Abstract

Organisms have evolved under natural daily light/dark cycles for millions of years. These cycles have been disturbed as night-time darkness is increasingly replaced by artificial illumination. Investigating the physiological consequences of free-living organisms in artificially lit environments is crucial to determine whether nocturnal lighting disrupts circadian rhythms, changes behaviour, reduces fitness and ultimately affects population numbers. We make use of a unique, large-scale network of replicated field sites which were experimentally illuminated at night using lampposts emanating either red, green, white or no light to test effect on stress hormone concentrations (corticosterone) in a songbird, the great tit (Parus major). Adults nesting in white-light transects had higher corticosterone concentrations than in the other treatments. We also found a significant interaction between distance to the closest lamppost and treatment type: individuals in red light had higher corticosterone levels when they nested closer to the lamppost than individuals nesting farther away, a decline not observed in the green or dark treatment. Individuals with high corticosterone levels had fewer fledglings, irrespective of treatment. These results show that artificial light can induce changes in individual hormonal phenotype. As these effects vary considerably with light spectrum, it opens the possibility to mitigate these effects by selecting street lighting of specific spectra.

Keywords: corticosterone, stress, Parus major, great tit, artificial light, light spectra

1. Introduction

The night-time environment has changed dramatically since the invention of electric lighting [1]. However, light pollution is an overlooked disruptor of natural habitats that also perturbs individual physiological processes that rely on precise light information [2]. Artificial illumination at night impacts animal populations by disrupting orientation [3], reproduction [4], and by changing predation and competition pressures [5]. The repercussions of these behavioural and physiological changes in natural systems remain largely unknown and constitute a new and relevant focus for ecological research [6]. To illustrate, we are unaware of studies that look at the effects of experimental nocturnal light on stress physiology in free-living animals (see [7] for reproductive physiology), even though understanding these physiological effects is essential for developing measures to reduce potential impacts.

The concentrations of glucocorticoids (corticosterone in birds) are often taken as a direct measurement of the allostatic demand an animal experiences [8]. In the laboratory, rats exposed to constant white light had both elevated baseline corticosterone concentrations and non-normal, arrhythmic corticosterone release [9]. By contrast, light treatment of captive perch showed no effect on cortisol levels [10]. City planners might be able to mitigate disruptive effects of light pollution if certain wavelengths caused less perturbation than others, as long wavelengths (e.g. red) may have stronger photostimulation in birds than short wavelengths (e.g. blue). For example, a laboratory study in buntings found that red, but not blue, light advanced gonadal growth [11]. However, the physiological impacts of different spectra on free-living animals are completely unknown.

Here, we made use of an experimental set-up to assess the effects of artificial night light of different spectra on stress physiology in a free-living songbird, the great tit (Parus major). We hypothesized (based on information from laboratory studies [9,12]) that birds nesting in light treatments, specifically in red and white, will have higher baseline corticosterone concentrations than in other treatments and that the effects on hormone levels are stronger for individuals nesting closer to the lampposts.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study sites and standard protocols

We illuminated eight previously dark natural areas with street lamps (8.2 ± 0.3 lux) from sunset until sunrise. Each site contained four, 100 m-long transects with five 4 m tall lampposts; each transect emanating either LED light (red, white or green) or no light as a dark control treatment [13]. The order of the transects was randomly assigned per site. Briefly, the green lamps have less red and more blue light, and the red lamps have less blue and more red light. As these spectra are eventually intended for civil use, light levels are normalized to lux at our experimental sites. Nine nest-boxes were placed in each transect ([14]; 39% box occupancy). Adults were caught in the nest-box between 09.00 and 15.00 and between day 10 and 12 of chick rearing using a spring trap. Blood samples were collected well within 3 min (mean ± s.e.: 1.1 ± 0.2 min) and placed on ice. They were spun within 5 h for 10 min at 16 000g, and plasma was frozen at −20°C until analysis.

(b). Hormone analysis

We determined plasma corticosterone concentrations using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Cat. No. 901-097, Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI), following a double diethylether extraction of 7 µl plasma. Samples, a buffer blank and two standards (20 ng ml−1) were then re-dissolved in 280 µl of assay buffer (1 : 40 dilution) and allowed to reconstitute overnight [15]. One hundred microlitres of each sample (in duplicate) were then added randomly to individual wells on an assay plate. Buffer blanks were below the assay's lower detection limit (0.033 ng ml−1). The average intra-plate coefficient of variation was 3.2% and the inter-plate coefficient of variation was 9.4% (n = 5 plates).

