Abstract

Endometrium receptivity is essential for successful embryo implantation in mammals. However, the lack of genetic information remains an obstacle to understanding the mechanisms underlying the development of a receptive endometrium from the pre-receptive phase in dairy goats. In this study, more than 4 billion high-quality reads were generated and de novo assembled into 102,441 unigenes; these unigenes were annotated using published databases. A total of 3,255 unigenes that were differentially expressed (DEGs) between the PE and RE were discovered in this study (P-values < 0.05). In addition, 76,729–77,102 putative SNPs and 12,837 SSRs were discovered in this study. Bioinformatics analysis of the DEGs revealed a number of biological processes and pathways that are potentially involved in the establishment of the RE, notably including the GO terms proteolysis, apoptosis, and cell adhesion and the KEGG pathways Cell cycle and extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interaction. We speculated that ADCY8, VCAN, SPOCK1, THBS1, and THBS2 may play important roles in the development of endometrial receptivity. The de novo assembly provided a good starting point and will serve as a valuable resource for further investigations into endometrium receptivity in dairy goats and future studies on the genomes of goats and other related mammals.

Embryo implantation is a complex initial step in the establishment of successful pregnancy in mammals1 and consists of apposition, adhesion and invasion2. The synchronized differentiation of the receptive endometrium (RE) from the pre-receptive endometrium (PE) is essential for embryo implantation3. The development of endometrial receptivity is known as the “window of implantation” because it is a spatially and temporally restricted stage4. During this period, the endometrium undergoes pronounced structural and functional changes induced by the ovarian steroids oestrogen and progesterone, which prepare it to be receptive to adhesion and subsequent invasion by the embryo5,6. Studies have shown that infertility is partly caused by dysfunction of the receptive endometrium7. Furthermore, impaired uterine receptivity is one of the major reasons for the failure of embryo transplantation in humans and other mammals during assisted reproduction with good-quality embryos8,9.

The development of novel, high-throughput sequencing techniques has provided new strategies that can be used to analyse the functional complexity of the transcriptome10. There are three high throughput sequencing methods that can be used for transcriptomic studies, including the classical 454 pyro-sequencing method and the low-cost Solexa sequencing method; these methods have been employed frequently over the past few years11, but now Illumina sequencing has grabbed that first spot. The RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) approach, which was developed to help analyse global gene expression, is an efficient method to map and quantify the transcriptome12. The holistic view of the transcriptome and its organization provided by the RNA-Seq method has revealed many novel transcribed regions, splice isoforms, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and has allowed the refinement of gene structures13,14,15,16,17. Finally, RNA-Seq generates absolute rather than relative gene expression measurements, thereby providing greater insight and accuracy than do microarrays18,19.

Notably, recent studies have reported that the attainment of endometrial receptivity is a complex process involving numerous molecular mediators4. Molecular studies have extensively investigated the possible genes involved in the establishment of the receptive endometrium20, such as hormones21,22, cytokines23, and growth factors24. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms involved in the development of the endometrium from the pre-receptive state to the receptive state remain largely unknown, and the complexity of the goat transcriptome has not yet been fully elucidated. Drawing on the experience of previous studies, in this study we adopted the Illumina RNA-Seq approach to obtain a larger and more reliable transcriptomic dataset25 from the PE (gestational day 5) and RE (gestational day 15) in dairy goats. Then, we constructed a comprehensive analysis of the endometrial transcriptional profiles at the global level to compare the genes expressed in the PE and RE and further explore DEGs, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and simple sequence repeat (SSR) using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes (KEGG) for DEGs. Therefore, the results of our present study may provide essential information in support of further research on the development of endometrial receptivity in dairy goats. Furthermore, our transcriptomic study will provided good reference data for gene expression profiling of goats.

Results

Sequencing Results

Summary of sequencing

This study used RNA-Seq to compare the transcriptomic landscapes of the endometrium from the PE (gestational day 5) and RE (gestational day 15) phases of 20 healthy, 24-month-old multiparous dairy goats. Total RNA from the receptive and pre-receptive endometria were used to construct RNA libraries for Illumina sequencing. Reads with adapters and low quality reads were removed prior to assembly. In total, we acquired 46,514,662 and 44,185,646 clean reads from the PE and RE libraries, respectively. Approximately 99.86% of the total reads were valid for further analysis (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of the sequencing reads and reads after preprocessing.

| Sample | Raw Reads | Raw Bases | Clean Reads | Clean Bases | Valid Ratio(Reads)% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-receptive endometrium (PE) | 46,582,140 | 465,8214,000 | 46,514,662 | 4,651,466,200 | 99.86% |

| Receptive endometrium (RE) | 44,249,664 | 442,4966,400 | 44,185,646 | 4,418,564,600 | 99.86% |

De novo assembly of sequencing data

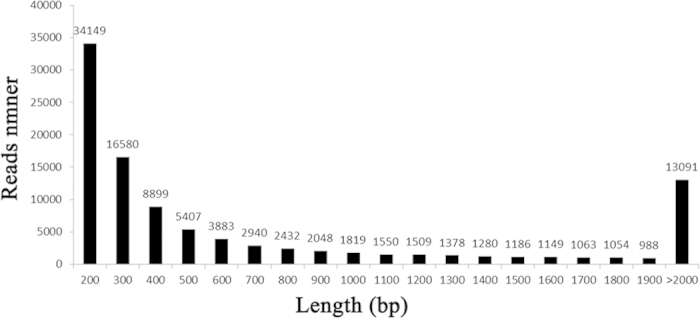

The Trinity software (http://trinityrnaseq.sourceforge.net/) was used for the de novo assembly of our valid reads26. The preprocessed sequencing reads were assembled into 102,441 unigenes using the optimized parameters. The assembled unigenes in the present study were evaluated using the following standard metrics: Min length, Median length, Mean length, N50, Max length, and Total length (Table 2). N50 represents a weighted median statistic such that 50% of the entire assembly is contained in unigenes equal to or larger than this value in base pairs. The mean unigene length was no less than 1,874 bp in this study, while the average length of the unigenes was approximately 896 bp. Thus there were 91,787,136 bases were generated and the sequencing depth was about 98× in this study, what fully guaranteed that the low abundance sequence could be detected. The size distribution of the reads is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 2. Assembly results of unigenes.

| Item | Unigene | Min length | Median length | Mean length | N50 | Max length | Total length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 102,441 | 201 | 404 | 896 | 1,874 | 13,764 | 91,874,680 |

Figure 1. Size distribution of the unigenes.

Unigene Annotation

To exclude interference from alternative splicing of transcripts, first we clustered all of the transcripts that matched the same reference gene; then, we removed redundant transcripts and preserved only the longest transcript from each cluster to represent a unigene27. The unigenes were BLASTed to public database banks including SWISS-PROT (a manually annotated and reviewed protein sequence database), nr (NCBI non-redundant protein sequences), KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), KOG (euKaryotic Ortholog Groups), and Pfam (a widely used protein family and structure domain database). The valid reads were assembled into 102,441 unigenes, (Table S1), of which 36,308 (35%) had BLAST hits to known proteins in SWISS-PROT, 15,220 (14.86%) in nr, 29,835 (29.12%) in Pfam, 34,265 (33.45%) in KEGG, and 37,219 (36.33%) in KOG (Table 3). Because one unigene might be annotated to more than one public database, a total of 43,127 coding genes were found after annotation.

Table 3. Annotation result statistics of unigenes in different databases.

| Databases | SWISS-PROT | NR | Pfam | KEGG | KOG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Unigenes | 36308 | 15220 | 29835 | 34265 | 37219 |

| Percent (%) | 35.44% | 14.86% | 29.12% | 33.45% | 36.33% |

Note: SWISS-PROT, a manually annotated and reviewed protein sequence database.

NR, NCBI non-redundant protein sequences.

Pfam, a widely used protein family and structure domain database.

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

KOG, Karyotic Ortholog Groups.

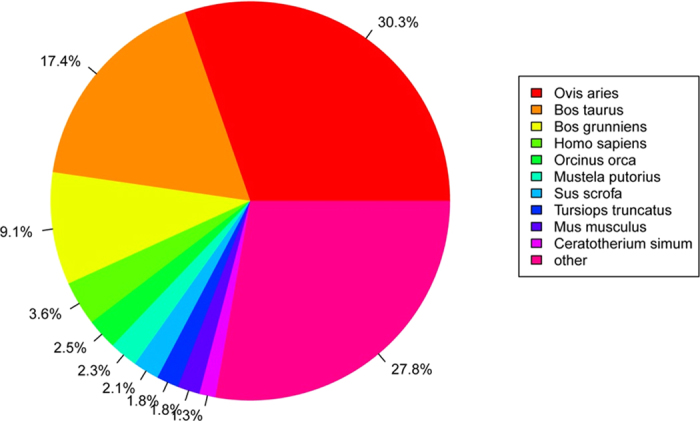

To study the sequence conservation of the endometrium in other animal species, we used BLAST28 to align the unigenes to the NCBI non-redundant database (nr) using an E-value of e−10 as the threshold. A total of 15,220 unique sequences (14.86%) had BLAST hits in the nucleotide sequence database in nr. The majority of the annotated sequences corresponded to known nucleotide sequences of animal species, with 30.3%, 17.4%, 9.1%, 3.6%, and 2.5% matching with Ovis aries, Bos taurus, Bos grunniens, Homo sapiens, and Orcinus sequences, respectively (Fig. 2). KOG (clusters of orthologous groups for eukaryotic complete genomes) is a classification system based on orthologous genes29. In this study, 31,778 unigenes were annotated to 26 groups by the KOG database (Fig. 3). General functional prediction alone (R) annotated 6,009 unigenes at most, and no unigenes were annotated to the Unnamed protein (X). Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning (D) was annotated with 854 unigenes, Extracellular structures (W) was annotated with 113 unigenes.

