Abstract

Background

The prognostic value of CA19-9 in patients with pancreatic cancer (PC) treated with neoadjuvant therapy has not been well described.

Methods

Pre-treatment CA19-9 levels (with concomitant normal bilirubin level) in patients with localized PC were categorized as normal (≤35), low (36–200), moderate (201–1000), or high (>1000). Post-treatment CA19-9 was measured after neoadjuvant therapy, prior to surgery.

Results

Pre-treatment CA19-9 levels were evaluable in 235 patients, levels were normal in 60 (25%) patients, low in 78 (33%) patients, moderate in 69 (29%) and high in 28 (12%). After neoadjuvant therapy, post-treatment CA19-9 normalized (≤ 35) in 40 (51%) of the patients in the low group, 14 (21%) of the moderate and 5 (19%) of the high group (P < 0.001). Of the 235 patients, 168 (71%) completed all intended therapy including a pancreatectomy; 44 (73%), 62 (79%), 46 (67%) and 16 (57%) of the normal, low, moderate and high groups (P = 0.10). Among these 168 patients, the median overall survival was 38.4, 43.6, 44.7, 27.2 and 26.4 months for normal, low, moderate and high CA19-9 groups (log rank P = 0.72). Among resected patients, an elevated pre-treatment CA19-9 was of little prognostic value; instead, it was the CA19-9 response to neoadjuvant therapy that was prognostic [hazard ratio (HR): 1.80, P = 0.02].

Conclusions

Among patients who completed neoadjuvant therapy and surgery, pre-treatment CA19-9 obtained at the time of diagnosis was not predictive of overall survival, but normalization of post-treatment CA19-9 in response to neoadjuvant therapy was highly prognostic.

Introduction

In contrast to many other solid organ tumours, treatment sequencing for patients with localized pancreatic cancer (PC) remains highly controversial. A surgery-first strategy for patients who ostensibly appear to have localized disease with no radiographical evidence of metastases has yielded a 5-year survival of only 15%, a statistic that has changed little in over 30 years. 1,2 Systemic recurrence after a margin negative (R0) resection occurs in the majority of patients, and this observation supports the hypothesis that PC is a systemic disease, even in the absence of radiographical evidence of distant metastases.3–5 Significant advances in surgical technique and peri-operative management have dramatically reduced the 30-day mortality after PC resection to <2%. However, the morbidity of the surgical procedure coupled with the poor overall oncological outcomes have undoubtedly contributed to the nihilistic perceptions of the medical community, which may have resulted in the underuse of PC surgery. 1,6 To reverse the negative perception of the general medical community regarding the utility of PC surgery, meaningful progress is needed in both available treatments and the sequencing of such treatments.

Radiographical staging can only detect measurable disease, but blood-based biomarkers have the advantage of being disease specific, quantitative and facilitate cost-effective monitoring of treatment response. For PC, serum levels of a carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 has been extensively studied as a prognostic biomarker. High pre-treatment CA19-9 levels have been associated with poor prognosis in patients with resected PC, as well as in patients with advanced-stage disease who received chemotherapy.7–11 The outcomes of patients with a very high pre-operative CA19-9 (> 1000) who were treated with a surgery-first approach were particularly poor, prompting some clinicians to endorse a neoadjuvant strategy for this population.12 The rationale for using neoadjuvant therapy is obvious when systemic disease is suspected but not radiographically confirmed, as it allows for the immediate delivery of systemic therapy for the treatment of occult micrometastases. Patients who have an aggressive tumour biology and exhibit disease progression while on therapy can be identified prior to surgery and be spared an operation with limited oncological benefit. In addition, serial measurements of CA19-9 levels prior to therapy (pre-treatment) and after neoadjuvant therapy (post-treatment) may be correlated with the treatment response and survival and, thus, have an important clinical prognostic value. A decrease in CA19-9 in response to neoadjuvant therapy has previously been reported to correlate with overall survival in two series of patients with localized PC.13,14 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association of pre-treatment and post-treatment CA19-9 levels on the completion of neoadjuvant therapy, including surgery, and overall survival in patients with localized PC.

Patients and Methods

Study subjects

Using a prospectively maintained PC database at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW), we reviewed consecutive patients with resectable and borderline (BLR) PC who underwent neoadjuvant therapy (with surgical intent) for biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma of the pancreas from 2009 to 2014. Patients with other histologies and patients with PC who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy were excluded. Serum CA19-9 was measured at the author's institution and evaluated at two time points: prior to any neoadjuvant treatment (pre-treatment) and after neoadjuvant treatment was completed and prior to surgery (post-treatment). Pre-treatment and post-treatment CA19-9 values were considered evaluable if the value was identified when a concurrent serum total bilirubin value was less than 2 mg/dl. Patients without an evaluable pre-treatment CA19-9 were excluded. A CA19-9 cutpoint of 35 U/ml was used to dichotomize patients with normal (≤ 35) and elevated (> 35) values based on this institutional laboratory standard. Patients with an elevated CA19-9 were then further stratified into low (36–200), moderate (201–1000) and high (> 1000) groups.

The clinical stage at the time of diagnosis was determined using objective radiographical criteria based on computed tomography (CT) imaging to classify resectable or BLR disease.15 In addition, patients were also considered borderline resectable if: (i) there were radiographical findings indeterminate for metastatic disease, (ii) CA19-9 levels were > 2000 U/ml, or (iii) if the patient's baseline performance status was poor. The age-adjusted Charlson's comorbidity index (CCI) is a weighted index that takes into account the number and seriousness of the comorbid disease.16 The CCI was calculated by examining the electronic medical record for explicit documentation of the CCI comorbidity condition at the time of diagnosis/initial evaluation at our institution. This study was approved by the MCW Institutional Review Board.

