Abstract

Clinical trials often represent an increasingly important option for patients with cancer, thus oncologists participating in clinical research need to consider and address the financial burden associated with trial participation. Future research efforts should focus on developing formal screening tools to identify and monitor for financial burden among clinical trial participants.

Keywords: Cost of illness, Health care costs, Clinical trial, Financial support, Quality of life

Cancer clinical trial participants frequently struggle with financial burdens related to their care. Two patients, both eager to join a clinical trial but unable to meet the personal expenses involved, illustrate a common dilemma.

Mr. A has leukemia and elected to participate in an early phase clinical trial involving an inhibitor of the isocitrate dehydrogenase mutant protein. He had a steady job and adequate medical insurance but now is unable to work. His lack of savings left him ill-prepared to cope with the additional costs associated with clinical trial participation, including trips for monitoring his blood counts, imaging, and bone marrow biopsies. Although his insurance covers the expenses related to routine care and the trial sponsor pays for additional testing, Mr. A still bears the costs of his deductibles and the added travel, meals, and incidental expenses. His clinical trial requires weekly clinic visits with blood draws for at least 3 months along with monthly bone marrow biopsies and four echocardiograms.

Mrs. B has metastatic breast cancer and chose to participate in an early phase clinical trial involving a novel therapy targeting a somatic mutation in her tumor. She previously worked full time and earned a lucrative salary but now is unable to work. Mrs. B travels from out of state for her clinical trial visits and has spent more than $5,000 in the past 3 months on out-of-pocket medical and travel expenses. Her trial requires weekly clinic visits for the first 2 months and biweekly visits for the following 4 months. In addition, the study requires radiologic imaging studies every 8 weeks. The added costs associated with clinical trial participation will deplete her family’s savings and may force them to sell their house.

Both Mr. A and Mrs. B fear that they may have to forgo ongoing participation in their clinical trials due to the personal costs entailed.

Clinical trials are vital to the development of novel therapies for patients with cancer, yet estimates suggest that less than 7% of eligible patients participate [1–4]. Although a number of factors contribute to this low participation rate [5, 6], including access to trials and eligibility requirements, we need to better understand and remove the financial barriers to patient participation. Most discussions about the costs of clinical trials have focused on the costs to the study sponsor and to payers [7, 8]. Although these issues are important, little attention has been paid to the direct costs to the patient. Patients with cancer enrolled in clinical trials experience the same financial pressures that all cancer patients bear, yet they also must endure the added costs of more frequent clinical visits, added tests, and distant travel, all while absorbing the loss of income due to missed work [9, 10]. Although the Affordable Care Act requires coverage of routine care costs for individuals participating in approved clinical trials [11], many trial participants still have high additional out-of-pocket expenses. They must still endure the costs associated with insurance deductibles and the additional travel, meals, lodging, and other incidental expenses associated with participating in trials. In the modern era of targeted therapy, many of the most promising clinical trials are in the early phases and geared toward patients with cancers that express a specific biomarker. Typically, these trials are available only at certain academic cancer centers, which may require participants to travel considerable distances to and from these cancer centers.

The Institute of Medicine has highlighted the need for increased participation in cancer clinical trials and identified obstacles to enrollment [3]. These include lack of patient and/or provider knowledge about clinical trials, complexity of the eligibility requirements, expenses involved in participation, and difficulty with travel to trial sites [3, 12]. Research has shown that patients with higher socioeconomic status (SES) enroll more frequently in cancer clinical trials than those with lower SES [13, 14]. These patients have financial resources that enable them to bear the personal cost of enrollment in trials. In addition, more highly educated patients may better understand the potential benefits of the trial and the impact of research advances. Alternatively, elderly, uninsured, and minority patients, all of whom may have more limited financial resources and access to information, are underrepresented in cancer clinical trials [1, 15–17]. This disparity has ethical implications and also threatens the generalizability of trial results by excluding certain racial, ethnic, and demographic subgroups.

Despite the paucity of data focusing on the additional financial burden related to participation in cancer clinical trials, evidence continues to mount about the financial burden experienced by the general cancer population [18–21]. In response to this burden, patients may reduce spending on food and clothing, sell possessions or property, and even decide not to adhere to aspects of the treatment plan [19]. The added costs of clinical trial enrollment can only exacerbate the financial burden experienced by cancer patients, yet the existing literature rarely addresses the financial aspects of clinical trial participation.

