Abstract

Background

Biliary cystic tumours (BCT) [biliary cystadenoma (BCA) and cystadenocarcinoma (BCAC)] warrant complete resection. Simple liver cysts (SLC) require fenestration when symptomatic. Distinguishing between BCT and atypical SLC with pre-operative imaging is not well studied.

Methods

All patients undergoing surgery for a pre-operative suspected SLC or BCT between 1992 and 2014 were included. Peri-operative data were retrospectively reviewed. A blind radiological review of pre-operative imaging was performed.

Results

Ninety-four patients underwent fenestration (n = 54) or complete excision (n = 40). Final pathology was SLC (n = 74), BCA (n = 15), BCAC (n = 2) and other primary malignancies (n = 3). A frozen section (FS) was performed in 36 patients, impacting management in 10 (27.8%) by avoiding (n = 1) or mandating a liver resection (n = 9). Frozen section results were always concordant with final pathology. Upon blind review, a solitary lesion, suspicious intracystic component, septation and biliary dilatation were associated with BCT (P < 0.05). Diagnostic sensitivity was high (87.5–100%) but specificity was poor (43.1–53.4%). The diagnostic value of imaging was most accurate when negative for BCT (negative predictive value: 92.5–100%).

Conclusion

Radiological assessment of hepatic cysts is relatively inaccurate as SLC frequently present with concerning features. In the absence of a strong suspicion of malignancy, fenestration and FS should be considered prior to a complete resection.

Introduction

Biliary cystic tumours (BCT), subdivided into biliary cystadenoma (BCA) and cystadenocarcinoma (BCAC), represent less than 5% of all hepatic cystic lesions.1 The prevalence of liver cysts in the general population is estimated at roughly 20%, and the incidence is rising. This is probably related to the increased use of abdominal cross-sectional imaging as a common diagnostic tool.2,3 The principle differential diagnosis for BCT, once infectious and metastatic liver lesions have been ruled out, is atypical-appearing simple liver cysts (SLC). To date, several clinical and radiological ‘worrisome features’ have been reported but do not provide reliable diagnostic differentiation between SLC and BCT or between BCA and BCAC.4–9 The benefit of pre-operative cyst fluid analysis is not used routinely, and its benefits are currently being debated.5,10 Accurately differentiating between BCT and SLC is critical because the management differs according to the diagnosis. SLC have no malignant potential and only require surgical treatment when symptomatic; typically consisting of laparoscopic fenestration. In contrast, BCT warrants a complete resection owing to their malignant potential and their high recurrence rate, ranging from 48.6% to 59.1% in cases of incomplete resection.9,11,12 Distinguishing between BCT and SLC with pre-operative imaging remains challenging, and an inaccurate pre-operative diagnosis can lead to inappropriate management such as unnecessary liver resections for SLC or fenestrations for BCT.

The present study sought to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of pre-operative imaging of patients surgically evaluated for SLC or BCT. Additionally, the impact of an intra-operative frozen section (FS) on management and outcomes was analysed.

Patients and methods

Patient population

A waiver of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization was obtained through Institutional Review Board approval. Data from patients undergoing liver surgery at our institution from January 1992 to January 2014 for any pre-operatively suspected occurrence of SLC, BCA or BCAC were collected from our prospectively maintained liver resection database. A pre-operative diagnosis of SLC was mainly based on the exclusion of other pathological entities. Surgical management was considered for symptomatic cysts or those felt to be suspicious for BCT. The operative approach was individualized according to the attending surgeon.

Clinical data

Clinical and demographic data were collected from the database and supplemented by a review of the medical records. The time interval from the first diagnosis of a liver cyst to surgery and reasons for surgery were collected. Symptoms at the time of surgery, as well as liver function tests and tumour markers, were also recorded. A pre-operative diagnosis was obtained from available notes from clinic and operative reports. Data on the surgical approach, extent of surgery and post-operative outcomes were collected. Surgery was classified as follows: fenestration, enucleation or a liver resection. A liver resection of three or more segments was defined as a major resection. Intra-operative FS was performed at the discretion of the treating surgeon and its impact on management was recorded. Morbidity was recorded in the Memorial Sloan Kettering Secondary Surgical Events program database using a grading system consistent with the ‘Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.0’.13 Cyst recurrence at last follow-up and management were documented.

