Abstract

Finger millet (Elucine corocana), locally known as ragi, and probiotics have been recognized for their health benefits. In the present work we describe novel probiotic ragi malt (functional food) that has been prepared using ragi and probiotic Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Lm) and Bacillus subtilis natto (Bs), alone and in combination, for antagonistic activity against Vibrio cholerae (Vc). In vitro studies using pure cultures showed that each probiotic strain (Lm or Bs) was able to inhibit the planktonic growth of Vc as well as its ability to make biofilms and adhere to extracellular matrix proteins (fibronectin, Fn) that may function in vivo as initial ports of entrance of the pathogen. Interestingly, the combination of both probiotic strains (Lm plus Bs) produced the strongest activity against the Vc. When both cultures were used together in the ragi malt the antimicrobial activity against Vc was enhanced due to synergistic effect of both probiotic strains. The inclusion of both probiotic strains in the functional food produced higher amounts of beneficial fatty acids like linoleic and linolenic acid and increased the mineral content (iron and zinc). The viability and activity of Lm and Bs against Vc was further enhanced with the use of adjuvants like ascorbic acid, tryptone, cysteine hydrochloride and casein hydrolysate in the ragi malt. In sum, the intake of probiotic ragi malt supplemented with Lm and Bs may provide nutrition, energy, compounds of therapeutic importance and antagonistic activity against Vc to a large extent to the consumer.

Keywords: Synergistic probiotics, Lactic acid bacteria, Bacillus subtilis, Functional food, Vibrio cholerae

Introduction

The introduction of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria (LAB) has been established in the dairy industry leading to the production of different types of fermented milk and yogurts (Dave and Shah 1998). Although many cereal - based fermented foods are produced indigenously in Asia and Africa by natural lactic acid fermentation, most of them are made under uncontrolled conditions (Oyewole 1997). Therefore, these products exhibit substantial variations in flavor, microbial composition and quality. The viability of LAB in cereals suggest that the utilization of a potential probiotic strain as a starter culture in cereal substrate would produce ragi malt fermented food with defined and consistent characteristics and health -promoting properties.

Probiotic products are usually standardized based on the presumption that culture viability is a measure of probiotic activity. A concentration of log 7 colony forming units (CFU ml-1) at the time of consumption is considered functional (Salminen et al. 1996). The substrate composition and nutritional requirements of the strain considerably affect the overall performance of the fermentation. Microbial growth also depends on the environmental factors like pH, temperature RSEand accumulation of metabolic end products (Kemperman et al. 2010; Sánchez et al. 2010).

It has been found that probiotic is a live microbial dietary adjuvant that beneficially affects the host physiology by modulating mucosal and systemic immunity and improves the nutritional and microbial balance in the intestinal tract. Various methods have been used to improve the growth and survival of these probiotic bacteria during storage by microencapsulation, freeze drying (Chavarri et al. 1988; Carvalho et al. 2004) or using peptides and essential aminoacids (Dave and Shah 1998).

In the present work the development of a novel probiotic functional food has been worked out. The nutritional component of this novel functional food is malted ragi. Ragi (finger millet) is tiny and low priced millet, which has many beneficial properties such as presence of methionine, which is lacking in polished rice, and high amount of calcium, iron, and fiber. In Southern India, ragi is recommended food for infants of age 6 months. Although initially consumed in villages, nowadays due to growing health awareness, people in cities have also started using ragi in their diet. The other part of the developed functional food, the microbial component, is its probiotic content. Our studies have been done to synergistically increase the activity of the functional food against Vc by using two probiotic cultures simultaneously, one of them a traditional LAB Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Lm). In addition to the probiotic lactic strain of Lm, we selected a particular human-friendly strain of the spore-forming probiotic bacterium Bacillus subtilis (Bs) (Senesi 2004; Barák et al. 2005). We selected the Japanese B. subtilis natto strain (Hosoi and Kiuchi 2004) because of its well-known role in the improvement of human health (Barák et al. 2005; Casula and Cutting 2002; Duc et al. 2004). Historically, B. subtilis natto has been consumed since centuries ago as human-friendly probiotic bacterium (Hosoi and Kiuchi 2004; Qiu et al. 2004). B. subtilis natto produces considerable probiotic properties: (i) a positive effect on the proliferation of indigenous probiotic Lactobacillus spp. and Bifidobacterium spp. in the intestine, (ii) induction of a protective cytokine response, (iii) production of proteases with fibrinolytic activity and (iv) isoflavones that seem to have preventive effects against osteoporosis, heart disease and diverse type of cancers (Hosoi and Kiuchi 2004; Nishito et al. 2010; Barák et al. 2005; Casula and Cutting 2002; Duc et al. 2004). In the present work the probiotic properties, in pure cultures and in functional ragi malt, of Bs natto and Lm have been studied against Vibrio cholerae (Vc) as a way to incorporate a new tool available to combat the onset and spread of cholera disease.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and culture conditions

The culture Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Lm) was isolated in the laboratory at CFTRI, India and has been deposited at microbial type culture collection centre (MTCC), Chandigarh, India with an accession no. MTCC 5442 and Bacillus subtilis (Bs) natto RG4365 is obtained from Dr. Akira Nakamura, Tsukuba University, Japan (Arabolaza et al. 2003; Lombardía et al. 2006) and Vibrio cholerae (Vc) was obtained from JSS Medical College, Mysore, India. The cultures Lm and Bs were subcultured in de Mann Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) (Hi Media Pvt. Ltd, India), Luria Bertani yeast extract (LBY, Difco Co, Detroit-USA) - (g l-1) bacto-peptone 10, yeast extract 45, sodium chloride 10 or Luria Bertani (LB, Difco Co, Detroit-USA) broth - (g l-1) bacto-peptone 10, yeast extract 5, sodium chloride 10. To make the respective solid medium 15 g l-1 agar was added.

The culture Vc was handled as per safety norms and according to protocols and rules of the biosecurity and bioethical committees of the institute where work was conducted.

The cultures were subcultured every week and incubated at 37 °C overnight for growth. The cultures were stored at 4 °C between transfers and were subcultured before experimental use. To separate the cell pellet the culture broth was centrifuged at 4,000 g for 30 min. and the broth was decanted. The cell pellet obtained was again centrifuged with saline (0.8 %). The saline was removed and the cell pellet was utilized.

Fluorescein labelling and observation of Vc cells bound to extra cellular matrix (ECM) proteins

Labelling of bacterial cells to study the competitive inhibition of pathogen and binding of probiotic bacteria to immobilized protein by fluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously (Styriak et al. 1999). Briefly, 1 ml of the bacterial culture was adjusted to 9 log CFU ml-1, washed once with pre-warmed PBS (phosphate buffer saline) at 37 °C and re-suspended in 0.8 ml of pre-warmed PBS containing 0.2 ml of freshly prepared fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) solution (1 mg/ml in PBS). After incubation for 45 min at 37 °C bacteria were washed three times (centrifuged) with pre-warmed PBS. The cell pellet was re-suspended in 1 ml of pre-warmed PBS and was used to test bacterial adhesion to the ECM protein fibronectin (FN) immobilized on glass slide. Immobilized bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as control for binding specificity (each protein was used at a final concentration of 1 mg ml-1). Glass slides coated with each particular immobilized protein to be tested were incubated with FITC-labelled Vc bacterial suspension (500 μl; 5 log CFU ml-1) for 1 h at room temperature. Non-adherent cells were removed by gently washing with pre-warmed PBS. Binding of FITC-labelled bacterial cells to each immobilized protein was visualized by fluorescence microscopy and the intensity of the fluorescence signal was interpreted as a measure of the binding capacity of the bacterial cells to bind the fixed ECM protein. Fluorescence microscopy was performed using an IMT-2 inverted microscope (Olympus, Lake Success, NY). Images were acquired with a digital Olympus camera.

