Abstract

Background

Combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) suppresses viral replication in HIV-infected children. The growth of virologically suppressed children on ART has not been well documented. We aimed to develop dynamic reference curves for weight-for-age z scores (WAZ) and height-for-age z scores (HAZ).

Methods

Children aged <11 years at ART initiation with continuously undetectable viral loads (<400 copies/ml) treated at seven South African ART programs with routine viral load monitoring were included. We used multilevel models to define trajectories of WAZ and HAZ up to 3 years and developed a web application to monitor trajectories in individual children.

Results

A total of 4,876 children were followed for 7,407 person-years. Analyses were stratified by baseline z-scores and age, which were the most important predictors of growth response. The youngest children showed the most pronounced increase in weight and height initially but catch-up growth stagnated after 1–2 years. Three years after starting ART, WAZ ranged from −2.2 (95% Prediction interval −5.6 to 0.8) in children with baseline age >5 years and z-score <−3 to 0.0 (−2.7 to 2.4) in children with baseline age <2 years and WAZ >−1. For HAZ the corresponding range was −2.3 (−4.9 to 0.3) in children with baseline age>5 years and z-score <−3 to 0.3 (−3.1 to 3.4) in children with baseline age 2–5 years and HAZ >−1.

Conclusions

We have developed an online tool to calculate reference trajectories in fully suppressed children. The web application could help to define ‘optimal’ growth response and identify children with treatment failure.

Keywords: HIV, antiretroviral therapy, growth

Measuring a child’s weight and height over time and comparing it to a reference is a simple way of assessing his or her growth and health. In HIV-infected children in settings with few resources, growth monitoring is used to identify children eligible for antiretroviral therapy (ART) and weight and height trajectories are often the only information on whether a child is responding to ART 1,2,3.

Data on the association between growth and virologic response to ART are however conflicting 4. Some studies showed that virologic control leads to improved growth, while no associations were found in others 3,5. Studies from Malawi 6 and Uganda 7 reported that undernourished and stunted children often do not reach normal weight-for-age (WAZ) and height-for-age (HAZ) scores under ART. However, virologic response was not assessed in these studies and the growth trajectories in African HIV-infected children with suppressed viral replication are not well defined. In contrast, children from Europe and the US, where regular viral load monitoring is used, reached normal values within two years of initiating therapy 8.

African settings differ with regard to many factors related to growth: children generally start ART at an age of 5 to 6 years 9, often with more advanced disease. Detrimental environmental factors such as co-infections, under-nutrition and food insecurity are common 10,11. Using data from the large paediatric IeDEA Southern Africa (IeDEA-SA) collaboration we aimed to describe growth in children with consistently suppressed HIV viremia, to derive reference standards of z-score trajectories and to make these available in a web application that displays expected growth up to three years on ART for individual children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

International epidemiological Databases to Evaluate AIDS

IeDEA-SA is a collaboration of 24 ART programs in six countries in Southern Africa (www.iedea-sa.org) 12. Data are collected at ART initiation (baseline) and follow-up visits using standardized instruments. All sites have ethical approval to collect data and participate in IeDEA-SA. In the present study we used the data merged up to the first of January 2014 and included seven IeDEA-SA sites with at least 100 children that had started ART in South Africa, the only country within the IeDEA-SA collaboration where viral load was routinely monitored. Anthropometric measurements were generally scheduled to be done every 4–12 weeks. Viral loads were measured according to the South African guidelines as follows: semi-annually prior to 2010 and then from 2010–2012 at 6 and 12 months after ART initiation and then yearly.

These primary sites include the Khayelitsha ART Program, McCord Hospital, Red Cross Children's Hospital, Hlabisa HIV Care and Treatment Program, Harriet Shezi Clinic, Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital and Tygerberg Academic Hospital. An eighth site (Kheth’Impilo) which joined IeDEA only recently was used for model validation only.

Eligibility Criteria and Definitions

We included ART-naïve children aged <11 years who initiated treatment with at least three antiretroviral drugs and had undetectable viral load measurements only during the first three years on ART (all viral load values <400 copies/ml). Children did not need to have three years of follow-up to be included in the analysis. We included children who died or transferred-out during follow-up on ART. We excluded children without any anthropometric measurement after start of ART and children who were transferred from another site. A child was considered lost to follow-up if the time between the last visit and the closing date of the cohort was longer than 6 months. Weight and height measurements were converted to age- and sex-adjusted z-scores using the WHO reference population 2007 13. Underweight was defined as weight-for-age (WAZ) <–2 and stunting as height-for-age (HAZ) <–2. We took weight and height measurements and CD4 cell counts closest to the starting date of ART (−6 months/+1week) as baseline values. Immunodeficiency was defined as in the WHO case definitions of HIV 14.