(c). Statistical analyses

Statistical tests were performed in R, v. 3.1.2 (R Development Core Team 2011). We ran linear mixed models (LMM) to test if corticosterone levels were affected by the interaction between treatment (red, green, white and dark) and location of the nest (distance to the closest lamppost) with the following covariates to control for other factors that may have an effect on endogenous corticosterone levels: capture date, brood size, body mass and sex. We log-transformed corticosterone levels so that model assumptions were met. Capture time had no effect on corticosterone levels (t = 1.34, d.f. = 236, p = 0.18) and remained insignificant in all models, so we did not include this variable in the final analysis. Site and nest-box ID (nested within transect) were included as random effects to control for possible site effects and interactions between male and female within a pair and common environmental effects. We tested if corticosterone levels differed by treatment and the interaction term with a Tukey post hoc test. To test if corticosterone and light treatment with distance had an effect on the number of fledglings, we compared reproductive success in a two-step way as the distribution of the number of fledged chicks was zero-inflated. First, we analysed the probability of brood failure (1 = at least one chick fledged; 0 = no chicks fledged) in a GLMM with binomial errors. Second, we analysed the number of chicks fledged excluding brood failures in a LMM with site and nest-box ID as random variables.

3. Results

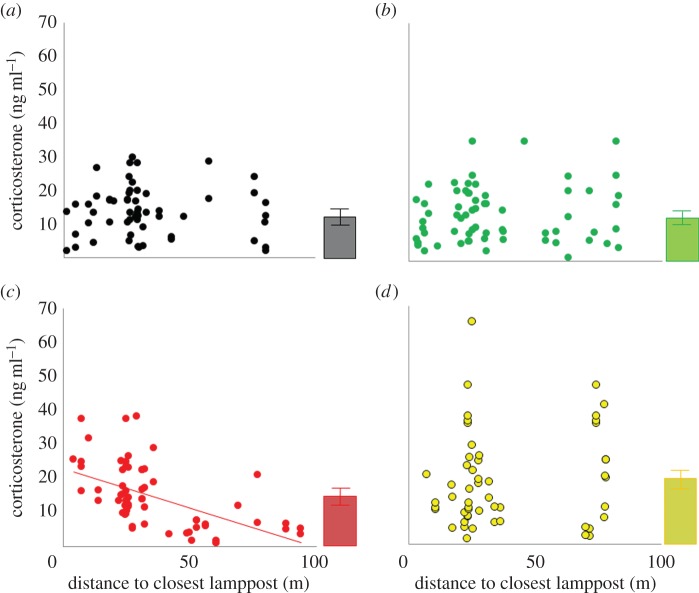

There was a significant effect of treatment and the interaction of treatment and distance to the closest lamppost on corticosterone levels (table 1 and figure 1). The post hoc test for the main effect (treatment) showed that birds breeding in the white treatment (mean ± s.e.: 18.7 ± 1.8 ng ml−1) had significantly higher corticosterone levels than in the dark (13.7 ± 0.9 ng ml−1; p = 0.04) and the green (13.6 ± 1.0 ng ml−1; p = 0.03), but not the red (15.4 ± 1.1 ng ml−1; p > 0.2) treatments (figure 1). Individuals nesting closer to the lampposts in the red treatment had higher corticosterone than individuals nesting farther away (t = −2.6, p = 0.008). Post hoc tests of the interaction term showed a significant effect of distance to lamppost on corticosterone levels in red light (slope was more negative) compared to green light (estimate = 0.69, s.e. = 0.23, z = 2.999, p = 0.01) and the dark treatment (estimate = 0.60, s.e. = 0.24, z = 2.51, p = 0.05), but no difference to the white treatment (p > 0.3). The number of young within a nest was positively related to corticosterone levels (table 1).

Table 1.

Model estimates to test the effect of light treatment on corticosterone levels. The p-values for treatment and the interaction term were calculated according to Kenward–Roger approximation [16]. Individual estimates are given from summary statistics of the LMM (d.f. = 219, log likelihood: −240.7).

| variable | d.f. | F | estimate | s.e. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment | 3, 67.9 | 2.31 | 0.029 | |||

| dark (N = 57) | 1.61 | 1.24 | ||||

| green (N = 64) | 1.61 | 1.23 | ||||

| red (N = 66) | 2.12 | 1.25 | ||||

| white (N = 53) | 1.81 | 1.20 | ||||

| treatment : distance to lamppost | 3, 65.7 | 3.18 | 0.017 | |||

| dark: distance to lamppost | −0.005 | 0.004 | ||||

| green: distance to lamppost | −0.007 | 0.003 | ||||

| red: distance to lamppost | −0.010 | 0.003 | ||||

| white: distance to lamppost | 0.001 | 0.003 | ||||

| brood size | 1, 139 | 3.88 | 0.009 | |||

| capture date | 1, 149 | 0.46 | 0.496 | |||

| body mass | 1, 149 | 0.09 | 0.801 | |||

| sex | 1, 139 | 0.08 | 0.781 |

Figure 1.