Figure 2. Species distribution of the BLAST hits.

Figure 3. Histogram of unigene KOG classification.

The x-axis indicates the number of genes annotation under the group, the y-axis indicates 26 groups of KOG.

Detecting SNP and SSR

Next-generation sequencing provides a range of new potential applications for evolutionary and ecological-genetic studies in non-model species30. The discovery of putative SNPs in the RE and PE datasets was summarized. According to the results presented in Table 4, a total of 76,729 putative SNPs were identified for the PE dataset (Table S2), of which 55,044 (71.74%) were transitions and 21,685 (28.26%) were transversions. Similarly, 77,102 putative SNPs were identified from the RE dataset (Table S3), of which 72.13% were transitions and 27.87% were transversions.

Table 4. Result statistics of putative SNPs in pre-receptive and receptive endometrium.

| SNP type | RE library/n | PE library/n |

|---|---|---|

| Transition | 55,044 | 55,611 |

| A-G | 27,339 | 27,783 |

| C-T | 27,705 | 27,828 |

| Transversion | 21,685 | 21,491 |

| A-C | 5,489 | 5,453 |

| A-T | 3,695 | 3,581 |

| C-G | 6,796 | 6,813 |

| G-T | 57,055 | 5,644 |

| Total | 76,729 | 77,102 |

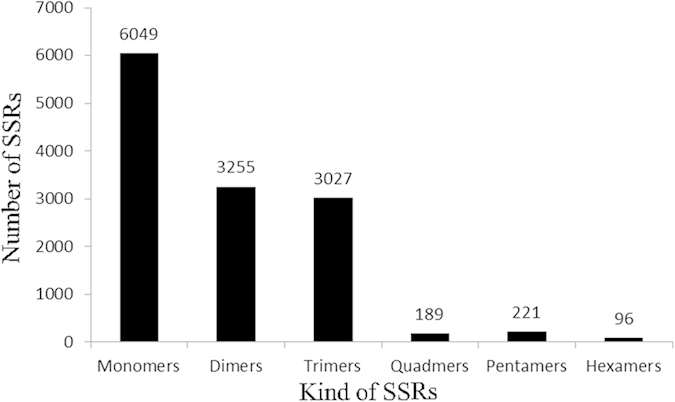

SSRs consist of tandem repeats of short (1–6 bp) nucleotide motifs31 that are distributed throughout the genome32,33. After screening for SSRs in the 102,441 unique sequences using the MISA software, we identified 12,837 SSRs distributed in 10,330 sequences (Table S4). A total of 1,556 sequences contained more than one SSR. Based on the repeat motifs, the SSR loci were divided into monomers (47.12%), dimers (25.36%), trimers (23.58%), quadramers (1.47%), pentamers (1.72%), and hexamers (0.75%) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Histogram of the SSRs in pre-receptive and receptive endometrium.

Differential gene expression and functional characterization

Analysis of Unigene Expression

The RNA-Seq technique allowed the analysis of differential expression profiles via transcript abundance with a high sensitivity for transcripts expressed at low levels34,35. We generated 90 million paired-end reads 100 bp in length, yielding approximately 9 GB of sequence. Thus, the sequencing depth in this study was sufficient to detect transcripts expressed at low levels. To better categorize the unigenes that presented differential expression levels, unigenes expression values RPKM (reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads) were categorized into three groups: high (>500 RPKM), medium (10 to 500 RPKM), and low (<10RPKM) (Table 5). Unigenes that are highly expressed in a specific tissue may be responsible for the basic metabolism and functions of that tissue12. A total of 192 and 187 genes were found to be highly expressed in the PE and RE libraries, respectively.

Table 5. RNA-Seq gene expression results for the RE and PE libraries (RPKM).

| Category | PE | RE |

|---|---|---|

| AHighly expressed genes | 192 | 187 |

| BMedium expressed genes | 7,855 | 8,253 |

| CLowly expressed genes | 89,507 | 87,677 |

| Total expressed genes | 97,544 | 96,177 |

| Unexpressed genes | 4,885 | 6,322 |

Note: RPKM, Reads Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads.

AGene expressional level > 500 RPKM.

BGene expressional level ranging from 10 to 500 RPKM.

CGene expressional level < 10 RPKM.

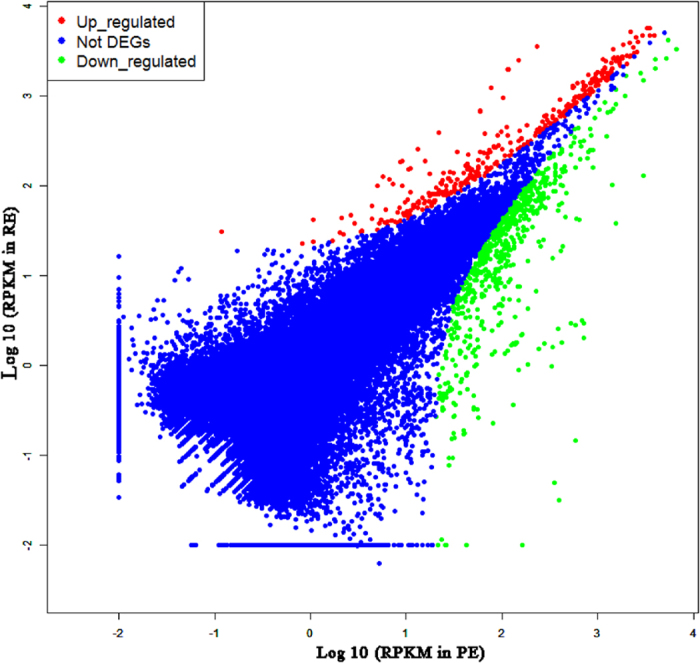

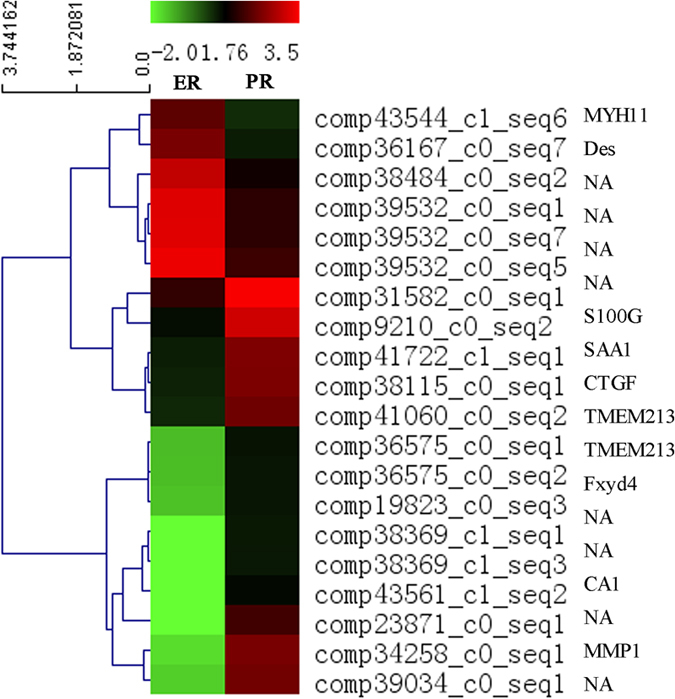

A total of 3,255 unigenes were found to differ significantly in terms of expressional levels (P < 0.05) between the PE and RE libraries; the full list of DEGs is provided in Table S5. There were 208 differentially expressed unigenes that were down-regulated in the RE compared to the PE in goats, while 618 unigenes were up-regulated with fold-changes greater than or equal to 2 (Fig. 5). Additionally, there were 5 unigenes specifically expressed in the receptive endometrium with expression values at the medium level. The top 10 unigenes that were up-regulated in RE compared to PE are shown in Table 6. comp34258_c0_seq1 (MMP1) was the most up-regulated DEG (13.61-fold increase in the RE compared to the PE), followed by comp41692_c0_seq2 (MMP12, 10.89-fold) and comp19823_c0_seq3 (Fxyd4, 8.48-fold). The top 10 down-regulated unigenes are shown in Table 7. The most down-regulated DEG was comp24892_c0_seq2 (NNAT, -5.32-fold increase in the RE compared with the PE), followed by comp43544_c1_seq3 (MYH11, -4.41-fold). A heat map of the Pearson’s correlation and a dendrogram of the correlation between transcript tags are provided in Fig. 6. The up-regulated DEG with the highest level of expression (RPKM = 1525.24) was comp9210_c0_seq2 (S100G) with a 5.34-fold increase in the RE, and the down-regulated DEG with the highest level of expression (RPKM = 1985.32) was comp39532_c0_seq7 (Tes) with a -4.09-fold increase in the RE (Table 8).

Figure 5. Volcano plots analyses of unigenes in PE and RE.