Classically, when developing clinical trials, cost discussions involve only the cost to the trial sponsor [22]. Researchers rarely assess the financial burden of patients in their studies, despite the increased use of other patient-reported outcomes, such as symptom assessments and quality of life (QOL) [23–25]. One specific QOL questionnaire, the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), assesses QOL and symptoms, yet it also contains a question about patients’ financial difficulties [25, 26]. Using the EORTC QLQ-C30, one recent trial compared chemotherapy weekly versus every 3 weeks for breast cancer patients and found that the patients treated weekly experienced greater financial burden [27]. Thus, tools exist to help monitor the financial impacts of clinical trial participation, but data on their use are limited.

Although the existing literature lacks much information regarding the financial burden experienced by cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials, efforts to prevent and alleviate this burden focus primarily on providing accommodations to pediatric patients and their families. Charitable programs such as the Ronald MacDonald House, the American Cancer Society Hope Lodge, and institutional support from St. Jude help support children’s cancer treatment and clinical research. To our knowledge, the program at the National Institutes of Health represents the only consistent program for adults that supports travel, meals, and lodging for cancer clinical trial participants [28].

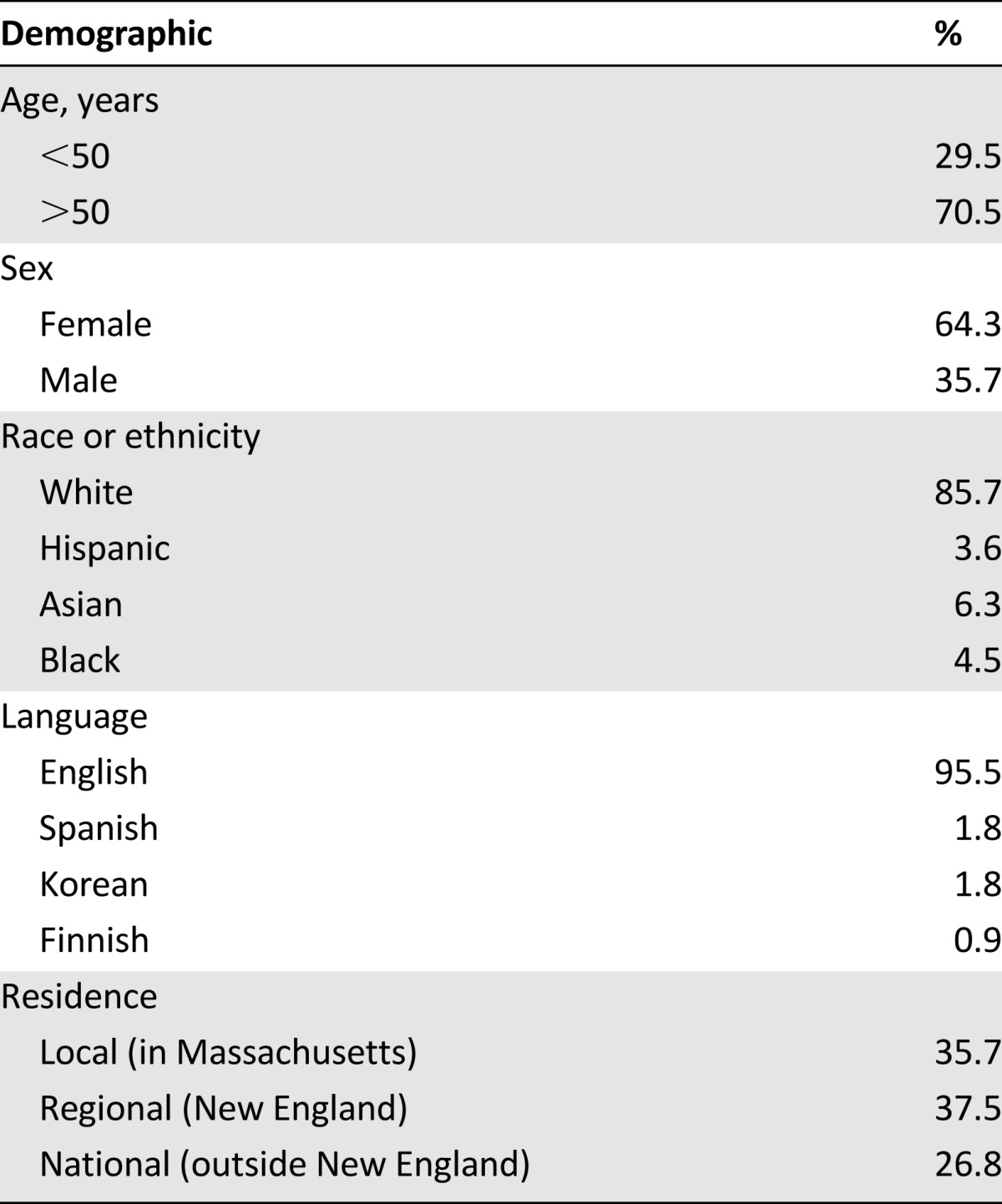

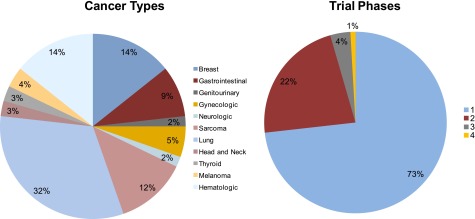

At the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cancer Center, we have partnered with the Lazarex Cancer Foundation to form a Cancer Care Equity Program (CCEP) to begin to address the financial burden of clinical trial participation. Through the CCEP, we aim to better understand the financial impact of clinical trial participation and to provide financial assistance for trial-related expenses, such as travel and lodging. In the initial phase of the program, we offered support for clinical trial participants who expressed a financial need and/or who reported financial impediments to ongoing trial participation. To date, we have not developed a standard tool for assessment of patients’ financial need to determine priorities for allocation of financial support. Between November 2013 and May 2014, a total of 112 clinical trial participants enrolled in the CCEP. These 112 enrollees represented more than 10% of clinical trial participants at MGH for this period. Of these enrollees, 71% were aged older than 50 years, 64% were women, 14% were racial or ethnic minorities, 5% did not speak English, 9% reported annual income under $35,000 per year, and 64% resided out of state (Table 1). Most cancer types were represented, the largest fraction being lung cancer (32%) (Fig. 1). Most participants (73%) were enrolled in a phase I clinical trial.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

