Abstract

AIM: Achalasia is the best known primary motor disorder of the esophagus in which the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) has abnormally high resting pressure and incomplete relaxation with swallowing. Pneumatic dilatation remains the first choice of treatment. The aims of this study were to determine the long term clinical outcome of treating achalasia initially with pneumatic dilatation and usefulness of pneumatic dilatation technique under endoscopic observation without fluoroscopy.

METHODS: A total of 65 dilatations were performed in 43 patients with achalasia [23 males and 20 females, the mean age was 43 years (range, 19-73)]. All patients underwent an initial dilatation by inflating a 30 mm balloon to 15 psi under endoscopic control. The need for subsequent dilatation was based on symptom assessment. A 3.5 cm balloon was used for repeat procedures.

RESULTS: The 30 mm balloon achieved a satisfactory result in 24 patients (54%) and the 35 mm ballon in 78% of the remainder (14/18). Esophageal perforation as a short-term complication was observed in one patient (2.3%). The only late complication encountered was gastroesophageal reflux in 2 (4%) patients with a good response to dilatation. The mean follow-up period was 2.4 years (6 mo - 5 years). Of the patients studied, 38 (88%) were relieved of their symptoms after only one or two sessions. Five patients were referred for surgery (one for esophageal perforation and four for persistent or recurrent symptoms). Among the patients whose follow up information was available, the percentage of patients in remission was 79% (19/24) at 1 year and 54% (7/13) at 5 years.

CONCLUSION: Performing balloon dilatation under endoscopic observation as an outpatient procedure is simple, safe and efficacious for treating patients with achalasia and referral of surgical myotomy should be considered for patients who do not respond to medical therapy or individuals that do not desire pneumatic dilatations.

INTRODUCTION

Achalasia is an uncommon disorder of the esophagus characterized by clinical, radiologic and manometric findings. Dysphagia, regurgitation, weight loss and chest pain are among the most recognized clinical features of the disease. Manometrically it is distinguished by esophageal aperistalsis and incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Esophageal dilatation and a tapered deformity of the distal esophagus are presumably late radiological manifestations of the disease[1,2]. The pathogenesis of achalasia remains unknown. Available data suggest hereditary, degenerative, autoimmune and infectious factors as possible causes for achalasia, the latter two are the most commonly accepted possible etiologies. The mean age of onset varies between 30 and 60 years with a peak incidence in the fifth decade. The incidence is 1.1 per 100000 with a prevalence of 7.9 to 12.6 per 100000[2,3].

Although there is no definite cure for achalasia, the goals of treatment should be: 1) relieving the patient's symptoms, 2) improving esophageal emptying and 3) preventing development of a megaesophagus. The optimal treatment of achalasia includes several options and presents a challenge for most gastroenterologists. It can be treated by botulinum toxin injection, pneumatic dilatation or esophagomyotomy, but the most effective treatment options are graded pneumatic dilatation and surgical myotomy. All of these therapeutic modalities are aimed at removing the functional barrier at the lower esophageal sphincter level. Although high success rates have been reported for these therapeutic modalities, the fact remains that the esophageal propulsive force is not usually restored and therefore it is conceivable that a normal esophageal function can never be expected among these patients[2,4,5].

The aim of our study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of graded pneumatic dilation using two different size (3.0 and 3.5 cm) balloon dilators (Rigiflex) in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. We hereby report our experience, which indicates that pneumatic dilatation can be safely performed under direct endoscopic observation without fluoroscopic guidance and with only a short-term clinical monitoring in an outpatient setting prior to discharge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Forty-three consecutive patients (23 males and 20 females) were evaluated. The ages ranged from 19 to 73 years with a mean age of 43 years. All patients were referred because of typical symptoms of achalasia. All had dysphagia, but some also had regurgitation or pulmonary aspiration (Table 1). The diagnosis of achalasia was made on the basis of clinical, radiologic and manometric criteria. Barium esophagogram showed a distal narrowing of the esophagus (bird beak deformity) and variable degrees of dilation of the esophagus in most patients (93%). Mean esophagus diameter was 3.8 cm (range, 2-6.3 cm). Upper endoscopy was done in all patients to exclude secondary causes of achalasia. Computerized tomography of the chest was done in 12 patients over age 40 with significant weight loss over a short period (six months or less) to exclude mediastinal malignancy causing pseudoachalasia.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and demographic data of patients [mean ± SD, (min-max)]