Corticosterone levels according to light treatment: (a) dark, (b) green, (c) red and (d) white versus nest-box distance to the closest lamppost. A regression line is shown when the interaction between distance and treatment was significant in the model. Means ± 1 s.e. of corticosterone levels for each treatment are at the side of each panel. (Online version in colour.)

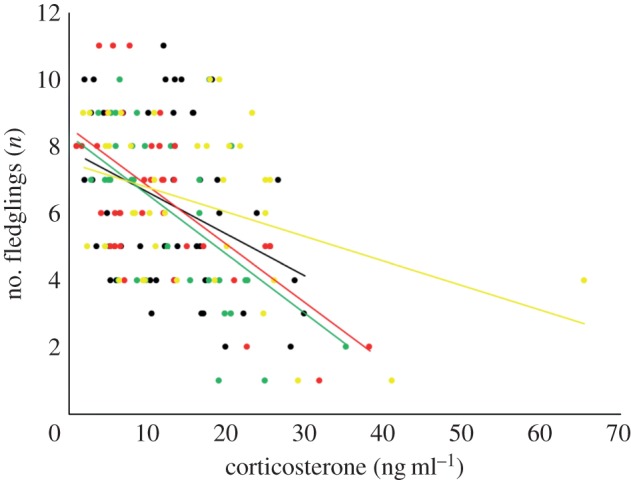

The probability to successfully fledge at least one young was not related to corticosterone levels, treatment or treatment and distance interactions (all p > 0.3; corticosteronered-failed = 18.02 ± 4.0, corticosteronedark-failed = 2.9, corticosteronegreen-failed = 8.9 ± 3.0, corticosteronewhite-failed = 39.2 ± 2.6). When we excluded failed broods from the analysis, individuals with higher corticosterone concentrations fledged fewer offspring than individuals with lower concentrations (coef. = −0.70, s.e. = 0.29, t = −2.442, p = 0.02), but the number of fledglings was not related to treatment and distance interaction (p > 0.2; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of fledglings produced versus individual corticosterone concentrations with light treatments. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

We assessed the effects of different light spectra on corticosterone concentrations in free-living adult great tits during the breeding season. We found that individuals nesting in white light had higher corticosterone levels than individuals nesting in green light or dark control. Moreover, individuals nesting closer to the lamppost in red light had higher corticosterone levels than individuals nesting farther away, differing from the effect of distance in dark and green treatments.

The magnitude of increase in corticosterone levels in free-living songbirds exposed to white light resembles that of the laboratory study on rats [9]. Even though light intensity used in the laboratory was much higher than in our study and the rats were not able to move away from the light, we still found similar effects of white light on corticosterone levels in free-living animals. Such elevated corticosterone concentrations could be due to sleep disturbance or restlessness [17] or to alterations in circadian rhythms in lit areas [7]. If light caused individuals to alter the phase angle of their circadian rhythm, it is likely that corticosterone levels, which typically change on a diel basis [18], will change as well. Indirectly, corticosterone levels could have been elevated as a result of increased metabolism due to increased food availability and parental feeding rates [19]. Note that corticosterone levels of some individuals under white light were within the stress-induced range for individuals that experience a capture restraint stressor [20], which suggests that these individuals could be experiencing stressors, e.g. increased levels of predation.

Individual corticosterone levels decreased with distance to the lamppost in red light. Moreover, while the effect of distance in red light was different from dark and green, it was not different from that in white light. Birds may perceive red light as being less intense than other colours [21], such that the effect diminishes quicker with distance. Across treatment groups, high corticosterone levels were correlated with lower fledgling numbers, which could be due to effects of narrow-wavelength light on chick development [20]. We did not detect a differential effect of spectra on reproductive success; such effects could have been masked by environmental conditions or other indirect effects on fitness [14]. We note that although this study is experimental in design, we still could not assign individuals randomly to treatment groups. Thus, any differences we observed could be due to differential settlement, although we did not detect any morphological differences between birds in different treatments or distances [14].

In our study of a free-living species, individuals were able to move away from possible harmful, direct effects of light. Even so, great tits nesting in white light had high corticosterone levels. As a first experimental test of the effects of light at night on stress hormones in free-living individuals, we show that the internal mechanisms are affected differently by different light spectra. Whether such effects are due to indirect or direct consequences of artificial light at night is currently unknown, but our results do open up the possibility of mitigating potential physiological change by using different spectra for street lights.

Acknowledgements

We thank Staatsbosbeheer, Natuurmonumenten, the Dutch Ministry of Defence and Het Drentse Landschap for allowing us to illuminate natural habitat and to work in their terrain. We thank Koosje Lamers, Sofia Scheltinga and Helen Schepp for field assistance.