X-axis on both panels shows base 10 logarithm of RPKM of pre-receptive endometrium. Y axis shows receptive endometrium. Red dots indicate up-regulated genes, blue was not DEG, and the green was down-regulated genes in in the receptive endometrium compared to pre-receptive phase.

Table 6. The top 10 unigenes that up-regulated in RE compared with PE.

| ID | Annotated gene | Length | PE (RPKM) | RE (RPKM) | log2 (RE/PE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| comp24368_c0_seq2 | NTS | 1366 | 2.04 | 718.84 | 8.46 | 0 |

| comp39034_c0_seq2 | / | 604 | 0.15 | 582.48 | 11.97 | 0 |

| comp34258_c0_seq1 | MMP1 | 1581 | 0.03 | 396.20 | 13.61 | 1.9126E-88 |

| comp39034_c0_seq1 | / | 505 | 0.05 | 348.97 | 12.78 | 4.14E-78 |

| comp28945_c0_seq2 | / | 331 | 0.98 | 326.77 | 8.38 | 1.1979E-72 |

| comp37557_c0_seq2 | / | 1591 | 0.36 | 129.13 | 8.48 | 8.7967E-30 |

| comp43084_c0_seq85 | ATP6V1C2 | 993 | 0.23 | 79.62 | 8.45 | 5.5951E-19 |

| comp36575_c0_seq1 | TMEM213 | 1063 | 0.09 | 30.22 | 8.33 | 4.2434E-08 |

| comp19823_c0_seq3 | Fxyd4 | 485 | 0.08 | 27.68 | 8.48 | 1.5424E-07 |

| comp41692_c0_seq2 | MMP12 | 2147 | 0.01 | 23.58 | 10.98 | 1.1715E-06 |

Note: Annotated gene displayed that the unigenes had the BLAST hits to known proteins in SWISS-PROT, and “/” meant the unigenes were not blasted to SWISS-PROT. Length represented the bases number of sequence. PE (RPKM) represented the RPKM value (Reads Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads) in the PE library generated from pre-receptive endometrium of Xinong Saanen dairy goats. RE (RPKM) represented the RPKM value in the RE library generated from receptive endometrium of Xinong Saanen dairy goats. log2 (R/P) indicated the fold change between libraries. P-Value manifested the significance of DEG between two samples.

Table 7. The top 10 unigenes that down-regulated in RE compared with PE.

| ID | Annotated gene | Length | PE (RPKM) | RE (RPKM) | log2 (RE/PE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| comp43544_c1_seq6 | MYH11 | 1982 | 255.96 | 13.18 | −4.28 | 2.17E-49 |

| comp43544_c1_seq15 | MYH11 | 6602 | 187.12 | 9.03 | −4.37 | 6.39E-37 |

| comp43544_c1_seq3 | MYH11 | 6620 | 183.74 | 8.62 | −4.41 | 1.99E-36 |

| comp36167_c0_seq5 | / | 1147 | 124.63 | 5.74 | −4.44 | 2.63E-25 |

| comp43563_c1_seq13 | MYH11 | 2176 | 98.86 | 5.05 | −4.29 | 4.04E-20 |

| comp24892_c0_seq2 | Neuronatin | 1298 | 42.31 | 1.06 | −5.32 | 4.01E-10 |

| comp37477_c0_seq1 | PTN | 1710 | 44.25 | 2.10 | −4.39 | 6.42E-10 |

| comp43151_c1_seq1 | / | 859 | 31.17 | 0.12 | −8.04 | 2.98E-08 |

| comp16941_c0_seq1 | / | 201 | 23.79 | 1.08 | −4.47 | 5.43E-06 |

| comp34646_c0_seq1 | / | 1933 | 22.85 | 0.82 | −4.80 | 6.20E-06 |

Note: Annotated gene displayed that the unigenes had the BLAST hits to known proteins in SWISS-PROT, and “/” meant the unigenes were not blasted to SWISS-PROT. Length represented the bases number of sequence. PE (RPKM) represented the RPKM value (Reads Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads) in the PE library generated from pre-receptive endometrium of Xinong Saanen dairy goats. RE (RPKM) represented the RPKM value in the RE library generated from receptive endometrium of Xinong Saanen dairy goats. log2 (R/P) indicated the fold change between libraries. P-Value manifested the significance of DEG between two samples.

Figure 6. Clustering analysis of differentially expressed unigenes.

Heat map of Pearsons correlation across the 20 most differentially expressed transcript tags, and a dendrogram of correlation between transcript tags is shown to the left of the heatmap.

Table 8. DEG with highly expressed level in R or PE libraries (|log2 (RE/PE)|>2).

| ID | Annotated gene | Length | PE (RPKM) | RE (RPKM) | log2 (RE/PE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| comp25223_c0_seq1 | / | 841 | 3492.60 | 230.13 | −3.92 | 0.00 |

| comp42940_c0_seq4 | / | 3052 | 671.00 | 59.12 | −3.50 | 0.00 |

| comp39532_c0_seq1 | Tes | 1456 | 1958.36 | 115.02 | −4.09 | 0.00 |

| comp39532_c0_seq7 | Tes | 1701 | 1985.32 | 116.82 | −4.09 | 0.00 |

| comp42901_c0_seq4 | IGFBP3 | 4158 | 951.25 | 102.93 | −3.21 | 0.00 |

| comp38484_c0_seq2 | / | 1744 | 1241.57 | 76.95 | −4.01 | 0.00 |

| comp39532_c0_seq5 | / | 1014 | 2487.73 | 149.24 | −4.06 | 0.00 |

| comp42940_c0_seq3 | / | 3023 | 676.00 | 59.41 | −3.51 | 0.00 |

| comp24368_c0_seq2 | NTS | 1366 | 2.04 | 718.84 | 8.46 | 0.00 |

| comp29997_c0_seq1 | COL1A2 | 5188 | 42.26 | 634.41 | 3.91 | 0.00 |

| comp42978_c0_seq2 | COL3A1 | 5664 | 159.37 | 884.09 | 2.47 | 0.00 |

| comp25409_c0_seq1 | PLA2G10 | 812 | 3.13 | 687.16 | 7.78 | 0.00 |

| comp30511_c0_seq1 | / | 1189 | 42.98 | 594.48 | 3.79 | 0.00 |

| comp9210_c0_seq2 | S100G | 495 | 37.68 | 1525.24 | 5.34 | 0.00 |

| comp36285_c0_seq1 | / | 1302 | 101.33 | 1400.23 | 3.79 | 0.00 |

| comp39911_c0_seq1 | S100G | 1060 | 2.98 | 709.07 | 7.90 | 0.00 |

| comp39034_c0_seq2 | / | 604 | 0.15 | 582.48 | 11.97 | 0.00 |

| comp39911_c0_seq8 | S100G | 1150 | 2.84 | 579.32 | 7.67 | 0.00 |

| comp25409_c0_seq5 | PLA2G10 | 902 | 2.94 | 523.92 | 7.48 | 0.00 |

| comp31582_c0_seq1 | / | 2192 | 128.19 | 2994.99 | 4.55 | 0.00 |

| comp23871_c0_seq1 | / | 1179 | 0 | 163.62 | Inf | 1.39E-37 |

| comp43561_c1_seq2 | CA1 | 2100 | 0 | 42.20 | Inf | 7.67E-11 |

| comp38369_c1_seq3 | / | 563 | 0 | 25.83 | Inf | 3.57E-07 |

| comp38369_c1_seq1 | / | 457 | 0 | 25.28 | Inf | 4.74E-07 |

| comp38369_c1_seq5 | / | 680 | 0 | 21.24 | Inf | 3.92E-06 |

Note: Annotated gene displayed that the unigenes had the BLAST hits to known proteins in SWISS-PROT, and “/” meant the unigenes were not blasted to SWISS-PROT. Length represented the bases number of sequence. PE (RPKM) represented the RPKM value (Reads Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads) in the PE library generated from pre-receptive endometrium of Xinong Saanen dairy goats. RE (RPKM) represented the RPKM value in the RE library generated from receptive endometrium of Xinong Saanen dairy goats. log2 (R/P) indicated the fold change between libraries. P-Value manifested the significance of DEG between two samples.

Gene Ontology Analysis of the DEGs

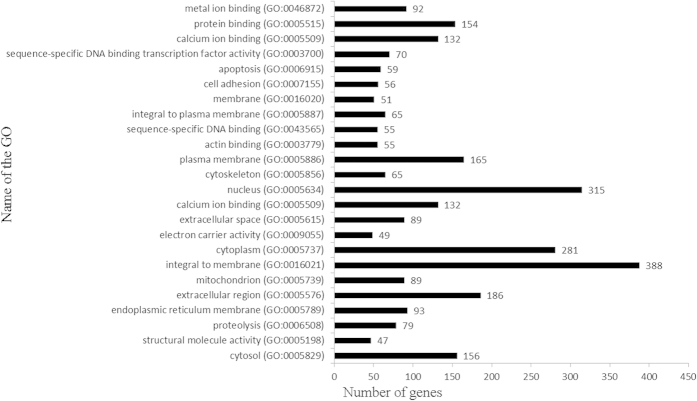

The DEGs were analysed by running queries for each DEG against the GO database, which provides information related to three ontologies: molecular function, cellular component, and biological process. In this study, GO enrichments of the DEGs were categorized into 426 functional groups that met the criteria of P-values < 0.001. Out of the 133 terms that were significantly enriched in molecular functions (Table S6), the most significantly enriched GO terms were protein binding (GO: 0005515) with 154 genes annotated, followed by ATP binding (GO: 0005524), calcium ion binding (GO: 0005509), metal ion binding (GO: 0046872), and sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity (GO: 0003700). In the cellular compartment GO category, 88 terms were significantly enriched (Table S7). The most significantly enriched GO terms were integral to membrane (GO: 0016021) with 338 genes annotated, followed by nucleus (GO: 0005634), cytoplasm (GO: 0005737), and extracellular region (GO: 0005576). In the biological processes, 205 GO terms were significantly enriched and were related to various processes (Table S8) such as proteolysis (GO: 0006508), apoptosis (GO: 0006915), cell adhesion (GO: 0007155), protein transport (GO: 0015031), protein folding (GO: 0006457), multicellular organismal development (GO: 0007275), and cell differentiation (GO: 0030154). The top 20 GO functional annotations for the DEGs are shown in Fig. 7. The inclusion of the annotation for insulin-like growth factor binding (GO: 0005520) and clathrin sculpted gamma-aminobutyric acid transport vesicle membrane (GO: 0061202) interested us, because previous studies have reported that IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor) and GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) may play important roles in the development of the receptive endometrium in mice and humans36,37,38,39.