Treatment

All patients received neoadjuvant therapy consisting of chemoradiation and/or chemotherapy, either on or off protocol. The majority of resectable patients received gemcitabine-based chemoradiation, and the majority of BLR patients received chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation. After the completion of neoadjuvant therapy, all patients underwent restaging with a physical examination, laboratory studies and CT imaging. Post-treatment CA19-9 levels were obtained 2–4 weeks after the completion of neoadjuvant therapy. To be considered for a pancreatectomy, patients were required to have: (i) the absence of metastatic disease; (ii) ≤ 180° tumour abutment of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or celiac artery, or short segment encasement of the hepatic artery; (iii) suitable SMV and PV to allow for venous reconstruction if necessary; and (iv) an acceptable operative risk based on performance status, physical examination and assessment of medical co-morbidities. Completion of all intended therapy was defined as the completion of neoadjuvant therapy and surgical resection of the PC. Our preferred surgical techniques for PD, distal pancreatectomy and total pancreatectomy have been previously described; a diagnostic laparoscopy was routinely performed before a laparotomy.17 The pancreatectomy specimen was evaluated as per the current AJCC pathology recommendations and the SMA margin of resection was considered positive (R1) if ink was present at the margin; the pancreatic transection margin and the hepatic duct margin were considered positive if a tumour was present on the final assessment of the margin.18 Post-operative complications were recorded from the database, verified in the electronic medical record and defined by the Clavien criteria.19 Any Clavien grade 3+ complication was considered a major complication. The length of hospital stay was calculated by including the day of operation and excluding the day of discharge. Readmission was defined as admission to any hospital within 30 days of surgery. The decision to recommend post-operative, adjuvant therapy was based on the opinion of the physician team and factors considered in this decision included: the length and duration of neoadjuvant therapy, the findings on permanent pathology of the resected specimen and the recovery of the patient. Adjuvant therapy was not recommended for all patients.

Surveillance

All patients underwent follow-up at 3- to 4-month intervals with a physical examination, laboratory studies and repeat CT imaging. In the event of recurrent PC, we recorded the date and location of recurrence and treatment. Recurrent disease was assessed radiographically; tissue confirmation of disease recurrence was rarely obtained. Disease-free survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of disease recurrence. Overall survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using Fischer's Exact test. All continuous variables were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Survival and follow-up was calculated from the time of initial diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Deaths from any cause were included in the survival analysis. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. We tested proportional hazard assumptions for all variables associated with survival. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and pre-treatment CA19-9

From 2009 to 2014, 252 patients were identified with resectable or BLR PC, who were treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Pre-treatment CA19-9 was not evaluable in 17 patients, and they were excluded. Of the remaining 235 evaluable patients, 99 (42%) had resectable, and 136 (58%) had BLR PC. The patient characteristics are summarized in Table1. Of the 235 patients, CA19-9 levels were normal in 60 (25%) and elevated in 175 (75%). Of the 60 patients with normal CA19-9, 2 (3%) had undetectable CA19-9 levels. The 175 patients included 78 (33%) in the low group, 69 (29%) in the moderate and 28 (12%) in the high subgroup. The median pre-treatment CA19-9 for all 235 patients was 119 [interquartile range (IQR): 487]; 14 (23), 79 (69), 488 (293) and 2297 (2350) for the normal, low, moderate and high groups, respectively (P < 0.001). No differences were observed in age, body mass index or Charlson's Comorbidity Indices between the subgroups.

Table 1.

Demographics and neoadjuvant treatment outcomes

| CA 19-9 category | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total n = 235 | Normal n = 60 | Low n = 78 | Moderate n = 69 | High n = 28 | P-value |

| Age, years median (IQR) | 65 (13) | 66 (14) | 65 (13) | 65 (12) | 62 (14) | 0.83 |

| Gender (Female), n (%) | 115 (49) | 36 (60) | 37 (47) | 32 (47) | 10 (36) | 0.16 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 25 (7) | 27 (8) | 25 (6) | 26 (8) | 26 (6) | 0.34 |

| Charlson's Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 4 (3) | 0.99 |

| Pre-treatment CA19-9, U/ml median (IQR) | 119 (487) | 14 (23) | 79 (69) | 488 (293) | 2297 (2350) | <0.001 |

| Post-treatment CA19-9, U/ml median (IQR) | 36 (102) | 9 (18) | 34 (44) | 107 (217) | 194 (423) | <0.001 |

| Elevated Post-treatment CA19-9, n (%) | 118 (51) | 4 (7) | 38 (49) | 54 (79) | 22 (81) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Stage, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Resectable | 99 (42) | 28 (47) | 43 (55) | 25 (36) | 3 (11) | |

| Borderline resectable | 136 (58) | 32 (53) | 35 (45) | 44 (64) | 25 (89) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy, n (%) | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | 42 (18) | 12 (20) | 11 (14) | 12 (17) | 7 (25) | 0.06 |

| Chemoradiation | 86 (37) | 21 (35) | 40 (51) | 20 (29) | 5 (18) | 0.001 |

| Both | 107 (45) | 27 (45) | 27 (35) | 37 (54) | 16 (57) | 0.07 |

| Completed Neoadjuvant and Surgery, n (%) | 168 (71) | 44 (73) | 62 (79) | 46 (67) | 16 (57) | 0.10 |

| Did not undergo pancreatectomy, n (%) | 0.77 | |||||

| Metastases | 50 (21) | 10 (17) | 12 (15) | 18 (26) | 10 (36) | 0.26 |

| Local disease progression | 4 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | – | 1 (4) | |

| Medical comorbidities | 12 (5) | 3 (5) | 3 (4) | 5 (7) | 1 (4) | |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 1 (2) | – | – | – | |

IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; CA, carbohydrate antigen.