| Age (yr) | 44 ± 16 (19-73) |

| Gender (M/F) | 23/20 |

| Dysphagia | 43 (100%) |

| Chest pain | 5 (11%) |

| Regurgitation | 34 (79%) |

| Pulmonary aspiration | 9 (21%) |

| Mean duration of symptoms (mo) | 35 ± 21 (6-72) |

| Mean weight loss (kg) | 7.7 ± 2 (4-11) |

| LES pressure (mmHg) | |

| Before dilation | 38.6 ± 12 (19-66) |

| After dilation | 11.8 ± 8 (0-16) |

| Vigorous achalasia | 1 (2.3%) |

| Esophagus diameter (cm) | 3.8 (2-6.5) |

Eligibility criteria for entry into the study required: a diagnosis of achalasia by manometry as defined above, absence of obstructive intrinsic or extrinsic esophageal lesions by X-ray and endoscopy, and Absence of esophageal or gastric carcinoma, a peptic stricture or a prior surgical fundoplication.

Symptoms of the patients were scored using a questionnaire requesting information regarding the presence and severity of their difficulty in swallowing solids and liquids on a 5 point subjective visual scale: 0 = no symptoms, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, 4 = very severe.

Esophageal manometry

Esophageal manometry was performed in all patients with a four lumen polyvinyl catheter with Dent sleeve working with a pneumohydraulic capillary perfusion system (Synectic PC polygraph- Gastrosoft Inc.Upper GI edition, version 6.0). Manometric examinations were performed by the same author. LES was localised using the station pull-through technique. Other three orifices, located 5 cm apart and also oriented at 90o angles, for determination of the peristalsis and pressures, by placing the distal orifice 5 cm above the LES. The peristalsis was measured with 10 wet swallows of 5 mL of water, each at intervals of 60 s or more. Aperistalsis was the absolute manometric criteriron required for the diagnosis of achalasia with increased LES pressure and incomplete/absent relaxation were the complementary findings[7]. Incomplete relaxation was defined as the failure of LES pressure to drop to gastric baseline during a dry and /or wet swallow (Figure 1).

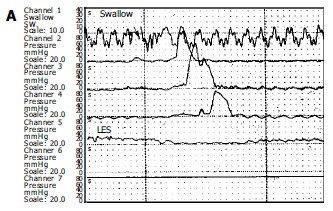

Figure 1.

Manometric samples from a normal individual (A) and a patient with achalasia (B). Figure A illustrates the normal peristaltic activity forwarding at cranio-caudal direction whereas figure B shows typical manometric findings of achalasia. Note the aperistalsis, weak and simultaneous contractions (mirror sign), and incomplete LES relaxation after swallow. Basal LES pressure is high (40 mmHg).

Technique of pneumatic dilation

All dilations were performed on outpatients. Dilations were done by the same authors using the Rigiflex achalasia balloon dilators (Microvasive) in a graded manner. A 3.0 cm dilator was always used first. If there was still no symptomatic response, a 3.5 cm dilator was used after 6-8 wk. After clear liquid diet for 24 h and an overnight fast, an endoscope (Pentax EG-2940) was passed after application of a local anesthetic to the pharynx under conscious sedation (Midazolam 0.04 mg/kg iv) to evacuate the residual liquid from the esophagus and to insert a guide wire. The guide wire was placed into the duodenum via stomach under endoscopic guidance and endoscope was removed. A Rigiflex balloon dilator, which was marked with a thick coloured marker at the mid section of the balloon was passed over the guidewire to stomach and slightly inflated (less than 5 psi) to get a soft tube shaped form. Endoscope was reinserted and positioned proximally to adjust and control the position of the balloon in the esophagus. Balloon was withdrawn to esophagus and marked part of the balloon was located within the gastroesophageal junction under endoscopic control (Figure 2). The balloon was then inflated until 15 psi. and inflation was maintained for 60 s. Ischemic ring at the lower esophageal sphincter level was seen during dilatation through the transparent balloon. After repeating of the same inflation procedure one more time at the same session endoscopic dilatation was terminated and endoscope, balloon and guidewire were removed. Balloon dilator surface was checked to see if there was blood on it. The procedure was well tolerated by all patients.

