Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is a highly heterogeneous disorder encompassing several distinct forms with different clinical manifestations including a wide spectrum of age at onset. Despite many advances, the causal genetic defect remains unknown for many subtypes of the disease, including some of those forms with an apparent Mendelian mode of inheritance. Here we report two loss-of-function mutations (c.1655T>A [p.Leu552∗] and c.280G>A [p.Asp94Asn]) in the gene for the Adaptor Protein, Phosphotyrosine Interaction, PH domain, and leucine zipper containing 1 (APPL1) that were identified by means of whole-exome sequencing in two large families with a high prevalence of diabetes not due to mutations in known genes involved in maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY). APPL1 binds to AKT2, a key molecule in the insulin signaling pathway, thereby enhancing insulin-induced AKT2 activation and downstream signaling leading to insulin action and secretion. Both mutations cause APPL1 loss of function. The p.Leu552∗ alteration totally abolishes APPL1 protein expression in HepG2 transfected cells and the p.Asp94Asn alteration causes significant reduction in the enhancement of the insulin-stimulated AKT2 and GSK3β phosphorylation that is observed after wild-type APPL1 transfection. These findings—linking APPL1 mutations to familial forms of diabetes—reaffirm the critical role of APPL1 in glucose homeostasis.

Main Text

Diabetes mellitus (DM [MIM: 125853]) is the most common metabolic disorder, imposing a worldwide burden on morbidity and mortality arising from its chronic complications.1 Rather than being a single disorder, DM encompasses several distinct forms characterized by different clinical manifestations including a wide spectrum of age at onset.2 Such clinical heterogeneity is paralleled by a marked genetic heterogeneity. Several disease genes have been identified for some monogenic forms of the disease such as “maturity-onset diabetes of the young” (MODY [MIM: 606391]) and neonatal diabetes (ND [MIM: 606176]).2,3 However, despite these advances, the causal genetic defect remains unknown for many subtypes of the disease, including some of the forms with an apparent Mendelian mode of inheritance. Filling this knowledge gap would be extremely useful because it would allow the development of predicting tools as well as novel treatments tailored to specific etiological mechanisms. During the past few years, whole-exome sequencing (WES), made possible by the advent of “next-generation” array-based sequencing methods, has emerged as a powerful and cost-effective strategy to achieve this goal.4

Here we describe two loss-of-function mutations in the gene for the Adaptor Protein, Phosphotyrosine Interaction, PH domain, and leucine zipper containing 1 (APPL1 [MIM: 604299]) that were identified through the WES approach in two large families with a high prevalence of diabetes not due to mutations in known MODY genes5,6 (S. Prudente et al., 2014, American Diabetes Association, 74th Scientific Sessions, abstract). WES was performed in 60 families (52 from the US and 8 from Italy) selected on the basis of the following criteria: (1) presence of overt diabetes in at least three consecutive generations with an apparent dominant transmission, (2) a proband and at least one first-degree relative with diabetes diagnosed before age 35, (3) diabetes entering the family from only one side, and (4) lack of mutations in the six most common MODY genes7 (HNF4A [MIM: 600281], GCK [MIM: 138079], HNF1A [MIM: 142410], PDX1 [MIM: 600733], HNF1B [MIM: 189907], and NEUROD1 [MIM: 601724]) as determined by Sanger sequencing. Study protocols and informed consent procedures were approved by the local Institutional Ethic Committees in Italy and the US and all participants gave written consent. This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2000. Family members were classified as having diabetes, pre-diabetes, or normal glucose tolerance based on the ADA 2014 criteria. For each family, WES was carried out in the proband and an additional diabetic member (both with age of disease onset <35 years) using DNA samples extracted from peripheral blood by standard procedures; in the Italian families, a non-affected individual with age >50 years was also included in the study. All protein-coding regions, as defined by RefSeq 67, were targeted. About 210,000 coding exons were captured from 3 μg of genomic DNA using the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon v.4+UTRs, the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon v.5, or the SeqCap EZ human Exome Library v.2.0 kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Whole-exome DNA libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq2000 (Illumina) in the US and a SOLID 5500XL (Life Technologies) in Italy. After mapping the short-reads to the GRCh37/hg19 human assembly by means of BWA8 and SAMtools9 or LifeScope (Life Technologies),10 variants were detected by means of GATK11 and filtered to include only those with ≥5× or ≥8× depth of coverage as obtained by HiSeq or SOLID, respectively, and per-base and mapping quality phred values exceeding 30.

