Abstract

The Affordable Care Act, which recently survived a second Supreme Court challenge, has increased health care access without causing most of the disruption critics feared.

Miriam Reisman

Earlier this year marked the fifth year anniversary of the signing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). It also saw the U.S. Supreme Court’s long-awaited ruling on a landmark case that had threatened to dismantle the law by revoking health insurance subsidies for millions of Americans. The lawsuit, known as King v Burwell, questioned whether individuals who purchase health insurance in the 34 states that have federally run health insurance exchanges are entitled to tax credits for their premiums and cost-sharing reductions. In what was considered a make-or-break case for the ACA, the court ultimately sided with the White House, ruling 6–3 on June 25, 2015, to uphold the health insurance subsidies regardless of whether the state or federal government administers the exchange.1

The ACA, often referred to as Obamacare, is one of the most complex and comprehensive reforms of the American health system ever enacted. It has survived an unprecedented level of scrutiny (especially by Republicans). But politics aside, is the law working as intended and meeting its primary goals?

ACA: SO FAR, SO GOOD

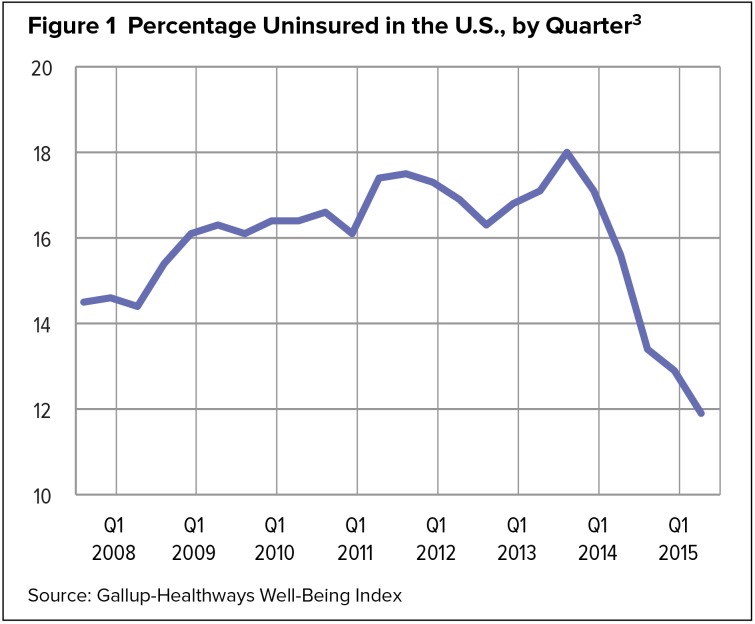

A skimming of recent headlines suggests that the ACA is not only doing what it was intended to do—increase access to quality health care—but has surpassed expectations. Studies show that the ACA is significantly reducing the number of uninsured people across the country. A recent analysis by the RAND Corporation found that nearly 17 million more Americans have become insured since the health insurance exchanges opened,2 and, according to Gallup data, the uninsured rate among U.S. adults 18 years of age and older dipped to 11.9% for the first quarter of 2015. A drop of nearly 6 percentage points since the end of 2013, this is the lowest quarterly uninsured rate since Gallup started tracking the statistic in 2008 (Figure 1).3

Figure 1.

Percentage Uninsured in the U.S., by Quarter3

Source: Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index

The RAND report found that significant gains in health coverage are spread across all types of insurance, including employer-provided coverage, government Medicaid programs, and policies offered through the state insurance marketplaces created by the law.2 The findings, published this spring in Health Affairs, are based on a survey of about 1,600 Americans ages 18 to 64 years.

A closer look reveals more about these gains, particularly across racial and ethnic, economic, and age groups. For instance, before the ACA took effect, nearly one in three young adults ages 19 to 26 years lacked health insurance coverage, primarily because of insufficient access to employer-provided insurance and subsidized public coverage.4 Since the ACA was implemented, nearly three million previously uninsured young Americans have obtained coverage under their parents’ health insurance policies.4 This is the largest increase in insurance rates of any age group,5 a direct impact of a key provision of the law that requires many health plans to extend dependent coverage up to the age of 26.