Figure 7. Histogram presentation of the top 20 GO functional annotations for the DEGs.

The right x-axis indicates the number of genes in a category. The left y-axis indicates the specific category of GO.

KEGG Pathway Analysis of the DEGs

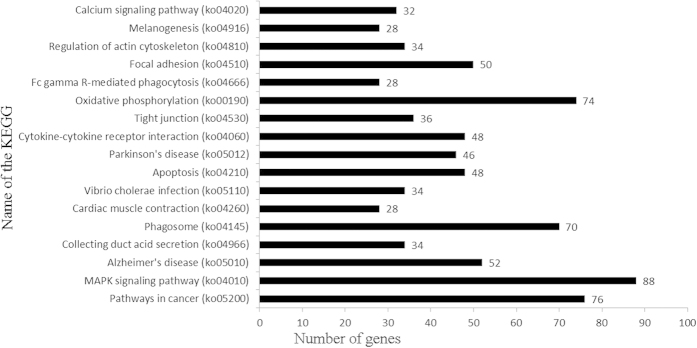

Various genes cooperate with each other to exercise their biological functions. Accordingly, KEGG analysis helps us to further understand the biological functions of DEGs40. Overall, the DEGs were significantly enriched in 82 KEGG pathways, meeting the criteria of P-values < 0.001 (Table S9), suggesting that these pathways may play important roles in the development of endometrial receptivity.

The KEGG pathways showing the highest levels of significance were the MAPK signalling pathway (ko04010, 88) with 88 DEGs enriched, followed by Pathways in cancer (ko05200, 76), Oxidative phosphorylation (ko00190, 74), Phagosome (ko04145, 70), Alzheimer’s disease (ko05010, 52), Focal adhesion (ko04510, 50), Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (ko04060, 48), and Apoptosis (ko04210, 48). The top 17 KEGG pathways are shown in Fig. 8. These results indicate that diversifying metabolic processes are active in the development of a receptive endometrium from the pre-receptive phase, and a variety of metabolites are synthesized in the receptive endometrium.

Figure 8. Histogram presentation of the top 17 KEGG functional annotations for the DEGs.

The x-axis indicates the number of unique sequences assigned to a specific pathway, the y-axis indicates the KEGG pathway.

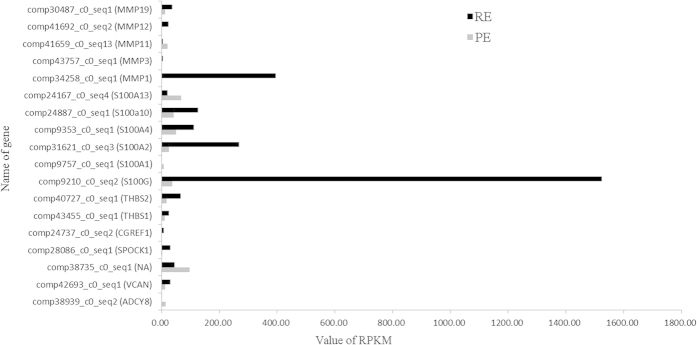

Genes Possibly Involved in the Development of Receptive Endometria

Our analysis identified many DEGs that were enriched in Calcium (GO: 0005509, GO: 0005509, GO: 0008294, and ko04020) and Cell adhesion (GO: 0045785, GO: 0007155, and ko04514) were significant according to the analysis results of both the GO terms and KEGG pathways (P < 0.001). Based on these results, we analysed the mRNA expression levels of some coding genes related to calcium and cell adhesion, and found that ADCY8, VCAN, NA, SPOCK1, CGREF1, THBS1, THBS2, S100G, S100A1, S100A2, S100A4, S100A10, S100A13, MMP1, MMP3, MMP11, MMP12, and MMP19 exhibited significantly different expression levels among the two endometrial phases (Fig. 9). Therefore, the results of this study suggested that these genes may play roles in the differential regulation of goat endometrial development during the receptive and pre-receptive phases; however, the validation of this hypothesis needs further study.

Figure 9. The expression levels of 18 genes exhibited significantly different expression about Calcium and Cell adhesion.

Discussion

Investigating the transcriptome profile of the receptive and pre-receptive endometrium will contribute to our understanding of the biochemical and physiological development of endometrial receptivity during the “window of implantation”. RNA-Seq offers an unprecedented level of sensitivity and high throughput deep sequencing and has been widely used to detect gene expression patterns10,12. In the present study, large-scale transcriptome data were obtained using Illumina RNA-Seq as the first step of our endeavour to provide clear insight into the molecular mechanism of endometrial receptivity in dairy goats.

Sequencing Results

Summary and validation of RNA-Seq

The RNA-Seq method has previously been widely used in many tissues and at developmental different stages41,42. Mamo’s research team summarized a large dataset to characterize the transcriptome of the endometrium and thought that most studies had tended to focus on either the conceptus or the maternal endometrium rather than the crosstalk between the two in cattle43. Therefore, they examined the global transcriptome profiles of the day 16 bovine conceptus and pregnant endometrial tissues using RNA-Seq, and a total of 133 conceptus ligands that interact with corresponding receptors on the endometrium and 121 endometrium ligands that interact with corresponding receptors on the conceptus were identified44. Additionally, Forde and her colleagues determined how low progesterone (P4) affected the endometrial transcriptome in cattle, and identified a panel of genes that were truly regulated in the endometrium by circulating concentrations of P4 in vivo45.

To characterize the complex transcriptome changes in the endometrium in the course of initial conceptus attachment, the porcine endometrium between Day 14 pregnancy (Attachment Phase) and corresponding cyclic endometrium was performed using Illumina RNA-Seq46. Furthermore, the endometrium transcriptome of day 12 pregnant (Preattachment Phase) was also analysed by Samborski47. Therefore, an integrated analysis of gene expression changes during these two distinct phases of early pregnancy in the pig was performed and revealed a number of biological processes and pathways that are potentially involved in the establishment of pregnancy in the pig.

Researchers would get some genes that were unidentified previously using RNA-Seq, what provided a useful approach to gain insights in the physiological events. However, current knowledge on the development of the receptive endometrium has been limited. Herein, for the first time we present a complete dataset detailing the transcriptome of the pre-receptive endometrium (PE) and receptive endometrium (RE) in dairy goats using the Illumina RNA-Seq approach to generate a total of 46,514,662 and 44,185,646 clean reads, respectively.

De novo assembly of sequencing data

Previous analyses of transcriptomic data always used the Velvet, ABySS, MIRA, Newbler v2.3, Newbler v2.5p, CLC, or TGICL software programmes for assembly11,48. However, all of these methods rely on aligning reads to a reference genome, and thus are unsuitable for samples with a partial or missing reference genome. Choosing suitable assemblers and parameters is critical to obtain a better assembly performance, and is even more important in transcriptomic studies in non-model organisms30. For these reasons, Grabherr presented the Trinity method for the de novo assembly of full-length transcripts and evaluated it on samples from fission yeast, mice and the whitefly, whose reference genomes are not yet available26. Compared with other transcriptome assemblers, Trinity recovers more full-length transcripts across a broad range of expression levels with a similar sensitivity to methods that rely on genome alignments26. Thus, the Trinity approach provides a unified solution for transcriptome reconstruction in any sample, especially in the absence of a reference genome. Thus we choose Trinity (http://trinityrnaseq.sourceforge.net/) to assembly and got 102,441 unigenes.

Unigene Annotation

All of the unigenes were BLASTed (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) to public database banks. A total of 43,127 coding genes were detected after the unigenes were annotated to SWISS-PROT, nr, KEGG, KOG, and Pfam. Additionally, 15,220 genes had BLAST hits in the nucleotide sequence database in nr, of which 4,612 (30.3%) matched with Ovis aries and 2,648 (17.4%) with Bos taurus. Orthologous genes have the same function and common ancestors29, and KOG is a classification system based on orthologous genes. In this study, most of the annotated genes were in the General functional prediction only (R) category, but no genes were annotated to the Unnamed protein (X) category. The dataset we report here is the largest dataset of different genes representing a substantial portion of the endometrial transcriptome, and most likely includes the majority of the genes involved in the sophisticated networks that regulate endometrial receptivity during embryo implantation.

