Abstract

Sessional staff is increasingly involved in teaching at universities, playing a pivotal role in bridging the gap between theory and practice for students, especially in the health professions, including pharmacy. Although sessional staff numbers have increased substantially in recent years, limited attention has been paid to the quality of teaching and learning provided by this group. This review will discuss the training and support of sessional staff, with a focus on Australian universities, including the reasons for and potential benefits of training, and structure and content of training programs. Although sessional staff views these programs as valuable, there is a lack of in-depth evaluations of the outcomes of the programs for sessional staff, students and the university. Quality assurance of such programs is only guaranteed, however, if these evaluations extend to the impact of this training and support on student learning.

Keywords: sessional staff, tutor, training programs, program evaluation, student learning

INTRODUCTION

Since the 1960s, an increasing number of students have attended universities, which has resulted in a worldwide demand for academic staff. Factors such as reduced university funding, increased research demands, changing employment conditions, and a lack of appropriately qualified full-time staff have led to a significant expansion in the number of sessional staff.1-5 In addition to increased reliance on sessional staff, the demand is growing from governments and professional and accrediting bodies for accountability in terms of quality student education. Further pressure has been placed on academia by students, who now make substantial financial contributions to their education and consequently expect value for the money.6-8 Given the increase in workforce casualization and emphasis on appropriate standards of teaching, concerns are being raised over the quality of teaching provided by sessional staff.6,7,9

Following the United States’ lead, countries worldwide are developing programs to address the training and support of sessional staff.7,9-22 Much debate exists, however, about the ideal structure and content of this training, with existing programs varying considerably. Furthermore, as the number of programs continues to increase, there remains limited evidence-based information on the formal assessment or evaluation of such programs.23

SESSIONAL STAFF

The Australian Learning and Teaching Council (ALTC) defines a sessional teacher as “any higher education instructor not in a tenured or permanent position, including part-time tutors or demonstrators, postgraduate students or research fellows involved in part-time teaching, external people from industries or professions, clinical tutors, casually employed lecturers, or any other teachers employed on a course by course basis.”21 The definition of sessional teachers and their functions within the higher education system lack consistency. For the purpose of this review, the term “sessional staff” will include similar or overlapping terms such as tutors, demonstrators, graduate teaching assistants (GTAs), casual academic staff, and teacher practitioners.

Roles and responsibilities of sessional staff vary significantly among institutions and within faculties (schools) and departments. They may include tutoring small groups, demonstrating and teaching in laboratories, teaching clinical skills, leading or facilitating class discussions, grading assignments, giving lectures, setting and grading examinations, and consulting with or supervising students. Due to the increased opportunity for individualized instruction, sessional staff, particularly tutors, plays an important role in creating an environment conducive to learning, which leads to improved student satisfaction and, subsequently, improved student retention rates. They also play a role in student development into professionals.24,25

The profile of the sessional teacher needs to be taken into account when designing teaching and learning development policy.3,26 Traditionally, sessional staff has been recruited from postgraduate students interested in entering academia, with a smaller number being experts from the industry. However, as numbers of sessional staff continue to rise, they are becoming an increasingly diverse group, who vary widely in age, background, qualifications, level of teaching experience, and career aspirations.3,26,27 An estimated 57% of casual academic staff at Australian universities is female, and 52 % are under 35 years old.27 In a survey undertaken at the University of Wellington, New Zealand, involving 72 tutors, Sutherland found that 60% of tutors did not have any form of prior teaching experience.28 Although limited data are available on qualifications of sessional staff, Bexley et al found, in their national survey in Australia involving 622 casual and sessional academics that approximately 77% of these sessional academics had postgraduate qualifications, with 23% at the PhD level, 49% pursuing another degree at the time, and 72% of this group enrolled in a PhD program.29