Statistical analysis and modelling

The analysis was conducted using data from all 7 primary sites. The WAZ and HAZ z-score trajectories were analyzed using second order fractional polynomials 15. The same approach was used in an earlier study in Malawi 2. We used a model including all patients to determine which variables were most predictive of anthropometric trajectories and then stratified the analysis by these variables. In each stratum the best fitting second order fractional polynomial was selected based on the deviance criterion 15. Separate analyses were performed for the different strata. No interaction terms were included. We then extended the model to a Bayesian multi-level model 16 taking into account between cohort and between patient variability. The model fit was visually assessed by plotting the 95% prediction intervals and the observed trajectories for individual children. We assessed the model for over-fitting by randomly splitting the data into a training data set (90% of patients) and a test data set (10% of patients). We performed the analysis on the training set and assessed how many measurements of the test dataset were within the 95% prediction interval.

We validated the model using data from the independent cohort (Kheth’Impilo) and checked how many measurements of the validation data were within the 95% prediction interval. We report all validation results after 1 and 3 years of follow-up.

Based on the predictive distribution of growth trajectories obtained from the training data set, a web application was developed. The joint predictive distribution of location and scale parameters was approximated by a normal inverse Gamma distribution and served as the prior distribution for the growth trajectories of a new child. Available anthropometric measurements were used to update the prior as new measurements become available. The growth trajectories for a given child were then predicted using this prior distribution and past z-scores (for more details see http://iedea-sa.org). All analyses were performed in R version 3.0.2 17, Stata version 11 18 and WinBUGS version 1.4.3 19.

RESULTS

Study population and baseline characteristics

Of 12,476 children followed up in the 7 primary sites, 7,130 (57.1%) children had continuously undetectable viral load, and 5,423 had a weight and/or height measurement at the start of ART. Among these, 4,876 were randomly selected for the training dataset and 547 for the test dataset (Figure S1). The number of children included in analyses ranged from 74 children from Hlabisa in KwaZulu-Natal to 1,944 children from the Harriet Shezi clinic in Soweto. The median age of the children was 3.7 years and about half (2440 children; 50.0%) were female (Table 1). At baseline most children (4,871 children; 99.9%) had a weight measurement, and 3,340 children (68.5%) had a height measurement. A substantial proportion of children with measurements were underweight (1,805 children; 37.1%), stunted (1,842; 55.1%) and had evidence of severe immunodeficiency at baseline (1,831; 51.0%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of children starting antiretroviral therapy.

| Characteristic | All children |

Weight-for- age analysis |

Height-for- age analysis |

Validatio n data |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=4,876 | N=4,871 | N=3,340 | N=480 | ||

| Site | |||||

| Harriet Shezi, Soweto | 1,944 | 1,942 | 1,907 | - | |

| Khayelitsha, Cape Town | 980 | 979 | 128 | - | |

| Red Cross, Cape Town | 631 | 631 | 86 | - | |

| Tygerberg, Cape Town | 162 | 161 | 111 | - | |

| McCord, Durban | 689 | 689 | 683 | - | |

| Hlabisa, Kwa Zulu Natal | 74 | 74 | 56 | - | |

| Rahima Moosa, Johannesburg | 396 | 395 | 369 | - | |

| Khethimpilo, Cape Town | - | - | - | 480 | |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 3.7 (1.6–6.3) | 3.7 (1.6–6.3) | 4.1 (1.6–6.6) | 5.6 (3.4–7.6) | |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||

| <2 years | 1,679 (34.4) | 1,676 (34.4) | 1,143 (34.2) | 81 (16.9) | |

| 2 to 5 years | 1,253 (25.7) | 1,251 (25.7) | 818 (24.5) | 113 (23.5) | |

| 6 to 10 years | 1,944 (39.9) | 1,944 (39.9) | 1,379 (41.3) | 286 (59.6) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 2,440 (50) | 2,440 (50.1) | 1,669 (50) | 248 (51.7) |

