Abstract

Background

Unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) portends a poor prognosis despite standard systemic treatments which confer minimal survival benefits and significant adverse effects. This study aimed to assess clinical outcomes, complications and prognostic factors of TAE therapies using chemotherapeutic agents or radiation.

Methods

A literature search and article acquisition was conducted on PubMed (MEDLINE), OVID (MEDLINE) and EBSCOhost (EMBASE). Original articles published after January 2000 on trans-arterial therapies for unresectable ICC were selected using strict eligibility criteria. Radiological response, overall survival, progression-free survival, safety profile, and prognostic factors for overall survival were assessed. Quality appraisal and data tabulation were performed using pre-determined forms. Results were synthesized by narrative review and quantitative analysis.

Results

Twenty articles were included (n=929 patients). Thirty three percent of patients presented with extrahepatic metastases. After treatment, the average rate of complete and partial radiological response was 10% and 22.2%, respectively. Overall median survival time was 12.4 months with a median 30-day mortality and 1-year survival rate of 0.6% and 53%, respectively. Acute treatment toxicity (within 30 days) was reported in 34.9% of patients, of which 64.3% were mild to moderate in severity. The most common clinical toxicities were abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and fatigue. Multiplicity, localization and vascularity of the tumor may predict worse overall survival.

Conclusions

Trans-arterial therapies are safe and effective treatment options which should be considered routinely for unresectable ICC. Consistent and standardized methodology and data collection is required to facilitate a meta-analysis. Randomized controlled trials will be valuable in the future.

Keywords: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), unresectable, embolization, survival

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is a devastating malignancy of the biliary tree which is notoriously difficult to diagnose (1). Survival remains at less than 12 months after diagnosis due to clinical latency, lack of effective non-surgical therapies and aggressive tumors (1-4). Surgical resection is the only chance of cure, but in up to 70% of cases ICC is unresectable (5-8). Systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy as primary, adjuvant or palliative treatments have poor response rates and are limited by systemic toxicities (9-14).

Since 1980, TAE has become available for targeted treatment of both primary and secondary hepatic malignancies (15). The common modalities for TAE are bland embolization, trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) or chemoinfusion (TACI), and selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT). These are performed via the hepatic artery and allow selective delivery of anti-tumor agents or radioactive microspheres. This targeted approach minimizes systemic toxicity or exposure of healthy tissue to radiation.

TACE and TACI have shown to improve median survival by 2-7 months compared to systemic therapies (16). Several observational studies on SIRT have also reported similar benefits on overall survival and tumor response rates of up to 86% (17-19). In the context of inoperability and increasing evidence of survival benefit conferred by trans-arterial approach, such therapies have become important and widely used treatment options. However, systematic evaluation of data for each treatment modality remains limited.

This study reviews the effect of trans-arterial emoblisation therapies for unresectable ICC. Primary outcomes were response and survival outcomes. Secondary outcomes were treatment complications and prognostic factors for overall survival.

Methods

The structure of this systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines (20).

Definition of treatment modalities

TACE delivers high doses of chemotherapy directly to the cancer cells via the hepatic artery. Additionally, embolic agents are injected to reduce arterial inflow and increase bioavailability of the drugs (21). Bland embolization is another form of TACE that uses particles and/or embolic agents to block blood flow to the tumor without the use of chemotherapeutic agents. Another alternative includes the use of drug-eluting beads embedded with irinotecan (DEBTACE).

TACI is a catheter-based therapy using an arterial port in the hepatic artery. Its delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs is similar to TACE, but embolization is not used in TACE. TACI maximizes targeted drug delivery by selective vessel catheterization (5).

SIRT delivers internal radiation selectively to the tumor bed. Yttrium-90 (Y90) is impregnated in glass or resin-based microspheres (5). The type, size and number of microspheres per treatment varies (22).

Eligibility criteria

Studies considered for review had the following pre-determined inclusion criteria: (I) adult patients with primary ICC; (II) unresectable, chemorefractory or failed previous surgical resection; (III) TAE as the treatment modality; and (IV) clinical outcomes and complications assessed and reported. Resectibility is assessed using patient and disease factors including comorbidities, fitness for surgery and tumor location and size (23). A tumor is deemed unresectable if clear margins cannot be achieved by resection and there are evidence of metastases (24,25).

These studies were restricted according to the following report characteristics: (I) publication date after January 2000; (II) English language; and (III) original research. The search period was restricted to be more representative of modern post-operative outcomes.

Information sources and search strategy

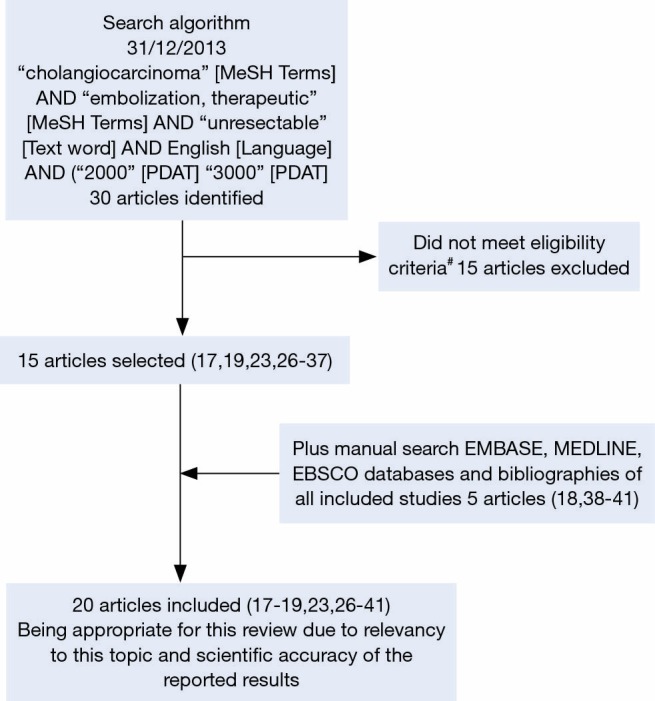

On December 2013, a literature search was conducted using MeSH keyword search on PubMed (MEDLINE) for all studies which matched the eligibility criteria above (Figure 1). An additional manual search of OVID (MEDLINE) and EBSCOhost (EMBASE) as well as bibliographies of each included study was conducted to identify studies not covered by the initial MeSH keyword search. All identified articles were retrieved from the aforementioned databases.

