With HIV becoming a chronic condition, nurses will be providing care to growing numbers of patients aging with this disease. After the introduction of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) in 1996 and 1997, the idea of growing older with this disease has moved from the theoretical to the actual. In fact, HIV is becoming a chronic condition much like diabetes and lupus; all of which are serious life threatening conditions that can also be stabilized with proper adherence to medical treatments. Given this improved prognosis, the age composition of this clinical population has also changed and nurses and allied healthcare professionals are scrambling to know what the clinical characteristics of this emerging population are and what they need to know in order to provide the best evidence-based care for them.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the United States approximately 1.1 million adolescents and adults are infected with HIV.1 In 2005, of those infected, adults 50 years old or older comprised 15% of all new diagnoses, 24% and 29% of individuals living with a diagnosis of HIV and AIDS, respectively, and 35% of AIDS-related deaths.2 This trend is expected to grow as we see more later-life infections and an aging of the general population.

OVERLAP BETWEEN HIV AND AGING

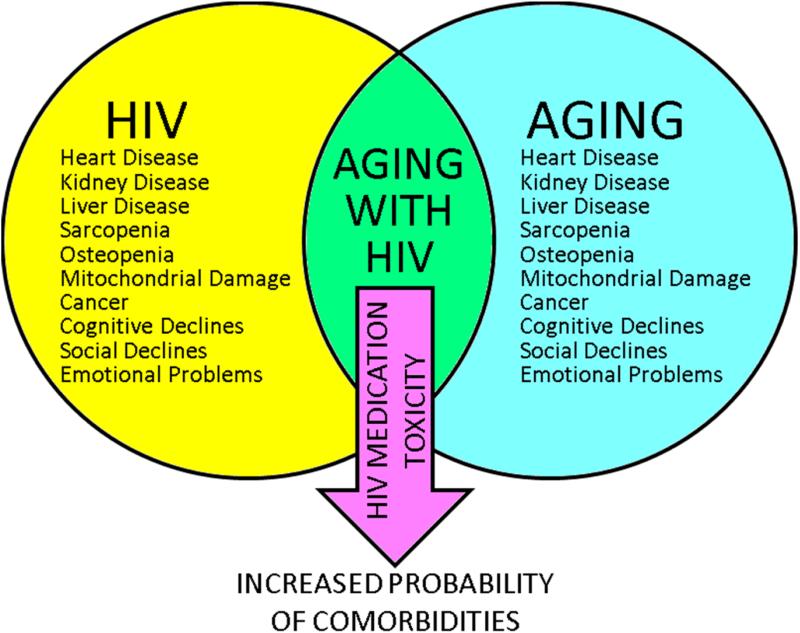

Unfortunately, the literature is just emerging on this topic as researchers and clinicians recognize the need to understand how the processes of aging and HIV interact to impact patient care and well-being. Much of what is known comes from merging the geriatric and HIV literatures and extrapolating possible outcomes. Such outcomes include an increased possibility for comorbidities, cognitive decline, and social isolation; all of which threaten one's ability to age successfully (Figure 1). In a study comparing 2,583 men with HIV under and over 45 years old, older men with HIV exhibited significantly higher rates of weight loss, congestive heart failure, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, neoplasms, pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, nephropathy, and dialysis.3

Figure 1.

The Interaction of Aging, HIV, and Medications on Increased Comorbidities.

Furthermore, the HIV medications which halt the progression of the disease can also be highly toxic. As adults age with HIV, pharmacologic clearance can become less efficient which causes poorer absorption and irregular levels of medication in the body. As a result, medication regimens can be less effective in treating the disease or may result in toxicity. For many individuals, this toxicity can contribute to heart disease, kidney disease, liver disease, cancer, sarcopenia, osteopenia, and mitochondrial damage; conditions that are also prevalent with increased age.4 Emerging studies support that the interactions between HIV, aging, and HIV medications result in elevated risk for these comorbidities in older adults with HIV which can create their own complications.5 Furthermore, the interactions between aging, HIV, HIV medications, other medications, and comorbidities can contribute to cognitive as well as social and emotional problems.

Cognitive Problems

Although the incidence of HIV-related dementia has decreased dramatically with the advent of HAART, studies still indicate that with advancing age, comorbidities, and polypharmacy that those with this disease are experiencing more cognitive declines than their same-aged peers without HIV.6-8 Such cognitive declines may be particularly profound with a history of substance abuse.9 It is important to note that such cognitive declines are often observed by adults with HIV, which can be unsettling and reduce quality of life.10 Such cognitive declines can also affect every day activities such as driving11 and instrumental activities of daily living such as managing finances and adhering to medication schedules.12

Fortunately, studies indicate that older adults with HIV are generally more adherent to their HIV medication schedule.13 This is extremely important since an adherence rate of 95% or higher is recommended to avoid viral mutation and maintaining a healthy immune system.14 However, these same studies show that older adults with HIV who have cognitive problems are less adherent to their HIV medication schedule; this is also seen in the elderly population in general.7,15 By forgetting to take their medications, older adults with memory problems are more prone to experience viral mutation, which can compromise the immune system making HIV more difficult to treat.