Competitive inhibition assays

Vc suspensions from late log phase were FITC-labelled as described above and were mixed with different concentrations of Bs or Lm cells which were grown until late log phase and then applied to Fn coated plates. After incubation of 1 h on an orbital shaker at room temperature, non-bound bacteria were removed by extensive washing with PBS; fluorescence intensity of remaining fixed bacteria was measured in a Beckman Coulter Multimode Detector (DTX 880). In addition, plates were observed in an inverted fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 25 Zeiss, Germany), photographed and registered with an image capture system to observe the inhibition of Vc colonies in presence of Lm alone, Bs alone and in combination.

Microtitre plate assay for V. cholerae biofilm formation

For biofilm (pellicle) formation, overnight Vc cultures were grown till the stationary phase. Different amounts (2–200 μl) of cell-free supernatants obtained after centrifugation from the overnight cultures of Bs or Lm were added to the biofilm growth medium containing the Vc inoculum. All plates were statically incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Biofilm formation was measured using the microtiter plate assay.

Microtiter plate assay

The level of cells adhered to the surface of the microtiter plate wells as a measure of the activity of biofilm-making cells (Hamon and Lazazzera 2001). Vc cells were grown in 96-well polyvinylchloride (PVC) microtiter plates at 37 °C in LBY biofilm medium with or without the supplementation of cell-free supernatants of probiotic bacteria. Cell-free supernatants were prepared by cell separation of overnight cultures of each probiotic strain using 0. 2 μm sterile filters, the supernatants were conserved at 4 °C until used. The bacterial inoculum for the microtiter plates was obtained by growing Vc cells in LBY to mid-exponential phase and then diluting the cells to an OD 600 of 0.08 in biofilm growth medium. Aliquots of 100 μl of the diluted cells were taken in each well of 96-well PVS microtiter plate, including 12 wells with biofilm growth medium alone (negative control). Biofilm formation was evaluated, after overnight incubation of Vc cells in the microtiter plate wells with and without the addition of cell-free supernatant of probiotic strains, by staining with crystal violet (CV). Growth medium and non-adherent cells were carefully removed from the microtiter plate wells. The microtiter plate wells were incubated at 60 °C for 30 min. Biofilms were stained with 300 μl of CV (0.3 % in 30 % methanol) at room temperature for 30 min. Excess of CV was removed and the wells were rinsed with water. The CV that had stained the biofilms was solubilized in 200 μl ethanol (80 % in acetone). Biofilm formation was quantified by measuring the A 570 nm for each well using a Beckman coulter multimode detector (DTX 880). Each data point is an average of 12 wells, and error bars indicate the standard error (p < 0.05). Representative data is an average of three independent experiments.

Preparation of probiotic ragi malt

Finger millet (ragi) was the raw material utilized for the product. This provides dietary fiber as well as nutrients. After cleaning, it was soaked in water with 0.1 % lactic acid for overnight. The next day water was decanted and the soaked grains were kept in a moist cloth, tightly tied and was allowed for malting for 24 h. The ragi malt was ground till smoothness by adding water (1:3). This was heated to 90 °C for 15 min. along with sugar (1/3 rd w/w of millet as the product is a sweetened beverage). This was stirred continuously and then allowed to cool. The product was distributed into conical flasks under aseptic conditions. To the three sets of product (100 ml each) a bacterial inoculum of 2 % was added. One set was inoculated with only Lm, another with only Bs and the third with Lm along with Bs. These were fermented for 24 h at 37 °C and were studied for antagonistic activity against Vc. Increased concentrations of both inoculum (4–12 % of each culture alone and in combination) were also tried to study the effect of inoculum size and synergistic activity to combat Vc.

Growth of VC with probiotic cultures of BS and Lm

The Vc, Lm and BS strains were grown overnight in LBY broth at 37 °C and 150 rpm. The overnight cultures served as starters for the experiments. The initial inoculum taken for Vc was constant (104 CFU ml-1) and it was cultured in the presence of different inoculum sizes of probiotic Bs, Lm and Bs + Lm. Growth and the final cellular yield of each strain were evaluated as CFU ml-1 after overnight incubation in LBY at 37 °C and 150 rpm.

Effect of micronutrient supplementation

To the probiotic ragi malt filter sterilized micronutrients (ascorbic acid, cysteine hydrochloride, casein hydrolysate and tryptone) were supplemented at varying concentrations (100, 250 and 500 mg ml-1) along with the cultures Lm, Bs separately and in combination to enhance the shelf life of the cultures in the product. Viability of the cultures was determined by serial dilution and plating method. An aliquot from the probiotic ragi malt was plated out periodically (after 0, 24, 48, 96 and 144 h) with and without micronutrient supplementation. Agar plates were prepared with MRS medium for Lm and LB agar for Bs. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The colonies grown were counted and expressed as colony forming units (CFU ml-1).

Enhancement of cell viability of cultures as such and in combination in the probiotic product at RT and 4 °C with micronutrient supplementation

Viability of the cultures as determined by serial dilution and plating method. An aliquot from the probiotic ragi malt was plated out periodically (after 0, 24, 48, 96 and 144 h) with and without micronutrient supplementation. Agar plates were prepared with MRS media for Lm and LB agar for Bs. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The colonies grown were counted and expressed as colony forming units (CFU ml-1).

Sensory evaluation

A well trained panel of ten members of food microbiology department, at CFTRI evaluated the product on 5- point hedonic scale for properties like texture, mouth feel, aroma, acidity and overall quality of the product.

Antimicrobial activity assay

Antimicrobial screening was performed by two methods. The agar spot test and well diffusion method as described by Schillinger and Lucke (1989). For plating purpose, 1.5 % agar was added to MRS medium and for overlaying 1.0 % soft agar was used. The pH of the supernatants was adjusted to 6.0 with NaOH. Antimicrobial activity was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution showing definite inhibition of the indicator lawn and is expressed as activity units per milliliter. The inhibitory activity was studied using Vc.

Analytical methods

The bacterial counts were enumerated on selective media. Lm on MRS medium, Bs on LB medium and Vc on BHI medium (Hi Media laboratories). Appropriate dilutions were plated out on respective medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. All experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean ± standard deviations were calculated. The colonies of Bs and Lm are very different and easy to distinguish. The pH and redox of the product were measured directly using a digital pH meter (Genei Pvt. Ltd., India).