Figure 1.

Search algorithm (17-19,23,26-41). #, eligibility criteria outlined in methods section: (I) adult patients with primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; (II) unresectable, chemorefractory or failed previous surgical resection; (III) patients received transarterial chemoembolization, chemoinfusion, and/or radioembolization; (IV) assessment of clinical outcomes and complications; (V) original research.

Study selection

Following the search, two reviewers independently performed screening of titles and abstracts after MeSH keyword and manual searches. Studies were excluded if they did not meet eligibility criteria. Consensus for studies included for review was achieved by discussion between reviewers based on the pre-determined eligibility criteria.

Studies were classified into levels of evidence using the National Health and Medical Research Council evidence hierarchy (42).

Data items and extraction

All data items for assessment of study quality (Table 1) and study results (Table 2) were pre-determined. Data extraction was then performed by two independent reviewers using a standardised protocol. Data extracted include the methodology, quality appraisal, patient characteristics, treatment toxicity, radiological response, overall survival, progression-free survival and prognostic factors. Overall survival and progression-free survival were determined from the time of TAE.

Table 1. Quality appraisal.

| Author, year | Study design | Patients | Treatment | Follow-up duration (months) | Explicit inclusion criteria | Previous treatments (%) |

Concomitant CTx | Comparison groups | Level of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTx | Resection | |||||||||

| Burger (23), 2005 | P | 17 | TACE | 16 | Yes | 35 | 0 | No | None | II |

| Herber (37), 2007 | R | 15 | TACE | 3 | Yes | 4 | 1 | No | None | III |

| Aliberti (34), 2008 | P | 11 | TACE + DEBTACE | NR | Yes | NR | NR | No | CTx | II |

| Gusani (35), 2008 | R | 42 | TACE | NR | Yes | NR | NR | No | TACE combinations: gemcitabine only; gemcitabine followed by cisplatin; gemcitabine followed by oxaliplatin; gemcitabine + cisplatine; gemcitabine + cisplatin followed by oxaliplatin | III |

| aIbrahim (18), 2008 | P | 24 | Glass microspheres | 17.7 | Yes | 29 | NR | No | None | II |

| Kim (36), 2008 | R | 49 | TACE, TACI | 8 | Yes | NR | NR | No (adjuvant radiation 33%) | TACE; TACI; TACE + TACI | III |

| Shitara (41), 2008 | R | 20 | TACI | NR | Yes | 0 | 0 | No | None | III |

| Poggi (33), 2009 | R | 9 | Oxaliplatin eluting microspheres-TACE | 20 | Yes | 0 | 0 | Yes | CTx | III |

| aSaxena (17), 2010 | P | 25 | SIRT | 8.1 | Yes | 18 | 10 | Yes (28%) | No | II |

| aHaug (27), 2011 | P | 26 | SIRT | NR | Yes | 17 | 8 | No | None | II |

| Kiefer (31), 2011 | P | 62 | TACE | NR | Yes | 18 | 7 | No | None | II |

| Park (32), 2011 | R | 72 | TACE | NR | Yes | NR | NR | No | Supportive treatment | III |

| aSchiffman (40), 2011 | P | 24 | DEBTACE | 13.6 | Yes | 80 | 29 | No | None | II |

| Hoffman (19), 2012 | R | 33 | SIRT | 13.5 | Yes | 27 | 12 | No | None | III |

| Kuhlmann (29), 2012 | R | 26 | TACE + DEBTACE | 12 | Yes | 5 | 1 | No | TACE + DEBTACE; TACE; ChT | III |

| 10 | TACE | 1.8 | Yes | 2 | 0 | No | ||||

| 31 | ChT (gemcitabine & oxaliplatin) | 13 | Yes | 0 | 7 | No | ||||

| Vogl (30), 2012 | R | 115 | TACE | NR | Yes | NR | NR | No | All TACE: mitomycin-C; gemcitabine; mitomycin-C + gemcitabine; mitomycin-C + gemcitabine +cisplatin | III |

| aHyder (38), 2013 | R | 198 | SIRT | NR | No | 55 | 23 | 30 patients (15%) | All IAT: TACE; | III |

| DEBTACE; bland embolization; Yttrium-90 | ||||||||||

| aMouli (26), 2013 | R | 46 | SIRT | 29 | Yes | 16 | 5 | No | None | III |

| aRafi (39), 2013 | P | 19 | SIRT | 15 | Yes | 19 | NA | No | None | II |

| Scheuermann (28), 2013 | R | 32 | Lipiodol and mitomycin C, doxorubicin | 10 | Yes | NA | NA | Adjuvant CTx | Resection; CTx/supportive | III |

| Median | 13.5 | 35 | 11.6 | |||||||

| Range | 1.8-29 | 27-100 | 10-40 | |||||||

a, SIRT. CTx, systemic chemotherapy; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; DEBTACE, drug eluting beads TACE; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; P, prospective; R, retrospective; TACI, trans-arterial chemoinfusion; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy.