A total of 453,415 and 250,174 variants were identified in the US and Italian families, respectively (Table S1). Of these, 365,984 and 158,695, respectively, passed the primary QC filters. Homozygous variants, variants reported as validated polymorphisms with frequency >0.01 in publicly available human variation resources (dbSNP142, 1000 Genomes, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project Exome Variant Server [EVS]), and variants not shared by both affected individuals were filtered out. Of the remaining variants, 7,972 and 644, respectively, were potentially deleterious, being nonsense, frameshift, or missense, or affecting splicing sites (Table S1). These variants were stratified through a mixed filtering/prioritization strategy taking into account the predicted impact of each variant12 and the functional relevance of the corresponding genes with regard to diabetes. At the end of this process, described in detail in Figure S1, 35 variants in 28 genes and 4 variants in 3 genes were prioritized in the US and Italian datasets, respectively. The prioritized genes are listed in Table S2. One of them (APPL1, GenBank: NM_012096.2 and NP_036228.1) was present in both the Italian and US prioritization lists and, as such, was investigated further by Sanger sequencing and bioinformatic and functional studies. A nonsense mutation (c.1655T>A [p.Leu552∗]) was identified in this gene in one of the Italian families whereas a missense substitution (c.280G>A [p.Asp94Asn]) was found in one of the US families (Figure S2). None of the other prioritized variants were found in these two families. These other variants are being investigated by Sanger sequencing in the families in which they were originally identified to determine whether they segregate with diabetes according to an autosomal-dominant mode of inheritance.

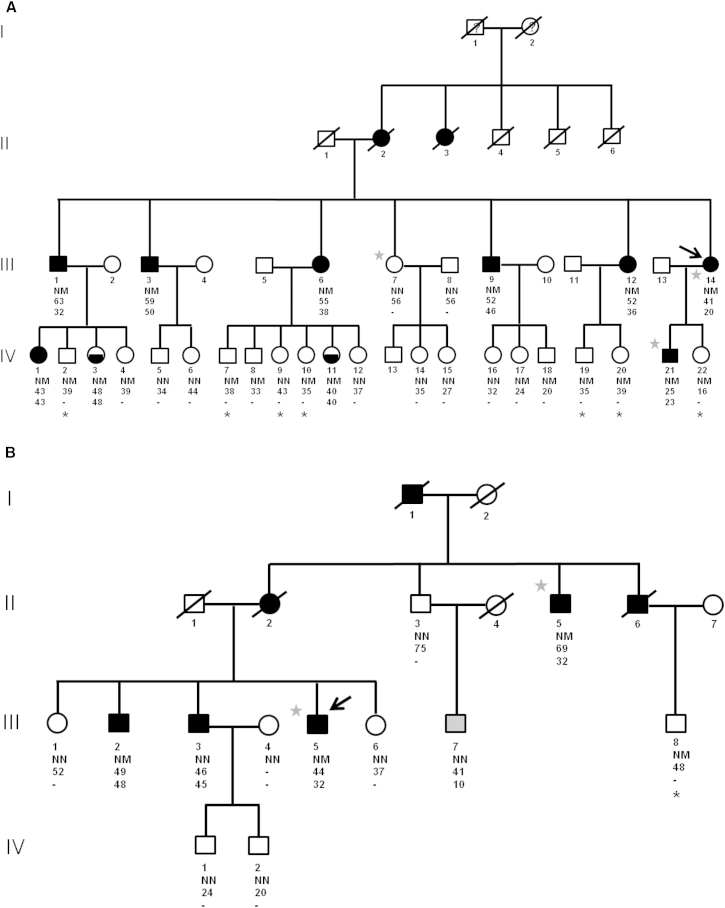

Clinical features of the members of the two families with APPL1 mutations are shown in Tables 1 and S3. In the Italian family, the p.Leu552∗ alteration was found in all the ten members with diabetes or pre-diabetes (Figure 1A). Eight of the individuals who did not have overt diabetes at examination (n = 19) did not have the mutation and the remaining were carriers (Figure 1A). Of note, most of the unaffected carriers were younger than 38 years (the median age at diabetes diagnosis among affected members) and were still at risk of developing diabetes in the future, especially considering that the presence of pre-diabetes could not be excluded in most of them due to the lack of oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) data. It is also conceivable that the concomitant presence of a specific environment and/or other “modifier” genes is needed for this mutation to be fully penetrant—a scenario that has been observed for several human inherited diseases including familial diabetes.13–16 In this context, it is noteworthy that all non-affected subjects carrying the mutation belonged to the youngest generation. Although, in general, the environment has become more diabetogenic over the years, it is conceivable that, as compared to previous generations, young people from such heavily affected families might be paying more attention to a salutary lifestyle such as a proper diet and physical activity. This possibility is supported by the observation that in each affected subject of the youngest generation, diabetes was diagnosed at an older age (8 years on average) as compared to his/her affected parent.

Table 1.

Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of Examined Members from the Italian and US Families

| Family Member | Mutation Carrier | Gender | Age (years) | Age at Diagnosis (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Glycemic Status | Current Treatment | FPG | PG 2 hr after OGTT | HbA1c (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family: Italian | ||||||||||

| III-1 | yes | M | 63 | 32 | 29.73 | DM | ins | NA | NA | 6.7 |

| IV-1 | yes | F | 43 | 43 | 29.05 | DM | diet | 179 | NA | 7 |

| IV-2 | yes | F | 39 | – | 31.59 | NG | – | 63 | NA | 4.5 |

| IV-3 | yes | F | 48 | 48 | 32.81 | PD | diet | 92 | NA | 5.8 |

| IV-4 | yes | M | 39 | – | 31.64 | NG | – | 86 | 74 | NA |

| III-2 | yes | M | 59 | 50 | 29.41 | DM | diet | 153 | NA | NA |

| IV-5 | no | M | 34 | – | 25.61 | NG | – | 91 | 81 | 3.7 |

| IV-6 | no | F | 44 | – | 22.10 | NG | – | 95 | 108 | 3.8 |

| III-6 | yes | F | 55 | 38 | 25.65 | DM | ins | 315 | NA | NA |

| IV-7 | yes | M | 38 | – | 28.67 | NG | – | 78 | NA | 3.5 |

| IV-8 | yes | M | 33 | – | 27.13 | NG | – | 98 | 121 | 3.8 |

| IV-9 | no | F | 43 | – | 21.11 | NG | – | 77 | NA | 4.7 |

| IV-10 | yes | F | 35 | – | 21.72 | NG | – | 81 | NA | 3.4 |

| IV-11 | yes | F | 41 | 40 | 24.16 | PD | diet | 98 | 169 | 5.7 |

| IV-12 | no | F | 37 | – | 29.30 | NG | – | 87 | 116 | NA |

| III-7 | no | F | 56 | – | 26.64 | NG | – | 98 | 118 | NA |

| IV-14 | no | F | 35 | – | 26.37 | NG | – | 86 | 119 | 5.6 |

| IV-15 | no | F | 27 | – | 23.58 | NG | – | 76 | 75 | NA |

| III-9 | yes | M | 52 | 46 | 27.94 | DM | OHA | 162 | NA | NA |

| IV-16 | no | F | 32 | – | 34.77 | NG | – | 75 | 103 | NA |

| IV-17 | yes | F | 24 | – | 25.77 | NG | – | 80 | 91 | NA |

| IV-18 | yes | M | 30 | – | 28.41 | NG | – | 78 | 70 | NA |

| III-12 | yes | F | 52 | 36 | 28.52 | DM | ins | NA | NA | NA |

| IV-19 | yes | M | 35 | – | 24.93 | NG | – | 78 | NA | 3.2 |

| IV-20 | yes | F | 39 | – | 24.17 | NG | – | 83 | NA | 5.2 |

| III-14 | yes | F | 41 | 20 | 30.48 | DM | ins | 434 | NA | NA |

| IV-21 | yes | M | 25 | 23 | 25.35 | DM | OHA | 252 | NA | 7.7 |

| IV-22 | yes | F | 16 | – | 37.73 | NG | – | 86 | NA | NA |

| Family: US | ||||||||||

| II-3 | no | M | 75 | – | 27.26 | NG | – | 92 | NA | NA |

| III-7 | no | M | 41 | 10 | 23.01 | DM | ins | NA | NA | NA |

| II-5 | yes | M | 69 | 32 | 25.74 | DM | ins | NA | NA | NA |

| III-1 | no | F | 52 | – | 40.76 | NG | – | 97 | NA | NA |

| III-2 | yes | M | 49 | 48 | 27.33 | DM | ins | NA | NA | NA |

| III-3 | no | M | 46 | 45 | 27.33 | DM | ins | 102 | NA | 6.4 |

| III-4 | no | F | 47 | – | 22.05 | NG | – | 68 | NA | 5.4 |

| IV-1 | no | M | 24 | – | 24.37 | NG | – | 75 | NA | 4.9 |

| IV-2 | no | M | 20 | – | 23.01 | NG | – | 81 | NA | 5.1 |

| III-5 | yes | M | 44 | 32 | 30.75 | DM | ins | NA | NA | 11.8 |

| III-6 | no | F | 37 | – | 35.50 | NG | – | 95 | NA | NA |

| III-8 | yes | M | 48 | – | 28.01 | NG | – | 72 | 62 | 5.4 |

Abbreviations are as follows: BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; ins, insulin; NA, not available; NG, normal glucose; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; OHA, oral antidiabetic agents; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; PD, pre-diabetes (as indicated by HbA1c ≥ 5.7%, according to ADA criteria).

Figure 1.

Pedigree Structures of the Two Families with APPL1 Mutations

Shown are families from Italy (A) and from the US (B). Round and square symbols denote females and males, respectively. Filled and open symbols denote diabetic and non-diabetic subjects, respectively; half-filled symbols denote individuals with pre-diabetes (see definition in the text). The arrow points to the proband. Gray stars indicate family members in which WES was performed. Black stars indicate those individuals who did not undergo OGTT. Gray symbol denotes individual with type 1 diabetes. NM denotes presence of heterozygous APPL1 mutations (p.Leu552∗ in the Italian family, p.Asp94Asn in the US family); NN denotes absence of such mutations. The age at examination is reported for each individual under the corresponding symbol; the age at diagnosis is reported for diabetic or prediabetic individuals under the age at examination.