The ACA has also affected other U.S. groups that have historically been at the greatest risk for lacking insurance, including Latinos, African-Americans, and economically disadvantaged individuals. The overall uninsured rate for Latinos fell from 36% to 23% less than one year after the exchanges opened for enrollment.6 Since the enactment of the ACA, Latinos have experienced the largest gain in health coverage among all racial and ethnic groups.3 Changes in the uninsured rate between the fourth quarter of 2013 and the first quarter of 2015 (based on Gallup-Healthways surveys) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Percentage of uninsured Americans, by Subgroup3

| Q4 2013 % | Q1 2015 % | Net Change (Percentage Points) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National adults | 17.1 | 11.9 | −5.2 |

| Age | |||

| 18–25 | 23.5 | 16.8 | −6.7 |

| 26–34 | 28.2 | 20.8 | −7.4 |

| 35–64 | 18.0 | 12.0 | −6.0 |

| 65+ | 2.0 | 1.8 | −0.2 |

| Race | |||

| Whites | 11.9 | 7.7 | −4.2 |

| Blacks | 20.9 | 13.6 | −7.3 |

| Hispanics | 38.7 | 30.4 | −8.3 |

| Income | |||

| < $36,000 | 30.7 | 22.0 | −8.7 |

| $36,000–$89,999 | 11.7 | 8.2 | −3.5 |

| $90,000+ | 5.8 | 3.5 | −2.3 |

Source: Gallup–Healthways Well-Being Index

ACA PROVISIONS TIMELINE

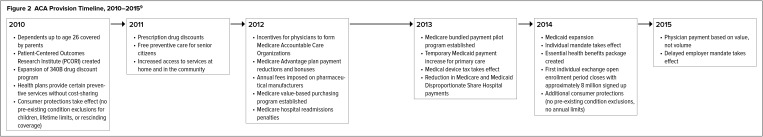

The Affordable Care Act is divided into 10 titles and contains nearly a thousand pages of provisions that touch almost every aspect of the health care system. These provisions are designed not only to expand insurance coverage but to increase consumer protections, emphasize prevention and wellness, improve quality and system performance, strengthen the health workforce, and curb rising health care costs.

Some of the ACA’s provisions became effective immediately when the law was implemented in 2010, while others are being phased in through 2020. Many of the key provisions, including the creation of exchanges with subsidies for those who qualify, expansion of Medicaid, and minimum standards for insurance plans, took effect in 2014. The New York Times reported earlier this year that these three provisions alone have already benefited at least 31 million Americans.7

Not all states have taken part in the Medicaid expansion. As of July 2015, 30 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the ACA expansion, 19 states have exercised the right to opt out, and one state, Utah, was still discussing the matter.8 There is no deadline for states to implement Medicaid expansion.

Figure 2 highlights some of the major reform provisions that have been or will be implemented through 2015.

Figure 2.

ACA Provision Timeline, 2010–20159

ACA MYTHS VERSUS FACTS

The Affordable Care Act has been shrouded in confusion and misinformation, starting well before it was signed into law. This is due partly to partisan politics and partly to poor communication about the law to the public.

One early controversy concerned whether individuals would lose their current health plans when the new law took effect. Initially, some insured people were taken by surprise when their insurers canceled policies that did not qualify as minimum essential coverage (MEC) under the ACA. Basically, MEC includes most broad-based medical coverage typically provided by employers, as well as individual market policies, Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and certain other coverage. Cancellations of plans because they do not comply with the ACA have decreased, while the insurance exchanges have offered accessible and affordable alternatives.10

In fact, studies show that the ACA has caused little change in the way most previously covered Americans are obtaining health insurance. Researchers estimate that in 2013, about 125 million Americans, or 80% of nonelderly adults, experienced no disruption to their existing coverage.2

Stirring more controversy, the business community and other critics of the ACA predicted that it would prompt employers to drop health benefits for all or some of their workers. Just 1% of employers reported that they had decided to stop offering health coverage for 2015, according to a survey of more than 3,000 employers by the Employee Benefit Research Institute and the Society for Human Resource Management.11 The survey showed little difference between larger employers and smaller ones in their coverage decisions. Under the ACA, employers with fewer than 50 workers qualify for the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP), a required program for each state’s health insurance marketplace that helps small employers provide coverage to their workers.