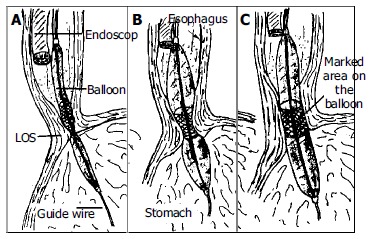

Figure 2.

Technique for pneumatic dilatation under endoscopic control without fluoroscopy. The balloon was positioned so that its midsection was at the high pressure level (A). The balloon was inflated and the endoscopist observes with endoscope proximally to balloon (B). With successful dilatation the ischemic ring of dilated segment was diminished or disappeared (C).

The severity of chest pain in patients was scored after the balloon dilation on a scale of 0-10 (0, absence of pain; 10 severest pain). Gastrograffin swallow was done few hours after dilation to exclude esophageal perforation. After an observation period of 6 h, patients were discharged and permitted to eat the next morning.

Second esophageal manometry and symptom scoring were performed in all patients with therapeutic response six weeks after pneumatic dilation to evaluate the efficacy of endoscopic balloon dilation.

The response to balloon dilation was considered excellent if there was no or very rare mild dysphagia, good if there was intermittent mild dysphagia, or poor if there was persistent daily mealtime dysphagia. The balloon therapy was considered successful if the patients had a good or excellent response.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as either percentages or mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Chi-square test, Kendall's tau-b coefficient and Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The cumulative remission rates of the patients treated with balloon dilation were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and the difference between treatment groups was tested by the log rank test.

RESULTS

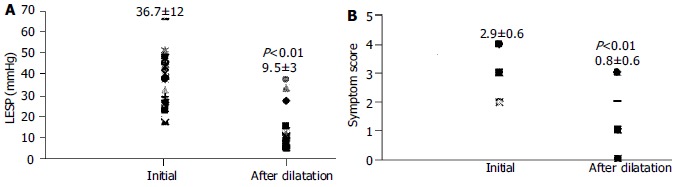

The clinical characteristics and demographic data of patients are shown in Table 1. The mean LES pressure was 37.6 ± 12 mmHg. Relaxation failure of LES and aperistalsis with low amplitude simultaneous uniformed waves were present in all patients. Only one of the 5 patients with retrosternal pain was diagnosed as a vigorous achalasia (2.3%) at esophageal manometry. The LES pressures and symptom scores of successfully dilated patients were decreased significantly one month after dilation, (37.6 ± 12 vs 9.5 ± 3) and (2.9 ± 0.6 vs 0.8 ± 0.6) respectively (P < 0.01) (Figure 3). There was no significant correlation between the parameters of age, sex, initial LES pressure, symptom score and barium study findings.

Figure 3.

Lower esophageal sphincter pressures (LESP) (A) and symptom scores (B) of patients with therapeutic response initially and at one month after pneumatic dilatation.

Chest pain was reported by all patients during the initial dilation, with a mean pain score of 7.2 ± 2.3 (range, 4-10). Chest pain score was 8.1 ± 1.8 in patients who were successfully dilated at the first session although score was 4.8 ± 2.1 in patients with a poor response to initial balloon dilation (P < 0.05). Chest pain after the procedure usually lasted for 30-60 min and was substernal in nature, diminishing gradually over time and resolved completely within 2 to 6 h.

The results of balloon dilation are summarized in Table 2. A total of 65 dilatations were performed in 43 patients for an average of 1.7 dilations per patient. The 3 cm balloon was always used first. Twenty-four patients (56%) were successfully dilated with a 3 cm balloon only. Fourteen patients had an excellent response (32.5%) and 10 patients had a good response (23%) to 3.0 cm balloon dilation. Old age at the time of initial pneumatic dilatation was significantly associated with a better clinical response to treatment as assessed by the need for subsequent treatments (Kendall's tau-b = 0.414, P = 0.016) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Results of rigiflex balloon dilation under endoscopic control

| Inflation pressure (psi) | 15 |

| Dilation time per session (s) | 2 × 60 |

| Success with 3.0 cm balloon | 24/42(56%) |

| Success with 3.5 cm balloon | 14/18(78%) |

| Overall success rate at first year1 | 19/24(80%) |

| Overall success rate at 5 years1 | 7/13(54%) |

| Complications | |

| Perforation | 1(2.3%) |

| Bleeding | - |

| Mortality | - |

Among the patients whose long term follow up information was available.

