Abstract

Coevolution with bacteriophages is a major selective force shaping bacterial populations and communities. A variety of both environmental and genetic factors has been shown to influence the mode and tempo of bacteria–phage coevolution. Here, we test the effects that carriage of a large conjugative plasmid, pQBR103, had on antagonistic coevolution between the bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens and its phage, SBW25ϕ2. Plasmid carriage limited bacteria–phage coevolution; bacteria evolved lower phage-resistance and phages evolved lower infectivity in plasmid-carrying compared with plasmid-free populations. These differences were not explained by effects of plasmid carriage on the costs of phage resistance mutations. Surprisingly, in the presence of phages, plasmid carriage resulted in the evolution of high frequencies of mucoid bacterial colonies. Mucoidy can provide weak partial resistance against SBW25ϕ2, which may have limited selection for qualitative resistance mutations in our experiments. Taken together, our results suggest that plasmids can have evolutionary consequences for bacteria that go beyond the direct phenotypic effects of their accessory gene cargo.

Keywords: bacteria–phage coevolution, conjugative plasmid, mucoid conversion

1. Introduction

Lytic phages are abundant in natural environments and a major cause of bacterial mortality [1]. It is increasingly recognized that bacteria–phage coevolution, the reciprocal evolution of bacterial resistance and phage infectivity, is an important evolutionary process shaping microbial communities [2,3]. Many factors, both environmental and genetic, have been shown to affect this process [4]. For example, both the mode and tempo of coevolution is strongly dependent on factors affecting genetic variation or the strength of reciprocal selection, such as mutation rate [5], population mixing [6–8], or resource availability [9,10]. Environmental variables can also lead to qualitative differences in the evolutionary response to phage infection, for instance favouring different forms of resistance in different environments [6,11]. In addition, bacterial genetic background can affect the outcome of bacteria–phage coevolution: for example, epistatic interactions between the costs of deleterious mutations and phage resistance mutations can constrain the rate of bacterial resistance evolution and thereby limit the rate of coevolution [12].

Conjugative plasmids, like phages, are ubiquitous in bacterial populations and drive bacterial genomic diversity through horizontal gene transfer [13]. While the accessory genes carried on plasmids can be highly beneficial to bacteria in some environments, plasmid acquisition represents a major change to bacterial genomic content, leading to biosynthetic costs and cellular disruption [14,15]. Furthermore, plasmid acquisition can increase the vulnerability of bacterial cells to environmental stressors [16]. Plasmid carriage is therefore likely to impact upon bacteria–phage coevolution, but this possibility, to our knowledge remains untested. We explored this using experimental coevolution of laboratory communities of the lytic phage SBW25ϕ2 and its host bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 either with or without the plasmid pQBR103; a conjugative 425Kb mercury resistance plasmid [17] isolated from the same soil community as SBW25 [18]. Following c.130 bacterial generations of coevolution, we assessed the relative bacterial resistance and phage infectivity phenotypes that evolved in each treatment using a cross-infection assay.

2. Methods

(a). Strains and culture conditions

Populations of P. fluorescens SBW25-Gm with or without plasmid pQBR103 [19] were initiated from single clones. Six replicate populations were established for each of four factorial combinations of plasmid (with or without) and phage (with or without) treatments. All populations were founded with approximately 108 bacterial cells plus approximately 106 SBW25ϕ2 particles in phage-containing treatments, and cultured in 30 ml microcosms containing 6 ml of King's broth (KB) supplemented with 8 µM HgCl2 to ensure retention of the plasmid [19]. Preliminary experiments showed that at 8 µM HgCl2 there was no significant difference in growth between plasmid-containing and plasmid-free cultures (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Populations were incubated at 28°C, shaken at 180 rpm and propagated by transferring 1% to fresh media every 48 h for 20 transfers. Bacteria and phages were plated at every fourth transfer to measure phage and bacterial density, plasmid prevalence [19] and colony morphology [20] (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

(b). Measuring bacterial resistance/phage infectivity

Resistance/infectivity was measured as the Reduction in Bacterial Growth (RBG) associated with phage co-culture (adapted from Poullain et al. [21]). Phage populations and 20 randomly picked bacterial clones were isolated from each phage containing population at transfer 20. Bacterial clones were then grown up in 150 µl KB in 96-well plates either alone or in the presence of each of the 12 phages populations. Cultures were incubated at 28°C and density measured at 0 and 20 h growth. RBG values were estimated for each interaction as

| 3.1 |

where OD stands for optical density at 600 nm. RBG estimates for the ancestral strains show that both ancestral plasmid-free and plasmid-containing strains were highly susceptible to ancestral phage infection (electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

(c). Estimating epistasis between costs of plasmid carriage and phage resistance

To test for an effect of plasmid carriage on the costs of phage resistance mutations, competitive fitness assays of eight spontaneous phage resistance mutants [19] and the phage-sensitive ancestor with and without the plasmid were performed in triplicate. Overnight cultures of each strain were mixed 1 : 1 with an isogenic lacZ-marked P. fluorescens SBW25 and inoculated into 6 ml of KB supplemented with 8 µM HgCl2 and grown for 48 h. Samples were plated at 0 and 48 h onto KB agar supplemented with X-gal, and relative fitness was calculated as the ratio of Malthusian parameters of competing strains [22].