In the US family, the p.Asp94Asn alteration was found or inferred to be present in five of the seven family members with diabetes (Figure 1B). One of the diabetic members who did not carry the mutation (III-7) had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at age 10; the other one (III-3) might have had the common, multifactorial form of type 2 diabetes, which is highly prevalent (12.3%) in the adult US population.17 A non-penetrant subject (III-8) was observed in the youngest generation also in this family (Figure 1B).

Both APPL1 p.Asp94Asn and p.Leu552∗ alteration were not present in the database from the Exome Sequencing Project (EVS, n = 6,503) or in the larger Exome Aggregation Consortium database (ExAC, n = 61,486). In addition, we could not find either alteration among 1,639 non-diabetic and 2,970 T2D-affected unrelated individuals of European ancestry we previously described.18

No additional mutations were found by Sanger sequencing within the entire APPL1 coding region (consisting of 22 exons, Table S4) in the probands of 54 additional Italian kindreds with familial diabetes in which WES has not been performed yet.

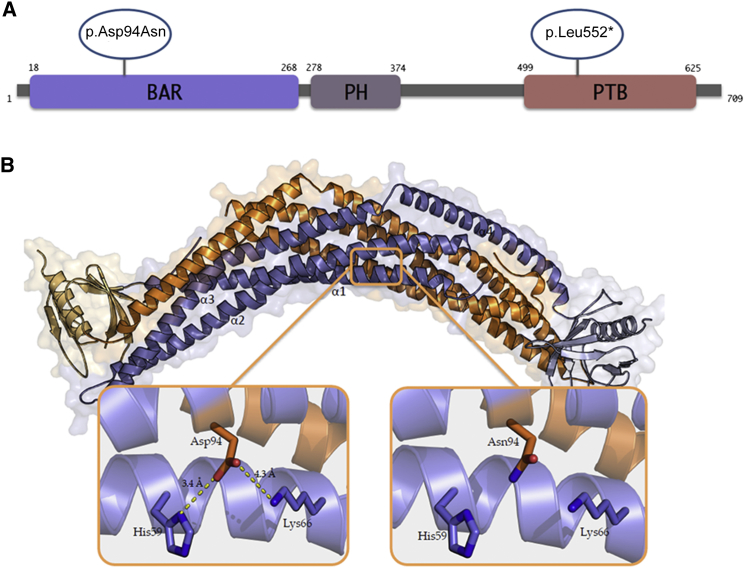

APPL1 is an anchor protein consisting of 709 amino acids with multiple functional domains, including a Bin1/amphiphysin/rvs167 (BAR) domain, a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, and a phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain19 (Figure 2A). As an adaptor protein, APPL1 interacts with several proteins including critical components of the insulin-signaling pathway.20–22 In agreement with this, several studies of mice models have clearly demonstrated a fundamental role for this protein in glucose homeostasis.20,21,23–25 Of particular importance in this regard is APPL1’s interaction with AKT (MIM: 164731) in competition with the AKT endogenous inhibitor TRIB3 (MIM: 607898).20 By virtue of its binding with APPL1 rather than TRIB3, AKT can be translocated to the plasma membrane, where it can be phosphorylated and activated, thereby propagating the insulin signal.21,22

Figure 2.

In Silico Prediction of the Effects of the Identified APPL1 Mutations

(A) Schematic representation of the domains of the APPL1 protein and position of the identified alteration. Abbreviations are as follows: BAR, Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs domain; PH, pleckstrin homology domain; PTB, phosphotyrosine-binding domain. Orange circles indicate the missense and the nonsense mutation at positions 94 and 552, respectively.

(B) Structure of the BAR-PH domain dimer of human APPL1 (PDB: 2Q13) and predicted effect of p.Asp94Asn alteration. One monomer is shown in orange, the other one in violet. The concave surface at the bottom is the lipid-binding surface enriched in positively charged residues, which is needed for the interaction with the plasma membrane. Asp94, located on the α2 helix, and the positively charged residues (His59 and Lys66), located on the α1 helix, are represented by sticks. Interactions and atomic distances between residues are visualized by yellow dashed lines. The substitution of the negatively charged amino acid Asp94 with a neutral one (Asn94) disrupts salt bridges with His59 and Lys66 (right). Inspection, measurement, and rendering were made with PyMOL software.

The nonsense APPL1 alteration p.Leu552∗ is located in the PTB domain (aa 499–625, Figure 2A), which has been shown to bind the AKT catalytic domain.26 The introduction of a premature stop codon at position 552 leads to the deletion of most of the PTB domain, thereby making APPL1 unable to bind AKT (Figure S3).

