Abstract

AIM: The fears and concerns are associated with gastroscopy (EGD) decrease patient compliance. Conscious sedation (CS) and non-pharmacological interventions have been proposed to reduce anxiety and allow better execution of EGD. The aim of this study was to assess whether CS, supplementary information with a videotape, or presence of a relative during the examination could improve the tolerance to EGD.

METHODS: Two hundred and twenty-six outpatients (pts), scheduled for a first-time non-emergency EGD were randomly assigned to 4 groups: Co-group (62 pts): throat anaesthesia only; Mi-group (52 pts): CS with i.v. midazolam; Re-group (58 pts): presence of a relative throughout the procedure; Vi-group (54 pts): additional information with a videotape. Anxiety was measured using the "Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Scales". The patients assessed the overall discomfort during the procedure on an 100-mm visual analogue scale, and their tolerance to EGD answering a questionnaire. The endoscopist evaluated the technical difficulty of the examination and the tolerance of the patients on an 100-mm visual analogue scale and answering a questionnaire.

RESULTS: Pre-endoscopy anxiety levels were higher in the Mi-group than in the other groups (P < 0.001). On the basis of the patients' evaluation, EGD was well tolerated by 80.7% of patients in Mi-group, 43.5% in Co-group, 58.6% in Re-group, and 50% in Vi-group (P < 0.01). The discomfort caused by EGD, evaluated by either the endoscopist or the patients, was lower in Mi-group than in the other groups. The discomfort was correlated with "age" (P < 0.001) and "groups of patients" (P < 0.05) in the patients' evaluation, and with "gender" (females tolerated better than males, P < 0.001) and "groups of patients" (P < 0.05) in the endoscopist's evaluation.

CONCLUSION: Conscious sedation can improve the tolerance to EGD. Male gender and young age are predictive factors of bad tolerance to the procedure.

INTRODUCTION

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is a safe and quick procedure, and can be carried out without sedation[1]. However, it can evoke anxiety, feelings of vulnerability, embarrassment and discomfort[2], and the fears and concerns associated with endoscopic procedure decrease patient compliance[2-4]. Indeed, anxiety, discomfort, and pain are interrelated, and each may increase the others[5], making EGD execution more difficult. Several methods can be used to reduce patient pre-procedural worries, such as psychological interventions using relaxation and coping techniques[6,7], hypnosis[8], relaxation music[9], acupuncture[10], educational materials including videotapes[11], and presence of a family member during EGD[12]. However, conscious sedation with benzodiazepines is the method most widely employed[5]. Although usually safe, such medications are not free of adverse effects[13-15], and the likelihood of sedative-related complications increases in the presence of high anxiety levels, requiring higher doses of drugs[2]. It follows that the role of conscious sedation is not well defined, and its use varies from country to country: up to 98% in USA, less frequently in European countries, and quite rarely in Asia and South America[16]. The use of conscious sedation is also declining in the United Kingdom[17], and many patients who receive detailed information about the advantages and risks of sedation choose to undergo EGD with pharyngeal anesthesia alone[18,19]. In our endoscopy service, a standardized information sheet about EGD is given to all patients, and the examination is routinely performed with pharyngeal anesthesia alone.

This randomized prospective study was to evaluate if conscious sedation, additional information with a videotape, or the presence of a family member during the procedure could improve the tolerance to EGD and make the execution of EGD easier. In addition, particular emphasis was put on psychologic and procedure-related factors having a potential impact on the patient perception of tolerance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

For six consecutive months, the first two outpatients daily referred for diagnostic EGD, fulfilling the eligibility criteria, were asked to enter the study. Inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 65 years, no prior experience of endoscopic examinations, and capability (evaluated by the endoscopist) of fully understanding and filling up the questionnaires of the study. Exclusion criteria were prior gastrectomy, psychiatric diseases or long-term psychiatric drug addiction, presence of neoplastic or other serious concomitant diseases, history of intolerance to benzodiazepines. On the whole, two hundred and eighty patients were asked to enter the study, and 228 of them were accepted. The patients were randomly assigned to four groups by a computer procedure. In the control group (Co-group), EGD was performed with topical pharyngeal anesthesia alone (100 g/L lidocaine spray). In the other three groups the following methods were used in addition to pharyngeal anesthesia: conscious sedation with i.v. midazolam 35 μg/kg (Mi-group); presence of a relative in the endoscopy room throughout the procedure (Re-group); additional information about the procedure using a videotape lasting for about 10 min (Vi-group).