Radiological review

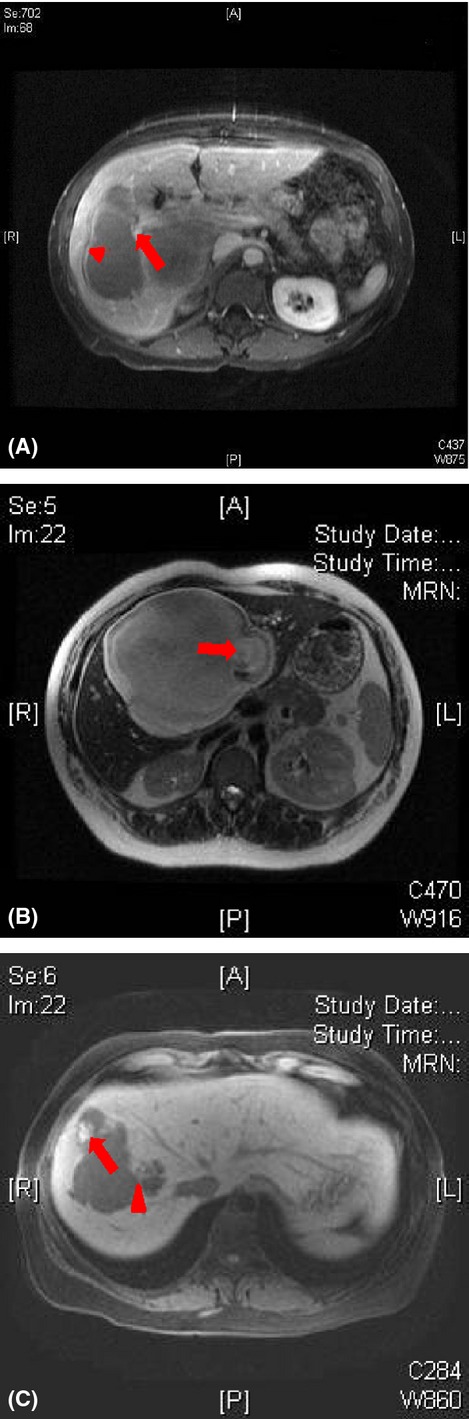

Pre-operative imaging including ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed within 3 months of surgery. These imaging studies were performed at outside institutions and/or MSKCC and were reviewed by two radiologists (S.G. and J.G.) blinded to all clinical and pathological data. Reviewers excluded suboptimal imaging studies, such as US without Doppler and CT or MRI without intravenous contrast. Images were reviewed specifically for the following features: size, solitary/multiple cysts thickness of cyst walls, septations, intracystic component, intrahepatic biliary dilatation and portal lymphadenopathy. Each radiological feature, if present, was evaluated for findings potentially consistent with BCT based on the following definitions. A cyst wall was defined as suspicious if enhancing and thicker than 2 mm or contained mural nodules. Septations were deemed suspicious if thicker than 3 mm or nodular.14 A worrisome intra-cystic component was defined as any intra-cystic solid-like component with features such as having a size larger than 10 mm with enhancement, calcifications or papillary projections. The intrahepatic bile duct was defined as dilated when its diameter was greater than 2 mm. Lymph nodes were deemed suspicious when measured larger than 10 mm in the short axis. Based on all available imaging and using these criteria, reviewers recorded their suspected diagnosis for each patient. Examples of suspicious radiological features are provided in Fig.1.

Figure 1.