Detecting SNP and SSR Variants by RNA-Seq

RNA-seq has been shown to be an efficient method to detect SNP variants on a large scale at the mRNA level12. A total of 100,734 SNPs were discovered in the milk from Holstein cattle using RNA-seq and were validated by Sanger sequencing technologies. The results confirmed that RNA-Seq technology is an efficient and cost-effective method to identify SNPs in transcribed regions49. In the present manuscript we supplied 76,729 putative SNPs in RE and 77,102 in PE, which will contribute to furthering our understanding of its development and functions.

SSRs have proven to be more reliable than other markers, and the utility of SSRs in genetic studies is well established30. The polymorphisms revealed by SSRs result from variations in repeat number, which primarily result from slipped-strand mispairing during DNA replication. Thus, SSRs reveal much higher levels of polymorphism than most other marker systems50,51. We screened 12,837 SSR loci in the endometrium transcriptome, of which the monomer repeats (47.12%) were the most frequent type.

Differential gene expression and functional characterization

Analysis of Gene Expression

Successful implantation and trophoblast invasion are facilitated by the degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the endometria/decidua52,53 by various proteinases, including the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that are capable of degrading the ECM54. MMP-2 and MMP-9 represent the best characterized proteases in the context of trophoblast invasion; additionally, MMP-12 was recently described to execute elastolysis during uterine spiral artery remodelling55. In our study, 3,255 unigenes meeting the criteria of P < 0.05 were found to differ significantly in expression levels between the RE and PE. The most up-regulated DEG was MMP-1 (comp34258_c0_seq1). MMP-1 is a zinc-containing endopeptidase that plays a key role in physiological and pathological tissue remodelling56,57,58. It was found to be secreted by trophoblast cells in vitro59, and Berthold found weak MMP-1 immuno-reactivities throughout pregnancy, preferably in the invasive phenotype of the extravillous trophoblast and its ECM60.

The up-regulated DEG with the highest expression level was S100G (S100 calcium binding protein G, comp9210_c0_seq2), which has been identified in the uteri of several species61,62,63,64. S100G expression was observed in the uterine inter-implantation sites in mice65 and endometrial epithelial cells in rats62 during early pregnancy. Further study showed that S100G was up-regulated by oestrogen66. However, studies have reported that the levels of S100G were higher in the luteal phase than in the follicular phase in the endometrium of pigs67. And this study demonstrated higher expression of S100G in the receptive endometrium of dairy goats for the first time. These findings suggested that endometrial S100G expression is regulated in a stage-specific manner during early pregnancy, and that S100G may have a critical role in regulating the development of endometrial receptivity.

In this study, CA1 (Carbonic anhydrase 1, comp43561_c1_seq2) was specifically expressed in the receptive endometrium of dairy goats. It is a member of the CA family68 and catalyses the reversible hydration/dehydration of carbon dioxide69. CA1 is considered to be a differentiation marker of the colonic mucosa, and the loss of CA1 expression is associated with the disappearance of differentiated epithelial cells70. Currently, little is known concerning the relationship between CA1 and endometrial receptivity during the “window of implantation” in dairy goats. Therefore, we propose that CA1 may be negatively involved in the development of the receptive endometrium from the pre-receptive phase in dairy goats; however, this hypothesis needs further exploration.

Additionally, MYH11 (myosin heavy chain 11, comp43544_c1_seq6) was decreased in the RE compared with the PE. MYH11 has been associated with cell migration and adhesion, intracellular transport, and signal transduction71. It encodes myosin-1172, a major contractile protein that converts chemical energy into mechanical energy through the hydrolysis of ATP71. And several studies have shown that myosin plays important roles in cancer73,74,75,76 due to its down-regulation77,78.

Based on these findings, we propose that S100G, CA1, and MYH11 may play important role in the development of the receptive endometrium from the pre-receptive phase. However, the molecular mechanism of the above genes in the regulation of endometrial receptivity requires further study.

Gene Ontology Analysis of the DEGs

In total, 426 GO terms were assigned to the DEGs meeting the criteria of P < 0.001, of which 133 GO terms were categorized into molecular function, 88 GO terms were categorized into cellular component and 205 GO terms were categorized into biological process. Further analyses showed that proteolysis, apoptosis, cell adhesion, protein transport, protein folding, multicellular organismal development, and cell differentiation were enriched significantly in biological processes. Previous studies have reported that increased proteolysis were found in the culture supernatant of endometrial tissues from women with endometriosis79. Controlled extracellular proteolysis is a requirement for angiogenesis (new vessel formation) that depended on controlled interactions between cells and the ECM80. Apoptosis, referred to as programmed cell death, is a process by which multiple cell types are eliminated during embryogenesis and in fully developed adult multicellular organisms46. Apoptosis is an important biological process involved in the cyclic remodelling of the endometrium27,81. Kokawa’s in situ analysis revealed that cells undergoing apoptosis were scattered in the functional layer of the early proliferative endometrium82. Accumulating evidence has suggested that apoptosis helps to maintain cellular homeostasis during the menstrual cycle through the elimination of senescent cells from the functional layer of the uterine endometrium during the late secretory and menstrual phases of the cycle79,82. Spontaneous apoptosis of eutopic and ectopic endometrial tissues is impaired in women with endometriosis, and this reduced susceptibility to apoptosis might permit the growth, survival and invasion of endometriotic tissue83,84. The unique cell adhesion of the trophoblast to the endometrial epithelium and the subsequent trophoblastic invasion of the maternal tissue is an essential element of embryo implantation85. Genes related to cell adhesion processes are particularly important for implantation and placenta formation, and Samborski reported that related categories were found as overrepresented for genes with higher expression in Day 14 pregnant endometrium as well as for genes with higher expression in Day 14 cyclic endometrium46. These represent important and necessary processes for the development of the receptive endometrium from the pre-receptive phase, the folded endometrial epithelial bilayer and the ability of the endometrium to acquire the adhesive properties that allow embryo adhesion and its subsequent invasion.

Additionally, 9 genes were significantly annotated to insulin-like growth factor binding (GO: 0005520). Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) mediates the growth-promoting activity of the hormone, induces endothelial cell migration and is involved in the regulation of angiogenesis86. Oestrogen has been shown to stimulate IGF-1 gene expression in the endometrium36,87, and a growing body of evidence supports interactions between oestrogen and the IGF signalling pathways88. Giudice et al. provided evidence of IGF-I involvement in endometrial growth regulation89, thereby promoting endothelial cell proliferation and differentiation90.

KEGG Pathway Analysis of the DEGs

These KEGG pathways with DEGs enriched provide a valuable resource for investigating specific processes, functions, and pathways, facilitated the identification of novel genes involved in the development of the receptive endometrium in goats during the ‘window of implantation’.

Previous studies have reported that cell cycle pathway can be rapidly elicited by oestradiol (E2) in the human and mouse uterus91,92,93. Progesterone has been found to inhibit endometrial cancer by inhibiting the cell cycle94, and Dai found that the number of endometrial cells in G1 is significantly increased following treatment with progesterone81. Moreover, a few cell cycle regulatory genes were discovered to be expressed within post-hatching and/or preimplantation blastocysts27. In this study, the KEGG pathway of Cell cycle (ko04110) with 22 DEGs enriched meet the criteria of P-values < 0.001. Samborski identified some genes that were more highly expressed at the mRNA level in the endometria of pigs on day 12 of pregnancy, and these genes were related to KEGG functional terms of the cell cycle47.

In addition, Mitko reported that a number of mRNAs that encode ECM proteins and components of the cytoskeleton are enriched in the bovine endometrium during the oestrous cycle, indicating a remodelling of the ECM in the endometrium and changes in the cytoskeleton of endometrial cells84. The possibility that trophoblasts are scavengers of endometrial ECM breakdown products is compelling, and the analyses of ECM receptors and associated molecules that may be present on the trophoblast cell membrane adjacent to these structures will shed light on their precise nature and function82. The levels of a number of molecules have been shown to peak during the “window of implantation”, particularly the ECM receptor integrin αvβ395. We found 24 DEGs enriched into the pathway of ECM-receptor interaction (ko04512), met the criteria of P-values < 0.001. Furthermore, temporally and spatially regulated changes in the expression of ECM molecules at the maternal-foetal interface during embryo implantation are crucial for blastocyst attachment, migration and invasion96.

Potential genes involved in the development of the receptive endometrium

In this study, we analyzed the enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways and found Calcium and Cell adhesion what aroused our interest based on the researches of predecessors. So we filtered the GO-terms and KEGG pathways related to Calcium (GO: 0005509, GO: 0005509, GO: 0008294, and ko04020) and Cell adhesion (GO: 0045785, GO: 0007155, and ko04514), what were significantly enriched for the DEGs from the receptive and pre-receptive endometria.