Table 2. Summary of patient characteristics.

| Author, year | Demographics | TACE |

Yttrium therapy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regime | No. procedures | Median tumor size (cm) | Single session (%) | Whole hepatic therapy (%) | Mean activity | ||

| Burger (23), 2005 | Male: 24%; age: 56; bilobar disease: 24%; extrahepatic metastasis: 12% | Variable | 2 | NR | NA | NA | NA |

| Herber (27), 2007 | Male: 33%; age: 63.6; bilobar disease: 60%; extrahepatic metastasis: 0% | Lipiodol (10mL) and mitomycin (10 mL) | 3.9 | 10.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| Aliberti (34), 2008 | Male: NR; age: 68.5; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: NR | DC beads loaded with doxorubicin | 3 | 6.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Gusani (35), 2008 | Male: 50%; age: 58.8; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: NR | Gemcitabine, gemcitabine then cisplatin, gemcitabine then oxaliplatin, gemcitabine + cisplatin, gemcitabine + cisplatin then oxaliplatin | 3 | NR | NA | NA | NA |

| aIbrahim (18), 2008 | Male: 67%; age: 68; bilobar disease: 67%; extrahepatic metastasis: 33% | NA | NA | NA | 38 | 42 | NR |

| Kim (36), 2008 | Male: 76%; age: 62.9; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: 51% | Lipiodol and cisplatin | 3 | 8.9 | NA | NA | NA |

| Shitara (41), 2008 | Male: 59%; age: 74.5; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: 85% | Mitomycin C | 8 | 7.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| Poggi (33), 2009 | Male: 65%; age: 66.5; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: NR | Oxaliplatin then CTx | TACE (1-7 cycles); CTx (3-7 cycles) | NR | NA | NA | NA |

| aSaxena (17), 2010 | Male: 52%; age: 57; bilobar disease: 80%; extrahepatic metastasis: 49% | NA | NA | NA | All | 80 | 1.76 |

| aHaug (27), 2011 | Male: 58%; age: 64.3; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: 31% | NA | NA | NA | All | 85 | 1.74 |

| Kiefer (31), 2011 | Male: 40%; age: 62; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: 31% | Cisplatin, doxorubicin, mitomycin C, ethiodol, polyvinyl alcohol | 2 | NR | NA | NA | NA |

| Park (32), 2011 | Male: 65%; age: 63.9/65.3; bilobar disease: 51%; extrahepatic metastasis: 54% | NR | 2.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| aSchiffman (40), 2011 | Male: 38%; age: 68; bilobar disease: 33%; extrahepatic metastasis: 40% | Irinotecan or doxorubicin | 1 session, 50%; median, NR | 11.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Hoffman (19), 2012 | Male: 18%; age: 65; bilobar disease: 63%; extrahepatic metastasis: 24% | NA | NA | NA | All | 64 | 1.54 |

| Kuhlmann (29), 2012 | Male: 58%; age: 67; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: 42% | Total, 14; median, NR | NR | NA | NA | NA | |

| Male: 80% | Total, 14; median, NR | NR | NA | NA | NA | ||

| age: 62 | |||||||

| bilobar disease: NR | |||||||

| extrahepatic metastasis: 40% | |||||||

| Male: 42%; age: 63; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: 90% | NR | NR | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Vogl (30), 2012 | Male: 52%; age: 60.4; bilobar disease: 77%; extrahepatic metastasis: NR | Mitomycin C only, gemcitabine, mitomycin C + gemcitabine, mitomycin C + gemcitabine + cisplatin | NR | NR | NA | NA | NA |

| aHyder (38), 2013 | Male: 48%; age: NR; bilobar disease: NR; extrahepatic metastasis: 9.6% | Gemcitabine + cisplatin, cisplatin + doxorubicin + mitomycin, gemcitabine alone, cisplatin alone | 2 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| aMouli (26), 2013 | Male: 54%; age: 68; bilobar disease: 36%; extrahepatic metastasis: 35% | NA | NA | NA | 30 | 30 | NR |

| aRafi (39), 2013 | Male: 37%; age: 61; bilobar disease: 42%; extrahepatic metastasis: 58% | NA | NA | NA | 79 | NR | 1.2 |

| Scheuerman (28), 2013 | Male: 53%; age: 64; bilobar disease: 59%; extrahepatic metastasis: NR | Lipiodol + mitomycin C, doxorubicin | 3 | NR | NA | NA | NA |

| Median | Male: 52%; age: 63.3; bilobar disease: 59.5%; extrahepatic metastasis: 35% | 9.2 | |||||

| Range | Male: 18-76%; age: 57-74.5; bilobar disease: 24-80; extrahepatic metastasis: 9.6-85 | 6.5-11.5 | |||||

a, SIRT. CTx, systemic chemotherapy; DEBTACE, drug eluting beads TACE; N, not applicable; NR, not reported; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; TACI, trans-arterial chemoinfusion; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy.

Synthesis of results

Data was synthesized by qualitative and quantitative review based on the outcomes criteria and data extracted in tables as outlined above. Statistical data are presented as percentages or median (range). A meta-analysis was not performed due to the following reasons: (I) heterogeneous data prevented complete meta-analysis; some studies had no reference population and others compared trans-arterial therapy with surgery or systemic chemotherapy; (II) statistical limitations due to missing data or inconsistencies in data presentation and (III) methodological inconsistencies such as varied follow-up time points for survival rates.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias in individual studies was assessed by a qualitative analysis based on study quality and data tabulated in Table 1.

Results

Study selection

After careful systematic selection, 20 studies were selected for review (17-19,23,26-41). Full details of the search algorithm are outlined in Figure 1.

Study characteristics and risk of bias within studies (Table 1)

The sample size ranged between 9 to 198. Only four studies included greater than 50 patients (30-32,38). The number of patients in most studies is low and this is a significant source of bias.

Seven studies used radioembolization (17-19,26,27,38,39). Hyder et al. compared TACE, DEBTACE and traditional SIRT (38). TACI was assessed in two studies (36,41). One study compared TACE with systemic chemotherapy (29) and nine studies assessed TACE with no comparators (23,28,30-33,35,37,40).

Heterogeneous patient demographics, tumor type and pathology, and treatment combinations in included studies resulted in a wide range of results derived from each article (Tables 1,2). This discrepancy reflects the lack of standardized protocol for trans-arterial therapies to facilitate consistent patient selection and treatment regimens. These therapies are relatively new, and although their efficacy has been reported in multiple studies, a summary of evidence is required.

Study design limited the strength of evidence of included articles. Twelve studies were retrospective (19,26,28-30,32,33,35-38,41) and no randomized controlled trial was present in this review. Both are potential sources of bias. The reasons for the lack of randomized studies may be multifactorial. In the context of known survival benefit conferred by trans-arterial therapies, it may be unethical to deny patients trans-arterial therapies.