| Weight-for-age z-score, n (%) | |||||

| < −3 | 946 (19.4) | 946 (19.4) | 748 (22.4) | 261 (54.4) | |

| −3 to < −2 | 859 (17.6) | 859 (17.6) | 653 (19.6) | 121 (25.2) | |

| −2 to < −1 | 1286 (26.4) | 1286 (26.4) | 883 (26.5) | 59 (12.3) | |

| >=−1 | 1780 (36.5) | 1780 (36.5) | 1051 (31.5) | 39 (8.1) | |

| Height-for-age z-score | |||||

| < −3 | 917 (27.5) | 914 (27.4) | 917 (27.5) | 21 (60) | |

| −3 to < −2 | 925 (27.7) | 925 (27.7) | 925 (27.7) | 10 (28.6) | |

| −2 to < −1 | 815 (24.4) | 814 (24.4) | 815 (24.4) | 2 (5.7) | |

| >=−1 | 683 (20.4) | 682 (20.4) | 683 (20.4) | 2 (5.7) | |

| CD4 percentage | Missing data | 1320 | 1320 | 698 | 319 |

| median (IQR) | 14.5 (9–21.1) | 14.5 (9–21.1) | 14.2 (8.8–21) | 15 (10–21) | |

| Immunodeficiency **, n (%) | |||||

| Missing data | 1288 | 1288 | 691 | 273 | |

| Not significant | 653 (18.2) | 652 (18.2) | 478 (18) | 34 (16.4) | |

| Mild | 454 (12.7) | 454 (12.7) | 336 (12.7) | 25 (12.1) | |

| Advanced | 650 (18.1) | 649 (18.1) | 479 (18.1) | 49 (23.7) | |

| Severe | 1831 (51) | 1828 (51) | 1356 (51.2) | 99 (47.8) | |

| WHO clinical stages, n (%) | |||||

| Missing data | 785 | 782 | 598 | 113 | |

| Stage 1 | 287 (7) | 287 (7) | 126 (4.6) | 33 (9) | |

| Stage 2 | 462 (11.3) | 462 (11.3) | 267 (9.7) | 155 (42.2) | |

| Stage 3 | 2237 (54.7) | 2235 (54.7) | 1475 (53.8) | 175 (47.7) | |

| Stage 4 | 1105 (27) | 1105 (27) | 874 (31.9) | 4 (1.1) | |

| Year of ART start, n (%) | |||||

| 1999–2004 | 315 (6.5) | 315 (6.5) | 274 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

| 2005–2009 | 3269 (67) | 3265 (67) | 2328 (69.7) | 240 (50) | |

| 2010–2013 | 1292 (26.5) | 1291 (26.5) | 738 (22.1) | 240 (50) | |

| Type of regimen, n (%) | |||||

| NNRTI-based | 2762 (56.7) | 2760 (56.8) | 1945 (58.3) | 341 (71) | |

| PI-based | 2027 (41.6) | 2024 (41.6) | 1324 (39.7) | 68 (14.2) | |

| Other/unknown | 78 (1.6) | 78 (1.6) | 70 (2.1) | 71 (14.8) | |

| Outcome, n (%) *** | |||||

| Death | 217 (4.5) | 216 (4.4) | 163 (4.9) | 8 (1.7) | |

| Loss to follow-up | 241 (4.9) | 241 (4.9) | 85 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Transfer-out | 808 (16.6) | 808 (16.6) | 661 (19.8) | 0 (0) |

In the first three years after starting ART, 217 (4.5%) children died, 241 (4.9%) were lost to follow up and 808 (16.6%) were transferred to another clinic. The median follow-up between ART initiation and the last available anthropometric measurement was 11 (interquartile range 1–29; range 0–36) months. During 5,136 years of follow-up, 42,258 weight and 29,145 height measurements were recorded. A total of 3,340 children had a baseline height available and were thus included in the analysis for HAZ. The children with baseline WAZ did not substantially differ from the children with baseline HAZ.

The validation dataset consisted of 480 children with available baseline weight or height from the Kheth’Impilo cohort. All children had baseline WAZ recorded and 35 (7.3%) had baseline HAZ recorded. Children in the validation data were older, had lower baseline WAZ and HAZ, were in less severe WHO stages, were included more recently, were more likely on NNRTI-based regimens and were less often lost to follow-up or transferred out than the children in the primary dataset.