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of our hospital, and all patients gave their written consent to participate in the study.

Patients' assessments

Anxiety Since the anxiety experienced by patients undergoing EGD was hypothesized to be a factor related to potential discomfort, anxiety was measured by the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)[20] in the validated Italian language version[21]. Patients were asked to complete STAI before EGD. STAI is a 40-item questionnaire designed to measure state anxiety and trait anxiety. State anxiety is a temporary and situational anxiety, and trait anxiety is the tendency to awaken state anxiety under stress. Both kinds of anxiety were scored in the range of 20 to 80 points, a higher score indicated a greater anxiety. Before EGD, the patients had also to specify what they dreaded more about endoscopic examination, choosing among five items: fear of pain, fear of stifling, fear of complications, fear of endoscopic findings, and other.

Tolerance

Patients' assessment of tolerance to EGD was carried out at least 2 h after the end of the procedure. This interval was chosen to minimize the risk of persisting anterograde amnesia, which could potentially influence patient judgment. Patients assessed their tolerance answering the question: "how did you tolerate EGD?" ("well", "rather badly", "badly"), and rated the overall discomfort during EGD on an 100-mm visual analogue scale (0: no discomfort; 100: unbearable).

Endoscopist's assessment

All EGDs were carried out by the same endoscopist, using video endoscopes with a diameter of 9.8 mm (Fujinon video endoscopic system-Fujinon, Tokyo, Japan). Immediately after endoscopy, the operator recorded if EGD was completed, or it had to be interrupted, or it could be completed only after administration of sedatives (for Mi-group, after further sedatives in addition to midazolam previously administered). Moreover, he evaluated the ease of introduction of the instrument ("easy": no failed attempt of introduction; or "difficult": one or more failed attempts of introduction). Finally, he rated the discomfort caused to patients during EGD on an 100-mm visual analogue scale (0: no discomfort; 100: unbearable), and assessed the tolerance of the patients grading it into three steps: "good", "poor", "very bad".

Parameters monitored

Blood oxygen saturation (SaO2) and heart rate were continuously monitored during EGD. Desaturation was defined as a decrease in oxygen saturation below 90% for over 30 s. The occurrence of complications was recorded after each procedure. The duration of endoscopic examination was timed in all groups of patients. In Mi-group, the degree of sedation was evaluated using the Ramsay's scale[22].

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of patients in the four groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and chi-square test. Endoscopic findings, tachycardia, motives of fear, answers of patients to the questions about their tolerance to EGD, ease of introduction of the instrument, and endoscopist's evaluation of tolerance of patients to EGD were compared in the four groups by using chi-square-test.

State and trait pre-endoscopic anxiety levels, and the discomfort rated by the patients and endoscopist on the 100-mm visual analogue scale were analyzed using one-way and two-way ANOVA. Two-way ANOVA was also used to evaluate the influence of sex, age, and anxiety levels on the discomfort caused by EGD. Linear-regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between the state and trait anxiety scores, as well as the correlation between patients' and endoscopist's evaluation of the discomfort caused by EGD. A general linear model (GLM) procedure was used to analyze the influence of sex, age, groups of patients, state anxiety, duration of EGD, and endoscopic findings on the degree of discomfort caused by EGD, assessed by either the endoscopist or the patients.

Results were considered statistically significant if P values were < 0.05 (two-tailed test).