Also running counter to predictions that most employers would abandon health benefits, RAND researchers reported that the biggest gain in health care coverage has involved employer-sponsored insurance.2 The RAND study suggests that job-based plans will remain the country’s major source of coverage.

Other concerns involved the potential flood of new patients that would occur after the ACA’s coverage expansions took effect. How would health care providers, who are already overwhelmed, manage the increased workload? Again, these concerns have remained largely unsubstantiated, as studies show the predicted influx did not occur.12 In fact, new-patient visits to primary care providers increased only slightly, from 22.6% of total patient visits in 2013 to 22.9% in 2014.12

Further, most health care services have seen only modest increases in demand, and the current supply of hospitals, doctors, and other providers should be sufficient to meet these needs. The already growing trend toward increased roles for physician assistants and nurse practitioners is expected to help.13

Finally, newly covered patients do not appear to be sicker than those who were insured before the ACA took effect, as some commentators had worried. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation study found that the percentage of visits involving patients with complex medical needs decreased from 8% of appointments in 2013 to 7.5% in 2014 and that the number of diagnoses per patient visit did not increase sharply compared with the previous year’s data. In other words, the percentages of patients diagnosed with chronic conditions, including diabetes and hypertension, remained about the same as in past years.12

WHAT THE ACA MEANS FOR PHARMA

Five years may be too little time to tell with any certainty how health reform is affecting prescription drug coverage, cost, and use. For instance, some experts expect only modest increases in prescription drug use, while others predict a more significant rise, considering that the drug benefit is used more frequently and by more people than any other benefit.13,14 However, one thing is clear: the ACA has put in motion a number of dynamic changes that, in the long term, have the potential to significantly transform the nation’s pharmaceutical marketplace:

Prescription drug coverage is one of 10 essential health benefits required by the ACA and must now be included with all new exchange plans in the individual and small-group markets. This is a significant shift; prior to the implementation of the ACA, nearly one out of five health insurance plans purchased privately by individuals and families lacked drug benefits.15

The law requires states expanding their Medicaid programs to provide prescription drug benefits to Medicaid-eligible consumers. In 2010, 23% of adults (ages 19–64 years) covered by Medicaid and other state insurance programs reported unmet prescription drug needs because of cost concerns.16

Under the new law, plans do not have to cover all prescription drugs and may limit the drugs they include, covering only generic versions of drugs where generics are available. However, patients and their physicians can request and gain access to clinically appropriate drugs that are not covered.17

The ACA provides states and plans with considerable discretion in designing their drug benefits. Plans maintain their own formularies, and the cost for the same drug can vary significantly among plans, which can potentially affect patients with chronic conditions.

Further implications of the ACA that are expected to have a major impact on the pharmaceutical industry include:

The trend toward accountable care organizations (ACOs) and other models that increase provider accountability for the cost and quality of care. The number of ACOs more than tripled a year after ACA passage, and by the end of 2013, more than 600 ACOs were operating across the country.18

The need for cost-effective alternatives to expensive therapies.

Increased data transparency with the intent of supporting consumer decision-making and promoting high-value care.

IS THE ACA IMPROVING HEALTH AND REDUCING COSTS?

To date, most of the measurable impact of the ACA is on the availability of health insurance to the American people and on their access to care. As far as the cost and quality effects of the law, five years is a relatively short time to draw firm conclusions.

