Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to detect the prevalence of oral H.pylori among adults and to investigate the correlation between H.pylori infection and common oral diseases.

Study design: A cross-sectional study was performed among adults Chinese who took their annual oral healthy examination at The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China.

Results: The study included 1050 subjects in total and oral H.pylori infection occurred in 60.29% of the subjects. The prevalence rates of oral H.pylori in patients with periodontal diseases (63.42%) and caries (66.91%) were significantly increased than those without oral diseases (54.07%), respectively (P < 0.05), while the difference between subjects with recurrent aphthous stomatitis and controls was not significant. In addition, the differences of positive rates of H.pylori with or without history of gastric ulcer were statistically significant (69.47% vs 58.26%, P<0.05). Presenting with periodontal diseases (OR 1.473;95% CI 1.021 to 2.124), caries (OR 1.717; 1.127 to 2.618), and having history of gastric ulcer (OR 1.631; 1.164 to 2.285) increased the risk of H.pylori infection.

Conclusions: Oral H.pylori infection is common in adult Chinese, which is significantly associated with oral diseases including periodontal diseases and caries.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, saliva H.pylori antigen test, caries, periodontal diseases, recurrent aphthous stomatitis

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative and microaerophilic bacterium mainly colonizes the gastric mucosa and also detected in different niches of oral cavity 1,2. Affecting 20-50% of people in industrialized nations and up to 80% of people in less-developed countries 3, H.pylori infection has been a worldwide threat to human health.

Numerous studies have confirmed the promoting role of H.pylori infection in the development of gastritis, peptic ulcers and gastric malignancies 4. Considering oral cavity is a potential extragastric reservoir for H. pylori and may be source of infection, re-infection and transmission 2, researchers also made efforts to explore the association between H.pylori infection and oral diseases. High prevalence of oral H. pylori was detected in patients with periodontitis, poor periodontal health characterized by advanced periodontal pockets, as well as the present of plaque and gingival bleeding 5-7. H. pylori DNA could be found in separate oral mucosal ulcers in apparently immunocompetent adults 8. A retrospective study also suggested that H. pylori-infected children had an increased risk of dental caries 9.

Despite much evidence suggesting the link of H.pylori infection and oral diseases, few studies found no significant correlations between frequencies of H. pylori and dental hygiene, dental caries, periodontal diseases, use of dentures or development of recurrent aphthous stomatitis 10-12.

To date, on the basis of inconsistent findings, whether colonization of H. pylori in the oral cavity is responsible for oral diseases is still controversial. The conflicting results in published works may be due to small subjects population, sample collection and inadequate detection methods for H. pylori infection. We therefore performed a cross-sectional study among 1050 adults Chinese who took their oral healthy examination and used the saliva H.pylori antigen test (HPS) as detection criterion in the purpose of investigating the relationship between H.pylori infection and common oral diseases including periodontal diseases, caries and recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

Materials and Methods

1) Subject population

From March 2013 to June 2013, subjects who took their oral healthy examination at The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China were recruited and selected for this study. Exclusion criteria included age < 18 years; treatment with antibiotics, H2 receptor blockers, bismuth or proton pump inhibitors within four weeks of study enrollment; a past history of oral diseases therapy in the recent 6 months; current pregnancy. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects and the study protocol was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee.

A total of 1050 eligible subjects were enrolled in the study, which consisted of 525 males and 525 females. All the subjects were assessed for oral diseases by dental examination. Diagnosis of oral diseases including periodontal diseases, caries and recurrent aphthous stomatitis were based on the following criteria:

(1) Periodontal diseases: Defined as the presence of two major forms, gingivitis and periodontitis. Individuals with clinical periodontal showing bleeding of gums with probing, deep gum pockets, receding tums which may expose root of tooth, subgingical dental plaque were included 13.

(2) Caries: Defined as different stages of dental caries including caries limited to enamel, caries of dentine and caries of cementum 14. Treated caries without secondary caries were excluded.

(3) Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: The diagnosis was based on clinical findings: history of recurrent oral ulcers beginning in an early age and the presence of multiple round or ovoid oral ulcers on physical exam15. Exclusion criteria including: 1) systemic diseases, Behcet's syndrome and Inflammatory bowel disease, for example. 2) Patients who reported a history of recurrent aphthous stomatitis but in the healing stage were also excluded from the study.

Subjects without finding of oral diseases were selected as the control group.

Information about general conditions, history of gastric ulcer was obtained and samples of saliva were collected for further analysis.