Sessional staff may be categorized into four groups.3,30,31 “Aspiring academics” are most likely to be young women who are either completing or having recently completed a research higher degree and are interested in a gradual transition from a sessional position to a full-time permanent position in academia/research.3,27 The “industry expert” (teacher-practitioner) is employed in the industry and has a desire to teach future professionals. These teacher-practitioners are frequently employed in vocationally-focused disciplines such as health, law, and engineering. The “career ender” is looking for a gradual progression into retirement. These may be former lecturers or researchers, more commonly male, who are retired or semi-retired, but still wish to contribute to university teaching.3,27 The “freelancer” will often have a number of part-time, casual positions in order to juggle work and family responsibilities.3 These people are more commonly female and are often happy with the flexibility of casual work.27

TRAINING OF SESSIONAL STAFF

Rationale Behind Training

Internationally, half of all teaching in higher education is undertaken by sessional staff.30 Data from the United States indicate that between 1969 and 2011, the number of nontenure track faculty members in higher education rose from 22% to 68% and was comprised of 19% full-time and 49% part-time faculty members. Part-time faculty members experienced more significant growth, and most in this group were exclusively involved in teaching.32 In Australia, tertiary education is regarded as one of the most casualized sectors of education. Data from the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations indicate that in Australia, the proportion of sessional academics (based on full-time equivalent calculations) in that sector rose from 13% in 1989 to 22% in 2007.33 Based on university superannuation data, in terms of actual staff numbers, casual academics are estimated to make up 60% of all academic staff in Australia.27

The significant contribution of sessional staff to the teaching loads at universities has until recently been largely unrecognized and undervalued. These “new” academics are often marginalized, described as “invisible faculty,” with little attention given to their management, support, professional development, and integration into the university teaching team.3,6,9,34 Yet, casual academics play a pivotal role in education delivery, so the lack of attention paid to their training and support is a risk to the quality of teaching and learning in universities.16,35

Using sessional teacher-practitioners in higher education has advantages, particularly in the education of health professionals. Such practitioners assist in bridging the gap between theory and clinical practice by bringing their professional experiences to the classroom, thus guiding students through potential problems and situations that may arise in their profession.30 Sessional staff also play an invaluable role in maintaining currency of the curriculum because they are jointly involved in both the university and the workplace. The accreditation process for professional degree courses requires the development of teaching skills for all academic staff, including sessional staff, be addressed. The Australian Pharmacy Council (APC) encourages the employment of sessional staff such as teacher-practitioners in a pharmacy degree course to “enhance and highlight the nexus between teaching and practice.”8 The APC also requires that all staff contributing to the delivery of the pharmacy program have access to opportunities for developing their teaching and assessment skills.8 This requirement is similar for other professional degrees such as law and medicine.36,37

Given that first-time sessional staff likely have limited or no teaching experience or qualifications, they may require some support and training in their transition to tertiary teaching. Although they may be adequately qualified in their field and possess significant clinical knowledge, sessional staff members are not necessarily equipped with skills and knowledge to effectively teach, manage classes, perform consistent assessment, and deal with special-needs students and challenging student behavior.16,25,30 Sessional staff without training describe their initial experiences as “the sink or swim ethos” or “being tossed into the deep end.”28,31

The overall aim of a sessional staff training program is to improve the quality of teaching and, therefore, the standards of higher education institutions. For the institution, documented potential benefits of sessional staff training include improved student engagement, more effective classroom management, better provision of student feedback, and more effective essay and assignment grading. For sessional staff members themselves, potential benefits include better clarification of roles, responsibilities, and expectations, improved confidence in teaching ability, opportunity to network with other sessional staff, and improved job satisfaction.22,38

For teacher-practitioners (clinicians) in the health professions programs, Halcomb et al stated that while there are many benefits of using clinical experts in a practice-based curriculum, the transition from clinician to educator can be difficult.31 They suggest strategies to improve integration into the particular school or discipline, such as an effective orientation program along with teacher-clinician mentoring, may lead to smoother transition to tertiary teaching and better sharing of knowledge and expertise between faculty members and clinicians. This learning and mentoring partnership can result in improved quality of teaching.31