Neoadjuvant therapy

Details of the neoadjuvant therapy administered are also summarized in Table1. Of the 235 patients, neoadjuvant therapy consisted of chemotherapy alone, chemoradiation alone, or both in 42 (18%), 86 (37%) and 107 (45%) patients, respectively. No significant differences in neoadjuvant treatment were observed between the normal, low and moderate pretreatment CA19-9 subgroups. However, in the high group, only 5 (18%) of the 28 patients received chemoradiation alone compared with the low group, where 40 (51%) of the 78 patients received chemoradiation alone (P = 0.009). Of the 99 patients with resectable PC, 67 (68%) received chemoradiation alone, 29 (29%) received chemotherapy alone and 3 (3%) received both. Of the 136 BLR patients, 104 (76%) received induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation, 19 (14%) received chemoradiation alone and 13 (10%) received chemotherapy alone.

Of all 235 patients, 168 (71%) completed all intended therapy to include successful surgery; 44 (73%), 62 (79%), 46 (67%) and 16 (57%) of the normal, low, moderate and high groups, respectively (P = 0.10). The most common reason why surgery was not completed was the development of metastatic disease progression discovered after neoadjuvant therapy that occurred in 50 (21%) of the 235 patients; 10 (17%), 12 (15%), 18 (26%) and 10 (36%) of the normal, low, moderate and high groups, respectively (P = 0.08). Local disease progression, which precluded resection, occurred in 4 (2%) of the 235 patients, all of whom had BLR disease. An additional 12 (5%) of the 235 patients had medical comorbidities that precluded a resection. One individual of advanced age (88 years old) elected not to pursue surgery after the completion of neoadjuvant therapy.

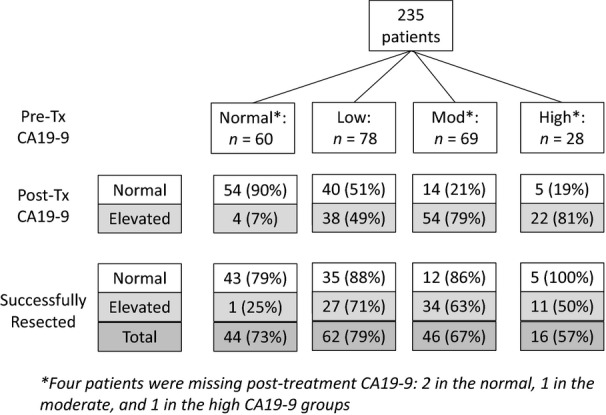

Post-treatment (pre-operative) CA19-9

Of the 235 patients, 231(98%) had an evaluable post-treatment CA19-9. Figure1 summarizes the changes in CA19-9 in response to neoadjuvant therapy. Overall, a significant decline in the CA19-9 level was observed after neoadjuvant therapy. The median post-treatment CA19-9 for all patients was 36 (IQR: 102); 9 (18), 34 (44), 107 (217) and 194 (423) for the normal, low, moderate and high groups, respectively (P < 0.001). A normal post-treatment CA19-9 was observed in 54 (93%); 40 (51%), 14 (21%) and 5 (19%) of the normal, low, moderate and high groups, respectively (P < 0.001). Interestingly, four patients with a normal pre-treatment CA19-9 developed an elevated post-treatment CA19-9; only one of these patients was resected, and the remaining three had metastatic disease when restaged after neoadjuvant therapy. Completion of all intended therapy to include a pancreatectomy was achieved in 95 (84%) of the 113 patients with a normal post-treatment CA19-9 compared with 73 (62%) of the 118 patients with an elevated post-treatment CA19-9 (P < 0.001). Of the 50 patients who developed metastatic disease after neoadjuvant therapy, 40 (80%) had an elevated post-treatment CA19-9 (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 response to neoadjuvant therapy

Peri-operative outcomes

No differences were observed in the operative procedures or peri-operative outcomes among the CA19-9 subgroups (Table2). Among the 168 patients who were resected, a pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) was the most common operation (n = 140, 83%). Venous resections/reconstructions were performed with 49 (29%) of the 168 pancreatectomies. No differences were observed in final (pathological) AJCC stage based on the pre-treatment CA19-9 group. Node positive disease was present in 55 (33%) of the 168 patients with a median of 25 (IQR: 13.5) lymph nodes examined per specimen. R0 resections were obtained in 165 (98%) of the 168 patients. Clavien grade 3 or higher post-operative complications occurred in 32 (20%) of the 168 patients. The median length of hospital stay was 9 days (IQR: 4), and 24 (14%) of the 168 patients were readmitted within 30 days. The 30-day mortality after a pancreatectomy was 1.2% (n = 2); after successful hospital discharge, one patient experienced an aspiration event that resulted in a cardiac arrest, anoxic brain injury and subsequent death, and the other patient had a sudden cardiac arrest after an uneventful operation on the day of surgery. Of the 168 patients who completed all intended neoadjuvant therapy and underwent resection of their pancreatic tumour, 86 (51%) received additional adjuvant therapy.

Table 2.