The missense mutation affects the aspartic acid residue at position 94 (i.e., Asp94), which resides on the concave surface of the APPL1 BAR domain (Figure 2) and is highly conserved among species (Figure S3). Sequence-based tools do not provide unequivocal answers about a pathogenic effect of an aspartic acid (Asp) to asparagine (Asn) substitution at this position. However, structure-based tools suggest that this mutation causes a protein structure destabilization that is likely to have functional consequences (Table S5). Structural and biochemical studies have shown that APPL proteins, including both APPL1 and its homolog APPL2 (MIM: 606231), are able to dimerize, forming homodimers (APPL1-APPL1 and APPL2-APPL2) as well as heterodimers (APPL1-APPL2).27 All the homotypic and heterotypic APPL-APPL interactions are mediated by their BAR domains, which are also necessary for the association with curved cell membranes.27,28 The BAR dimer concave surface, lined with positively charged residues, is responsible for the interaction of this domain with the plasma membrane.29–32 In agreement with this, mutations localized to this surface have been reported to abolish APPL1 ability to bind the plasma membrane.33,34 The structural model of the APPL1 BAR domain (PyMOL) predicts that the substitution of a negatively charged amino acid (Asp94) with a neutral one (Asn94) disrupts salt bridges with residues His59 and Lys66 (Figure 3), thereby altering the BAR domain structural stability and possibly affecting its ability to dimerize as well as to bind the plasma membrane.

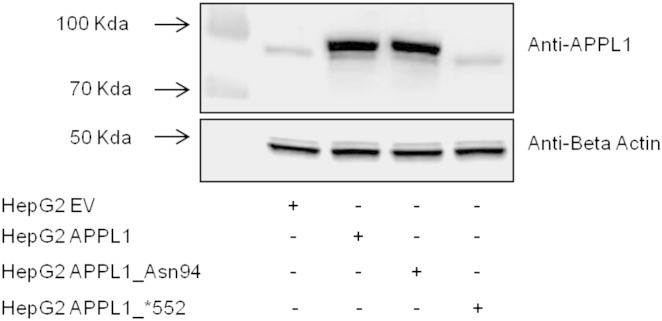

Figure 3.

In Vitro Effects of the APPL1 Mutations on Protein Levels

HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with APPL1, APPL1_Asn94, APPL1_∗552, or empty vector (HEPG2_EV). After 48 hr transfection, cells were lysed and APPL1 and BETA ACTIN lower blot expression were evaluated by immunoblot analyses. In brief, equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-APPL1 (Cell Signaling) and anti-BETA ACTIN (Santa Cruz Biotechnology)-specific antibodies. A representative blot is shown.

To evaluate the impact of the two APPL1 mutations on insulin-mediated AKT activation and downstream signaling, APPL1 carrying the p.Leu552∗ or the p.Asp94Asn alteration were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of a pCMV6-Entry APPL1 myc tagged cDNA (Origene) and expressed in HepG2 cells (ATCC). These cells were chosen because they are (1) of human origin, (2) very insulin-responsive, and (3) isolated from liver, a central organ in the maintenance of in vivo glucose homeostasis. Cells were kept at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS, were transiently transfected with APPL1 cDNA pCMV6 constructs carrying the wild-type sequence (HepG2 APPL1), the ∗552 alteration (HepG2 APPL1_∗552), or the Asn94 alteration (HepG2 APPL1_Asn94) by using TransIT reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Mirus). As compared to cells transfected with a control empty vector (HepG2_EV), cells transfected with any of the APPL1 cDNA constructs showed significant increase in APPL1 mRNA levels (as evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR), indicating that RNA stability was not negatively affected by these mutations (Table S6). In HepG2 APPL1 and APPL1_Asn94 cells, the mRNA increase was paralleled by an increase in APPL1 protein levels. By contrast, in HepG2 APPL1_∗552 cells, the APPL1 protein was almost undetectable, possibly due to instability and rapid degradation of the truncated protein (Figure 3). This result was confirmed with three different antibodies raised against three different APPL1 epitopes (data not shown). Given the lack of APPL1 protein expression caused by the p.Leu552∗ alteration, HepG2 APPL1_∗552 cells were not studied any further with regard to insulin signaling.