History of Training Programs

Training GTAs began in the 1960s and is now well established in most Northern American universities, with a wealth of literature available on GTA training, including design of various training programs,17,39-41 development of support materials,23,39,42,43 and evaluations of the effectiveness of such programs.23,40-42,44,45 Lessons learned from the North American experience have been used as the basis for training programs in the United Kingdom (UK), New Zealand, and Australia. In the UK, GTA training programs were often based on well-established New Lecturer Courses, which were modified to address the particular needs of GTAs. Studies investigating specific GTA requirements in the UK led to the development of GTA training programs in institutions such as the University of Bradford, Lancaster University, and the University of London.10-12,14

Tutor training programs were offered at the University of Auckland in New Zealand in the early 1990s; a more formalized, centrally-based tutor training program was established in 1995, which included formal teaching assessment, resulting in the award of a Tutor Training Certificate.6 At the University of Wellington in New Zealand, introductory tutor training was made mandatory because a significant proportion (40%) of part-time limited-term teaching staff were undergraduates. A 2004 sessional staff needs analysis study informed the design and development of this tutor training program.38

The Australian Universities Teaching Committee (AUTC) 2003 Sessional Staff Report was the catalyst for the development of tutor training programs at Australian universities, and this initiative was further encouraged by the release of the ALTC’s RED (Recognition, Enhancement, Development) Report in 2008, which looked at the contribution of sessional teachers to higher education.7,9 Training and development programs for sessional staff exist at many Australian tertiary institutions, including the Universities of Queensland, New South Wales, Sydney, and Melbourne, and the James Cook University in Townsville.1,2,15,20,22,46

Structure and Content of Training Programs

Current sessional staff training programs range from informal meetings at the start of the semester to formal comprehensive semester-long programs. This variation suggests multiple ways to effectively train sessional staff. A program should aim to be relevant to the school’s specific needs and resources and to the requirements of the institution.1 Considering the part-time or casual nature of employment, along with the diversity of sessional staff backgrounds, higher education institutions feel that a practical introductory training session is sufficient and more appropriate than a lengthy theory-based program resulting in a formal qualification.15,23 In Australia, the 2003 AUTC Report provided recommendations for policy guidelines at a university level, as well as policies, processes, and practices at various organizational levels for the most appropriate training, support, and resources for sessional staff. As these are only guidelines, programs need to be tailored to suit the particular institution.

In terms of structure, individual training programs may vary in location and responsibility within the university, format, length and timing, and attendance requirements. Programs may be centrally-based or locally-based, involving the whole university or a specific school or discipline. Often, a 2-tiered or 3-tiered structure exists, with links between the university, department, and individual school or discipline. In a centrally-based program, responsibility often resides with a central teaching and learning department. In a locally-based program, the subject or course coordinator, or a designated sessional staff training coordinator, is the responsible party. Many of the Northern American GTA training programs are taught by full-time professional trainers, often with the assistance of experienced teachers and peer mentors.12 This type of training may range from a half-day, university-wide orientation session to multi-day, university-wide training in conjunction with department-specific training.17 In Australia, training formats include face-to-face workshops, online web-based instruction, tutor training manuals, or combinations of these formats. Face-to-face workshops may be between 2 and 9 hours long and are normally planned to coincide with the commencement of the academic year, although some programs involve regular meetings or contact with tutors throughout the year. Attendance at training programs may be recommended or compulsory and may or may not be subsidized by the institution.