It is important to recognize that poor medication adherence can also be caused by medication side effects, cost, and treatment fatigue. Regardless of the reason, poor adherence to medication regimens can lead to viral mutation that produces neurological sequelae and cognitive decline. In turn, such a decline in cognitive functioning can then further exacerbate noncompliance to medication regimens. Thus, a downward spiral of poor adherence and cognitive decline perpetuates each other resulting in reduced quality of life, illness, and perhaps death.

Such cognitive declines are observed in everyday functioning as well. Studies show that older adults with HIV who are experiencing cognitive declines take longer to perform instrumental activities of daily living such as looking up a number in the phone book or counting correct change.16 Obviously, declines in behaviors that promote independence and autonomy compromise one's quality of life. Contributing to such cognitive impairments are social declines and emotional problems such as anxiety or depression. Studies show that such negative emotional affect, which is commonly associated with HIV/AIDS, can also compromise cognitive functioning.17

Social and Emotional Problems

Social withdrawal and isolation due to HIV-related stigma are common. Also, HIV is an expensive disease. Social isolation can be compounded by limited financial resources needed to participate in social activities such as going to the movies, dining out with friends, traveling, and so forth. But in particular, lipodystrophy, a wasting of the subcutaneous fat in the face due to metabolic complications of HAART, can dramatically alter one's appearance, resulting in embarrassment or self-consciousness thus leading to further withdrawal and isolation.18 Shippy and Karpiak, of the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America, surveyed 160 adults with HIV 50 years old or older. They found the majority lived alone (71%) and nearly half (47%) reported being in a committed relationship. The predominant source of social support for these adults was with other older adults with HIV. Although this source of social support would seem to be associated with a type of kinship or camaraderie since they also have lived through similar circumstances surrounding a diagnosis of HIV, many indicated that their emotional needs were not satisfied (57%) and that they were depressed (58%). From this, researchers concluded that older adults with HIV have a fragile social network that may not sustain their needs as they grow older.19

Such a fragile social network, along with the comorbidities that accompany aging with HIV, may overwhelm the internal and external resources of some people, resulting in depression and suicidal ideation. Kalichman and colleagues found that in a sample of 113 older adults with HIV that 27% had thoughts of suicide within the past week.20 This level of suicidal ideation exceeds that of younger adults with HIV. Such emotional problems in older adults with this disease may be exacerbated by factors more severe in this emerging clinical population such as ageism and HIV-related stigma, cognitive declines, comorbidities and failing health, financial distress, and changes in physical appearance due to lipodystrophy. Such suicidal ideation may be expressed in substance use, disregarding medical advice such as adhering to one's medication regimen, or by further social withdrawal.21

SUCCESSFUL AGING WITH HIV

Despite the optimism of being able to age with HIV, the interaction of aging, HIV, and HIV medication toxicity creates a variety of conditions that can compromise one's ability to age successfully. Yet, not everyone will experience these conditions. It is important to remember that these older patients possess individual resources that help them to cope and adjust to the processes of aging with this disease.22 Some people are going to have more cognitive reserve and live a healthier lifestyle which will be protective from experiencing cognitive declines and comorbidities. Others may have more financial resources that help them to sustain social involvement with friends and family while also avoiding the many stressors associated with living from hand to mouth. Still, others may have spiritual resources that help them to weather the challenges of living with these comorbid conditions which gives them meaning in their lives. For example, in a study of 50 adults aging with HIV, 72% of participants indicated that their spirituality changed after being diagnosed with 44% indicating that HIV was a blessing. Of those who considered HIV to be a blessing, they were significantly more likely to use substances less and perceive they were aging successfully.23 Clearly, spirituality represents a powerful resource to reframe one's disease status and improve one's quality of life.

NURSING IMPLICATIONS

This article provides a brief overview of some of the major themes that nurses and allied health professionals will confront as they provide care for older adults with HIV. Being on the frontlines, nurses will see firsthand how some patients will be the very model of successful aging with HIV. These patients will be the ones adhering to their medication regimens and medical appointments, exercising and eating well, being proactive in their physical and mental health, and possessing a sense of meaning and purpose in their lives. In fact, studies show that adults with HIV who are conscientious about their diagnosis fair much better than those who are not.24

By that same token, nurses will also see how many patients will require additional care in lieu of comorbidities such as heart disease, depression, substance use, and social isolation. Being in this position, nurses will be instrumental in not only being advocates for older patients with HIV, but also in helping to define what successful aging will mean and in determining how to achieve it in this emerging population.