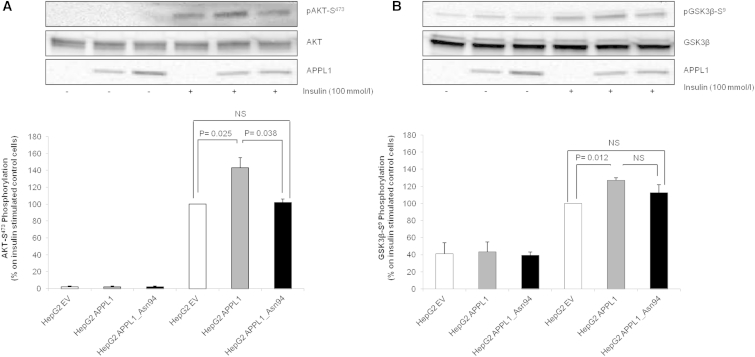

After insulin stimulation (100 nmol/l for 5 min) and cell lysis, equal amounts of protein were analyzed by immunoblot with specific antibodies against APPL1, phospho-AKT-S473, and phospho-GSK3β-S8 (Cell Signaling). The blots were then stripped and re-probed with antibodies against AKT and GSK3β (MIM: 605004; Cell Signaling) for normalization (Figure 4). In HepG2 APPL1 cells, insulin-induced AKT-S473 phosphorylation was increased by 47% as compared to HepG2_EV cells (p = 0.025) (Figure 4A). Such stimulatory effect of APPL1 was completely abolished by the Asn94 alteration (Figure 4A). Similarly, insulin-stimulated GSK3β-S8 phosphorylation was increased by 27% in HepG2 APPL1 cells as compared to HepG2_EV cells (p = 0.012) (Figure 4B). In HepG2 APPL1_Asn94 cells, this effect was blunted to the extent that insulin-stimulated GSK3β-S8 phosphorylation was no longer different from that in HepG2_EV control cells (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of APPL1_Asn94 Transfection on Akt-S473 and GSK3β-S8 Phosphorylation

HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with APPL1, APPL1_Asn94, or empty vector. After 48 hr, cells were stimulated with 100 nmol/l insulin for 5 min and then lysed. Phospho-AKT-S473 (A) or phospho-GSK3β-S8 (B) were evaluated by immunoblot analyses. In brief, equal amount of protein from cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-phospho-AKT-S473 (A, upper blot), anti-AKT (A, middle blot), anti-APPL1 (A and B, lower blot), or anti-phospho-GSK3β-S8 (B, upper blot) and anti-GSK3β (B, middle blot) specific antibodies, respectively. Gel images were acquired with Molecular Imager ChemiDoc XRS (Biorad) and analyzed with Kodak Molecular Imaging Software 4.0 or IMAGEJ 1.40 g (Wayne Rasband, NIH). A representative blot for each condition is shown. Bars represent the percentage of AKT-S473 phosphorylation/AKT OD ratio (A) or GSK3β-S8/GSK3β OD ratio (B) in insulin-stimulated control cells. Data are means ± SD of three experiments in separate times.

Taken together, these results suggest that both p.Leu552∗ and p.Asp94Asn are loss-of-function alterations, one determining a complete lack of expression of the mutated allele, the other causing decreased functionality of a normally expressed allele. Given the central role of AKT in insulin signaling, these results support a detrimental role of both mutations on insulin action and, potentially, insulin secretion.

In mice, APPL1 is widely expressed in all insulin target tissues and organs including the liver, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and pancreas.25 In the latter organ, the expression of APPL1 is higher in the islet than in the non-islet fraction (i.e., exocrine cells).24 In islets, APPL1 co-localizes with insulin, indicating that this protein is abundantly expressed in β cells where it acts as a physiological regulator of insulin secretion.24 Also in humans, APPL1 is expressed in all insulin target tissues and organs (as reported by the public atlas of gene expression and regulation across multiple human tissues generated by The Genotype-Tissue Expression project [GTEx]). As in mice, APPL1 expression is particularly enriched in human islets (as reported by the T1Dbase-Beta Cell Gene Atlas), although no specific data on β cells are available. To obtain further insights about the role of APPL1 on insulin secretion in humans, we measured APPL1 expression levels and glucose-induced insulin secretion in human islets from ten brain-dead multi-organ donors (five males, five females; BMI range: 19.4–34.8 kg/m2). None of the donors were diabetic, as indicated by the medical records obtained from the intensive care units (ICUs). Mean glucose levels under continuous glucose infusion in the ICU ranged from 63 to 192 mg/dl. Fructosamine levels were available for five out of ten individuals and ranged from 105 to 278 μmol/l (reference values for non-diabetic individuals: <285 μmol/l). APPL1 expression was significantly correlated with glucose-induced insulin secretion (Figure 5), suggesting that the positive role of APPL1 on insulin secretion reported in rodents23–25 is also operating in humans and reinforcing the possibility that human mutations reducing APPL1 expression levels or its function in insulin signaling might affect not only insulin sensitivity but also insulin secretion.