2) The saliva H. pylori antigen test (HPS)

The saliva H. pylori antigen test (Meili Taige Diagnostic Reagent Co., Ltd, Jiaxing, China) is a rapid immunochromatographic assay that uses antibody-coated colloidal gold to detect the presence of flagellin and urease antigens of H. pylori in the saliva specimen 16,17.

No food or drink was allowed 1 h before the test. Subjects were asked to spit at least 0.5 ml saliva to the sampling cup and the collected saliva should be tested within 5 minutes after sampling for reducing the external influence on the results.

To perform the test, we added four drops of saliva and two drops of PBS to the cuvette using a pipette afterward. After mixing adequately, a new pipette was used to transfer four drops of the mixture into the sample well of the test cassette.

The sample flowed through a label pad containing H. pylori antibody coupled to red-colored colloidal gold. If the sample contained H.pylori antigens, the antigen would bind to the antibody coated on the colloidal gold particles to form antigenantibody-gold complexes. The complexes then moved on a nitrocellulose membrane by capillary action toward the test zone. A second control line always appeared in the result window to indicate that the test had been correctly performed and that the test device was functioning properly. The results were observed within 20-30 minutes 17.

The occurrence of two bands in the test and control zones was positive for H. pylori. The faster and deeper appearance of the color ribbon indicating higher content of H. pylori antigen. We could make a more elaborate results determination, strongly positive (red), positive (orange), weakly positive (pink) and very weakly positive (very light pink), according to the color of T-zone ribbon. Then the occurrence of one band in the control zone was negative for H. pylori and if there was no band in the control zone suggested invalid test.

3) Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). The χ 2 test was used to analyze the comparison among groups and calculated OR (Odds Ratio) with 95% CI (Confidence interval). P values less than 0.05 manifested the significance.