Operations and peri-operative outcomes

| Characteristic | Total N = 168 | Normal n = 44 | Low n = 62 | Moderate N = 46 | High N = 16 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation, n (%) | 0.30 | |||||

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 140 (83) | 36 (82) | 53 (85) | 37 (80) | 14 (88) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 21 (13) | 7 (16) | 7 (11) | 7 (15) | – | |

| Total pancreatectomy | 7 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 2 (12) | |

| Venous resection, n (%) | 49 (29) | 13 (30) | 14 (23) | 15 (33) | 7 (44) | 0.36 |

| Arterial resection, n (%) | 8 (5) | 4 (9) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (6) | 0.35 |

| Clavien Grade 3+ complication, n (%) | 32 (20) | 9 (21) | 12 (20) | 7 (16) | 4 (27) | 0.84 |

| LOS (days), median (IQR) | 9 (4) | 9.5 (5) | 9 (5) | 8 (3) | 10.5 (6) | 0.29 |

| 30 day readmission, n (%) | 24 (14) | 4 (16) | 12 (20) | 5 (11) | 3 (19) | 0.38 |

| 30 day mortality | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | – | – | 0.73 |

| Adjuvant therapy, n (%) | 86 (51) | 22 (50) | 32 (52) | 25 (54) | 7 (44) | 0.90 |

LOS, length of stay; IQR, interquartile range.

Survival

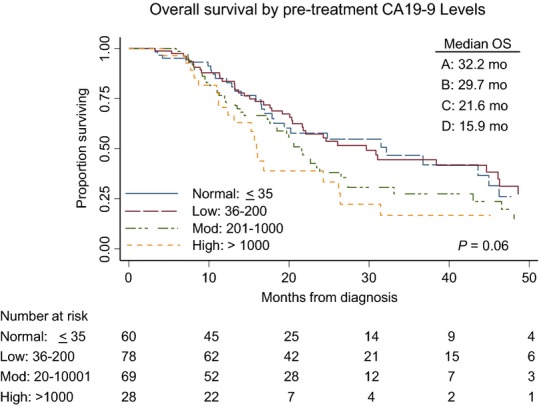

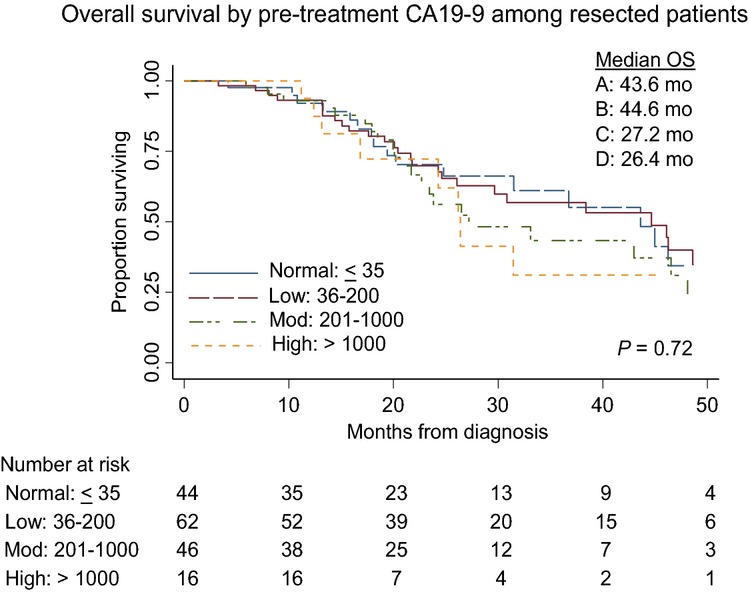

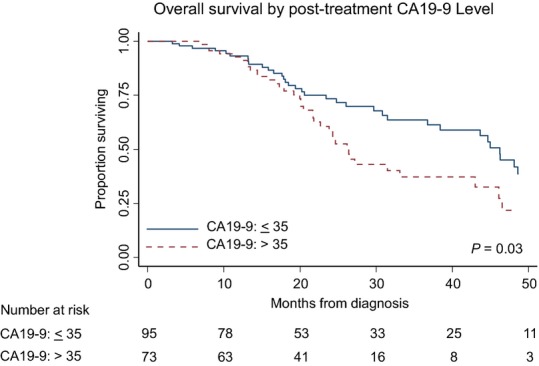

The median overall survival of all 235 patients was 23.8 months; 32.2 months, 29.7 months, 21.6 months and 15.9 months for normal, low, moderate and high CA19-9 groups, respectively (log rank P = 0.06) (Fig.2). This suggests that there is an inverse relationship between the pre-treatment CA19-9 value and overall survival in an intention-to-treat analysis. In an univariable Cox proportional hazards model, which included all patients, several factors including CCI > 5 (HR 1.86; 95%CI: 1.19–2.9), elevated post-treatment CA19-9 (HR 1.98; 1.38–2.86) and BLR stage (HR 1.89; 1.31–2.72) were identified as being negatively associated with survival. Completion of all intended therapy to include successful surgery was strongly associated with improved survival (HR 0.15: 95%CI: 0.10–0.22) and was the most powerful prognostic factor by multivariable analysis (HR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.12–0.29) (Table3). Among the 168 patients who completed all intended therapy including surgery, the median overall survival was 38.4 months; 43.6 months, 44.7 months, 27.2 months and 26.4 months for normal, low, moderate and high CA19-9 groups, respectively (log rank P = 0.72) (Fig.3). When these patients were stratified by post-treatment CA19-9 levels, the median overall survivals for normal versus elevated post-treatment CA19-9 groups were 46.2 and 26.4 months (P = 0.03) (Fig.4). Among resected patients, the only prognostic variable identified in both univariable and multivariable analysis was the presence of an elevated post-treatment CA19-9, which was associated with a 1.74-fold increased risk of death (95% CI: 1.08–2.81) (Table4).

Figure 2.

Overall survival (OS) of 235 patients with localized pancreatic cancer by pre-treatment with the carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 subgroup

Table 3.