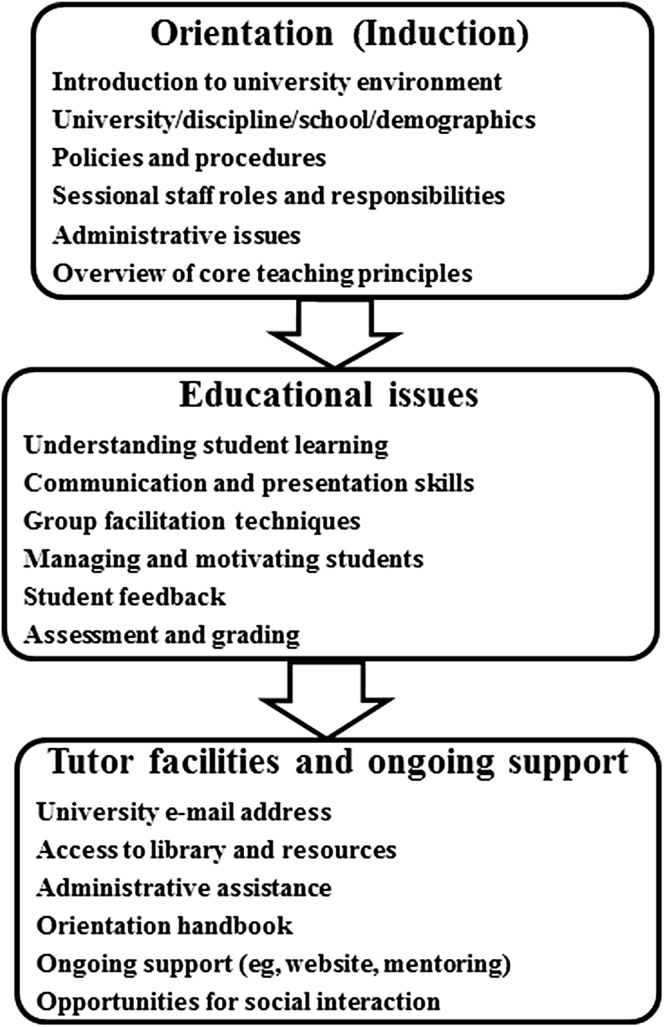

In examining the content of a sessional staff training program, while again varying significantly, the majority of programs include 3 basic areas: orientation, educational issues, and tutor facilities and ongoing support. A summary of a general content framework for a sessional staff training program is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Content Framework for a Sessional Staff Training Program.

Orientation (or induction) generally includes an introduction to the university environment, an overview of the demographics of the particular institution and/or department, relevant teaching and learning policies and procedures, and an outline of sessional staff roles and responsibilities. Information on administrative issues and general teaching principles may also be included. Orientation also gives new staff an opportunity to meet other staff in their discipline, which can help allay initial concerns they may have about their new role.1,15,16 Many universities also provide a school orientation handbook and links to support websites for sessional staff, which may address concerns of sessional teachers.47,48

To compensate for the lack of educational qualifications or experience new tutors may have, basic educational theory is a mandatory component of tutor training programs.38,49,50 While an orientation may provide an overview of teaching principles and practice, a comprehensive tutor training program should include more detailed information and training in the area of teaching and learning. Topics included in current training programs in Australian and New Zealand universities include understanding student learning, communication and presentation skills, techniques for group facilitation, managing and motivating students, student feedback, and assessment procedures.6,48 In North America, GTA training programs are often oriented toward teaching core skills and complemented by more discipline-specific subject training. Furthermore, GTA programs can include practical skills such as academic advising, teaching study skills, dealing with conflict, providing feedback, and effective communicating.12 Techniques for delivery of educational content also vary among programs and include combinations of academic staff presentations, simulation and/or role-play, small group activities, problem solving, and microteaching.