Results

1) H.pylori detection and gender, age

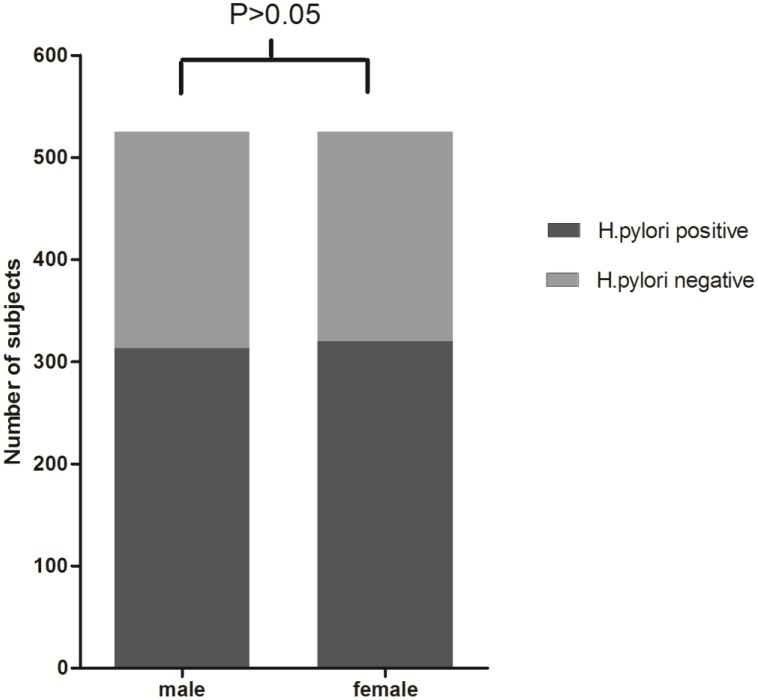

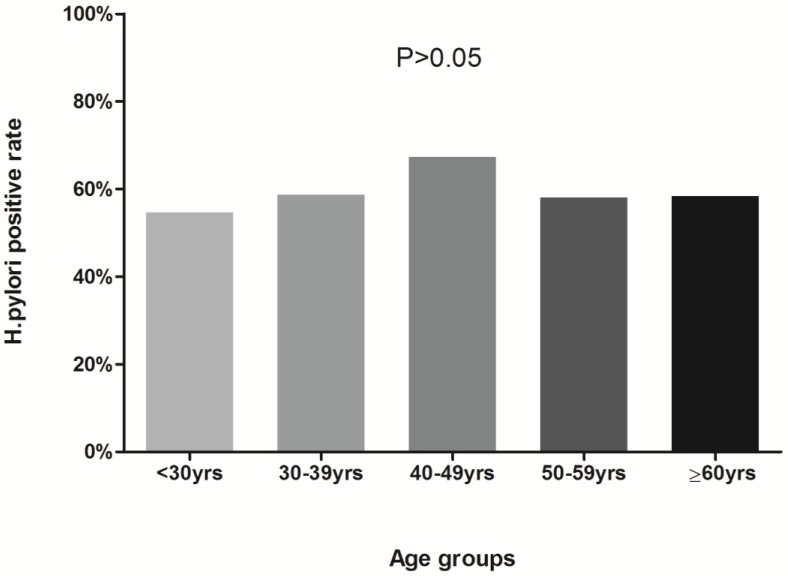

Positive rates of H.pylori detection by HPS from saliva samples for each gender or age groups (<30, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, and 60 or >60 years) were shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Based on HPS, 313 (59.62%) male and 320 (60.95%) female participants were positive for H.pylori. Although female participants showed slight higher positive rates than male, χ2 test suggested that the differences were not statistically significant (χ2=0.195, P>0.05). The presence of H. pylori according to different age groups was as follows: 59 (54.63%) in less than 30 years old group; 178 (58.75%) in subjects between 30 to 39; 181 (67.29%) in subjects between 40 to 49; 156 (57.99%) in subjects between 50 to 59; 59 (58.42%) in 60 or over 60 years old group, and the the differences among groups were not statistically significant(χ2=7.988, ν=4, P>0.05).

Figure 1.

H.pylori antigen test results in male and female. χ2 test showed that the differences of H.pylori positive rates between male and female participants were not statistically significant (59.62% vs. 60.95%, χ2=0.195, P>0.05).

Figure 2.

Percentages of positive H.pylori antigen test in age groups. Participants were divided into less than 30 years old, 30~39 yrs, 40~49 yrs, 50~59 yrs and ≥60 yrs groups. The differences of H.pylori positive rates among groups were not statistically significant (54.63%, 58.75%, 67.29%, 57.99%, 58.42%, respectively; χ2=7.988, ν=4, P>0.05).

2) saliva H.pylori and gastric ulcer

Of 190 saliva samples from participants with a history of gastric ulcer, 132 (69.47%) were positive for H. pylori; while from participants without history of gastric ulcer, 501 (58.26%) were positive. The differences were statistically significant (χ2=8.179, P<0.05). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Results of H.pylori antigen test in subjects with or without a history of gastric ulcer n (%)

| History of gastric ulcer | HPS | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |

| Yes (n=190) | 132(69.47) | 58(30.53) |

| No (n=860) | 501(58.26) | 359(41.74) |

3) saliva H.pylori and oral diseases

The study cohort comprised 1050 adults. Among these eligible subjects, 245 patients had caries and periodontal diseases simultaneously, 606 patients had periodontal diseases without carrying any other oral disease, 30 patients had caries but no any other oral disease, 2 patients had periodontal diseases and recurrent aphthous stomatitis, 8 patients were only diagnosed with recurrent aphthous stomatitis, 24 patients were diagnosed with other oral health problems such as lichen planus, pericoronitis and also glossitis.

Overall, we found 853 (245+606+2) cases of periodontal diseases, 275 (245+30) cases of caries and 10 (2+8) cases of recurrent aphthous stomatitis which presented as minor aphthae localized on labial mucosa (5 patients), tongue (2 patients) and buccal mucosa (3 patients). The rest 135 subjects without finding of any oral diseases were selected as the control group.

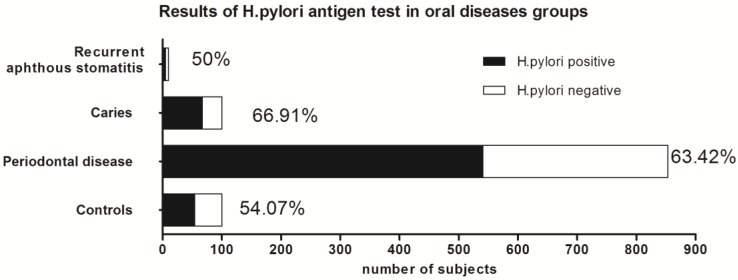

According to saliva specimen results, the prevalence of H. pylori was 63.42% (541 of 853) among patients with periodontal diseases, 66.91% (184 of 275) among patients with caries and 50% (5 of 10) among patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Compared to the H. pylori positive rate among control group (54.07%, 73 of 135), patients with periodontal diseases (χ2=4.331, P<0.05) or caries(χ2=6.377, P<0.05) had significant higher prevalence of H. pylori than control group. However, the difference of H. pylori positive rates between control group and recurrent aphthous stomatitis group was not statistically significant (χ2=0.062, P>0.5). (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Results of H.pylori antigen test in oral diseases groups. Positive rates of H. pylori were 63.42% (541 of 853), 66.91% (184 of 275), 50% (5 of 10) and 54.07% (73 of 135) among subjects with periodontal disease, caries, recurrent aphthous stomatitis and control group, respectively. Patients with periodontal disease and caries had significant higher prevalence of H. pylori than controls (χ2=4.331, P<0.05; χ2=6.377, P<0.05, respectively), while difference between recurrent aphthous stomatitis and control group was not statistically significant (χ2=0.062, P>0.5).