Figure 1.

Cancer types and trial phases of patients enrolled in the Cancer Care Equity Program.

On average, patients enrolled in the CCEP spent more than $600 per month to pay for the additional costs of travel and lodging when enrolled in clinical trials at MGH. On average, Massachusetts patients spent more than $200 per month, regional patients (New England, excluding Massachusetts) spent more than $300, and out-of-region patients spent more than $900. These costs represent only a fraction of the estimated research costs borne by sponsors of clinical trials [22, 29] but present a significant hurdle to the cancer patient already beset by financial concerns. We have begun the next phase of our program, which includes the development of a formal assessment of patients’ financial needs. This financial needs assessment will include patients’ income levels, out-of-pocket costs, and self-reported measures about their financial burden. The CCEP will continue to help alleviate the financial burden associated with clinical trial participation for people like Mr. A and Mrs. B, both of whom maintained their trial participation with the help of the CCEP.

Clinical trial participants represent a population uniquely vulnerable to financial burden related to their cancer care. Future research efforts should focus on developing formal screening tools to identify and monitor for financial burden among clinical trial participants. Such a screening tool should use evidence from the available literature and consider patients’ income, financial resources and constraints, out-of-pocket costs, and self-reporting of the impact of financial distress [19, 30]. An effective screening tool to determine patients in greatest need of assistance would help prioritize limited resources and provide better understanding of the impacts of financial assistance programs. Clinical trials often represent an increasingly important option for patients with cancer, thus oncologists participating in clinical research need to consider and address the financial burden associated with trial participation.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: See the related commentary, “Clinical Trials, Disparities, and Financial Burden: It’s Time to Intervene,” on page 571 of this issue.

For Further Reading: S. Yousuf Zafar, Jeffrey M. Peppercorn, Deborah Schrag et al. The Financial Toxicity of Cancer Treatment: A Pilot Study Assessing Out-of-Pocket Expenses and the Insured Cancer Patient's Experience. The Oncologist 2013;18:381–390.