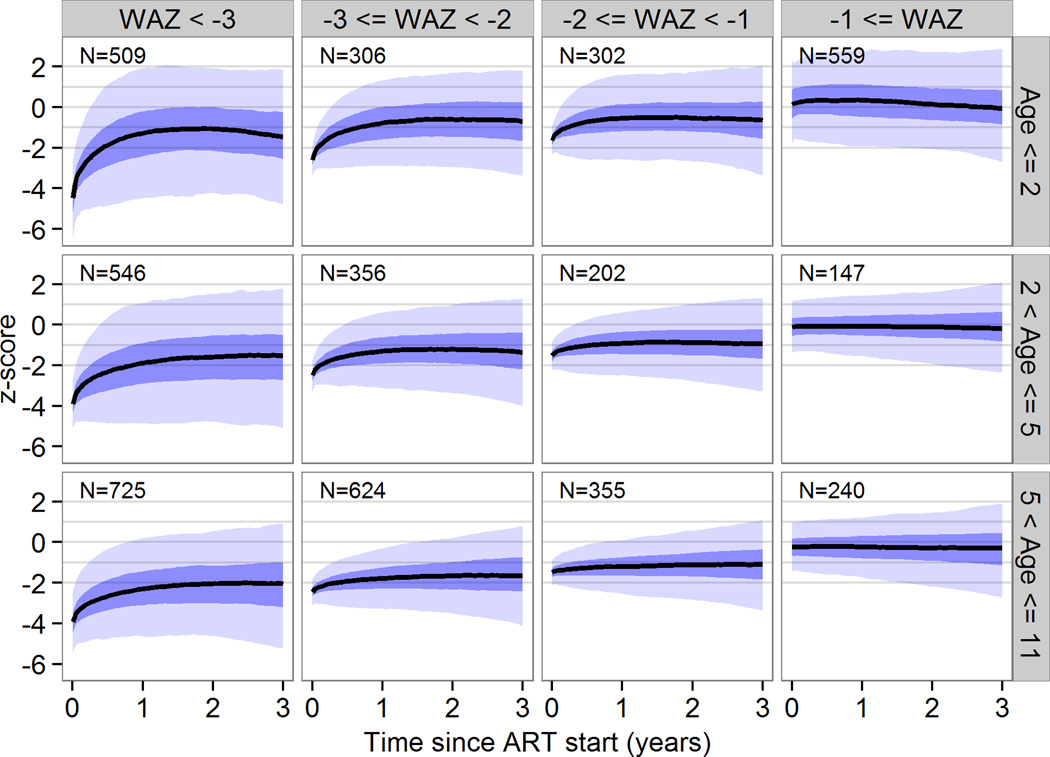

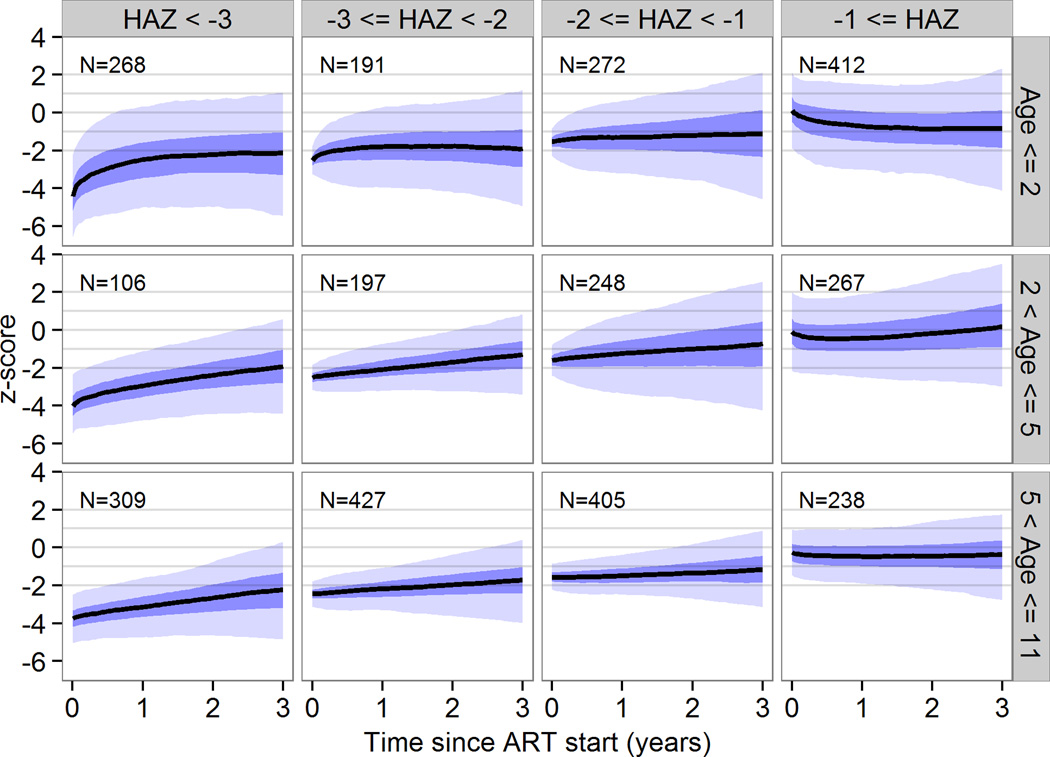

Growth trajectories for WAZ and HAZ

Baseline z-scores and age were the strongest predictors of growth response overall. Baseline viral load, CD4 and WHO stage were also associated with growth, but with a small effect estimate. For the population projections, we therefore calculated separate growth curves for children with z-scores < −3, −3 to <−2, −2 to <−1, or >−1 and age groups <2 years, 2 to <5 years and 5 to <11 years. The youngest children showed the most pronounced increase in weight and height initially but in all children catch-up growth stagnated after the first one or two years. Figure 1 shows mean WAZ with 95% prediction intervals (PrI) by baseline z-scores and age group up to 3 years after ART start. Three years after starting ART, WAZ ranged from −2.2 (95% PrI −5.6 to 0.8) in children aged 5 years or older who started with a baseline z-score of less than −3 to 0.0 (95% PrI −2.7 to 2.4) in children aged less than 2 years with a baseline WAZ greater than −1. For HAZ the corresponding range was −2.3 (95% PrI −4.9 to 0.3) in children aged 5 years or older who started with a baseline z-score of less than −3 to 0.3 (95% PrI −3.1 to 3.4) in children aged 2 to 5 years with a baseline HAZ larger than −1 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Weight for age z-scores trajectories by z-score and age at start of antiretroviral therapy in children with consistently undetectable viral load.

These curves represent population-level predictions and should not be used for individual treatment monitoring. The black lines are predicted response curves, the dark blue areas are 50% prediction intervals and the light blue areas are 95% prediction intervals. A total 4871 children from seven clinics in South Africa were included.