4) factors and risk of H.pylori infection

According to the χ2 test, no significant associations were seen between gender or age and H. pylori infection in the Chinese adults (P>0.05). Oral diseases including periodontal diseases (OR 1.473;95% CI 1.021 to 2.124) and caries (OR 1.717; CI 1.127 to 2.618) were associated with an increased risk of H. pylori infection. However, presenting with recurrent aphthous stomatitis was not a significant risk factor. Moreover, having history of gastric ulcer increased the risk of H.pylori infection in Chinese adults (OR 1.631; 1.164 to 2.285). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Factors and risk of H.pylori infection

| χ2 value | OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||||

| Gender | 0.195 | / | / | 0.659 | |

| age | 7.988 | / | / | 0.095 | |

| Oral diseases | |||||

| periodontal disease | 4.331 | 1.473 | 1.021 to 2.124 | 0.037 | |

| caries | 6.377 | 1.717 | 1.127 to 2.618 | 0.012 | |

| recurrent aphthous stomatitis | 0.062 | / | / | 0.803 | |

| History of gastric ulcer | 8.179 | 1.631 | 1.164 to 2.285 | 0.004 | |

Statistically significant results are shown in bold (p<0.05).

Discussion

In addition to the promoting role of H.pylori infection in the development of gastrointestinal diseases 4, accumulating experimental and clinical evidence has also implicated the association between H.pylori and some diseases localized outside the stomach, such as skin diseases 18,19, gynecological diseases 20, blood system diseases 21,22, cardiovascular diseases 23,24, as well as oral diseases 8,9,25.

Since Krajde 26 isolated H. pylori from dental plaque in 1989, successfully detection of H. pylori from dental plaque, saliva, dorsum of the tongue, surface of oral ulcerations or oral neoplasia strongly suggested that oral-oral route was important transmission modes of H. pylori, and that the oral cavity was a potential extragastric reservoir for H. pylori 2. Despite the works performed by previous researchers trying to answer whether there is an association between H.pylori infection and oral diseases, this question remains unclear.

In the present study, we demonstrated the groups divided by age showed no significant differences in their H.pylori positive rates, which suggested that age were not the influence factors of H.pylori infection. This finding is contrary to the other studies illustrating the prevalence of infection increased with age 27. It could be explained by all the participants we selected were adults and we divided the groups into less than 30 years old, 30~39 yrs, 40~49 yrs, 50~59 yrs and ≥60 yrs, while H.pylori colonization is acquired early in life (almost always before the age of 10 years), and in the absence of antibiotic therapy it generally persists for life 4,28,29.

Our study found the prevalence rates of oral H.pylori in patients with periodontal diseases and caries were significantly increased than control group. These results indicating that saliva H.pylori positive is closely associated with the occurrence and development of oral diseases, which are consistent with the findings in previous studies. Souto et al 5 observed a significantly higher prevalence of H. pylori in the saliva and subgingival samples from subjects with periodontitis (23.5% and 50%, respectively) compared to samples from periodontally healthy subjects (7.3% and 11.4%, respectively; P <0.05). Silva et al 7 observed a positive link between H.pylori infection and periodontal diseases. Dye et al 6 also suggested that poor periodontal health, characterized by advanced periodontal pockets, may be associated with H.pylori infection in adults. An retrospective study conducted in Finland reviewed the public dental health service files of children suggested that H. pylori-infected children have an increased risk of dental caries 9.

Of note, we found no significant differences of rates of oral H.pylori between patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis and controls. However, considering recurrent aphthous stomatitis, Leimola-Virtanen et al 8 suggested association between oral H.pylori infection and oral mucosal ulcers in apparently immunocompetent adults. This divarication may be due to the small sample (n=10) of recurrent aphthous stomatitis patients we enrolled, so the possibility of statistic bias couldn't be ruled out.

Furthermore, considering the strong correlation between H.pylori infection and gastric ulcer, we also analyzed the positive rates of oral H.pylori with or without history of gastric ulcer, and found the differences were statistically significant (69.47% vs 58.26%, P<0.05). This finding is consistent with the results shown by Namiot et al 30 that poor oral health was associated with the prevalence of peptic ulcers not related to NSAIDs consumption. Possible explanations are that oral cavity is an extragastric reservoir of H.pylori and reflects the gastric infection conditions, which is unquestionable the risk factor of gastric ulcer 2,4. Many of the pathogenic strains are shared in dental plaque and gastric mucosa 31. Patients who are oral H.pylori-positive have a lower success rate of gastric H. pylori eradication than patients who test negative for oral H.pylori 2 and both mouthrinse and periodontal treatment can improve the eradication rate of gastric H. pylori 17.