Cox's proportional hazards regression analysis – all patients (n = 235)

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (ref: < 65 years) | 0.89 | 0.63–1.26 | 0.51 | |||

| Male Gender (ref: female) | 1.36 | 0.96–1.92 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 0.78–1.62 | 0.52 |

| CCI >5 (ref: < 5) | 1.86 | 1.19–2.91 | 0.006 | 1.30 | 0.79–2.13 | 0.29 |

| CA19-9 category | ||||||

| Normal: ≤35 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Low: 36–200 | 0.90 | 0.56–1.45 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.51–1.44 | 0.57 |

| Moderate: 201–1000 | 1.33 | 0.83–2.14 | 0.24 | 0.89 | 0.49–1.60 | 0.71 |

| High: >1000 | 1.76 | 0.98–3.16 | 0.06 | 1.18 | 0.58–2.36 | 0.64 |

| Elevated Preop CA19-9 > 35 (ref: < 35) | 1.98 | 1.38–2.86 | <0.001 | 1.48 | 0.93–2.36 | 0.10 |

| Borderline Resectable (ref: resectable) | 1.89 | 1.31–2.72 | 0.001 | 1.31 | 0.83–2.06 | 0.23 |

| Completed Neoadjuvant Tx and Surgery (ref: no) | 0.15 | 0.10–0.22 | <0.001 | 0.20 | 0.12–0.29 | <0.001 |

| Rec'd Adjuvant therapy (ref: no) | 0.42 | 0.28–0.64 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 0.52–1.53 | 0.69 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CCI, Charlson's comorbidity index; CA, carbohydrate antigen.

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) of 168 patients with resected pancreatic cancer after neoadjuvant therapy by pre-treatment with the carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 subgroup

Figure 4.

Overall survival of 168 patients with resected pancreatic cancer after neoadjuvant therapy by post-treatment with carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 status

Table 4.

Cox's proportional hazards regression analysis-resected patients (n = 168)

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (ref: < 65 years) | 0.90 | 0.57–1.43 | 0.51 | |||

| Male Gender (ref: female) | 1.13 | 0.71–1.79 | 0.60 | |||

| CCI >5 (ref: < 5) | 1.13 | 0.51–2.46 | 0.76 | |||

| CA19-9 category | ||||||

| Normal: ≤35 | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Low: 36–200 | 0.88 | 0.49–1.62 | 0.70 | |||

| Moderate: 201–1000 | 1.33 | 0.61–2.14 | 0.69 | |||

| High: >1000 | 1.34 | 0.58–3.08 | 0.50 | |||

| Elevated Preop CA19-9 > 35 (ref: < 35) | 1.67 | 1.05–2.67 | 0.03 | 1.74 | 1.08–2.81 | 0.02 |

| Borderline Resectable (ref: resectable) | 1.42 | 0.89–2.26 | 0.14 | 1.55 | 0.97–2.48 | 0.07 |

| Node positive (ref: node negative) | 1.43 | 0.88–2.34 | 0.14 | 1.37 | 0.84–2.24 | 0.21 |

| Rec'd Adjuvant therapy (ref: no) | 0.82 | 0.51–1.31 | 0.40 | |||

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CCI, Charlson's comorbidity index; CA, carbohydrate antigen.

Discussion

A universal tenet of solid tumour oncology is the utilization of stage-specific therapy to facilitate the selection of the best treatment (based on extent of disease) for each individual patient in an effort to maximize survival and quality of life for all treated patients. The success of achieving this goal is predicated on the ability to discriminate accurately between different disease stages. Although the staging of PC was once defined by operative exploration of the abdomen, the current staging of PC is now based on a precise, objective, radiological classification of critical tumour-vessel relationships and the presence/absence of extrapancreatic disease.15 The mainstay of current staging involves contrast enhanced CT, which provides highly accurate assessments of such tumour–vessel relationships.20 However, CT is imperfect at identifying extra-pancreatic metastases, with 10–20% of PC patients discovered to have unanticipated metastases at the time of laparoscopy or laparotomy.21 Furthermore, in a study of 285 PC patients who underwent a surgery-first approach, 76% had metastatic disease at the time of first recurrence.5 Rapid autopsies performed on patients with resected PC also demonstrated that 85% of patients die of metastatic disease.4 Therefore, the majority of patients with presumed localized PC have clinically occult metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. Furthermore, the current method of radiographical staging, while highly specific for the assessment of primary tumour anatomy, cannot discriminate between patients who have microscopic, radiographically occult metastatic disease (majority) and patients who may truly have localized disease (minority). As a result, many PC patients who undergo an immediate surgical resection have metastatic disease at the time of operation and it is not surprising that the 5-year survival rates for such patients range from 15% to 20%.1

The application of locoregional therapies to a population of patients with a high likelihood of having systemic disease should be performed with caution. A rational alternative to a surgery-first approach for patients with PC is the utilization of neoadjuvant therapy, which allows for the early delivery of systemic therapy for the treatment of occult micrometastatic disease. Information regarding the disease status (extent of disease) and its tumour biology (treatment resistant versus sensitive) can be determined during the neoadjuvant treatment period and at the time of post-treatment restaging. The limitations of pre-treatment radiographical staging in the accurate identification of metastatic disease can be overcome, in part, with the assessment of a response to neoadjuvant therapy, as occult metastatic disease is unmasked at the time of post-treatment restaging in 26–34% of patients.22,23 Currently, all consensus guidelines recommend neoadjuvant therapy for patients with BLR PC.24,25 However, as the majority of patients with PC have metastatic disease at diagnosis (regardless of stage of disease), several institutions (including the authors) utilize neoadjuvant therapy for the management of all patients with localized PC, including those with resectable disease. In contrast to a surgery-first approach, the median overall survival of patients with localized PC who completed all intended neoadjuvant therapy to include successful surgery ranges from 31 to 34 months.22,23 Despite the nearly 12-month prolongation in overall survival among patients who are able to complete all intended neoadjuvant therapy and surgery (compared with those treated with surgery first), it is important to note that disease recurrence remains common. Additional prognostic markers are needed to discriminate further which patients are likely to develop early disease recurrence after completion of all intended therapy and those likely to have a prolonged survival benefit.