Figure 2.

Height for age z-scores trajectories by z-score and age at start of antiretroviral therapy in children in children with consistently undetectable viral load. These curves represent population-level predictions and should not be used for individual treatment monitoring. The black lines are predicted response curves, the dark blue areas are 50% prediction intervals and the light blue areas are 95% prediction intervals. 3340 children from 7 sites in South Africa were included.

Overall, the model fitted well in the test sample with 95% (93% during the first year) of observations included in the 95% prediction interval for WAZ. This percentage differed between subgroups. It was 89% (87% during the first year) for 0–2 year olds with baseline WAZ between −2 and −1 and 98% (97% during the first year) for 2–5 year olds with baseline WAZ less than −3.The model also fitted well for HAZ with 92% (91% during the first year) of observations in the prediction interval. This percentage was 76% (72% during the first year) for 0–2 year olds with baseline HAZ larger than −1 and 99% (97% during the first year) for 2–5 year olds with baseline HAZ between −2 and −3. In the independent validation sample, the model fitted well, with 92% (90% during the first year) of observations in the 95% prediction interval for WAZ. This percentage was 89% (87% during the first year) for 6–10 year olds with baseline WAZ larger than −1 and 96% (95% during the first year) for 2–5 year olds with baseline WAZ between −2 and −1. The validation sample only had data on HAZ for 35 patients with a total of 81% (81% during the first year) of observations in the 95% prediction interval.

