with the German cohort, wherein mostly the same mutations fall above or below the regression line.

This is the first time the correlation of SDRM prevalence in treatment-failing and drug-naive patients is used to make claims on transmissibility and source of acquisition of TDR. Other studies investigating transmission ratios only considered treatment-failing patients as source of SDRMs [9,11]. Our approach enables identification of SDRMs for which drug-naive patients are a likely additional source.

Our results support that for first-line treatment strategies, prevalence of SDRMs in local treatment-failing patients should be considered given the linear correlation with prevalence in drug-naive patients. This is more practical than only counting SDRMs in drug-naive patients because: the prevalence of SDRMs in treatment-failing patients is higher than in drug-naive patients and therefore the CI is smaller; many drug-naive patients have not been diagnosed and therefore sampled; although most treatment-failing patients are tested for drug resistance immediately at treatment failure, in many countries, most drug-naive patients are either not tested or tested only just before starting treatment when eventual reversion already took place. Our approach is therefore especially useful for resource-limited settings.

In conclusion, correlating the prevalence of SDRMs in drug-naive and treatment-failing patients gives a refined view of the transmission dynamics, persistence, viral fitness and source of TDR, which could help public health and strategic measures to avoid increasing TDR. Future efforts should include the development of more sophisticated statistical models to address the uncertainty associated with less frequent SDRMs.

Acknowledgements

Authors’ contributions: R.W.: database implementation, data analysis, figures, data interpretation, writing; K.T.: data interpretation, writing; Mónica Eusébio: data analysis; J.A.: data interpretation, writing; R.C.: data collection, data curation, database implementation; P.G.: data collection, data curation; M.S.: analysis design, writing; A-M.V.: study design, data interpretation, figures, writing; A.A.: study design, data analysis, data interpretation, figures, writing; Portuguese HIV-1 Resistance Study Group: data collection. Members of the Portuguese HIV-1 Resistance Study Group:

Kamal Mansinho, Ana Cláudia Miranda, Isabel Aldir, Fernando Ventura, Jaime Nina, Fernando Borges, Emília Valadas, Manuela Doroana, Francisco Antunes, Maria João Aleixo, Maria João Águas, Júlio Botas, Teresa Branco, José Vera, Inês Vaz Pinto, José Poças, Joana Sá, Luis Duque, António Diniz, Ana Mineiro, Flora Gomes, Carlos Santos, Domitília Faria, Paula Fonseca, Paula Proença, Luís Tavares, Cristina Guerreiro, Jorge Narciso, Telo Faria, Eugénio Teófilo, Sofia Pinheiro, Isabel Germano, Umbelina Caixas, Nancy Faria, Ana Paula Reis, Margarida Bentes Jesus, Graça Amaro, Fausto Roxo, Ricardo Abreu and Isabel Neves.