CA19-9 is a sialyated Lewis antigen that has been extensively studied in patients with PC. Several reports have demonstrated that pre-operative CA19-9 is associated with tumour stage, resectability, the risk of recurrence and survival in patients with localized PC treated with a surgery-first approach.7,9,12,26,27 One of the first studies to describe the prognostic importance of CA19-9 examined 176 patients with localized PC.7 CA19-9 was found to correlate with the AJCC pathological stage, as well as post-resection survival. Of note, patients with pre-operative CA19-9 values greater than 1000 U/ml had a median overall survival of only 12 months as compared to 28 months for patients with CA19-9 values < 1000 U/ml. Similarly, in the largest study examining pre-treatment CA19-9, which involved 1626 patients with localized PC, Hartwig et al. observed a strong inverse relationship between pre-operative CA19-9 levels and both R0 resection rates and overall survival.12 In their study, 312 patients had a pre-treatment CA19-9 level >1000 U/ml and in this subgroup, there were no 5-year survivors; the median overall survival after resection was approximately 12 months. As a result, the authors concluded that patients with CA19-9 levels >1000 are at a high risk for the development of metastatic disease and a neoadjuvant treatment approach should be considered.

In the present study, we also observed that pre-treatment CA19-9 was inversely associated with survival (Fig.2). We observed that higher pre-treatment CA19-9 was associated with failure to complete all intended therapy, specifically due to the development of metastatic disease that precluded surgical resection. Interestingly, among patients who were able to complete all intended neoadjuvant therapy and successful surgery, the prognostic value of the pre-treatment CA19-9 was attenuated (Fig.3). Although there were clinically significant differences in overall survival between the pre-treatment CA19-9 subgroups, this did not reach statistical significance. Furthermore, in a multivariate Cox's proportional hazards model, the pre-treatment CA19-9 subgroup was not a prognostic marker for survival duration. Of the 175 patients with elevated pre-treatment CA19-9, 173 had evaluable post-treatment CA19-9 that became normal in 59 (34%) patients, suggesting a robust therapeutic response to neoadjuvant therapy. Of the 28 patients with pre-treatment CA19-9 greater than 1000 U/ml, 16 (57%) completed all intended neoadjuvant therapy and surgery, and these 16 patients had a median overall survival of 26.4 months. Although high pre-treatment CA19-9 levels have been associated with a poor overall survival, in our experience, over 50% of such patients were able to complete all intended neoadjuvant therapy including surgery and they had a median overall survival of >2 years. Therefore, elevated pre-treatment CA19-9 should not be a contraindication to embarking on a potentially curative programme of neoadjuvant treatment sequencing.

Changes in CA19-9 levels may be associated with a tumour response, and the normalization of CA19-9 after a surgical resection has been associated with an improved prognosis in several surgical series.7,12,26 Among patients with advanced PC, the early decrease in CA19-9 levels was associated with objective changes in radiographical response and survival.11,28,29 Similarly, among patients with localized PC, a decrease in CA19-9 in response to neoadjuvant therapy has previously been reported to correlate with overall survival.13,14 In a study of 78 patients with localized PC, a 50% reduction in pre-treatment CA19-9 after neoadjuvant therapy was associated with an improved overall survival (28 versus 11 months, P < 0.0001).13 In another study of 82 patients with lo calized PC, a decline in CA19-9 after neoadjuvant therapy was also associated with an improved survival (25.7 months versus 10.4 months, P = 0.01).14 In the present study of 235 patients, we observed that the normalization of CA19-9, after neoadjuvant therapy, was associated with the successful completion of all intended therapy in a univariable logistic regression model (HR: 1.98; P < 0.001), but lost statistical significance in a multivariable model (HR: 1.47; P = 0.10). Not surprisingly, the strongest prognostic factor for survival was the completion of all intended neoadjuvant therapy and surgery. However, of the 168 patients in whom successful resection was achieved, the single most powerful prognostic factor for survival was the normalization of post-treatment/pre-operative CA19-9. Patients with elevated post-treatment/pre-operative CA19-9 had a 1.8-fold increased risk of death as compared with patients with normal post-treatment CA19-9 (P = 0.02). As such, our present study confirms earlier reports that post-treatment/pre-operative CA19-9 is an important prognostic indicator for overall survival among patients who undergo a pancreatectomy.