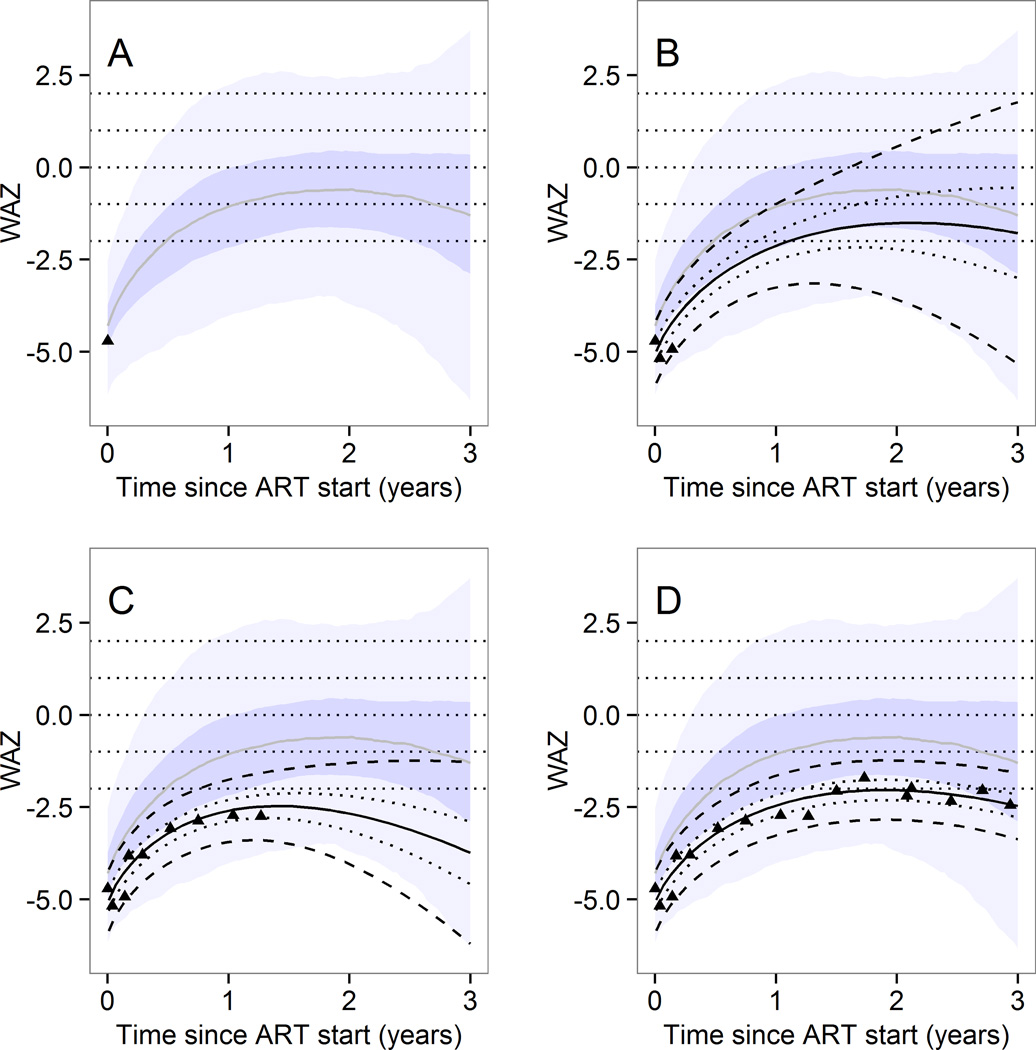

Predictions for individual children- web interface

Figure 3 shows the output of the web application, which is available online (http://growthapp.iedea-sa.org). We also provide a step-by-step manual which is available online. The web application can be used to predict WAZ and HAZ trajectories by baseline age and z-score up to 3 years after starting ART. The example shows a hypothetical child aged between 2 and 5 years whose baseline WAZ was below −3 at ART initiation. The user entered either 1, 3 (the minimally required number for individual trajectories), 9 or 16 weight measurements (shown as black triangles in panels A, B, C, and D of Figure 3). The likely evolution of WAZ is then shown for up to 3 years after ART initiation. The predictions for a particular child are adjusted each time more values are entered. The expected range of values for an HIV positive child with the same baseline age and WAZ categories and suppressed viral load values are shown as shaded areas.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the web-interface - example of individual predictions of weight for age growth trajectory.

Predictions up to 3 years after start of antiretroviral therapy can be made according to the characteristics of the child at start of antiretroviral therapy and weight measurements thereafter. Predictions are based on predictive distributions from the Bayesian multilevel model.

The example shows the actual measured values for one particular child with a baseline age of 2 to 5 years and a baseline weight for age z score

< −3. Observed values (dots) and prediction intervals (median, 50% and 95%) for that child are shown. The shaded area shows the prediction intervals for any child with the same baseline age and z-scores. The predictions for a particular child are adjusted each time more values are entered.

In panel A, only the first weight measurement was available and population-level prediction intervals are shown. In panel B, three weight measurements were available and an individual-level prediction (black) is shown on top of the population-level predictions. In panel C, 9 measurements were available and in panel D all measurements are shown. The prediction intervals for that particular child are based on the known values shown as dots.

These predictions are implemented both for weight for age and height for age and can be accessed from the following webpage: http://growthapp.iedea-sa.org. The user can introduce his own values of interest and must then specify if the predictions are for a child from a cohort which was used to develop the model or if the child comes from an external cohort.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

We provide growth reference curves up to 3 years after starting ART both at the individual and at the population level. The reference was developed in children who never had detectable viral load and growth therefore should have been closer to optimal than in children with detectable viral load. While the population-level estimations may serve as a reference for children of a certain age and z-score at start of antiretroviral therapy, the individual-level predictions take the history of previous measurements into account when making predictions. The individual-level predictions may therefore be more useful for children who deviate from the average and may be used as early warning indicators for treatment failure and comorbidities. The population-level predictions show that despite virologic suppression and initial catch-up growth, the median WAZ does not reach normal values. After about 1.5 years on ART, catch-up growth stops and in particular older children with low baseline z-scores catch-up very slowly. For HAZ the increase is less pronounced but continuous over a longer period in the older age groups.