One of the key findings of the 2003 AUTC report was that while induction and orientation programs generally have good standards, there is “a widespread lack of follow-up professional development and support.” Facilities and ongoing support available for sessional staff may include provision of a university e-mail address, access to the library and relevant educational materials, administrative assistance, peer mentoring, and opportunity for social interaction.47,48

EVIDENCE FOR THE BENEFITS OF TRAINING

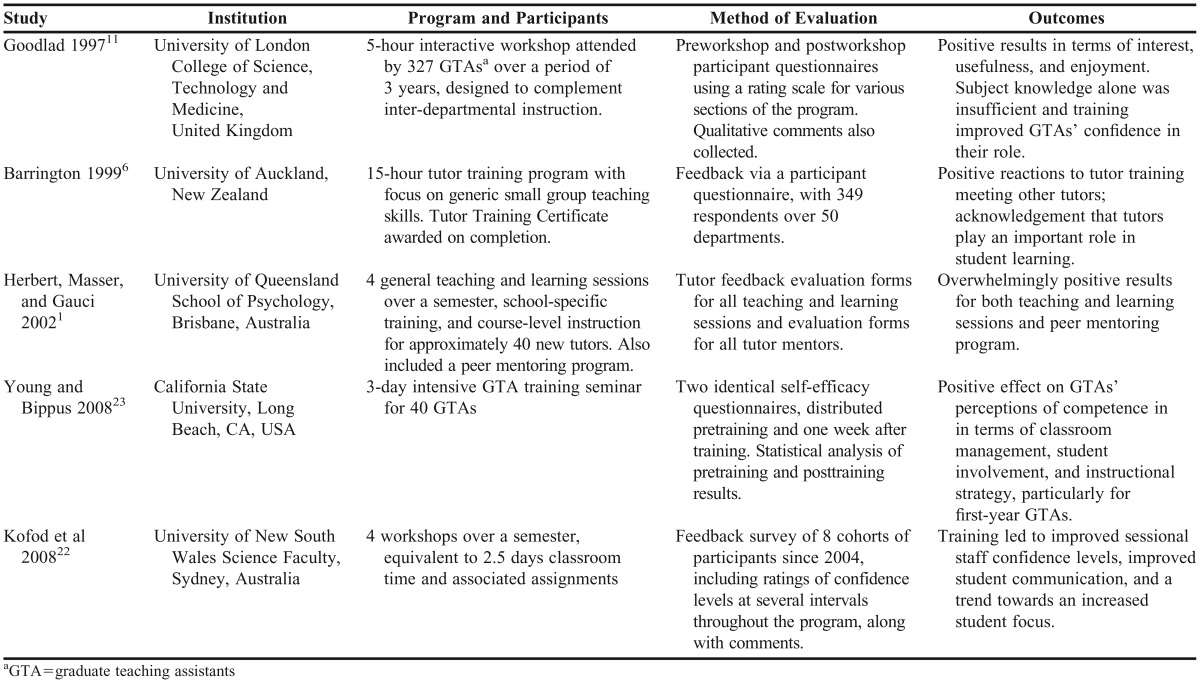

Evidence for benefits of training programs is often anecdotal or, if a posttraining evaluation has been conducted, the results are not comprehensive.17,23 Program evaluations performed in the US, UK, New Zealand, and Australia are conducted in a number of ways, including participant self-evaluation, peer tutor evaluations, student feedback, and classroom evaluations.12,17 Table 1 provides some examples of results from these evaluations.1,6,11,22,23

Table 1.

Samples of Overviews and Outcomes of Sessional Staff Training Programs

In examining the evidence for benefits of sessional staff training programs, one can consider Kirkpatrick’s 4-level model of training criteria as a framework for evaluation of educational effectiveness. This model looks at reaction, learning, behavior, and results, where reaction and learning focus on the training program itself, and behaviour and results focus on changes that occur as a result of the training.51 To date, the majority of evaluation studies examine the effect of training programs on participants (ie, the reaction and learning levels of the Kirkpatrick model). Few studies investigate the effect of the programs on work performance, student engagement, and student outcomes.