Suspicious cyst characteristics. (a) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T2 post contrast. Biliary cystadenoma with a suspicious cyst wall (arrow) and suspicious septation (arrowhead). (b) MRI T1. Biliary cystadenoma with a suspicious intracystic component (arrow). (c) MRI T2 pre contrast. Simple liver cyst with a suspicious intracystic component (arrow) and septation (arrowhead)

Final diagnosis

The pathological criteria for BCT were similar to the latest World Health Organization definition.15 BCA was defined as a (i) cystic neoplasm, (ii) without bile duct communication, (iii) with cuboidal to columnar, variably mucin-producing epithelium and (iv) mesenchymal ‘ovarian-like’ stroma. If any invasive carcinoma was identified, the lesion was denoted as a BCAC. SLC was defined as a cystic lesion lined by a thin wall consisting of cuboidal epithelium with underlying fibrous stroma. Agreement between the intra-operative FS diagnosis and final pathology was assessed. The presence of dysplasia, the margin status after enucleation or resection, and the pathology of underlying non-cystic liver parenchyma were recorded when available.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized using percentages and continuous variables were summarized using the median (range). Characteristics of patients were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables to determine statistically significant differences between SLC and BCT. The diagnostic accuracy of each reviewer was assessed using sensitivity and specificity calculation. Inter-reviewer agreement was evaluated using a Kappa–Cohen test.16,17 All P-values were based on two-tailed statistical analysis and a P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Descriptive data

From 1992 through to 2014, 3534 patients underwent liver surgery at our institution, of which 94 (2.3%) were for one or more hepatic cystic lesions pre-operatively diagnosed as SLC or BCT. Baseline characteristics are listed in Table1. Most patients were female (83%) and about two-thirds were symptomatic at presentation (64.9%). The median interval between diagnosis and surgery was 4 months (0–354). An initial conservative approach with regular monitoring before surgery was adopted in 24 patients. The reasons for such an approach was a suspected SLC, for which a patient was initially asymptomatic (n = 22) or declining surgery (n = 2). In this group, the median interval between diagnosis and surgery was 50 months (range, 5–354). Pre-operative cyst fluid aspiration was performed in 12 symptomatic patients and was combined with concomitant tumour marker levels and cytology in 4 patients. Cytology was positive in one patient who had a final diagnosis of BCAC. On pre-operative imaging, the median tumour size was 11.1 cm (range, 2–30). The cyst was noted to be located in the right lobe (47.9%), left lobe (35.1%) or centrally (17%).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients with simple liver cysts and biliary cystic tumours

| Total (n = 94) | SLC (n = 74) | BCT (n = 20) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 62 (23–86) | 56 (23–74) | 64 (35–86) | 0.002 |

| Female, n (%) | 78 (83%) | 61 (82.4%) | 17 (85%) | 1 |

| BMI (n = 44) | 27.4 (18–77) | 27.7 (18–43) | 26.8 (22–55) | 0.9 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | 61 (64.9%) | 50 (67.6%) | 11 (55%) | 0.313 |

| Pain | 52 (85.2%) | 42 (84%) | 10 (91%) | |

| Weight Loss | 3 (4.9%) | 3 (6%) | – | |

| Jaundice | 2 (3.3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (9%) | |

| Respiratory symptoms | 4 (6.6%) | 4 (8%) | – | |

| Pre-operative laboratory data | ||||

| AST (U/l) (n = 78) | 26.5 (9–135) | 24 (9–135) | 27 (17–41) | 0.298 |

| ALT (U/l) (n = 78) | 26 (12–186) | 24 (12–186) | 31.5 (14–87) | 0.224 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) (n = 79) | 0.5 (0.2–4.9) | 0.5 (0.2–2.9) | 0.6 (0.3–4.9) | 0.83 |

| CA 19-9 (U/ml) (n = 23) | 26 (1–495) | 20.8 (1–495) | 47.5 (8–67) | 0.236 |

| CEA (ng/ml) (n = 30) | 1.5 (0.1–72) | 1.4 (0.1–7) | 2.2 (1–72) | 0.381 |

Bold variables are those which were significantly associated with BCT.

Values are presented as median (range) unless otherwise specified.