Study of other beneficial compounds produced in probiotic ragi malt

Formation of volatile compounds was analyzed at different stages of growth. An aliquot was extracted in dichloromethane (2 g/10 ml) till complete extraction. The filtrate was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate. The sample was concentrated and analysed by GLC with standard library (Shimadzu 14 B). For the GC conditions the column used was SE 30 with injector and detector temp. 250 °C, temperature programming 100 °C (6 min. hold); 100–150 °C at 4 °C/min. and 150–220 °C at 8 °C/min. N2 30 ml/min. For GCMS also the column used was SE-30 under the similar conditions (Agrawal et al. 2000; Shobha and Agrawal 2007).

The cellular fatty acids were extracted by the method of Bligh and Dyer (1959). An aliquot of the product (2 g; wet wt.) was macerated with 3.75 ml of methanol and chloroform in a ratio of 2:1 which was vortexed continuously for 10 min. This was kept at RT for 2 h. The supernatant was collected in a clean dry tube. To this mixture (4.75 ml) methanol, chloroform and water (2:1:0.8) were added and vortexed continuously for 10 min. To the supernatant, chloroform and water (1:1; 2.5 ml) were added. This was vortexed and kept at RT till chloroform layer was separated at the bottom. The chloroform layer was taken in a dried tube and evaporated. To this, hexane (2 ml) was added and kept at RT for 30 min. To each tube methanolic KOH (2 N; 0.1 ml) was added which was kept at RT for 30 min. Hexane layer was removed in a fresh tube and the solvent was evaporated. This was taken in hexane for GC analysis.

Minerals were estimated by standard AOAC method (AOAC international 2007). An aliquot (25 ml) of probiotic ragi malt was tested in a vycor evaporating dish. This was dried at 100 °C overnight in an oven. The dish was placed in a furnace (525 °C) for 5 h. The ash was dissolved in 5 ml (1 N) HNO3 and warmed for 2–3 min. This is taken into a 50 ml volumetric flask which was made up with (1 N) HNO3. Lanthanium chloride solution was added to each standard and test solution to make (0.1 % w/v) for the determination of calcium and magnesium and for sodium and potassium CsCl solution (0.04 M) was added to make 0.5 % (w/v) and was calibrated. Mineral content was calculated as:

|

Lm and Bs cultures alone and together were inoculated (16 h cultures) at 4, 8 and 12 % levels into the malted product. For studying different parameters an aliquot was taken out from each sample after fermentation (24 h at 37 °C).An aliquot from the product was taken every 24 h and was aseptically plated out on MRS medium for Lm and on LB media for Bs (plated after heating at 6 °C). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and the viable count was determined.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean values along with standard deviation are given. All the data from laboratory experiments were analyzed separately for each experiment and were subjected to arcsine transformation and analysis of variance (ANOVA, SPSS, version 16). Significant effects of treatments were determined by the F value (p ≤ 0.05). Treatment means were separated using Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT).

Results and discussion

Inhibition of V. cholerae when co-culturing with Lm and Bs

Bryskier (1998) worked on the antimicrobial activity of Roxithromycin. It displays good activity against pathogens. Champevolier et al. (1993) have studied on the macrolides used in the treatment of cholera in children. The antagonistic activity of bacterial diffusible against V. cholerae compound in the fecal microbiota of rodents was reported (Da Silva et al. 1998). The antibiotic causes certain side effects. Interestingly, the probiotic ragi malt in the present work has shown the synergistic effect of Lm and Bs together with enhanced activity to combat cholera by inhibiting V. cholerae in millet malt with higher amounts of minerals, beneficial fatty acids and volatile compounds with enhanced shelf life of the product and culture viability. The product when consumed may impart therapeutic and nutritional benefits.