The results in Table 1 illustrate that current research supports the benefits of tutor training to improve teaching skills, to enable more effective communication with and management of students, to increase tutor confidence levels, and to improve job satisfaction.1,6,15,16,22,23,28,41,48,52 While results are generally positive in terms of tutor benefits and improved teaching skills, further evidence is required to establish the benefits on student learning and learning outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Sessional staff has evolved from the graduate teaching assistant of the 1960s to a more diverse group including practicing pharmacists, who can help ensure the currency of curricula and relate theory to practice for students. The rapid expansion of sessional staff numbers and associated teaching responsibilities of such staff has implications for the quality of teaching and learning at universities. As a result, universities have been establishing sessional staff training programs. Core elements of a training program exist, but each program should be tailored to suit the needs of its school. Training programs for sessional staff in health professions programs should additionally aim to strengthen the theory-practice link and promote better sharing of knowledge and expertise between full-time faculty members and sessional staff. Improved integration of theory and practice can improve student learning and promote professionalism. The number of sessional staff training programs at universities is increasing worldwide, resulting in improved outcomes in terms of sessional staff job satisfaction, clarification of the role, and increased confidence in teaching ability. However, effects on student learning outcomes remain unexamined. Effectively evaluating sessional staff training and support, especially in terms of student outcomes, will help improve quality teaching and learning at universities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herbert D, Masser B, Gauci P. A comprehensive tutor training program: collaboration between academic developers and teaching staff. Presented at: Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) Symposium 24, Brisbane, Australia. 2002. http://www.aare.edu.au/publications-database.php/3488/A-comprehensive-tutor-training-program:-collaboration-between-academic-developers-and-teaching-staff Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 2.Herbert D, Hannam R, Chalmers D. Enhancing the training, support and management of sessional teaching staff. Presented at: Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) Symposium 26, Brisbane, Australia. 2002. http://www.aare.edu.au/data/publications/2002/her02448.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 3.Kimber M. The tenured ‘core’ and the tenuous ‘periphery’: the casualisation of academic work in Australian universities. J High Educ Policy Manag. 2003;25(1):41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marriott J, Nation R, Roller L, et al. Pharmacy education in the context of Australian practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 131. doi: 10.5688/aj7206131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sosabowski M, Gard R. Pharmacy education in the United Kingdom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 130. doi: 10.5688/aj7206130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrington E. Catching academic staff at the start: professional development for university tutors. Presented at: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA) Conference, Melbourne, Australia. 12–15 July 1999. http://www.herdsa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/conference/1999/pdf/Barring.PDF Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 7.Australian Universities Teaching Committee [AUTC] University of Queensland Teaching and Educational Development Institute. Training, support and management of sessional teaching staff. Final report. 2003. www.olt.gov.au/system/files/resources/sessional-teaching-report.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 8.Australian Pharmacy Council. Accreditation standards for Pharmacy degree programs in Australia and New Zealand. 2014. http://pharmacycouncil.org.au/content/assets/files/Publications/Accreditation%20Standards%20for%20Pharmacy%20Degree%20Programs%202014.pdf Accessed June 7 2015.