Operative data and outcomes

Intra-operative and pathology data

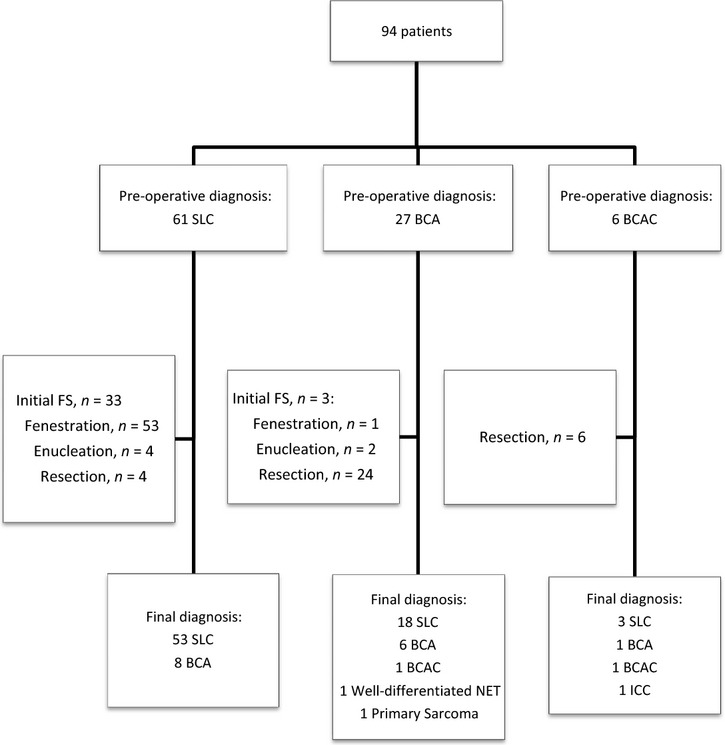

The pre-operative and final diagnoses are summarized in Fig.2. The overall discrepancy rate between pre-operative and final diagnoses was 30.9% (n = 29). Eight patients (40%) with BCT were pre-operatively misdiagnosed as SLC, whereas 21 patients with a final diagnosis of SLC (28%) were initially misdiagnosed as BCT. Fifty-four patients underwent cyst fenestration, all for SLC. A complete resection consisted of enucleation (n = 6) and a liver resection (n = 34), of which 20 patients had SLC. A major hepatectomy was performed on 13 patients (four with SLC). An extrahepatic resection was carried out on three patients (a common bile duct resection in one patient with BCA, a diaphragm resection and a transverse colectomy in two patients with SLC). A laparoscopic approach was used in 47 patients, mainly for cyst fenestration (n = 44, 94%). Omentoplasty was combined with a fenestration in 13 cases, enucleation in five and a liver resection in two. There was no mortality within 90 days. The major morbidity rate was 6.4%. All patients who underwent a formal liver resection had completely negative margins at final pathology. In 34% of cases, SLC was reported as complicated by an intracystic haemorrhage either at the time of fenestration or pathology.

Figure 2.

Management flow-chart of 94 patients with intrahepatic cystic lesions. BCA, biliary cystadenoma; BCAC, biliary cystadenocarcinoma; FS, frozen section; ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; NET, neuroendocrine tumour; SLC, simple liver cyst

Frozen section

Intra-operative FS was performed in 36 cases (38%). Twenty-one (58%) of these 36 operations were performed laparoscopically. FS influenced surgical management in 10 patients (28%). Nine patients were converted from fenestration to a complete cyst resection after being diagnosed with BCT. In one patient, a liver resection was avoided by diagnosing an SLC. In all cases, an FS and final pathological diagnosis were concordant.

Outcomes

After a median follow-up of 39 months (range, 1–188), 13 patients (13.8%) experienced liver cyst recurrence. Eleven patients with SLC treated with fenestration (20.3%) developed a cyst recurrence, of which two were symptomatic at 82 and 188 months after surgery, respectively. One patient with BCAC treated with a resection recurred in the liver after 8 months. One patient with a cystic primary liver sarcoma recurred in the lung and the liver after 6 months. Both of these patients with malignancy died within 12 months of surgery. No patients with BCA (n = 15) died or experienced recurrence after a median follow-up of 43.8 months (range, 1–180). Of note, eight patients with BCA and one with BCAC had intra-operative FS of a fenestration specimen before complete resection. None of these patients has recurred after a median follow-up of 16 months (range 12–83).