The prognostic value of post-treatment/pre-operative CA19-9 adds additional support to the hypothesis that the delivery of systemic therapy prior to surgery may be more effective than the delivery of systemic therapy in the post-operative setting. In the study by Hartwig et al., patients with pre-operative CA19-9 levels > 1000, who underwent a pancreatectomy, had a survival duration of approximately 12 months. Presumably all patients were offered adjuvant therapy owing to their high pre-operative CA19-9 levels, although the proportion of patients who received adjuvant therapy was not provided. We know that adjuvant therapy cannot be successfully delivered to all patients after a major pancreatic operation. This is one of the significant limitations of a surgery-first treatment approach.30 Importantly, in the present report, 16 (57%) of the 28 patients with a pre-treatment CA19-9 > 1000, who successfully completed all intended therapy, had a median survival of 24 months – double that in the report by Hartwig and colleagues. Among this high-risk subgroup, as expected, only 44% received adjuvant therapy. Why is the survival of these two cohorts of high-risk patients so disparate? Could the survival advantage be because of treatment sequencing? The improvement in overall survival in the neoadjuvant treatment group (24 months versus 12 months for surgery-first) may be owing to the delivery of early systemic therapy in an immune-competent patient. Although several millennia of experience support the use of surgical resection to impart a cure in patients with localized PC, the vast majority of patients who are treated with a surgery-first strategy harbour distant metastases, even if radiographically occult. It is now accepted that major surgery suppresses the immune system for several days and that more invasive procedures are associated with longer and more profound immunosuppression.31 Suppression of cell-mediated immunity occurs through multiple mechanisms including the release of tumour cells, the reduction of antiangiogenic factors, and the induction of growth factors, which all can be further modified by tissue damage, the use of blood products, hypothermia and pain management.32 Immunosuppression has long been recognized to be associated with an increase in metastatic disease progression as observed in transplant patients and those with AIDS.33,34 Whether or not the immunosuppression associated with a pancreatic resection is significant enough to enhance disease progression at distant sites is unknown, but this may have important implications with regards to treatment sequencing. For the majority of patients who have subclinical metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, the effect of surgically induced immunosuppression (surgery first approach) may be very important – especially for those whose disease would have been sensitive to the selected systemic therapy.

There are some well-described limitations of the use of CA19-9 as a prognostic biomarker. First, approximately 10% of Caucasians and 22% of African Americans lack either the Lewis gene or the secretory gene, and, therefore, will not have an elevated CA19-9 even in the presence of PC.35,36 In addition, CA19-9 can be elevated in benign pancreatic disease and the setting of cholestasis.37,38 Nevertheless, a wealth of data exists to support the prognostic value of CA19-9 levels in patients with PC and the routine incorporation of CA19-9 at the time of restaging assessments may provide important insight into treatment response. Given the limitations of radiographic staging that underestimates disease extent in most patients with PC, more sensitive techniques are needed which prospectively incorporate validated biomarkers. Blood-based biomarkers, whether biochemical, such as CA19-9, or cellular, such as circulating tumour cells, may be critical to the design of future clinical trials which stratify patients by prognostic biomarkers rather than relying solely on radiographical or pathological staging (Fig.5).

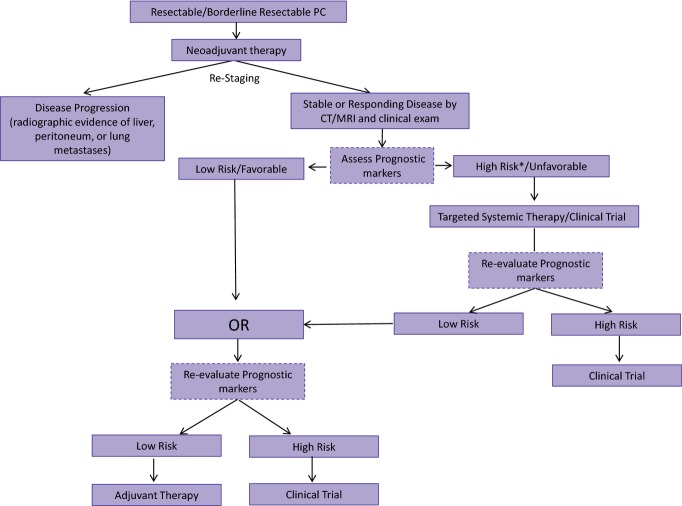

Figure 5.

The future of neoadjuvant therapy for localized pancreatic cancer will emphasize systemic therapy followed by biomarker assessment of a tumour response. Patients with a favourable biomarker profile will then receive local therapy (surgery with or without pre-operative chemoradiation) and those with an unfavourable (High Risk*) biomarker profile (suggesting that local therapy would be unlikely to provide a durable disease-free interval) would receive a different combination of systemic therapy (perhaps targeted to the unique molecular signature of their tumour based on genetic analysis of biopsy material). Local therapy (especially surgery) will be reserved for those with a favourable biomarker response; those patients whose's survival duration (based on biomarker response) is predicted to be long enough to make the morbidity of surgery worth the anticipated benefit

Conclusions

Pre-treatment serum CA19-9 levels are clinically useful in assessing the risk for decreased survival in patients with PC who are treated with neoadjuvant therapy. However, even patients with very high pre-treatment CA19-9 levels may derive a meaningful survival benefit with a neoadjuvant approach. Such patients can be identified by their decline in post-treatment CA19-9 level in response to neoadjuvant therapy. Importantly, the CA19-9 response to induction therapy provides a window through which we can begin to understand a complex tumour biology which defines PC – additional biomarkers under development will add to the value of post-treatment/pre-operative CA19-9 and provide physicians a much more accurate prediction of whether surgery will provide a clinically meaningful benefit to an individual patient.