All studies had level of evidence II and III. The results of studies were similar between lower (19,26,28-30,32,33,35-38,41) and higher level (17,18,23,27,31,34,39,40) evidence articles which demonstrates good consistency of results across studies.

Patient characteristics (Table 2)

The median age at the time of each study was between 56 and 68. The mean follow-up period was 13.7 (1.9-29) months.

The majority of patients had bilobar disease 59.5% (24-77%). Extra-hepatic metastases were present in 35% (12-85%) of patients with 35% (27-100%) of patients having received previous chemotherapy. Prior liver resection was undertaken in 11.6% (11-40%) of patients. Post-procedure chemotherapy was administered in eight studies (17,28,33,35,36,38,40,41).

Assessment of outcomes (Table 3)

Table 3. Results of included studies.

| Author, year | Treatment | Response (RECIST) % |

Progression-free survival (months) | Overall survival |

Key points | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | PR | SD | PD | Median (months) | 6 months (%) | 1 year (%) | 2 years (%) | 3 years (%) | 5 years (%) | |||||

| Burger (23), 2005 | TACE | 75% tumor necrosis on magnet resonance imaging in 44%. PR not achieved | NR | 23 | 95 | 78 | 30 | NR | NR | Well-tolerated by 82% | ||||

| Herber (37), 2007 | TACE | 0 | 7 | 70 | 27 | NR | 21 | NR | 51 | 27.5 | 27.5 | NR | TACE is a safe procedure with a moderate number of complications for inoperable CCA | |

| Aliberti (34), 2008 | TACE + DEBTACE | 10 | 90 | 0 | 0 | NR | 13 | 100 | 76 | NR | NR | NR | A response rate of 100% on RECIST. Well tolerated by all patients | |

| Gusani (35), 2008 | TACE | 0 | 0 | 57 | 43 | NR | 9.1 | 65 | 38 | 14 | 4 | 0 | Median survival with gemcitabine-cisplatin combination TACE had significantly longer survival (13.8 months) compared gemcitabine alone (6.3 months) | |

| aIbrahim (18), 2008 | SIRT | 9 (EASL) | 27 (EASL) | 68 (EASL) | NR | NR | 14.9 | NR | Baseline ECOG is a prognostic factor for survival. The median survival for patients with an ECOG performance status of 0, 1, and 2 was 31.8 months, 6.1 months, and 1 month, respectively | |||||

| Kim (36), 2008 | TACI, TACE | 35 | 20 | NR | NR | 10 | 12 | NR | 46 | 38 | 30 | NR | 55% clinical success | |

| Shitara (41), 2008 | TACI | 5 | 45 | 0 | 10 | 8.3 | 14.1 | NR | The response rate was 50.0%. Median survival was 14.1 months | |||||

| Poggi (33), 2009 | Oxaliplatin eluting microspheres-TACE | 0 | 44 | 56 | 0 | 8.4 | 30 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Significantly increased overall survival with no major adverse events. Decrease in tumor size | |

| aSaxena (17), 2010 | SIRT | 0 | 26 | 48 | 22 | NR | 9.3 | 56 | 40 | 27 | 13 | NR | Two factors were associated with an improved survival: peripheral tumor type and ECOG status of 0. | |

| aHaug (27), 2011 | SIRT | NR | 22 | 65 | 13 | NR | 12.5 | 79 | 53 | 31 | NR | NR | FDG PET/CT was able to predict patient outcome after radioembolization treatment, with the change in metabolically active tumour volume at 3 months being the best independent predictor. High tumour vascularization was not a prerequisite for successful radioembolisation | |

| Kiefer (31), 2011 | TACE | 0 | 7 | 60 | 27 | NR | 21.1 | NR | 51 | 27.5 | 27.5 | NR | Median survival from time of first chemoembolization was 15 months | |

| Park (32), 2011 | TACE | 0 | 23 | 67 | 11 | NR | 12.2 | 76 | 51 | 12 | 10 | 5 | Survival period was longer in the TACE group (median 12.2 months) than in the symptomatic treatment (median 3.3 months) group | |

| aSchiffman (40), 2011 | DEBTACE | 6 | 6 | 72 | 17 | NR | 17.5 | NR | DEBTACE is safe and effective, providing a marked survival benefit when DEB therapy is used as adjunctive therapy to systemic CTx | |||||

| Hoffman (19), 2012 | SIRT | 0 | 36 | 52 | 15 | 9.8 | 22 | 83 | 61 | 41 | 12 | 0 | Predictors for prolonged survival are performance status, tumor burden and RECIST response | |

| Kuhlmann (29), 2012 | NR | 4 | 42 | 50 | 3.9 | 11.7 | NR | This is the first study demonstrating that DEBTACE-TACE is safe in patients with normal liver function, and results in a prolongation of PFS and OS. Local tumor control, PFS and OS similar to systemic ChT with oxaliplatin and gemcitabine, but superior to cTACE | ||||||

| NR | 10 | 10 | 60 | 1.8 | 5.7 | |||||||||

| NR | 26 | 45 | 29 | 6.2 | 11 | |||||||||

| Vogl (30), 2012 | TACE | 0 | 9 | 57 | 34 | NR | 13 | NR | 52 | 29 | 10 | 8 | No statistically significant difference between patients treated with different chemotherapy protocols was noted | |

| aHyder (38), 2013 | Total | 3.1 | NR | 61.5 | 13 | NR | 13.2 | NR | 54 | NR | 22 | 16 | Similar results across different types of trans-arterial therapy | |

| 34.6 (EASL) | 47.5 (EASL) | |||||||||||||

| SIRT | NR | 11.6 | NR | |||||||||||

| TACE | 13.4 | |||||||||||||

| aMouli (26), 2013 | SIRT | 0 | 2.5 (WHO), 9 (EASL) | 73 (WHO), 64 (EASL) | 2 (WHO), 0 (EASL) | NR | Overall: 14.6 | NR | Solitary tumor is a prognostic factor with tumor reduction allowing conversion to surgical resection for curative therapy | |||||