3. Results and discussion

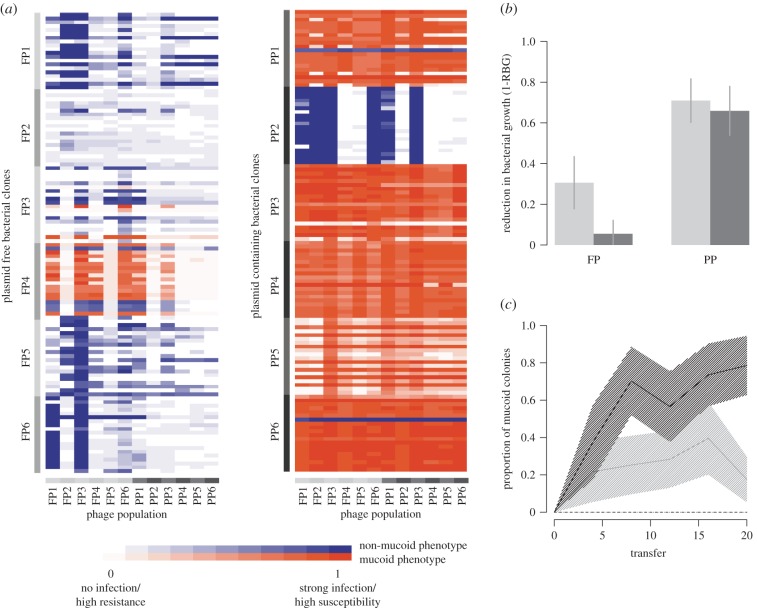

Plasmid carriage constrained both the evolution of bacterial resistance and phage infectivity. Plasmid-free bacteria evolved significantly higher rates of phage resistance compared with plasmid-carrying bacteria (figure 1a,b; PLASMID TREATMENTBACTERIA χ2 = 166.5, p < 0.0001). Phage infectivity, however, was dependent on which treatment bacteria were isolated from (PLASMID TREATMENTBACTERIA × PLASMID TREATMENTPHAGE χ2 = 85.5, p < 0.0001). When challenged against plasmid-carrying bacteria, phages from both treatments were equally infectious (PLASMID TREATMENTPHAGE χ2 = 0.546, p = 0.46). However, against plasmid-free bacteria, phages from the plasmid-containing treatment were significantly less infectious than phages from the plasmid-free treatment (PLASMID TREATMENTPHAGE χ2 = 6.62, p = 0.0101).

Figure 1.

Bacterial responses to phage infection. (a) Infection heat maps of pairwise interactions between the 120 bacterial clones (20 per population, six populations per treatment) from the plasmid-free (FP1-FP6; left) and plasmid-containing (PP1-PP6; right) populations with phage populations from both treatments (n = 12). Bacterial clones are grouped by population along the y-axis and phage populations grouped by treatment along the x-axis, indicated by grey tabs. Colours denote the mucoid status of each clone with intensity scaled by 1-RBG value (where darker indicates high 1-RBG and therefore phage infection). (b) Mean reduction in bacterial growth owing to phage predation (1-RBG) for bacterial clones from the plasmid-free (FP) and plasmid-containing (PP) treatments challenged against phages isolated from the plasmid-free (light) and plasmid-containing (dark) treatments. Lines show standard error of population means (n = 6). (c) Mean frequency of mucoidy over time. Lines show means (n = 6) for the four treatments; plasmid-containing treatments are shown in black and plasmid-free in grey. Phage-containing treatments are shown as fixed lines and phage-free control lines shown as dashed. Shading indicates standard error.

Our results therefore suggest that the carrying pQBR103 constrained bacterial resistance evolution, which in turn weakened selection for phage infectivity. One possible explanation for this is that plasmid carriage exacerbated the cost of phage resistance mutations, making resistance disproportionately costly and thereby limiting bacterial evolution [12]. To test this hypothesis, we measured the fitness of eight spontaneous phage-resistant mutants with and without the plasmid. In the ancestral SBW25 background, the plasmid did not significantly alter bacterial fitness (t2.12 = −0.026, p = 0.982). This was expected as experiments were conducted in mercury-supplemented media to ensure plasmid retention. In the phage-resistant backgrounds, we observed no evidence that plasmid-carriage affected the cost of phage resistance (electronic supplementary material, figure S4; for each clone p > 0.1). Indeed, in all but one case, plasmid-carriage appeared to alleviate the cost of phage resistance although this was significant in only two clones (A2 t3.98 = −3.201, p = 0.033 and E5 t3.226 = −5.649, p = 0.009). It is unlikely therefore that negative epistatic interactions constrained bacteria–phage coevolution in our experiment.