Clinical and radiological characteristics associated with BCT

Clinical and biological characteristics

A comparison between patients with SLC (n = 74) and with BCT (n = 20) is shown in Table1. Patients resected for BCT were significantly younger (median 56 versus 64 years, P = 0.002). Most patients with BCT and SLC were female (85%) which was not statistically different between the groups. Elevated serum liver enzymes or serum tumour markers levels were not associated with BCT.

Radiological characteristics

Retrospective review of imaging reports

Reports of 204 imaging studies (80 US, 70 CT, 54 MRI) from 94 patients were reviewed. BCT was significantly associated with a solitary cyst (n = 16; 80% versus n = 25; 33.8%; P = 0.001). Similarly, BCT was associated with the presence of an intracystic solid component (n = 5; 25% versus n = 6; 8.1%; P = 0.03) and tended to be associated with mural nodules (n = 6; 30% versus n = 11; 14.9%; P = 0.09) and septations (n = 12; 60% versus n = 28; 37.8%; P = 0.07). Features such as the presence or absence of biliary dilatation and portal lymph nodes and estimations of wall thickness, septation thickness and intracystic component size were not available in every report and could not be included in the analysis.

Blinded imaging review

Twenty patients (SLC, n = 15; BCA, n = 4; BCAC, n = 1) who had no available or suitable pre-operative imaging performed within 3 months of surgery were excluded. Overall, 74 patients (SLC, n = 57; BCA, n = 13; BCAC, n = 1, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, n = 1, primary sarcoma, n = 1, neuroendocrine tumour, n = 1) with 136 imaging studies were reviewed. Twenty-six patients had one imaging modality (US, n = 7; CT, n = 10; MRI, n = 9) and 34 had two pre-operative imaging modalities (US+CT, n = 18; US+MRI, n = 13; CT+MRI, n = 3). Fourteen patients underwent pre-operative US, CT and MRI. Inter-reviewer agreement was moderate (Kappa–Cohen index = 0.49; 95%CI 0.29–0.69, P < 0.001). When considering the final blinded radiological diagnosis, accuracy varied between reviewers (Table2). The sensitivity for BCT diagnosis ranged from 87.5% to 100%. All malignant cases (n = 4) were identified by both reviewers. There was a trend towards an improved sensitivity with the number of imaging modalities, from 80% in patients with one imaging modality to 100% in patients with two or three imaging modalities. In contrast, specificity for BCT diagnosis was low, ranging from 43.1 to 53.4%, resulting in a high-false positive rate for BCT (36.5–44.6%). This finding was emphasized by the low positive predictive value of imaging (29.8–37.2%) and the high negative predictive value (92.5–100%) for BCT. Of particular note, diagnostic accuracy was not influenced by the study period (Table3). In other words, imaging provided a reliable diagnostic result when negative for BCT but was inaccurate when interpreted as positive or suggestive for BCT.

Table 2.

Radiological characteristics according to imaging review

| Final diagnosis | Reviewer 1 | Reviewer 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 74 | SLC (n = 58) | BCT (n = 16) | P | n = 74 | SLC (n = 58) | BCT (n = 16) | P | |

| Size, cm | 11.3 (2–30) | 10.7 (2–30) | 9.8 (3.6–22) | 0.641 | 11.8 (2–30) | 10.9 (2–30) | 9.9 (3.6–22) | 0.441 |

| Side | ||||||||

| Right | 38 (51.4%) | 32 (55.2%) | 6 (37.5%) | 0.357 | 38 (51.4%) | 32 (55.2%) | 6 (37.5%) | 0.357 |

| Left | 26 (35.1%) | 18 (31%) | 8 (50%) | 26 (35.1%) | 18 (31%) | 8 (50%) | ||

| Central | 10 (13.5%) | 8 (13.8%) | 2 (12.5%) | 10 (13.5%) | 8 (13.8%) | 2 (12.5%) | ||