Ethics

This study was carried out with the approval of the Animal Experimentation Committee of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Data accessibility

Data from the manuscript can be found in Dryad doi:10.5061/dryad.v2890.

Authors' contributions

J.Q.O. and M.J. collected the data, and M.H. coordinated the hormone analysis. K.S., R.G., M.E.V. conceived and set up the field sites. J.Q.O. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in experimental design, analysis input and manuscript revisions.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

The set-up and maintenance of the research sites is financed by the Dutch Technology Foundation STW, part of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). The project is supported by Philips and the Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij (NAM). J.Q.O. is supported by a NSF postdoctoral fellowship in biology (DBI-1306025).

References

- 1.Cinzano P, Falchi F. 2014. Quantifying light pollution. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 139, 13–20. ( 10.1016/j.jqsrt.2013.11.020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navara KJ, Nelson RJ. 2007. The dark side of light at night: physiological, epidemiological, and ecological consequences. J. Pineal. Res. 43, 215–224. ( 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00473.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salmon M. 2003. Artificial night lighting and sea turtles. Biologist 50, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Geffen KG, van Eck E, de Boer RA, van Grunsven RHA, Salis L, Berendse F, Veenendaal EM. 2015. Artificial light at night inhibits mating in a Geometrid moth. Insect Conserv. Divers. 8, 282–287. ( 10.1111/icad.12116) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blake D, Hutson AM, Racey PA, Rydell J, Speakman JR. 1994. Use of lamplit roads by foraging bats in southern England. J. Zool. 234, 453–462. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb04859.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rich C, Longcore T. 2006. Ecological consequences of artificial night lighting. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dominoni DM, Helm B, Lehmann M, Dowse HB, Partecke J. 2013. Clocks for the city: circadian differences between forest and city songbirds. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20130593 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.0593) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofer H, East ML. 1998. Biological conservation and stress. Stress Behav. 27, 405–525. ( 10.1016/S0065-3454(08)60370-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheving L, Pauly J. 1966. Effect of light on corticosterone levels in plasma of rats. Am. J. Physiol. 210, 1112–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brüning A, Hölker F, Franke S, Preuer T, Kloas W. 2015. Spotlight on fish: light pollution affects circadian rhythms of European perch but does not cause stress. Sci. Total Environ. 511, 516–522. ( 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.12.094) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar V, Rani S, Malik S. 2000. Wavelength of light mimics the effects of the duration and intensity of a long photoperiod in stimulation of gonadal responses in the male blackheaded bunting (Emberiza melanocephala). Curr. Sci. 79, 508–510. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oishi T, Lauber JK. 1973. Photoreception in the photosexual response of quail. II. Effects of light intensity and wavelength. Am. J. Physiol. 225, 880–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spoelstra K, van Grunsven RHA, Donners M, Gienapp P, Huigens ME, Slaterus R, Berendse F, Visser ME, Veenendaal E. 2015. Experimental illumination of natural habitat—an experimental set-up to assess the direct and indirect ecological consequences of artificial light of different spectral composition. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20140129 ( 10.1098/rstb.2014.0129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Jong M, Ouyang JQ, Da Silva A, van Grunsven RHA, Kempenaers B, Visser ME, Spoelstra K. 2015. Effects of nocturnal illumination on life-history decisions and fitness in two wild songbird species. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20140128 ( 10.1098/rstb.2014.0128) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouyang JQ, Hau M, Bonier F. 2011. Within seasons and among years: when are corticosterone levels repeatable? Horm. Behav. 60, 559–564. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.08.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halekoh U, Højsgaard S. 2011. A Kenward–Roger approximation and parametric bootstrap methods for tests in linear mixed models—the R Package pbkrtest. J. Stat. Soft. 59, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouyang, et al. In preparation. Nocturnal disturbance and physiological consequences of living under artificial night light. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rich EL, Romero LM. 2001. Daily and photoperiod variations of basal and stress-induced corticosterone concentrations in house sparrows (Passer domesticus). J. Comp. Physiol. B 171, 543–547. ( 10.1007/s003600100204) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Titulaer M, Spoelstra K, Lange CYMJG, Visser ME. 2012. Activity patterns during food provisioning are affected by artificial light in free-living great tits (Parus major). PLoS ONE 7, e37377 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0037377) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouyang JQ, Sharp P, Quetting M, Hau M. 2013. Endocrine phenotype, reproductive success and survival in the great tit, Parus major. J. Evol. Biol. 26, 1988–1998. ( 10.1111/jeb.12202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis PD, Morris TR. 2000. Poultry and coloured light. Poult. Sci. 56, 189–207. ( 10.1079/WPS20000015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the manuscript can be found in Dryad doi:10.5061/dryad.v2890.