Surprisingly, we observed significant effects of the plasmid on bacterial colony morphology. In the presence of phages, bacteria evolved a mucoid colony morphology [11,20] (z = 30.83, p < 0.0001), with far higher mucoidy frequencies among plasmid-carrying compared to plasmid-free populations exposed to phage (figure 1c; z = 4.473, p < 0.0001). Whereas mucoidy transiently appeared in five out of six plasmid-free populations, [20,23], mucoidy approached fixation in five out of six replicates (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Transient mucoidy in the plasmid-free populations is consistent with previous studies of this bacteria–phage system [24]: without plasmids, mucoidy occurs in response to phages but rarely reaches high frequencies except under restricted culturing conditions [20,23]. Together this suggests that the emergence of the mucoid phenotype was not directly linked to plasmid carriage, for instance, owing to specific plasmid-encoded genes, but that plasmid carriage and phage attack interacted to select for the evolution of mucoidy in P. fluorescens.

Mucoidy is caused by over-production of alginate and provides partial resistance to phages in this and other bacteria–phage interactions [20,23,25,26]. Thus, it appears likely that mucoidy may have evolved in place of qualitative (all-or-nothing) resistance in plasmid-carrying bacteria, and this in turn weakened selection for the evolution of qualitative resistance. Mucoidy is thought to act as a global stress response to varied environmental pressures in Pseudomonads [27–29] and is an important virulence factor in human chronic lung infections [30,31]. Our findings suggest that combined exposure to both phages [32] and plasmids [33] in Pseudomonas chronic infections could exacerbate selection for mucoidy, hastening the onset of mucoid conversion and potentially worsening patient health, raising concerns about use of phage therapy in such infections.

These data add to a growing appreciation that plasmid carriage can have complex effects on the bacterial phenotype: plasmids have been shown to alter biofilm formation [16,34], cell hydrophicity [35], tolerance to stress and motility [16]. We show that plasmid carriage can also alter biotic interactions with phages, limiting bacteria–phage coevolution and altering the longer-term evolutionary trajectory of bacterial populations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Data accessibility

Data are available from Dryad: doi:10.5061/dryad.4622g.

Authors' contributions

M.B., S.P. and A.S. gained funding; M.B., S.P. and E.H. devised the study; E.H., J.T. and R.W. conducted the experiments; E.H. and R.W. analysed the data; E.H. and M.A.B. drafted the manuscript; all authors commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme awarded to M.A.B. (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC grant (StG-2012-311490-COEVOCON), a standard grant from the Natural Environment Research Council UK awarded to M.A.B., S.P. and A.J.S. (NE/H005080), and an NERC studentship supervised by S.P. and M.A.B.