However, research is showing that the ACA has great potential to improve health and health care for people with chronic conditions such as diabetes.19 Uninsured adults 19 to 64 years of age with diabetes have less access to health care and lower levels of preventive care, health care use, and expenditures than insured adults. To the extent that the ACA increases access and coverage, uninsured people with diabetes are likely to significantly increase their health care use; this may lead to a reduced incidence of diabetes complications and improved health.19

Early findings also show unprecedented reductions in hospital-acquired conditions and Medicare readmissions since the enactment of the ACA. The legislation imposes financial penalties on hospitals that underperform in these areas, but to what extent the ACA is responsible for the improvements is still uncertain.10

THE POLITICS OF HEALTH CARE

While numerous studies show that uninsured rates have decreased sharply across the country under the ACA, and while Americans’ favorable opinion of health care reform has been rising steadily,20 the law remains as politically divisive as ever. Since 2010, the ACA has seen more than 50 repeal attempts by a Republican-led House and a previous Supreme Court challenge in 2012. That case, National Federation of Independent Business v Sebelius, led to a milestone decision by the court upholding another crucial provision of the law—the individual mandate requiring most Americans to obtain “minimum essential” health insurance starting in 2014.

The ACA is expected to be a key issue in the 2016 presidential race, with the emerging field of GOP White House hopefuls fine-tuning their campaign rhetoric. In announcing his candidacy earlier this year, Texas Senator Ted Cruz vowed to repeal “every single word” of the health care law.21 Governor Bobby Jindal of Louisiana has also promised to repeal the ACA if elected president.22

Taking a more measured approach, Senator Rand Paul (R-Kentucky) has said that while he would like to see the ACA repealed, he would consider allowing states to run their own health exchanges.23 This would include his own state’s health insurance marketplace, Kynect. However, according to Kynect’s executive director, Carrie Banahan, the exchange could not function effectively without the individual subsidies and Medicaid expansion, two key components of the health care law.24

In fact, Kentucky has been recognized as a model for other states with federally run exchanges, with more than 400,000 individuals signing up for health care coverage during the first enrollment period that ended in March 2014. Of those who registered, about 75% previously lacked health insurance.25

THE FUTURE OF OBAMACARE

“The Affordable Care Act is here to stay,” President Obama declared this spring in the wake of the Supreme Court’s second major ruling on his signature health care law. Those words rekindled the already heated discussion among health care experts, political pundits, economists, and others over the fate of the ACA. Most suggest that the only way to undo health care reform now is the election of a Republican president in 2016 and that even by then, the law may be too entrenched to uproot.

In the meantime, as remaining provisions of the ACA are phased in, governors and legislatures across the country will continue to be divided over Medicaid expansion and insurance exchanges, and legal and policy experts will continue to clash over the individual mandate, contraceptive coverage, and other components of the law. In other words, regardless of studies and statistics, it is safe to say that the Obamacare debate is still far from over.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brookings Institute Assessing the Affordable Care Act’s efficacy, implementation, and policy implications five years later. The A. Alfred Taubman Forum on Public Policy. No. 14. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/events/2015/04/14-aca-efficacy-implementation-west-kamarck. Accessed August 15, 2015.

- 2.RAND Corporation Health coverage grows under Affordable Care Act. May 6, 2015. Available at: http://www.rand.org/news/press/2015/05/06.html. Accessed June 1, 2015.

- 3.Levy J. In U.S., uninsured rate dips to 11.9% in first quarter. Gallup. Apr 13, 2015. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/182348/uninsured-rate-dips-first-quarter.aspx. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- 4.Holahan J, Kenney G. Health insurance coverage of young adults: Issues and broader consideration. Urban Institute. Jun 9, 2008. Available at: http://www.urban.org/research/publication/health-insurance-coverage-young-adults. Accessed July 14, 2015.

- 5.The Commonwealth Fund Young adults have made the greatest gains in coverage of any age group. Available at: http://new.commonwealthfund.org/interactives-and-data/chart-cart/issue-brief/rise-in-health-care-coverage-and-affordability/young-adults-have-made-the-greatest-gains-in-coverage. Accessed July 24, 2015.