A limitation of this study is that other oral diseases including lichen planus, pericoronitis and glossitis have not been discussed, mainly due to relatively insufficient amount of subjects for further statistical analysis. What's more, given the observation nature of our study, it is not possible to conclude that the positive association between H.pylori in saliva and oral diseases reflects cause and effect. Further studies of large sample size on the involvement of mechanism of H.pylori infection in oral diseases, which may be beneficial to the new prevention and treatment of periodontal disease, caries and even gastric ulcer are needed.

References

- 1.Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:720–741. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou QH, Li RQ. Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity and gastric mucosa: a meta-analysis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1863–1873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souto R, Colombo AP. Detection of Helicobacter pylori by polymerase chain reaction in the subgingival biofilm and saliva of non-dyspeptic periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 2008;79:97–103. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dye BA, Kruszon-Moran D, McQuillan G. The relationship between periodontal disease attributes and Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1809–1815. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva DG, Stevens RH, Macedo JM. et al. Presence of Helicobacter pylori in supragingival dental plaque of individuals with periodontal disease and upper gastric diseases. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:896–901. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leimola-Virtanen R, Happonen RP, Syrjanen S. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Helicobacter pylori (HP) found in oral mucosal ulcers. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:14–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolho KL, Holtta P, Alaluusua S. et al. Dental caries is common in Finnish children infected with Helicobacter pylori. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:815–817. doi: 10.1080/00365540110076624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardo PG, Tugnait A, Hassan F. et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and dental care. Gut. 1995;37:44–46. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berroteran A, Perrone M, Correnti M. et al. Detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in the oral cavity and gastroduodenal system of a Venezuelan population. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:764–770. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-9-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter SR, Barker GR, Scully C. et al. Serum IgG antibodies to Helicobacter pylori in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis and other oral disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen DH, Martin JT. Common dental infections in the primary care setting. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:797–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369:51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scully C. Clinical practice. Aphthous ulceration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:165–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp054630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yee KC, Wei MH, Yee HC. et al. A screening trial of Helicobacter pylori-specific antigen tests in saliva to identify an oral infection. Digestion. 2013;87:163–169. doi: 10.1159/000350432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song HY, Li Y. Can eradication rate of gastric Helicobacter pylori be improved by killing oral Helicobacter pylori? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6645–6650. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakurane M, Shiotani A, Furukawa F. Therapeutic effects of antibacterial treatment for intractable skin diseases in Helicobacter pylori-positive Japanese patients. J Dermatol. 2002;29:23–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akashi R, Ishiguro N, Shimizu S. et al. Clinical study of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori and chronic urticaria and prurigo chronica multiformis: effectiveness of eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori. J Dermatol. 2011;38:761–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golberg D, Szilagyi A, Graves L. Hyperemesis gravidarum and Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:695–703. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000278571.93861.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DuBois S, Kearney DJ. Iron-deficiency anemia and Helicobacter pylori infection: a review of the evidence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:453–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.30252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shuval-Sudai O, Granot E. An association between Helicobacter pylori infection and serum vitamin B12 levels in healthy adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:130–133. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danesh J, Youngman L, Clark S. et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and early onset myocardial infarction: case-control and sibling pairs study. Bmj. 1999;319:1157–1162. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7218.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montenero AS, Mollichelli N, Zumbo F. et al. Helicobacter pylori and atrial fibrillation: a possible pathogenic link. Heart. 2005;91:960–961. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.036681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouziane A, Ahid S, Abouqal R. et al. Effect of periodontal therapy on prevention of gastric Helicobacter pylori recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:1166–1173. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krajden S, Fuksa M, Anderson J. et al. Examination of human stomach biopsies, saliva, and dental plaque for Campylobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1397–1398. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.6.1397-1398.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marie MA. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Large Series of Patients in an Urban Area of Saudi Arabia. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;52:226–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown LM. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:283–297. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perry S, de la Luz Sanchez M, Yang S. et al. Gastroenteritis and transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in households. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1701–1708. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Namiot DB, Namiot Z, Kemona A. et al. Peptic ulcers and oral health status. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:153–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Assumpcao MB, Martins LC, Melo Barbosa HP. et al. Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and stomach of patients from Northern Brazil. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3033–3039. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]