RESULTS

Two patients (1 in Co-group and 1 in Mi-group) were excluded from the study, as EGD was not completed. Two hundred and twenty-six patients (90 males and 136 females, mean age 38 ± 10.62 years, range 19-63 years) could be evaluated. The four groups did not differ in age, endoscopic findings, and duration of the examination. The male: female ratio was lower in Mi-group than in the other groups (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of the patients

| Co-group | Mi-group | Re-group | Vi-group | |

| Patients (n) | 62 | 52 | 58 | 54 |

| Gender (m/f) | 25/37 | 9/43a | 28/30 | 28/26 |

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 37.85 ± 10.44 | 40.13 ± 10.55 | 35.20 ± 10.57 | 39.24 ± 10.57 |

| State anxiety (mean ± SD) | 46.66 ± 10.73 | 54.19 ± 10.89b | 46.03 ± 11.42 | 39.62 ± 9.05 |

| Trait anxiety (mean ± SD) | 38.30 ± 7.16 | 44.26 ± 9.43b | 37.22 ± 8.21 | 38.05 ± 9.63 |

| Duration of EGD (seconds; mean ± SD) | 145.88 ± 45.18 | 157.40 ± 48.09 | 140.60 ± 35.56 | 142.96 ± 39.11 |

| Endoscopic findings (No cases): | ||||

| Normal findings | 30 | 25 | 26 | 22 |

| Esophagitis | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 |

| Hiatus Ernia | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Gastritis or Duodenitis | 24 | 19 | 19 | 14 |

| Gastric or duodenal ulcer | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Cancer | - | - | - | 1 |

| Other findings | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.001 vs the other three groups.

Fourteen point five percent of patients in Co-group (6/62), 21.1% in Mi-group (11/52), 20.6% in Re-group (12/58), 16.6% in Vi-group (9/54) had a heart rate higher than 100 beats/min before starting EGD. During EGD, the heart rate exceeded 130 beats/min for at least 30 seconds in 5, 2, 3, and 2 patients in the four groups, respectively. No complication occurred, and no case of oxygen desaturation was observed. According to Ramsay's scale, in Mi-group grade 2 sedation was reached in 50 patients, and grade 3 in 2 patients.

State anxiety scores before EGD were significantly higher in Mi-group than in the other groups (P < 0.001), as well as trait anxiety scores (P < 0.001) (Table 1). State and trait anxiety scores were strongly correlated (P < 0.001).

In all groups the most frequent cause of fear before EGD was the fear of stifling (70 cases on the whole). The ease of introduction of gastroscope did not differ among the four groups, and the introduction resulted in difficulty just in one patient of Co-group and in 3 of Vi-group.

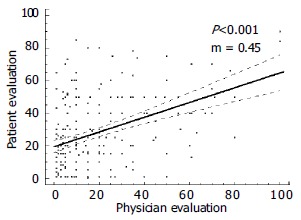

On the basis of patients' assessment, the tolerance to EGD was more frequently good when sedation was given: 80.7% of patients in Mi-group tolerated well gastroscopy, vs 43.5% in Co-group, 58.6% in Re-group, and 50% in Vi-group (P < 0.01) (Table 2). Conversely, no significant difference among the four groups was observed in the evaluation of the endoscopist, who nevertheless found that the discomfort caused by EGD was lower in Mi-group than in Co-group (P < 0.05) (Table 3). The degree of discomfort was lower in patients of Mi-group than in those of Co-group, but the difference was just close to threshold of significance, but did not reach it (P = 0.059) (Table 3). The other comparisons among the groups did not show any difference in the degree of discomfort caused by EGD. The evaluations of the patients and those of the endoscopist were strongly correlated (P < 0.001, m = 0.45), even though the endoscopist underestimated the degree of discomfort (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Tolerance to EGD and patients’ and endoscopist’s assessment

|

Patients’ assesmentb |

Endoscopist’s assessment |

|||||||

| Co-G (n) | Mi-G (n) | Re-G (n) | Vi-G (n) | Co-G (n) | Mi-G (n) | Re-G (n) | Vi-G (n) | |

| Good | 27 | 42b | 34 | 27 | 45 | 44b | 54 | 42 |

| Poor | 31 | 10b | 23 | 23 | 12 | 7b | 4 | 7 |

| Very bad | 4 | 0b | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1b | 0 | 5 |

Mi-G:

P < 0.01 vs the other three groups.

Table 3.