Implications for Practice: The number of insured patients is increasing, but insured patients are paying more out of pocket for cancer care due to increased cost sharing. As a result, the number of underinsured cancer patients is increasing. Patients are faced with greater out-of-pocket health care costs, but treatment decision making is often made without consideration of these expenses. In our study, insured patients undergoing cancer treatment and seeking copayment assistance experienced considerable subjective financial burden, and they altered care to defray out-of-pocket expenses. Health insurance does not eliminate financial distress or health disparities among cancer patients. Financial distress or “financial toxicity” as a result of disease or treatment decisions might be considered analogous to physical toxicity and might be considered a relevant variable in guiding cancer management. Understanding how and among whom to best measure financial distress is critical to the design of future interventional studies.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Ryan D. Nipp, Elizabeth Powell, Bruce Chabner, Beverly Moy

Provision of study material or patients: Ryan D. Nipp, Elizabeth Powell, Bruce Chabner, Beverly Moy

Collection and/or assembly of data: Ryan D. Nipp, Elizabeth Powell, Bruce Chabner, Beverly Moy

Data analysis and interpretation: Ryan D. Nipp, Elizabeth Powell, Bruce Chabner, Beverly Moy

Manuscript writing: Ryan D. Nipp, Elizabeth Powell, Bruce Chabner, Beverly Moy

Final approval of manuscript: Ryan D. Nipp, Elizabeth Powell, Bruce Chabner, Beverly Moy

Disclosures

Bruce Chabner: Sanofi, Merrimack, Zeltia (C/A, H), Seattle Genetics, Zeltia, Epizyme, PharmaCyclics Exelixis, Gilead, Celgene (OI), Eli Lilly (ET). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scoggins JF, Ramsey SD. A national cancer clinical trials system for the 21st century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1371. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nass SJ, Moses HL, Mendelsohn J, editors. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouad MN, Lee JY, Catalano PJ, et al. Enrollment of patients with lung and colorectal cancers onto clinical trials. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:e40–e47. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somkin CP, Altschuler A, Ackerson L, et al. Organizational barriers to physician participation in cancer clinical trials. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu S, McQuinn L, Naing A, et al. Barriers to study enrollment in patients with advanced cancer referred to a phase I clinical trials unit. The Oncologist. 2013;18:1315–1320. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldman DP, Schoenbaum ML, Potosky AL, et al. Measuring the incremental cost of clinical cancer research. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:105–110. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin PJ, Davenport-Ennis N, Petrelli NJ, et al. Responsibility for costs associated with clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3357–3359. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lara PN, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman DP, Berry SH, McCabe MS, et al. Incremental treatment costs in National Cancer Institute-sponsored clinical trials. JAMA. 2003;289:2970–2977. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: Opportunities in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3816–3824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young RC. Cancer clinical trials—a chronic but curable crisis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:306–309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1005843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2109–2117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baquet CR, Ellison GL, Mishra SI. Analysis of Maryland cancer patient participation in National Cancer Institute-supported cancer treatment clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3380–3386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umutyan A, Chiechi C, Beckett LA, et al. Overcoming barriers to cancer clinical trial accrual: Impact of a mass media campaign. Cancer. 2008;112:212–219. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R. Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: A 7-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4626–4631. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3112–3124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients’ families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA. 1994;272:1839–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.23.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. The Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stump TK, Eghan N, Egleston BL, et al. Cost concerns of patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:251–257. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2821–2826. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emanuel EJ, Schnipper LE, Kamin DY, et al. The costs of conducting clinical research. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4145–4150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basch E, Snyder C, McNiff K, et al. Patient-reported outcome performance measures in oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:209–211. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brundage M, Blazeby J, Revicki D, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in randomized clinical trials: Development of ISOQOL reporting standards. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1161–1175. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0252-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niezgoda HE, Pater JL. A validation study of the domains of the core EORTC quality of life questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:319–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00449426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuzzo F, Morabito A, Gravina A, et al. Effects on quality of life of weekly docetaxel-based chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: Results of a single-centre randomized phase 3 trial. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Friends of the Clinical Center: Annual reports. Available at http://www.focccharities.org/Annual_Reports.html. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- 29. Clinical development and trial operations (PH192): Protocol design and cost per patient benchmarks. Available at http://www.cuttingedgeinfo.com/research/clinical-development/trial-operations/ Accessed April 27, 2015.

- 30.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120:3245–3253. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]