Comparisons to other studies

The overall pattern in weight and height gain is similar to a previous study within the IeDEA collaboration where data from sites with and without viral load monitoring were combined 20. In both analyses WAZ increased rapidly in the first year of ART but stagnated thereafter, whereas HAZ increased continuously over time. However, in contrast to the previous analysis where no difference between viral load and non-viral load sites was found, we now found that WAZ in virologically suppressed children seem to be higher than in suppressed and non-suppressed combined. For example in children with a baseline WAZ of < −3, estimated WAZ at three years ranged from −1.5 to −2.2 across age groups in our analysis compared to −2.1 across all ages in the previous analysis. For HAZ no difference was found (ranging from −2 to −2.3 across age groups in our analysis compared to −2.3 previously). However, estimates between studies were not directly comparable since analyses were not stratified by age previously and loss to follow-up was lower (4.9% in our analysis versus 14.5% previously).

It remains unclear why catch-up growth in weight stops after about 1.5 years on therapy despite the continuous virologic suppression. In addition to unrecorded factors (e.g. socioeconomic status, nutrition), chronic immune-activation due to HIV or ART side effects may also play a role. A study in adults has shown that mitochondrial toxicity due to D4T may lead to weight loss in adults 21 but to our knowledge no data have been reported on children. In our study the same downwards trend in growth was apparent when children on D4T regimens were excluded from the analysis (data not shown). An analysis from rural Zambia found a similar growth pattern for both weight and height to ours. In the Zambian study mean WAZ increased rapidly from −2.4 at ART initiation to −1.3 after 6 months and decreased slightly to −1.7 after two years. During the same time mean HAZ increased almost linearly from −3.5 to −2.1. In contrast to us, other studies found a linear increase in WAZ during the first two years of ART in children older than 5 years 22 and in urban settings 23.

Comparison to HIV negative children

Unfortunately we were unable to compare our results to those from HIV negative children from the same setting. One study from Kinshasa found lower WAZ in HIV positive than HIV negative children: at 18 months WAZ was −2.3 in HIV positive compared to −1.3 in HIV negative children – irrespective if the mother was HIV positive or not. For HAZ the difference persisted but was only about half a z-score lower in HIV positive vs negative children 24. Similarly in an Ugandan trial HIV infected children weighed less and were shorter during the whole 5 years of follow-up after birth 25. In these studies children were followed from birth and no distinction was made between those with and without virologic suppression.

Predictors of growth response

Many factors may influence growth and simply having a continually suppressed viral load does not imply that normal growth will be achieved. Growth response has been shown to be better in younger children 26,27, and in children with low CD4 cell percentages and advanced stage of disease 28,29. Other individual- and site-level factors associated with poor growth, but not recorded in our database, include co-infections (such as Tuberculosis) and other comorbidities, low socioeconomic status and poor nutrition or food insecurity or the lack of food supplementation programs 30,31.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the analysis are that children from many sites and settings were included and that the characteristics of the children at start of ART are typical for the region. We used state of the art statistical analysis techniques and validated the prediction in an independent sample. Although viral load and non-viral load sites may differ with regard to many factors, our results may serve as a reference in sites where viral load monitoring is not available.

The study also has a number of limitations. Since the analysis was restricted to sites where viral load monitoring is available in order to assess virologic suppression, all included sites were in South Africa where the standard of care is higher than in other sites and the results may not necessarily be generalizable to other settings. Our selection criteria also restricted the available sample size and the follow-up duration; in particular the number of children with height measurements was limited. Due to this limited sample size and since weight and height measurements were not always available at the same time point, an analysis of WHZ was not possible. Also children must have had at least 3 anthropometric measurements to make individual-level predictions of growth response. There was considerable loss to follow-up, which limited the precision of the population estimates during the third year. Although we included only virologically suppressed children, which indicates good adherence, adherence was not explicitly recorded and intermittent poor adherence including unmeasured viral failures are possible. Our results represent trajectories of children who remained in care. Children who were lost to follow-up, who transferred-out or who died may have different growth responses. If sicker patients are more likely to get lost, our analysis overestimates growth response. We were unable to compare PI based regimen and NNRTI based regimen, because the distribution of regimens were unbalanced across age groups. Finally, the model cannot predict the probability of viral failure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to all children, care givers and data managers involved in the participating sites.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [5U01-AI069924–05] and the Swiss National Science Foundation [Prosper grant 32333B_131629 to O.K. and ProDoc PhD grant PDFMP3_137106 to N.B. and O.K.]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