| Solitary | 31 (41.9%) | 20 (34.5%) | 11 (68.8%) | 0.021 | 31 (41.9%) | 20 (34.5%) | 11 (68.8%) | 0.021 |

| Suspicious wall | 48 (64.9%) | 33 (56.9%) | 15 (93.8%) | 0.007 | 60 (81.1%) | 45 (77.6%) | 15 (93.8%) | 0.277 |

| Septation | 61 (82.4%) | 45 (77.6%) | 16 (100%) | 0.058 | 59 (79.7%) | 43 (74.1%) | 16 (100%) | 0.031 |

| Suspicious septation | 29 (39.2%) | 21 (36.2%) | 8 (50%) | 0.317 | 40 (54.1%) | 28 (14.3%) | 12 (75%) | 0.088 |

| Suspicious intracystic component | 26 (35.1%) | 16 (27.6%) | 10 (62.5%) | 0.01 | 39 (52.7%) | 26 (44.8%) | 13 (81.3%) | 0.012 |

| IHBD | 27 (36.5%) | 17 (29.3%) | 10 (62.5%) | 0.015 | 22 (29.7%) | 13 (22.4%) | 9 (56.3%) | 0.009 |

| Suspicious LN | 1 (1.4%) | – | 1 (6.3%) | 0.216 | 1 (1.4%) | – | 1 (6.3%) | 0.216 |

| Radiology diagnosis | SLC (n = 25) | SLC (n = 2) | SLC (n = 31) | – | ||||

| BCT (n = 33) | BCT (n = 14) | BCT (n = 27) | BCT (n = 16) | |||||

Bold variables are those which were significantly associated with BCT.

BCT, biliary cystic tumour; IHBD, intrahepatic biliary dilatation; LN, lymph nodes; SLC, simple liver cyst.

Table 3.

Overtime diagnostic performances of imaging for biliary cystic tumour (BCT) based on radiological review in 74 patients

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | |

| Whole period (1992–2014) (n = 74) | 87.5% | 100% | 43.1% | 53.4% | 29.8% | 37.2% | 92.5% | 100% |

| 1992–2004 (n = 20) | 100% | 100% | 41.2% | 47% | 23% | 25% | 100% | 100% |

| 2004–2014 (n = 54) | 84.6% | 100% | 43.9% | 56% | 32.3% | 41.9% | 90% | 100% |

R1, Reviewer 1; R2, Reviewer 2.

By combining all reviewed data, solitary lesion, suspicious intracystic component and intrahepatic bile duct dilatation were features significantly associated with BCT according to both radiological reviews (Table2). The presence of septations was significantly associated with BCT according to one of the reviewers.

Discussion

Biliary cystic tumours are rare. Although SLC and BCT managements are completely different, SLC can mimic BCT on imaging. A reliable diagnosis is critical to ensure appropriate management. The present study shows that characterization of atypical intrahepatic cysts using imaging remains challenging. Thus, surgeons treating pre-operatively suspected SLC or BCT are faced with difficult management decisions while specific guidance from radiological studies may be absent.

The diagnostic sensitivity of imaging for identifying BCT in this study was high (87.5–100%), meaning that most BCT are identified with pre-operative imaging. Such a high sensitivity is as a result of suspicious imaging features that are present in most BCT. Based on a blinded radiological review, we found that features such as a solitary lesion, a suspicious intracystic component, intrahepatic biliary dilatation and the presence of septations were significantly associated with BCT. Hence, all these features might be considered as suggestive of BCT. However, septations were also present in approximately three-quarters of SLC and one-third of SLC was solitary or had a suspicious intracystic component. This lack of specificity of pre-operative imaging features for BCT accounted for the low positive predictive value of imaging (29.8–37.2%), which resulted in a high false-positive rate for BCT. The patients with SLC mimicking BCT are at risk for being over treated with a resection, theoretically exposing them to a higher risk of operative morbidity. These findings document that pre-operative imaging cannot reliably differentiate BCT and atypical SLC. When the lesion was not suggestive for BCT, meaning a cystic lesion without worrisome features, the diagnostic value of imaging was most accurate (negative predictive value: 92.5–100%).