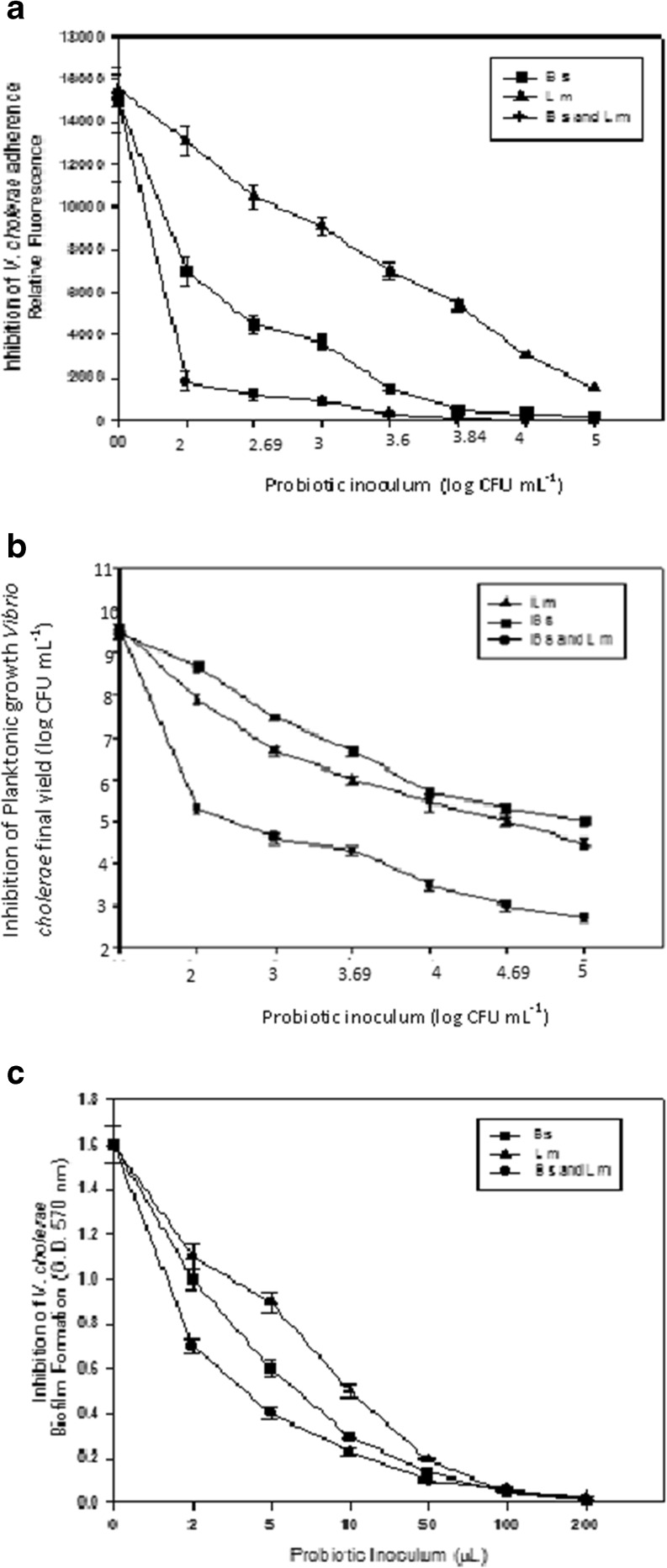

It was observed that each probiotic strain produced a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on the growth of Vc. At the lowest tested dose (1/500 proportion of probiotic to Vc) of either Bs or Lm against Vc (initial inoculum of 102 CFU ml-1 of Bs or Lm and 104 CFU ml-1 of Vc) the final cellular yield of Vc was reduced 5 and 50 times after co-culturing with Bs or Lm respectively. Inhibition of Vc was dose-dependent of the probiotic cultures. Significantly, a combination of both probiotic strains (Bs plus Lm) co-cultured with Vc produced higher inhibitory effect on the growth of the pathogen. The reduction in the growth of Vc cultured in the presence of both probiotic strains (Bs plus Lm; 102 CFU ml-1 each) was 10,000-fold and 1,000,000-folds with 105 CFU ml-1 of Bs and Lm each. It was observed that each probiotic strain, Lm or Bs, is able to produce inhibitory effect on the growth of Vc and had synergistic effect when used in combination (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Inhibition of the planktonic growth of V. cholerae by probiotic B. subtilis and L. mesenteroides. (Black circle) Bs plus Lm, (Black square) Bs and (Black up-pointing triangle) Lm. b Inhibition of V. cholerae binding to ECM proteins by probiotic Bs and Lm (Black circle) Bs plus Lm, (Black square) Bs and (Black up-pointing triangle) Lm. c Inhibition of V. cholerae biofilm formation by cell-free supernatants of probiotic Bs and Lm. (Black circle) Bs plus Lm, (Black square) Bs and (Black up-pointing triangle) Lm

FITC labeling and observation of V. cholerae (Vc) cells bound to ECM proteins

Ability of the probiotic Bs and Lm alone and in combination was studied at different doses blocking the adherence of Vc to fibronectin as a representative protein of the ECM (Fig. 1b). Fluorescent (FITC-labelled) cells of Vc were able to adhere specifically to fibronectin in the absence of competitor probiotic cells. Competitive exclusion of binding of FICT-labelled Vc to Fn in the presence of Bs and Lm cells was found very effective and dose-dependent. At the highest tested doses of the probiotic strains, alone or in combination, the specific binding of Vc to Fn was almost completely blocked since it was observed more than 95 % of reduction of the fluorescence signal derived from Fn -adhered FICT-labelled Vc cells. Therefore, the ability of Vc to compete with Bs or Lm to adhere to Fn was insignificant (Fig. 1c). It has been demonstrated that the presence of specific surface binding sites for extracellular matrix (ECM) components present on several microbial pathogens enable adherence to specific proteins and thereby serve as a mechanism by which infective loci could be established. In particular, the ability to bind to Fn and/or collagen, specifically with high affinity, it is important characteristic to be associated with the virulence of diverse pathogens (Ingham et al. 2004; Schwarz-Linek et al. 2004). In fact, diverse microbial pathogens depend on adhesion to host tissues for initiation of infection. Fn is a 220 kDa glycoprotein that is present at regions of cell-to-cell contact in the gastrointestinal epithelium, thereby providing a potential binding site for pathogens. Numerous bacterial pathogens possess the ability to bind to Fn including Clostridium difficile, Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enteritidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycobacterium avium, Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Vibrio cholerae (Schwarz-Linek et al. 2004) and these binding abilities have been shown to be important for virulence. Thus, if a strategy could be developed to inhibit the early binding of bacterial pathogens to host cells, it would be possible to prevent or combat GI colonization and disease at early steps of infection.

Competitive inhibition of Vc and biofilm formation in the presence of cell-free probiotic supernatants

Bs and Lm were assayed at the lowest dose of 2 μl of cell-free supernatant produced a significant reduction in the ability of Vc to form biofilms (Fig. 1c). At a proportion of 1:1 of Vc cells: cell-free supernatant (1 μl each) negligible biofilm was formed by the pathogens and synergistically cell-free supernatants (Bs or/and Lm) produced no biofilm. Interestingly, this synergistic effect was especially effective at the lowest dose (2 μl of probiotic-derived supernatant) assayed. Svanberg (1995) reported that lactic acid fermentation inhibited the proliferation of Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria including toxicogenic E. coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Shigella flexneri and Salmonella typhimurium. The prevalence of faecal enteric bacteria as Salmonella, Shigella, E.coli in young children was found significantly less in children consuming fermented maize gruel (Nout 1991; Tettech et al. 2004). Antagonistic activity of probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus to inhibit V. cholerae has been studied by Vidya and Iyer (2010). Varghese et al. used the cell free extract of Lb. acidophilus, which inhibited V. alginolyticus in nutrient broth to feed shrimp also they did not find any change in shrimp fed with LAB supplemented diets. Ismail and Soliman (2010) found the cell free extract of Lb. acidophilus inhibited V. vulnificus in nutrient broth. Vaddhakul et al. isolated 327 strains of LAB from 22 types of fermented Thai foods and found isolate PSU-LAB 71 strongly inhibited V. cholerae. Probiotic bacteria may interfere with the growth, biofilm formation and tissue colonization of pathogens through the secretion of extracellular metabolites such as natural antimicrobial, biosurfactants and quorum sensing molecules that would interfere with the intercellular communication of the pathogen (Parsek and Greenberg 2005; Bassler and Losick 2006; Heinzmann et al. 2006; Fujita et al. 2007; Thomas and Versalovic 2010; Sánchez et al. 2010; Fukuda et al. 2011). In our present study the panelists tested each sample and evaluated with the help of the standard score card. The analysis of the results show that, sample labelled as control had thin consistency and gave slight unpleasant raw and fatty aroma. However, the corresponding probiotic product had sourish fermented fruity aroma. Probiotic product shows an overall acceptability score of 4.0 on a scale of 5.0. In a study by Agrawal et al.(2000) idli batter which was prepared from defined microbial cultures the overall quality declined during the 7 days of storage. This did not happen in the present product. The flavor attributes known to be prevalent in the batter arise from the combination of raw materials and the microbial starter cultures used in fermentation.

Cell growth of Lm, Bs and co-culture in probiotic ragi malt

The food industry is orienting towards newer developments in the area of functional foods due to a lot of demand for healthy foods. Probiotic dairy foods containing human derived Lactobacillus sp. and Bifidobacterium sp. and prebiotic food formulations containing ingredients that cannot be digested by the human host in the upper gastro intestinal tract. Cereals and millets offer a very attractive alternative with the multiple beneficial effects. These are used as a fermentable substrate for the growth of probiotic microorganisms. The main parameters to be considered are the processing of the grain, the growth capability and viability of the cultures, the stability of the strain during storage, the organoleptic properties and nutritional value. Additionally, cereals are used as sources of non- digestible carbohydrates that besides promoting several beneficial physiological effects can also selectively stimulate the growth of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria present in the colon and act as prebiotics. Millets contain oligosaccharides and the starch is also known to be used as encapsulation material for probiotics in order to improve their stability during storage and enhance their viability during harsh conditions of the gastro intestinal tract. It is a challenge to the food industry in its effort to utilize the abundant natural resources by producing high quality functional products. In mammals, the mucosal surface area represents an extensive interface with the external environment through which pathogens mainly initiate infections. The lactic acid bacteria of genera Lactobacillus sp., Pediococcus sp., Leuconostoc sp. and Enterococcus sp. were found in fermented maize porridge (Helland et al. 2004). End product distribution of lactic acid fermentation depends on the chemical composition of the substrate and the environmental condition (pH, temperature, aeorbiosis/anaerobiosis). Co-culturing of more than one strain brings out the preferred flavor. It is important that the supporting strains grow in the cereal substrate and do not act antagonistically to each other. The traditional foods made from these grains usually lack flavor and aroma (Chavan et al. 1989). Probiotic potential of spontaneously fermented cereal based foods has been well described (Kalui et al. 2010). The growth of each probiotic strain in the product stored till 96 h was found good with Lm (from 9.6232 log CFU ml-1 to 13.012 log CFU ml-1) and Bs (from 9.6901 log CFU ml-1 to 12.8692 log CFU ml-1) (Tables 1 and 2, respectively). When both the cultures (Lm + Bs) were supplemented equally into the malted ragi it was observed that both the probiotic cultures grew well till 96 h. However, Lm was found to have more viability than Bs (Table 3).