References

- 1.Weinbauer MG. 2004. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28, 127–181. ( 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.08.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koskella B. 2013. Phage-mediated selection on microbiota of a long-lived host. Curr. Biol. 23, 1256–1260. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos M, Birkett PJ, Birch E, Griffiths RI, Buckling A. 2009. Local adaptation of bacteriophages to their bacterial hosts in soil. Science 325, 833–833 ( 10.1126/science.1174173) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckling A, Brockhurst M. 2012. Bacteria-virus coevolution. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 751, 347–370. ( 10.1007/978-1-4614-3567-9_16) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan AD, Bonsall MB, Buckling A. 2010. Impact of bacterial mutation rate on coevolutionary dynamics between bacteria and phages. Evolution 64, 2980–2987. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01037.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogwill T, Fenton A, Brockhurst MA. 2008. The impact of parasite dispersal on antagonistic host–parasite coevolution. J. Evol. Biol. 21, 1252–1258. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01574.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brockhurst MA, Morgan AD, Rainey PB, Buckling A. 2003. Population mixing accelerates coevolution. Ecol. Lett. 6, 975–979. ( 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00531.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez P, Ashby B, Buckling A. 2015. Population mixing promotes arms race host-parasite coevolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20142297 ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.2297) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Pascua LDC, Buckling A. 2008. Increasing productivity accelerates host–parasite coevolution. J. Evol. Biol. 21, 853–860. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01501.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison E, Laine A-L, Hietala M, Brockhurst MA. 2013. Rapidly fluctuating environments constrain coevolutionary arms races by impeding selective sweeps. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20130937 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.0937) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scanlan PD, Hall AR, Blackshields G, Friman VP, Davis MR, Goldberg JB, Buckling A. 2015. Coevolution with bacteriophages drives genome-wide host evolution and constrains the acquisition of abiotic-beneficial mutations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1425–1435. ( 10.1093/molbev/msv032) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buckling A, Wei Y, Massey RC, Brockhurst MA, Hochberg ME. 2006. Antagonistic coevolution with parasites increases the cost of host deleterious mutations. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 45–49. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3279) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman A, Hansen LH, Sorensen SJ. 2009. Conjugative plasmids: vessels of the communal gene pool. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2275–2289. ( 10.1098/rstb.2009.0037) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bragg JG, Wagner A. 2009. Protein material costs: single atoms can make an evolutionary difference. Trends Genet. 25, 5–8. ( 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baltrus DA. 2013. Exploring the costs of horizontal gene transfer. Trends Ecol. Evol. 28, 489–495. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2013.04.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dougherty K, Smith BA, Moore AF, Maitland S, Fanger C, Murillo R, Baltrus DA. 2014. Multiple phenotypic changes associated with large-scale horizontal gene transfer. PLoS ONE 9, e102170 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0102170) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tett A, et al. 2007. Sequence-based analysis of pQBR103; a representative of a unique, transfer-proficient mega plasmid resident in the microbial community of sugar beet. ISME J. 1, 331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lilley AK, Bailey MJ. 1997. The acquisition of indigenous plasmids by a genetically marked pseudomonad population colonizing the sugar beet phytosphere is related to local environmental conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 1577–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison E, Wood AJ, Dytham C, Pitchford JW, Truman J, Spiers AJ, Paterson S, Brockhurst MA. 2015. Bacteriophages limit the existence conditions for conjugative plasmids. mBio 6, e00586-15 ( 10.1128/mBio.00586-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogwill T, Fenton A, Brockhurst MA. 2011. Coevolving parasites enhance the diversity-decreasing effect of dispersal. Biol. Lett. 7, 578–580. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0071) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poullain V, Gandon S, Brockhurst M, Buckling A, Hochberg M. 2008. The evolution of specificity in evolving and coevolving antagonistic interactions between a bacteria and its phage. Evolution 62, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenski RE, Rose MR, Simpson SC, Tadler SC. 1991. Long-term experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. 1. Adaptation and divergence during 2,000 generations. Am. Nat. 138, 1315–1341. ( 10.1086/285289) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scanlan PD, Buckling A. 2012. Co-evolution with lytic phage selects for the mucoid phenotype of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25. ISME J. 6, 1148–1158. ( 10.1038/ismej.2011.174) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brockhurst MA, Morgan AD, Fenton A, Buckling A. 2007. Experimental coevolution with bacteria and phage the Pseudomonas fluorescens - Phi 2 model system. Infect. Genet. Evol. 7, 547–552. ( 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.01.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer CR, Yoichi M, Unno H, Tanji Y. 2004. The coexistence of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and its specific bacteriophage in continuous culture. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 241, 171–177. ( 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.10.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S. 2010. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 317–327. ( 10.1038/nrmicro2315) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathee K, et al. 1999. Mucoid conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by hydrogen peroxide: a mechanism for virulence activation in the cystic fibrosis lung. Microbiology-Sgm 145, 1349–1357. ( 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1349) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terry JM, Pina SE, Mattingly SJ. 1992. Role of energy-metabolism in conversion of nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the mucoid phenotype. Infect. Immun. 60, 1329–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood LF, Leech AJ, Ohman DE. 2006. Cell wall-inhibitory antibiotics activate the alginate biosynthesis operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: roles of sigma(22) (AlgT) and the AlgW and Prc proteases. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 412–426. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05390.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman FT, Mueschenborn S, Meluleni G, Ray C, Carey VJ, Vargas SO, Cannon CL, Ausubel FM, Pier GB. 2003. Hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis mice to chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa oropharyngeal colonization and lung infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1949–1954. ( 10.1073/pnas.0437901100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henry RL, Mellis CM, Petrovic L. 1992. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a marker of poor survival in cystic-fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 12, 158–161. ( 10.1002/ppul.1950120306) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tejedor C, Foulds J, Zasloff M. 1982. Bacteriophages in sputum of patients with bronchopulmonary Pseudomonas infections. Infect. Immun. 36, 440–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livermore DM. 2002. Multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: our worst nightmare? Clin. Infect. Dis. 34, 634–640. ( 10.1086/338782) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghigo JM. 2001. Natural conjugative plasmids induce bacterial biofilm development. Nature 412, 442–445. ( 10.1038/35086581) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zgoda A, Chablain P, Mater D, Truffaut N, Barbotin JN, Thomas D. 2001. A relationship between RP4 plasmid acquisition and phenotypic changes in Pseudomonas fluorescens R2fN. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 79, 173–178. ( 10.1023/A:1010262817895) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from Dryad: doi:10.5061/dryad.4622g.