| Multifocal: 5.7 | ||||||||||||||

| Infiltrative: 6.1 | ||||||||||||||

| Bilobar: 10.9 | ||||||||||||||

| aRafi (39), 2013 | 0 | 11 | 68 | 21 | NR | 11.5 | 67 | 56 | 10 | 0 | 0 | No deaths within 30 days | ||

| Scheuerman (28), 2013 | TACE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11 | 64 | 42 | 26 | 15 | 8 | There is no significant survival benefit of surgery in lymph node positive patients or positive resection margin over TACE | |

| Median | All | 6 | 22.4 | 60 | 19.5 | 8.15 | 13 | 53.5 | ||||||

| TACE/TACI | 10 | 20 | 57 | 15 | 8 | 13 | 53 | |||||||

| SIRT | 0 | 25.5 | 66.5 | 15 | 9.8 | 12.5 | 54.5 | |||||||

| Range | All | 3.1-35 | 6-44 | 10-72 | 5-43 | 1.8-9.8 | 5.7-30 | 38-78 | ||||||

a, SIRT. CR, complete response; CTx, systemic chemotherapy; DEBTACE, drug eluting beads TACE; EASL, European Association for the Study of Liver Tumor Response Criteria; NR, not reported; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; TACI, trans-arterial chemoinfusion; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy; SR, stable response; WHO, World Health Organization Tumor Response Criteria.

Follow-up occurred for 13.3 [8-29] months after therapy and radiological tumor response was recorded using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) in all studies. The average reported RECIST value for complete and partial response (PR) was 6% (0-35%) and 22.4% (7-90%), respectively. The time to tumor progression was 8.2 (1.8-10) months with a median overall survival of 13 (9.1-30) months amongst all treatment modalities. Median overall survival in studies using radioembolization was 12.5 months and in studies using chemoembolization was 13 months. Overall 1-year survival for all treatments was 53.5 [40-78] months [median: SIRT 54.5% (40-61%), TACE 53% (38-78%)].

Treatment toxicity (Table 4)

Table 4. Summary of toxicity after trans-arterial therapies.

| Author, year | Treatment | Acuity (days) | Toxicity (%) |

Severity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Fatigue | Abdominal pain | Nausea/vomiting | Haematological | GIT ulcers | Deranged LFTs | Other | Grade 1-2 | Grade 3-4 | |||

| Burger (23), 2005 | TACE | <30 | 17 | NR | 6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6 |

| Herber (37), 2007 | TACE | <30 | 40 | NR | 40 | 27 | NR | 7 | Hepatic arteries spasm 13; anaphylactic shock 7 | NR | NR | |

| Aliberti (34), 2008 | TACE + DEBTACE | <30 | NR | 0 | 100 | 95 | 0 | 0 | Neoplastic fever 100; hepatic abscess 3 | NR | NR | |

| Gusani (35), 2008 | TACE | <30 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Thrombocytopenia 5 | NR | Bilirubin 5 | AMI 2; hepatic abscess 2 | 38 | 17 |

| aIbrahim (18), 2008 | SIRT | NR | NR | 75 | 38 | 17 | NR | 4 | Bilirubin (grade 3) 4; albumin (grade 3) 71 | NR | NR | 4 |

| Kim (36), 2008 | OEM-TACE | 10 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Most had post-embolization syndrome which resolved | NR | NR |

| Shitara (41), 2008 | TACI | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Neutropenia 4 | 20; perforated 5 | Gastritis 6, cholangitis 6 | NR | 6 | |

| Poggi (33), 2009 | Oxaliplatin eluting microspheres-TACE | <30 | NR | 0 | 42 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | Peripheral neuropathy 4; cholangitis 1.5; hypertensive crisis 1.5 | NR | NR |

| aSaxena (17), 2010 | SIRT | <30 | NR | 64 | 40 | Nausea 16, vomiting 8 | 0 | 4 | Albumin 8, bilirubin 4 | Alkaline toxicity 4; anorexia 16; ascites 16; pleural effusion 8; pulmonary embolism 4 | NR | 4 |

| aHaug (27), 2011 | SIRT | 2 | NR | NR | 58 | Nausea 50; vomiting 19 | 0 | 8 | 0 | NR | NR | 0 |

| Kiefer (31), 2011 | TACE | 1 | 65 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Post-embolization syndrome 65 | 65 | 3% APE |

| Park (32), 2011 | TACE | <30 | NR | NR | 4 | 1 | 13 | 13 | AST 2.3; ALT 1.1; ALP 2.3; bilirubin 11.2; hypoalbuminemia 5.7 | NR | NR | 37 |

| aSchiffman (40), 2011 | TACE | 1-3 | 26.2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Hepatorenal syndrome 4 | Post-embolization syndrome 27; pneumonia 4; atrial fibrillation 8 | 63.6 | 36.3 |

| Hoffman (19), 2012 | SIRT | NR | NR | NR | 85 | Nausea 61; vomiting 27 | 0 | 0 | Bilirubin 70; AST 55; ALT 33 | NR | NR | 0 |

| Kuhlmann (29), 2012 | TACE + DEBTACE | NR | NR | NR | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | Hepatic abscess 4; pleural empyema 4 | NR | NR |

| TACE | NR | NR | 10 | 50 | 30 | 0 | 0 | Liver failure 10 | Hypertension 20; urticaria 10; pulmonary embolism 10; cholangitis 10 | NR | NR | |

| CTx | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Febrile neutropenia 6 | NR | NR | Death 10; peripheral neuropathy 19 | NR | NR | |

| Vogl (30), 2012 | TACE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| aHyder (38), 2013 | Various | NR | 29.8 | 17 | 12.1 | 6.1 | 0 | 0 | Jaundice 2; hepatorenal syndrome 8 | NR | NR | 16 |

| aMouli (26), 2013 | SIRT | NR | NR | 54 | 28 | Nausea 13; vomiting 9 | NR | 2 | Albumin (grade 3) 9; bilirubin (grade 3) 7 | Ascites 15; pleural effusion 4 | NR | NR |

| aRafi (39), 2013 | SIRT | NR | 89 | 21 | 32 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 32 | 21 | 79 | 11 |

| Scheuerman (28), 2013 | TACE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Liver failure 2 | Septic shock 2; multiple organ failure 4; AMI 11 | NR | NR |

| Median | 34.9 | 19 | 40 | 27 | 4 | 3 | Liver failure 4 | - | 64.3 | 8.5 | ||

| Range | 26.2-89 | 0-75 | 4-100 | 6.1-95 | 0-13 | 0-20 | 2-10 | - | 38-79 | 0-37 | ||

a, SIRT. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; APE, acute pulmonary edema; CTx, systemic chemotherapy; DEBTACE, drug eluting beads TACE; LFT, liver function test; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; TACI, trans-arterial chemoinfusion; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy.