Table 1.

Effect of inoculum concentration of Leuconostoc mesenteroides on its antimicrobial activity and on viability of Vibrio cholerae in probiotic ragi malt

| Inoc. Size (%) | Fermentation period (h) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 24 | 48 | 96 | 144 | ||||||

| Viable count (log Cfu ml-1) | I z (mm) | Viable count Log Cfu ml-1 | I z (mm) | Viable count Log Cfu ml-1 | Iz (mm) | Viable count Log Cfu ml-1 | Iz (mm) | Viable count Log Cfu ml-1 | Iz (mm) | |

| 4 | 9.63 ± 0.01g | 5.0 ± 0.03 | 11 ± 0.63f | 5.2 ± 0.02 | 12.9 ± 0.02b | 5.5 ± 0.04 | 12.9 ± 0.02b | 5.6 ± 0.02 | 12.7 ± 0.01c | 5.0 ± 0.02 |

| 8 | 9.7 ± 0.02g | 5.2 ± 0.01 | 11.8 ± 0.02e | 5.5 ± 0.01 | 12.9 ± 0.03b | 6.2 ± 0.05 | 12.9 ± 0.02b | 6.4 ±0.03 | 12.9 ± 0.03b | 5.5 ± 0.01 |

| 12 | 9.7 ± 0.02g | 5.6 ± 0.02 | 11.9 ± 0.03d | 6.0 ± 0.04 | 13.1 ± 0.03a | 6.8 ± 0.01 | 13 ± 0.01a | 7.5 ±0.01 | 12.9 ± 0.01b | 6.0 ± 0.04 |

| Product control | - | 4.0 ± 0.06 | - | 4.0 ± 0.05 | - | 5.0 ± 0.02 | - | 5.2 ± 0.04 | - | 4.8 ± 0.06 |

Each data is an average of three experiments ± SD (Standard deviation), IZ: Inhibition zone, Values are the mean within the column sharing the same letters are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05)

Table 2.

Effect of inoculum concentration of Bacillus subtilis on its antimicrobial activity and on viability of Vibrio cholerae in probiotic ragi malt

| Inoculum size (%) | Fermentation period (h) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 24 | 48 | 96 | 144 | ||||||

| Viable count Log Cfu ml-1 | Iz(mm) | Viable count Log Cfu ml-1 | Iz(mm) | Viable count Log Cfu ml-1 | Iz(mm) | Viable count log Cfu ml-1 | Iz(mm) | Viable count log Cfu ml-1 | Iz(mm) | |

| 4 | 9.58 ± 0.01i | 4.5 ± 0.02 | 11.5 ± 0.02g | 4.8 ± 0.01 | 12.6 ± 0.01d | 5.1 ± 0.04 | 12.6 ± 0.03d | 6.0 ± 0.03 | 12.6 ± 0.01de | 5.0 ± 0.02 |

| 8 | 9.6 ± 0.01i | 5.0 ± 0.01 | 11.5 ± 0.01g | 5.2 ± 0.02 | 12.6 ± 0.02d | 5.6 ± 0.01 | 12.7 ± 0.02b | 6.3 ± 0.02 | 12.6 ± 0.01c | 5.3 ± 0.01 |

| 12 | 9.7 ± 0.01h | 5.2 ± 0.02 | 11.6 ± 0.02f | 5.5 ± 0.03 | 12.7 ± 0.02b | 6.1 ± 0.05 | 12.8 ±0.02a | 6.5 ± 0.04 | 12.7 ± 0.02b | 6.0 ± 0.03 |

| Product control | - | 4.0 ± 0.01 | - | 4.0 ± 0.04 | - | 5.0 ± 0.06 | - | 5.2 ± 0.02 | - | 4.8 ± 0.04 |

Each data is an average of three experiments ± SD (Standard deviation), IZ:Inhibition Zone

Table 3.

Effect of inoculum concentration of Leuconostoc mesenteroides + Bacillus subtilis on its antimicrobial activity and on viability of Vibrio cholerae in probiotic ragi malt

| Inoculum size (%) | Fermentation period (h) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 24 | 48 | 96 | 144 | |||||||||||

| LM | BS | IZ(mm) | LM | BS | IZ (mm) | LM | BS | IZ (mm) | LM | BS | IZ (mm) | LM | BS | IZ (mm) | |

| 2 + 2 | 7.34 ± 0.02b | 4.07 ± 0.02q | 6.0 ± 0.0 | 6.7 ± 0.03i | 6.5 ± 0.04l | 6.9 ± 0.02 | 6.91 ± 0.04e | 6.8 ± 0.01h | 8.9 ± 0.01 | 7.9 ± 0.01a | 6.8 ± 0.01g | 8.5 ± 0.04 | 6.9 ± 0.02de | 6.8 ± 0.02fg | 8.5 ± 0.01 |

| 4 + 4 | 4.2 ± 0.02o | 4.1 ± 0.01p | 6.8 ± 0.01 | 6.8 ± 0.01e | 6.6 ± 0.01k | 7.3 ± 0.064 | 6 ± 0.01m | 6.9 ± 0.02de | 9.5 ± 0.02 | 7 ± 0.01c | 6.9 ± 0.01de | 9.5 ± 0.06 | 7 ± 0.01c | 6.9 ± 0.01de | 9.5 ± 0.02 |

| 6 + 6 | 4.4 ± 0.02n | 4.4 ± 0.02n | 7.2 ± 0.01 | 6.8 ± 0.02e | 6.6 ± 0.02j | 6.9 ± 0.02 | 7 ± 0.01c | 6.9 ± 0.04de | 8.4 ± 0.04 | 6.9 ± 0.02de | 7 ± 0.02c | 10.0 ± 0.08 | 6.9 ± 0.04de | 6.9 ± 0.03d | 10.0 ± 0.04 |

| Prod. control | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.0 ± 0.06 | NA | NA | 4.2 ± 0.04 | NA | NA | 4.5 ± 0.03 | NA | NA | 4.5 ± 0.03 |

Each data is an average of three experiments ± SD Standard deviation), IZ : Inhibition Zone

Mixed growth of Vc with probiotic Lm and Bs

Maximum inhibition (7.5 mm) using Lm was found after 96 h when 12 % inoculum was added (Table 2). With Bs also similar pattern were observed (Table 3). When both the cultures (Lm + Bs) were supplemented equally to make initial inoculum totally as 4, 8 and 12 % a synergistic effect was found on the antagonistic activity maximum being at 96 h (Table 3).