Discomfort caused to patients during EGD and patients’ and endoscopist’s assessment (visual analogue scale)

| Co-G (mean ± SD) | Mi-G (mean ± SD) | Re-G (mean ± SD) | Vi-G (mean ± SD) | |

| Patient evaluation | 33.01 ± 22.12 | 21.98 ± 21.60 | 29.17 ± 22.95 | 26.12 ± 21.94 |

| Endoscopist evaluation | 23.51 ± 22.99 | 14.17 ± 18.07a | 16.43 ± 14.42 | 20.81 ± 24.04 |

P < 0.05 vs Co-G.

Figure 1.

Linear regression of discomfort assessed by patients and endoscopist.

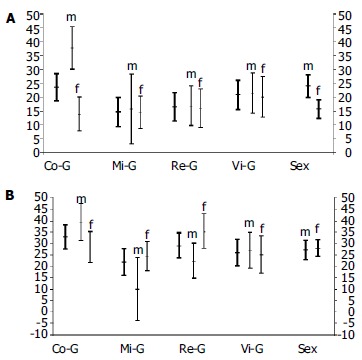

Two-way ANOVA performed on the degree of discomfort assessed by the patients, evaluated for factors "gender" and "groups of patients" corrected for age, trait anxiety and state anxiety, showed an inverse influence of the age (i.e. better tolerance for older individuals, P < 0.001) and the factor "groups of patients" (P < 0.05). Conversely, the degree of discomfort assessed by the endoscopist was significantly influenced by the factors "gender" and "groups of patients" (P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively). The factors "gender" and "groups of patients" showed a true and constant interaction (interaction factor P < 0.01), reflecting behaviors significantly different between males and females within the four groups, in particular in Co-group (Figures 2A, B).

Figure 2.

Discomfort assessed by patients and andoscopist, and mean values for factors "groups of patients" and "gender" with 95% c.l. Thick lines: m = males; f = females. Co-G: control group Mi-G: midazolam group Re-G: relatives group Vi-G: video group A: Discomfort assessed by patients B: Discomfort assessed by endoscopist.\

Also the GLM procedure showed that age exerted the greatest influence on the discomfort caused by EGD in opinion of the patients (inverse correlation, P < 0.001), whereas in opinion of the endoscopist the discomfort was mainly influenced by the gender (females tolerated EGD better than males, P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Influence of some parameters on degree of discomfort caused by EGD (GLM procedure)

| Parameter |

Patient’s assessment |

Endoscopist’s assessment |

||||

| Coefficient | SE | P | Coefficient | SE | P | |

| Gender | -0.251 | 3.153 | 0.937 | -10.094 | 2.901 | 0.001 |

| Age (yr) | -0.621 | 0.140 | 0.000 | -0.159 | 0.129 | 0.219 |

| Groups of patients | -1.138 | 1.325 | 0.391 | -1.012 | 1.219 | 0.407 |

| State anxiety | 0.104 | 0.136 | 0.445 | 0.237 | 0.126 | 0.060 |

| Time for EGD | 0.046 | 0.039 | 0.237 | -0.057 | 0.036 | 0.112 |

| Endoscopic findings | -0.813 | 1.774 | 0.647 | 3.158 | 1.632 | 0.054 |

DISCUSSION

Although conscious sedation is the method most widely used to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing EGD, its actual role is still an unresolved problem. Very large differences in sedation practice existed among different countries, and sometimes among different units within the same country[5]. To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial comparing the efficacy in improving the tolerance to EGD of conscious sedation, the presence of a relative in the endoscopy room throughout the procedure, and additional information by using a videotape. Abuksis et al[23] demonstrated that previous endoscopy experience could reduce anxiety level and influence patients' compliance, and other authors identified endoscope size as a significant variable in determining tolerance to the procedure[24,25]. For these reasons, in our study all patients enrolled had no prior endoscopy experience, and all EGDs were carried out using gastroscopes with the same diameter.

Our results suggested that low-dose conscious sedation with midazolam could improve the tolerance to EGD, according to a previous trial reporting a lower discomfort in sedated patients than in controls[26]. Conversely, the presence of a relative attending the procedure and the use of informative videotape did not seem to give the patients significant advantages over the controls. However, better tolerance and lower discomfort were found in Re-group and Vi-group than in Co-group by either the patients or the endoscopist. Although these findings did not reach the significance level, in our opinion they suggested that the method used in controls (pharyngeal anesthesia only) was the worst approach to perform EGD. Indeed, the multivariate analysis showed constant differences among the groups of patients in concern of the discomfort caused by endoscopy, highlighting the usefulness of preparatory interventions in improving the tolerance to EGD.