Large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (BκCa channels) were expressed in endometrial cells, affected embryo implantation by mediating endometrial receptive factors, and altered the activity of NF-κB and homeostasis of Ca2+ in the human endometrial cells97. S100A11 was a Ca2+-binding protein that interpreted the calcium fluctuations and elicited various cellular responses. Endometrial S100A11 was a crucial intermediator in EGF-stimulated embryo adhesion, endometrium receptivity, and immunotolerance via affecting Ca2+ uptake and released from intracellular Ca2+ stores, and down-regulation of S100A11 might cause reproductive failure98. In addition, Membrive reported that Calcium could potentiate the effect of estradiol on PGF2α production in the bovine endometrium99. Cell-cell adhesion between the conceptus trophectoderm and endometrial luminal epithelial cells is the final step for placentation, and various cell adhesion molecules are involved in this process100. The expression and function of cell adhesion molecules are very important for embryo implantation and the establishment of pregnancy101. What’s more, LAY reported that interleukin 11 regulated endometrial cancer cell adhesion and migration via STAT3102, and L1 cell adhesion molecule is a strong predictor for distant recurrence and overall survival in early stage endometrial cancer103.

Therefore, GO terms and/or KEGG pathways that were closely related to calcium and cell adhesion in our study provided much valuable information for future study of the molecular mechanism underlying the development of the receptive endometrium in goats. And then we analysed the mRNA expression levels of some putative coding genes and found that ADCY8, VCAN, SPOCK1, THBS1 and THBS2 were involved in the GO terms and KEGG pathways related to Calcium and Cell adhesion.

ADCY8 (adenylate cyclase 8) is a membrane-bound enzyme that catalyses the formation of cAMP from ATP in higher vertebrates104 after it is activated by calmodulin105,106. Previous findings showed that ADCY8 is required for axonal pathfinding before axons reach their targets, connecting mouse avoidance behaviour obtained in automated home cage environments to human bipolar affective disorder107. The findings in the present study point to novel mechanisms underlying the role of the regulatory factor in the formation of the receptive endometrium. VCAN is a chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan that was first identified in fibroblastic extracts108 and is abundantly expressed within the ECM of the developing and mature cardiovascular system109. Since the initial identification and characterization of VCAN, the functional importance of this chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan in multiple adult biological systems has been increasingly demonstrated110,111. Additionally, because it interacts directly with integrin, attachment-dependent signalling may be altered and affect cell migration and the epithelial mesenchymal transition in the cushion primordia of the septa and valves112,113. SPOCK1 (SPARC/osteonectin, cwcv and kazal-like domains proteoglycan 1) encodes testican-1, which is a proteoglycan belonging to the BM-40/SPARC/osteonectin family of extracellular calcium-binding proteins; SPOCK1 is widely expressed in the heart, blood and cartilage114,115,116,117. Miao identified SPOCK1 as a novel transforming growth factor-b1 (TGF-b) target gene that regulates the lung cancer cell epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which plays a key role in the early process of metastasis of cancer cells118. Moreover, a number of studies have demonstrated that SPOCK1 plays a critical role in prostate cancer recurrence and glioblastoma invasion119,120. Thus, we hypothesize that SPOCK1 plays an important role in the development of the receptive endometrium, although this hypothesis needs further study. THBS1 (thrombospondin 1) is a multifunctional glycoprotein that is involved in numerous biological processes, such as cellular adhesion, angiogenesis, metastasis, inflammation, atherosclerosis, homeostasis121,122. THBS1 is generally considered to be a tumour suppressor and mediates cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions that are important for platelet aggregation and angiogenesis123,124. THBS2 (Thrombospondin 2) is an ECM disulphide-linked homotrimeric glycoprotein95 that plays an important role in cell adhesion, migration and proliferation, cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions, and angiogenesis125. It has also been implicated in atherosclerosis and thrombosis due to its function in the regulation of matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2)126,127. Thus, THBS1 and THBS2 may play a major role in ECM homeostasis. However, only very limited data is available concerning the status of THBS1 and THBS2 in the development of the receptive endometrium, what needs further study.

In conclusion, we sequenced the transcriptome of dairy goats with the Illumina 2500 sequencing platform. Trinity software was used for de novo assembly of our valid reads. A total of 3,255 DEGs were discovered between the pre-receptive endometrium (PE) and the receptive endometrium (RE), with a threshold of P < 0.05. Based on the results of GO and KEGG enrichment, some genes potentially play an important role in the development of endometrial receptivity. Additionally, 76,729–77,102 putative SNPs and 12,837 SSRs were discovered in this study. Our results not only reveal new information regarding the development of dairy goat endometrial receptivity but also provide a broad and novel vision for future research at the molecular level in dairy goats.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animals in this study were maintained according to the No. 5 proclamation of the Ministry of Agriculture, P. R. China. And animal protocols were approved by the Review Committee for the Use of Animal Subjects of Northwest A&F University.

Study Design and Sample Collection

A total of 20 healthy, 24-month-old multiparous dairy goats (Xinong Saanen) were induced to oestrous synchronization for this study. The first day of mating was considered to be day 0 of pregnancy. Gestational days 5 and 15 are important time points for embryo implantation in goats128. The experimental goats were observed 3 times daily to ascertain oestrous signs and mated naturally twice during oestrus. Then, the goats were euthanized following intravenous injection of a barbiturate (30 mg/kg) at gestational day 5 (pre-receptive endometrium) and gestational day 15 (receptive endometrium). Endometrium samples from 10 goats at gestational day 5 and 10 goats at gestational day 15 were obtained from the anterior wall of the uterine cavity. All tissue samples were washed briefly with PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) and then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Library Construction and Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from every sample using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and DNA contamination was evaluated using DNase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The total RNA quantity and purity were analysis of Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, CA, USA) and RNA 6000 Nano LabChip Kit (Agilent, CA, USA) with RIN number > 7.0. The total RNA with lowest quality was not used for further study from the pre-receptive endometrium samples and receptive endometrium samples, respectively. Approximately 5 ug of total RNA was subjected to isolate Poly (A) mRNA with poly-T oligo attached magnetic beads (Invitrogen). Following purification, the mRNA was fragmented into small pieces using divalent cations under elevated temperature. Then the cleaved RNA fragments were reverse-transcribed to create the final cDNA library in accordance with the protocol for the mRNA-Seq sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Each PE and RE library was constructed by pooling 9 homogenized total RNAs from the endometrium samples. Then, paired-end sequencing of the PE and RE libraries was performed on the Illumina Hiseq2500 (LC Sciences, USA) following the vendor’s recommended protocol. The length of the reads was 100 bp, and the average insert size for the paired-end libraries was 179 bp (the length of the adapter was 121 bp).

Primary Analysis and Sequence Assembly

Prior to assembly, raw reads (raw data) in the fastq format were processed using previously described scripts29. In this step, clean reads (valid data) were obtained by removing reads containing adapter sequences, ploy-N and the sequencing primer as well as low quality reads (1, reads containing sequencing adaptors; 2, reads containing sequencing primer; 3, nucleotide with q quality score lower than 20) from the raw data. At the same time, Q20, Q30, GC-content and sequence duplication level of the clean data were calculated. All of the downstream analyses were based on high quality clean data. On the basis of previousresearch work26,36, the publicly available program Trinity (http://trinityrnaseq.source forge.net/) was selected for assembly in this study and used to calculate the N50 number, average length, max length and contig number during different length intervals.

Sequence Functional Annotation

Unigene annotations provide functional annotations for all unigenes in addition to their expression levels. Functional annotations of unigenes were analysed using protein sequence similarity by LC-Bio (Hangzhou, China). Protein function information could be predicted from annotations of the most similar proteins in the following published databases: SWISS-PROT (A manually annotated and reviewed protein sequence database, ftp://ftp.uniprot.org/pub/databases/uniprot/currentrelease/knowledgebase/complete/uniprot sprot.fasta.gz), NR (NCBI non-redundant protein sequences, ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ blast/db/FASTA/nr.gz), KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, http://www. kegg.jp/kegg/download/), KOG (Karyotic Ortholog Groups, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ COG/grace/shokog.cgi), and Pfam (A widely used protein family and structure domain database, ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/databases/Pfam/releases/Pfam27.0/Pfam-A.fasta.gz). All searches were conducted with BLASTx (http://blast.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/) using a minimum E-value of < 1e-10 as the threshold29,129.

Analysis of Gene Expression

To investigate the expression level of each unigene in different samples, all unigenes for each sample were aligned back to the final assembly using Perl scripts in Trinity under the default parameters option. The alignment produced digital expression levels for each contig that were normalized with a RESM-based algorithm using Perl scripts in the Trinity package to obtain RPKM values. Gene expression levels were normalized by considering the RPKM value (reads per kilobase of the exon model per million mapped reads) and the effect of the sequencing depth and gene length on the read counts; this approach represents the most commonly used method for estimating gene expression levels25. The fold changes (log2 (RERPKM/PERPKM)) and the corresponding significance threshold of the P-value were estimated according to the normalized gene expression level. Based on the expression levels, the significant DEGs between PE and RE were identified with “P < 0.05 and |log2 fold change|>1” used as the threshold to judge the DEGs in this study.

Gene ontology and pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs

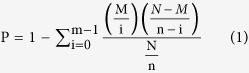

Gene ontology (GO) is an international standard gene functional classification system130. The hypergeometric test was applied to map all differentially expressed genes to terms in the GO database131. The corrected P-value < 0.001 was used as the threshold to find significantly enriched GO terms in the input list of DEGs compared to their genomic background. The formula of P-value was as follow (numbered 1):

|

The N represented the number of GO annotated genes in genome, n represented the number of differentially expressed genes in N. M represented the number of particular GO annotated genes in genome, m represented the number of particular GO annotated genes expressed differentially in M132. And then P was less than 0.001 was used as the threshold to judge significant enrichment GO term in this study10,12.