Culture growth and antimicrobial activity with micronutrients and enhancement of cell viability

Culture viability and antagonistic activity during storage enhanced in the product with ascorbic acid, tryptone, casein hydrolysate and cysteine hydrochloride. Maximum activity was found with tryptone (500 mg/100 ml) both for culture viability and activity against Vc in the probiotic malted ragi product after 144 h (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Effect of different concentrations of adjuvants on cell viability of Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Bacillus subtilis(4 % each)

| 24 h | 48 h | 96 h | 14 4 h | 168 h | 336 h | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conc adjuvant (mg) | LM | BS | LM | BS | LM | BS | LM | BS | LM | BS | LM | BS | |

| 100 | Asc acid | 6.88 ± 0.01efgh | 6.65 ± 0.03pq | 6.85 ± 0.03fghijk | 6.64 ± 0.03q | 6.85 ± 0.03fghijk | 6.71 ± 0.02nop | 6.92 ± 0.02efgh | 6.69 ± 0.02op | 6.98 ± 0.01e | 6.72 ± 0.02nop | 6.94 ± 0.01efg | 6.65 ± 0.02pq |

| Tryptone | 6.84 ± 0.02ghijkl | 6.65 ± 0.02pq | 6.85 ± 0.02fghijk | 6.64 ± 0.02q | 6.91 ± 0.02efgh | 6.70 ± 0.01nop | 6.94 ± 0.02efg | 6.70 ± 0.02nop | 6.94 ± 0.02efg | 6.72 ± 0.03nop | 6.95 ± 0.02ef | 6.85 ± 0.02fghijk | |

| Cas. Hyd | 6.85 ± 0.02fghijk | 6.65 ± 0.02pq | 6.85 ± 0.03fghijk | 6.67 ± 0.02opq | 6.87 ± 0.01 efgh | 6.70 ± 0.01nop | 6.90 ± 0.01efgh | 6.80 ± 0.01lm | 6.93 ± 0.02efgh | 6.05 ± 0.03r | 6.89 ± 0.01efg | 6.76 ± 0.02ijklmn | |

| Cys HCl | 6.85 ± 0.02fghijk | 6.64 ± 0.02q | 6.85 ± 0.03fghijk | 6.71 ± 0.01nop | 6.87 ± 0.02 efgh | 6.71 ± 0.01nop | 6.93 ± 0.01efgh | 6.73 ± 0.02lmnop | 6.96 ± 0.02e | 6.75 ± 0.03jklmnop | 6.86 ± 0.01fghijk | 6.74 ± 0.01klmnop | |

| 250 | Asc acid | 6.85 ± 0.02fghijk | 6.67 ± 0.02opq | 6.87 ± 0.02efgh | 6.71 ± 0.02nop | 6.91 ± 0.02 efgh | 6.74 ± 0.02klmnop | 6.97 ± 0.02e | 6.75 ± 0.02jklmnop | 6.95 ± 0.04ef | 6.73 ± 0.05lmno | 6.93 ± 0.04efgh | 6.76 ± 0.03ijklmn |

| Tryptone | 6.85 ± 0.01fghijk | 6.70 ± 0.02np | 6.84 ± 0.02ghijkl | 6.7 ± 0.03nop | 6.92 ± 0.04 efgh | 6.75 ± 0.01klmnop | 6.95 ± 0.03ef | 6.67 ± 0.02opq | 7.04 ± 0.02e | 6.06 ± 0.03r | 6.95 ± 0.03ef | 6.76 ± 0.03ijklm | |

| Cas. Hyd | 6.86 ± 0.02fghijk | 6.55 ± 0.01r | 6.95 ± 0.04ef | 6.75 ± 0.03klmnop | 6.1 ± 0.1r | 6.75 ± 0.03 klmnop | 7.15 ± 0.03bc | 6.86 ± 0.03fghijk | 7.15 ± 0.05bc | 6.85 ± 0.03fghijk | 7.12 ± 0.02cd | 6.8 ± 0.02ghijkl | |

| Cys HCl | 6.87 ± 0.01efgh | 6.64 ± 0.03q | 6.85 ± 0.03fghijk | 6.7 ± 0.15nop | 6.94 ± 0.04efg | 6.75 ± 0.04 jklmnop | 7.12 ± 0.02bc | 6.83 ± 0.04hijk | 7.16 ± 0.03bcd | 6.85 ± 0.04fghijk | 7.05 ± 0.04d | 6.84 ± 0.03jklmnop | |

| 500 | Asc acid | 6.86 ± 0.02fghijk | 6.70 ± 0.15nop | 6.92 ± 0.03efgh | 6.76 ± 0.03ijklm | 6.75 ± 0.02jklmnop | 7.14 ± 0.03bc bc | 6.84 ± 0.04ghijkl | 6.87 ± 0.02efgh | 7.07 ± 0.03d | 6.82 ± 0.25hijklm | 6.84 ± 0.02ghijkl | 6.75 ± 0.04q |

| Tryptone | 6.84 ± 0.02ghijkl | 6.75 ± 0.04jklmnop | 6.84 ± 0.04ghijkl | 6.74 ± 0.04klmnop | 6.94 ± 0.04efg | 6.75 ± 0.04jjklmnop | 6.94 ± 0.01efg | 6.78 ± 0.01ijklmn | 6.95 ± 0.03ef | 6.73 ± 0.02lmno | 6.86 ± 0.03fghijk | 6.6 ± 0.03efgh | |

| Cas. Hyd | 6.86 ± 0.03fghijk | 6.6 ± 0.07q | 6.84 ± 0.03ghijkl | 6.67 ± 0.0opq | 6.93 ± 0.03efgh | 6.73 ± 0.02lmno | 7.2 ± 0.02b | 6.90 ± 0.04efgh | 7.2 ± 0.03b | 6.89 ± 0.02efgh | 7.12 ± 0.02cd | 6.87 ± 0.03efgh | |

| Cys HCl | 6.9 ± 0.01efgh | 6.65 ± 0.07pq | 7.16 ± 0.02b | 6.84 ± 0.04ghijkl | 7.18 ± 0.04bc | 6.84 ± 0.03ghijkl | 7.31 ± 0.03a | 6.03 ± 0.25r | 7.32 ± 0.03a | 6.97 ± 0.66e | 7.24 ± 0.04ab | 6.93 ± 0.15 | |

Product control – No culture were added. Each data is an average of three experiments ± SD

Table 5.