- 6.Doty M, Rasmussen P, Collins S. Catching up: Latino health coverage gains and challenges under the Affordable Care Act: Results from the Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey. The Commonwealth Fund. Sep, 2014. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/∼/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2014/sep/1775_doty_catching_up_latino_hlt_coverage_aca_tb_v3.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2015. [PubMed]

- 7.Rattner S. For tens of millions, Obamacare is working. The New York Times. 2015 Feb 21; Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/02/22/sunday-review/steven-rattner-for-tens-of-millions-obamacare-is-working.html?_r=0. Accessed August 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Current status of state Medicaid expansion decisions. Jul 20, 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-of-the-medicaid-expansion-decision. Accessed July 22, 2015.

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Key features of the Affordable Care Act by year. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/timeline/timeline-text.html#2010. Accessed July 13, 2015.

- 10.Blumenthal D, Abrams M, Nuzum R. The Affordable Care Act at 5 years. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2451–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1503614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein A. Few employers dropping health benefits, surveys find. Washington Post. 2014 Nov 19; Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/few-employers-dropping-health-benefits-surveys-find/2014/11/19/1807343c-7001-11e4-893f-86bd390a3340_story.html. Accessed July 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ACAView: Tracking the impact of health care reform. Observations on the Affordable Care Act: 2014. Mar, 2015. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/03/acaview--tracking-the-impact-of-health-care-reform.html. Accessed June 1, 2015.

- 13.Glied S, Ma S. How will the Affordable Care Act affect the use of health care services? The Commonwealth Fund. Feb, 2015. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/∼/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2015/feb/1804_glied_how_will_aca_affect_use_hlt_care_svcs_ib_v2.pdf?la=en. Accessed July 14, 2015. [PubMed]

- 14.Atlantic Information Services Prescription drug benefit design in a post-ACA consumer market. Available at: http://www.aishealthdata.com/system/files/download/WhitePaperRxB_0.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- 15.Coleman K. Almost no existing health plans meet new ACA essential health benefit standards. HealthPocket.com. Mar 7, 2013. Available at: http://www.healthpocket.com/healthcare-research/infostat/few-existing-health-plans-meet-new-aca-essential-health-benefit-standards. Accessed July 21, 2015.

- 16.Boukus ER, Carrier E. Americans’ access to prescription drugs stabilizes, 2007–2010. Center for Studying Health System Change. Dec, 2011. Tracking Report No. 27. Available at: http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/1264. Accessed August 15, 2015.

- 17. HealthCare.gov Using your new marketplace health coverage: getting prescription medications. Available at: https://www.health-care.gov/using-marketplace-coverage/prescription-medications. Accessed August 15, 2015.

- 18.Petersen M, Muhlestein D. ACO results: What we know so far. Health Affairs. May 30, 2014. [blog]. Available at: http://healthaf-fairs.org/blog/2014/05/30/aco-results-what-we-know-so-far. Accessed July 22, 2015.

- 19.Brown DS, McBride TD. Impact of the Affordable Care Act on access to care for US adults with diabetes, 2011–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:140431. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Kaiser health tracking poll: March 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-march-2015. Accessed June 3, 2015.

- 21.Cruz T. Facebook post. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/SenatorTedCruz/videos/754243044687998/ < https://www.facebook.com/SenatorTedCruz/videos/754243044687998/>. Accessed July 27, 2015.

- 22.Bobby Jindal for President [website] Bobby Jindal’s plan to repeal & replace Obamacare. Available at: https://www.bobbyjindal.com/policy/health-care. Accessed August 15, 2015.

- 23.Associated Press Paul not sure what would happen to state exchange. Modern Healthcare. May 31, 2014. Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20140531/INFO/305309954. Accessed August 15, 2015.

- 24.Johnson J. What would happen to Kynect if the Affordable Care Act were repealed? WFPL News. 2014 Oct 29; Available at: http://wfpl.org/what-would-happen-to-kynect-if-the-affordable-care-act-were-repealed. Accessed July 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norris L. Kentucky health insurance exchange. HealthInsurance.org. Jul 21, 2015. Available at: http://www.healthinsurance.org/kentucky-state-health-insurance-exchange. Accessed August 15, 2015.