- 9.Percy A, Scoufis M, Parry S, Goody A, Hicks M. The RED Report, Recognition - Enhancement -Development: the contribution of sessional teachers to higher education. Australian Learning and Teaching Council [ALTC] 2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1139&context=asdpapers Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 10.Lueddeke G. Training postgraduates for teaching: considerations for programme planning and development. Teach High Educ. 1997;2(2):141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodlad S. Responding to the perceived training needs of graduate teaching assistants. Stud High Educ. 1997;22(1):83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park C. The graduate teaching assistant (GTA): lessons from North American experience. Teach High Educ. 2004;9(3):349–360. [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Andrea V. Arena Symposium: teaching assistants, starting a teaching assistants’ training programme: lessons learned in the USA. J Geogr Higher Educ. 1996;20(1):89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Andrea V. Professional development of teaching assistants in the USA. Report for the Learning and Teaching Support Network. London. 2002. http://www.google.com.au/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CBwQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fjisctechdis.ac.uk%2Fassets%2Fdocuments%2Fresources%2Fdatabase%2Fid116_Professional_Development_of_Teaching_Assistants_in_the_USA.rtf&ei=0x7HU-7cFo2l8AWViIHQCg&usg=AFQjCNHsSOdW-qJnt56sYHx62BVsOwPbew&bvm=bv.71198958,d.dGc Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 15.Stewart C, George A, Peat M. Supporting beginning teachers to support student learning in large first year science classes. Presented at: Sixth Pacific Rim - First Year in Higher Education Conference, Melbourne, Australia. 2004. http://fyhe.com.au/past_papers/papers04.htm Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 16.Kift S. Assuring quality in the casualisation of teaching, learning and assessment: towards best practice for the first year experience. Presented at: 6th Pacific Rim First Year in Higher Education Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand. 2002. http://fyhe.com.au/past_papers/abstracts02/KiftAbstract.htm Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 17.Kurdziel J, Libarkin J. Research methodologies in science education: training graduate teaching assistants to teach. J Geosci Educ. 2003;51(3):347–351. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith C, Bath D. Evaluation of a networked staff development strategy for departmental tutor trainers: benefits, limitations and future directions. Int J Acad Dev. 2003;8(1-2):145–158. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith C, Bath D. Evaluation of a university-wide strategy providing staff development for tutors: effectiveness, relevance and local impact. Mentor Tutor. 2004;12(1):106–122. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston C, Morris G. Off to a good start: sessional tutors development programme. HERDSA News. 2004;26(3):22–25 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/153086709?q&versionId=166839303 Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 21.Australian Learning and Teaching Council [ALTC] Australian Learning and Teaching Council. The RED resource - The contribution of sessional teachers to higher education. 2008. http://www.cadad.edu.au/file.php/1/RED/resource.html Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 22.Kofod M, Quinnell R, Rifkin R. Is tutor training worth it? Acknowledging conflicting agenda. Presented at: Higher Education, Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA) Conference, Rotorua, New Zealand. 1–4 July. 2008. http://www.herdsa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/conference/2008/papers/Kofod.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 23.Young S, Bippus M. Assessment of graduate teaching assistant (GTA) training: a case study of a training program and its impact on GTAs. Commun Teach. 2008;22(4):116–129. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Retna K, Chong E. Cavana, R. Tutors and tutorials: students’ perceptions in a New Zealand university. J High Educ Policy Manag. 2009;31(3):251–260. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan J. The use of practitioners as part-time faculty in postsecondary professional education. Int Educ Stud. 2010;3(4):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cowley J. Confronting the reality of casualisation in Australia. Recognising difference and embracing sessional staff in law schools. Queensland Univ Tech Law Justice J. 2010;10(1):27–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.May R, Strachan G, Broadbent K, et al. The casual approach to university teaching: time for a re-think? Presented at: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA) Conference, Gold Coast, Australia. 4–7 July 2011. http://www.herdsa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/conference/2011/papers/HERDSA_2011_May.PDF Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 28.Sutherland K. Maintaining quality in a diversifying environment: the challenges of support and training for part-time/sessional teaching staff. Presented at: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA) Conference. Perth, Western Australia. 7–10 July 2002. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.126.5616&rep=rep1&type=pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 29.Bexley E, James R, Arkoudis S. The Australian Academic profession in transition; addressing the challenge of reconceptualising academic work and regenerating the academic workforce. Commissioned report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. 2011. http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/people/bexley_docs/The_Academic_Profession_in_Transition_Sept2011.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 30.Andrew S, Halcomb E, Jackson D, et al. Sessional teachers in a BN program: Bridging the divide or widening the gap? Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(5):453–457. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halcomb E, Andrew S, Peters K, Salamonson Y, Jackson D. Casualisation of the teaching workforce: implications for nursing education. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(6):528–532. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kezar A, Maxey D. Student outcomes assessment among the new non-tenure-track faculty majority. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. Occasional paper no. 21. University of Illinois and Indiana University. July 2014. http://learningoutcomesassessment.org/occasionalpapertwentyone.html Accessed September 17, 2014.