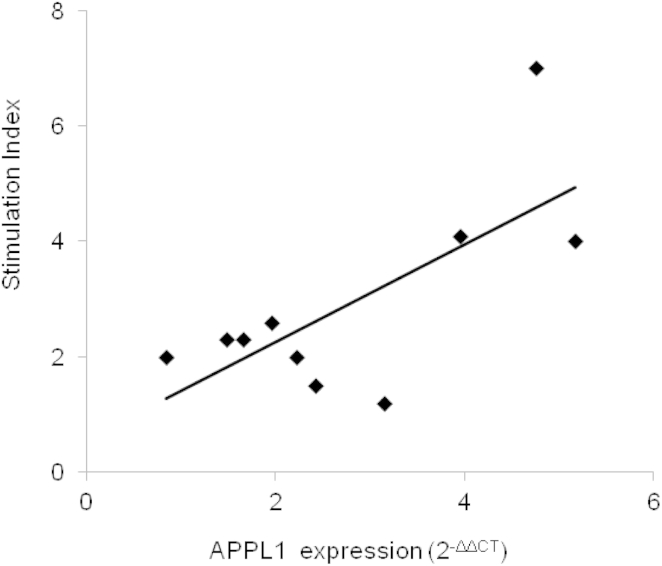

Figure 5.

Correlation between APPL1 Expression and Glucose-Induced Insulin Secretion in Human Islets

Pancreata were collected from ten non-diabetic brain-dead multiorgan donors (age: 65.2 ± 13.6 years; 50% females) and pancreatic islets were prepared as previously described.35 Glucose-induced insulin secretion was measured and then expressed as stimulation index (SI) calculated by dividing insulin release after glucose stimulation at 16.7 mmol/l over basal insulin release (i.e., at glucose 3.3 mmol/l). Prime Time Standard qPCR Assays (Integrated DNA Technologies) were used to quantify relative gene expression levels of APPL1, GAPDH (MIM: 138400), and BETA ACTIN (MIM: 102630) on ABI-PRISM 7900 (Applera Life Technologies). APPL1 expression was calculated by using the comparative ΔCT method. Relationship between SI and APPL1 expression was evaluated by Pearson’s correlation with SPSS 13 software. APPL1 expression was significantly associated with SI (r2 = 0.50, p = 0.022). This association remained significant also after adjusting for age and gender (p = 0.048).

In conclusion, this study describes APPL1 mutations as pathogenic factors for familial forms of diabetes. This finding is consistent with previous evidence from animal studies supporting a key regulatory role of APPL1 in glucose metabolism and points to this molecule as a potential target for future treatments aimed at preserving or restoring glucose homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the subjects and families involved in the study. This work was supported by the Italian Society of Diabetology (SID) (grant FO.RI.SID 2011 to S. Prudente), NIH (grant R01DK55523 to A.D. and P30 DK036836 to the Joslin Diabetes Research Center [Advanced Genomics and Genetics Core]), and the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente 2014 and 2015 to S. Prudente, R.D.P., and V.T.).

Published: June 11, 2015

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include four figures and six tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.011.

Contributor Information

Sabrina Prudente, Email: s.prudente@css-mendel.it.

Alessandro Doria, Email: alessandro.doria@joslin.harvard.edu.