As educators, nurses must convey three things to patients with HIV. First, aging with HIV is possible. This point is extremely important, especially for those newly diagnosed fearing that their life is over. Instilling this hope is necessary to motivate patients to take better care of themselves. Second, nurses must explain the necessity of medication adherence and communicate how and why viral mutation occurs and how missing doses increases viral resistance to the HIV medications. Finally, nurses must also relay to patients how to promote general health and wellness (e.g., proper sleep, exercise, stress reduction). Being more physiologically compromised by HIV and advanced age, adults aging with HIV must pay closer attention to lifestyle factors important for maintaining health.

In their clinical practice, nurses must also be aware of not only the increase in comorbidities that can occur as their patients age with HIV, they must also be cognizant of possible cognitive changes and emotional difficulties patients may be experiencing. Cognitive changes can be evaluated through bedside neuropsychological measures such as the Mini-mental State Exam, by noticing changes in behavior and responses to questions, forgetting medical appointments, and by talking with patients’ family members or caregivers.25 Likewise, given the increase of depression and possible suicidal ideation found in this population, changes in mood can also be evaluated through similar techniques such as bedside depression measures and spending time with patients.21 If problems are detected with either cognition or depression, referrals to the appropriate medical professional (e.g., psychologist, neurologist) are warranted.

CONCLUSION

Despite what is known about this emerging clinical population, there is so much that is unknown about aging with HIV. For example, since HIV drug tolerability studies have traditionally excluded older adults, how will HAART affect older adults? What are the contraindications between HIV drugs and those to treat age-related comorbidities? Thus, nurses and allied medical professionals must blend the HIV and gerontological literatures and rely on their clinical judgment to treat this population as the science catches up with the changing demographics of HIV.

For more information on the issues surrounding aging with HIV, readers are recommended to review the following websites (HIV Wisdom for Older Women – www.hivwisdom.org; National Association of HIV Over Fifty – www.HIVoverfifty.org).

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV prevalence estimates – United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(39):1073–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV/AIDS among persons aged 50 and older: CDC HIV/AIDS facts. Washington, DC: 2008. http://www.ced.gov/hiv/topicsover50/factsheets/pdf/over50/pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch K, Morse A. Predictors of survival in older men with AIDS. Geriatr Nurs. 2002;23(2):62–75. doi: 10.1067/mgn.2002.120993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhavan KP, et al. The aging of the HIV epidemic. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:150–8. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greene MD. Older HIV patients face metabolic complications. Nurse Pract. 2003;28(6):17–25. doi: 10.1097/00006205-200306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardy D, Vance D. The neuropsychology of HIV/AIDS in older adults. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19(2):263–72. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinkin CH, et al. Neuropsychiatric aspects of HIV infection among older adults. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:44–52. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00446-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kissel EC, et al. The relationship between age and cognitive function in HIV-infect men. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(2):180–4. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vance DE, Burrage JW., Jr Promoting successful cognitive aging in adults with HIV: strategies for intervention. J Geront Nurs. 2006;32:34–41. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20061101-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vance DE, et al. Self-reported cognitive ability and global cognitive performance in adults with HIV. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40(1):6–13. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200802000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcotte TD, et al. The impact of HIV-related neuropsychological dysfunction on riving behavior. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5:S79–S92. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799577011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heaton RK, et al. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:317–31. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinkin CH, et al. Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance use. AIDS. 2004;18:S19–25. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200418001-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lima VD, et al. The effect of adherence on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality among HIV-infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS. 2007;21(9):1175–83. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuire LC, et al. Cognitive functioning as a predictor of functional disability in later life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):36–42. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192502.10692.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vance DE, et al. Cognitive and everyday functioning in younger and older adults with and without HIV. Clin Gerontol Under Review. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2011.588545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vance DE, et al. The effects of anger on psychomotor performance in adults with HIV: a pilot study. Soc Work Ment Health. 2008;6(3):83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vance DE, Robinson FP. Reconciling successful aging with HIV: a biopsychosocial overview. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2004;3(1):59–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shippy RA, Karpiak SE. The aging HIV/AIDS population: fragile social networks. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(3):246–54. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331336850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalichman SC, et al. Depression and thoughts of suicide among middle-aged and older persons living with HIV-AIDS. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:903–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vance DE, et al. A model of suicidal ideation in adults aging with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19(5):375–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vance DE, et al. Hardiness, successful aging, and HIV: implications for social work. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2008;51(3-4):260–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vance DE. Spirituality of living and aging with HIV: a pilot study. J Relig Spirit Aging. 2006;19(1):57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Cleirigh C, et al. Conscientiousness predicts disease progression (CD4 number and viral load) in people living with HIV. Health Psychol. 2007;26(4):437–80. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vance DE, et al. Assessing the clinical value of cognitive appraisal in adults aging with HIV. J Gerontl Nurs. 2008;34(1):36–41. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]