- 33.Ryan S, Groen E, McNeil K, et al. Sessional employment and quality in universities: a risky business. Presented at: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA) Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 4–7 July 2011. http://www.herdsa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/conference/2011/papers/HERDSA_2011_Ryan.PDF Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 34.Davis D, Connor R, Perry L, et al. The work of the casual academic teacher: a case study, Employ Relations Rec. 2009;9(2):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Percy A, Beaumont R. The casualisation of teaching and the subject at risk. Stud Contin Educ. 2008;30(2):145–157. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Council of Australian Law Deans (CALD) Standards for Australian Law Schools Final Report. 2009. http://www.cald.asn.au/docs/Roper_Report.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 37.Australian Medical Council. Standards for assessment and accreditation of medical schools by the Australian Medical Council. 2012. http://www.amc.org.au/images/Accreditation/FINAL-Standards-and-Graduate-Outcome-Statements-20-December-2012.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 38.Retna K. Universities as learning organisations: Putting tutors in the picture. Presented at Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA) Conference, Sydney, Australia. 3–6 July 2005. http://www.herdsa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/conference/2005/papers/retna.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 39.Eison J, Vanderford M. Enhancing GTA training in Academic Departments: Some Self-assessment Guidelines, To Improve the Academy: Resources for Faculty, Instructional and Organisational Development. 1993; 12(1): 53–67. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/podimproveacad/277/ Accessed June 19, 2014.

- 40.Rushin J, De Saix J, Lumsden A, STreubel DP, Summers G, Bernson C. Graduate teaching assistant training - A basis for improvement of college biology teaching and faculty development. Am Biol Teach. 1997;59(2):86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savage M, Sharpe T. Demonstrating the need for formal graduate student training in effective teaching practice. Phys Educ. 1998;55(3):130–137. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Condravy J. Learning together: An interactive approach to tutor training. AASCU/ERIC Model Programs Inventory Project Report ED341323, Slippery Rock State College, Pennsylvania. 1990. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED341323. Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 43.Tice S, Gaff J, Pruitt-Logan A. Building on TA development: preparing future faculty programs. Liberal Educ. 1998;84(1):48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mueller A, Penman B, McCann LI, McFadden SH. A faculty perspective on teaching assistant training. Teach Psychol. 1997;24(3):167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shannon D, Twale D, Moore M. TA teaching effectiveness: the impact of training and teaching experience. J High Educ. 1998;69(4):440–464. [Google Scholar]

- 46.James Cook University. Resources – Sessional Teaching Staff. JCU Learning and Teaching, James Cook University, Australia, 2009. http://www.jcu.edu.au/learnandteach/Resources/JCU_121542.html Accessed July 17 2014.

- 47.Baik C. The Melbourne Sessional Teachers’ Handbook – Advice and strategies for small group teaching at the University of Melbourne. 2nd Ed, University of Melbourne, Australia, 2013. http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/prof_dev/new_staff/docs/Sessional_Handbook_2013.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 48.Bath D, Smith C, Steel C. A tutor’s guide to teaching and learning at UQ. Teaching and Educational Development Institute, University of Queensland, Brisbane. 2010. http://www.tedi.uq.edu.au/docs/tutoring/tutor-training-manual.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 49.Prpic J, Ellis A. Influences in the design of a faculty-wide tutor development program. Presented at Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA) Conference, Perth, Australia. 7–10 July 2002. http://www.herdsa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/conference/2002/papers/Prpic.pdf Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 50.Gaia AC, Corts DP, Tatum HE, Allen J. The GTA mentoring program: an interdisciplinary approach to developing future faculty as teacher-scholars. Coll Teach. 2003;51(2):61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Praslova L. Adaptation of Kirkpatrick’s four level model of training criteria to assessment of learning outcomes and program evaluation in higher education. Educ Asse Eval Acc. 2010;22:215–225. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibbs G, Coffey M. (2004) The impact of training of university teachers on their teaching skills, their approach to teaching and the approach to learning of their students. Act Learn High Educ. 2004;5(1):87–100. [Google Scholar]