Funding sources

American Cancer Association Pilot Grant, We Care Fund for Medical Innovation and Research, Ronald Burklund Eich Pancreatic Cancer Research Fund, Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1199–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.018. ; discussion 210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter JM, Brennan MF, Tang LH, D'Angelica MI, Dematteo RP, Fong Y, et al. Survival after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: results from a single institution over three decades. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:169–175. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1900-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal DP, Walsh RM, Ramanathan RK, Khorana AA. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: treating a systemic disease with systemic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju011. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, Luo M, Abe H, Henderson CM, et al. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1806–1813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnerlich JL, Luka SR, Deshpande AD, Dubray BJ, Weir JS, Carpenter DH, et al. Microscopic margins and patterns of treatment failure in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 2012;147:753–760. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Talamonti MS. National failure to operate on early stage pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246:173–180. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180691579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrone CR, Finkelstein DM, Thayer SP, Muzikansky A, Fernandez-delCastillo C, Warshaw AL. Perioperative CA19-9 levels can predict stage and survival in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2897–2902. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barugola G, Partelli S, Marcucci S, Sartori N, Capelli P, Bassi C, et al. Resectable pancreatic cancer: who really benefits from resection? Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3316–3322. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0670-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton JG, Bois JP, Sarr MG, Wood CM, Qin R, Thomsen KM, et al. Predictive and prognostic value of CA 19-9 in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2050–2058. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisey NR, Norman AR, Hill A, Massey A, Oates J, Cunningham D. CA19-9 as a prognostic factor in inoperable pancreatic cancer: the implication for clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:740–743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess V, Glimelius B, Grawe P, Dietrich D, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, et al. CA 19-9 tumour-marker response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer enrolled in a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:132–138. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig W, Strobel O, Hinz U, Fritz S, Hackert T, Roth C, et al. CA19-9 in potentially resectable pancreatic cancer: perspective to adjust surgical and perioperative therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2188–2196. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone BA, Steve J, Zenati MS, Hogg ME, Singhi AD, Bartlett DL, et al. Serum CA 19-9 response to neoadjuvant therapy is associated with outcome in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:4351–4358. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3842-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz MH, Varadhachary GR, Fleming JB, Wolff RA, Lee JE, Pisters PW, et al. Serum CA 19-9 as a marker of resectability and survival in patients with potentially resectable pancreatic cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1794–1801. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0943-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel BL, Tolat P, Evans DB, Tsai S. Current staging systems for pancreatic cancer. Cancer J. 2012;18:539–549. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318278c5b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christians KK, Tsai S, Tolat PP, Evans DB. Critical steps for pancreaticoduodenectomy in the setting of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:33–38. doi: 10.1002/jso.23166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th edn. New York: Springer; 2010. Exocrine and Endocrine Panceas; pp. 241–250. , eds. (. In:. ISBN: 978-0-387-88440-0. [Google Scholar]

- Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Cao HS, Balachandran A, Wang H, Nogueras-Gonzalez GM, Bailey CE, Lee JE, et al. Radiographic tumor-vein interface as a predictor of intraoperative, pathologic, and oncologic outcomes in resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:269–278. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2374-3. ; discussion 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman SP, Kawamoto S, Law JK, Blackford A, Lennon AM, Wolfgang CL, et al. Institutional experience with solid pseudopapillary neoplasms: focus on computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, conventional ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound, and predictors of aggressive histology. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2013;37:824–833. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31829d44fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DB, Varadhachary GR, Crane CH, Sun CC, Lee JE, Pisters PW, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3496–3502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadhachary GR, Wolff RA, Crane CH, Sun CC, Lee JE, Pisters PW, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine and cisplatin followed by gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3487–3495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempero MA, Arnoletti JP, Behrman S, Ben-Josef E, Benson AB, 3rd, Berlin JD, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:972–1017. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DB, Farnell MB, Lillemoe KD, Vollmer C, Jr, Strasberg SM, Schulick RD. Surgical treatment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreas cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1736–1744. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphris JL, Chang DK, Johns AL, Scarlett CJ, Pajic M, Jones MD, et al. The prognostic and predictive value of serum CA19.9 in pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1713–1722. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrini O, Schmidt CM, Moreno J, Parikh P, Matos JM, House MG, et al. Very high serum CA 19-9 levels: a contraindication to pancreaticoduodenectomy? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1791–1797. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0916-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reni M, Cereda S, Balzano G, Passoni P, Rognone A, Fugazza C, et al. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 change during chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:2630–2639. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong D, Ko AH, Hwang J, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Tempero MA. Serum CA19-9 decline compared to radiographic response as a surrogate for clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer receiving chemotherapy. Pancreas. 2008;37:269–274. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31816d8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo SC, Gilson MM, Herman JM, Cameron JL, Nathan H, Edil BH, et al. Management of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: national trends in patient selection, operative management, and use of adjuvant therapy. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sietses C, Beelen RH, Meijer S, Cuesta MA. Immunological consequences of laparoscopic surgery, speculations on the cause and clinical implications. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999;384:250–258. doi: 10.1007/s004230050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhar G, Ben-Eliyahu S. Potential prophylactic measures against postoperative immunosuppression: could they reduce recurrence rates in oncological patients? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:972–992. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detry O, Honore P, Meurisse M, Jacquet N. Cancer in transplant recipients. Transpl Proc. 2000;32:127. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00908-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn I. The effect of immunosuppression on pre-existing cancers. Transplantation. 1993;55:742–747. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199304000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard EM, Hein HO, Meyer H, Grunnet N, Jorgensen J, Wolf H, et al. Reference values and biological variation for tumor marker CA 19-9 in serum for different Lewis and secretor genotypes and evaluation of secretor and Lewis genotyping in a Caucasian population. Clin Chem. 1999;45:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempero MA, Uchida E, Takasaki H, Burnett DA, Steplewski Z, Pour PM. Relationship of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and Lewis antigens in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1987;47:5501–5503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann DV, Edwards R, Ho S, Lau WY, Glazer G. Elevated tumour marker CA19-9: clinical interpretation and influence of obstructive jaundice. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:474–479. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SL, Sachdeva A, Garcea G, Gravante G, Metcalfe MS, Lloyd DM, et al. Elevation of carbohydrate antigen 19.9 in benign hepatobiliary conditions and its correlation with serum bilirubin concentration. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3213–3217. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0289-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]