Table 3.

Effect of age, LES pressure and esophageal diameter on the clinical benefit of the initial pneumatic dilation. 1With 3 cm balloon

| Patients with successful initial pneumatic dilation (n = 24) | Patients with successful initial pneumatic dilation (%) | P | |

| Age (yr) | |||

| < 35 | 4/14 | 28 | < 0.01 |

| 35-55 | 11/17 | 65 | |

| > 55 | 9/11 | 82 | |

| LES pressure (mmHg) | |||

| < 30 | 6/12 | 50 | |

| 30-45 | 13/21 | 62 | NS |

| > 45 | 5/9 | 55 | |

| Esophageal diameter (cm) | |||

| < 3 | 4/7 | 57 | |

| 3-4 | 11/21 | 52 | NS |

| > 4 | 9/14 | 64 |

NS: Non significant.

Eighteen patients (42%) with a poor response to 3.0 cm balloon were dilated with a 3.5 cm balloon at intervals of 6-8 wk. Nine patients had excellent, five had good and four patients had poor response to the second dilation with a 3.5 cm balloon. Patients with a poor response to the second dilation with a 3.5 cm balloon were dilated with a 3.5 cm balloon at the third time but all of them were symptomatic after a while and these patients were no longer treated with a larger balloon (4 cm), instead, surgical treatment was suggested. One patient who refused surgery had repeated dilation every 6 to 12 mo with a 3.5 cm balloon due to symptom recurrence.

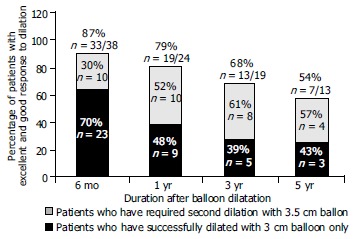

The mean follow-up period in the entire group was 2.4 years (range, 6 mo-5 years). Among the 38 patients whose long term follow up information was available, 33 (87%) at six months were asymptomatic [Among them 23 (70%) required once and 10 (30%) required twice dilation]. At the end of the first year, 16 of 24 patients (66%) whose follow up information was available were asymptomatic. Among the 24 patients, 3 (12.5%) complained of mild intermittent dysphagia and 5 (21%) had intermittent severe dysphagia. The total number of asymptomatic patients and patients with mild dysphagia was 19 (79%) at the end of the first year. Among these, 10 patients (52%) required a second dilation.

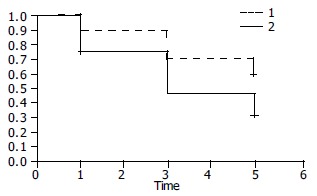

Among patients whose follow up information was available at 3 years the 19, 13 were in remission (68%) (5 asymptomatic and 8 with intermittent mild dysphagia). Among patients whose follow up information was available at 5 years the 13, 7 were in remission (54%) (3 were asymptomatic and 4 with mild intermittent dysphagia). Among the total, 3 patients (44%) required once and 4 (56%) required twice dilation (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the Kaplan-Meier plot for the two treatment groups of patients who were dilated once or twice. The cumulative one, three and five year remission rates were higher in patients dilated twice but this difference was not statistically significant (Log-rank χ2 = 2.10, P = 0.1471).

Figure 4.

Percentage of patients with excellent and good response to dilatation at 6 mo, 1, 3 and 5 years.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier plot for the two treatment groups of patients who were dilated once2 or twice1. The cumulative one, three and five year remission rates were higher in patients dilated twice but this difference was not statistically significant (Log-rank χ2 = 2.10, P = 0.1471).