Effect of Micronutrients on the antimicrobial activity at varying time intervals showing synergistic effect with Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Bacillus subtilis each 4 % initial inoculum

| Adjuvant/(mg ml-1) | Time(h) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 48 | 96 | 14 4 | ||

| 100 | Ascorbic acid | 8.2 ± 0.02 | 8.5 ± 0.03 | 10.2 ± 0.02 | 10.3 ± 0.01 |

| Tryptone | 8.2 ± 0.03 | 8.5 ± 0.03 | 10.5 ± 0.05 | 10.5 ± 0.02 | |

| Casein. hydrolysate | 8.0 ± 0.01 | 8.5 ± 0.05 | 10.5 ± 0.06 | 10.5 ± 0.06 | |

| Cysteine HCl | 8.0 ± 0.04 | 8.5 ± 0.06 | 10.5 ± 0.07 | 10.5 ± 0.03 | |

| 250 | Ascorbic acid | 8.3 ± 0.01 | 9.0 ± 0.08 | 11.0 ± 0.08 | 11.2 ± 0.04 |

| Tryptone | 8.5 ± 0.01 | 9.0 ± 0.04 | 11.0 ± 0.04 | 13.0 ± 0.06 | |

| Casein. hydrolysate | 8.5 ± 0.02 | 10.0 ± 0.06 | 11.4 ± 0.03 | 11.4 ± 0.04 | |

| Cysteine HCl | 8.8 ± 0.02 | 8.8 ± 0.03 | 11.4 ± 0.02 | 11.4 ± 0.06 | |

| 500 | Ascorbic acid | 9.0 ± 0.06 | 10.0 ± 0.06 | 12.0 ± 0.06 | 12.0 ± 0.08 |

| Tryptone | 10.0 ± 0.02 | 10.0 ± 0.08 | 12.2 ± 0.08 | 14.5 ± 0.06 | |

| Casein. hydrolysate | 10.0 ± 0.03 | 11.0 ± 0.02 | 12.0 ± 0.02 | 12.2 ± 0.04 | |

| Cysteine HCl | 8.5 ± 0.04 | 8.6 ± 0.05 | 11.2 ± 0.04 | 12.0 ± 0.02 | |

Product control – No culture were added. Each data is an average of three experiments ± SD

Volatile compound formation, mineral content and fatty acid production

Hexacosane (0.5 %), nonacosane (0.7 %), nonacosanol (2.68 %), nonadecanoic acid (1.32 %) and pentadecanoic acid (1.61 %) were produced in the product without cultures whereas in the probiotic product therapeutically important compounds like propionic acid (2.34 %) and butanoic acid (2.37 %) were produced which have antimicrobial and antiseptic properties (Table 6). Lactic acid fermentation improves the sensorial value which is dependent on the amount of lactic acid and several aromatic volatiles like higher alcohols, aldehydes, esters produced via homofermenative and heterofermentative metabolic pathways. Therefore, appropriate selection of the strain is necessary to efficiently control the distribution of the metabolic end products (Damiani et al. 1996).

Table 6.

Fatty acid profile of ragi malt with or without culture supplementation

| Fatty acids | Ragi malt | Probiotic ragi malt with lm | Probiotic ragi malt with bs | Probiotic ragi malt with lm + bs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caprylic acid (C8) | 0.838 | 1.521 | 0.697 | nil |

| Lauric acid (C12) | 2.824 | 2.454 | 2.258 | nil |

| Myristic acid (C14) | 2.004 | 3.060 | 0.630 | nil |

| Palmitic acid (C16) | 2.053 | 2.544 | 0.848 | 1.718 |

| Stearic acid (C18) | 27.213 | 28.011 | 31.837 | 27.423 |

| Linoleic acid (C18: 2) | 39.969 | 35.268 | 36.816 | 44.301 |

| Linolenic acid (C 18: 3) | 0.898 | 1.899 | 2.168 | 2.086 |

| Arachidonic acid (C20) | 1.972 | - | 1.972 | nil |

Leuconostoc mesenteroides culture alone contained propionic acid (1.3 %) and Butanoic acid (2.0 %); Bacillus subtilis alone contained propionic acid

(1.0 %) and Butanoic acid (0.38 %)

The fatty acids produced were analysed in ragi malt (control), probiotic ragi malt supplemented with Lm, probiotic malted ragi malt with Bs and probiotic malted ragi malt with both the cultures (Lm + Bs).

Ragi malt (control) and with Lm or Bs produced caprylic acid, lauric acid, myristic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid, linoleic acid and linolenic acid, whereas, arachidonic acid was absent. The product with Bs had lower concentration of caprylic acid, myristic acid, palmitic acid and higher concentration of stearic acid, linoleic acid and linolenic acid. The product with both the cultures was high in linoleic and linolenic acids as compared to all other samples (Table 7). The yields of these beneficial medium chain fatty acids were found to increase in the probiotic product as compared to the control. Mineral content (iron and Zinc) were analyzed in product without cultures and in probiotic product supplemented with both the cultures equally to make up 12 % inoculum. Iron increased to 5.3 mg from 5.0 mg/100 mg and zinc increased to 3.0 mg from 2.45 mg/100 g in the product without cultures. Fermentation has been reported to improve the bioavailability of minerals like iron and zinc by reducing phytate compounds present in fermented cereals (Sankara and Deosthala 1983).

Table 7.

Yield of major volatile compounds produced in product as such and with probiotic cultures

| Compounds | Concentration (%) | Fragmentation pattern | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product sample | Probiotic Product culture [LM + BS] | ||

| Hexacosane | 0.50 | 0.50 | 57,71,43,85,99 |

| Nonacosane | 0.71 | nil | 57,43,71,85,99 |

| Nonacosanol | 2.68 | nil | 43,57,97,83,88 |

| Nonadecanoic acid | 1.32 | nil | 43,73,57,29,69 |

| Pentadecanoic acid | 1.61 | nil | 43,60,73,41,55 |

| Propionic acid | nil | 2.34 | 43,55,61,87,98 |

| Butanoic acid | nil | 2.37 | 43,57,69,97,103 |

Sensory evaluation by trained panel members was evaluated on hedonic scale. The overall quality in the sample without cultures got a score of 3.75 whereas the probiotic product got 4.0 out of 5.0. This shows the acceptability of the product Table 8.

Table 8.

Sensory profile of probiotic malted ragi malt and control product

| Physical appearance | Texture | Taste | Overall quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | C | E | C | E | C | E | C |

| 3.75 | 3.75 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.75 | 4.0 | 3.75 |

Sensory attributes (mean scores)

5-Excellent, 4-Very Good, 3- Good, 2- Moderate, 1- Poor

E- Probiotic malted ragi malt product, C-Control

Conclusions

With our work it can be concluded that probiotic LAB can inhibit V. cholerae. However, the synergistic effect of LAB along with Bacillus subtilis in probiotic malted ragi product had enhanced inhibition of Vc, which has not been reported earlier. This will be helpful to the patients suffering with cholera without side effects.

Contributor Information

B. VidyaLaxme, Phone: +91-0821-2517539

A. Rovetto, Phone: +54-341-4353377

R. Grau, Email: robertograu@fulbrightmail.org

Renu Agrawal, Email: renuagrawal46@rediffmail.com.