Table 4 summarizes adverse effects associated with trans-arterial therapies. Side effects related to post-embolization syndrome in several studies occurred within the first few days of treatment (27,31,36,40). Other complications were reported within 30 days of treatment. Delayed toxicity was not reported. The overall rate of acute toxicity was 34.9% (26.2-89%). Twelve studies graded the severity of toxicities (17-19,23,27,31,32,35,38-41). Of those who experienced treatment toxicities, 64.3% (38-79%) were considered mild and resolved without intervention (31,35,39,40).

The most frequent clinical toxicities were abdominal pain 40% (4-100%), nausea and vomiting 27% (6.1-95%), and fatigue 19% (0-75%) (17-19,26,27,34,37). The incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers was 3% (0-20%) and did not require invasive treatment (17,18,26,27,32,37). Only one study by Shitara et al. reported 5% of perforated duodenal ulcer resulting in discontinuation of therapy (41). Serological toxicities included hematological abnormalities and deranged liver function test (LFT) results. Other complications reported were hepatic abscesses, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and pulmonary embolism. Importantly, there were no deaths due to treatment toxicities.

Prognostic factors (Table 5)

Table 5. Clinical and pathological factors associated with poorer overall survival on univariate analysis.

| Factors | Association with poorer overall survival |

|

|---|---|---|

| Significant | Non-significant | |

| Tumor type (infiltrating vs. peripheral) | aMouli (26), aSaxena (17), Gusani (35): 3 studies | Vogl (30), Kim (36): 2 studies |

| ECOG | aHoffman (19) (0 vs. 1,2), aSaxena (17) (0 vs. ≥1), aIbrahim (0 vs. 1,2) (18): 3 studies | Park (32): 1 study |

| Number of lesions (multifocal) | aMouli (26): 1 study | Vogl (30): 1 study |

| Location of lesions | Park (32), Kim (36) | |

| Tumor burden | aHoffman (19): 1 study | Park (32): 1 study |

| Tumor hypovascularity | Kim (36), Vogl (30): 2 studies | Park (32): 1 study |

| Extra-hepatic disease | Park (32): 1 study | Kiefer (31): 1 study |

| RECIST | aHoffman (19) (partial response P<0.001), Gusani (35), Park (32), Vogl (stable disease P<0.001) (30): 4 studies | |

| TACE regime | Gusani (35) [gemcitabine-cisplatin vs. gemcitabine alone (13.8 vs. 6.3 months, P=0.0005]: 1 study | Vogl (30): 1 study |

| Treatment regimes | ||

| TACE vs. TACI vs. TACE + TACI | Kim (TACI alone P<0.001) (36): 1 study | |

| TACE + DEBTACE vs. TACE or systemic chemotherapy | Kuhlmann (29): 1 study | |

| Child pugh class (B vs. A) | Vogl (Child Pugh B) (30): 1 study | Kim (36): 1 study |

| Previous chemotherapy | aHoffman (19): 1 study | |

| Previous surgery | aHoffman (19): 1 study | |

| Portal vein thrombosis | aIbrahim (18): 1 study | |

a, SIRT. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; APE, acute pulmonary edema; CTx, systemic chemotherapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; DEBTACE, irinotecan drug eluting beads; LFT, liver function test; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; TACI, trans-arterial chemoinfusion.

Increased multiplicity, localization and vascularity of the tumor were identified as factors associated with poor overall survival (17,26,30,35,43). Whilst multiple and infiltrating tumor was a negative prognostic factor for SIRT, Mouli, 2013 #114; Saxena, 2010 #35; Hoffmann, 2012 #21 hypovascularity of the tumor was associated with poor outcome with TACE (30,43). Worse performance status as measured by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale was a significant prognostic factor in studies assessing SIRT but not in those with chemotherapy-based treatments (17-19). Data on prognostic factors was scarce and there was inconsistency across the studies.

Discussion

Summary of evidence and interpretation

The ideal approach to treatment of inoperable disease is poorly defined. TAE therapies are a novel and increasingly performed approach for treating unresectable ICC. Outcomes are promising, but there is no standardized protocol for treatment regime, combination of agents and patient selection. Studies have examined clinical outcomes of various chemotherapeutic and radioactive agents, on their own or in combinations, but with inconsistent results (29,30,35). Combination treatment of TACE and TACI has also been reported (23,43). A potential alternative to Y90 radioembolization is DEBTACE. Four studies in this review have compared this treatment with conventional TAE therapies (29,34,38,40).

Patient characteristics of the studies summarized in this review confirm that trans-arterial therapies are offered to a variety of patients with incurable disease. A significant proportion of patients in this review had advanced disease with bilobar tumors and extra-hepatic metastases. About 35% to 100% of patients received chemotherapy prior to trans-arterial treatment. In 10% to 40% of patients, hepatic resection had already been performed. The survival benefit achieved by trans-arterial therapies across a variety of patient groups shows these treatments are highly effective. However, the inconsistencies in patient demographics reflect the lack of specific patient selection criteria for trans-arterial therapies and results should be interpreted in the context of this potential bias.

Our review showed that TACE, TACI and SIRT achieved similar rates of tumor response in unresectable ICC (Table 3). Seven studies used radioembolization (17-19,26,27,38,39). Although none of these studies reported complete tumor response, rates for partial and stable response (SR) were higher than the average value reported by studies using chemoembolization. Overall and 1-year survival rates were also similar between the chemotherapy-based and radiotherapy-based approaches. Median overall survival was 13 months. This is higher than median overall survival of 11 months for systemic chemotherapy, reported in the recent metaanalysis (11). In two studies, tumor reduction following trans-arterial therapy allowed surgical resection of the tumor (23,40). Surgical resection following trans-arterial therapy allows the possibility of cure for previously unresectable ICC.