The presence of relatives has been proved helpful in several medical fields, such as to children during hospitalization and to women during childbirth[27], but it is not a standard procedure in digestive endoscopy. At present, just one randomized study was published on this topic, and the results suggested that the presence of a family member throughout endoscopy could represent a promising approach[12]. Conversely, the usefulness of additional information to reduce the anxiety and to improve the compliance of patients has been widely investigated, but with conflicting results. Detailed information before endoscopy has been reported to reduce anxiety levels[11,28], but other studies failed in demonstrating any usefulness of this approach[29], and some authors found that the over-information about endoscopy could even increase anxiety levels[30,31].

The evaluation of the discomfort expressed by the patients and the endoscopist showed a strong correlation in our study (Figure 1). However, the endoscopist rated the patient degree of discomfort as lower than the patients themselves. According to the observation of Watson et al[32] that both endoscopists and nurses underestimated the discomfort felt by the patients. Besides anxiety, in our experience age and gender also influenced significantly the tolerance to endoscopy. Indeed, high levels of discomfort during EGD have been recently reported to be associated with younger age and high levels of pre-endoscopic anxiety[24]. Older patients were likely to tolerate endoscopy better than their younger counterparts as they had a decreased pharyngeal sensitivity[33,34]. Unlike several studies reporting better tolerance in men[26,35], we found that female gender was associated with better tolerance. However, this gender-specific finding has been disputed by other authors[3,24,33].

Despite the effectiveness of conscious sedation shown in our study, we think it should be avoided whenever possible in clinical practice. The extensive use of sedation would require several extra-charges, including the cost of drugs, prolongation of the procedure time, need of monitoring cardiopulmonary functions, need of recovery room for post-procedure observation, and the impossibility for patients to return to work immediately after endoscopic examination[36]. Furthermore, sedative drugs are not free of adverse effects. In our series, no complications and oxygen desaturation were observed, and low-dose midazolam induced just rarely significant alterations in cardiorespiratory parameters[26]. Nevertheless, conscious sedation could cause hypoxemia, which may induce cardiopulmonary complications, and most complications associated with endoscopy were attributable to the medications given for the procedure rather than the procedure itself[13-15]. For these reasons, we think that further studies incorporating cut-off points are necessary to identify the patients who are likely to tolerate diagnostic gastroscopy without sedation. Some other preparatory interventions might also be effective to reduce endoscopy-related anxiety[37]. The intervention techniques we used might be incorporated into our endoscopic practice, as they are simple, quick, easy to reproduce, and their extensive use doesa not require additional extra-charges, and expose the patients to the risk of complications.