Gastrograffin swallow done immediately after balloon dilation revealed esophageal perforation in one patient (2.3%) (a 60 years old female) with persistent chest pain and surgical therapy was required. There were no other immediate complications. Reflux esophagitis as a late complication was observed in two of the patients who had a good response to dilatation during the follow up period (4%).

Blood on the balloon after dilatation was a common finding. There was no statistically significant correlation between bloody dilator and dilatation success (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study analysed the effectiveness of pneumatic balloon dilation and the clinical outcome in patients with achalasia. Our results showed that once or twice pneumatic dilatation provided good results in the majority of patients with achalasia and long term results were 79% at 1 year and 54% at 5 years. Of the patients studied, 38 (88%) were relieved of their symptoms after one or two sessions. An initial pneumatic dilation was an effective single treatment with no further treatment needed in 57% of patients in a short term period. The remaining 43% of patients treated initially with pneumatic dilation needed additional treatments due to persistent or recurrent symptoms and only 11% of patients failing pneumatic dilatation were referred for surgery (4 with poor response to repeated dilations and 1 with perforation due to dilation). Four patients with a poor response to the second dilation with a 3.5 cm balloon were dilated with a 3.5 cm balloon the third time but all of them were symptomatic after a while and these patients were not treated with a larger balloon. Some studies have reported using a 3.5 cm balloon instead of a 3 cm balloons one as the initial balloon but others have used 3 cm for the initial dilatation[8,9,11]. In our series application of the second pneumatic dilation increased the long term clinical benefit of pneumatic dilation from 30% at six months to 57% at 5 years, but this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Figure 4). To some extent, our results about the clinical benefit of a single pneumatic dilatation and the use of the second dilatation for patients with persistent symptoms are in agreement with other studies. It has been shown that the overall efficacy of endoscopic balloon dilation was approximately 85%, with an excellent to good response for 3, 3.5 and 4 cm dilators being 70%, 87% and 93% respectively (9 studies; four prospective, five retrospective, 261 patients, a mean follow up of 1.9 years (range; 0.3 to 6 years)[10-17] (Table 4). Approximately 50% (range, 17% to 75%) of all patients required repeat dilations, equaling to 1.2 to 2 dilations per patient. About one half of patients responded to a repeat dilation, with the remainder either proceeding to surgical management or deciding to live with their persistent symptoms. The reported overall long-term efficacy of pneumatic dilatation was 50%-90% at 1 year and 60% at 5 years[1]. The major adverse event with pneumatic dilatation was esophageal perforation with a 2% cumulative rate. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has recommended that if a single dilation session (size of the balloon dilator unspecified) does not produce satisfactory relief, a second attempt may be warranted and if this fails, surgery usually is indicated[15].

Table 4.

Cumulative effectiveness of graded pneumatic dilators for achalasia

| Author | Pt. # | Study design | Dilator % (size/cm) | Decrease of LESP | % Improvement Excellent/Good | Follow-up (yr) Mean (range) | Perforation (%) |

| Barkin(11) | 50 | Prospec. | 3.5 | - | 90 | 1.3 (1–3.4) | 0 |

| Levine(12) | 62 | Retrosp. | 3-3.5 | - | 85-88 | - | 0 |

| Wehrmann(15) | 40 | Retrosp. | 3–3.5 | 42 | 89 | 2–5 | 2.5 |

| Lee(9) | 28 | Prospec. | 3–3.5-4 | - | - | - | 7 |

| Gelfand(10) | 24 | Prospec. | 3–4 | 60-68 | 70–93 | - | 0 |

| Kadakia(13) | 29 | Prospec. | 3–3.5–4 | 67 | 62–79–93 | 4 (3–6) | 0 |

| Abid(14) | 36 | Retrosp. | 3.5–4 | - | 88–89 | 2.3 (1–4) | 6.6 |

| Lambroza(16) | 27 | Retrosp. | 3 | - | 67 | 1.8 (0.1–4.8) | 0 |

| Bhatnagar(17) | 15 | Prospec. | 3–3.5 | - | 73-93 | 1.2 (0.3–3) | 0 |

The patient population undergoing initial dilation in this study was not large enough to compare the effect of age on the dilation success, but our results indicate that initial pneumatic dilation was more effective in older patients (χ2 value: 8.215a, P = 0.016, Kendall's tau-b 0.414, P = 0.001). This increased clinical benefit of pneumatic dilation in old patients has also been described by other investigators[19,21,22]. There was no significant difference between the mean ages of the patients with and without remission at the end of 1 and 5 years although the patients in remission at 5 years were older, [43 ± 16 (n = 19) vs 48 ± 16 (n = 5) (P > 0.05) at 1 year and 53 ± 17 (n = 7) vs 37 ± 14 (n = 6) (P > 0.05), at 5 years respectively]. The efficacy of pneumatic dilatation was not influenced by initial LES pressure and esophageal diameter (Table 3).