With advances in treatment techniques and clinical outcome, recent focus has shifted to maximizing clinical efficacy by using combination of trans-arterial approaches, drugs and radioactive agents. Combination of various chemoinfusion and TACE protocols was applied upon case-by-case assessments by Burger et al., who reported the highest overall survival of 30 months (23). However, their study was limited by a small sample size and absence of control groups. Another study by Kim et al. supports that combination therapy may enhance efficacy of TACI (36). Whilst TACI alone was a significant negative prognostic factor for overall survival, concomitant TACI and TACE achieved similar clinical success toTACE alone (36). Kuhlmann et al. compared systemic chemotherapy, TACE and DEBTACE, and found that combination therapy with TACE and DEBTACE is superior to both TACE and systemic chemotherapy alone (29).

Chemotherapy agents used across 13 studies using TACE and/or TACI varied widely; drugs included cisplatin, doxorubicin, gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, mitomycin C and oxaliplatin. Results on the optimal drug combination are controversial. Gusani et al. stated combination therapy using gemcitabine/cisplatin/oxaliplatin were most beneficial for overall survival (35), but another study found no significant differences among drug combinations (30). Overall survival of 23 and 21 months were demonstrated in studies using oxaliplatin (33) and mitomycin (37), respectively. However, a quantitative analysis is needed to assess its significance.

There are many studies analyzing predictors of survival in resectable ICC (44,45), but data is limited on trans-arterial treatment of inoperable disease. Identifying prognostic factors can optimize patient selection and improve treatment outcomes. Currently, patient selection criteria for trans-arterial therapies are unclear (17,36). Prognostic factors differed between chemo- and radio-embolization. ECOG status prior to treatment (17,19), multiple or bilobar tumors (26) and greater tumor burden/volume (19) were negatively associated with SIRT outcomes whereas hypovascularity of the tumor (30,36) and extra-hepatic involvements (32) were predictors of poor prognosis with TACE. Poor Child Pugh Class at treatment was also associated with poorer outcomes after TACE (30). These observations may be related to the rationale behind the different trans-arterial approaches. TACE exploits the fact that tumor draws most of its blood supply from the hepatic artery; hypervascular tumor may allow greater drug delivery and hence higher drug concentration (5). However, in light of the overall benefits of TAE and inadequate evidence, patients with hypovascular tumour should not be denied therapy until more evidence is acquired (36). SIRT delivers radioactive particles selectively and deeply within the tumor bed, hence greater tumor volume and multiplicity may require higher radiation doses and wider range of exposure risking unwanted toxicity (5). Assessment of tumor vascularity in TACE and measurement of tumor burden may identify ideal treatment options for patients with unresectable ICC.

TAE is safe with mild to moderate toxicity. Overall 30-day mortality in this study was 0.6% which is consistent with the most recent rate of 0.7% reported in a meta-analysis (16). Studies in our review reported acute toxicity rate of 34.9%. The majority of post-procedural complications was within 30 days and resolved without intervention. The most common types of adverse effects in both chemo- and radio-embolization were abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting and fatigue. Mild to moderate gastrointestinal ulcers and derangements in liver function were also relatively common. Haematological complications were more prevalent following TACE and systemic chemotherapy (CTx). Hepatic abscesses were also only observed in patients undergoing TACE (34,35,46). This may be confounded by the higher prevalence of hematological toxicities including neutropenia. Although the trans-arterial approach allows more targeted delivery of drugs and radiation without unwanted toxic exposure, a degree of systemic toxicity may be inevitable. Nonetheless, delayed toxicity was not recorded in any of the studies and acute complications were mostly mild and resolved spontaneously. The reporting of adverse events was inconsistent between studies and not all studies graded treatment toxicity. There was also discrepancy in the acuity of complications. A standardized approach to assessment of adverse outcomes may be useful to allow more accurate comparisons of safety data.

Despite the growing evidence on the therapeutic potential of TAE, there is only one systematic review to date evaluating the safety and efficacy of only chemotherapy-based treatments (16). However, in that study, no limitations in study design or publication dates were applied in their search, and the final selection of studies included abstracts for meetings and conferences. Although our study does not include a metaanalysis, we opted for meticulous selection of eligible studies using specific search criteria. In addition, meta-analysis of inappropriate and significantly heterogeneous data is not a necessary part of systematic reviews and the results of any metananalysis of such data should be interpreted with caution (47). To our knowledge, this is also the first review to assess all modalities of trans-arterial therapy including radioembolization.

Review limitations

The main limitation of this study was that meta-analysis could not be performed due to statistical, methodological and clinical heterogeneity. In particular, the heterogeneity of patient demographics, tumor pathology and treatment modality resulted in significant variation in results. Much of this is due to the lack of standardized treatment protocols. However, this review summarizes the best available evidence and provides useful information on the efficacy and safety of trans-arterial therapies for unresectable ICC.

Guidelines for future studies

This review demonstrates the lack of appropriate and consistent data required for meta-analysis. Prospective studies with pre-determined and standardized data assessment will be needed. This will facilitate consistent patient selection criteria and outcome measures providing appropriate volume and quality of data to accurately assess patient and disease characteristics and treatment outcomes including safety profile. There was no randomized controlled trial on trans-arterial therapies identified by our search. Future randomized studies are required to assess efficacy of combined trans-arterial therapies and the use of adjuvant systemic therapies in trans-arterial therapies. Specific drug combinations and therapy protocols need to be investigated further to assess the ideal treatment option for patients.