This project was funded through: Research Council KU Leuven: GOA/10/09 MaNet, CoE PFV/10/016 SymBioSys; FWO grant G069214N and KAN 1.5.249.12; iMinds Medical Information Technologies SBO 2014, ICON b-SLIM; Collaborative HIV and Anti-HIV Drug Resistance Network (CHAIN, grant Health-F3–2009–223131, European Community's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007–2013); BEST HOPE: Bio-Molecular and Epidemiological Surveillance of HIV Transmitted Drug Resistance, Hepatitis Co-Infections and Ongoing Transmission Patterns in Europe (project funded through HIVERA: Harmonizing Integrating Vitalizing European Research on HIV/Aids, grant 249697); US National Science Foundation: DMS 1264153; L’Oréal Portugal Medals of Honor for Women in Science 2012 (financed through L’Oréal Portugal, Comissão Nacional da Unesco and Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia). A.B.A. received a postdoc fellowship by the Fundação de Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH/BPD/65605/2009). K.T. receives a FWO postdoctoral fellowship. The funding sources had no role in the writing of the manuscript or on the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Vercauteren J, Wensing AMJ, van de Vijver DA, Albert J, Balotta C, Hamouda O, et al. Transmission of drug-resistant HIV-1 is stabilizing in Europe. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:1503–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wensing AMJ, van de Vijver DA, Angarano G, Asjö B, Balotta C, Boeri E, et al. Prevalence of drug-resistant HIV-1 variants in untreated individuals in Europe: implications for clinical management. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frentz D, Boucher C a B, van de Vijver DA. Temporal changes in the epidemiology of transmission of drug-resistant HIV-1 across the world. AIDS Rev 2012; 14:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett DE, Myatt M, Bertagnolio S, Sutherland D, Gilks CF. Recommendations for surveillance of transmitted HIV drug resistance in countries scaling up antiretroviral treatment. Antivir Ther 2008; 13 Suppl 2:25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth CL, Geretti AM. Prevalence and determinants of transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance in HIV-1 infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 59:1047–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stadeli KM, Richman DD. Rates of emergence of HIV drug resistance in resource-limited settings: a systematic review. Antivir Ther 2013; 18:115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhee S-Y, Blanco JL, Jordan MR, Taylor J, Lemey P, Varghese V, et al. Geographic and temporal trends in the molecular epidemiology and genetic mechanisms of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance: an individual-patient- and sequence-level meta-analysis. PLOS Med 2015; 12:e1001810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett DE, Camacho RJ, Otelea D, Kuritzkes DR, Fleury H, Kiuchi M, et al. Drug resistance mutations for surveillance of transmitted HIV-1 drug-resistance: 2009 update. PLoS One 2009; 4:e4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leigh Brown AJ, Frost SDW, Mathews WC, Dawson K, Hellmann NS, Daar ES, et al. Transmission fitness of drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus and the prevalence of resistance in the antiretroviral-treated population. J Infect Dis 2003; 187:683–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blower SM, Aschenbach AN, Gershengorn HB, Kahn JO. Predicting the unpredictable: transmission of drug-resistant HIV. Nat Med 2001; 7:1016–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Mendoza C, Rodriguez C, Corral A, del Romero J, Gallego O, Soriano V. Evidence for differences in the sexual transmission efficiency of HIV strains with distinct drug resistance genotypes. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1231–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vandamme A-M, Camacho RJ, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, de Luca A, Palmisano L, Paraskevis D, et al. European recommendations for the clinical use of HIV drug resistance testing: 2011 update. AIDS Rev 2011; 13:77–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/Adultand AdolescentGL.pdf [Accessed 9 August 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yerly S, Junier T, Gayet-Ageron A, Amari EB, von Wyl V, Günthard HF, et al. The impact of transmission clusters on primary drug resistance in newly diagnosed HIV-1 infection. AIDS 2009; 23:1415–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Audelin AM, Gerstoft J, Obel N, Mathiesen L, Laursen A, Pedersen C, et al. Molecular phylogenetics of transmitted drug resistance in newly diagnosed HIV Type 1 individuals in Denmark: a nation-wide study. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 2011; 27:1283–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drescher SM, von Wyl V, Yang W-L, Böni J, Yerly S, Shah C, et al. Treatment-naive individuals are the major source of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance in men who have sex with men in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alcantara LCJ, Cassol S, Libin P, Deforche K, Pybus OG, Van Ranst M, et al. A standardized framework for accurate, high-throughput genotyping of recombinant and nonrecombinant viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:W634–W642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Oliveira T, Deforche K, Cassol S, Salminen M, Paraskevis D, Seebregts C, et al. An automated genotyping system for analysis of HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics 2005; 21:3797–3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt D, Kollan C, Fätkenheuer G, Schülter E, Stellbrink H-J, Noah C, et al. Estimating trends in the proportion of transmitted and acquired HIV drug resistance in a long term observational cohort in Germany. PLoS One 2014; 9:e104474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAS Institute Inc. Business analytics and business intelligence software. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.;. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. 2013. http://www.r-project.org/ [Accessed 10 August 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gautier and Rpy2 contributors. Rpy2 (version 2.4). 2014. http://rpy.sourceforge.net/rpy2/doc-2_4/html/index.html [Accessed 10 August 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Rossum G, Drake FL. Python Software Foundation. 2001. http://www.python.org/ [Accessed 2 June 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palma C, Araújo F, Duque V, Borges F, Paixão MT, Camacho R. Molecular epidemiology and prevalence of drug resistance-associated mutations in newly diagnosed HIV-1 patients in Portugal. Infect Genet Evol 2007; 7:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Béthune M-P. Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), their discovery, development, and use in the treatment of HIV-1 infection: a review of the last 20 years (1989-2009). Antiviral Res 2010; 85:75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro H, Pillay D, Cane P, Asboe D, Cambiano V, Phillips A, et al. Persistence of HIV-1 transmitted drug resistance mutations. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:1459–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang W-L, Scherrer A, Yerly S, Böni J, Klimkait T, Aubert V, et al. Prevalence of transmitted drug resistance and relation to mean population viral load of treatment failing patients: a 16-year analysis within the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS). Antivir Ther 2013; 18 Suppl 1:A21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang W-L, Kouyos RD, Böni J, Yerly S, Klimkait T, Aubert V, et al. Persistence of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance mutations associated with fitness costs and viral genetic backgrounds. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11:e1004722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang WL, Kouyos R, Scherrer AU, Boni J, Shah C, Yerly S, et al. Assessing the paradox between transmitted and acquired HIV type 1 drug resistance mutations in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study From 1998 to 2012. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolling D, Sabin C, Delpech V, Smit E, Pozniak A, Asboe D, et al. Time trends in drug resistant HIV-1 infections in the United Kingdom up to 2009: multicentre observational study. BMJ 2012; 345:e5253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.