After balloon dilation, the mean LES pressure was 11.8 ± 4 mmHg (range, 0-16 mmHg) and it represented 75% decrease of basal LES pressure. It has been shown that basal LES pressure decreased from 39% to 68% after dilation but these changes did not allways indicate a dilation success. In general, a decrement in LES pressure of more than 50% or an absolute end-expiratory LES pressure of less than 10 mmHg were more indicative of clinical success[2]. Timed barium esophagogram or scintigraphy may correlate with symptomatic improvement in up to 72% of patients. In spite of this similarity, approximately one third of patients who noted complete relief showed less than 50% improvement in barium column height and esophageal diameter[21].

Only one of 43 patients in our series had an esophageal perforation during treatment with pneumatic dilatation (2.3%). This complication rate is similar to those reported by other experienced groups[9,19,20]. Gradual increase in dilator size based on symptomatic response and the use of inflation pressure between 10 to 15 psi can minimize the risk of perforation. Esophageal perforation may occur in up to 5% of all reported cases, with a possible increased risk if hiatal hernia is present. In our study gastrograffin swallow was performed in all patients. Using immediate contrast studies to exclude perforation became routine in the late 1970's, and using this approach has been recommended in several studies and text books. Some authors suggested that contrast studies were indicated only when there was clinical suspicion of perforation. It has been reported that an immediate contrast study may not always exclude a perforation which may become clinically evident several hours later[5].

Less commonly, intramural hematoma, diverticula at gastric cardia, mucosal tears, reflux esophagitis, prolonged post-procedure chest pain, fever, hematemesis without changes in hematocrit and angina may occur after pneumatic dilatation. Objective assessment of gastroesophageal reflux after pneumatic dilation rarely has been studied. Abnormal 24 h pHscores have been documented in approximately 20% to 33% of patients after dilation. In spite of these abnormal scores, very few of these patients were symptomatic or developed endoscopic or clinical evidence of GERD related complications. It has been shown that postdilatation LES pressures and gastric emptying were similar between reflux and non-reflux groups[2]. Since GERD related symptoms correlated poorly in achalasia patients, 24 h pH monitoring has been recommended for patients that developed frequent heartburn, reflux or chest pain in spite of an otherwise good clinical response to dilation. One of the important points of this study was the dilatation technique which did not require fluoroscopic control (see materials and methods). Our experience shows that Rigiflex balloon can be successfully positioned across the gastroesophageal junction and inflated under direct endoscopic observation. This technique is as effective as conventional fluoroscopic technique and has an advantage to prevent patients and endoscopists from an additional X-ray. Furthermore we have seen that patient tolerability was very good and success rates were reasonable and comparable with others. Safety and efficacy of pneumatic dilation for achalasia without fluoroscopic control also have been shown by Lambroza and Levine[16,18].

In a recently published interesting study, Cheng et al[23] evaluated the usefulness of temporariy placing of covered stents for 3-7 d versus pneumatic dilatation and found that the early and late (at one and three years respectively) relapse rates were quite low in the stent treated group versus the pneumatic dilatation treated one. The success of this method was suggested to be due to chronic tearing of the cardia muscularis which resulted in a diminished amount of fibrosis and so restenosis after the stent was withdrawn.

The results of our study suggest that pneumatic dilatation for achalasia without fluoroscopic guidance is a safe and effective treatment modality. A graduatl increase in dilator size based on symptomatic response minimizes complications. Symptomatic patients with achalasia who are good surgical candidates should be given an option of graded pneumatic dilatation before surgery. Although surgical myotomy, once with a high mortality and long hospital stay, can now be performed laparoscopically with a similar efficacy to the open surgical approach, reduced morbidity and hospitalization time, referral of myotomy should be considered for patients who do not respond to medical therapy or individuals that do not desire pneumatic dilatations. The advantages of pneumatic dilatation over surgical myotomy are a brief period of discomfort, a very short hospital stay and consequently low exposure.