SDC figure: Flowchart of included and excluded children

References

- 1.Benjamin DK, Jr, Miller WC, Ryder RW, Weber DJ, Walter E, McKinney RE., Jr Growth patterns reflect response to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive infants: potential utility in resource-poor settings. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18(1):35–43. doi: 10.1089/108729104322740901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weigel R, Phiri S, Chiputula F, et al. Growth response to antiretroviral treatment in HIV-infected children: a cohort study from Lilongwe, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(8):934–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yotebieng M, Van Rie A, Moultrie H, Meyers T. Six-month gain in weight, height, and CD4 predict subsequent antiretroviral treatment responses in HIV-infected South African children. AIDS. 2010;24(1):139–146. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328332d5ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chantry CJ, Cervia JS, Hughes MD, et al. Predictors of growth and body composition in HIV-infected children beginning or changing antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2010;11(9):573–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillen S, Ramos JT, Resino R, Bellon JM, Munoz MA. Impact on weight and height with the use of HAART in HIV-infected children. Pediatr Infect J. 2007;26(4):334–338. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000257427.19764.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weigel R, Phiri S, Chiputula F, et al. Growth response to antiretroviral treatment in HIV-infected children: a cohort study from Lilongwe, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(8):934–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kekitiinwa A, Lee KJ, Walker AS, et al. Differences in factors associated with initial growth, CD4, and viral load responses to ART in HIV-infected children in Kampala, Uganda, and the United Kingdom/Ireland. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(4):384–392. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818cdef5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nachman SA, Lindsey JC, Moye J, et al. Growth of human immunodeficiency virus-infected children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect J. 2005;24(4):352–357. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000157095.75081.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fatti G, Bock P, Eley B, Mothibi E, Grimwood A. Temporal trends in baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes of children starting antiretroviral treatment: an analysis in four provinces in South Africa, 2004–2009. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2011;58(3):e60–e67. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182303c7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leroy V, Malateste K, Rabie H, et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral therapy in children in Asia and Africa: a comparative analysis of the IeDEA pediatric multiregional collaboration. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2013;62(2):208–219. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827b70bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egger M, Ekouevi DK, Williams C, et al. Cohort Profile: the international epidemiological databases to evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(5):1256–1264. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Group WMGRS. WHO Child Growth Standards. 2006 Available at: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.

- 14.WHO Case Definitions of HIV for Surveillance and Revised Clinical Staging and Immunological Classification of HIV-Related Disease in Adults and Children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royston P, Altman DG. Regression Using Fractional Polynomials of Continuous Covariates: Parsimonious Parametric Modelling. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 1994;43(3):429–467. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Congdon P. Applied Bayesian Hierarchical Methods. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N, Spiegelhalter D. WinBUGS -- a Bayesian Modelling Framework: Concepts, Structure, and Extensibility. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gsponer T, Weigel R, Davies MA, et al. Variability of growth in children starting antiretroviral treatment in southern Africa. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):e966–e977. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Griensven J, De Naeyer L, Mushi T, et al. High prevalence of lipoatrophy among patients on stavudine-containing first-line antiretroviral therapy regimens in Rwanda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(8):793–798. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolton-Moore C, Mubiana-Mbewe M, Cantrell RA, et al. Clinical outcomes and CD4 cell response in children receiving antiretroviral therapy at primary health care facilities in Zambia. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298(16):1888–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutcliffe CG, van Dijk JH, Bolton-Moore C, Cotham M, Tambatamba B, Moss WJ. Differences in presentation, treatment initiation, and response among children infected with human immunodeficiency virus in urban and rural Zambia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(9):849–854. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e753a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey RC, Kamenga MC, Nsuami MJ, Nieburg P, St Louis ME. Growth of children according to maternal and child HIV, immunological and disease characteristics: a prospective cohort study in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(3):532–540. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owor M, Mwatha A, Donnell D, et al. Long-term follow-up of children in the HIVNET 012 perinatal HIV prevention trial: five-year growth and survival. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2013;64(5):464–471. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gsponer T, Weigel R, Davies MA, et al. Variability of growth in children starting antiretroviral treatment in southern Africa. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):e966–e977. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nachman SA, Lindsey JC, Moye J, et al. Growth of human immunodeficiency virus-infected children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect J. 2005;24(4):352–357. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000157095.75081.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guillen S, Ramos JT, Resino R, Bellon JM, Munoz MA. Impact on weight and height with the use of HAART in HIV-infected children. Pediatr Infect J. 2007;26(4):334–338. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000257427.19764.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGrath CJ, Chung MH, Richardson BA, Benki-Nugent S, Warui D, John-Stewart GC. Younger age at HAART initiation is associated with more rapid growth reconstitution. AIDS. 2011;25(3):345–355. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834171db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arpadi SM. Growth failure in children with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(Suppl 1):S37–S42. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller TL. Nutritional aspects of HIV-infected children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003;17(Suppl 1):S130–S140. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]