Conclusions

Trans-arterial therapies are safe and effective treatment options for unresectable ICC. They confer improvement in overall survival and achieve tumor reduction, allowing curative surgical resection in some cases. Although no specific patient selection criteria or prognostic factors for treatment success exists, the results of this review suggest that there are various patient and disease factors associated with clinical outcome. In the absence of large randomised controlled trials, these findings must be considered in conjunction with clinical decision making tailored to each patient.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet 2005;366:1303-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park J, Kim MH, Kim KP, et al. Natural History and Prognostic Factors of Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma without Surgery, Chemotherapy, or Radiotherapy: A Large-Scale Observational Study. Gut liver 2009;3:298-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou FF, Sheen-Chen SM, Chen YS, et al. Surgical treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 1997;44:760-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson CD, Pinson CW, Berlin J, et al. Chari RS. Diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Oncologist 2004;9:43-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong K, Geschwind JF. Locoregional intra-arterial therapies for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Oncol 2010;37:110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieser MJ, Barry MK, Rowland C, et al. Surgical management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a 31-year experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 1998;5:41-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtsuka M, Ito H, Kimura F, et al. Results of surgical treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and clinicopathological factors influencing survival. Br J Surg 2002;89:1525-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber SM, Jarnagin WR, Klimstra D, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: resectability, recurrence pattern, and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 2001;193:384-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thongprasert S. The role of chemotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Oncol 2005;16 Suppl 2:ii93-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1273-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valle JW, Furuse J, Jitlal M, et al. Cisplatin and gemcitabine for advanced biliary tract cancer: a meta-analysis of two randomised trials. Ann Oncol 2014;25:391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosconi S, Beretta GD, Labianca R, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2009;69:259-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramírez-Merino N, Aix SP, Cortes-Funes H. Chemotherapy for cholangiocarcinoma: An update. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2013;5:171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown KM, Parmar AD, Geller DA. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2014;23:231-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada R, Nakatsuka H, Nakamura K, et al. Hepatic artery embolization in 32 patients with unresectable hepatoma. Osaka City Med J 1980;26:81-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray CE, Jr, Edwards A, Smith MT, et al. Metaanalysis of survival, complications, and imaging response following chemotherapy-based transarterial therapy in patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24:1218-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxena A, Bester L, Chua TC, et al. Yttrium-90 radiotherapy for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a preliminary assessment of this novel treatment option. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:484-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibrahim SM, Mulcahy MF, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Treatment of unresectable cholangiocarcinoma using yttrium-90 microspheres: results from a pilot study. Cancer 2008;113:2119-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann RT, Paprottka PM, Schon A, et al. Transarterial hepatic yttrium-90 radioembolization in patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: factors associated with prolonged survival. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2012;35:105-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Altman DG, Liberati A, et al. PRISMA statement. Epidemiology 2011;22:128; author reply 128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geschwind JF. Chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: where does the truth lie? J Vasc Interv Radiol 2002;13:991-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, et al. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using Yttrium-90 microspheres: a comprehensive report of long-term outcomes. Gastroenterology 2010;138:52-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burger I, Hong K, Schulick R, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in unresectable cholangiocarcinoma: initial experience in a single institution. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2005;16:353-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, et al. Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg 1998;228:385-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2001;234:507-17; discussion 17-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mouli S, Memon K, Baker T, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: safety, response, and survival analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24:1227-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haug AR, Heinemann V, Bruns CJ, et al. 18F-FDG PET independently predicts survival in patients with cholangiocellular carcinoma treated with 90Y microspheres. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38:1037-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheuermann U, Kaths JM, Heise M, et al. Comparison of resection and transarterial chemoembolisation in the treatment of advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma--a single-center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39:593-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhlmann JB, Euringer W, Spangenberg HC, et al. Treatment of unresectable cholangiocarcinoma: conventional transarterial chemoembolization compared with drug eluting bead-transarterial chemoembolization and systemic chemotherapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;24:437-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogl TJ, Naguib NN, Nour-Eldin NE, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization in the treatment of patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinoma: Results and prognostic factors governing treatment success. Int J Cancer 2012;131:733-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiefer MV, Albert M, McNally M, et al. Chemoembolization of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with cisplatinum, doxorubicin, mitomycin C, ethiodol, and polyvinyl alcohol: a 2-center study. Cancer 2011;117:1498-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SY, Kim JH, Yoon HJ, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization versus supportive therapy in the palliative treatment of unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Radiol 2011;66:322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poggi G, Amatu A, Montagna B, et al. OEM-TACE: a new therapeutic approach in unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2009;32:1187-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aliberti C, Benea G, Tilli M, et al. Chemoembolization (TACE) of unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with slow-release doxorubicin-eluting beads: preliminary results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008;31:883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gusani NJ, Balaa FK, Steel JL, et al. Treatment of unresectable cholangiocarcinoma with gemcitabine-based transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE): a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:129-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JH, Yoon HK, Sung KB, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization or chemoinfusion for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: clinical efficacy and factors influencing outcomes. Cancer 2008;113:1614-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herber S, Otto G, Schneider J, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for inoperable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007;30:1156-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyder O, Marsh JW, Salem R, et al. Intra-arterial therapy for advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis. Ann Sur Oncol 2013;20:3779-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rafi S, Piduru SM, El-Rayes B, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for unresectable standard-chemorefractory intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: survival, efficacy, and safety study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2013;36:440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schiffman SC, Metzger T, Dubel G, et al. Precision hepatic arterial irinotecan therapy in the treatment of unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma: optimal tolerance and prolonged overall survival. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:431-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shitara K, Ikami I, Munakata M, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of mitomycin C with degradable starch microspheres for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.NHMRC. NHMRC additional levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines. 2009. Available online: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/guidelines/stage_2_consultation_levels_and_grades.pdf

- 43.Kim JH, Yoon HK, Kim SY, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization vs. chemoinfusion for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with major portal vein thrombosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:1291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murakami S, Ajiki T, Okazaki T, et al. Factors affecting survival after resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Today 2014;44:1847-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Campagnaro T, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic factors after surgical resection. World J Surg 2009;33:1247-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim JS, Park SW, Choi TH, et al. The evaluation of relevant factors influencing skin graft changes in color over time. Dermatologic surgery: official publication for American Society for Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:32-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. England: Wiley, 2008:633. [Google Scholar]