Footnotes

Edited by Zhu LH and Wang XL Proofread by Xu FM

References

- 1.Clouse RE, Diamant NE. Esophageal motor and sensory function and motor disorders of the esophagus. In: Sleisenger MH, Friedman LS, Feldman M, editors. Eds: Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Philadelphia Saunders; 2002. pp. 561–598. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunaway PM, Wong RK. Achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s11938-001-0051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard PJ, Maher L, Pryde A, Cameron EW, Heading RC. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edinburgh. Gut. 1992;33:1011–1015. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Henríquez A, Cortés C. Late results of a prospective randomised study comparing forceful dilatation and oesophagomyotomy in patients with achalasia. Gut. 1989;30:299–304. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciarolla DA, Traube M. Achalasia. Short-term clinical monitoring after pneumatic dilation. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1905–1908. doi: 10.1007/BF01296116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakash C, Clouse RE. Esophageal motor disorders. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 1999;15:339–346. doi: 10.1097/00001574-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nair LA, Reynolds JC, Parkman HP, Ouyang A, Strom BL, Rosato EF, Cohen S. Complications during pneumatic dilation for achalasia or diffuse esophageal spasm. Analysis of risk factors, early clinical characteristics, and outcome. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1893–1904. doi: 10.1007/BF01296115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stark GA, Castell DO, Richter JE, Wu WC. Prospective randomized comparison of Brown-McHardy and microvasive balloon dilators in treatment of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1322–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter JE, Lightdale CJ. Management of achalasia. AGA Postgraduate Course, May 19-20. 2001 303-308. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelfand MD, Kozarek RA. An experience with polyethylene balloons for pneumatic dilation in achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:924–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barkin JS, Guelrud M, Reiner DK, Goldberg RI, Phillips RS. Forceful balloon dilation: an outpatient procedure for achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)70964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine ML, Moskowitz GW, Dorf BS, Bank S. Pneumatic dilation in patients with achalasia with a modified Gruntzig dilator (Levine) under direct endoscopic control: results after 5 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1581–1584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadakia SC, Wong RK. Graded pneumatic dilation using Rigiflex achalasia dilators in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abid S, Champion G, Richter JE, McElvein R, Slaughter RL, Koehler RE. Treatment of achalasia: the best of both worlds. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:979–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wehrmann T, Jacobi V, Jung M, Lembcke B, Caspary WF. Pneumatic dilation in achalasia with a low-compliance balloon: results of a 5-year prospective evaluation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambroza A, Schuman RW. Pneumatic dilation for achalasia without fluoroscopic guidance: safety and efficacy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1226–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatnagar MS, Nanivadekar SA, Sawant P, Rathi PM. Achalasia cardia dilatation using polyethylene balloon (Rigiflex) dilators. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1996;15:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine ML, Dorf BS, Moskowitz G, Bank S. Pneumatic dilatation in achalasia under endoscopic guidance: correlation pre- and postdilatation by radionuclide scintiscan. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parkman HP, Reynolds JC, Ouyang A, Rosato EF, Eisenberg JM, Cohen S. Pneumatic dilatation or esophagomyotomy treatment for idiopathic achalasia: clinical outcomes and cost analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01296777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson CS, Fellows IW, Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Choice of therapy for achalasia in relation to age. Digestion. 1988;40:244–250. doi: 10.1159/000199661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Wilcox CM, Schroeder PL, Birgisson S, Slaughter RL, Koehler RE, Baker ME. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomised trial. Gut. 1999;44:231–239. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fellows IW, Ogilvie AL, Atkinson M. Pneumatic dilatation in achalasia. Gut. 1983;24:1020–1023. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.11.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng YS, Li MH, Chen WX, Chen NW, Zhuang QX, Shang KZ. Selection and evaluation of three interventional procedures for achalasia based on long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2370–2373. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]