Frozen section was performed in 36 patients. Few publications have reported cases where BCA was misinterpreted as SLC on FS.18,19 In the current series, there was concordance between FS diagnosis and a final diagnosis in all 36 cases. Notably, surgical management was altered to a complete resection correctly in nine patients initially planned for SLC fenestration. Given these results, it is not surprising that 20 patients ultimately proven to have SLC were initially suspected of having BCT and over treated with a liver resection. This situation could have been safely obviated in these patients with intra-operative FS. Intra-operative cyst fenestration and sampling in patients who may have BCT is controversial because of the theoretical risk of peritoneal spillage. In our series, FS in patients with BCT appeared to be safe with no cases of local or peritoneal recurrence (BCA, n = 8; BCAC, n = 1) after a median follow-up of 18 months (range; 1–83). Taken all together, these findings suggest that FS is a safe and accurate approach for atypical cystic lesions characterization. While these data are not definitive, it is still reasonable to avoid such a biopsy in a lesion highly suspicious for an invasive malignancy.

Baseline characteristics such as demographics, clinical presentation and laboratory values were also explored. Patients with BCT were significantly older than patients with SLC. Patients with BCA (n = 15) were overwhelmingly women (n = 14), middle-aged (median 50 years; range 23–69) and 53% were symptomatic at presentation (n = 8). However, 82% of patients with SLC were also women. In our series, all patients with pre-operatively suspected SLC went to surgery because of symptoms at presentation but 67.6% of actual SLC had symptoms at presentation. In contrast to previous reports, symptoms at presentation were not associated with BCT.7 Regarding pre-operative laboratory values, neither serum liver enzymes nor serum tumour markers levels such as CEA and CA19-9 were associated with BCT. Few studies suggest that cyst fluid analysis can help in distinguishing SLC from BCT, but available data are conflicting and such analysis is currently not warranted in clinical practice.5,10,20–23 In the present study, pre-operative cyst fluid analysis was performed in only four patients and could not be assessed for diagnostic utility.

Survival after liver surgery for BCT is usually prolonged. In the most extensive series, 5-year overall survival was 84.2% in a cohort of 221 patients with BCA and 27 with BCAC.9 In our current series, patients with BCA (n = 15) were all alive at a median follow-up of 18 months (range, 1–180). One patient was alive without evidence of disease 83 months after a BCAC resection. Another patient with BCAC experienced liver recurrence 6 months after a resection and died within 12 months of surgery.

Our findings have several limitations. First, this study was retrospective over a 22-year time period. While imaging quality has improved over time, diagnostic accuracy did not improve when the analysis was restricted to the last 10 years. Second, imaging studies were heterogeneous and not uniform for all patients. However, a blinded, radiological review provided an unbiased assessment of images in a standardized fashion using predefined criteria. Third, the presence of a mesenchymal ‘ovarian-like’ stroma is an established feature of BCT as stated in the latest WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system.15 Cysts composed of serous lining cells sitting on a basement membrane without a mesenchymal stroma can indeed happen. However, this variant is virtually always benign. Although, few series reported cystic lesions without such a stroma as BCT, we regard them as benign simple biliary cysts.9,11,19 Additionally, the sample size was small and very few patients had BCAC. This underscores the relative rarity of BCT and the difficulty in studying these tumours. Finally, most patients referred to our institution presented with complex and large cysts that may not be representative of other practices. Furthermore, by definition, the study only included patients who were selected to undergo a resection. Given this selection bias, our results likely best apply to patients presenting with atypical, simple liver cysts on imaging.

In conclusion, based on a blinded, radiological review, pre-operative imaging cannot accurately differentiate atypical SLC from BCT. Tissue sampling with cyst fenestration and FS is safe and accurate. In the absence of features indicating invasive malignancy, fenestration with tissue sampling and FS should be considered an appropriate treatment strategy for any patient with an atypical or symptomatic liver cyst.

Conflict interest

None declared.