References

- Agrawal R, Rati ER, Vijayendra SVN, Varadaraj MC, Prasad MS, Krishnanand Flavor profile of idli batter prepared from defined microbial starter cultures. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;16:687–690. doi: 10.1023/A:1008939807778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC (2007) analytical Official methods of analysis. AOAC International 18th ed (985.35 and 968.080 ISBN: 978–0935584783

- Arabolaza A, Nakamura A, Pedrido ME, Martelotto L, Orsaria L, Grau R. Characterization of a novel inhibitory feedback of the anti-anti-sigma factor SpoIIAA on activation of SpooA transcription factor during development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1251–1263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barák I, Ricca E, Cutting S. From fundamental studies of sporulation to applied spore research. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:330–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler BL, Losick R. Bacterially speaking. Cell. 2006;125:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37(911):917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryskier A. Roxithromycin: review of its antimicrobial activity. J Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1998;41(suppl.B):1–21. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AS, Silvaa J, Hob P, Teixeira P, Malcataa FX, Gibbsa P. Relevant factors for the preparation of freeze dried lactic acid bacteria. Int Dairy J. 2004;14:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2004.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casula G, Cutting S. Bacillus probiotics: spore germination in the gastrointestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2344–2352. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2344-2352.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champevolier D, LeNoc P, Bryskier A, Croize J (1993) Comparative in vitro activity of 9 macrolides against 50 Vibrio cholerae strains. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Interscience Conference on antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. New Orleans. LA, American Society for Microbiology. Washington, DC. 231:161

- Chavan UD, Chavan JK, Kadam SS. Effect of fermentation on soluble proteins and in vitro protein digestibility of sorghum, green gram and sorghum green gram blends. J Fd Sci. 1989;53:1574–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1988.tb09329.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chavarri FJ, De Paz M, Nueez MM. Cryoprotective agents for frozen concentrated starters from non- bitter Streptococcus lactis strains. Biotech Lett. 1988;10:11–16. doi: 10.1007/BF01030016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva SH, Vieira EC, Nicoli JR. Antagonism against Vibrio cholerae by bacterial diffusible compound in the fecal microbiota of rodents. Rev Microbiol. 1998;29:3. [Google Scholar]

- Damiani P, Gobbetti M, Cossignanai L, Corsetti A, Simonetti MS, Rossi J. The sourdough microflora characterization of hetero- and homo fermentative lactic acid bacteria, yeasts and their interactions on the basis of the volatile compounds produced. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 1996;29:63–70. doi: 10.1006/fstl.1996.0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dave RI, Shah NP. Ingredient supplementation effects on viability of probiotic bacteria in yoghurt. Dairy Sci. 1998;81:2804–2816. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75839-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duc L, Hong H, Barbosa T, Henriques A, Cutting S. Characterization of Bacillus probiotics available for human use. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:2161–2171. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2161-2171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Musch MW, Nakagawa YHS, Alverdy J, Kohgo Y, Schneewind O, Jabri B, Chang EB. The Bacillus subtilis quorum-sensing molecule CSF contributes to intestinal homeostasis via OCTN2, a host cell membrane transporter. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;4:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Toh H, Hase K, Oshima K, Nakanishi Y, Yoshimura K, Tobe T, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Suzuki T, Taylor TD, Itoh K, Kikuchi J, Morita H, Hattori M, Ohno H. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature. 2011;469:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature09646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon M, Lazazzera B. The sporulation transcription factor SpooA is required for biofilm development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:1199–1209. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzmann S, Entian K, Stein T. Engineering Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 for improved production of the lantibiotic subtilin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;69:532–536. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helland MH, Wicklund T, Narvhus JA. Growth and metabolosim of selected strains of probiotic bacteria in maize porridge with added malted barley. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;91:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi T, Kiuchi K. Production and probiotic effects of natto. In: Ricca E, Henriques AO, Cutting S, editors. Bacterial spore formers: probiotics and emerging applications. Publisher: Horizon Bioscience, UK; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham K, Brew S, Vaz D, Sauder D, McGavin M. Interaction of Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding protein with fibronectin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42945–42953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail MM Soliman WSE (2010) Studies on probiotic effects of lactic acid bacteria against Vibrio vulnificus in freshwater prawn Macrobrachium osenbergii. J Amer Sci 6 (12). Available on line http://www.jofamericanscience.org/journals/am-sci/am0612/

- Kalui CM, Mathara JM, Kutima PM. Probiotic potential of spontaneously fermented cereal based foods. A review. 2010;9:2490–2498. [Google Scholar]

- Kemperman RA, Bolca S, Roger LC, Vaughan EE. Novel approaches for analyzing gut microbes and dietary polyphenols: challenges and opportunities. Microbiology. 2010;156:3224–3231. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.042127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardía E, Rovetto A, Arabolaza A, Grau R. A Lux-S dependent cell to cell language regulates social behavior and development in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4442–4452. doi: 10.1128/JB.00165-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishito Y, Osana Y, Hachiya T, Popendorf K, Toyoda A, Fujiyama A, Itaya M, Sakakibara Y. Whole genome assembly of a natto production strain Bacillus subtilis natto from very short read data. BMC Genomis. 2010;11:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nout MJR. Ecology of accelerated natural lactic acid fermentation of sorghum-based infant food formulas. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;12:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90072-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyewole OB. Lactic fermented foods in Africa and their benefits. Fd Control. 1997;8:289–297. doi: 10.1016/S0956-7135(97)00075-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsek MR, Greenberg EP. Sociomicrobiology: the connections between quorum sensing and biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D, Fujita K, Sakuma Y, Tanka T, Oaci Y, Ohshima H, Tomita M, Itaya M. Comparative analysis of physical maps of tour Bacillus subtilis (natto) genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6247–6256. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6247-6256.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen S, Isolauri E, Salminen E. Clinical uses of probiotics for stabilizing the gut mucosal barrier: successful strains and future challenges. Antonie Van Leewenhock. 1996;70:347–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00395941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez B, Urdaci M, Margolles A. Extracellular proteins secreted by probiotic bacteria as mediators of effects that promote mucosa-bacteria interactyions. Microbiology. 2010;156:3232–3242. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.044057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankara RDS, Deosthala YG. Mineral composition, ionizable iron and soluble zinc in malted grains of pearl millet and ragi. Food Chem. 1983;11:217–223. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(83)90104-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger U, Lucke FK. Antibacterial activity of Lactobacillus sake isolated from meat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55(8):1901–1906. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.8.1901-1906.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz-Linek U, Höök M, Potts J. The molecular basis of fibronectin-mediated bacterial adherence to host cells. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:631–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senesi S. Bacillus spores as probiotic products for human use, chapter 11. In: Ricca E, Henriques AO, Cutting S, editors. Bacterial spore formers: probiotics and emerging applications. Norwich, United Kingdom: Horizon Bioscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shobha PR, Agrawal R. Volatile compounds of therapeutic importance produced by Leuconostoc mesenteroides, a native laboratory isolate. Turk J Biol. 2007;31:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Styriak I, Laukov A, Fallgren C, Wadstrán T. Binding of extracellular matrix proteins by animal strains of Staphylococcal species. Vet Microbiol. 1999;67:99–112. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanberg U. Lactic acid fermented foods for feeding infants. In: Steinkraus KH, editor. Handbook of indigenous fermented foods. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995. pp. 310–347. [Google Scholar]

- Tettech GL, Sefa-Dedeh SK, Phillips RD, Beuchat LR. Survival and growth of acid adapted and unadapted Shigella flexneri in a traditional fermented Ghanian weaning food as affected by fortification with cowpea. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;90:189–195. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Versalovic J. Probiotic-host communication. Modulation of signaling pathways in the intestine. Gut Microbes. 2010;3:148–163. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.11712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidya R, Iyer PR. Antagonistic activity of probiotic organism against Vibrio cholerae and Cryptococcus neoformans. Malaysian J Microbiol. 2010;6:41–46. [Google Scholar]