KEGG is the major public pathway-related database that helps to further understanding the biological functions of genes with high level functions and the utilities of the biological system from large-scale molecular datasets (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/)29. Pathway enrichment analysis identifies significantly enriched metabolic pathways or signal transduction pathways10 using the corrected P-value < 0.001 as a threshold to find significantly enriched KEGG terms in the input list of DEGs compared to their genomic background133. The calculation formula is the same as that used for the GO analysis.

Detection of Putative SNP and SSR

High-throughput SNP data has demonstrated its potential for making inferences about demographic and adaptive processes in natural populations134,135,136,137. The SNPs of PE and RE at the transcriptome level were analysed based on the massively parallel Illumina technology. The Bowtie (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/) and Samtools (http://samtools.sourceforge. net/) software programmes were used to identify SNPs; all reads were included in this process129. The sample data were mapped to the transcript with the Bowtie software after pretreatment based on the transcription library. Further SNP analysis was performed based on the results of mapping, and variable sites with higher possibilities were further filtered using the software Samtools.

The MISA (Microsatellite) (http://pgrc.ipkgatersleben.de/misa) was used to identify SSRs. The Batch Primer3 program was used to design primer pairs for amplification of the SSR motifs138. The default settings were used with the exception of the annealing temperature, which was set for an optimum of 60 °C129. Monomers, dimers, trimers, quadramers, pentamers and hexamers were all considered as the search criteria for SSRs in the MISA script.

Additional Information

Accession codes: All the basic data series were submitted to NCBI's Sequence Read Archive with accession number SRP056134

How to cite this article: Zhang, L. et al. Characterization of the Transcriptional Complexity of the Receptive and Pre-receptive Endometria of Dairy Goats. Sci. Rep. 5, 14244; doi: 10.1038/srep14244 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Support Program of China (2011BAD28B05-3) and Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shaanxi Province (2011KTCL02-09). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions L.Z. and Y.U.S. gathered samples, conceived the report, participated in its design, performed data analysis, interpreted results and drafted the manuscript. X.P.A., M.Z.F., J.X.H. and Z.Q.Z. participated in intellectual discussion. J.Y.P. and P.H. contributed to gathering samples. B.Y.C. designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Xia H. F., Jin X. H., Cao Z. F., Hu Y. & Ma X. MicroRNA expression and regulation in the uterus during embryo implantation in rat. FEBS J. 281, 1872–1891, 10.1111/febs.12751 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egashira M. & Hirota Y. Uterine receptivity and embryo–uterine interactions in embryo implantation: lessons from mice. Reproductive Medicine and Biology 12, 127–132 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons D. G. & Kennedy T. G. Uterine sensitization-associated gene-1: A novel gene induced within the rat endometrium at the time of uterine receptivity/sensitization for the decidual cell reaction. Biology of Reproduction 67, 1638–1645, 10.1095/bioreprod.102.006858 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revel A., Achache H., Stevens J., Smith Y. & Reich R. MicroRNAs are associated with human embryo implantation defects. Human reproduction, 26, 2830–2840, 10.1093/humrep/der255 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q., Luo X., Toloubeydokhti T. & Chegini N. The expression profile of micro-RNA in endometrium and endometriosis and the influence of ovarian steroids on their expression. Mol. Human Reprod. 13, 797–806, 10.1093/molehr/gam063 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmäe S. et al. MicroRNAs miR-30b, miR-30d, and miR-494 regulate human endometrial receptivity. Reproductive Sciences 20, 308–317 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J., Bunting L., Collins J. A. & Nygren K. G. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Human reproduction 22, 1506–1512 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklon N. S., Stouffer R. L., Giudice L. C. & Fauser B. C. The science behind 25 years of ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Endocr. Rev. 27, 170–207 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha A.-G. et al. Genome-wide identification of micro-ribonucleic acids associated with human endometrial receptivity in natural and stimulated cycles by deep sequencing. Fertility and sterility 96, 150–155. e155 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H. & Liu X. Characterization of Transcriptional Complexity during Longissimus Muscle Development in Bovines Using High-Throughput Sequencing. PloS one 8, e64356 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. & Blaxter M. L. Comparing de novo assemblers for 454 transcriptome data. BMC Genomics 11, 571 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. et al. Characterization of Transcriptional Complexity during Adipose Tissue Development in Bovines of Different Ages and Sexes. PloS one 9, e101261 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloonan N. & Grimmond S. M. Transcriptome content and dynamics at single-nucleotide resolution. Genome Biol 9, 234 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Ruan J. & Durbin R. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 18, 1851–1858 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagalakshmi U. et al. The transcriptional landscape of the yeast genome defined by RNA sequencing. Science 320, 1344–1349 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan M. et al. A global view of gene activity and alternative splicing by deep sequencing of the human transcriptome. Science 321, 956–960 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm B. T. et al. Dynamic repertoire of a eukaryotic transcriptome surveyed at single-nucleotide resolution. Nature 453, 1239–1243 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AC’t Hoen P. et al. Deep sequencing-based expression analysis shows major advances in robustness, resolution and inter-lab portability over five microarray platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, e141–e141 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni J. C., Mason C. E., Mane S. M., Stephens M. & Gilad Y. RNA-seq: an assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Res. 18, 1509–1517 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H.-F. et al. Temporal and spatial regulation of miR-320 in the uterus during embryo implantation in the rat. International journal of molecular sciences 11, 719–730 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venners S. A. et al. Urinary estrogen and progesterone metabolite concentrations in menstrual cycles of fertile women with non-conception, early pregnancy loss or clinical pregnancy. Human Reproduction 21, 2272–2280 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga K. Review of factors essential for blastocyst implantation for their modulating effects on the maternal immune system in Seminars. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 161–169 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q.-H., Peng J.-P., Xia H.-F., Yang Y. & Liu M.-L. Effect on expression of RT1-A and RT1-DM molecules of treatment with interferon-γ at the maternal—fetal interface of pregnant rats. Human Reproduction 20, 2639–2647 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C. T. et al. Circulating insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF binding proteins-1 and-3 and placental development in the guinea-pig. Placenta 23, 763–770, 10.1053/plac.2002.0849 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., McCue K., Schaeffer L. & Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 5, 621–628 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood D. & Levison D. Atrophy and apoptosis in the cyclical human endometrium. The Journal of pathology 119, 159–166 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q. et al. De novo transcriptome sequencing and digital gene expression analysis predict biosynthetic pathway of rhynchophylline and isorhynchophylline from Uncaria rhynchophylla, a non-model plant with potent anti-alzheimer’s properties. BMC Genomics 15, 676 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Gao F., Liu R., Feng J. & Li H. De novo sequencing and analysis of root transcriptome using 454 pyrosequencing to discover putative genes associated with drought tolerance in Ammopiptanthus mongolicus. BMC Genomics 13, 266 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P., Balyan H., Sharma P. & Ramesh B. Microsatellites in plants: a new class of molecular markers. Curr. Sci. 45, 45–54 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Noormohammadi Z., Trujillo I., Belaj A., Ataei S. & Hosseini-Mazinan M. Genetic structure of Iranian olive cultivars and their relationship with Mediterranean’s cultivars revealed by SSR markers. Scientia Horticulturae 178, 175–183, 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.08.002 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xing R. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of Armillaria luteovirens (Physalacriaceae) in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau revealed by SSR markers. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 56, 1–7, 10.1016/j.bse.2014.04.006 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. D. & Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol 11, R25 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner T. Next generation sequencing in functional genomics. Briefings in bioinformatics 11, 499–511 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutanen E.-M. Insulin-like growth factors and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in the endometrium. Effect of intrauterine levonorgestrel delivery. Human Reproduction 15, 173–181 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quezada M. et al. Proenkephalin A and the γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor π subunit: expression, localization, and dynamic changes in human secretory endometrium. Fertility and sterility 86, 1750–1757 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyster K. M., Klinkova O., Kennedy V. & Hansen K. A. Whole genome deoxyribonucleic acid microarray analysis of gene expression in ectopic versus eutopic endometrium. Fertility and sterility 88, 1505–1533 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi H. & Taylor H. S. HOXA10 regulates endometrial GABAA π receptor expression and membrane translocation. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 298, E889–E893 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. et al. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D199–D205 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe S., Rincon G., Islas-Trejo A. & Medrano J. F. Transcriptional profiling of bovine milk using RNA sequencing. BMC Genomics 13, 45 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrano J. et al. Comparative analysis of bovine milk and mammary gland transcriptome using RNA-Seq. 9th World Congress of Genetics Applied to Livestock Production (WCGALP), Leipzig-Germany, No. 0852 (2010).