Footnotes

Edited by Wang XL Proofread by Xu FM

References

- 1.al-Atrakchi HA. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy without sedation: a prospective study of 2000 examinations. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:79–81. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(89)72712-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt LJ. Patients' attitudes and apprehensions about endoscopy: how to calm troubled waters. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:280–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, Calvet X, Moix J, Rué M, Roqué M, Donoso L, Bordas JM. Identification of factors that influence tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:201–204. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199902000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominitz JA, Provenzale D. Patient preferences and quality of life associated with colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2171–2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell GD. Premedication, preparation, and surveillance. Endoscopy. 2002;34:2–12. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-19389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattuso SM, Litt MD, Fitzgerald TE. Coping with gastrointestinal endoscopy: self-efficacy enhancement and coping style. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:133–139. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woloshynowych M, Oakley DA, Saunders BP, Williams CB. Psychological aspects of gastrointestinal endoscopy: a review. Endoscopy. 1996;28:763–767. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conlong P, Rees W. The use of hypnosis in gastroscopy: a comparison with intravenous sedation. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:223–225. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.882.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bampton P, Draper B. Effect of relaxation music on patient tolerance of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:343–345. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li CK, Nauck M, Löser C, Fölsch UR, Creutzfeldt W. [Acupuncture to alleviate pain during colonoscopy] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1991;116:367–370. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luck A, Pearson S, Maddern G, Hewett P. Effects of video information on precolonoscopy anxiety and knowledge: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:2032–2035. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)10495-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapira M, Tamir A. Presence of family member during upper endoscopy. What do patients and escorts think. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:272–274. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199606000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herman LL, Kurtz RC, McKee KJ, Sun M, Thaler HT, Winawer SJ. Risk factors associated with vasovagal reactions during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:388–391. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iber FL, Sutberry M, Gupta R, Kruss D. Evaluation of complications during and after conscious sedation for endoscopy using pulse oximetry. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:620–625. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mokhashi MS, Hawes RH. Struggling toward easier endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:432–440. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazzaroni M, Bianchi Porro G. Preparation, premedication and surveillance. Endoscopy. 1998;30:53–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulcahy HE, Hennessy E, Connor P, Rhodes B, Patchett SE, Farthing MJ, Fairclough PD. Changing patterns of sedation use for routine out-patient diagnostic gastroscopy between 1989 and 1998. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:217–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedenbro JL, Lindblom A. Patient attitudes to sedation for diagnostic upper endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1115–1120. doi: 10.3109/00365529109003964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira S, Hussaini SH, Hanson PJ, Wilkinson ML, Sladen GE. Endoscopy: throat spray or sedation. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1994;28:411–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo-Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Questionario di autovalutazione per l'ansia di stato e di tratto. Manuale di istruzioni. Traduzione di Lazzari R, Pancheri P. Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. Br Med J. 1974;2:656–659. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5920.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abuksis G, Mor M, Segal N, Shemesh I, Morad I, Plaut S, Weiss E, Sulkes J, Fraser G, Niv Y. A patient education program is cost-effective for preventing failure of endoscopic procedures in a gastroenterology department. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1786–1790. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulcahy HE, Kelly P, Banks MR, Connor P, Patchet SE, Farthing MJ, Fairclough PD, Kumar PJ. Factors associated with tolerance to, and discomfort with, unsedated diagnostic gastroscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1352–1357. doi: 10.1080/003655201317097245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulcahy HE, Riches A, Kiely M, Farthing MJ, Fairclough PD. A prospective controlled trial of an ultrathin versus a conventional endoscope in unsedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2001;33:311–316. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froehlich F, Schwizer W, Thorens J, Köhler M, Gonvers JJ, Fried M. Conscious sedation for gastroscopy: patient tolerance and cardiorespiratory parameters. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:697–704. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gjerdingen DK, Froberg DG, Fontaine P. The effects of social support on women's health during pregnancy, labor and delivery, and the postpartum period. Fam Med. 1991;23:370–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lembo T, Fitzgerald L, Matin K, Woo K, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. Audio and visual stimulation reduces patient discomfort during screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1113–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy N, Landmann L, Stermer E, Erdreich M, Beny A, Meisels R. Does a detailed explanation prior to gastroscopy reduce the patient's anxiety. Endoscopy. 1989;21:263–265. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawes PJ, Davison P. Informed consent: what do patients want to know. J R Soc Med. 1994;87:149–152. doi: 10.1177/014107689408700312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tobias JS, Souhami RL. Fully informed consent can be needlessly cruel. BMJ. 1993;307:1199–1201. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6913.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watson JP, Goss C, Phelps G. Audit of sedated versus unsedated gastroscopy: do patients notice a difference. J Qual Clin Pract. 2001;21:26–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1762.2001.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abraham N, Barkun A, Larocque M, Fallone C, Mayrand S, Baffis V, Cohen A, Daly D, Daoud H, Joseph L. Predicting which patients can undergo upper endoscopy comfortably without conscious sedation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:180–189. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies AE, Kidd D, Stone SP, MacMahon J. Pharyngeal sensation and gag reflex in healthy subjects. Lancet. 1995;345:487–488. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90584-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan CC, Freeman JG. Throat spray for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is quite acceptable to patients. Endoscopy. 1996;28:277–282. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitt CM. Preparation for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: opportunity or inconvenience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:430–432. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hackett ML, Lane MR, McCarthy DC. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: are preparatory interventions effective. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:341–347. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]