Support

Alexandre Doussot received support from the French Association of Hepatobiliary Surgery and Transplantation (ACHBT) and from Université de Bourgogne.

References

- Soares KC, Arnaoutakis DJ, Kamel I, Anders R, Adams RB, Bauer TW, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the liver: biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortelé KJ, Ros PR. Cystic focal liver lesions in the adult: differential CT and MR imaging features. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am Inc. 2001;21:895–910. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.4.g01jl16895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrim ZI, Murchison JT. The prevalence of simple renal and hepatic cysts detected by spiral computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:626–629. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regev A, Reddy KR, Berho M, Sleeman D, Levi JU, Livingstone AS, et al. Large cystic lesions of the liver in adults: a 15-year experience in a tertiary center. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:36–45. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00865-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffron A, Rao S, Ferrario M, Abecassis M. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: role of cyst fluid analysis and surgical management in the laparoscopic era. Surgery. 2004;136:926–936. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teoh AYB, Ng SSM, Lee KF, Lai PBS. Biliary cystadenoma and other complicated cystic lesions of the liver: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. World J Surg. 2006;30:1560–1566. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JK, Kim SH, Lee SH, Park JK, Woo SM, Jeong JB, et al. Appropriate diagnosis of biliary cystic tumors: comparison with atypical hepatic simple cysts. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:989–996. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328337c971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Miao R, Liu H, Du X, Liu L, Lu X, et al. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: an experience of 30 cases. Dig Liver Dis Off J Ital Soc Gastroenterol Ital Assoc Study Liver. 2012;44:426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutakis DJ, Kim Y, Pulitano C, Zaydfudim V, Squires MH, Kooby D, et al. Management of biliary cystic tumors: a multi-institutional analysis of a rare liver tumor. Ann Surg. 2015;261:361–367. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks D, Voitot H, Paradis V, Belghiti J, Vilgrain V, Farges O. Intracystic concentrations of tumour markers for the diagnosis of cystic liver lesions: tumour markers for diagnosing cystic liver lesions. Br J Surg. 2014;101:408–416. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. A light microscopic and immunohistochemical study of 70 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:1078–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buetow PC, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, Ros PR, Devaney K, Goodman ZD, et al. Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: clinical-imaging-pathologic correlations with emphasis on the importance of ovarian stroma. Radiology. 1995;196:805–810. doi: 10.1148/radiology.196.3.7644647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, Clauser SB, Minasian LM, Dueck AC, et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute's patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju244. : dju244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, Benacerraf B, Benson CB, Brewster WR, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256:943–954. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman FT World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th edn. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. p. 417. , eds. ( p. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch DC, Landis JR, Higgins IT, Gilson JC, Jones RN. An application of kappa-type analyses to interobserver variation in classifying chest radiographs for pneumoconiosis. Stat Med. 1984;3:73–83. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780030109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansman MF, Ryan JA, Holmes JH, Hogan S, Lee FT, Kramer D, et al. Management and long-term follow-up of hepatic cysts. Am J Surg. 2001;181:404–410. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt DP, Henderson JM, Chmielewski E. Cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the liver: a single center experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:727–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JA, Scriven MW, Puntis MC, Jasani B, Williams GT. Elevated serum CA 19-9 levels in hepatobiliary cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma. Two case reports with immunohistochemical confirmation. Cancer. 1992;70:1841–1846. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921001)70:7<1841::aid-cncr2820700706>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logroño R, Rampy BA, Adegboyega PA. Fine needle aspiration cytology of hepatobiliary cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma. Cancer. 2002;96:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Takenaka K, Gion T, Fujiwara Y, Taguchi K, Kajiyama K, et al. Treatment strategy for patients with cystic lesions mimicking a liver tumor: a recent 10-year surgical experience in Japan. Arch Surg Chic Ill 1960. 1998;133:643–646. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.6.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HK, Lee JK, Lee KH, Lee KT, Rhee JC, Kim KH, et al. Differential diagnosis for intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and hepatic simple cyst: significance of cystic fluid analysis and radiologic findings. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:289–293. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b5c789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]