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

1000 Genomes, http://browser.1000genomes.org

Clustal Omega, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/

CUPSAT, http://cupsat.tu-bs.de

Diabetes Atlas, http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

GTEx Portal, http://www.gtexportal.org/home/

I-Mutant, http://folding.biofold.org/i-mutant/i-mutant2.0.html

LifeScope, http://www.lifetechnologies.com/lifescope

Mutation Assessor, http://mutationassessor.org/

MutationTaster, http://www.mutationtaster.org/

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

PolyPhen-2, http://www.genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

PyMOL, http://www.pymol.org

RCSB Protein Data Bank, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do

T1DBase, https://www.t1dbase.org

WebLogo 3, http://weblogo.threeplusone.com

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Roglic G., Unwin N., Bennett P.H., Mathers C., Tuomilehto J., Nag S., Connolly V., King H. The burden of mortality attributable to diabetes: realistic estimates for the year 2000. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2130–2135. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaxillaire M., Froguel P. Monogenic diabetes in the young, pharmacogenetics and relevance to multifactorial forms of type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2008;29:254–264. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwitzgebel V.M. Many faces of monogenic diabetes. J. Diabetes Investig. 2014;5:121–133. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamshad M.J., Ng S.B., Bigham A.W., Tabor H.K., Emond M.J., Nickerson D.A., Shendure J. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doria A., Yang Y., Malecki M., Scotti S., Dreyfus J., O’Keeffe C., Orban T., Warram J.H., Krolewski A.S. Phenotypic characteristics of early-onset autosomal-dominant type 2 diabetes unlinked to known maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) genes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:253–261. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S.H., Warram J.H., Krolewski A.S., Doria A. Mutation screening of the neurogenin-3 gene in autosomal dominant diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:2320–2322. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fajans S.S., Bell G.I. MODY: history, genetics, pathophysiology, and clinical decision making. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1878–1884. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R., 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castellana S., Romani M., Valente E.M., Mazza T. A solid quality-control analysis of AB SOLiD short-read sequencing data. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;14:684–695. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M., DePristo M.A. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castellana S., Mazza T. Congruency in the prediction of pathogenic missense mutations: state-of-the-art web-based tools. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;14:448–459. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper D.N., Krawczak M., Polychronakos C., Tyler-Smith C., Kehrer-Sawatzki H. Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum. Genet. 2013;132:1077–1130. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1331-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonnefond A., Philippe J., Durand E., Dechaume A., Huyvaert M., Montagne L., Marre M., Balkau B., Fajardy I., Vambergue A. Whole-exome sequencing and high throughput genotyping identified KCNJ11 as the thirteenth MODY gene. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meur G., Simon A., Harun N., Virally M., Dechaume A., Bonnefond A., Fetita S., Tarasov A.I., Guillausseau P.J., Boesgaard T.W. Insulin gene mutations resulting in early-onset diabetes: marked differences in clinical presentation, metabolic status, and pathogenic effect through endoplasmic reticulum retention. Diabetes. 2010;59:653–661. doi: 10.2337/db09-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edghill E.L., Flanagan S.E., Patch A.M., Boustred C., Parrish A., Shields B., Shepherd M.H., Hussain K., Kapoor R.R., Malecki M., Neonatal Diabetes International Collaborative Group Insulin mutation screening in 1,044 patients with diabetes: mutations in the INS gene are a common cause of neonatal diabetes but a rare cause of diabetes diagnosed in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes. 2008;57:1034–1042. doi: 10.2337/db07-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta: 2014. Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prudente S., Morini E., Marselli L., Baratta R., Copetti M., Mendonca C., Andreozzi F., Chandalia M., Pellegrini F., Bailetti D. Joint effect of insulin signaling genes on insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:E1143–E1147. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deepa S.S., Dong L.Q. APPL1: role in adiponectin signaling and beyond. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;296:E22–E36. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90731.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito T., Jones C.C., Huang S., Czech M.P., Pilch P.F. The interaction of Akt with APPL1 is required for insulin-stimulated Glut4 translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:32280–32287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryu J., Galan A.K., Xin X., Dong F., Abdul-Ghani M.A., Zhou L., Wang C., Li C., Holmes B.M., Sloane L.B. APPL1 potentiates insulin sensitivity by facilitating the binding of IRS1/2 to the insulin receptor. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1227–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prudente S., Sesti G., Pandolfi A., Andreozzi F., Consoli A., Trischitta V. The mammalian tribbles homolog TRIB3, glucose homeostasis, and cardiovascular diseases. Endocr. Rev. 2012;33:526–546. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng K.K., Iglesias M.A., Lam K.S., Wang Y., Sweeney G., Zhu W., Vanhoutte P.M., Kraegen E.W., Xu A. APPL1 potentiates insulin-mediated inhibition of hepatic glucose production and alleviates diabetes via Akt activation in mice. Cell Metab. 2009;9:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C., Li X., Mu K., Li L., Wang S., Zhu Y., Zhang M., Ryu J., Xie Z., Shi D. Deficiency of APPL1 in mice impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion through inhibition of pancreatic beta cell mitochondrial function. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1999–2009. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2971-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han W. Dual functions of adaptor protein, phosphotyrosine interaction, PH domain and leucine zipper containing 1 (APPL1) in insulin signaling and insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:8795–8796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206730109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitsuuchi Y., Johnson S.W., Sonoda G., Tanno S., Golemis E.A., Testa J.R. Identification of a chromosome 3p14.3-21.1 gene, APPL, encoding an adaptor molecule that interacts with the oncoprotein-serine/threonine kinase AKT2. Oncogene. 1999;18:4891–4898. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chial H.J., Wu R., Ustach C.V., McPhail L.C., Mobley W.C., Chen Y.Q. Membrane targeting by APPL1 and APPL2: dynamic scaffolds that oligomerize and bind phosphoinositides. Traffic. 2008;9:215–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chial H.J., Lenart P., Chen Y.Q. APPL proteins FRET at the BAR: direct observation of APPL1 and APPL2 BAR domain-mediated interactions on cell membranes using FRET microscopy. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J., Mao X., Dong L.Q., Liu F., Tong L. Crystal structures of the BAR-PH and PTB domains of human APPL1. Structure. 2007;15:525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masuda M., Mochizuki N. Structural characteristics of BAR domain superfamily to sculpt the membrane. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;21:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suetsugu S., Toyooka K., Senju Y. Subcellular membrane curvature mediated by the BAR domain superfamily proteins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;21:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mim C., Unger V.M. Membrane curvature and its generation by BAR proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012;37:526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peter B.J., Kent H.M., Mills I.G., Vallis Y., Butler P.J., Evans P.R., McMahon H.T. BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science. 2004;303:495–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1092586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu T., Shi Z., Baumgart T. Mutations in BIN1 associated with centronuclear myopathy disrupt membrane remodeling by affecting protein density and oligomerization. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e93060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchetti P., Bugliani M., Lupi R., Marselli L., Masini M., Boggi U., Filipponi F., Weir G.C., Eizirik D.L., Cnop M. The endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic beta cells of type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2486–2494. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0816-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.