- Mamo S., Rizos D. & Lonergan P. Transcriptomic changes in the bovine conceptus between the blastocyst stage and initiation of implantation. Animal Reproduction Science 134, 56–63, 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2012.08.011 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamo S., Mehta J. P., Forde N., McGettigan P. & Lonergan P. Conceptus-Endometrium Crosstalk During Maternal Recognition of Pregnancy in Cattle. Biology of Reproduction 87, 10.1095/biolreprod.112.099945 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde N. et al. Effects of Low Progesterone on the Endometrial Transcriptome in Cattle. Biology of Reproduction 87, 10.1095/biolreprod.112.103424 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samborski A., Graf A., Krebs S., Kessler B. & Bauersachs S. Deep sequencing of the porcine endometrial transcriptome on day 14 of pregnancy. Biology of reproduction 88, 84 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samborski A. et al. Transcriptome Changes in the Porcine Endometrium During the Pre-attachment Phase. Biology of reproduction. 89, 10.1095/biolreprod.113.112177 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R. et al. Gene discovery and tissue-specific transcriptome analysis in chickpea with massively parallel pyrosequencing and web resource development. Plant Physiol. 156, 1661–1678 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cánovas A., Rincon G., Islas-Trejo A., Wickramasinghe S. & Medrano J. F. SNP discovery in the bovine milk transcriptome using RNA-Seq technology. Mamm. Genome 21, 592–598 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth G., Gáspári Z. & Jurka J. Microsatellites in different eukaryotic genomes: survey and analysis. Genome Res. 10, 967–981 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. C., Korol A. B., Fahima T., Beiles A. & Nevo E. Microsatellites: genomic distribution, putative functions and mutational mechanisms: a review. Mol. Ecol. 11, 2453–2465 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagel S., Parhar R. S., Jeffrey J. J. & Lala P. K. Normal nonmetastatic human trophoblast cells share in vitro invasive properties of malignant cells. Journal of cellular physiology 136, 455–462 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin J. D. Implantation, trophoblast differentiation and hæmochorial placentation: mechanistic evidence in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Sci 99, 681–692 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkedal-Hansen H. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases: a review. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine 4, 197–250 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L. K. et al. Trophoblast-and vascular smooth muscle cell-derived MMP-12 mediates elastolysis during uterine spiral artery remodeling. The American journal of pathology 177, 2103–2115 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinckerhoff C. E. & Matrisian L. M. Timeline - Matrix metalloproteinases: a tail of a frog that became a prince. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 3, 207–214, 10.1038/nrm763 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo A. & Selman M. MMP-1: the elder of the family. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 37, 283–288 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I. et al. Structural Basis for Matrix Metalloproteinase 1-Catalyzed Collagenolysis. Journal of the American Chemical Society 134, 2100–2110, 10.1021/ja208338j (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emonard H., Christiane Y., Smet M., Grimaud J. & Foidart J.-M. Type IV and interstitial collagenolytic activities in normal and malignant trophoblast cells are specifically regulated by the extracellular matrix. Invasion & metastasis 10, 170–177 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz B., Kertschanska S., Demir A. Y., Frank H. G. & Kaufmann P. Immunohistochemistry of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), their substrates, and their inhibitors (TIMP) during trophoblast invasion in the human placenta. Cell and Tissue Research 291, 133–148 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi K. et al. Expression of calcium binding protein D-9k messenger RNA in the mouse uterine endometrium during implantation. Mol. Human Reprod. 5, 153–161 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warembourg M., Perret C. & Thomasset M. Analysis and in situ detection of cholecalcin messenger RNA (9000 Mr CaBP) in the uterus of the pregnant rat. Cell and tissue research 247, 51–57 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisinger J., Jeung E.-B., Simmen R. & Leung P. Porcine calbindin-D9k gene: expression in endometrium, myometrium, and placenta in the absence of a functional estrogen response element in intron A. Biology of reproduction 52, 115–123 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Seo H., Kim M. & Ka H. Dynamic expression of calcium-regulatory molecules, TRPV6 and S100G, in the uterine endometrium during pregnancy in pigs. Biology of reproduction 81, 1122–1130 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie G.-Y., Wang Y. L. J., Minoura H., Findlay J. K. & Salamonsen L. A. Complex regulation of calcium-binding protein D9k (Calbindin-D9k) in the mouse uterus during early pregnancy and at the site of embryo implantation. Biology of reproduction 62, 27–36 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. C. & Jeung E. B. Molecular mechanism of regulation of the calcium‐binding protein calbindin‐D9k, and its physiological role (s) in mammals: a review of current research. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 12, 409–420 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun S. M. et al. Dominant expression of porcine Calbindin‐D9k in the uterus during a luteal phase. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 67, 251–256 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supuran C. T., Fiore A. D. & Simone G. D. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors as emerging drugs for the treatment of obesity. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs, 13, 383–392 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufts B., Esbaugh A. & Lund S. Comparative physiology and molecular evolution of carbonic anhydrase in the erythrocytes of early vertebrates. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 136, 259–269 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowden J., Leigh S., Talbot I., Delhanty J. & Edwards Y. Expression from the proximal promoter of the carbonic anhydrase 1 gene as a marker for differentiation in colon epithelia. Differentiation 53, 67–74 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.-J. et al. Down-regulated MYH11 expression correlates with poor prognosis in stage II and III colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 15, 7223–7228 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka R. et al. Human smooth muscle myosin heavy chain gene mapped to chromosomal region 16q12. American journal of medical genetics 46, 61–67 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loikkanen I. et al. Myosin VI is a modulator of androgen-dependent gene expression. Oncol. Rep. 22, 991 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W.-j. et al. Myosin light chain kinase is responsible for high proliferative ability of breast cancer cells via anti-apoptosis involving p38 pathway. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 31, 725–732 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessina P. et al. Skeletal muscle of gastric cancer patients expresses genes involved in muscle regeneration. Oncol. Rep. 24, 741–745 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. et al. Role of MYH Polymorphisms in Sporadic Colorectal Cancer in China: A Case-control, Population-based Study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 14, 6403–6409 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz S. et al. Genetic background of different cancer cell lines influences the gene set involved in chromosome 8 mediated breast tumor suppression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 45, 612–627 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. et al. Cross-species comparison of orthologous gene expression in human bladder cancer and carcinogen-induced rodent models. American journal of translational research 3, 8 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collette T. et al. Evidence for an increased release of proteolytic activity by the eutopic endometrial tissue in women with endometriosis and for involvement of matrix metalloproteinase‐9. Human Reproduction 19, 1257–1264 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosín R. et al. Influence of peritoneal fluid on the expression of angiogenic and proteolytic factors in cultures of endometrial cells from women with endometriosis. Human reproduction 25, 398–405 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béliard A., Noël A. & Foidart J.-M. Reduction of apoptosis and proliferation in endometriosis. Fertility and sterility 82, 80–85 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokawa K., Shikone T. & Nakano R. Apoptosis in the human uterine endometrium during the menstrual cycle. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 81, 4144–4147 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.-Q. et al. CXCL8 enhances proliferation and growth and reduces apoptosis in endometrial stromal cells in an autocrine manner via a CXCR1-triggered PTEN/AKT signal pathway. Human reproduction 27, 2107–2116 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanowski K. Apoptosis pattern in human endometrium in women with pelvic endometriosis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 132, 107–110 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N. et al. A cytoplasmic protein, bystin, interacts with trophinin, tastin, and cytokeratin and may be involved in trophinin-mediated cell adhesion between trophoblast and endometrial epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95, 5027–5032 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A., Singh N., Gupta S., Rana J. & Gupta N. Relative expression of cell growth regulatory genes insulin-like growth factors (IGF-1 and IGF-2) and their receptors (IGF-1R and IGF-2R) in somatic cell nuclear transferred (SCNT) and in vitro fertilized (IVF) pre-implantation buffalo embryos. Cell Biol. Int. 33, 555–564 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutanen E.-M. Insulin-like growth factors in endometrial function. Gynecological Endocrinology 12, 399–406 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soufla G., Sifakis S. & Spandidos D. A. FGF2 transcript levels are positively correlated with EGF and IGF-1 in the malignant endometrium. Cancer Lett. 259, 146–155 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudice L. et al. Physiology: Insulin-like growth factor (IGF), IGF binding protein (IGFBP), and IGF receptor gene expression and IGFBP synthesis in human uterine leiomyomata. Human Reproduction 8, 1796–1806 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. & Jain R. K. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 407, 249–257 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayisli O. G., Kayisli U. A., Luleci G. & Arici A. In vivo and in vitro regulation of Akt activation in human endometrial cells is estrogen dependent. Biology of reproduction 71, 714–721 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W. & Pollard J. W. Progesterone inhibits estrogen-induced cyclin D1 and cdk4 nuclear translocation, cyclin E-and cyclin A-cdk2 kinase activation, and cell proliferation in uterine epithelial cells in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 2251–2264 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuokkanen S. et al. Genomic profiling of microRNAs and messenger RNAs reveals hormonal regulation in microRNA expression in human endometrium. Biology of reproduction 82, 791–801 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosik D., Jacobs S. & Kelly L. Endometrial tissue in peritoneal fluid. Fertility and sterility 46, 796–800 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laherty C. et al. Characterization of mouse thrombospondin 2 sequence and expression during cell growth and development. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 3274–3281 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haouzi D. et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals dialogues between human trophectoderm and endometrial cells during the implantation period. Human reproduction 26, 1440–1449 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.-J. et al. Functional expression of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in human endometrium: a novel mechanism involved in endometrial receptivity and embryo implantation. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 97, 543–553 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-M. et al. Down-regulation of S100A11, a calcium-binding protein, in human endometrium may cause reproductive failure. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 97, 3672–3683 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert C. et al. Effect of physical exercise on changes in activities of creatine kinase, cytochrome c oxidase and ATP levels caused by ovariectomy. Metab. Brain Dis. 29, 825–835, doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9564-x (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt R. C. et al. Integrins and extracellular matrix proteins at the maternal-fetal interface in domestic animals. Cells, tissues, organs 172, 202–217 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]